Difference between revisions of "Literacy" - New World Encyclopedia

(Started) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (43 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}} |

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Education]] | [[Category:Education]] | ||

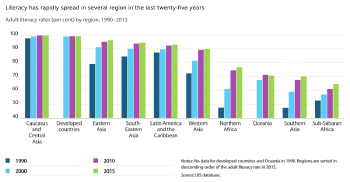

| + | [[File:Figure 5 Literacy has rapidly spread Reading the past writing the future.png|right|350px|thumb|Literacy rapidly spread in several regions from 1990-2015]] | ||

| + | '''Literacy''' is usually defined as the ability to [[Reading|read]] and [[writing|write]], or the ability to use [[language]] to read, write, [[Listening|listen]], and [[Speech|speak]]. In modern contexts, the word refers to reading and writing at a level adequate for [[communication]], or at a level that lets one understand and communicate ideas in a literate [[society]], so as to take part in that society. Literacy can also refer to proficiency in a number of fields, such as [[art]] or physical activity. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Literacy rates are a crucial measure of a region's [[human capital]]. This is because literate people can be trained less expensively than illiterate people, generally have a higher socio-economic status, and enjoy better health and employment prospects. Literacy is part of the development of individual maturity, allowing one to attain one's potential as a person, and an essential skill that allows one to be a fully functioning member of society able to contribute one's abilities and talents for the good of all. Thus, one of the [[Millennium Development Goals]] of the [[United Nations]] is to achieve universal [[primary education]], a level of schooling that includes basic literacy and numeracy, thus ensuring that all people throughout the world are able to participate in society in a fuller way. | ||

| + | ==Definitions of literacy== | ||

| + | Traditional definitions of literacy consider the ability to "read, write, spell, listen, and speak."<ref> L.C. Moats, ''Speech to Print: Language Essentials for Teachers'' (Paul H. Brookes Co., 2000, ISBN 1557663874).</ref> | ||

| + | The standards for what constitutes "literacy" vary, depending on social, cultural, and political context. For example, a basic literacy standard in many societies is the ability to read the [[newspaper]]. Increasingly, many societies require literacy with [[computer]]s and other digital technologies. | ||

| − | [[ | + | Being literate is highly correlated with [[wealth]], but it is important not to conflate the two. Increases in literacy do not necessarily cause increases in wealth, nor does greater wealth necessarily improve literacy. |

| − | |||

| − | + | Some have argued that the definition of literacy should be expanded. For example, in the United States, the [[National Council of Teachers of English]] and the [[International Reading Association]] have added "visually representing" to the traditional list of competencies. Similarly, Literacy Advance offers the following definition: | |

| + | <blockquote>Literacy is the ability to read, write, speak and listen, and use numeracy and technology, at a level that enables people to express and understand ideas and opinions, to make decisions and solve problems, to achieve their goals, and to participate fully in their community and in wider society. Achieving literacy is a lifelong learning process. | ||

| + | <ref> [https://www.literacyadvance.org/About_Us/Defining_Literacy/ Defining Literacy] Literacy Advance. Retrieved May 11, 2019.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Along these lines, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization ([[UNESCO]]) has defined literacy as the "ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts. Literacy involves a continuum of learning in enabling individuals to achieve their goals, to develop their knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in their community and wider society."<ref>UNESCO, [http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001362/136246e.pdf The Plurality of Literacy and its implications for Policies and Programs] Education Sector Position Paper, 2004. Retrieved May 11, 2019.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Other ideas about expanding literacy are described below. | |

| + | |||

| + | ===Information and communication technology literacy=== | ||

| + | Since the [[computer]] and the [[Internet]] developed in the 1990s, some have asserted that the definition of literacy should include the ability to use and communicate in a diverse range of technologies. Modern [[technology]] requires mastery of new tools, such as [[internet browser]]s, word processing programs, and [[text message]]s. This has given rise to an interest in a new dimension of communication called [[multimedia literacy]].<ref>Gunther Kress, ''Literacy in the New Media Age'' (London: Routledge, 2003, ISBN 0415253551).</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | For example, Doug Achterman has said: | ||

| + | <blockquote>Some of the most exciting research happens when students collaborate to pool their research and analyze their data, forming a kind of understanding that would be difficult for an individual student to achieve.<ref>Doug Achterman, "Beyond Wikipedia: Using Wikis to Connect Students and Teachers to the Research Process and to One Another" ''Teacher Librarian'', 34(2), 19-22 (2006, December).</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Art as a form of literacy=== | ||

| + | Some schools in the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada, as well as Finland and the U.S. have become "arts-based" or "arts integrated" schools. These schools teach students to communicate using any form humans use to express or receive thoughts and feelings. [[Music]], visual [[art]], [[drama]]/[[theater]], and [[dance]] are mainstays for [[teaching]] and [[learning]] in these schools. The Kennedy Center Partners in Education, headquartered in Washington, DC, is one organization whose mission is to train teachers to use an expanded view of literacy which includes the [[fine arts]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Postmodernist concepts of literacy=== | ||

| + | Some scholars argue that literacy is not autonomous or a set of discrete technical and objective skills that can be applied across context. Instead, they posit that literacy is determined by the [[culture|cultural]], [[politics|political]], and [[history|historical]] contexts of the community in which it is used, drawing on academic disciplines including [[cultural anthropology]] and [[linguistic anthropology]] to make the case.<ref>Michele Knobel, ''Everyday Literacies: Students, Discourse, and Social Practice'' (New York: Lang, 1999, ISBN 0820439703). </ref> In the view of these thinkers, definitions of literacy are based on [[ideology|ideologies]]. New literacies such as [[critical literacy]], [[media literacy]], [[technacy]], [[visual literacy]], [[computer literacy]], [[multimedia literacy]], [[information literacy]], [[health literacy]], and [[digital literacy]] are all examples of new literacies that are being introduced in contemporary literacy studies and media studies.<ref>C. Zarcadoolas, A. Pleasant, and D. Greer, ''Advancing Health Literacy: A Framework for Understanding and Action'' (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2006, ISBN 0787984337).</ref> | ||

