Difference between revisions of "Paleolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

====Cave of El Castillo==== | ====Cave of El Castillo==== | ||

[[File:Cueva del Castillo.jpg|thumb|200 px|Access to the cave, in April 2008.]] | [[File:Cueva del Castillo.jpg|thumb|200 px|Access to the cave, in April 2008.]] | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[File:Cueva del Castillo interior.jpg|thumb|200px|Interior of the Cave of El Castillo]] |

The '''Cueva de El Castillo''', or the ''Cave of the Castle'', was discovered in 1903 by [[Hermilio Alcalde del Río]], the Spanish archaeologist, who was one of the pioneers in the study of the earliest cave paintings of Cantabria. The entrance to the cave was smaller in the past, but it has been enlarged as a result of archeological excavations. | The '''Cueva de El Castillo''', or the ''Cave of the Castle'', was discovered in 1903 by [[Hermilio Alcalde del Río]], the Spanish archaeologist, who was one of the pioneers in the study of the earliest cave paintings of Cantabria. The entrance to the cave was smaller in the past, but it has been enlarged as a result of archeological excavations. | ||

By way of this entrance one can access the different rooms in which Alcalde del Río found an extensive sequence of images. The paintings and other markings span from the [[Lower Paleolithic]] to the [[Bronze Age]], and even into the [[Middle Ages]]. There are over 150 figures already cataloged, including those that emphasize the engravings of a few deer, complete with shadowing. | By way of this entrance one can access the different rooms in which Alcalde del Río found an extensive sequence of images. The paintings and other markings span from the [[Lower Paleolithic]] to the [[Bronze Age]], and even into the [[Middle Ages]]. There are over 150 figures already cataloged, including those that emphasize the engravings of a few deer, complete with shadowing. | ||

| − | Among the artworks were found the oldest known [[Cave painting|cave art]] in the world. Hand stencils and disks made by blowing paint onto the wall were found to date back to at least 40,800 years, making them the oldest known cave art in Europe, 5,000-10,000 years older than previous examples from [[Chauvet | + | Among the artworks were found the oldest known [[Cave painting|cave art]] in the world. Hand stencils and disks made by blowing paint onto the wall were found to date back to at least 40,800 years, making them the oldest known cave art in Europe, 5,000-10,000 years older than previous examples from [[Chauvet Cave]] in France. <ref>Jean Clottes, ''Chauvet Cave: The Art of Earliest Times'' (University of Utah Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0874807585).</ref><ref>Jonathan Amos, [http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-18449711 Red dot becomes 'oldest cave art'] ''BBC News'', June 14, 2012. Retrieved October 10, 2013.</ref> |

As traditional methods such as radiocarbon dating do not work where there is no organic pigment, a team of British, Spanish, and Portuguese researchers led by Alistair Pike of the [[University of Bristol]] dated the formation of tiny stalactites on top of the paintings using the radioactive decay of [[uranium]]. This gave a minimum age for the art. Where larger stalagmites had been painted, maximum ages were also obtained. | As traditional methods such as radiocarbon dating do not work where there is no organic pigment, a team of British, Spanish, and Portuguese researchers led by Alistair Pike of the [[University of Bristol]] dated the formation of tiny stalactites on top of the paintings using the radioactive decay of [[uranium]]. This gave a minimum age for the art. Where larger stalagmites had been painted, maximum ages were also obtained. | ||

Revision as of 22:01, 10 October 2013

| Cave of Altamira and Paleolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | Spain |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii |

| Reference | 310 |

| Region** | Europe and North America |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1985 (9th Session) |

| Extensions | 2008 |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

Cave of Altamira and Paleolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain is the name under which are grouped 18 caves located in different regions of northern Spain, which together represent the apogee of Paleolithic cave art in Europe between 35,000 and 11,000 B.C.E. Altamira Cave was declared a World Heritage Site in 1985. In 2008 the site was expanded to include the 17 additional caves. These caves are located in three autonomous regions: Cantabria, Asturias, and the Basque Country.

Cave of Altamira

Chief among the caves in this World Heritage Site is Altamira, located within the town of Santillana del Mar in Cantabria. It remains one of the most important painting cycles of prehistory, originating in the Magdalenian and Solutrean periods of the Upper Paleolithic. This cave's artistic style represents the Franco-cantabrian school, characterized by the realism of its figural representation.

The cave is 270 meters long and consists of a series of twisting passages and chambers. Around 13,000 years ago a rockfall sealed the cave's entrance, preserving its contents until a nearby tree fell and disturbed the rocks, leading to its discovery by a local hunter, Modesto Peres, in 1868.

Excavations in the cave floor found deposits of Upper Solutrean (dated at approximately 18,500 years ago) and Lower Magdalenean (dated between 16,500 and 14,000 years ago) artifacts. Human habitation was limited to the cave mouth but artwork was discovered on the walls throughout the cave. Solutrean images include images of horses, goats, and hand prints created from the artists placing their hands on the cave wall and applying paint over it leaving a negative image of the palms. Art dated to the Magdelenean occupation also includes abstract shapes.

The cave itself is no longer open to the public, in an attempt to preserve the paintings which became damaged by the carbon dioxide in the damp breath of large numbers of visitors. A replica cave and museum were built nearby, effectively reproducing the cave and its art.

Cantabria

In addition to Altamira, the site includes nine additional caves located in Cantabria. These are Cave of Chufín; Cave of Hornos de la Peña; Cave of El Pendo; Cave of La Garma; Cave of Covalanas; and the Complex of the Caves del Monte Castillo in Puente Viesgo which includes the following chambers: Cave of Las Monedas, Cave of El Castillo, Cave of Las Chimeneas, and Cave of La Pasiega.

Cave of Chufín

The Cave of Chufín located in the town of Riclones in Cantabria (Spain). It is located in the place of confluence of the Lamasón and Nansa rivers in an environment with steep slopes where there are several caves with rock art. It is one of the caves included in the list of World Heritage of UNESCO since July 2008, within the site "Cave of Altamira and Paleolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain."

It were discovered by the photographer Manuel de Cos Borbolla, natural of Rabago (Cantabria)

In Chufín found different levels of occupation, the oldest being around 20000 years old. The cave, small size, has some deep sentillez subtle engravings and paintings from red deer, goats and cattle that are represented very schematically.

It also found a large number of symbols. One group, called type "sticks," accompanies the paintings inside animals. There is also a large number of drawings using points (puntillaje), including one which has been interpreted as a representation of a vulva.

Cave of Hornos de la Peña

The Cave of Hornos de la Peña is situated on a hill near the village of Tarriba in San Felices de Buelna. It was discovered in 1903. The most notable paintings are a headless bison, horse, and others at various levels in the first room and the second set of 35 figures are animals such as horses, bison, aurochs, goats, and other animals. The dating of the paintings indicate that they were created in the initial or middle Magdalenian period.

Cave of El Pendo

The Cave of El Pendo is situated in the heart of the Camargo Valley. The cave measures up to 40 meters (130 ft) in width and 22 meters (72 ft) in height, and dates from around 20,000 B.C.E. The ‘Frieze of Paintings,’ a panel measuring 25 meters (82 ft) in length is visible from any point in the main hall. This panel contains a number of figures painted in red, including several deer, a goat, a horse, and various other symbols, all drawn using the contour technique.

