Difference between revisions of "Naga" - New World Encyclopedia

Scott Dunbar (talk | contribs) (Imported and credited article from Wikipedia) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (22 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Paid}} |

| − | [[Image:Laonaga.JPG|thumb|200px|A naga guarding the Temple of | + | [[Image:Laonaga.JPG|thumb|200px|A naga guarding the Temple of Wat Sisaket in Vientiane, Laos.]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | '''Nāga''' ([[Sanskrit]]:{{unicode|नाग}}) refers to a race of large serpentine creatures that abound in the mythologies of [[Hinduism]] and [[Buddhism]]. Although these creatures are occassionally portrayed negatively in both traditions, they are generally held in high regard, as they represent fertility and steadfastness. They are also closely associated with notions of kingship throughout several South Asian nations. They are even the object of some cult devotion, particularly in Southern India. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Lingam.jpg|thumb|An open-air [[Lingam]] (symbol of God [[Shiva]]) from [[Lepakshi]] sheltered by a naga.]] | |

| − | + | In Sanskrit, the term '''{{IAST|nāgaḥ}}''' ({{lang|sa|नागः}}) refers specifically to a cobra, the hooded snake. In fact, the Indian Cobra is still called nāg in Hindi and other [[language]]s of India today. Thus, the use of the term '''nāga''' is often ambiguous, as the word may also refer not only to the mythological serpents, but also, in similar contexts, to ordinary snakes, or to one of several human tribes known as or nicknamed "Nāgas."<ref>For the specific terminology for cobra see Vaman Shivram Apte, ''The Student's English-Sanskrit Dictionary'' (Motilal Banarsidass: 2002 reprint edition, ISBN 81-208-0299-3), 432.</ref> A female nāga is a '''nāgī'''. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Nāgas in Hinduism== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Stories involving the nāgas are still very much a part of contemporary cultural traditions in predominantly Hindu regions of [[Asia]], including [[India]], [[Nepal]], and the island of [[Bali]]. In the Hindu fold, nāgas are considered nature spirits, protecting bodies of water such as rivers, lakes, seas, springs, and wells. If properly worshipped, they bring rain, and with it wealth and fertility. However, they are also thought to bring disasters such as floods, famine and drought if they are slighted by humankind's disrespectful actions in relation to the environment, since such actions impinge upon their natural habitats. | |

| − | [[ | + | |

| + | Perhaps the most famous naga in the Hindu tradition is Shesha, who is most recognizable by way of his hundred heads. He is often portrayed along with [[Vishnu]], who is either sheltered by or reclined upon him. [[Balarama]], brother of Vishnu's incarnation Krishna (who is sometimes considered an [[avatar]] himself), has also sometimes been identified as an incarnation of Shesha. The serpent is not exclusively linked with Vishnu, and is also a common feature in the iconography of [[Ganesha]] and Shiva. In the case of Ganesha, the serpent is usually depicted draped around the neck or around the belly of the god, or else wrapped around the stomach as a belt, held in a hand, coiled at the ankles, or as a throne. One of Shiva's most identifiable features is the snake garlanded around his neck, and Shiva [[linga]]s are often shown sheltered by the many heads of the naga. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Nagas in the Mahabharata=== | ||

| − | + | The Nagas make numerous appearances in the great Hindu epic called the ''[[Mahabharata]]'', though their depiction tends to be negative, and they are portrayed as the deserving victims of misfortune on several occasions. However, nagas are important players in many of the events narrated in the epic, demonstrating themselves to be no more evil nor deceitful than the epic's protagonists. The Mahabharata frequently characterizes Nagas as having a mixture of human and serpent-like traits. For example, the story of how the Naga prince Shesha came to hold the world on his head begins with a scene in which he appears as a dedicated human ascetic. [[Brahman]] is pleased with Shesha, and entrusts him with the duty of carrying the world. From that point on, Shesha begins to exhibit the attributes of a serpent, entering into a hole in the Earth and slithering all the way to its bottom, where he then loads the Earth onto his head.<ref>Book I: Adi Parva, Section 36.</ref> | |

