Mammary gland

Mammary glands are the organs in female mammals that produce and secrete milk for the nourishment of newborn mammalian offspring. These exocrine glands are enlarged and modified sweat glands, and are characteristic of the mammalia class which gave the mammary glands their name. Because of its unique developmental aspects and complex regulation by hormones and growth factors, the mammary gland has been especially important for scientists and researchers.

Structure

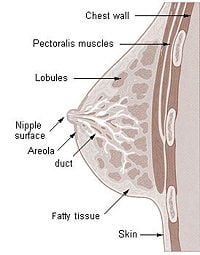

The basic components of the mammary gland are the alveoli (hollow cavities, a few millimetres large) lined with milk-secreting epithelial cells and surrounded by myoepithelial cells. These alveoli join up to form groups known as lobules, and each lobule has a lactiferous duct that drains into openings in the nipple. The myoepithelial cells can contract, similar to muscle cells, and thereby push the milk from the alveoli through the lactiferous ducts towards the nipple, where it collects in widenings (sinuses) of the ducts. A suckling baby essentially squeezes the milk out of these sinuses.

One distinguishes between a simple mammary gland, which consists of all the milk-secreting tissue leading to a single lactiferous duct, and a complex mammary gland, which consists of all the simple mammary glands serving one nipple.

Humans normally have two complex mammary glands, one in each breast, and each complex mammary gland consists of 10-20 simple glands. (The presence of more than two nipples is known as polythelia and the presence of more than two complex mammary glands as polymastia.)

Function

The function of the mammary glands in female breasts is to nurture the young by producing milk, which is secreted by the nipples during lactation. However, zoologists point out that no female mammal other than the human has breasts of comparable size when not lactating and that humans are the only primate that have permanently swollen breasts. This suggests that the external form of the breasts is connected to factors other than lactation alone. The mammary glands that secrete the milk from the breasts actually make up a relatively small fraction of the overall breast tissue, and it is commonly assumed by biologists that the breasts serve as a secondary sex characteristics involved in attraction. Others believe that the human breast evolved in order to prevent infants from suffocating while feeding[1]. Since human infants do not have a protruding jaw like other primates, the infant's nose might be blocked by a flat female chest while feeding. According to this theory, as the human jaw became recessed, so the breasts became larger to compensate.

While the mammary glands that produce milk are present in the male, they normally remain undeveloped.

Development and hormonal control

The development of mammary glands is controlled by hormones. The mammary glands exist in both sexes, but they are rudimentary until puberty when in response to ovarian hormones, they begin to develop in the female. Estrogen promotes formation, while testosterone inhibits it.

At the time of birth, the baby has lactiferous ducts but no alveoli. Little branching occurs before puberty when ovarian estrogens stimulate branching differentiation of the ducts into spherical masses of cells that will become alveoli. True secretory alveoli only develop in pregnancy, where rising levels of estrogen and progesterone cause further branching and differentiation of the duct cells, together with an increase in adipose tissue and a richer blood flow.

Colostrum is secreted in late pregnancy and for the first few days after giving birth. True milk secretion (lactation) begins a few days later due to a reduction in circulating progesterone and the presence of the hormone prolactin. The suckling of the baby causes the release of the hormone oxytocin which stimulates contraction of the myoepithelial cells.

Breast cancer

As described above, the cells of mammary glands can easily be induced to grow and multiply by hormones. If this growth runs out of control, cancer results. Almost all instances of breast cancer originate in the lobules or ducts of the mammary glands.

Other mammals

The number of complex and simple mammary glands varies widely in different mammals. The nipples and glands can occur anywhere along the two milk lines, two roughly-parallel lines along the front of the body. They are easy to visualize on dogs or cats, where there are from 3 to 5 pairs of nipples following the milk lines. In general most mammals develop mammary glands in pairs along these lines, with a number approximating the number of young typically birthed at a time.

Male mammals typically have rudimentary mammary glands and nipples, with a few exceptions: male rats and mice don't have nipples, and male horses lack nipples and mammary glands.

Mammary glands are true protein factories, and several companies have constructed transgenic animals, mainly goats and cows, in order to produce proteins for pharmaceutical use. Complex glycoproteins such as monoclonal antibodies or antithrombin cannot be produced by genetically engineered bacteria, and the production in live mammals is much cheaper than the use of mammalian cell cultures.

Mammary tumor

A mammary tumor is a tumor originating in the mammary gland. It is a common finding in older female dogs and cats that are not spayed, but they are found in other animals as well. The mammary glands in dogs and cats are associated with their nipples and extend from the underside of the chest to the groin on both sides of the midline. There are many differences between mammary tumors in animals and breast cancer in humans, including tumor type, malignancy, and treatment options.

Female dogs who are not spayed or who are spayed later than the first heat cycle are more likely to develop mammary tumors. Specifically, dogs not spayed or spayed after the age of two years are seven times more likely to develop mammary tumors than dogs spayed by six months old.[1] The tumors are often multiple. They are most commonly seen between the ages of eight and ten years old.[1]

About 50 percent of mammary tumors in dogs are malignant.[2] Malignant mammary tumors are divided into sarcomas, carcinosarcomas, inflammatory carcinomas (usually anaplastic carcinomas), and carcinomas (including adenocarcinomas), which are the most common.[2] Adenomas and fibroadenomas make up the benign types.

Intact cats are seven times more likely to develop mammary tumors than cats spayed between the ages of six and twelve months.[1] Siamese cats seem to have increased risk.[2] Malignant tumors make up 90 percent of mammary tumors in cats, almost all adenocarcinomas.[1] Like in dogs, tumor size is an important prognostic factor.

Mammary tumors are rare in ferrets. Appearance tends to be a soft, dark colored lump. Most seem to be benign and occur most frequently in neutered males. Surgery is recommended.

Mammary tumors in guinea pigs occur in males and females. Most are benign, but 30 percent are adenocarcinomas.[3]

Most mammary tumors in mice are adenocarcinomas. They can be caused by viral infection.[3] Recurrence rates are high, and therefore there is a poor prognosis.

Most mammary tumors in rats are benign fibroadenomas. Less than 10 percent are adenocarcinomas.[3] They occur in male and female rats. The tumors can be large and occur anywhere on the trunk. There is a good prognosis with surgery. Spayed rats have a decreased risk of developing mammary tumors.

Mammary tumors tend to be benign in hamsters and malignant in gerbils.

External links

- Comparative Mammary Gland Anatomy by W. L. Hurley

- On the anatomy of the breast by Sir Astley Paston Cooper (1840). Numerous drawings, in the public domain.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Morrison, Wallace B. (1998). Cancer in Dogs and Cats, 1st ed., Williams and Wilkins. ISBN 0683061054.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Ettinger, Stephen J.;Feldman, Edward C. (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 4th ed., W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 0721667953.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hillyer, Elizabeth V.;Quesenberry, Katherin E. (1997). Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents: Clinical Medicine and Surgery, 1st ed., W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 0721640230.