Cave of La Garma

The Cave of La Garma is located on La Gama Mountain. It is divided into various levels: the upper hall contains human burial sites; the intermediate level has a large number of palaeontological remains, mainly bones; the lower level consists of three, intact areas with many examples of painted art. They date from 28,000-13,000 years ago. The paintings include a realistic black horse, goats, bison, panels with hands, as well as many symbols painted in red.

Cave of Covalanas

The Cave of Covalanas was first discovered to have art work in 1903, though the cave was well known to the locals who knew it as "la cueva de las herramientas" (Tools Cave). It is situated on the South-Western hillside of Pando mountain, very close to the village of Ramales de la Victoria.

It has two galleries, one of which contains rock paintings. There are 22 red images: 18 are of deer, a stag, a horse, an aurochs, and a hybrid-type figure. There are also several symbols, small dots, and lines. The figures are distinctive for their technique, with a stippled outline made with the fingers. Given the limited use of this technique, a possible "Escuela de Ramales" (School of Ramales) has been postulated, establishing chronologically this kind of painting between 20,000 and 14,400 years ago.

Complex of the Caves del Monte Castillo

The Caves of Monte Castillo, located in the Cantabrian town of Puente Viesgo, contain one of the most important Paleolithic sites in the region. These include the caves Las Monedas, El Castillo, Las Chimeneas, and La Pasiega. This set of caves is located along the Pas river in the Castillo mountain, squarely at the intersection of three valleys and near the coast. This is a fertile ground for agriculture, hunting, and fishing, which explains the emergence of several prehistoric settlements there.

The caves contain decorations in red ochre in the forms of hand stencils (from as far back as 35 300 B.C.E.) and dots. One dot has been dated to 38 800 B.C.E., making it the oldest dated cave decoration in the world as of 2012.[1][2]

Cave of Las Monedas

The Cave of Las Monedas was named the Bear Cave on its discovery in 1952. Later, a collection of 20 coins from the days of the Catholic Monarchs were discovered in a sinkhole, leading to the renaming of the cave "Las Monedas" (coins). The cave is 800 meters (2,600 ft) in length, and contains stalactites, stalagmites, columns and colored karst formations. The paintings, which date from around 10,000 B.C.E., are located in a small side grotto. They include animal figures (horses, reindeer, goats, bison, and a bear) as well as groups of symbols.

Cave of Las Chimeneas

The Cave of Las Chimeneas (Cave of the Chimneys) was discovered in 1953. The chimneys are limestone shafts connecting the two levels of the cave. There are several panels of macaroni-type engravings, made with the fingers on clay. There are also black paintings, representations of animals and quadrangular symbols. Two of the figures (a deer and a symbol) are dated 13,940 and 15,070 B.C.E. respectively.

Cave of El Castillo

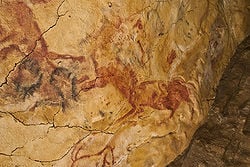

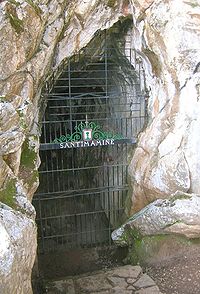

The Cueva de El Castillo, or the Cave of the Castle, was discovered in 1903 by Hermilio Alcalde del Río, the Spanish archaeologist, who was one of the pioneers in the study of the earliest cave paintings of Cantabria. The entrance to the cave was smaller in the past, but it has been enlarged as a result of archeological excavations.

By way of this entrance one can access the different rooms in which Alcalde del Río found an extensive sequence of images. The paintings and other markings span from the Lower Paleolithic to the Bronze Age, and even into the Middle Ages. There are over 150 figures already cataloged, including those that emphasize the engravings of a few deer, complete with shadowing.

Among the artworks were found the oldest known cave art in the world. Hand stencils and disks made by blowing paint onto the wall were found to date back to at least 40,800 years, making them the oldest known cave art in Europe, 5,000-10,000 years older than previous examples from Chauvet Cave in France. [3][4]

As traditional methods such as radiocarbon dating do not work where there is no organic pigment, a team of British, Spanish, and Portuguese researchers led by Alistair Pike of the University of Bristol dated the formation of tiny stalactites on top of the paintings using the radioactive decay of uranium. This gave a minimum age for the art. Where larger stalagmites had been painted, maximum ages were also obtained. Using this technique they found a hand print on 'The Panel of Hands' to date older than 37,300 years and nearby a red disc made by a very similar technique dates to older than 40,800 years:

The results demonstrate that the tradition of decorating caves extends back at least to the Early Aurignacian period, with minimum ages of 40.8 thousand years for a red disk, 37.3 thousand years for a hand stencil, and 35.6 thousand years for a claviform-like symbol. These minimum ages reveal either that cave art was a part of the cultural repertoire of the first anatomically modern humans in Europe or that perhaps Neanderthals also engaged in painting caves.[1]

Cave of La Pasiega

Cueva de La Pasiega, or Cave of La Pasiega, situated in the Spanish municipality of Puente Viesgo, is one of the most important monuments of Paleolithic art in Cantabria. It is included in the UNESCO schedule of Human Heritage since July 2008, under the citation "Cave of Altamira and palaeolithic cave art of Northern Spain."[5]

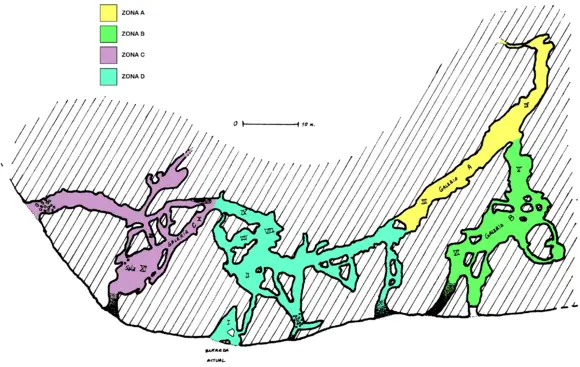

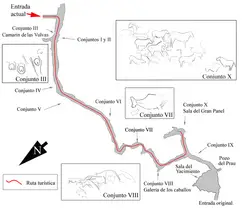

It is located in the heart of the uniprovincial community, in the middle of the valley of the river Pas, around the cave of Hornos de la Pena and Monte Castillo, in the same group of caves as Las Monedas, Las Chimeneas, and the cave of El Castillo. The caves of Monte Castillo form an amazingly complete series, both as regards the material culture of the Old Stone Age and from an artistic point of view. La Pasiega is basically an enormous gallery, its known extent more than 120 meters, that runs more or less parallel to the slope of the mount, opening to the surface at six different places: six small mouths, the majority obstructed, of which two can be accessed for inspection. The principal gallery is approximately 70 meters and opens to deeper secondary galleries, winding and labyrinthine, which in places broaden out to form large chambers. Thus one refers to "room II-VIII," the room called "Gallery B," or "room 11" of "Gallery C," all with paleolithic decorations. The two last mentioned rooms contain some of the rock sanctuaries that will be mentioned below.

