Difference between revisions of "Max Weber" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

[[Image:Max_Weber.jpg|thumb|right|Max Weber]] | [[Image:Max_Weber.jpg|thumb|right|Max Weber]] | ||

| − | '''Maximilian Weber''' (April 21, 1864 – June 14, 1920) was a [[Germany|German]] [[political economy|political economist]] and [[sociology|sociologist]] who is considered one of the founders of the modern, | + | '''Maximilian Weber''' (April 21, 1864 – June 14, 1920) was a [[Germany|German]] [[political economy|political economist]] and [[sociology|sociologist]] who is considered one of the founders of the modern, "antipositivistic" study of sociology and [[public administration]]. His major works deal with [[Rationalization (sociology)|rationalization]] in [[sociology of religion]] and [[Political sociology|government]], but he also wrote much in the field of [[economics]]. His most recognized work is his essay ''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism'', which began his work in the sociology of [[religion]]. Weber argued that religion was one of the primary reasons for the different ways the cultures of the [[Occident]] and the [[Orient]] have developed. |

==Life and career== | ==Life and career== | ||

| − | Weber was born in [[Erfurt]], [[Germany]], the eldest of seven children of Max Weber Sr., a prominent [[politician]] and [[civil service|civil servant]], and his wife Helene Fallenstein. His younger brother | + | Weber was born in [[Erfurt]], [[Germany]], the eldest of seven children of Max Weber Sr., a prominent [[politician]] and [[civil service|civil servant]], and his wife Helene Fallenstein. His younger brother, Alfred, was also a sociologist and economist. Weber grew up in a household immersed in [[politics]], and his father received a long list of prominent scholars and public figures in his salon. At the time, Weber proved to be intellectually precocious. [[Image:Max_weber_and_brothers_1879.jpg|thumb|left|Max Weber and his brothers Alfred and Karl in 1879.]] |

| − | In 1882 Weber enrolled in the [[University of Heidelberg]] as a [[law]] student. Weber chose as his major study his father's field of law. Apart from his work in law, he attended lectures in | + | In 1882 Weber enrolled in the [[University of Heidelberg]] as a [[law]] student. Weber chose as his major study his father's field of law. Apart from his work in law, he attended lectures in economics and studied [[medieval history]]. In addition, Weber read a great deal in [[theology]]. In the fall of 1884 Weber returned to his parents' home to study at the [[University of Berlin]]. In 1886 Weber passed the examination for "Referendar", comparable to the [[bar association|bar]] examination in the [[United States|American]] [[legal system]]. He earned his doctorate in law in 1889 by writing a doctoral dissertation on legal history entitled ''The History of Medieval Business Organisations''. |

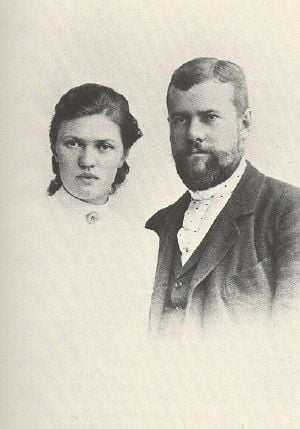

[[Image:Max and marienne weber 1894.jpg|thumb|Max Weber and his wife Marianne in 1894.]] | [[Image:Max and marienne weber 1894.jpg|thumb|Max Weber and his wife Marianne in 1894.]] | ||

| − | In 1893 he married his distant | + | In 1893 he married his distant cousin Marianne Schnitger, later a [[feminism|feminist]] and [[author]] in her own right, who after his death in 1920 was decisive in collecting and publishing Weber's works as books. In 1894 the couple moved to Freiburg, where Weber was appointed professor of economics at [[Albert-Ludwigs-Universität|Freiburg University]], before accepting the same position at the [[University of Heidelberg]] in 1897. The same year his father died two months after a severe quarrel with him. Following this incident Weber was more and more prone to "nervousness" and insomnia. He spent several months in a sanatorium in the summer and fall of 1900. |

| − | After his immense productivity in the early 1890s he finally resigned as a professor in the fall of 1903. In 1904 Max Weber began to publish some of his most seminal papers in this journal, notably his essay ''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism''. It became his most famous work, and laid the foundations for his later research on the impact of [[culture]]s and [[religion]]s on the development of [[economic | + | After his immense productivity in the early 1890s he finally resigned as a professor in the fall of 1903. In 1904 Max Weber began to publish some of his most seminal papers in this journal, notably his essay ''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism''. It became his most famous work, and laid the foundations for his later research on the impact of [[culture]]s and [[religion]]s on the development of [[economic systems]]. |

[[Image:Max weber in 1917.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Max Weber in 1917.]] | [[Image:Max weber in 1917.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Max Weber in 1917.]] | ||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