== Literacy throughout history == | == Literacy throughout history == | ||

| − | + | The history of literacy goes back several thousand years, but before the [[industrial revolution]] finally made cheap [[paper]] and cheap [[book]]s available to all classes in industrialized countries in the mid-nineteenth century, only a small percentage of the population in these countries were literate. Up until that point, materials associated with literacy were prohibitively expensive for people other than wealthy individuals and institutions. For example, in England in 1841, 33 percent of men and 44 percent of women signed [[marriage]] certificates with their "mark," as they were unable to write a complete signature. Only in 1870 was government-financed public education made available in England. | |

| − | |||

| − | The history of literacy goes back several thousand years, but before the [[industrial revolution]] finally made cheap paper and cheap | ||

| − | What constitutes literacy has changed throughout history. | + | What constitutes literacy has changed throughout history. At one time, a literate person was one who could sign his or her name. At other points, literacy was measured only by the ability to read and write [[Latin]] (regardless of a person's ability to read or write his or her vernacular), or by the ability to read the [[Bible]]. The [[benefit of clergy]] in [[common law]] systems became dependent on reading a particular passage. |

| − | Literacy has also been used as a way to sort populations and control who has access to power. Because literacy permits learning and communication that oral and sign language alone cannot, illiteracy has been enforced in some places as a way of preventing unrest or revolution. During the Civil War era in the United States, white citizens in many areas banned teaching slaves to read or write presumably understanding the power of literacy. In the years following the Civil War, the ability to read and write was used to determine whether one had the right to vote. This effectively served to prevent former slaves from joining the electorate and maintained the status quo. | + | Literacy has also been used as a way to sort populations and control who has access to power. Because literacy permits [[learning]] and [[communication]] that oral and sign language alone cannot, illiteracy has been enforced in some places as a way of preventing unrest or revolution. During the [[American Civil War|Civil War]] era in the United States, white citizens in many areas banned teaching [[slavery|slaves]] to read or write presumably understanding the power of literacy. In the years following the Civil War, the ability to read and write was used to determine whether one had the right to vote. This effectively served to prevent former slaves from joining the electorate and maintained the status quo. In 1964, educator [[Paulo Freire]] was arrested, expelled, and [[exile]]d from his native [[Brazil]] because of his work in teaching Brazilian [[peasant]]s to read. |

| − | From another perspective, the historian [[Harvey Graff]] has argued that the introduction of mass | + | From another perspective, the historian [[Harvey Graff]] has argued that the introduction of mass [[school]]ing was in part an effort to control the type of literacy that the working class had access to. That is, literacy learning was increasing outside of formal settings (such as schools) and this uncontrolled, potentially critical reading could lead to increased radicalization of the populace. Mass schooling was meant to temper and control literacy, not spread it. |

| − | + | The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization ([[UNESCO]]) projected worldwide literacy rates until 2015. This organization argues that rates will decline steadily through this time due to higher birth rates among the [[poverty|impoverished]], mostly in developing countries who do not have access to schools or the time to devote to studies. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | === Examples of highly literate cultures in the past=== |

| − | + | [[India]] and [[China]] were advanced in literacy in early times and made many scientific advancements. | |

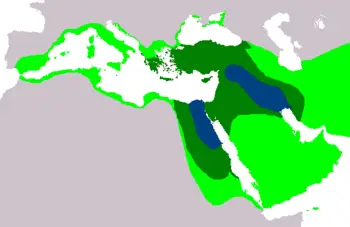

| − | [[Image:Literacy.PNG|thumb|350px|The slow spread of literacy in the ancient world. The dark blue areas were literate at around | + | [[Image:Literacy.PNG|thumb|350px|The slow spread of literacy in the ancient world. The dark blue areas were literate at around 2300 B.C.E. The dark green areas were literate at around 1300 B.C.E. The light green areas were literate at around 300 B.C.E. Note that other Asian societies were literate at these times, but they are not included on this map. Note also that even in the colored regions, functional literacy was usually restricted to a handful of ruling elite.]] |