| − | + | One of the more famous tales found in the Mahabharata involves the churning of the milk ocean, which is found in Section 18, Book I of the Adi Parva (in addition to the Kurma Purana). Here the gods and the asuras work together to churn the milk ocean in hopes of mixing together the elixir of immortality. The naga king Vasuki helped the gods in their task by serving as the churning rope—after wrapping the snake around the massive Mount Mandara, the devas pulled him first one way and then the other in order to stir up the depths of the ocean. | |

| − | + | The Mahabharata establishes the gigantic bird-man [[Garuda]] as the great nemesis of the Nagas. Ironically, Garuda and the Nagas actually begin life as cousins. The sage Kasyapa had two wives, Kadru and Vinata, the former of whom desired many offspring, and the latter of whom desired only a few children, albeit powerful ones. Each woman's wish was granted: Kadru laid a thousand eggs, which hatched into the nagas, and Vinata laid but two, which hatched into Garuda as well as the sun god [[Surya]]'s charioteer. Kadru went on to make a bet with her sister Vinata, with the overarching condition being that the loser would be enslaved to the winner. | |

| − | The | + | Anxious to secure victory, Kadru requested the cooperation of the Nagas in order to fix the bet so that she would win. When her offspring balked at the request, Kadru grew angry and cursed them to die a fiery death in the snake-sacrifice of King Janamejaya. The king of the snakes Vasuki was aware of the curse, and knew that his brethren would need a hero to rescue them from it. He approached the renowned ascetic Jaratkaru with a proposal of marriage to a snake-maiden, Vasuki's own sister. Out of the union of the ascetic and the snake-maiden was born a son by the name of Astika, and he was to be the savior of the snakes. In accordance with Kadru's curse, Janamejaya prepared a snake sacrifice as it was prescribed in the scriptures, erecting a sacrificial platform and acquiring priests who were necessary for the rites. Following the proper procedure, the priests lit the sacrificial fire, duly fed it with clarified butter, uttered the required [[mantra]]s, and began calling the names of snakes. The power of the rite was such that the named snakes were summoned to the fire and promptly consumed by it. As the sacrifice took on genocidal proportions, Astika came to the rescue. He approached Janamejaya and praised the sacrifice in such eloquent terms that the king offered to grant him a boon of his choosing. Astika promptly asked that the sacrifice be terminated, and Janamejaya, initially regretful, honored the request.<ref>Book I: Adi Parva, Sections 13-58.</ref> |

| − | + | Nonetheless, Kadru wound up winning the bet and Vinata became enslaved to her victorious sister. As a result, Vinata's son Garuda was also required to do the bidding of the snakes. Though compliant, he built up a considerable grudge against his masters, one that he would never relinquish. When he asked the nagas what he would have to do in order to release himself and his mother from their bondage, they suggested that he bring them amrita, the elixir of immortality which was in the possession of the gods in heaven, chiefly [[Indra]]. Garuda deftly stole the elixir from the gods and brought it to the anxiously waiting nagas, fulfilling their request. Upon handing them the pot of nectar, Garuda requested that they cover it with sharp, spiky Darbha grass while taking their purificatory bath. Placing the elixir on the grass, and thereby liberating his mother Vinata from her servitude, Garuda urged the serpents to perform their religious ablutions before consuming it. As the nagas hurried off to do so, Indra descended from the sky and made off with the elixir, returning it to heaven. When the nagas came back, they licked the darbha grass in the absence of the pot, hoping to indulge in the power of the elixir. Instead their mouths were cut up by the knife-edged grass, and were left with the forked tounges characteristic of serpents. From that point onward, the nagas considered Garuda an enemy, while Garuda considered the nagas to be food. | |