Weber thought that the only way that German culture would survive was by creating an empire. He influenced German policy towards Eastern Germany. In 1894 he proposed closing the border to [[Poland|Polish]] workers from [[Russia]] and [[Austria-Hungary]]. However, in 1895, impressed by the attitude of the Russian liberal party, which wanted to change Russian [[nationalism]] by accepting ethnic minorities as Russians, he reversed his position. | Weber thought that the only way that German culture would survive was by creating an empire. He influenced German policy towards Eastern Germany. In 1894 he proposed closing the border to [[Poland|Polish]] workers from [[Russia]] and [[Austria-Hungary]]. However, in 1895, impressed by the attitude of the Russian liberal party, which wanted to change Russian [[nationalism]] by accepting ethnic minorities as Russians, he reversed his position. | ||

| − | Weber advocated [[democracy]] as a means for selecting strong leaders. He viewed democracy as a form of [[charismatic authority| | + | Weber advocated [[democracy]] as a means for selecting strong leaders. He viewed democracy as a form of [[charismatic authority|charisma]] where the "demagogue imposes his will on the masses." For this reason, the European left is highly critical of Weber for, albeit unwittingly, "preparing the intellectual groundwork for the leadership position of Adolf Hitler." |

Weber was strongly anti-socialist, despising the anti-nationalist stance of the Marxist parties. He was surprised that the communists in Russia (who dissolved the old elite and bureaucracy) could survive for more than half a year. | Weber was strongly anti-socialist, despising the anti-nationalist stance of the Marxist parties. He was surprised that the communists in Russia (who dissolved the old elite and bureaucracy) could survive for more than half a year. | ||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

==Achievements== | ==Achievements== | ||

| − | Max Weber was – along with [[Karl Marx]], [[Vilfredo Pareto]] and [[Émile Durkheim]] – one of the founders of modern sociology. Whereas Pareto and Durkheim, following [[Auguste Comte|Comte]], worked in the [[positivist]] tradition, Weber created and worked, like [[Werner Sombart]], in the | + | Max Weber was – along with [[Karl Marx]], [[Vilfredo Pareto]] and [[Émile Durkheim]] – one of the founders of modern sociology. Whereas Pareto and Durkheim, following [[Auguste Comte|Comte]], worked in the [[Positivism|positivist]] tradition, Weber created and worked, like [[Werner Sombart]], in the antipositivist, [[idealism|idealist]] and [[hermeneutics|hermeneutic]] tradition. Those works started the antipositivistic revolution in social sciences, which stressed the difference between the social sciences and natural sciences, especially due to human social actions. Weber's early work was related to industrial sociology, but he is most famous for his later work on the [[sociology of religion]] and sociology of government. |

| − | Max Weber began his studies of | + | Max Weber began his studies of Rationalization in ''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism'', in which he showed how the aims of certain [[Protestantism|Protestant]] [[Religious denomination|denomination]]s, particularly [[Calvinism]], shifted towards the rational means of economic gain as a way of expressing that they had been blessed. The rational roots of this doctrine, he argued, soon grew incompatible with and larger than the religious, and so the latter were eventually discarded. Weber continued his investigation into this matter in later works, notably in his studies on [[bureaucracy]] and on the classifications of [[authority]]. |

| − | == | + | == Theories == |

===Sociology of religion=== | ===Sociology of religion=== | ||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

His three main themes were the effect of religious ideas on economic activities, the relation between [[social stratification]] and religious ideas, and the distinguishable characteristics of Western civilization. | His three main themes were the effect of religious ideas on economic activities, the relation between [[social stratification]] and religious ideas, and the distinguishable characteristics of Western civilization. | ||

| − | His goal was to find reasons for the different development paths of the cultures of the Occident and the Orient. In the analysis of his findings, Weber maintained that [[Puritan]] (and more widely, | + | His goal was to find reasons for the different development paths of the cultures of the Occident and the Orient. In the analysis of his findings, Weber maintained that [[Puritan]] (and more widely, Protestant) religious ideas had had a major impact on the development of the economic system of [[Europe]] and the [[United States]], but noted that they were not the only factors in this development. Weber identified "disenchantment of the world" as an important distinguishing aspect of [[Western culture]]. |

====''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism''==== | ====''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism''==== | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

The answer was to be found in the religious ideas of the [[Protestant Reformation|Reformation]]. Weber argued that certain Protestant ideas favored rational pursuit of economic gain and worldly activities which had been given positive spiritual and moral meaning. Particularly, Calvin's understanding of predestination, namely that sinful people cannot know directly whether they are part of God's elect to whom the grace of salvation is offered, was taken by Weber as the key to solving the paradox. He argued that the resultant insecurity on the part of Protestants, and their fear of eternal damnation, led them to seek signs indicating God's direction for their lives and affirmation of their correct behavior. Thus, hard work followed by financial success came to be the hallmark of God's grace. Coupled with traditional religious asceticism, these ideas encouraged people to accumulate wealth. It was not the goal of those religious ideas, but rather a byproduct – the inherent logic of those doctrines and the advice based upon them both directly and indirectly encouraged planning and self-denial in the pursuit of economic gain. | The answer was to be found in the religious ideas of the [[Protestant Reformation|Reformation]]. Weber argued that certain Protestant ideas favored rational pursuit of economic gain and worldly activities which had been given positive spiritual and moral meaning. Particularly, Calvin's understanding of predestination, namely that sinful people cannot know directly whether they are part of God's elect to whom the grace of salvation is offered, was taken by Weber as the key to solving the paradox. He argued that the resultant insecurity on the part of Protestants, and their fear of eternal damnation, led them to seek signs indicating God's direction for their lives and affirmation of their correct behavior. Thus, hard work followed by financial success came to be the hallmark of God's grace. Coupled with traditional religious asceticism, these ideas encouraged people to accumulate wealth. It was not the goal of those religious ideas, but rather a byproduct – the inherent logic of those doctrines and the advice based upon them both directly and indirectly encouraged planning and self-denial in the pursuit of economic gain. | ||