The large amount of [[graffiti]] found at [[Ancient Rome|Roman]] sites such as [[Pompeii]], shows that at least a large minority of the population would have been literate. | The large amount of [[graffiti]] found at [[Ancient Rome|Roman]] sites such as [[Pompeii]], shows that at least a large minority of the population would have been literate. | ||

| − | Because of its emphasis on the individual reading of the [[Qur'an]] in the original [[Arabic alphabet]] many [[ | + | Because of its emphasis on the individual reading of the [[Qur'an]] in the original [[Arabic alphabet]] many [[Islam]]ic countries have known a comparatively high level of literacy during most of the past twelve centuries. In Islamic edict (or [[Fatwa]]), to be literate is an individual religious obligation. |

| − | In the Middle Ages, literacy rates among [[Jew]]s in Europe were much higher than in the surrounding Christian populations. | + | In the [[Middle Ages]], literacy rates among [[Jew]]s in [[Europe]] were much higher than in the surrounding [[Christian]] populations. Most Jewish males at least learned to read and write [[Hebrew]]. Judaism places great importance on the study of holy texts, the [[Tanakh]] and the [[Talmud]]. |

| − | In [[New England]], the literacy rate was over 50 percent during the first half of the | + | In [[New England]], the literacy rate was over 50 percent during the first half of the seventeenth century, and it rose to 70 percent by 1710. By the time of the [[American Revolution]], it was around 90 percent. This is seen by some as a [[Unintended consequence|side effect]] of the [[Puritan]] belief in the importance of [[Bible]] reading. |

| − | In [[Wales]], the literacy rate rocketed during the | + | In [[Wales]], the literacy rate rocketed during the eighteenth century, when [[Griffith Jones (Llanddowror)|Griffith Jones]] ran a system of circulating schools, with the aim of enabling everyone to read the Bible (in Welsh). It is claimed that in 1750, Wales had the highest literacy rate of any country in the world. |

| − | Historically, the literacy rate has also been high in the [[Lutheran]] countries of [[Northern Europe]]. The 1686 church law ''(kyrkolagen)'' of the Kingdom of [[Sweden]] (which at the time included all of modern Sweden, [[Finland]], and [[Estonia]]) enforced literacy on the people and a hundred years later, by the end of the | + | Historically, the literacy rate has also been high in the [[Lutheran]] countries of [[Northern Europe]]. The 1686 church law ''(kyrkolagen)'' of the Kingdom of [[Sweden]] (which at the time included all of modern Sweden, [[Finland]], and [[Estonia]]) enforced literacy on the people and a hundred years later, by the end of the eighteenth century, the literacy rate was close to 100 percent. Even before the 1686 law, literacy was widespread in Sweden. However, the ability to read did not automatically imply ability to write, and as late as the nineteenth century many Swedes, especially women, could not write. This proves even more difficult, because many literary historians measure literacy rates based on the ability that people had to sign their own names.<ref>Children of the Code, [http://www.childrenofthecode.org/Tour/c5/viral.htm Online Video: The Spread, Rise and Fall of Early Literacy.] Retrieved May 11, 2019.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | [http://www.childrenofthecode.org/Tour/c5/viral.htm Online Video: The Spread, Rise and Fall of Early Literacy] | ||

== Teaching literacy == | == Teaching literacy == | ||

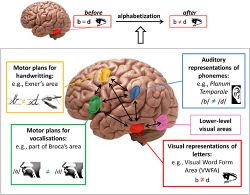

| − | Literacy comprises a number of | + | [[File:Brain pathways for mirror discrimination learning during literacy acquisition.jpg|thumb|250px|Brain pathways for mirror discrimination learning during literacy acquisition. Upper: The Visual Word Form Area [VWFA] (in red) presents mirror invariance before alphabetization and mirror discrimination for letters after alphabetization.]] |

| + | Literacy comprises a number of sub-skills, including [[phonological awareness]], [[phonics|decoding]], [[fluency]], [[comprehension]], and [[vocabulary]]. Mastering each of these sub-skills is necessary for students to become proficient readers. | ||

===Alphabetic principle and English orthography=== | ===Alphabetic principle and English orthography=== | ||

| − | Beginning readers must understand the concept of the ''alphabetic principle'' in order to master basic reading skills. | + | Beginning readers must understand the concept of the ''alphabetic principle'' in order to master basic reading skills. A writing system is said to be ''alphabetic'' if it uses [[symbol]]s to represent individual language sounds. In contrast, [[logograph]]ic writing systems such as [[Written Chinese|Chinese]]) use a symbol to represent an entire [[word]], and syllabic writing systems (such as [[Japan]]ese [[kana]]) use a symbol to represent a single [[syllable]]. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Alphabetic writing systems vary in complexity. For example, Spanish is an alphabetic writing system that has a nearly perfect one-to-one correspondence of symbols to individual sounds. In Spanish, most of the time, words are spelled the way they sound, that is, word spellings are almost always regular. English, on the other hand, is far more complex in that it does not have a one-to-one correspondence between symbols and sounds. English has individual sounds that can be represented by more than one symbol or symbol combination. For example, the long |a| sound can be represented by a-consonant-e as in ate, -ay as in hay, -ea as in steak, -ey as in they, -ai as in pain, and -ei as in vein. In addition, there are many words with irregular spelling and many [[homophone]]s (words that sound the same but have different meanings and often different spellings as well). Pollack Pickeraz asserted that there are 45 phonemes in the English language, and that the 26 letters of the English alphabet can represent the 45 phonemes in about 350 ways. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Clearly, the complexity of English [[orthography]] makes it more difficult for children to learn decoding and encoding rules, and more difficult for teachers to teach them. However, effective word recognition relies on the basic understanding that letters represent the sounds of spoken language, that is, word recognition relies on the reader's understanding of the alphabetic principle. | |