| − | |||

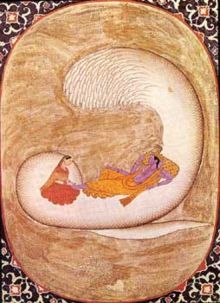

| − | + | [[Image:Anantavishnu.jpg|thumb|220px|[[Vishnu]] resting on Ananta-[[Shesha]], with consort [[Lakshmi]].]] | |

| − | + | ===Worship=== | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Nagas are objects of great reverence in some branches of India, particularly those located in southern [[India]], where it is believed that they bring fertility and prosperity to their worshippers. Hence, expensive and grand rituals are conducted in their honour, one of the foremost being Nagamandala. This festival begins in conjunction with the monsoon season in Coastal Karnataka and Kerala and commemorates the significance of the serpent as a symbol of fertility and overall well-being. The ritual is carried out by two groups of performers: the 'paatri' (a Brahmin) who becomes possessed by the cobra god after inhaling areca flowers, and the Naagakannika, a male dressed in the disguise of a female serpent. This character sings and dances around an intricate serpent design drawn upon the ground in five different colors. This dance lasts all throughout the night while Brahmins utter mantras in Sanskrit. | |

==Nāgas in Buddhism== | ==Nāgas in Buddhism== | ||

| − | [[Image:Buddha with Naga (snake).jpg|thumb|left|Mucalinda shethering [[Gautama Buddha]]; Wall-Painting from monastery in [[Laos]] | + | [[Image:Buddha with Naga (snake).jpg|thumb|left|Mucalinda shethering [[Gautama Buddha]]; Wall-Painting from monastery in [[Laos]].]] |

| − | |||

| − | The Buddhist nāga generally has the form of a large | + | The Buddhist nāga generally has the form of a large cobra-like snake, usually with a single head but sometimes pictured with a multiplicity. At least some of the nāgas are capable of using magic powers to transform themselves into a human semblance. Accordingly, in some Buddhist paintings, the nāga is portrayed as a human being with a snake or dragon extending over his head. In these anthropomorphic forms, cobra heads often spring from the neck. The Buddha is often shown conquering the nagas, probably a suggestion of his unsurpassed ability to overcome the natural world by way of his perfected virtues. Candidates for monkhood must also be able to tame their physical desires in a similar way if they wish to attain [[nirvana]]; accordingly, such candidates are called ''nag''. |

| − | Nāgas are believed to both live on Mount | + | Nāgas are believed to both live among the other minor dieties on Mount Sumeru, the central world-mountain of Buddhist cosmology deities, where they stand on guard against the malevolent asuras. Here they also assume the role servants to {{IAST|Virūpākṣa}} (Pāli: Virūpakkha), guardian of the western direction and one of the Four Heavenly Kings. Alternatively, Nagas are said to make their homes in various parts of the human-inhabited earth. Some of them are water-dwellers, living in rivers or the ocean; others are earth-dwellers, living in underground caverns, roots of trees, or in anthills, all of which are held to be thresholds leading to the underworld. |

| − | + | Among the notable figures of Buddhist tradition related to nāgas are Mucalinda and [[Nagarjuna]]. Mucalinda, a naga king, is the protector of the Buddha, and in artistic and mythological illustrations he is commonly shown sheltering the post-nirvana Buddha from the elements by way of his many heads. According to tradition the [[Prajnaparamita]] teachings are held to have been conferred upon Nagarjuna by Nagaraja, the King of the nagas, who had been guarding them at the bottom of the [[ocean]]. Similarly, followers of the Chinese Hua-Yen tradition believe that Nagarjuna swam to the bottom of this great body of water and brought back the fundamental teachings (crystallized for this tradition in the ''Avatamsaka Sutra'') and brought them to the surface to disseminate among human beings. Nagarjuna's name itself derives from the conjunction of the word ''naga'' (serpent) with ''arjuna'', meaning "bright" or "shining"—thus, Nagarjuna is literally the "resplendent Naga." | |