| − | According to Weber, this "spirit of capitalism" not only involved hard work and [entrepreneur|entrepreneurism] on the part of Protestants, but also a sense of stewardship over the resulting gains. For if money is not sought after for luxury or self-indulgence, but as moral affirmation, economizing and reinvesting in worthy enterprises become normal economic practices. | + | According to Weber, this "spirit of capitalism" not only involved hard work and [[entrepreneur|entrepreneurism]] on the part of Protestants, but also a sense of stewardship over the resulting gains. For if money is not sought after for luxury or self-indulgence, but as moral affirmation, economizing and reinvesting in worthy enterprises become normal economic practices. |

Weber acknowledged that other factors, both material and psychological, contributed to the development of modern capitalism. He also agreed that previous capitalist societies existed prior to Calvinism. However, in those cases religious views did not support the capitalist enterprise but rather limited it. Only the Protestant ethic, based on Calvinism, actively supported the accumulation of capital as a sign of God's grace. | Weber acknowledged that other factors, both material and psychological, contributed to the development of modern capitalism. He also agreed that previous capitalist societies existed prior to Calvinism. However, in those cases religious views did not support the capitalist enterprise but rather limited it. Only the Protestant ethic, based on Calvinism, actively supported the accumulation of capital as a sign of God's grace. | ||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

==== ''The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism'' ==== | ==== ''The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism'' ==== | ||

| − | ''The Religion of China: | + | ''The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism'' was Weber's second major work on the sociology of religion. Weber focused on those aspects of [[China|Chinese]] society that were different from those of [[Western Europe]] and especially contrasted with Puritanism, and posed a question why capitalism did not develop in China. |

| − | As in Europe, Chinese cities had been founded as [[fort]]s or leaders' residences, and were the | + | As in Europe, Chinese cities had been founded as [[fortification|fort]]s or leaders' residences, and were the centers of [[trade]] and crafts. However, they never received political [[autonomy]] and its citizens had no special political rights or privileges. This is due to the strength of [[kinship]] ties, which stems from religious beliefs in ancestral spirits. Also, the [[guild]]s competed against each other for the favour of the [[Emperor]], never uniting in order to fight for more rights. Therefore, the residents of Chinese cities never constituted a separate status class like the residents of European cities. |

| − | Weber emphasized that instead of metaphysical conjectures, Confucianism taught adjustment to the world. The "superior" man ( | + | Weber emphasized that instead of metaphysical conjectures, [[Confucianism]] taught adjustment to the world. The "superior" man (literati) should stay away from the pursuit of wealth (though not from wealth itself). Therefore, becoming a [[civil service|civil servant]] was preferred to becoming a [[business]]man and granted a much higher status. |

Chinese civilization had no religious [[prophecy]] nor a powerful [[priest]]ly class. The emperor was the [[high priest]] of the [[state religion]] and the supreme ruler, but popular cults were also tolerated (however the political ambitions of their priests were curtailed). This forms a sharp contrast with medieval Europe, where the [[Church]] curbed the power of [[secularism|secular]] rulers and the same faith was professed by rulers and common folk alike. | Chinese civilization had no religious [[prophecy]] nor a powerful [[priest]]ly class. The emperor was the [[high priest]] of the [[state religion]] and the supreme ruler, but popular cults were also tolerated (however the political ambitions of their priests were curtailed). This forms a sharp contrast with medieval Europe, where the [[Church]] curbed the power of [[secularism|secular]] rulers and the same faith was professed by rulers and common folk alike. | ||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

====''The Religion of India: The Sociology of Hinduism and Buddhism''==== | ====''The Religion of India: The Sociology of Hinduism and Buddhism''==== | ||

| − | ''The Religion of India: The Sociology of | + | ''The Religion of India: The Sociology of Hinduism and Buddhism'' was Weber's third major work on the sociology of religion. In this work he dealt with the structure of [[India|Indian]] society, with the [[orthodox]] [[doctrine]]s of [[Hinduism]] and the [[heterodox]] doctrines of [[Buddhism]], with modifications brought by the influence of popular [[religiosity]], and finally with the impact of religious beliefs on the secular ethic of Indian society. |

| − | The Indian social system was shaped by the concept of [[caste]]. It directly linked religious belief and the segregation of society into [[status group]]s. Weber | + | The Indian social system was shaped by the concept of [[caste system|caste]]. It directly linked religious belief and the segregation of society into [[status group]]s. Weber described the caste system, consisting of the [[Brahmin]]s (priests), the [[Kshatriya]]s (warriors), the [[Vaisya]]s (merchants), the [[Sudra]]s (labourers), and the [[untouchables]]. |