The recorded remains belong mainly to the Upper Solutrean and the Lower Magdalenian ages, although older objects are also found. Throughout the cave are many 'walls' with paintings and with engraved or incised images. There are representations of equines (horses), cervids (deer, male and female) and bovines (cattle). There are also many abstract symbols (ideomorphs).

- The discovery of La Pasiega

The scientific discovery of the La Pasiega can be credited to Wernert and Hugo Obermaier. While excavating the cave of El Castillo in 1911, they received news that the workers knew of another cavity nearby that villagers called "La Pasiega." The investigators soon confirmed that the cave contained rock paintings. Later, Henri Breuil, Hugo Obermaier, and Hermilio Alcalde del Río began their systematic study of the cave. However, the study could not be finished due to Henri Breuil's ongoing work on his magnum opus.[6] A separate monograph was necessary, and was published in 1913.[7] Both publications were issued in Monaco because it was Prince Alberto I of Monaco who was patron of the investigations, ever since he had visited the site in 1909. It is no secret that this ruler was a great lover of archaeology, and not only did he support this excavation and others greatly, but also one of the fossil humans is named in his honour "Grimaldi Man," one of many names given to Homo sapiens fossilis): and the crowning example was his founding of the Institut de Palaeontologie Humaine in Paris.</ref> The study was crucial to the advancement of prehistoric science in Spain.

"In the next decade, Alcalde del Río was to assist fully in the international project that the Institut de paléontologie humaine in París sponsored, in which Abbé Breuil and H. Obermaier were prominent. That is the period in which the cave of La Pasiega was discovered. This is the most important moment in the study of Cantabrian rock art. The fruits of this labour were to feature in the monumental joint publications on the caves of the region, issued in Monaco, in the general work (Alcalde del Río, Breuil and Sierra, 1911), and specifically on La Pasiega (Breuil, Obermaier and Alcalde del Río, 1913)" —Joaquín González Echegaray[8]

Previously, the cave El Castillo was discovered by Alcalde del Río in 1903, and, as noted, Obermaier carried out excavations between 1910 and 1914. The excavations were continued at various times, intermittently, until our own times, by qualified specialists.[9] Ultimately the investigation was taken up by the archaeologists Rodrigo de Balbín Behrmann and César González Sainz. After the discovery of "La Pasiega" and the first campaigns, the area was little visited —mainly owing to the difficult historical circumstances of Spain in the 1930s. After this, in 1952, while a eucalyptus plantation was being put in, another cave was found with a small monetary treasure of the 17th century: hence the new cave was called "Las Monedas": in it, however, was found a rock sanctuary with important pictures and drawings. In light of this, the engineer Alfredo García Lorenzo concluded that Monte Castillo held more secrets. Therefore a geological survey was set in motion which resulted the following year in the discovery of another cave with rock paintings, "Las Chimeneas" ("The Chimneys"), and also other covachas of lesser importance such as "La Flecha," "Castañera," "Lago" etc.

- The other archeologists of La Pasiega

The cave, because it had remains of the primary Cantabrian Solutrean and Magdalenian epochs, provided the basis for a chronological series for the 'wall' paintings. The excavations were old, most recently conducted by Dr. Jesus Carballo in 1951. There was a base level with ambiguous artefacts which, by their characteristics, seemed related to a possible Mousterian phase. Above that there rested a comparatively rich Solutrean level with very characteristic implements such as 'feuilles de laurier' (leaf-points) and notched points with the finest working produced by light pressure-flaking, like light javelin points. This level could be attributed accurately to the Upper Solutrean. The most recent layer was also relatively rich, with various burins (borers), striker pins, and perforated objects of bone and that could belong to the Lower Magdalenian. Certainly, compared with the stratigraphical significance of El Castillo, La Pasiega is an archeological sequence of less organization, so far as the materials yet found are concerned However they should certainly not be less valued for this.

- The cave paintings of La Pasiega

On the plan proposed by André Leroi-Gourhan, La Pasiega can be taken as a good example of the "Cave as Sanctuary," or to be more precise as a collection of sanctuaries of different epochs, arranged according to certain models. In fact this idea developed in the thoughts of the distinguished French prehistorian precisely when he visited the Cantabrian caves, while he was participating in a group of foreign investigators who were excavating in the cave of El Pendo during the 1950s. "I can definitely confirm that the study of the rock art of northern Spain was decisive in the master's ideas, which since then have become famous through his many publications."[10] For Leroi-Gourhan, this type of cave has a rather complex spatial or topographical hierarchy in which it is possible to discern principal groups of animals (bos facing equus, forming a duality), which occupy the most conspicuous or preferred areas, complemented by secondary animals (deer, goat, etc) and other more occasional species which however fulfil their subsidiary function: on the other hand it is usual that the ideomorphic symbols appear in peripheral or marginal areas, or in those which are difficult to reach:[11]

Animals and symbols correspond, therefore, to the same basic formulae, logically binary and even defended by the fact that animals of the same species appear frequently in pairs, male and female, though the dispositivo is so complex that we ought not suppose an explanation purely based in the symbolism of fertility; the first element is the presence of two species A-B (horse-bison); confronted with two types of signs, masculine and feminine, an attempt to attribute to the horse and bison the same symbolic value or, at least, a bivalency of the same kind as that of the symbols of the two categories (S1 and S2)[12]

It is supposed that there are exceptions to this rule, many variants which depend on regions and epochs, the metaphyical significance of which is not entirely clear in its general outline, but which should be explained in a particular way, also at La Pasiega.

Joaquín González Echegaray[13] and later his fellow-workers[14] have made various counts of the species of animal represented, one of which reckoned more than 700 painted forms in this cave, among others: 97 deer (69 females and 28 males), 80 horses, 32 ibex, 31 cattle (17 bison and 14 aurochs), two reindeer, a carnivorous animal, a chamois, a megaloceros, a bird and a fish; also there may be a mammoth and about 40 quadrupeds not clearly identified; also the ideomorphs, such as roof-shaped and other surprisingly varied symbols (more than 130), and very often including various anthropomorphs and hundreds of marks and partly erased traces.

- Gallery A, 1st Sanctuary

To get into Gallery A it is necessary to descend by a little well, but originally one could go in by another entrance which, however, is now thoroughly blocked by stalactites and by collapses from outside. The gallery runs to a depth of 95 meters (from the present entrance), but it gets narrower and it is not possible to know whether it continues beyond. Entering into the cave, one passes a blocked entrance on the right, and between 60 and 70 meters depth appears the connection to Gallery B, slightly before the most interesting collection of pictures.

Then at a bit more than 75 meters it seems that the sanctuary (properly so-called) begins, with more than 50 deer (the majority female), the horses about half that number, and the cattle (aurochs and bison) fewer, strategically placed dominating the most visible places. In this sanctuary there have been found an anthropomorph, a vulva, linear and dotted symbols, a square and a great quantity of tectiforms, about as many as the deer.

The paintings can be put together in various groups, paying attention, above all, to dating criteria, but also technical and thematic sequence which unfolds like clockwork. These groups seem schematized with the semiotic zoological conventions unravelled by Leroi-Gourhan.