| − | + | Traditions concerning nāgas have become characteristic of all the Buddhist countries of Asia. In many countries, the nāga concept has been merged with local traditions of large and intelligent serpents or dragons. In [[Tibet]], for instance, the nāga was equated with the ''klu'' (pronounced ''lu''), [[spirit]]s that dwell in lakes or underground streams and guard treasure. Similarly, in [[China]] the nāga was equated with the ''lóng'' or Chinese dragon. | |

| − | == | + | ==Other nāga traditions== |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Nāgas in Cambodia=== | |

| − | + | [[Image:NagaPhnomPenh.jpg|thumb|230px|right|Cambodian Naga at the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh.]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | According to [[Cambodia|Cambodian]] legend, the nāga were a race of reptilian beings who possessed a large empire in the [[Pacific Ocean]] region. The Nāga King's daughter married an Indian Brahmin named Kaundinya, and from their union sprang the Cambodian people; accordingly, Cambodians today claim that they are "Born from the Nāga." The Seven-Headed Nāga serpents depicted as statues on Cambodian temples, such as those at [[Angkor Wat]], apparently represent the seven races within Nāga society which has a symbolic association with the Cambodian concept of "the seven colors of the rainbow." Furthermore, the number of heads on the Cambodian Nāga possess numerological symbolism: Nāgas depicted with an odd number of heads symbolise the infinite, timeless and immortal male energy, because numerologically, all odd numbers are said to rely on the number one. Nāgas depicted with an even number of heads are said to be female, representing the opposite characteristics of physicality, mortality, temporality, and the Earth. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Naga in Lake Chinni=== | ===Naga in Lake Chinni=== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In the Malaysian and Orang Asli traditions, nāgas are a variation of the dragon which is distinguishable by its many heads. Sailors are particularly wary when traveling the lake Chinni located in Pahang, which is said to be home to a nāgī called Sri Gumum. According to certain variations of this legend, her predecessor Sri Pahang or else her son left the lake and later fought a naga by the name of Sri Kemboja. Interestingly enough, Kemboja is the former name of what is now Cambodia. | |

===Nāgas in the Mekong=== | ===Nāgas in the Mekong=== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The legend of the Nāga is a belief strongly held by the Lao and Thai people living along the Mekong River. In [[Thailand]], the nāga is a wealthy underworld deity. In [[Laos]], by contrast, nagas are beaked water serpents. Many members of all three cultures pay their respects to the river because they believe the Nāga or nāgas still rule over it, and river folk hold annual sacrifices for its benefit. Local residents believe that the Nāga can protect them from danger, so it is not uncommon for them to make a sacrifice to Nāga before taking a boat trip along the Mekong River. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In addition, every year on the night of 15th day of the 11th month in the Lao lunar calendar, an extraordinary phenomenon occurs in the area of the Mekong River stretching over 20 kilometers between Pak-Ngeum district, about 80 kilometers south of the Lao capital Vientiane, and Phonephisai district in Nong Khai province; that is, hundreds of red, pink and orange fireballs spew up from the river. While scientists attribute this occurrence to the emission of natural gasses from the [[plant]] and [[animal]] life decomposing at the bottom of the river, villagers on both sides of the river have their own ideas as to the origin of the fireballs. They refer to this phenomenon "Nāga's Fireball," and believe the Nāga under Mekong River shoot fireballs into the air to celebrate the end of the annual retreat known in Thai as "Phansa" (Buddhist Lent), since the Nāga also meditate during this period of time. A two-day celebration involving a boat race as well as light and sound shows now accompanies the yearly spectacle.<ref>[http://www.istc.org/sisp/index.htm?fx=event&event_id=95377 Naga Fireballs at Nong Khai Province] Retrieved March 12, 2008.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 125: | Line 66: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * | + | * Beer, Robert. 1999. ''The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs'' (Hardcover). Shambhala. ISBN 157062416X |