| − | Weber | + | Weber paid special attention to Brahmins and analyzed why they occupied the highest place in Indian society for many centuries. With regard to the concept of [[dharma]] he concluded that the Indian ethical pluralism is very different both from the universal ethic of Confucianism and [[Christianity]]. He noted that the caste system prevented the development of urban status groups. |

| − | Next, Weber | + | Next, Weber analyzed Hindu religious beliefs, including [[asceticism]] and the Hindu world view, the Brahman orthodox doctrines, the rise and fall of Buddhism in India, the [[Hindu restoration]], and the evolution of the [[guru]]. He noted the idea of an immutable world order consisting of the eternal cycles of [[rebirth]] and the deprecation of the mundane world, and found that the traditional caste system, supported by the religion, slowed economic development. |

| − | He | + | He argued that it was the Messianic prophecies in the countries of the [[Near East]], as distinguished from the prophecy of the [[Asia]]tic mainland, that prevented the countries of the Occident from following the paths of development marked out by China and India, and his next work, ''Ancient Judaism'' was an attempt to prove this theory. |

====''Ancient Judaism''==== | ====''Ancient Judaism''==== | ||

| − | In ''Ancient | + | In ''Ancient Judaism'', his fourth major work on the sociology of religion, Weber attempted to explain the "combination of circumstances" that was responsible for the early differences between Oriental and Occidental religiosity. It is especially visible when the interworldly [[asceticism]] developed by Western Christianity is contrasted with mystical contemplation of the kind developed in India. Weber noted that some aspects of Christianity sought to conquer and change the world, rather than withdraw from its imperfections. This fundamental characteristic of Christianity (when compared to [[Far East|Far Eastern]] religions) stems originally from the ancient Jewish [[prophecy]]. |

| − | Stating his reasons for investigating ancient Judaism, Weber wrote that ''"Anyone who is heir to the traditions of modern European civilization will approach the problems of universal history with a set of questions, which to him appear both inevitable and legitimate. These questions will turn on the combination of circumstances which has brought about the cultural phenomena that are uniquely Western and that have at the same time (…) a universal cultural significance"''. | + | Stating his reasons for investigating ancient [[Judaism]], Weber wrote that ''"Anyone who is heir to the traditions of modern European civilization will approach the problems of universal history with a set of questions, which to him appear both inevitable and legitimate. These questions will turn on the combination of circumstances which has brought about the cultural phenomena that are uniquely Western and that have at the same time (…) a universal cultural significance"''. |

| − | Weber | + | Weber analyzed the interaction between the [[Bedouin]]s, the cities, the herdsmen and the peasants, including the conflicts between them and the rise and fall of the [[United Monarchy]]. The time of the United Monarchy appears as a mere episode, dividing the period of [[confederation|confederacy]] since the [[Exodus]] and the settlement of the [[Israelite]]s in [[Palestine (region)|Palestine]] from the period of political decline following the [[Division of the Monarchy]]. This division into periods has major implications for religious history. Since the basic tenets of Judaism were formulated during the time of Israelite confederacy and after the fall of the United Monarchy, they became the basis of the prophetic movement that left a lasting impression on the Western civilization. |

| − | Weber | + | Weber noted that Judaism not only fathered Christianity and Islam, but was crucial to the rise of modern Occident state, as its influence were as important to those of [[Hellenistic]] and [[Ancient Rome|Roman]] cultures. |

===Sociology of politics and government=== | ===Sociology of politics and government=== | ||

| − | In the sociology of politics and government, Weber's most significant essay is probably his '' | + | In the sociology of politics and government, Weber's most significant essay is probably his ''Politics as a Vocation''. Therein, Weber unveils the definition of the [[state]] that has become so pivotal to Western social thought: that the state is that entity which possesses a monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force, which it may elect to delegate as it sees fit. Politics is to be understood as any activity in which the state might engage itself in order to influence the relative distribution of force. A politician must not be a man of the "true [[Christian ethic]]", understood by Weber as being the ethic of the [[Sermon on the Mount]], that is to say, the injunction to turn the other cheek. An adherent of such an ethic ought rather to be understood to be a [[saint]], for it is only saints, according to Weber, that can appropriately follow it. The political realm is no realm for saints. A politician ought to marry the ethic of ultimate ends and the ethic of responsibility, and must possess both a passion for his avocation and the capacity to distance himself from the subject of his exertions (the governed). |

| − | Weber distinguished three pure types of political leadership, domination and authority: | + | Weber distinguished three pure types of political leadership, domination and authority: charismatic domination (familial and religious), traditional domination ([[patriarch]]s, [[patrimonalism]], [[feudalism]]), and legal domination (modern law and state, bureaucracy). In his view, every historical relation between rulers and ruled contained elements that can be analysed on the basis of this [[tripartite classification of authority|tripartite]] distinction. He also notes that the instability of charismatic authority inevitably forces it to "routinize" into a more structured form of authority. |