The First Large Group is on the left hand wall of the gallery, including figures arranged as a double frieze with numerous deer, mostly female, and also plenty of horses and a bison which is at the centre of the composition. Between them are symbols which stress the association of the vulva and the rod, the male-female distinction. The group brings out the theme of Bison-Horse which can also be interpreted as the same type of dualism. The group is completed by another little group of horses, the remaining animals being in the centre and the upper part of the frieze, where there are only hinds and ideomorphs.

File:La Pasiega-Galería A-1er Santuario-1er grupo.svg |

File:La Pasiega-Galería A-Primer grupo (oposición Bisonte-Caballos).png from the First Group, Gallery A |

The techniques of execution include outlines for hinds and bison, linear drawing (between outline and modelling) and, only in two places, partial tinta plana (selective infilling) is used (for the heads of certain hinds). The dominant colour, without any doubt, is red, but in a small way yellow and purplish red also appear. Engraving was not used in this group.

After this one finds a series of groupings of less organization, more or less connected with these, on the left wall of the gallery: in them appear every kind of figure that, certainly, complement the following group. They are clearly dominated by deer in association with some ideomorphs and a few cattle (possibly aurochs), which seem to stand in relation to the horses in the group which next appears round a corner.

The Second Large Group begins around a bend to the left, in the end area of the gallery, where it becomes narrow: it brings together figures on one side and the other. This time the horses and the deer are almost equal in number, as usual at La Pasiega, and fewer but not less important are the cattle, two of which are bison. Also there is a possible feminine anthopomorph and about thirty rectangular tectiform symbols, positioned in the way that seems to be usual in this type of cave sanctuary:

"The symbols, in general, occupy a separate space from the animals, either in the borders of the panels, or running into a niche or hollow, or a cranny more or less nearby. Even so, there are reasons to think that the signs are placed in relation to the same animals."[15]

The cattle are concentrated on the right side, together with three of the horses, forming the nucleus of the binary dialectic arrangement of this second group, and moreover, there is also included with them the anthropomorph, all surrounded by the typical peripheral animals (deer) and ideomorphs. On the left wall, together with more deer, the other five horses which apparently stand in binary relation to the cattle painted before the bend, which have been mentioned in the earlier description. At the end of the gallery, which is starting to turn into a narrow defile, there are rectangular signs on either side.

File:La Pasiega-Galería A-(Bisonte-Caballo).png The bison–horse confrontation (complemented by a tectiform sign, from the 'Second Group' of Gallery A |

File:La Pasiega-Galería A-1er Santuario-2o grupo.svg Grouping formula of the Second Group, Gallery A |

Nearby, in a little recess there is a third group of lesser extent. In this are five deer, an ibex and a bovid, all complemented by seven quadrangular signs, one of them shaped like the segment of an orange. The arrangement seems clear in principle: the pictures of the two walls form two confrontations, on one side the bovid with some deer and ideomorphic signs; this confronts the horses which, in this way, align themselves with the bison, and the rest of the deer, the signs, and the goat.

All this large complex of paintings is predominantly in modeled outline drawing in red.

The Third Large Group is sited on a stalagmite formation which hangs from the vault (such as has the speleological name bandera), between the first group already described and the last, which will be described below. The two groups, although they are near to one another, are executed in a different technique giving rise to the suspicion that they were created in different periods. There are about ten hinds, also several horses (though not so many), two cattle and a square symbol. Coming from the entrance direction, one sees first most of the hinds, followed by the association of the horses, below which are the symbol and the remaining hinds.

File:La Pasiega-Galeria A-Ciervas (panel 22).png Hinds painted in red in 'tinta plana', Third Group, Gallery A |

File:La Pasiega-Galería A-1er Santuario-3er grupo.svg Grouping formula, 3rd Group, Gallery A |

File:La Pasiega-Galería A-1er Santuario-4o grupo.svg Grouping formula, 4th Group, Gallery A |

The predominant technique, for its warmth and for its frequency of use, is the tinta plana - the plane or block colour – either combined with black lines forming an outline in a sort of two-colour method (as occurs on one of the horses), or emphasized with engraved lines which define details (this can be seen on various hinds), or enclosed, with scraffito in the rock to add chiaroscuro textures, as happens with a hind painted in red. Three of the horses and the head of another are black, the square sign is yellow, and the remainder of the figures are red.

The Fourth (and last) Large Group, placed facing the group just described, is in a very close relationship to it, containing a similar number of deer and horses, together with a pair of bison. Among the various symbols an ideomorph in the shape of a hand is prominent, reminiscent of those at Santián,[16] and a red sign which could well be meant for a grotesque bison head. In the central position appear a horse and a bison, forming the typical binary combination, at one end other bison and at the opposite end the remaining horses. There is no tinta plana, no engraving and no two-colour work: on the contrary, it is predominantly (more or less modeled) outline work in red.

- Gallery B, 2nd Sanctuary

Entering through Gallery A, after 60 or 70 meters, through a tunnel on the right, the first big room of Gallery B is met with. Fairly far away from the entrance which is used nowadays there are various old exits to the exterior which have become blocked with the passage of time. One of them has been made into an opening, but it is not known whether, in the epoch in which this area was decorated, any of these were usable, which would be a help in understanding the point of view which the prehistoric artists would have taken in conceptualizing the zonal arrangement and levels of the room's decoration.

The pictorial density of this room is less than in Gallery A, with which it is partly to be associated. Among its depictions there is a roughly equal number of deer and horses, with a lesser number of cattle, following the customary pattern of this cave. But it is outstanding for the originality of some of its other figures, including a fish, a large ibex and ideomorphs like rods, key-shapes and an unprecedented little group of symbols popularly known as "The Inscription."

- La Pasiega-Galería B-panel 53.svg

Panel 53

- La Pasiega-Galería B-panel 55.svg

Panels 54 and 55

- La Pasiega-Galería B-panel 57.svg

Panel 57

So far as it has been possible to observe, the arrangement of all these figures amounts to a careful scheme of introduction to the main panels of Gallery A, supposing that this might have been the main entrance. At the entry (from Gallery A) is a little engraved hind, and later, signs of the kind named alfa by Leroi-Gourhan (that is to say, masculine), which appear on both sides of the gallery. Following the constructed entrance, on the right appears a fish, followed by a large male deer (stag) together with a little hind (both in black). Immediately before reaching the centre of the large room there appear signs on both sides, but this time they are of the beta type (feminine), red in colour. The crowning feature of this sanctuary consists of three groups or panels which repeat the scheme of cattle-horse complemented by secondary animals or without them. There are three other panels in which only horses appear, several of them on the same stalagmite columns, others on the walls. In this nucleus a hand in positive depiction is emphasised, not mutilated, but with six fingers!: a grill-shaped symbol, some unidentified animal engraved in striated lines and the only male ibex of the room.