| − | * | + | * Bloss, Lowell W. "Nagas and Yakshas." In ''The Encyclopedia of Religion''. Volume 9. Ed. Lindsay Jones. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005. ISBN 002865742X |

| − | * | + | * Maehle, Gregor. 2007. ''Ashtanga Yoga: Practice and Philosophy''. New World Library. ISBN 1577316061 |

| − | + | * Müller-Ebeling, Claudia, Christian Rätsch and Surendra Bahadur Shahi. 2002. ''Shamanism and Tantra in the Himalayas''. Transl. by Annabel Lee. Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions. | |

| + | * Norbu, Chögyal Namkhai. 1999. ''The Crystal and The Way of Light: Sutra, Tantra and Dzogchen''. Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 1-55939-135-9 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved November 10, 2022. | ||

| + | |||

*[http://www.palikanon.com/english/pali_names/n/nagaa.htm Nagas in the Pali Canon] | *[http://www.palikanon.com/english/pali_names/n/nagaa.htm Nagas in the Pali Canon] | ||

*[http://www.khandro.net/mysterious_naga.htm Nagas] | *[http://www.khandro.net/mysterious_naga.htm Nagas] | ||

| − | |||

*[http://www.reptilianagenda.com/research/r073101a.shtml Nagas and Serpents] | *[http://www.reptilianagenda.com/research/r073101a.shtml Nagas and Serpents] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{HinduMythology}} | {{HinduMythology}} | ||

Latest revision as of 23:09, 10 November 2022

Nāga (Sanskrit:नाग) refers to a race of large serpentine creatures that abound in the mythologies of Hinduism and Buddhism. Although these creatures are occassionally portrayed negatively in both traditions, they are generally held in high regard, as they represent fertility and steadfastness. They are also closely associated with notions of kingship throughout several South Asian nations. They are even the object of some cult devotion, particularly in Southern India.

Etymology

In Sanskrit, the term nāgaḥ (नागः) refers specifically to a cobra, the hooded snake. In fact, the Indian Cobra is still called nāg in Hindi and other languages of India today. Thus, the use of the term nāga is often ambiguous, as the word may also refer not only to the mythological serpents, but also, in similar contexts, to ordinary snakes, or to one of several human tribes known as or nicknamed "Nāgas."[1] A female nāga is a nāgī.

Nāgas in Hinduism

Stories involving the nāgas are still very much a part of contemporary cultural traditions in predominantly Hindu regions of Asia, including India, Nepal, and the island of Bali. In the Hindu fold, nāgas are considered nature spirits, protecting bodies of water such as rivers, lakes, seas, springs, and wells. If properly worshipped, they bring rain, and with it wealth and fertility. However, they are also thought to bring disasters such as floods, famine and drought if they are slighted by humankind's disrespectful actions in relation to the environment, since such actions impinge upon their natural habitats.

Perhaps the most famous naga in the Hindu tradition is Shesha, who is most recognizable by way of his hundred heads. He is often portrayed along with Vishnu, who is either sheltered by or reclined upon him. Balarama, brother of Vishnu's incarnation Krishna (who is sometimes considered an avatar himself), has also sometimes been identified as an incarnation of Shesha. The serpent is not exclusively linked with Vishnu, and is also a common feature in the iconography of Ganesha and Shiva. In the case of Ganesha, the serpent is usually depicted draped around the neck or around the belly of the god, or else wrapped around the stomach as a belt, held in a hand, coiled at the ankles, or as a throne. One of Shiva's most identifiable features is the snake garlanded around his neck, and Shiva lingas are often shown sheltered by the many heads of the naga.

