Difference between revisions of "Liturgical music" - New World Encyclopedia

Dave Eaton (talk | contribs) |

Dave Eaton (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

Prior to the [[Second Vatican Council]], according to the [[Motu proprio]] of Pius X (22 Nov. 1903), the following were the general guiding principles of the Church: "Sacred music should possess, in the highest degree, the qualities proper to the liturgy, or more precisely, sanctity and purity of form from which its other character of universality spontaneously springs. It must be holy, and must therefore exclude all profanity, not only from itself but also from the manner in which it is presented by those who execute it. It must be true art, for otherwise it cannot exercise on the minds of the hearers that influence which the Church meditates when she welcomes into her liturgy the art of music. But it must also be universal, in the sense that, while every nation is permitted to admit into its ecclesiastical compositions those special forms which may be said to constitute its native music, still these forms must be subordinated in such a manner to the general characteristics of sacred music, that no one of any nation may receive an impression other than good on hearing them." This was explanded upon by Pope [[Pius XII]] in his [[Motu Proprio]] title [http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/pius_xii/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xii_enc_25121955_musicae-sacrae_en.html Musicae Sacrae] | Prior to the [[Second Vatican Council]], according to the [[Motu proprio]] of Pius X (22 Nov. 1903), the following were the general guiding principles of the Church: "Sacred music should possess, in the highest degree, the qualities proper to the liturgy, or more precisely, sanctity and purity of form from which its other character of universality spontaneously springs. It must be holy, and must therefore exclude all profanity, not only from itself but also from the manner in which it is presented by those who execute it. It must be true art, for otherwise it cannot exercise on the minds of the hearers that influence which the Church meditates when she welcomes into her liturgy the art of music. But it must also be universal, in the sense that, while every nation is permitted to admit into its ecclesiastical compositions those special forms which may be said to constitute its native music, still these forms must be subordinated in such a manner to the general characteristics of sacred music, that no one of any nation may receive an impression other than good on hearing them." This was explanded upon by Pope [[Pius XII]] in his [[Motu Proprio]] title [http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/pius_xii/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xii_enc_25121955_musicae-sacrae_en.html Musicae Sacrae] | ||

| − | With advent [[Protestant]]ism there was a significant emphasis on using [[music]] in liturgical contexts. For musicians such as [[Martin Luther]] and [[Johann Sebastian Bach]], [[music]] was not primarily an exercise in compositional technique but rathe possessed deep spiritual and religious underpinnings | + | With advent [[Protestant]]ism there was a significant emphasis on using [[music]] in liturgical contexts. For musicians such as [[Martin Luther]] and [[Johann Sebastian Bach]], [[music]] was not primarily an exercise in compositional technique but rathe possessed deep spiritual and religious underpinnings. |

| − | Although he introduced no new musical forms, Bach expanded and enriched the prevailing German style with extraordinary contrapuntal technique, a seemingly effortless control of harmonic and motivic organization from the smallest to the largest scales, and the adaptation of rhythms and textures from abroad, particularly from [[Italy]] and [[France]]. Revered for their intellectual depth, technical command and artistic beauty, his works include many liturgical works such as the Mass in B Minor, the St. Matthew Passion and about 240 church cantatas. | + | Although he introduced no new musical forms, Bach expanded and enriched the prevailing German style with extraordinary contrapuntal technique, a seemingly effortless control of harmonic and motivic organization from the smallest to the largest scales, and the adaptation of rhythms and textures from abroad, particularly from [[Italy]] and [[France]]. Revered for their intellectual depth, technical command and artistic beauty, his works include many liturgical works such as the Mass in B Minor, the St. Matthew Passion and about 240 church cantatas which he often composed for specific religious occasions such as Christmas and Easter. |

==Modern Jewish liturgical music== | ==Modern Jewish liturgical music== | ||

Revision as of 21:02, 16 June 2008

Liturgical music is a form of music originating as a part of religious ceremony. It includes a number of traditions, both ancient and modern. Liturgical music is best known as a part of Catholic Mass, the Anglican Holy Communion service, the Lutheran mass, the Orthodox liturgy and other Christian services including the Divine Office. Such ceremonial music in the Judeo-Christian tradition can be traced back to both Temple and synagogue worship of the Hebrews.

