Difference between revisions of "Neuron" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) m |

|||

| (34 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{Copyedited}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{2Copyedited}} |

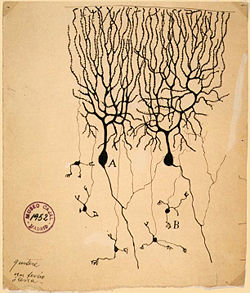

| − | [[Image:PurkinjeCell.jpg|thumb|250px| Drawing of neurons in the pigeon [[cerebellum]] by [[Santiago Ramón y Cajal]], the Spanish anatomist who first recognized the neuron’s role as the primary functional unit of the nervous system.]] | + | [[Image:PurkinjeCell.jpg|thumb|250px| Drawing of '''neurons''' in the pigeon [[cerebellum]] by [[Santiago Ramón y Cajal]], the Spanish anatomist who first recognized the neuron’s role as the primary functional unit of the nervous system.]] |

| + | '''Neurons''' (also known as '''neurones''' and '''nerve cells''') are electrically excitable [[cell (biology)|cells]] in the [[nervous system]] that process and transmit information from both internal and external environments. In [[vertebrate]] animals, neurons are the core components of the [[brain]], [[spinal cord]], and peripheral [[nerve]]s. Although the neuron is considered a discrete unit, the output of the nervous system is produced by the ''connectivity'' of neurons (that is, the strength and configuration of the connections between neurons). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The basic function of a neuron is to communicate information, which it does via chemical or electric impulses across a [[synapse]] (the junction between cells). The fundamental process that triggers these impulses is the [[action potential]], an electrical signal that is generated by utilizing the [[membrane potential|electrically excitable membrane]] of the neuron. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Neurons represent one component of a nervous system, which can be remarkably complex in higher organisms. Neurons allow an individual to continuously engage in a reciprocal relationship with its internal and external environment. The complex coordination exhibited by neurons in its interaction with other bodily cells and systems reveals the remarkable harmony in living organisms. | ||

| − | + | Neurons can be classified based on three broad roles: | |

| − | + | *[[Sensory neuron]]s have specialized receptors to convert diverse stimuli from the environment (such as light, touch, and pressure) into electric signals. These signals are then converted into chemical signals that are passed along to other cells. A sensory neuron transmits impulses from a ''receptor,'' such as those in the eye or ear, to a more central location in the nervous system, such as the spinal cord or brain. | |

| − | + | *[[Motor neuron]]s transmit impulses from a central area of the nervous system to an ''effector,'' such as a [[muscle]]. Motor neurons regulate the contraction of muscles; other neurons stimulate other types of cells, such as [[gland]]s. | |

| − | + | *[[Interneuron]]s convert chemical information back to electric signals. Also known as ''relay neurons,'' interneurons provide connections between sensory and motor neurons, as well as between each other. | |

| − | *Motor neurons regulate the contraction of muscles; other neurons stimulate other types of | + | {{toc}} |

| − | * | + | There is great heterogeneity across the nervous system and across species in the size, shape, and function of neurons. The number of neurons in a given organism also varies dramatically from species to species. The human brain contains approximately 100 billion (<math>10^{11}</math>) neurons and 100 trillion (<math>10^{14}</math>) [[synapse]]s (or connections between neurons). By contrast, in the nervous system of the [[roundworm]] ''Caenorhabditis elegans,'' males have 383 neurons, while hermaphrodites have a mere 302 neurons (Hobert 2005). Many properties of neurons, from the type of [[neurotransmitter]]s used to [[ion channel]] composition, are maintained across species; this interconnectedness of life allows scientists to study simple organisms in order to understand processes occurring in more complex organisms. |

| − | + | == The structure of a neuron == | |

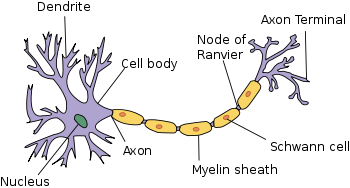

| + | [[Image:Neuron.svg|thumb|350px|The structure of a typical neuron includes four main components (from left to right): dendrites, cell body (or soma), axon, and axon terminal]] | ||

| + | Given the diversity of their functions, neurons have a wide variety of structures, sizes, and electrochemical properties. However, most neurons are composed of four main components: A [[Soma (biology)|soma]], or cell body, which contains the [[nucleus]]; one or more [[dendrite|dendritic tree]]s that typically receive input; an [[axon]] that carries an electric impulse; and an [[axon terminal]] that often functions to transmit signals to other cells. | ||

| − | The | + | *'''Soma.''' The cell body, or the soma, is the central part of the neuron. The soma contains the nucleus of the cell; therefore, it is the site where most of the [[protein]] synthesis in the neuron occurs. |