| − | + | ===Phonics=== | |

| + | [[Phonics]] is an instructional technique that teaches readers to attend to the letters or groups of letters that make up words. So, to read the word ''throat'' using phonics, each [[grapheme]] (a letter or letters that represent one sound) is examined separately: ''Th'' says /θ/, ''r'' says /ɹ/, ''oa'' says /oʊ/, and ''t'' says /t/. There are various methods for teaching phonics. A common way to teach this is to have the novice reader pronounce each individual sound and "blend" them to pronounce the whole word. This is called synthetic phonics. | ||

| − | + | ===Whole language=== | |

| + | Because English spelling has so many irregularities and exceptions, advocates of [[whole language]] recommend that novice readers should learn a little about the individual letters in words, especially the consonants and the "short vowels." Teachers provide this knowledge opportunistically, in the context of stories that feature many instances of a particular letter. This is known as "embedded phonics." Children use their letter-sound knowledge in combination with context to read new and difficult words.<ref>Gail Tompkins, ''Literacy for the 21st Century'' (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2006, ISBN 1428819460).</ref> | ||

| − | + | ===Why learning to read is difficult=== | |

| − | + | Many children of average and above average intelligence experience difficulty when learning to read. According to Grover Whitehurst, Assistant Secretary, U.S. Department of Education, learning to read is difficult for several reasons. First, reading requires the mastery of a code that maps human speech sounds to written symbols, and this code is not readily apparent or easy to understand. Second, reading is not a natural process; it was invented by humans fairly recently in their development. The human brain is wired for spoken language, but it is not wired to process the code of written language. Third, confusion can be introduced at the time of instruction by teachers who do not understand what the code is or how it needs to be taught.<ref>Grover Whitehurst, [http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/whitehurst.htm Children of the Code interview.] Retrieved May 11, 2019. </ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Illiteracy== | ==Illiteracy== | ||

| − | Illiteracy is the condition of not being able to read or write. | + | Illiteracy is the condition of not being able to read or write. Functional illiteracy refers to the inability of an individual to use [[reading]], [[writing]], and [[computational]] skills efficiently in everyday life situations. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Functional illiteracy=== |

| + | Unlike an illiterate, one who is functionally illiterate is able to read and write text in his/her native language. However, he/she does so with a variable degree of [[grammar|grammatical]] correctness, and style, and cannot perform fundamental tasks such as: Filling out an employment application, following written instructions, reading a [[newspaper]] article, reading traffic signs, consulting a [[dictionary]], or understanding a [[bus]] schedule. In short, when confronted with printed materials, adults without basic literacy skills cannot function effectively in modern society. Functional illiteracy also severely limits interaction with [[information and communication technologies]] (using a [[personal computer]] to work with a [[word processor]], a [[web browser]], a [[spreadsheet]] application, or using a [[mobile phone]] efficiently). | ||

| − | + | Those who are functionally illiterate may be subject to social intimidation, [[health]] risks, [[stress]], low income, and other pitfalls associated with their inability. | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| + | The correlation between [[crime]] and functional illiteracy is well-known to [[criminology|criminologists]] and [[sociology|sociologists]] throughout the world. In the early 2000s, it was estimated that 60 percent of adults in federal and state [[prison]]s in the [[United States]] were functionally or marginally illiterate, and 85 percent of [[juvenile delinquency|juvenile offenders]] had problems associated with reading, writing, and basic mathematics.<ref>BeginToRead, [http://www.begintoread.com/research/literacystatistics.html Literacy Statistics] Retrieved May 11, 2019.</ref> | ||

| + | A ''Literacy at Work'' study, published by the Northeast Institute in 2001, found that [[business]] losses attributed to basic skill deficiencies run into billions of dollars a year due to low productivity, errors, and accidents attributed to functional illiteracy. | ||

| + | [[Sociology|Sociological]] research has demonstrated that countries with lower levels of functional illiteracy among their adult populations tend to be those with the highest levels of scientific literacy among the lower stratum of young people nearing the end of their formal academic studies. This correspondence suggests that a contributing factor to a society's level of civic literacy is the capacity of schools to assure the students attaining the functional literacy required to comprehend the basic texts and documents associated with competent citizenship.<ref>Henry Milner, ''Civic Literacy: How Informed Citizens Make Democracy Work'' (Tufts, 2002, ISBN 978-1584651734).</ref> | ||

| + | ==Efforts to improve literacy rates== | ||

| + | {{readout||right|250px|One of the [[United Nations]] Millennium Development Goals was to achieve universal [[primary education]], a level of schooling that includes basic literacy and numeracy}} | ||

| + | It is generally accepted that literacy brings benefits to individuals, communities, and nations. Individuals have a sense of personal accomplishment, feelings of social belonging as they can better understand the world around them, and more access to employment. Communities gain greater integration and nations improve their output and place in global standings. As such, many organizations and governments are devoted to improving literacy rates around the world. The largest of these is the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). UNESCO tracks education statistics around the world, develops strategies for providing access to education, develops lessons and guides, and releases international standards. One of the Millennium Development Goals of the [[United Nations]] was to achieve universal [[primary education]], a level of schooling that includes basic literacy and numeracy by the year 2015. Although not achieving 100 percent success, the United Nations reported that "Among youth aged 15 to 24, the literacy rate has improved globally from 83 per cent to 91 per cent between 1990 and 2015, and the gap between women and men has narrowed."<ref>United Nations, [http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/education.shtml Millennium Development Goals and Beyond 2015.] Retrieved May 11, 2019.</ref> | ||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