The qualities that create the distinctive character of liturgical music are rooted in the music's conception and composition according to the norms and needs of the various historic liturgies of particular denominations. Although it is most common to attribute the term to Western and Judeo-Christian traditions, music accompanying religious rituals can be traced back to ancient cultures such and Chinese and Indian as well.

For composers of the Baroque period, the composition of music was not primarily an exercise in compositional interplay, but rather possessed deep spiritual and religious underpinnings. Johann Sebastien Bach stated, "The sole and end aim of figured-bass should be nothing else than God's glory and the recreation of the mind. Where this object is not kept in view, there can be no true music, but only infernal scraping and bawling." Bach was influenced greatly by Martin Luther's assertion that music was, "a gift from God, not a human gift" and "a sermon in sound."

Jewish Origins

david — I added some text here... cut or add as you wish... Dan

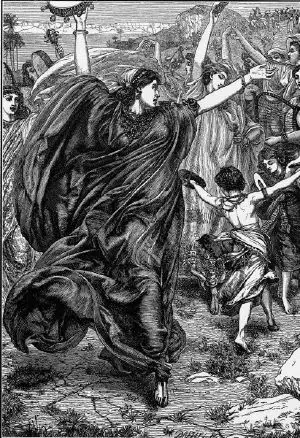

Sacred singing in Hebrew tradition dates back to songs of Miriam and Moses, reportedly sung when the Israelites crossed the Red Sea. King David was traditionally believed to have written most of the biblical psalms. However, scholars believe that many of them were composed by priests substantially later and designed of to be sung in the Temple in Jerusalem.

The psalms covered a wide variety of genres, from prayers of supplication, to mourning, triumphal marches, and enthronement hymns. Many were songs of joyful praise, as typified by Psalm 98: "Make a joyful noise unto the Lord, all the earth: make a loud noise, and rejoice, and sing praise."

Biblical and Talmudic sources mention the following instruments that were used in the ancient Temple:

- the Nevel, a 12-stringed harp;

- the Kinnor, a lyre with 10 strings;

- the Shofar, a hollowed-out ram's horn;

- the chatzutzera, or trumpet, made of silver;

- the tof or small drum;

- the metziltayim, or cymbal;

- the paamon or bell;

- the halil or big flute.

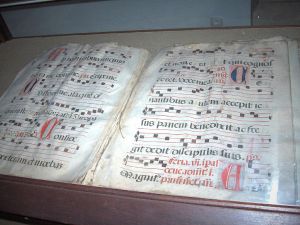

According to the Mishna, the regular Temple orchestra consisted of twelve instruments, and the choir of twelve male singers. The earliest synagogal music was based on the system reportedly used in the Temple.

After the destruction of the Temple and the subsequent diaspora of the Jewish people, a consensus developed that all music and singing would be banned. This was codified as a rule by the early Jewish rabbinic authorities. However, the ban on singing and music soon became understood as applying only outside of religious services. Within the synagogue, the custom of singing soon re-emerged. In later years, the practice evolved to allow singing for feasts celebrating religious life-cycle events such as weddings, and over time the formal ban against singing and performing music lost its force altogether.

Jewish liturgical music began to crystallize into definite form with the piyyutim (liturgical poems) many of which show an interplay with Islamic influences resulting from the Jewish diaspora in Muslim lands. The cantor sang the melodies selected by their writer or by himself, thus introducing fixed melodies into synagogal music. Cantors also continued to recite traditional prayers, which were chanted more than sung. In moments of inspiration a cantor would sometimes give utterance to a phrase of unusual beauty, which would occasionally find its way into the congregational tradition and be passed on to succeeding generations.

Genesis in Christian Tradition

With the decline of Rome and the ascendancy of Christianity in Europe during the third and fourth centuries, the seeds that would blossom into the great art of the Western world were planted deeply into the fertile soil of religious faith and practice. Arnold Toynbee's assessment that the Christian church was "the chrysalis out of which our Western society emerged," attests to the role that Christian thought played in the development of Western musical theory, aesthetics and axiology.