| − | The | + | *'''Axon.''' The axon is a finer, cable-like projection that can extend tens, hundreds, or even tens of thousands of times the diameter of the soma in length. The longest axon of a human motor neuron can be over a meter long, reaching from the base of the spine to the toes. Sensory neurons have axons that run from the toes to the dorsal column, over 1.5 meters in adults. [[Giraffe]]s have single axons several meters in length running along the entire length of the neck. Much of what is known about the function of axons comes from studying the axon of the [[giant squid]], an ideal experimental preparation because of its relatively immense size (several centimeters in length). |

| − | + | The axon is specialized for the conduction of a particular electric impulse, called the ''action potential,'' which travels away from the cell body and down the axon. Many neurons have only one axon, but this axon may—and usually will—undergo extensive branching, enabling communication with many target cells. The junction of the axon and the cell body is called the ''axon hillock.'' This is the area of the neuron that has the greatest density of voltage-dependent sodium channels, making it the most easily excited part of the neuron. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *'''Axon terminal.''' The axon terminal refers to the small branches of the axon that form the synapses, or connections with other cells. | |

| − | * | + | *'''Dendrites.''' The dendrites of a neuron are cellular extensions with many branches, where the majority of input to the neuron occurs. The overall shape and structure of a neuron's dendrites is called its ''dendritic tree.'' Most neurons have multiple dendrites, which extend outward from the soma and are specialized to receive chemical signals from the axon termini of other neurons. Dendrites convert these signals into small electric impulses and transmit them to the soma. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Although the canonical view of the neuron attributes consistent roles to its various components, dendrites and axons often act in ways contrary to their so-called main function. For example, while the axon and axon hillock are generally involved in information outflow, this region can also receive input from other neurons. Information outflow from dendrites to other neurons can also occur. | |

| − | + | Neurons can have great longevity (human neurons can continue to work optimally for the entire lifespan of over 100 years); with exceptions, are typically amitotic (and thus do not have the ability to divide and replace destroyed neurons); and normally have a high metabolic rate, requiring abundant carbohydrates and oxygen (Marieb and Hoehn 2010). | |

==The transmission of an impulse== | ==The transmission of an impulse== | ||

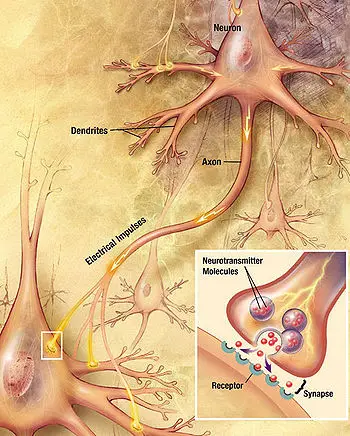

| − | [[ | + | [[File:Chemical synapse schema cropped.jpg|thumb|350px|Major elements in synaptic transmission. An electrochemical wave called an [[action potential]] travels along the [[axon]] of a [[neuron]]. When the wave reaches a [[synapse]], it provokes release of a small amount of [[neurotransmitter]] molecules, which bind to chemical receptor molecules located in the membrane of the target cell.]] |

| − | Neurons communicate with one another via [[synapse]]s, where | + | Neurons communicate with one another via [[synapse]]s, junctions where neurons pass signals to target cells, which may be other neurons, [[muscle]] cells, or [[gland]] cells. Neurons such as [[Purkinje cell]]s in the [[cerebellum]] may have over one thousand dendritic branches, making connections with tens of thousands of other cells; other neurons, such as the [[magnocellular neuron]]s of the [[supraoptic nucleus]], possess only one or two dendrites, each of which receives thousands of synapses. |

| − | Synapses | + | Synapses generally conduct signals in one direction. They can be [[EPSP|excitatory]] or [[IPSP|inhibitory]]; that is, they will either increase or decrease activity in the target neuron. |

===Chemical synapses=== | ===Chemical synapses=== | ||

| − | In a chemical synapse, the process of | + | '''Chemical synapses''' are specialized junctions through which the cells of the [[nervous system]] signal to each other and to non-neuronal cells such as those in [[muscle]]s or [[gland]]s. Chemical synapses allow the neurons of the [[central nervous system]] to form interconnected neural circuits. They thus are crucial to the biological computations that underlie perception and thought. They provide the means through which the nervous system connects to and regulates the other systems of the body. |

| + | |||

| + | In a chemical synapse, the process of signal transmission is as follows: | ||

| + | #When an action potential reaches the axon terminal, it opens voltage-gated calcium channels, allowing [[calcium]] ions to enter the terminal. | ||

| + | #Calcium causes vesicles filled with [[neurotransmitter]] molecules to fuse with the membrane, releasing their contents into the ''synaptic cleft,'' a narrow space between cells. | ||

| + | #The neurotransmitters diffuse across the synaptic cleft and activate receptors on the ''postsynaptic'' neuron (that is, the neuron receiving the signal). | ||