| − | |||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| + | * Biller, Peter. ''Heresy and Literacy, 1000-1530.'' Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0521575761 | ||

| + | * Bowman, Alan. ''Literacy and Power in the Ancient World.'' Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 0521587360 | ||

| + | * Clanchy, M.T. ''From Memory to Written Record: England 1066-1307.'' Blackwell Publishing, 1993. ISBN 0631168575 | ||

| + | * Hirsch, E.D., Joseph F. Kett, and James Trefil. ''The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know.'' Houghton Mifflin, 2002. ISBN 0618226478 | ||

| + | * Hobart, Michael. ''Information Ages: Literacy, Numeracy, and the Computer Revolution.'' Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000. ISBN 0801864127 | ||

| + | * Hoggart, Richard. ''The Uses of Literacy.'' Transaction Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0765804212 | ||

| + | * Knobel, Michele. ''Everyday Literacies: Students, Discourse, and Social Practice''. New York: Lang, 1999. ISBN 0820439703 | ||

| + | * Kress, Gunther. ''Literacy in the New Media Age''. London: Routledge, 2003. ISBN 0415253551 | ||

| + | * Milner, Henry. ''Civic Literacy: How Informed Citizens Make Democracy Work''. Tufts, 2002. ISBN 978-1584651734 | ||

| + | * Moats, L.C. ''Speech to Print: Language Essentials for Teachers''. Paul H. Brookes Co., 2000. ISBN 1557663874 | ||

| + | * Pinnell, Gay. ''The Continuum of Literacy Learning, Grades K-8: Behaviors and Understandings to Notice, Teach, and Support.'' Heinemann, 2007. ISBN 0325012393 | ||

| + | * Prothero, Stephen. ''Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know—And Doesn't.'' HarperOne, 2007. ISBN 0060846704 | ||

| + | * Rubinger, Richard. ''Popular Literacy in Early Modern Japan.'' University of Hawaii Press, 2007. ISBN 0824830261 | ||

| + | * Stock, Brian. ''The Implications of Literacy.'' Princeton University Press, 1987. ISBN 0691102279 | ||

| + | * Thomas, Rosalind. ''Literacy and Orality in Ancient Greece.'' Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 0521377420 | ||

| + | * Tompkins, Gail. ''Literacy for the 21st Century''. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2009. ISBN 978-0135028926 | ||

| + | * Tompkins, Gail. ''50 Literacy Strategies: Step-by-Step.'' Prentice Hall, 2008. ISBN 0135158168 | ||

| + | * Zarcadoolas, Christina, Andrew Pleasant, and David Greer. ''Advancing Health Literacy: A Framework for Understanding and Action''. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. ISBN 0787984337 | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved October 29, 2022. | |

| − | + | * [https://www.nala.ie/literacy Literacy in Ireland] National Adult Literacy Agency. | |

| − | * [ | + | * [http://nces.ed.gov/NAAL/ National Center for Education Statistics] Literacy statistics for the United States. |

| − | * [http://nces.ed.gov/NAAL/ National Center for Education Statistics] Literacy statistics for the United States | + | * [http://lincs.ed.gov/ Literacy Information and Communication System (LINCS)]—initiative of the U.S. Department of Education to support adult literacy |

| − | + | * [http://www.unesco.org/education/literacy United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Literacy Portal]. | |

| − | * [http:// | + | * [http://proliteracy.org/ Proliteracy Worldwide]. |

| − | + | * [https://www.literacyworldwide.org/ International Literacy Association]. | |

| − | + | * [http://www.literacytrust.org.uk/ National Literacy Trust (UK)] (NLT) - registered charity. | |

| − | + | * [http://www.fcrr.org/ Florida Center for Reading Research]. | |

| − | * [http://www.unesco.org/education/literacy United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Literacy Portal] | ||

| − | * [http://proliteracy.org/ Proliteracy Worldwide | ||

| − | |||

| − | * [ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * [http://www.literacytrust.org.uk/ National Literacy Trust (UK)] (NLT) - registered charity. | ||

| − | * [http://www.fcrr.org/ Florida Center for Reading Research] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credits|Literacy|156097875|Functional_illiteracy|156171709|}} | {{Credits|Literacy|156097875|Functional_illiteracy|156171709|}} | ||

Latest revision as of 04:28, 29 October 2022

Literacy is usually defined as the ability to read and write, or the ability to use language to read, write, listen, and speak. In modern contexts, the word refers to reading and writing at a level adequate for communication, or at a level that lets one understand and communicate ideas in a literate society, so as to take part in that society. Literacy can also refer to proficiency in a number of fields, such as art or physical activity.

Literacy rates are a crucial measure of a region's human capital. This is because literate people can be trained less expensively than illiterate people, generally have a higher socio-economic status, and enjoy better health and employment prospects. Literacy is part of the development of individual maturity, allowing one to attain one's potential as a person, and an essential skill that allows one to be a fully functioning member of society able to contribute one's abilities and talents for the good of all. Thus, one of the Millennium Development Goals of the United Nations is to achieve universal primary education, a level of schooling that includes basic literacy and numeracy, thus ensuring that all people throughout the world are able to participate in society in a fuller way.