- La Pasiega-Galeria B-Gran Ciervo (panel 59).png

Deer painted in red,

panel 59 - La Pasiega-Galeria B-Numero 50.png

Engraved horse,

panel 50 - La Pasiega-Galeria B-Numero 51.png

Horse painted in black,

panel 51 - La Pasiega-Galeria B-Numero 47.png

Male ibex painted in black, panel 47

The techniques employed by the painters recall, partly, those of Gallery A (which is why they have come to be considered as related rooms): red painting, between modeled and outline, red block colouring (tinta plana), with some internal modeling achieved by scraffito to the underlying rock and by the addition of lines of the same colour but in more intense shades. The most important difference is the copious use of engraving, both simple and striated, applied specially to the horses.

- Gallery C (room XI), 3rd Sanctuary

Access to Gallery C is found, after entering the cave, by a way through to the left crossing Gallery D. Along there opens "Room XI" of Gallery C. This, in the same way as Gallery B, has direct communication with the outside, despite the fact that it is obstructed by rubble and rocks which have certainly been introduced. Once again, the perception of the arrangement of the pictures is changed for the observer by the problem of the blocked entrances, as we have noticed in the second Sanctuary.

Leroi-Gourhan differentiates two clear parts to this sanctuary, located in separate places within the same room, and with different themes, technique and chronology.[17] In addition there are two ibexes in the original monograph indicated at number 67, produced in partial block colour by a kind of modeling and black in colour, a method which is not found in any of the remaining figures of the room.

The First Large Group of Room XI is the one found mainly around the presumed original entrance, now blocked. It contains mainly hinds, some stags, various cattle and a pair of horses, and also there is a goat. There are other symbols difficult to identify, some seeming to be animals, others anthropomorphs, and there is a positive hand impression coloured black, dotted signs, rod signs, and other ideomorphs, among which stands out the so-called "Trampa" (a kind of column which encloses, behind a symbol, a bison and a hind (more will be said of this anon). The arrangement of this group seems to correspond to a threefold or ternary structure with variations: bos-equus-cervus with various signs or bos-equus-anthropomorph with signs. The truth is that the complexity of this panel is great, given the concentration of very varied figures.

- La Pasiega-Galeria C-Macho Cabrio.png

Male ibex painted in black with modeled lines in Gallery C

- La Pasiega-Galería C-paneles 74-75.svg

Scheme of the wall depictions in panel 74-75 of Gallery C

- La Pasiega-Galería C-panel 79.svg

Scheme of the wall depictions of panel 79 of Gallery C

Clearly the dominant technique is red outline drawing, but in one of the panels is also found, for some deer, striated engraving of very fine execution: also, there are various figures in black. In addition, there is two-colour work on one of the cattle, in which red block painting and black lines are combined, this time a repainting of different date. The presumed anthropomorph seems to contain up to three colours, not a very usual thing in palaeolithic art (red, black and yellow). There are some yellow figures.

The Second Large Group is around the access area to Zone D, that is, on the opposite side of the room. The species represented show predominantly horses, followed by cattle, and fewer but certainly present are deer and ibex (for which the symbols are complementary to the foregoing group). The symbols are of indeterminate number, and are of distinct kind, including key-shaped and feather-shaped ones, and also barred and dotted ones. The reduction in number of the deer does not happen in any other parts of the cave, where they are in the majority, whereas the proportion of horses is increased.

- La Pasiega-Galeria C-panel 86.svg

Scheme of the wall depictions of panel 86 of Gallery C

- La Pasiega-Galería C-Panel 86.png

Overlay of painting and engraving,

Gallery C - La Pasiega-Galeria C-panel 83.svg

Scheme of wall depictions of panel 81-83 of Gallery C

- La Pasiega-Galería C-numero 83.png

Bison in dark coloration from panel 83,

Gallery

Here the arrangement is also complex. All the ideomorphs are in the area nearest to the cave mouth, and the overlays show repaintings, maybe in distinct periods. There are three possible sub-groups of horses without cattle (only two of the compositions are the typical A-B which have been observed up to this point). However there are plenty of isolated figures, above all round the entrance to the room from Zone D.

The dominant techniques are engraving of multiple lines, as if striated, and black painting: the yellows, reds and ochres are fewer. However there is an example of the two-colour work, in one representation, although it is not very prominent. As we have seen, the technique is also distinct from that of the earlier group and confirms the separation of the two areas within the room.

- Zone D

This is an intermediate part of the cave, which is probably an extension of the sanctuary of Gallery C, like a 'grey area', with much fewer and more sporadic images among which there is little coherency, apart from a pair of small groups which continue to repeat the theme of the cattle and horse dualism.

- Differences between the sanctuaries

Taken together, one can see clear differences between the various 'sanctuaries'. That of Gallery A, which is the most substantial, has no engraved work apart from a few images in which it is combined with block colour painting; on the other hand, tamponado method is very important, combined with other techniques of painting basically in red; the ibex is very scarce, but the deer are almost double in number to the horses and five times more frequent than the cattle. There are lots of rectangular tectiform ideomorphs.

In Gallery B, which has fewer images, one notices the absence of tamponado, while engraving (simple or striated) gains importance. The deer here are fewer, except in the room which was found in the 1960s; and the ideomorphs are completely different, with the so-called 'inscription' outstanding for its uniqueness.

Gallery C has, so to say, two independent sanctuaries, both with striated engraving, but while the first present images which are mainly red, in the second they are mainly black; here the goats attain an importance not seen in the rest of the cave, and the ideomorphs are fairly unique, particularly those painted in red.

Although both Gallery A and Gallery C have dual-colour work, the methods are different in each case.

- The ideomorphs of La Pasiega

The ideomorphs – and possible anthropomorphs – of La Pasiega are listed and classified as:

- Dotted signs: These are the simplest symbols in the cave. Generally they appear in two forms, one of which has many dots, usually not associated with animals, but with other ideomorphs to which they are complementary. They are commonest in Galleries B and C, in the latter the groups of many dots seem related to deer, but the symbols are painted and the animals engraved, from which it is possible to deduce that they are of different periods.

- La Pasiega-Galeria A-panel 46.png

Large group of dots

- La Pasiega-Galeria A-panel 48.png

Small group of dots

- La Pasiega-Galeria A-panel 16.png

Horse head associated with two large groups of dots

- La Pasiega-Galeria A-panel 44.png

Horse head associated with a small group of dots

In the second type, the dots can appear much more loosely grouped. Then it is certainly possible to associate them with animals without too much uncertainty. The small groups of dots always appear once or twice in each room combined with cattle. But there are two very distinct cases in Gallery A in which horses have an aureole of dots, and these are confronted one to the other as at the entrance to the room mentioned. The dotted forms are most common during the Solutrean period.

- Linear signs: These are more varied and complex both in their morphology and in their associations (there are examples shaped like arrows, branches, feathers, simple lines called rods (bastoncillos), etc.). They are sometimes associated with hinds. For example, one of the foremost panels of gallery A has these kinds of ideomorphs associated with a vulva and a hind. In the second group of Gallery C there is a bison (panel 83) which may have a linear sign associated (it looks like a javelin, but that idea is very controversial), as well as some other symbol. At the side is a feather-shaped symbol grouped with other key-shaped (claviform) ones (discussed below) which were not identified in the original monograph (but became known through an article by Leroi-Gourhan[18]).