===Electric synapses=== | ===Electric synapses=== | ||

| − | + | While most neurons rely on chemical synapses, some neurons also communicate via electrical synapses. An '''electrical synapse''' is a mechanically and electrically conductive link that is formed at a narrow gap between two abutting neurons, which is known as a ''gap junction''. In contrast to chemical synapses, the postsynaptic potential in electrical synapses is not caused by the opening of ion channels by chemical transmitters, but by direct electrical coupling of the neurons. Electrical synapses are therefore faster and more reliable than chemical synapses. | |

| − | + | Many [[cold-blooded]] [[fish]]es contain a large number of electrical synapses, which suggests that they may be an adaptation to low temperatures: the lowered rate of [[metabolism|cellular metabolism]] in the cold reduces the rate of impulse transmission across chemical synapses. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

===The action potential=== | ===The action potential=== | ||

| − | + | The '''action potential''' refers to a series of sudden changes in the electric potential across the plasma membrane of a neuron. Generating the action potential is an all-or-nothing endeavor: each neuron averages all the electric disturbances on its membrane and decides whether or not to trigger an action potential and conduct it down the axon. The composite signal must reach a ''threshold potential,'' a certain [[voltage]] at which the membrane at the axon hillock is ''[[polarization|depolarized]]''. The frequency with which action potentials are generated in a particular neuron is the crucial factor determining its ability to signal other cells. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The narrow cross-section of the axon lessens the metabolic expense of carrying action potentials, but thicker axons convey impulses more rapidly. To minimize metabolic expense while maintaining rapid conduction, many neurons have insulating sheaths of [[myelin]] around their axons. The sheaths are formed by [[glial]] cells, which fill the spaces between neurons. The myelin sheath enables action potentials to travel faster than in unmyelinated axons of the same diameter, while using less energy. | |

| − | + | [[Multiple sclerosis]] is a neurological disorder that is characterized by patchy loss of myelin in areas of the brain and spinal cord. Neurons with demyelinated axons do not conduct electrical signals properly. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Some neurons do not rely on action potentials; instead, they generate a graded electrical signal, which in turn causes graded neurotransmitter release. Such ''nonspiking neurons'' tend to be sensory neurons or interneurons, because they cannot carry signals across long distances. | |

| − | |||

| − | The ' | + | ==The neuron doctrine== |

| + | The neuron's role as the primary functional unit of the [[nervous system]] was first recognized in the early twentieth century through the work of the Spanish anatomist [[Santiago Ramón y Cajal]]. To observe the structure of individual neurons, Cajal used a histological staining technique developed by his contemporary (and rival) [[Camillo Golgi]]. Golgi found that by treating [[brain]] tissue with a silver chromate solution, a relatively small number of neurons in the brain were darkly stained. This allowed Golgi to resolve in detail the structure of individual neurons and led him to conclude that nervous tissue was a continuous reticulum (or web) of interconnected [[cell (biology)|cell]]s, much like those in the [[circulatory system]]. | ||

| − | + | Using [[Golgi's method]], Ramón y Cajal reached a very different conclusion. He postulated that the nervous system is made up of billions of separate neurons and that these cells are [[polarization|polarized]]. Cajal proposed that neurons were discrete cells that communicated with each other via specialized junctions, or spaces between cells. This hypothesis became known as the ''neuron doctrine,'' which, in its longer form, holds that (Sabbatini 2003): | |

| + | *Neurons are discrete cells | ||

| + | *Neurons are genetically and metabolically distinct units | ||

| + | *Neurons comprise discrete components | ||

| + | *Neural transmission goes in only one direction, from dendrites toward axons | ||

| − | + | [[Electron microscope|Electron microscopy]] later showed that a [[cell membrane|plasma membrane]] completely enclosed each neuron, supporting Cajal's theory and weakening Golgi's reticular theory. However, with the discovery of electrical synapses, some have argued that Golgi was at least partially correct. For this work, Ramón y Cajal and Golgi shared the [[Nobel Prize#Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine|Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine]] in 1906. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | While the neuron doctrine has become a central tenet of modern [[neuroscience]], recent studies challenging this view have suggested that the narrow confines of the doctrine need to be expanded: | |