Many aspects of modern [[public administration]] are attributed to Weber. A classic, hierarchically organized [[civil service]] of the Continental type is called "Weberian civil service", although this is only one ideal type of public administration and government described in his ''[[magnum opus]]'' ''Economy and Society'' (1922). In this work, Weber outlines a famous description of rationalization (of which bureaucratization is a part) as a shift from a value-oriented organization and action (traditional authority and charismatic authority) to a goal-oriented organization and action (legal-rational authority). The result, according to Weber, is a "polar night of icy darkness", in which increasing rationalization of human life traps individuals in an "iron cage" of rule-based, rational control. | Many aspects of modern [[public administration]] are attributed to Weber. A classic, hierarchically organized [[civil service]] of the Continental type is called "Weberian civil service", although this is only one ideal type of public administration and government described in his ''[[magnum opus]]'' ''Economy and Society'' (1922). In this work, Weber outlines a famous description of rationalization (of which bureaucratization is a part) as a shift from a value-oriented organization and action (traditional authority and charismatic authority) to a goal-oriented organization and action (legal-rational authority). The result, according to Weber, is a "polar night of icy darkness", in which increasing rationalization of human life traps individuals in an "iron cage" of rule-based, rational control. | ||

| − | Weber's bureaucracy studies also led him to his accurate analysis that [[socialism]] in [[Russia]] would, due to the abolishing of the [[free market]] and its mechanisms, lead to over-bureaucratization (evident, for example, in the | + | Weber's bureaucracy studies also led him to his accurate analysis that [[socialism]] in [[Russia]] would, due to the abolishing of the [[free market]] and its mechanisms, lead to over-bureaucratization (evident, for example, in the shortage economy) rather than to the "withering away of the state" (as Karl Marx had predicted would happen in [[communism|communist]] society). |

===Economics=== | ===Economics=== | ||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

While Max Weber is best known and recognized today as one of the leading scholars and founders of modern sociology, he also accomplished much in the field of [[economics]]. However, during his life no such distinctions really existed. | While Max Weber is best known and recognized today as one of the leading scholars and founders of modern sociology, he also accomplished much in the field of [[economics]]. However, during his life no such distinctions really existed. | ||

| − | From the point of view of the economists, he is a representative of the "Youngest" [[German Historical School]]. His most valued contributions to the field of economics is his famous work, ''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism''. This seminal essay discusses the differences between religions and the relative wealth of their followers. Weber's work is parallel to | + | From the point of view of the economists, he is a representative of the "Youngest" [[German Historical School]]. His most valued contributions to the field of economics is his famous work, ''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism''. This seminal essay discusses the differences between religions and the relative wealth of their followers. Weber's work is parallel to Sombart's treatise of the same phenomenon, which, however, located the rise of Capitalism in Judaism. Weber's other main contributions to economics (as well as to social sciences in general) is his work on [[methodology]]: his theories of ''Verstehen'' (known as "understanding" or "interpretative sociology") and of antipositivism (known as "humanistic sociology"). |

| − | Max Weber formulated a three-component theory of stratification, with | + | Max Weber formulated a three-component theory of stratification, with "social class," "status class," and "party class" (or political class) as conceptually distinct elements. |

| − | * Social class is based on economically determined relationship to the [[market]] (owner, [[ | + | * Social class is based on economically determined relationship to the [[market]] (owner, [[rent|renter]], employee etc.). |

| − | * Status class is based on non- | + | * Status class is based on non-economic qualities like honor, prestige and religion. |

* Party class refers to affiliations in the political domain. | * Party class refers to affiliations in the political domain. | ||

All three dimensions have consequences for what Weber called "life chances". | All three dimensions have consequences for what Weber called "life chances". | ||

Revision as of 23:38, 3 December 2005

Maximilian Weber (April 21, 1864 – June 14, 1920) was a German political economist and sociologist who is considered one of the founders of the modern, "antipositivistic" study of sociology and public administration. His major works deal with rationalization in sociology of religion and government, but he also wrote much in the field of economics. His most recognized work is his essay The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, which began his work in the sociology of religion. Weber argued that religion was one of the primary reasons for the different ways the cultures of the Occident and the Orient have developed.

Life and career

Weber was born in Erfurt, Germany, the eldest of seven children of Max Weber Sr., a prominent politician and civil servant, and his wife Helene Fallenstein. His younger brother, Alfred, was also a sociologist and economist. Weber grew up in a household immersed in politics, and his father received a long list of prominent scholars and public figures in his salon. At the time, Weber proved to be intellectually precocious.

In 1882 Weber enrolled in the University of Heidelberg as a law student. Weber chose as his major study his father's field of law. Apart from his work in law, he attended lectures in economics and studied medieval history. In addition, Weber read a great deal in theology. In the fall of 1884 Weber returned to his parents' home to study at the University of Berlin. In 1886 Weber passed the examination for "Referendar", comparable to the bar examination in the American legal system. He earned his doctorate in law in 1889 by writing a doctoral dissertation on legal history entitled The History of Medieval Business Organisations.