- La Pasiega-Galeria A-panel 37.png

Rods

- La Pasiega-Galeria B-panel 60.png

Bar and dot signs

- La Pasiega-Galeria C-panel 79.png

Arrow-shaped sign

- La Pasiega-Galeria C-panel 82.png

Feather-shaped sign

Finally there is a series of signs involving rods which appear in the entries to Galleries B and C. Breuil interpreted this type of sign in relation to the topographical changes within the sanctuary, which is possible: they could be marks which the initiates followed, or which warned them of possible dangers such as clefts.[19] Certainly the difficult areas of the cave when visited can be negotiated more easily thereby. For Leroi-Gourhan, they are male symbols in binary relation to the cave itself, which represents the female principle (discussed below).

- Claviform signs: The signs called 'claviform' (key-shaped) are fairly abundant, specially in gallery B and in Room XI, but are doubtful if not indeed non-existent in Gallery A. Those of Room XI are the most characteristic and may be associated with horses. One of these can be considered as what Leroi-Gourhan calls a 'coupled sign',[18] made by uniting in the same ideomorph a line or bar (masculine) with a key-shape (feminine). The typology and chronology of these signs is very ample.

- La Pasiega-Galeria B-panel 58.png

Claviform symbols

- La Pasiega-Galeria C-panel 81.png

Coupled claviforms

- La Pasiega-Galeria C-panel 74b.png

Triangular sign

- La Pasiega-Galeria C-panel 74a.png

Polygonal signs

- Polygonal signs are a varied group, a general category which includes rectangular, pentagonal and hexagonal signs. There is one in every room and, although they are few, one can draw comparisons with examples in other caves. for example there is a grill-shaped sign in Gallery B which can be compared with others in the cave of Aguas de Novales and of Marsoulas. In Gallery A there is a rectangular sign comparable to one which is found in one of the recesses at Lascaux. Lastly there is a sign formed by a pentagon and a hexagon side by side which, in the opinion of the specialist Pilar Casado, should be classified as a variant of the oval signs.[20]

- Tectiform signs: These are without any question the most abundant signs of this cave. They have a more or less rectangular shape, with and without additions, with and without internal divisions. Despite their frequency, these signs are absent from Gallery B. Breuil established a chronology and development through all of them; according to Leroi-Gourhan they belong to Style III and they have parallels in many caves of Spain and France, the nearest being the cave of El Castillo. At La Pasiega they are met with in the end area and the narrow defile of Gallery A, and in the first large group of Room XI.

- Unique signs:

- La Trampa: Mentioning this strange pictorial group in his description of Gallery C, Breuil was the first to appreciate that really it is the result of painting a symbol like a rectangular black tectiform sign, of very evolved type, superimposed upon two older red figures. Leroi-Gourhan accepted that it was the result of combining paintings of different dates, but did not think it should be thought of as a developed tectiform sign: but he thought that the repainting was intentional and concerned the effect of enclosing the animals (the hind-quarters of a bison and the fore-parts, the head and forelegs of a deer) within the ideomorph; he included it all within Style III and interpreted it as a mithogram resulting from the combination of three symbols of femininity. Jordá Cerdá and Casado López do not admit of a female symbology in 'La Trampa', which they relate, rather, to other representations of sealed enclosures which occur in Las Chimeneas and La Pileta.[21]

- The 'Inscription' of Gallery B is even more complex and unique than these signs; such that Breuil interpreted it as an authentic inscription which contained a coded message for initiates. Leroi-Gourhan goes to some lengths to explain that, being deconstructed, the figure is composed of feminine symbols. Jordá sees in it a typical sign in the form of a 'sack' related to the sealed enclosures mentioned before, and to serpentine forms which appear at the end of its Middle Cycle. Casado López finds parallels at Marsoulas and Font de Gaume.

- Human representations: This includes human images, more or less realistic, whether of a part or of the whole human anatomy. The foremost of the partial representations is the vulva: there can be identified three of oval, another rectangular and one triangular, very near 'La Trampa'. Also in this group are the hands which are painted in different ways in la Pasiega: one of these is schematic, which is called a maniform, related, as said above, to those of Santian. There is also a red hand in positive (with six fingers and in relation to a rectangular grill sign). Finally there is another positive hand, but in black, with continuing lines which may be meant to represent an arm. After this come the presumed complete human representations or anthropomorphs.

- The anthropomorphs can be counted as three (four if we count the lines which seem to complete the black hand already mentioned), and all of them are very debatable. The most doubtful of all is in Gallery A, which could be a female representation associated with fragmentary animals which are difficult to identify. Also debatable is another, that is executed in red tinta plana, with a globular form, located in Room XI. Very near is the one anthropomorph accepted as such by all investigators, namely a figure in varied colours: the body is outlined in red, with a large mouth; by contrast the skin is black, and there are added some horns, also black (in the opinion of the specialists these are re-paintings of different dates): lower down the figure has a linear ideomorph in yellow ochre which Breuil interpreted as a phallus. In relation to this human shape there are two external red symbols.

- La Pasiega-Galeria C-panel 74c.png

Vulva

- La Pasiega-Galeria A-panel 11.png

Hand-shaped symbol

- La Pasiega-Galeria B-panel 54.png

Hand impression and ideomorph

- La Pasiega-Galeria C-panel 77.png

Anthropomorph

- Attempts to establish chronology

The cave of La Pasiega offers many examples of overpaintings and repaintings which allow one to make an attempt at a relative chronology: on the other hand, the great variety of techniques and colours employed make one think of a fairly extensive chronological sequence. The authors of the monograph brought out in 1913 ended by establishing three chronological phases which span practically the whole development of palaeolithic art: two Aurignacian phases, a Solutrean and a peak of two-colour work (very rare in such paintings), which could be Magdalenian[22] Later Henri Breuil, one of the authors of the monograph, increased the decorative phases to eleven, within the same chronological framework.[23]

Later came the analysis of Leroi-Gourhan,[24] who proposed a chronology, rather general certainly, which broadly was in agreement with González Echegaray.[25] In both publications the decorations of the whole of Gallery A and the first sub-sanctuary of Room XI are placed at the very start of Style III; whereas the second sub-sanctuary of the same room should be placed within the earliest Style IV. Leroi-Gourhan argued from the basis of comparing the works of Gallery A with Lascaux, although recognising that that is more archaic, suggested that they were contemporaneous. Recently, as a result of being able to apply absolute systems of dating to the paintings, it has been demonstrated that the style-classification proposed by Leroi-Gourhan, and some relative dating of other investigators, is shaky.