The early church was a small, vulnerable group with one of its missions being to convert pagan Europe. It thus endeavored to resist any influence by the surrounding pagan cultures. Early Christians felt this to be absolutely crucial to their mission and deemed it necessary to subordinate all earthy things, including music, to the ultimate goal of protecting the eternal condition of one’s soul.

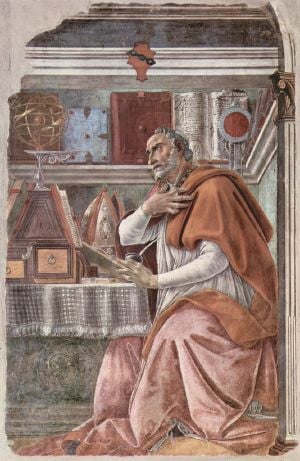

The Greek philosophy, which came to the early Christian church via Rome, that music was a medium that had connections to the forces of nature and possessed the power to affect human thought and conduct, was assimilated into early church culture and reiterated in the writings of several Christian philosophers, most notably Boethius (ca. A.D. 480-524) and St. Augustine (A.D. 354-430). Boethius' treatise De Institutione musica stood as an authoritative source of understanding for writers of Medieval times with regards to harmonization the physical world (musica mundana), the mind and body (musica humana) and tones/music (musica instrumentalis).

The evolution of music and its integration into liturgical practice throughout the Middle Ages gave rise to new attitudes about music and its purpose and function; most notably the idea that music was to be the "servant" of religion. For the Church elders of the Middle Ages, music was deemed good only when it "opens the mind to Christian teachings and disposes the soul to holy thoughts." The church in the Middle Ages was highly concerned with the potentially corrupting elements of music and as a result certain factions within Church hierarchy that felt art in general, and music in particular, was inimical to religion.

Yet the aesthetic beauty of music could not be denied. The medieval Christian concept that spiritual fulfillment and redemption was somehow hindered or obstructed by pleasurable things such as music is one that troubled even the most enlightened practitioners of the faith. Consider St. Augustine's observations on this dilemma:

"When I call to mind the tears I shed at the songs of my church....I then acknowledge the great utility of this custom. Thus vacillate I between dangerous pleasure and tried soundness; being inclined rather to approve of the use of singing in the church, that so by delights the ear the weaker minds may be stimulated to a devotional frame. Yet when it happens to me to be more moved by the singing than by what is sung, I confess myself to have sinned criminally, and then would rather not have heard the singing."

As music historian Daniel J. Grout points out, there is music in every Age that is not suitable for religious or devotional purposes and we should not be too quick to condemn the Church for its seemingly narrow and "timorous distrust of the sensual and emotional qualities of music." The Christian church, like the ancient cultures of Ages past, was merely making a distinction between sacred and secular art which it thought necessary to the process of inculcating its early converts with an ascetic principle that could endure and survive any corrupting influences.

As mentioned previously, it was thought that instrumental music could not illicit the spirit of divinity as well as vocal music, therefore instrumental music was for the most part excluded in liturgical services in the early church. This preference for vocal music was a significant factor as to why Gregorian Chant and plainsong became the predominant mediums for liturgical music for hundreds of years.

Liturgical Music in Christianity

needs to proceed historically, include non catholic traditions

The interest taken by the Catholic Church in music is shown not only by practitioners, but also by numerous enactments and regulations calculated to foster music worthy of Divine service. Contemporary official church policy is expressed most particularly in the document Sacrosanctum Concilium (items 112-121) of the Second Vatican Council.

While there have been historic disputes within the church where elaborate music has been under criticism, there are many period works by Orlandus de Lassus, Allegri, Vittoria, where the most elaborate means of expression are employed in liturgical music, but which, nevertheless, conform to every liturgical requirement while seeming to be spontaneous outpourings of adoring hearts (cf. contrapuntal or polyphonic music). Besides plain chant and the polyphonic style, the Catholic Church also permits homophonic or figured compositions with or without instrumental accompaniment, written either in in ecclesiastical modes, or the modern major or minor keys. Gregorian chant is warmly recommended by the Catholic Church, as both polyphonic music and modern unison music for the assembly.