| + | *Among the most serious challenges to the neuron doctrine is the fact that electrical synapses are more common in the [[central nervous system]] than previously thought. Thus, rather than functioning as individual units, in some parts of the brain, large ensembles of neurons may be active simultaneously to process neural information (Connors and Long 2004). | ||

| + | *A second challenge comes from the fact that dendrites, like axons, also have [[voltage gated ion channel]]s and can generate electrical potentials that convey information to and from the soma. This challenges the view that dendrites are simply passive recipients of information and axons the sole transmitters. It also suggests that the neuron is not simply active as a single element, but that complex computations can occur within a single neuron (Djurisic et al. 2004). | ||

| + | *Finally, the role of [[glia]] in processing neural information has begun to be appreciated. Neurons and glia make up the two chief cell types of the central nervous system. There are far more [[glial cell]]s than neurons: Glia outnumber neurons by as many as ten to one. Recent experimental results have suggested that glia play a vital role in information processing (Witcher et al. 2007). | ||

==Classes of neurons== | ==Classes of neurons== | ||

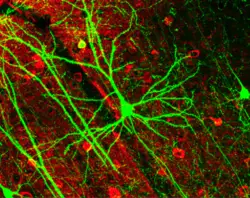

| − | [[Image:GFPneuron.png|thumb|250px|right| | + | [[Image:GFPneuron.png|thumb|250px|right|An image of ''pyramidal'' neurons in the mouse [[cerebral cortex]] expressing [[green fluorescent protein]]. The red staining indicates [[GABA|GABAergic]] interneurons. Source: PLoS Biology.<ref>Wei-Chung Allen Lee, Hayden Huang, Guoping Feng, Joshua R. Sanes, Emery N. Brown, Peter T. So, and Elly Nedivi, [http://biology.plosjournals.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.0040029 Dynamic Remodeling of Dendritic Arbors in GABAergic Interneurons of Adult Visual Cortex,] ''PLoS Biology.'' Retrieved August 28, 2007.</ref>]] |

| − | |||

===Structural classification=== | ===Structural classification=== | ||

Most neurons can be anatomically characterized as: | Most neurons can be anatomically characterized as: | ||

| − | *Unipolar or [[Pseudounipolar cells|Pseudounipolar]]: dendrite and axon | + | *Unipolar or [[Pseudounipolar cells|Pseudounipolar]]: The dendrite and axon emerge from the same process |

| − | *[[Bipolar cell|Bipolar]]: single axon and single dendrite on opposite ends of the soma | + | *[[Bipolar cell|Bipolar]]: The cell has a single axon and a single dendrite on opposite ends of the soma |

| − | *[[Multipolar neuron|Multipolar]]: more than two dendrites | + | *[[Multipolar neuron|Multipolar]]: The cell contains more than two dendrites |

| − | **[[pyramidal cell|Golgi I]]: | + | **[[pyramidal cell|Golgi I]]: Neurons with long-projecting axonal processes |

| − | **[[granule cell|Golgi II]]: | + | **[[granule cell|Golgi II]]: Neurons whose axonal process projects locally |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Some unique neuronal types can be identified according to their location in the nervous system and their distinct shape. Examples include basket, [[Betz cell|Betz]], [[Medium spiny neuron|medium spiny]], [[Purkinje cell|Purkinje]], [[pyramidal cell|pyramidal]], and [[Renshaw cell|Renshaw]] cells. | |

| + | ===Functional classifications=== | ||

| + | '''Classification by connectivity''' | ||

*[[Afferent neuron]]s convey information from tissues and organs into the central nervous system. | *[[Afferent neuron]]s convey information from tissues and organs into the central nervous system. | ||

| − | *[[Efferent neuron]]s transmit signals from the central nervous system to the [[effector cell]]s and are sometimes called motor neurons. | + | *[[Efferent neuron]]s transmit signals from the central nervous system to the [[effector cell]]s and are sometimes called ''motor neurons''. |

*[[Interneuron]]s connect neurons within specific regions of the central nervous system. | *[[Interneuron]]s connect neurons within specific regions of the central nervous system. | ||

| − | '' | + | The terms ''afferent'' and ''efferent'' can also refer to neurons which convey information from one region of the brain to another. |

'''Classification by action on other neurons''' | '''Classification by action on other neurons''' | ||

| − | * | + | *''Excitatory neurons'' evoke [[EPSP|excitation]] of their target neurons. Excitatory neurons in the brain are often [[glutamate|glutamatergic]]. [[Spinal cord|Spinal]] motor neurons use [[acetylcholine]] as their neurotransmitter. |

| − | * | + | *''Inhibitory neurons'' evoke [[IPSP|inhibition]] of their target neurons. Inhibitory neurons are often interneurons. The output of some brain structures (for example, neostriatum, globus pallidus, cerebellum) are inhibitory. The primary inhibitory neurotransmitters are [[GABA]] and [[glycine]]. |

| − | * | + | *''Modulatory neurons'' evoke more complex effects termed [[neuromodulation]]. These neurons use such neurotransmitters as [[dopamine]], [[acetylcholine]], [[serotonin]], and others. |

| − | '''Classification by discharge patterns'''<br> | + | '''Classification by discharge patterns'''<br/> |