Definitions of literacy

Traditional definitions of literacy consider the ability to "read, write, spell, listen, and speak."[1]

The standards for what constitutes "literacy" vary, depending on social, cultural, and political context. For example, a basic literacy standard in many societies is the ability to read the newspaper. Increasingly, many societies require literacy with computers and other digital technologies.

Being literate is highly correlated with wealth, but it is important not to conflate the two. Increases in literacy do not necessarily cause increases in wealth, nor does greater wealth necessarily improve literacy.

Some have argued that the definition of literacy should be expanded. For example, in the United States, the National Council of Teachers of English and the International Reading Association have added "visually representing" to the traditional list of competencies. Similarly, Literacy Advance offers the following definition:

Literacy is the ability to read, write, speak and listen, and use numeracy and technology, at a level that enables people to express and understand ideas and opinions, to make decisions and solve problems, to achieve their goals, and to participate fully in their community and in wider society. Achieving literacy is a lifelong learning process. [2]

Along these lines, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has defined literacy as the "ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts. Literacy involves a continuum of learning in enabling individuals to achieve their goals, to develop their knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in their community and wider society."[3]

Other ideas about expanding literacy are described below.

Information and communication technology literacy

Since the computer and the Internet developed in the 1990s, some have asserted that the definition of literacy should include the ability to use and communicate in a diverse range of technologies. Modern technology requires mastery of new tools, such as internet browsers, word processing programs, and text messages. This has given rise to an interest in a new dimension of communication called multimedia literacy.[4]

For example, Doug Achterman has said:

Some of the most exciting research happens when students collaborate to pool their research and analyze their data, forming a kind of understanding that would be difficult for an individual student to achieve.[5]

Art as a form of literacy

Some schools in the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada, as well as Finland and the U.S. have become "arts-based" or "arts integrated" schools. These schools teach students to communicate using any form humans use to express or receive thoughts and feelings. Music, visual art, drama/theater, and dance are mainstays for teaching and learning in these schools. The Kennedy Center Partners in Education, headquartered in Washington, DC, is one organization whose mission is to train teachers to use an expanded view of literacy which includes the fine arts.

Postmodernist concepts of literacy

Some scholars argue that literacy is not autonomous or a set of discrete technical and objective skills that can be applied across context. Instead, they posit that literacy is determined by the cultural, political, and historical contexts of the community in which it is used, drawing on academic disciplines including cultural anthropology and linguistic anthropology to make the case.[6] In the view of these thinkers, definitions of literacy are based on ideologies. New literacies such as critical literacy, media literacy, technacy, visual literacy, computer literacy, multimedia literacy, information literacy, health literacy, and digital literacy are all examples of new literacies that are being introduced in contemporary literacy studies and media studies.[7]

Literacy throughout history

The history of literacy goes back several thousand years, but before the industrial revolution finally made cheap paper and cheap books available to all classes in industrialized countries in the mid-nineteenth century, only a small percentage of the population in these countries were literate. Up until that point, materials associated with literacy were prohibitively expensive for people other than wealthy individuals and institutions. For example, in England in 1841, 33 percent of men and 44 percent of women signed marriage certificates with their "mark," as they were unable to write a complete signature. Only in 1870 was government-financed public education made available in England.

What constitutes literacy has changed throughout history. At one time, a literate person was one who could sign his or her name. At other points, literacy was measured only by the ability to read and write Latin (regardless of a person's ability to read or write his or her vernacular), or by the ability to read the Bible. The benefit of clergy in common law systems became dependent on reading a particular passage.

Literacy has also been used as a way to sort populations and control who has access to power. Because literacy permits learning and communication that oral and sign language alone cannot, illiteracy has been enforced in some places as a way of preventing unrest or revolution. During the Civil War era in the United States, white citizens in many areas banned teaching slaves to read or write presumably understanding the power of literacy. In the years following the Civil War, the ability to read and write was used to determine whether one had the right to vote. This effectively served to prevent former slaves from joining the electorate and maintained the status quo. In 1964, educator Paulo Freire was arrested, expelled, and exiled from his native Brazil because of his work in teaching Brazilian peasants to read.

From another perspective, the historian Harvey Graff has argued that the introduction of mass schooling was in part an effort to control the type of literacy that the working class had access to. That is, literacy learning was increasing outside of formal settings (such as schools) and this uncontrolled, potentially critical reading could lead to increased radicalization of the populace. Mass schooling was meant to temper and control literacy, not spread it.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) projected worldwide literacy rates until 2015. This organization argues that rates will decline steadily through this time due to higher birth rates among the impoverished, mostly in developing countries who do not have access to schools or the time to devote to studies.

Examples of highly literate cultures in the past

India and China were advanced in literacy in early times and made many scientific advancements.

The large amount of graffiti found at Roman sites such as Pompeii, shows that at least a large minority of the population would have been literate.

Because of its emphasis on the individual reading of the Qur'an in the original Arabic alphabet many Islamic countries have known a comparatively high level of literacy during most of the past twelve centuries. In Islamic edict (or Fatwa), to be literate is an individual religious obligation.

In the Middle Ages, literacy rates among Jews in Europe were much higher than in the surrounding Christian populations. Most Jewish males at least learned to read and write Hebrew. Judaism places great importance on the study of holy texts, the Tanakh and the Talmud.

In New England, the literacy rate was over 50 percent during the first half of the seventeenth century, and it rose to 70 percent by 1710. By the time of the American Revolution, it was around 90 percent. This is seen by some as a side effect of the Puritan belief in the importance of Bible reading.