Nagas in the Mahabharata

The Nagas make numerous appearances in the great Hindu epic called the Mahabharata, though their depiction tends to be negative, and they are portrayed as the deserving victims of misfortune on several occasions. However, nagas are important players in many of the events narrated in the epic, demonstrating themselves to be no more evil nor deceitful than the epic's protagonists. The Mahabharata frequently characterizes Nagas as having a mixture of human and serpent-like traits. For example, the story of how the Naga prince Shesha came to hold the world on his head begins with a scene in which he appears as a dedicated human ascetic. Brahman is pleased with Shesha, and entrusts him with the duty of carrying the world. From that point on, Shesha begins to exhibit the attributes of a serpent, entering into a hole in the Earth and slithering all the way to its bottom, where he then loads the Earth onto his head.[2]

One of the more famous tales found in the Mahabharata involves the churning of the milk ocean, which is found in Section 18, Book I of the Adi Parva (in addition to the Kurma Purana). Here the gods and the asuras work together to churn the milk ocean in hopes of mixing together the elixir of immortality. The naga king Vasuki helped the gods in their task by serving as the churning rope—after wrapping the snake around the massive Mount Mandara, the devas pulled him first one way and then the other in order to stir up the depths of the ocean.

The Mahabharata establishes the gigantic bird-man Garuda as the great nemesis of the Nagas. Ironically, Garuda and the Nagas actually begin life as cousins. The sage Kasyapa had two wives, Kadru and Vinata, the former of whom desired many offspring, and the latter of whom desired only a few children, albeit powerful ones. Each woman's wish was granted: Kadru laid a thousand eggs, which hatched into the nagas, and Vinata laid but two, which hatched into Garuda as well as the sun god Surya's charioteer. Kadru went on to make a bet with her sister Vinata, with the overarching condition being that the loser would be enslaved to the winner.

Anxious to secure victory, Kadru requested the cooperation of the Nagas in order to fix the bet so that she would win. When her offspring balked at the request, Kadru grew angry and cursed them to die a fiery death in the snake-sacrifice of King Janamejaya. The king of the snakes Vasuki was aware of the curse, and knew that his brethren would need a hero to rescue them from it. He approached the renowned ascetic Jaratkaru with a proposal of marriage to a snake-maiden, Vasuki's own sister. Out of the union of the ascetic and the snake-maiden was born a son by the name of Astika, and he was to be the savior of the snakes. In accordance with Kadru's curse, Janamejaya prepared a snake sacrifice as it was prescribed in the scriptures, erecting a sacrificial platform and acquiring priests who were necessary for the rites. Following the proper procedure, the priests lit the sacrificial fire, duly fed it with clarified butter, uttered the required mantras, and began calling the names of snakes. The power of the rite was such that the named snakes were summoned to the fire and promptly consumed by it. As the sacrifice took on genocidal proportions, Astika came to the rescue. He approached Janamejaya and praised the sacrifice in such eloquent terms that the king offered to grant him a boon of his choosing. Astika promptly asked that the sacrifice be terminated, and Janamejaya, initially regretful, honored the request.[3]

Nonetheless, Kadru wound up winning the bet and Vinata became enslaved to her victorious sister. As a result, Vinata's son Garuda was also required to do the bidding of the snakes. Though compliant, he built up a considerable grudge against his masters, one that he would never relinquish. When he asked the nagas what he would have to do in order to release himself and his mother from their bondage, they suggested that he bring them amrita, the elixir of immortality which was in the possession of the gods in heaven, chiefly Indra. Garuda deftly stole the elixir from the gods and brought it to the anxiously waiting nagas, fulfilling their request. Upon handing them the pot of nectar, Garuda requested that they cover it with sharp, spiky Darbha grass while taking their purificatory bath. Placing the elixir on the grass, and thereby liberating his mother Vinata from her servitude, Garuda urged the serpents to perform their religious ablutions before consuming it. As the nagas hurried off to do so, Indra descended from the sky and made off with the elixir, returning it to heaven. When the nagas came back, they licked the darbha grass in the absence of the pot, hoping to indulge in the power of the elixir. Instead their mouths were cut up by the knife-edged grass, and were left with the forked tounges characteristic of serpents. From that point onward, the nagas considered Garuda an enemy, while Garuda considered the nagas to be food.