In 1893 he married his distant cousin Marianne Schnitger, later a feminist and author in her own right, who after his death in 1920 was decisive in collecting and publishing Weber's works as books. In 1894 the couple moved to Freiburg, where Weber was appointed professor of economics at Freiburg University, before accepting the same position at the University of Heidelberg in 1897. The same year his father died two months after a severe quarrel with him. Following this incident Weber was more and more prone to "nervousness" and insomnia. He spent several months in a sanatorium in the summer and fall of 1900.

After his immense productivity in the early 1890s he finally resigned as a professor in the fall of 1903. In 1904 Max Weber began to publish some of his most seminal papers in this journal, notably his essay The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. It became his most famous work, and laid the foundations for his later research on the impact of cultures and religions on the development of economic systems.

In 1915 and 1916 he was a member of commisions that tried to retain German supremacy in Belgium and Poland after the war. Weber was a German imperialist and wanted to enlarge the German empire to the east and the west.

In 1918 Weber became a consultant to the German Armistice Commission at the Treaty of Versailles and to the commission charged with drafting the Weimar Constitution. He argued in favour of inserting Article 48 into the Weimar Constitution. This article was later used by Adolf Hitler to declare martial law and seize dictatorial powers.

From 1918, Weber resumed teaching, first at the University of Vienna, then in 1919 at the University of Munich. In Munich, he headed the first German University institute of sociology. Many colleagues and students in Munich despised him for his speeches and left wing attitude during the German revolution of 1918 and 1919. Right-wing students protested at his home.

Max Weber died of pneumonia in Munich on June 14, 1920.

Weber and German politics

Weber thought that the only way that German culture would survive was by creating an empire. He influenced German policy towards Eastern Germany. In 1894 he proposed closing the border to Polish workers from Russia and Austria-Hungary. However, in 1895, impressed by the attitude of the Russian liberal party, which wanted to change Russian nationalism by accepting ethnic minorities as Russians, he reversed his position.

Weber advocated democracy as a means for selecting strong leaders. He viewed democracy as a form of charisma where the "demagogue imposes his will on the masses." For this reason, the European left is highly critical of Weber for, albeit unwittingly, "preparing the intellectual groundwork for the leadership position of Adolf Hitler."

Weber was strongly anti-socialist, despising the anti-nationalist stance of the Marxist parties. He was surprised that the communists in Russia (who dissolved the old elite and bureaucracy) could survive for more than half a year.

Weber was very opposed to the conservatives who tried to hold back the democratic liberation of the working classes. Weber's personal and professional letters show considerable disgust for the anti-semitism of his day. It is doubtful that Weber would have supported the Nazis, had he lived long enough to see their activities.

Achievements

Max Weber was – along with Karl Marx, Vilfredo Pareto and Émile Durkheim – one of the founders of modern sociology. Whereas Pareto and Durkheim, following Comte, worked in the positivist tradition, Weber created and worked, like Werner Sombart, in the antipositivist, idealist and hermeneutic tradition. Those works started the antipositivistic revolution in social sciences, which stressed the difference between the social sciences and natural sciences, especially due to human social actions. Weber's early work was related to industrial sociology, but he is most famous for his later work on the sociology of religion and sociology of government.

Max Weber began his studies of Rationalization in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, in which he showed how the aims of certain Protestant denominations, particularly Calvinism, shifted towards the rational means of economic gain as a way of expressing that they had been blessed. The rational roots of this doctrine, he argued, soon grew incompatible with and larger than the religious, and so the latter were eventually discarded. Weber continued his investigation into this matter in later works, notably in his studies on bureaucracy and on the classifications of authority.

Theories

Sociology of religion

Weber's work on the sociology of religion started with the essay The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism and continued with the analysis of The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism, The Religion of India: The Sociology of Hinduism and Budhism, and Ancient Judaism.

His three main themes were the effect of religious ideas on economic activities, the relation between social stratification and religious ideas, and the distinguishable characteristics of Western civilization.

His goal was to find reasons for the different development paths of the cultures of the Occident and the Orient. In the analysis of his findings, Weber maintained that Puritan (and more widely, Protestant) religious ideas had had a major impact on the development of the economic system of Europe and the United States, but noted that they were not the only factors in this development. Weber identified "disenchantment of the world" as an important distinguishing aspect of Western culture.

The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

Weber's essay The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism is his most famous work. Here Weber puts forward the controversial thesis that the Protestant ethic influenced the development of capitalism. Religious devotion has usually been accompanied by rejection of wordly affairs, including economic pursuit. Why was that not the case with Protestantism? Weber addressed that paradox in his essay.

The answer was to be found in the religious ideas of the Reformation. Weber argued that certain Protestant ideas favored rational pursuit of economic gain and worldly activities which had been given positive spiritual and moral meaning. Particularly, Calvin's understanding of predestination, namely that sinful people cannot know directly whether they are part of God's elect to whom the grace of salvation is offered, was taken by Weber as the key to solving the paradox. He argued that the resultant insecurity on the part of Protestants, and their fear of eternal damnation, led them to seek signs indicating God's direction for their lives and affirmation of their correct behavior. Thus, hard work followed by financial success came to be the hallmark of God's grace. Coupled with traditional religious asceticism, these ideas encouraged people to accumulate wealth. It was not the goal of those religious ideas, but rather a byproduct – the inherent logic of those doctrines and the advice based upon them both directly and indirectly encouraged planning and self-denial in the pursuit of economic gain.