Prior to the Second Vatican Council, according to the Motu proprio of Pius X (22 Nov. 1903), the following were the general guiding principles of the Church: "Sacred music should possess, in the highest degree, the qualities proper to the liturgy, or more precisely, sanctity and purity of form from which its other character of universality spontaneously springs. It must be holy, and must therefore exclude all profanity, not only from itself but also from the manner in which it is presented by those who execute it. It must be true art, for otherwise it cannot exercise on the minds of the hearers that influence which the Church meditates when she welcomes into her liturgy the art of music. But it must also be universal, in the sense that, while every nation is permitted to admit into its ecclesiastical compositions those special forms which may be said to constitute its native music, still these forms must be subordinated in such a manner to the general characteristics of sacred music, that no one of any nation may receive an impression other than good on hearing them." This was explanded upon by Pope Pius XII in his Motu Proprio title Musicae Sacrae

With advent Protestantism there was a significant emphasis on using music in liturgical contexts. For musicians such as Martin Luther and Johann Sebastian Bach, music was not primarily an exercise in compositional technique but rathe possessed deep spiritual and religious underpinnings.

Although he introduced no new musical forms, Bach expanded and enriched the prevailing German style with extraordinary contrapuntal technique, a seemingly effortless control of harmonic and motivic organization from the smallest to the largest scales, and the adaptation of rhythms and textures from abroad, particularly from Italy and France. Revered for their intellectual depth, technical command and artistic beauty, his works include many liturgical works such as the Mass in B Minor, the St. Matthew Passion and about 240 church cantatas which he often composed for specific religious occasions such as Christmas and Easter.

Modern Jewish liturgical music

this needs to focus musical aspect, more on cantor's role etc

Jewish services (Hebrew: תפלה, tefillah ; plural תפלות, tefillot ; Yinglish: davening) are the prayer recitations which form part of the observance of Judaism. These prayers, often with instructions and commentary, are found in the siddur, the traditional Jewish prayer book.

Traditionally, three prayers are recited daily, with additional prayers on the Sabbath and most Jewish holidays. A distinction is made between individual prayer and communal prayer in a minyan (quorum). Communal prayer is generally preferable, as it includes components that cannot be performed without a quorum.

Most of the Jewish liturgy is sung or chanted with traditional melody or trope (nigun). Depending upon the size and platform, many synagogues designate or employ a professional or lay hazzan (cantor) for the purpose of leading the congregation in prayer.

Daven is the originally exclusively Eastern Yiddish verb meaning "pray"; it is widely used by Ashkenazic Orthodox Jews. In Yinglish, this has become the Anglicised davening. The origin of the word is obscure, but is thought by some to have come from Middle French and by others to be derived from a Slavic word meaning "give". Others claim that it originates from an Aramaic word, "de'avoohon", meaning "of our forefathers", as the three prayers were invented by Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (Talmud). Still others connect it with the Latinate "divine." In Western Yiddish, the term for "pray" is oren, a word with clear roots in Romance languages — compare Spanish and Portuguese orar and Latin orare.

Non-western sacred music

a sentence or two on each, maybe more on Islamic music

Contemporary liturgical music

could be moved up and combine with Christian tradition

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Curtis, Gareth, Fifteenth-century liturgical music. 4, Early masses and mass-pairs, London: British Academy by Stainer and Bell, 2001. ISBN 0-852-49846-2

- Leaver, Robin A., Luther's liturgical music: principles and implications, Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 2007. ISBN 0-802-83221-0

- Montone, Brian, Liturgical music after Vatican II: a misinterpretation, CA: Mills College, 2006. OCLC 74282553

- Gaines, James R., "Evening in the Palace of Reason," Harper/Collins, New York, 2005, ISBN 0-00-715658-8

- Donald J. Grout: A History of Western Music, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. New York, 1960

External Links

- Anglican church music Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- Antiochian Orthodox liturgical music Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- Carpatho Rusyn Liturgical Music Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- Catholic liturgical music at St Meinrad's Monastery Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- Jewish liturgical music Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- Latter Day Saint church music Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- The Church Music Association of America Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- Pope Benedict XVI on liturgical music Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- The Royal School of Church Music Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- Syriac church music Retrieved September 16, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.