Worship

Nagas are objects of great reverence in some branches of India, particularly those located in southern India, where it is believed that they bring fertility and prosperity to their worshippers. Hence, expensive and grand rituals are conducted in their honour, one of the foremost being Nagamandala. This festival begins in conjunction with the monsoon season in Coastal Karnataka and Kerala and commemorates the significance of the serpent as a symbol of fertility and overall well-being. The ritual is carried out by two groups of performers: the 'paatri' (a Brahmin) who becomes possessed by the cobra god after inhaling areca flowers, and the Naagakannika, a male dressed in the disguise of a female serpent. This character sings and dances around an intricate serpent design drawn upon the ground in five different colors. This dance lasts all throughout the night while Brahmins utter mantras in Sanskrit.

Nāgas in Buddhism

The Buddhist nāga generally has the form of a large cobra-like snake, usually with a single head but sometimes pictured with a multiplicity. At least some of the nāgas are capable of using magic powers to transform themselves into a human semblance. Accordingly, in some Buddhist paintings, the nāga is portrayed as a human being with a snake or dragon extending over his head. In these anthropomorphic forms, cobra heads often spring from the neck. The Buddha is often shown conquering the nagas, probably a suggestion of his unsurpassed ability to overcome the natural world by way of his perfected virtues. Candidates for monkhood must also be able to tame their physical desires in a similar way if they wish to attain nirvana; accordingly, such candidates are called nag.

Nāgas are believed to both live among the other minor dieties on Mount Sumeru, the central world-mountain of Buddhist cosmology deities, where they stand on guard against the malevolent asuras. Here they also assume the role servants to Virūpākṣa (Pāli: Virūpakkha), guardian of the western direction and one of the Four Heavenly Kings. Alternatively, Nagas are said to make their homes in various parts of the human-inhabited earth. Some of them are water-dwellers, living in rivers or the ocean; others are earth-dwellers, living in underground caverns, roots of trees, or in anthills, all of which are held to be thresholds leading to the underworld.

Among the notable figures of Buddhist tradition related to nāgas are Mucalinda and Nagarjuna. Mucalinda, a naga king, is the protector of the Buddha, and in artistic and mythological illustrations he is commonly shown sheltering the post-nirvana Buddha from the elements by way of his many heads. According to tradition the Prajnaparamita teachings are held to have been conferred upon Nagarjuna by Nagaraja, the King of the nagas, who had been guarding them at the bottom of the ocean. Similarly, followers of the Chinese Hua-Yen tradition believe that Nagarjuna swam to the bottom of this great body of water and brought back the fundamental teachings (crystallized for this tradition in the Avatamsaka Sutra) and brought them to the surface to disseminate among human beings. Nagarjuna's name itself derives from the conjunction of the word naga (serpent) with arjuna, meaning "bright" or "shining"—thus, Nagarjuna is literally the "resplendent Naga."

Traditions concerning nāgas have become characteristic of all the Buddhist countries of Asia. In many countries, the nāga concept has been merged with local traditions of large and intelligent serpents or dragons. In Tibet, for instance, the nāga was equated with the klu (pronounced lu), spirits that dwell in lakes or underground streams and guard treasure. Similarly, in China the nāga was equated with the lóng or Chinese dragon.

Other nāga traditions

Nāgas in Cambodia

According to Cambodian legend, the nāga were a race of reptilian beings who possessed a large empire in the Pacific Ocean region. The Nāga King's daughter married an Indian Brahmin named Kaundinya, and from their union sprang the Cambodian people; accordingly, Cambodians today claim that they are "Born from the Nāga." The Seven-Headed Nāga serpents depicted as statues on Cambodian temples, such as those at Angkor Wat, apparently represent the seven races within Nāga society which has a symbolic association with the Cambodian concept of "the seven colors of the rainbow." Furthermore, the number of heads on the Cambodian Nāga possess numerological symbolism: Nāgas depicted with an odd number of heads symbolise the infinite, timeless and immortal male energy, because numerologically, all odd numbers are said to rely on the number one. Nāgas depicted with an even number of heads are said to be female, representing the opposite characteristics of physicality, mortality, temporality, and the Earth.