According to Weber, this "spirit of capitalism" not only involved hard work and entrepreneurism on the part of Protestants, but also a sense of stewardship over the resulting gains. For if money is not sought after for luxury or self-indulgence, but as moral affirmation, economizing and reinvesting in worthy enterprises become normal economic practices.

Weber acknowledged that other factors, both material and psychological, contributed to the development of modern capitalism. He also agreed that previous capitalist societies existed prior to Calvinism. However, in those cases religious views did not support the capitalist enterprise but rather limited it. Only the Protestant ethic, based on Calvinism, actively supported the accumulation of capital as a sign of God's grace.

The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism

The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism was Weber's second major work on the sociology of religion. Weber focused on those aspects of Chinese society that were different from those of Western Europe and especially contrasted with Puritanism, and posed a question why capitalism did not develop in China.

As in Europe, Chinese cities had been founded as forts or leaders' residences, and were the centers of trade and crafts. However, they never received political autonomy and its citizens had no special political rights or privileges. This is due to the strength of kinship ties, which stems from religious beliefs in ancestral spirits. Also, the guilds competed against each other for the favour of the Emperor, never uniting in order to fight for more rights. Therefore, the residents of Chinese cities never constituted a separate status class like the residents of European cities.

Weber emphasized that instead of metaphysical conjectures, Confucianism taught adjustment to the world. The "superior" man (literati) should stay away from the pursuit of wealth (though not from wealth itself). Therefore, becoming a civil servant was preferred to becoming a businessman and granted a much higher status.

Chinese civilization had no religious prophecy nor a powerful priestly class. The emperor was the high priest of the state religion and the supreme ruler, but popular cults were also tolerated (however the political ambitions of their priests were curtailed). This forms a sharp contrast with medieval Europe, where the Church curbed the power of secular rulers and the same faith was professed by rulers and common folk alike.

According to Weber, Confucianism and Puritanism represent two comprehensive but mutually exclusive types of rationalization, each attempting to order human life according to certain ultimate religious beliefs. However, Confucianism aimed at attaining and preserving "a cultured status position" and used as means adjustment to the world, education, self-perfection, politeness and familial piety.

The Religion of India: The Sociology of Hinduism and Buddhism

The Religion of India: The Sociology of Hinduism and Buddhism was Weber's third major work on the sociology of religion. In this work he dealt with the structure of Indian society, with the orthodox doctrines of Hinduism and the heterodox doctrines of Buddhism, with modifications brought by the influence of popular religiosity, and finally with the impact of religious beliefs on the secular ethic of Indian society.

The Indian social system was shaped by the concept of caste. It directly linked religious belief and the segregation of society into status groups. Weber described the caste system, consisting of the Brahmins (priests), the Kshatriyas (warriors), the Vaisyas (merchants), the Sudras (labourers), and the untouchables.

Weber paid special attention to Brahmins and analyzed why they occupied the highest place in Indian society for many centuries. With regard to the concept of dharma he concluded that the Indian ethical pluralism is very different both from the universal ethic of Confucianism and Christianity. He noted that the caste system prevented the development of urban status groups.

Next, Weber analyzed Hindu religious beliefs, including asceticism and the Hindu world view, the Brahman orthodox doctrines, the rise and fall of Buddhism in India, the Hindu restoration, and the evolution of the guru. He noted the idea of an immutable world order consisting of the eternal cycles of rebirth and the deprecation of the mundane world, and found that the traditional caste system, supported by the religion, slowed economic development.

He argued that it was the Messianic prophecies in the countries of the Near East, as distinguished from the prophecy of the Asiatic mainland, that prevented the countries of the Occident from following the paths of development marked out by China and India, and his next work, Ancient Judaism was an attempt to prove this theory.

Ancient Judaism

In Ancient Judaism, his fourth major work on the sociology of religion, Weber attempted to explain the "combination of circumstances" that was responsible for the early differences between Oriental and Occidental religiosity. It is especially visible when the interworldly asceticism developed by Western Christianity is contrasted with mystical contemplation of the kind developed in India. Weber noted that some aspects of Christianity sought to conquer and change the world, rather than withdraw from its imperfections. This fundamental characteristic of Christianity (when compared to Far Eastern religions) stems originally from the ancient Jewish prophecy.

Stating his reasons for investigating ancient Judaism, Weber wrote that "Anyone who is heir to the traditions of modern European civilization will approach the problems of universal history with a set of questions, which to him appear both inevitable and legitimate. These questions will turn on the combination of circumstances which has brought about the cultural phenomena that are uniquely Western and that have at the same time (…) a universal cultural significance".