Neurons can be classified according to their [[electrophysiology|electrophysiological]] characteristics: | Neurons can be classified according to their [[electrophysiology|electrophysiological]] characteristics: | ||

| − | * | + | *''Tonic or regular spiking'': some neurons are typically constantly (or tonically) active |

| − | * | + | *''Phasic or bursting:'' Neurons that fire in bursts |

| − | * | + | *''Fast spiking:'' Some neurons are notable for their fast firing rates |

| − | * | + | *''Thin-spike:'' Action potentials of some neurons are narrower than others |

'''Classification by neurotransmitter released''' | '''Classification by neurotransmitter released''' | ||

| − | + | Examples include cholinergic, GABA-ergic, glutamatergic, and dopaminergic neurons. | |

| + | |||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | <references/> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | * Bullock, T. H., M. V. L. Bennett, D. Johnston, R. Josephson, E. Marder, and R. D. Fields. 2005. “The Neuron Doctrine, Redux.” ''Science'' 310: 791-793. | |

| − | + | * Connors, B., and M. Long. 2004. “Electrical synapses in the mammalian brain.” ''Annu Rev Neurosci'' 27: 393-418. PMID 15217338. | |

| − | + | * Djurisic, M., S. Antic, W. Chen, and D. Zecevic. 2004. “Voltage imaging from dendrites of mitral cells: EPSP attenuation and spike trigger zones.” ''J Neurosci'' 24(30): 6703-6714. PMID 15282273. | |

| − | + | * Kandel, E. R., J. H. Schwartz, and T. M. Jessell. 2000. ''Principles of Neural Science,'' 4th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0838577016. | |

| − | * Bullock, T.H. | + | * Lodish, H., D. Baltimore, A. Berk, S. L. Zipursky, P. Matsudaira, and J. Darnell. 1995. ''Molecular Cell Biology,'' 3rd edition. New York: Scientific American Books. ISBN 0716723808. |

| − | * Kandel E.R. | + | * Marieb, E. N. and K. Hoehn. 2010. ''Human Anatomy & Physiology'', 8th edition. Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 9780805395693. |

| − | * Lodish, H. | + | * Peters, A., S. L. Palay, and H. D. Webster. 1991. ''The Fine Structure of the Nervous System: Neurons and Their Supporting Cells,'' 3rd edition. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195065719. |

| − | * Peters, A. | + | * Ramón y Cajal, S. 1933. ''Histology,'' 10th edition. Baltimore, MD: Wood. |

| − | * Ramón y Cajal, S. 1933 ''Histology'' | + | * Roberts, A., and B. M. H. Bush. 1981. ''Neurones Without Impulses: Their Significance for Vertebrate and Invertebrate Nervous Systems''. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052123364X. |

| − | * Roberts A., | + | * Sabbatini, R. M. E. 2003. [http://www.cerebromente.org.br/n17/history/neurons3_i.htm “Neurons and synapses: The history of its discovery.”] ''Brain & Mind Magazine'' 17. Retrieved August 28, 2007. |

| − | + | * Witcher, M., S. Kirov, and K. Harris. 2007. “Plasticity of perisynaptic astroglia during synaptogenesis in the mature rat hippocampus.” ''Glia'' 55(1): 13-23. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * [http:// | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{credit|101396606}} | + | {{credit|Neuron|101396606|Neuron_doctrine|132222201|Santiago_Ramon_y_Cajal|134336964}} |

[[Category:Life sciences]] | [[Category:Life sciences]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Anatomy and physiology]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Cell biology]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:15, 29 December 2014

Neurons (also known as neurones and nerve cells) are electrically excitable cells in the nervous system that process and transmit information from both internal and external environments. In vertebrate animals, neurons are the core components of the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves. Although the neuron is considered a discrete unit, the output of the nervous system is produced by the connectivity of neurons (that is, the strength and configuration of the connections between neurons).

The basic function of a neuron is to communicate information, which it does via chemical or electric impulses across a synapse (the junction between cells). The fundamental process that triggers these impulses is the action potential, an electrical signal that is generated by utilizing the electrically excitable membrane of the neuron.