Professor Jordá took on the task of revising the chronology of La Pasiega.[26] His last publications place the decoration of this cave in his "Middle Cycle: Solutrean-Magdalenian," accepting integrally the eleven phases of Breuil, but without allowing (or at least seriously doubting) that any part of the decoration could really be Aurignacian. In the Solutrean phase of the Middle Cycle he includes the figures painted in red, and those with fine lines or outlines; also some of the figures in the tampanado method. The engravings of this period would be, according to Jordá, rare and crude. A little later come the incomplete red horses, but in a lively and realistic style, some of the ideomorphs and the so-called inscription. During the second part of his Middle Cycle, he says, of the Cantabrian Lower Magdalenian, the archaizing engraved contours continue, but there also appears the multiple and striated line drawing in the horses of Galleries B and C, and in the hinds of Gallery C. The painted figures can be red, with tamponado, outline or modelled line. But more important are the tinta plana red paintings treated with modelled chiaroscuro, sometimes associated with graved or black lines which complete them: These are the ones which express dynamism most of all (twisting of the neck, movement of the legs, etc.). For some authors, these figures are the most evolved. The bi-chromes are rare, and in the majority of cases we are dealing with later corrections in a different colour to the original painting. Only a horse from gallery A, in the final group, could be considered an authentic bichrome, comparable to those of El Castillo. The most abundant ideomorphs are the quadrangular ones with internal divisions. Jordá maintains that, during the Middle Cycle, the anthropomorphs disappear, even though La Pasiega contains a few: according to the oldest authors four, and according to the most recent only one.

For their part, Professors González Echegaray and González Sáinz seem to share the general idea proposed by Leroi-Gourhan, in accepting that the works of La Pasiega belong to Styles III and IV.[27] In fact, pretty much all of Gallery A and the first assemblage of Gallery C (room XI) belongs to Style III, in which predominates the red painting with simple lines or lined tamponados, also including the block colours and the addition of engraving or the bi-chrome work as a complement to model the volumes. For its part Style IV is present above all in Gallery B and in the second group of Gallery C: this phase has mainly the black colour or drawn with a fine linear outlining, almost without modeling, but with an internal filling of scratches. The engraved forms are most abundant (simple linear marks, or repeated or striated lines, including scraffito).

Asturias

Five caves are located in Asturias, all situated in the Comarca de Oriente: Cave of Tito Bustillo in Ribadesella, Cave of Candamo in Candamu, Cave of La Covaciella in Cabrales, Cave of Llonín in Peñamellera Alta, and Cave del Pindal in Ribadedeva.

Cave of Tito Bustillo

The Cave of Tito Bustillo was formerly known as Pozu´l Ramu. It was renamed in 1968 after one of a group of young men, including Celestino Fernández Bustillo, rappelled down into the cave and discovered the artwork. He died in a mountain accident a few days later and the cave was renamed in his honor.

Prehistoric paintings cover a large portion of the Cave of Tito Bustillow, with many painted over earlier works. The dating of the art ranges between 22,000 and 10,000 B.C.E. There are two especially significant sections: the Chamber of Vulvas which contains paintings of female forms, and the Main Panel which consists of numerous animals. The drawings of the female body, however, are of especial interest as they make use of the natural relief of the rock to suggest the three-dimensional form of the body.

Cave of Candamo

The Cave of Candamo is around 60 meters (200 ft) long and was discovered in 1914. The paintings are from the Solutrean period, of the Upper Palaeolithic, some 18,000 years ago. The cave consists of several sections, beginning with the Entrance Gallery. The hall of the engravings contains the most important panel in the cavern: the wall of the engravings, a complex collection of figures including deer, horses, bison, goats, a chamois, and other animals which are difficult to identify. The techniques used are varied, mixing painting and engraving. The Camarín, at the end of this hall, contains a stalactite waterfall, on top of which is a panel of bovids, horses, a goat, and an incomplete image of a bull. These animal images, created by climbing the large calcite formations, ladders, or scaffolding, are visible from all points of the main central chamber in the interior of the cave.[28] This hall also contains the Talud Stalagmite, a mural with figures of horses which precedes access to the Batiscias gallery. In the Hall of the Red Signs, we can see signs in the form of dots, lines and other symbols which some interpret as feminine and masculine.

Cave of La Covaciella

The cave of La Covaciella is located in the area known as Las Estazadas in Cabrales (Asturias). It was discovered in 1994 completely by chance when several of the local inhabitants entered the grotto through an opening which had been made during road construction.

La Covaciella is formed by a gallery 40 meters (130 ft) long which opens out onto a great chamber. Its interior space was sealed when the original entrance was blocked due to natural causes. Although closed to the public, the prehistoric art in this cave can be enjoyed at the visitor centre in Casa Bárcena in the village of Carreña de Cabrales. The paintings date back more than 14,000 years.

Cave of Llonín

Also known as "La Concha de la Cueva," the Cave of Llonín is located in a narrow valley on the banks of the Cares River. The cave runs for 700 metres and contains around thirty prehistoric engravings and paintings. These include images of deer, reindeer horns, goats, snakes, and a bison.

Cueva del Pindal

Cueva del Pindal is located near the town of Pimiango in Asturias, near the border of Cantabria. The cave is 300 meters (980 ft) long and has numerous cave paintings, mostly on the right-hand wall. The cave paintings were discovered in 1908. They include several bison and horses, with a duo comprising a bison and a horse as the main motif. There are also other creatures represented, including a fish and a mammoth, as well as symbols, dots, and lines. Both red and black colors were used. Their estimated age is between 13,000 and 18,000 years.

Basque Country

Three caves are located in the Basque Country.

Cave of Altxerri

Located on the eastern slopes of Beobategaña Mountain, Altxerri Cave contains rock engravings and paintings from the Magdalenian period, dating between 13,000 and 12,000 B.C.E. The engravings are well preserved. The paintings, however, have deteriorated on account of the damp, leading to the cave being closed to the public.

Cave of Ekain

The Cave of Ekain was already known to the people in the village of Sastarrain in Guipscoa, when the cave art was discovered in June 1969. The accessible part of the cave was small, but to the right of the entrance some boulders had blocked a small opening. When these boulders were moved aside, a larger passage was revealed, that runs for 150 meters (490 ft) and contains numerous paintings and engravings.[29] There is a large panel full of paintings of horses. In addition to horses, there are also other animals such as bison, deer, and goats.

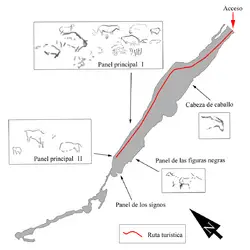

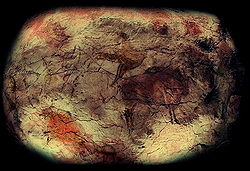

Cave of Santimamiñe

The Santimamiñe cave, is located in Kortezubi, Biscay, Basque Country on the right bank of the River Urdaibai and on the foothill of Ereñozar Mountain. The cave paintings were discovered in 1916 when some local boys explored them. It is best known for its mural paintings of the Magdalenian period, depicting bison, horses, goats, and deer.

It is one of the most important archaeological sites of the Basque Country, including a nearly complete sequence from the Middle Paleolithic to the Iron Age.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Alistair W.G. Pike et al., "U-Series Dating of Paleolithic Art in 11 Caves in Spain" Science, 336(6087) (June 15, 2012): 1409-1413. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ↑ Michael Marshall, "Oldest confirmed cave art is a single red dot" New Scientist (June 20, 2012): 10-11. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ↑ Jean Clottes, Chauvet Cave: The Art of Earliest Times (University of Utah Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0874807585).