In Wales, the literacy rate rocketed during the eighteenth century, when Griffith Jones ran a system of circulating schools, with the aim of enabling everyone to read the Bible (in Welsh). It is claimed that in 1750, Wales had the highest literacy rate of any country in the world.

Historically, the literacy rate has also been high in the Lutheran countries of Northern Europe. The 1686 church law (kyrkolagen) of the Kingdom of Sweden (which at the time included all of modern Sweden, Finland, and Estonia) enforced literacy on the people and a hundred years later, by the end of the eighteenth century, the literacy rate was close to 100 percent. Even before the 1686 law, literacy was widespread in Sweden. However, the ability to read did not automatically imply ability to write, and as late as the nineteenth century many Swedes, especially women, could not write. This proves even more difficult, because many literary historians measure literacy rates based on the ability that people had to sign their own names.[8]

Teaching literacy

Literacy comprises a number of sub-skills, including phonological awareness, decoding, fluency, comprehension, and vocabulary. Mastering each of these sub-skills is necessary for students to become proficient readers.

Alphabetic principle and English orthography

Beginning readers must understand the concept of the alphabetic principle in order to master basic reading skills. A writing system is said to be alphabetic if it uses symbols to represent individual language sounds. In contrast, logographic writing systems such as Chinese) use a symbol to represent an entire word, and syllabic writing systems (such as Japanese kana) use a symbol to represent a single syllable.

Alphabetic writing systems vary in complexity. For example, Spanish is an alphabetic writing system that has a nearly perfect one-to-one correspondence of symbols to individual sounds. In Spanish, most of the time, words are spelled the way they sound, that is, word spellings are almost always regular. English, on the other hand, is far more complex in that it does not have a one-to-one correspondence between symbols and sounds. English has individual sounds that can be represented by more than one symbol or symbol combination. For example, the long |a| sound can be represented by a-consonant-e as in ate, -ay as in hay, -ea as in steak, -ey as in they, -ai as in pain, and -ei as in vein. In addition, there are many words with irregular spelling and many homophones (words that sound the same but have different meanings and often different spellings as well). Pollack Pickeraz asserted that there are 45 phonemes in the English language, and that the 26 letters of the English alphabet can represent the 45 phonemes in about 350 ways.

Clearly, the complexity of English orthography makes it more difficult for children to learn decoding and encoding rules, and more difficult for teachers to teach them. However, effective word recognition relies on the basic understanding that letters represent the sounds of spoken language, that is, word recognition relies on the reader's understanding of the alphabetic principle.

Phonics

Phonics is an instructional technique that teaches readers to attend to the letters or groups of letters that make up words. So, to read the word throat using phonics, each grapheme (a letter or letters that represent one sound) is examined separately: Th says /θ/, r says /ɹ/, oa says /oʊ/, and t says /t/. There are various methods for teaching phonics. A common way to teach this is to have the novice reader pronounce each individual sound and "blend" them to pronounce the whole word. This is called synthetic phonics.

Whole language

Because English spelling has so many irregularities and exceptions, advocates of whole language recommend that novice readers should learn a little about the individual letters in words, especially the consonants and the "short vowels." Teachers provide this knowledge opportunistically, in the context of stories that feature many instances of a particular letter. This is known as "embedded phonics." Children use their letter-sound knowledge in combination with context to read new and difficult words.[9]

Why learning to read is difficult

Many children of average and above average intelligence experience difficulty when learning to read. According to Grover Whitehurst, Assistant Secretary, U.S. Department of Education, learning to read is difficult for several reasons. First, reading requires the mastery of a code that maps human speech sounds to written symbols, and this code is not readily apparent or easy to understand. Second, reading is not a natural process; it was invented by humans fairly recently in their development. The human brain is wired for spoken language, but it is not wired to process the code of written language. Third, confusion can be introduced at the time of instruction by teachers who do not understand what the code is or how it needs to be taught.[10]

Illiteracy

Illiteracy is the condition of not being able to read or write. Functional illiteracy refers to the inability of an individual to use reading, writing, and computational skills efficiently in everyday life situations.

Functional illiteracy

Unlike an illiterate, one who is functionally illiterate is able to read and write text in his/her native language. However, he/she does so with a variable degree of grammatical correctness, and style, and cannot perform fundamental tasks such as: Filling out an employment application, following written instructions, reading a newspaper article, reading traffic signs, consulting a dictionary, or understanding a bus schedule. In short, when confronted with printed materials, adults without basic literacy skills cannot function effectively in modern society. Functional illiteracy also severely limits interaction with information and communication technologies (using a personal computer to work with a word processor, a web browser, a spreadsheet application, or using a mobile phone efficiently).

Those who are functionally illiterate may be subject to social intimidation, health risks, stress, low income, and other pitfalls associated with their inability.

The correlation between crime and functional illiteracy is well-known to criminologists and sociologists throughout the world. In the early 2000s, it was estimated that 60 percent of adults in federal and state prisons in the United States were functionally or marginally illiterate, and 85 percent of juvenile offenders had problems associated with reading, writing, and basic mathematics.[11]

A Literacy at Work study, published by the Northeast Institute in 2001, found that business losses attributed to basic skill deficiencies run into billions of dollars a year due to low productivity, errors, and accidents attributed to functional illiteracy.