Weber analyzed the interaction between the Bedouins, the cities, the herdsmen and the peasants, including the conflicts between them and the rise and fall of the United Monarchy. The time of the United Monarchy appears as a mere episode, dividing the period of confederacy since the Exodus and the settlement of the Israelites in Palestine from the period of political decline following the Division of the Monarchy. This division into periods has major implications for religious history. Since the basic tenets of Judaism were formulated during the time of Israelite confederacy and after the fall of the United Monarchy, they became the basis of the prophetic movement that left a lasting impression on the Western civilization.

Weber noted that Judaism not only fathered Christianity and Islam, but was crucial to the rise of modern Occident state, as its influence were as important to those of Hellenistic and Roman cultures.

Sociology of politics and government

In the sociology of politics and government, Weber's most significant essay is probably his Politics as a Vocation. Therein, Weber unveils the definition of the state that has become so pivotal to Western social thought: that the state is that entity which possesses a monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force, which it may elect to delegate as it sees fit. Politics is to be understood as any activity in which the state might engage itself in order to influence the relative distribution of force. A politician must not be a man of the "true Christian ethic", understood by Weber as being the ethic of the Sermon on the Mount, that is to say, the injunction to turn the other cheek. An adherent of such an ethic ought rather to be understood to be a saint, for it is only saints, according to Weber, that can appropriately follow it. The political realm is no realm for saints. A politician ought to marry the ethic of ultimate ends and the ethic of responsibility, and must possess both a passion for his avocation and the capacity to distance himself from the subject of his exertions (the governed).

Weber distinguished three pure types of political leadership, domination and authority: charismatic domination (familial and religious), traditional domination (patriarchs, patrimonalism, feudalism), and legal domination (modern law and state, bureaucracy). In his view, every historical relation between rulers and ruled contained elements that can be analysed on the basis of this tripartite distinction. He also notes that the instability of charismatic authority inevitably forces it to "routinize" into a more structured form of authority.

Many aspects of modern public administration are attributed to Weber. A classic, hierarchically organized civil service of the Continental type is called "Weberian civil service", although this is only one ideal type of public administration and government described in his magnum opus Economy and Society (1922). In this work, Weber outlines a famous description of rationalization (of which bureaucratization is a part) as a shift from a value-oriented organization and action (traditional authority and charismatic authority) to a goal-oriented organization and action (legal-rational authority). The result, according to Weber, is a "polar night of icy darkness", in which increasing rationalization of human life traps individuals in an "iron cage" of rule-based, rational control.

Weber's bureaucracy studies also led him to his accurate analysis that socialism in Russia would, due to the abolishing of the free market and its mechanisms, lead to over-bureaucratization (evident, for example, in the shortage economy) rather than to the "withering away of the state" (as Karl Marx had predicted would happen in communist society).

Economics

While Max Weber is best known and recognized today as one of the leading scholars and founders of modern sociology, he also accomplished much in the field of economics. However, during his life no such distinctions really existed.

From the point of view of the economists, he is a representative of the "Youngest" German Historical School. His most valued contributions to the field of economics is his famous work, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. This seminal essay discusses the differences between religions and the relative wealth of their followers. Weber's work is parallel to Sombart's treatise of the same phenomenon, which, however, located the rise of Capitalism in Judaism. Weber's other main contributions to economics (as well as to social sciences in general) is his work on methodology: his theories of Verstehen (known as "understanding" or "interpretative sociology") and of antipositivism (known as "humanistic sociology").

Max Weber formulated a three-component theory of stratification, with "social class," "status class," and "party class" (or political class) as conceptually distinct elements.

- Social class is based on economically determined relationship to the market (owner, renter, employee etc.).

- Status class is based on non-economic qualities like honor, prestige and religion.

- Party class refers to affiliations in the political domain.

All three dimensions have consequences for what Weber called "life chances".

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gesamtausgabe (generally critical, collected works edition), which is published by Mohr Siebeck in Tübingen, Germany.

- Reinhard Bendix (1960). Max Weber: An Intellectual Portrait. Doubleday.

- Dirk Kaesler (1989). Max Weber: An Introduction to His Life and Work. University of Chicago Press.

- Wolfgang Mommsen (1974). Max Weber und die Deutsche Politik 1890-1920. J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck)

- Guenther Roth (2001). Max Webers deutsch-englische Familiengeschichte. J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck)

- Marianne Weber (1929/1988). Max Weber: A Biography. New Brunswick: Transaction Books.

- Richard Swedberg, "Max Weber as an Economist and as a Sociologist", American Journal of Economics and Sociology

External links

Texts of Weber works:

- The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

- Large collection of the German original texts

- Large collection of English translations

- Another collection of English translations

- Yet another collection of English translations

- English translations of many of Weber's works

About Weber:

- Biography entry and link section

- Weber on Ideal Types

- Max Weber - The person

- More of Weber on Ideal Types

- An essay on Max Weber's View of Objectivity in Social Science

- Max Weber: On Bureaucracy

- Max Weber: On Capitalism As above, but on capitalism

- Some of Weber concepts in the form of a list

- Max Weber's HomePage "A site for undergraduates"

Images:

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.