Neurons represent one component of a nervous system, which can be remarkably complex in higher organisms. Neurons allow an individual to continuously engage in a reciprocal relationship with its internal and external environment. The complex coordination exhibited by neurons in its interaction with other bodily cells and systems reveals the remarkable harmony in living organisms.

Neurons can be classified based on three broad roles:

- Sensory neurons have specialized receptors to convert diverse stimuli from the environment (such as light, touch, and pressure) into electric signals. These signals are then converted into chemical signals that are passed along to other cells. A sensory neuron transmits impulses from a receptor, such as those in the eye or ear, to a more central location in the nervous system, such as the spinal cord or brain.

- Motor neurons transmit impulses from a central area of the nervous system to an effector, such as a muscle. Motor neurons regulate the contraction of muscles; other neurons stimulate other types of cells, such as glands.

- Interneurons convert chemical information back to electric signals. Also known as relay neurons, interneurons provide connections between sensory and motor neurons, as well as between each other.

There is great heterogeneity across the nervous system and across species in the size, shape, and function of neurons. The number of neurons in a given organism also varies dramatically from species to species. The human brain contains approximately 100 billion () neurons and 100 trillion () synapses (or connections between neurons). By contrast, in the nervous system of the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans, males have 383 neurons, while hermaphrodites have a mere 302 neurons (Hobert 2005). Many properties of neurons, from the type of neurotransmitters used to ion channel composition, are maintained across species; this interconnectedness of life allows scientists to study simple organisms in order to understand processes occurring in more complex organisms.

The structure of a neuron

Given the diversity of their functions, neurons have a wide variety of structures, sizes, and electrochemical properties. However, most neurons are composed of four main components: A soma, or cell body, which contains the nucleus; one or more dendritic trees that typically receive input; an axon that carries an electric impulse; and an axon terminal that often functions to transmit signals to other cells.

- Soma. The cell body, or the soma, is the central part of the neuron. The soma contains the nucleus of the cell; therefore, it is the site where most of the protein synthesis in the neuron occurs.

- Axon. The axon is a finer, cable-like projection that can extend tens, hundreds, or even tens of thousands of times the diameter of the soma in length. The longest axon of a human motor neuron can be over a meter long, reaching from the base of the spine to the toes. Sensory neurons have axons that run from the toes to the dorsal column, over 1.5 meters in adults. Giraffes have single axons several meters in length running along the entire length of the neck. Much of what is known about the function of axons comes from studying the axon of the giant squid, an ideal experimental preparation because of its relatively immense size (several centimeters in length).

The axon is specialized for the conduction of a particular electric impulse, called the action potential, which travels away from the cell body and down the axon. Many neurons have only one axon, but this axon may—and usually will—undergo extensive branching, enabling communication with many target cells. The junction of the axon and the cell body is called the axon hillock. This is the area of the neuron that has the greatest density of voltage-dependent sodium channels, making it the most easily excited part of the neuron.

- Axon terminal. The axon terminal refers to the small branches of the axon that form the synapses, or connections with other cells.

- Dendrites. The dendrites of a neuron are cellular extensions with many branches, where the majority of input to the neuron occurs. The overall shape and structure of a neuron's dendrites is called its dendritic tree. Most neurons have multiple dendrites, which extend outward from the soma and are specialized to receive chemical signals from the axon termini of other neurons. Dendrites convert these signals into small electric impulses and transmit them to the soma.

Although the canonical view of the neuron attributes consistent roles to its various components, dendrites and axons often act in ways contrary to their so-called main function. For example, while the axon and axon hillock are generally involved in information outflow, this region can also receive input from other neurons. Information outflow from dendrites to other neurons can also occur.

Neurons can have great longevity (human neurons can continue to work optimally for the entire lifespan of over 100 years); with exceptions, are typically amitotic (and thus do not have the ability to divide and replace destroyed neurons); and normally have a high metabolic rate, requiring abundant carbohydrates and oxygen (Marieb and Hoehn 2010).

The transmission of an impulse

Neurons communicate with one another via synapses, junctions where neurons pass signals to target cells, which may be other neurons, muscle cells, or gland cells. Neurons such as Purkinje cells in the cerebellum may have over one thousand dendritic branches, making connections with tens of thousands of other cells; other neurons, such as the magnocellular neurons of the supraoptic nucleus, possess only one or two dendrites, each of which receives thousands of synapses.

Synapses generally conduct signals in one direction. They can be excitatory or inhibitory; that is, they will either increase or decrease activity in the target neuron.