Naga in Lake Chinni

In the Malaysian and Orang Asli traditions, nāgas are a variation of the dragon which is distinguishable by its many heads. Sailors are particularly wary when traveling the lake Chinni located in Pahang, which is said to be home to a nāgī called Sri Gumum. According to certain variations of this legend, her predecessor Sri Pahang or else her son left the lake and later fought a naga by the name of Sri Kemboja. Interestingly enough, Kemboja is the former name of what is now Cambodia.

Nāgas in the Mekong

The legend of the Nāga is a belief strongly held by the Lao and Thai people living along the Mekong River. In Thailand, the nāga is a wealthy underworld deity. In Laos, by contrast, nagas are beaked water serpents. Many members of all three cultures pay their respects to the river because they believe the Nāga or nāgas still rule over it, and river folk hold annual sacrifices for its benefit. Local residents believe that the Nāga can protect them from danger, so it is not uncommon for them to make a sacrifice to Nāga before taking a boat trip along the Mekong River.

In addition, every year on the night of 15th day of the 11th month in the Lao lunar calendar, an extraordinary phenomenon occurs in the area of the Mekong River stretching over 20 kilometers between Pak-Ngeum district, about 80 kilometers south of the Lao capital Vientiane, and Phonephisai district in Nong Khai province; that is, hundreds of red, pink and orange fireballs spew up from the river. While scientists attribute this occurrence to the emission of natural gasses from the plant and animal life decomposing at the bottom of the river, villagers on both sides of the river have their own ideas as to the origin of the fireballs. They refer to this phenomenon "Nāga's Fireball," and believe the Nāga under Mekong River shoot fireballs into the air to celebrate the end of the annual retreat known in Thai as "Phansa" (Buddhist Lent), since the Nāga also meditate during this period of time. A two-day celebration involving a boat race as well as light and sound shows now accompanies the yearly spectacle.[4]

Notes

- ↑ For the specific terminology for cobra see Vaman Shivram Apte, The Student's English-Sanskrit Dictionary (Motilal Banarsidass: 2002 reprint edition, ISBN 81-208-0299-3), 432.

- ↑ Book I: Adi Parva, Section 36.

- ↑ Book I: Adi Parva, Sections 13-58.

- ↑ Naga Fireballs at Nong Khai Province Retrieved March 12, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beer, Robert. 1999. The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs (Hardcover). Shambhala. ISBN 157062416X

- Bloss, Lowell W. "Nagas and Yakshas." In The Encyclopedia of Religion. Volume 9. Ed. Lindsay Jones. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005. ISBN 002865742X

- Maehle, Gregor. 2007. Ashtanga Yoga: Practice and Philosophy. New World Library. ISBN 1577316061

- Müller-Ebeling, Claudia, Christian Rätsch and Surendra Bahadur Shahi. 2002. Shamanism and Tantra in the Himalayas. Transl. by Annabel Lee. Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions.

- Norbu, Chögyal Namkhai. 1999. The Crystal and The Way of Light: Sutra, Tantra and Dzogchen. Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 1-55939-135-9

External links

All links retrieved November 10, 2022.

| Hinduism | Hindu mythology | Indian epic poetry | |

|---|---|

| Female Deities: Devi | Saraswati | Lakshmi | Sati | Parvati | Durga | Shakti | Kali | Sita | Radha | Mahavidya | more... | |

| Male Deities: Deva | Brahma | Vishnu | Shiva | Rama | Krishna | Ganesha | Murugan | Hanuman | Indra | Surya | more... | |

| Texts: Vedas | Upanishads | Puranas | Ramayana | Mahabharata | Bhagavad Gita | |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.