- ↑ Jonathan Amos, Red dot becomes 'oldest cave art' BBC News, June 14, 2012. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ↑ Lamalfa, Carlos and Peñil, Javier, 'Las cuevas de Puente Viesgo', in Cuevas de España (Editorial Everest, León, 1991). ISBN 84-241-4688-3

- ↑ Breuil, H., Alcalde del Río, H., and Sierra, L., Les Cavernes de la Région Cantabrique (Espagne), Ed. A. Chêne. (Monaco 1911).

- ↑ Breuil, H., Obermaier, H., and Alcalde del Río, H., La Pasiega à Puente Viesgo, Ed. A. Chêne (Mónaco, 1913)

- ↑ González Echegaray, Joaquín (1994): 'Consideraciones preliminares sobre el arte rupestre cantábrico', in Complutum, Vol. 5, New Series of publications of the Complutense University of Madrid, pp 15-19. ISSN 1131-6993.

- ↑ Cabrera, V., Bernaldo de Quirós F. et al. (2004), 'Excavaciones en El Castillo: Veinte años de reflexiones', in Neandertales cantábricos, estado de la cuestión, vol. Actas de la Reunión Científica, Nº 20-22 (October) (Museo de Altamira, Ministerio de Cultura 2004).

- ↑ Gonzalez Echegaray 1994, 'Consideraciones preliminares sobre el arte rupestre cantábrico', in Complutum, Vol. 5, New Series of publications of the Complutense University of Madrid.

- ↑ Leroi-Gourhan, André, 'Consideraciones sobre la organización espacial de las figuras animales en el arte parietal paleolítico', in Símbolos, Artes y Creencias de la Prehistoria (Editorial Istmo, Madrid 1984). ISBN 84-7090-124-9

- ↑ Leroi-Gourhan, André, 'Los hombres prehistóricos y la Religión', in Símbolos, Artes y Creencias de la Prehistoria (Editorial Istmo, Madrid 1984). ISBN 84-7090-124-9

- ↑ González Echegaray, Joaquín, 'Cuevas con arte rupestre en la región Cantábrica,' in Curso de Arte rupestre paelolítico (Publicaciones de la UIMP, Santander-Zaragoza, 1978), pp 49-78.

- ↑ González Echegaray, Joaquín and González Sainz, César (1994), 'Conjuntos rupestres paleolíticos de la Cornisa Cantábrica', in Complutum, vol. 5, Nº Servicio de publicaciones de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, pp 21-43. ISSN 1131-6993.

- ↑ Leroi-Gourhan, 'Consideraciones sobre la organización espacial de las figuras animales en el arte parietal paleolítico', in Símbolos, Artes y Creencias de la Prehistoria (Editorial Istmo, Madrid 1984). ISBN 84-7090-124-9

- ↑ Jordá Cerdá, Francisco, 'Los estilos en el arte parietal magdaleniense cantábrico,' in Curso de Arte rupestre paleolítico, (Publicaciones de la UIMP [1], Santander-Zaragoza, 1978), p. 98.

- ↑ Leroi-Gourhan, André (1972): 'Considerations sur l'organisation spatiales des figures animales, dans l'art parietal paléolithique,' in las Actas del Symposium Internacional de Arte Prehistórico, vol. Santander, Nº pp. 281-308. This article is translated (into Spanish) as a chapter in: Leroi-Gourhan, André: 'Consideraciones sobre la organización espacial de las figuras animales en el arte parietal paleolítico', in Símbolos, Artes y Creencias de la Prehistoria (Editorial Istmo, Madrid, 1984). ISBN 84-7090-124-9

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Leroi-Gourhan, André (1958), 'La fonction des signes dans les sanctuaires paléolitiques,' in Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française, vol. 55, Nº Fascículos 7-8. ISSN 0249-7638

- ↑ Breuil, Henri (1952), Quatre cents siècles d'Art pariétal (New Edition by Max Fourny, París), pp. 373-374.

- ↑ Casado López, Pilar (1977), Los signos en el arte paleolítico de la península Ibérica, Monografías Arqueológicas (Saragossa), pp. 90 and 242.

- ↑ Jordá Cerdá, Francisco, 'Los estilos en el arte parietal magdaleniense cantábrico,' in Curso de Arte rupestre paleolítico, (Publicaciones de la UIMP, Santander-Zaragoza, 1978), p.73; Casado López, Pilar (1977), Los signos en el arte paleolítico de la península Ibérica, Monografías Arqueológicas (Saragossa), p.269.

- ↑ Breuil, H., Obermaier, H., and Alcalde Del Río, H., (1913), La Pasiega à Puente viesgo, Ed. A. Chêne (Mónaco).

- ↑ Breuil, Henri (1952), Quatre cents siècles d'Art pariétal, Re-ed. Max Fourny (París).

- ↑ Leroi-Gourhan, André (1968), Prehistoria del arte occidental, Editorial Gustavo Gili, (S.A, Barcelona). ISBN 84-252-0028-8.

- ↑ González Echegaray, Joaquín, 'Cuevas con arte rupestre en la región Cantábric', in Curso de Arte rupestre paelolítico (Publicaciones de la UIMP, Santander-Zaragoza, 1978).

- ↑ Jordá Cerdá, Francisco, 'Los estilos en el arte parietal magdaleniense cantábrico', en Curso de Arte rupestre paleolítico Publicaciones de la UIMP, Santander-Zaragoza, 1978.

- ↑ González Echegaray, Joaquín y González Sainz, César (1994), 'Conjuntos rupestres paleolíticos de la Cornisa Cantábrica,' in Complutum, vol. 5, Nº Servicio de publicaciones de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid. ISSN 1131-6993.

- ↑ César González Sainz and Roberto Cacho Toca, Peña de Candamo Cave, Asturias Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ↑ César González Sainz and Roberto Cacho Toca, Ekain Cave, Guipscoa, Basque Country Retrieved October 10, 2013.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bahn, Paul G. Cave Art: A Guide to the Decorated Ice Age Caves of Europe. Frances Lincoln, 2012. ISBN 978-0711232570

- Clottes, Jean. Chauvet Cave: The Art of Earliest Times. University of Utah Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0874807585

- Clottes, Jean. Cave Art. Phaidon Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0714857237

- Lawson, Andrew J. Painted Caves: Palaeolithic Rock Art in Western Europe. Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0199698226

External links

- Introduction to Cave Art in the Iberian Peninsula

- Prehistoric Caves of Cantabria

- Caves and Rock Shelters on the North coast of Spain

- El Chufín Cave

- Hornos de la Peña Cave

- El Pendo Cave

- La Garma Cave

- El Pindal Cave

- Tito Bustillo Cave

- Peña de Candamo Cavern

- Cueva de la Peña de Candamo

- Las Monedas Cave

- Cave of Las Chimeneas

- Virtual tour of the Covaciella cave

- Llonín Cave

- Altxerri Caves

- Ekain Cave

- Santimamiñe Cave

- Arte Paleolítico --- Cueva de La Pasiega

- Las cuevas de Monte Castillo

- Galería de fotos de las Salas A y B

- Galería de fotos de la Sala C

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Cave_of_Altamira_and_Paleolithic_Cave_Art_of_Northern_Spain history

- Cave_of_Chufín history

- Cave_of_El_Castillo history

- Cueva_de_La_Pasiega history

- Santimamiñe history

- Caves_of_Monte_Castillo history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.