Chemical synapses

Chemical synapses are specialized junctions through which the cells of the nervous system signal to each other and to non-neuronal cells such as those in muscles or glands. Chemical synapses allow the neurons of the central nervous system to form interconnected neural circuits. They thus are crucial to the biological computations that underlie perception and thought. They provide the means through which the nervous system connects to and regulates the other systems of the body.

In a chemical synapse, the process of signal transmission is as follows:

- When an action potential reaches the axon terminal, it opens voltage-gated calcium channels, allowing calcium ions to enter the terminal.

- Calcium causes vesicles filled with neurotransmitter molecules to fuse with the membrane, releasing their contents into the synaptic cleft, a narrow space between cells.

- The neurotransmitters diffuse across the synaptic cleft and activate receptors on the postsynaptic neuron (that is, the neuron receiving the signal).

Electric synapses

While most neurons rely on chemical synapses, some neurons also communicate via electrical synapses. An electrical synapse is a mechanically and electrically conductive link that is formed at a narrow gap between two abutting neurons, which is known as a gap junction. In contrast to chemical synapses, the postsynaptic potential in electrical synapses is not caused by the opening of ion channels by chemical transmitters, but by direct electrical coupling of the neurons. Electrical synapses are therefore faster and more reliable than chemical synapses.

Many cold-blooded fishes contain a large number of electrical synapses, which suggests that they may be an adaptation to low temperatures: the lowered rate of cellular metabolism in the cold reduces the rate of impulse transmission across chemical synapses.

The action potential

The action potential refers to a series of sudden changes in the electric potential across the plasma membrane of a neuron. Generating the action potential is an all-or-nothing endeavor: each neuron averages all the electric disturbances on its membrane and decides whether or not to trigger an action potential and conduct it down the axon. The composite signal must reach a threshold potential, a certain voltage at which the membrane at the axon hillock is depolarized. The frequency with which action potentials are generated in a particular neuron is the crucial factor determining its ability to signal other cells.

The narrow cross-section of the axon lessens the metabolic expense of carrying action potentials, but thicker axons convey impulses more rapidly. To minimize metabolic expense while maintaining rapid conduction, many neurons have insulating sheaths of myelin around their axons. The sheaths are formed by glial cells, which fill the spaces between neurons. The myelin sheath enables action potentials to travel faster than in unmyelinated axons of the same diameter, while using less energy.

Multiple sclerosis is a neurological disorder that is characterized by patchy loss of myelin in areas of the brain and spinal cord. Neurons with demyelinated axons do not conduct electrical signals properly.

Some neurons do not rely on action potentials; instead, they generate a graded electrical signal, which in turn causes graded neurotransmitter release. Such nonspiking neurons tend to be sensory neurons or interneurons, because they cannot carry signals across long distances.

The neuron doctrine

The neuron's role as the primary functional unit of the nervous system was first recognized in the early twentieth century through the work of the Spanish anatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal. To observe the structure of individual neurons, Cajal used a histological staining technique developed by his contemporary (and rival) Camillo Golgi. Golgi found that by treating brain tissue with a silver chromate solution, a relatively small number of neurons in the brain were darkly stained. This allowed Golgi to resolve in detail the structure of individual neurons and led him to conclude that nervous tissue was a continuous reticulum (or web) of interconnected cells, much like those in the circulatory system.

Using Golgi's method, Ramón y Cajal reached a very different conclusion. He postulated that the nervous system is made up of billions of separate neurons and that these cells are polarized. Cajal proposed that neurons were discrete cells that communicated with each other via specialized junctions, or spaces between cells. This hypothesis became known as the neuron doctrine, which, in its longer form, holds that (Sabbatini 2003):

- Neurons are discrete cells

- Neurons are genetically and metabolically distinct units

- Neurons comprise discrete components

- Neural transmission goes in only one direction, from dendrites toward axons

Electron microscopy later showed that a plasma membrane completely enclosed each neuron, supporting Cajal's theory and weakening Golgi's reticular theory. However, with the discovery of electrical synapses, some have argued that Golgi was at least partially correct. For this work, Ramón y Cajal and Golgi shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1906.

While the neuron doctrine has become a central tenet of modern neuroscience, recent studies challenging this view have suggested that the narrow confines of the doctrine need to be expanded:

- Among the most serious challenges to the neuron doctrine is the fact that electrical synapses are more common in the central nervous system than previously thought. Thus, rather than functioning as individual units, in some parts of the brain, large ensembles of neurons may be active simultaneously to process neural information (Connors and Long 2004).

- A second challenge comes from the fact that dendrites, like axons, also have voltage gated ion channels and can generate electrical potentials that convey information to and from the soma. This challenges the view that dendrites are simply passive recipients of information and axons the sole transmitters. It also suggests that the neuron is not simply active as a single element, but that complex computations can occur within a single neuron (Djurisic et al. 2004).