Sociological research has demonstrated that countries with lower levels of functional illiteracy among their adult populations tend to be those with the highest levels of scientific literacy among the lower stratum of young people nearing the end of their formal academic studies. This correspondence suggests that a contributing factor to a society's level of civic literacy is the capacity of schools to assure the students attaining the functional literacy required to comprehend the basic texts and documents associated with competent citizenship.[12]

Efforts to improve literacy rates

It is generally accepted that literacy brings benefits to individuals, communities, and nations. Individuals have a sense of personal accomplishment, feelings of social belonging as they can better understand the world around them, and more access to employment. Communities gain greater integration and nations improve their output and place in global standings. As such, many organizations and governments are devoted to improving literacy rates around the world. The largest of these is the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). UNESCO tracks education statistics around the world, develops strategies for providing access to education, develops lessons and guides, and releases international standards. One of the Millennium Development Goals of the United Nations was to achieve universal primary education, a level of schooling that includes basic literacy and numeracy by the year 2015. Although not achieving 100 percent success, the United Nations reported that "Among youth aged 15 to 24, the literacy rate has improved globally from 83 per cent to 91 per cent between 1990 and 2015, and the gap between women and men has narrowed."[13]

Notes

- ↑ L.C. Moats, Speech to Print: Language Essentials for Teachers (Paul H. Brookes Co., 2000, ISBN 1557663874).

- ↑ Defining Literacy Literacy Advance. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ↑ UNESCO, The Plurality of Literacy and its implications for Policies and Programs Education Sector Position Paper, 2004. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ↑ Gunther Kress, Literacy in the New Media Age (London: Routledge, 2003, ISBN 0415253551).

- ↑ Doug Achterman, "Beyond Wikipedia: Using Wikis to Connect Students and Teachers to the Research Process and to One Another" Teacher Librarian, 34(2), 19-22 (2006, December).

- ↑ Michele Knobel, Everyday Literacies: Students, Discourse, and Social Practice (New York: Lang, 1999, ISBN 0820439703).

- ↑ C. Zarcadoolas, A. Pleasant, and D. Greer, Advancing Health Literacy: A Framework for Understanding and Action (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2006, ISBN 0787984337).

- ↑ Children of the Code, Online Video: The Spread, Rise and Fall of Early Literacy. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ↑ Gail Tompkins, Literacy for the 21st Century (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2006, ISBN 1428819460).

- ↑ Grover Whitehurst, Children of the Code interview. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ↑ BeginToRead, Literacy Statistics Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ↑ Henry Milner, Civic Literacy: How Informed Citizens Make Democracy Work (Tufts, 2002, ISBN 978-1584651734).

- ↑ United Nations, Millennium Development Goals and Beyond 2015. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Biller, Peter. Heresy and Literacy, 1000-1530. Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0521575761

- Bowman, Alan. Literacy and Power in the Ancient World. Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 0521587360

- Clanchy, M.T. From Memory to Written Record: England 1066-1307. Blackwell Publishing, 1993. ISBN 0631168575

- Hirsch, E.D., Joseph F. Kett, and James Trefil. The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know. Houghton Mifflin, 2002. ISBN 0618226478

- Hobart, Michael. Information Ages: Literacy, Numeracy, and the Computer Revolution. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000. ISBN 0801864127

- Hoggart, Richard. The Uses of Literacy. Transaction Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0765804212

- Knobel, Michele. Everyday Literacies: Students, Discourse, and Social Practice. New York: Lang, 1999. ISBN 0820439703

- Kress, Gunther. Literacy in the New Media Age. London: Routledge, 2003. ISBN 0415253551

- Milner, Henry. Civic Literacy: How Informed Citizens Make Democracy Work. Tufts, 2002. ISBN 978-1584651734

- Moats, L.C. Speech to Print: Language Essentials for Teachers. Paul H. Brookes Co., 2000. ISBN 1557663874

- Pinnell, Gay. The Continuum of Literacy Learning, Grades K-8: Behaviors and Understandings to Notice, Teach, and Support. Heinemann, 2007. ISBN 0325012393

- Prothero, Stephen. Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know—And Doesn't. HarperOne, 2007. ISBN 0060846704

- Rubinger, Richard. Popular Literacy in Early Modern Japan. University of Hawaii Press, 2007. ISBN 0824830261

- Stock, Brian. The Implications of Literacy. Princeton University Press, 1987. ISBN 0691102279

- Thomas, Rosalind. Literacy and Orality in Ancient Greece. Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 0521377420

- Tompkins, Gail. Literacy for the 21st Century. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2009. ISBN 978-0135028926

- Tompkins, Gail. 50 Literacy Strategies: Step-by-Step. Prentice Hall, 2008. ISBN 0135158168

- Zarcadoolas, Christina, Andrew Pleasant, and David Greer. Advancing Health Literacy: A Framework for Understanding and Action. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. ISBN 0787984337

External links

All links retrieved October 29, 2022.

- Literacy in Ireland National Adult Literacy Agency.

- National Center for Education Statistics Literacy statistics for the United States.

- Literacy Information and Communication System (LINCS)—initiative of the U.S. Department of Education to support adult literacy

- United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Literacy Portal.

- Proliteracy Worldwide.

- International Literacy Association.

- National Literacy Trust (UK) (NLT) - registered charity.

- Florida Center for Reading Research.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.