- Finally, the role of glia in processing neural information has begun to be appreciated. Neurons and glia make up the two chief cell types of the central nervous system. There are far more glial cells than neurons: Glia outnumber neurons by as many as ten to one. Recent experimental results have suggested that glia play a vital role in information processing (Witcher et al. 2007).

Classes of neurons

Structural classification

Most neurons can be anatomically characterized as:

- Unipolar or Pseudounipolar: The dendrite and axon emerge from the same process

- Bipolar: The cell has a single axon and a single dendrite on opposite ends of the soma

- Multipolar: The cell contains more than two dendrites

- Golgi I: Neurons with long-projecting axonal processes

- Golgi II: Neurons whose axonal process projects locally

Some unique neuronal types can be identified according to their location in the nervous system and their distinct shape. Examples include basket, Betz, medium spiny, Purkinje, pyramidal, and Renshaw cells.

Functional classifications

Classification by connectivity

- Afferent neurons convey information from tissues and organs into the central nervous system.

- Efferent neurons transmit signals from the central nervous system to the effector cells and are sometimes called motor neurons.

- Interneurons connect neurons within specific regions of the central nervous system.

The terms afferent and efferent can also refer to neurons which convey information from one region of the brain to another.

Classification by action on other neurons

- Excitatory neurons evoke excitation of their target neurons. Excitatory neurons in the brain are often glutamatergic. Spinal motor neurons use acetylcholine as their neurotransmitter.

- Inhibitory neurons evoke inhibition of their target neurons. Inhibitory neurons are often interneurons. The output of some brain structures (for example, neostriatum, globus pallidus, cerebellum) are inhibitory. The primary inhibitory neurotransmitters are GABA and glycine.

- Modulatory neurons evoke more complex effects termed neuromodulation. These neurons use such neurotransmitters as dopamine, acetylcholine, serotonin, and others.

Classification by discharge patterns

Neurons can be classified according to their electrophysiological characteristics:

- Tonic or regular spiking: some neurons are typically constantly (or tonically) active

- Phasic or bursting: Neurons that fire in bursts

- Fast spiking: Some neurons are notable for their fast firing rates

- Thin-spike: Action potentials of some neurons are narrower than others

Classification by neurotransmitter released

Examples include cholinergic, GABA-ergic, glutamatergic, and dopaminergic neurons.

Notes

- ↑ Wei-Chung Allen Lee, Hayden Huang, Guoping Feng, Joshua R. Sanes, Emery N. Brown, Peter T. So, and Elly Nedivi, Dynamic Remodeling of Dendritic Arbors in GABAergic Interneurons of Adult Visual Cortex, PLoS Biology. Retrieved August 28, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bullock, T. H., M. V. L. Bennett, D. Johnston, R. Josephson, E. Marder, and R. D. Fields. 2005. “The Neuron Doctrine, Redux.” Science 310: 791-793.

- Connors, B., and M. Long. 2004. “Electrical synapses in the mammalian brain.” Annu Rev Neurosci 27: 393-418. PMID 15217338.

- Djurisic, M., S. Antic, W. Chen, and D. Zecevic. 2004. “Voltage imaging from dendrites of mitral cells: EPSP attenuation and spike trigger zones.” J Neurosci 24(30): 6703-6714. PMID 15282273.

- Kandel, E. R., J. H. Schwartz, and T. M. Jessell. 2000. Principles of Neural Science, 4th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0838577016.

- Lodish, H., D. Baltimore, A. Berk, S. L. Zipursky, P. Matsudaira, and J. Darnell. 1995. Molecular Cell Biology, 3rd edition. New York: Scientific American Books. ISBN 0716723808.

- Marieb, E. N. and K. Hoehn. 2010. Human Anatomy & Physiology, 8th edition. Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 9780805395693.

- Peters, A., S. L. Palay, and H. D. Webster. 1991. The Fine Structure of the Nervous System: Neurons and Their Supporting Cells, 3rd edition. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195065719.

- Ramón y Cajal, S. 1933. Histology, 10th edition. Baltimore, MD: Wood.

- Roberts, A., and B. M. H. Bush. 1981. Neurones Without Impulses: Their Significance for Vertebrate and Invertebrate Nervous Systems. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052123364X.

- Sabbatini, R. M. E. 2003. “Neurons and synapses: The history of its discovery.” Brain & Mind Magazine 17. Retrieved August 28, 2007.

- Witcher, M., S. Kirov, and K. Harris. 2007. “Plasticity of perisynaptic astroglia during synaptogenesis in the mature rat hippocampus.” Glia 55(1): 13-23.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.