Ancient Ksour of Ouadane, Chinguetti, Tichitt and Oualata

Mary Anglin (talk | contribs) (→Tichit) |

Mary Anglin (talk | contribs) m (→References) |

||

| Line 127: | Line 127: | ||

*''Archnet''. [http://archnet.org/library/sites/one-site.tcl?site_id=7728 Great Mosque of Chinguetti] Retrieved December 18, 2008. | *''Archnet''. [http://archnet.org/library/sites/one-site.tcl?site_id=7728 Great Mosque of Chinguetti] Retrieved December 18, 2008. | ||

*Canagasabey, Rohan. March 22, 2006. [http://www.themorningleader.lk/20060322/life.html Ksours — Mauritania’s ancient towns of Sahara] ''Leader Publications''. Retrieved December 18, 2008. | *Canagasabey, Rohan. March 22, 2006. [http://www.themorningleader.lk/20060322/life.html Ksours — Mauritania’s ancient towns of Sahara] ''Leader Publications''. Retrieved December 18, 2008. | ||

| + | * Kjeilen, Tore. [http://lexicorient.com/mauritania/ouadane.htm OUADANE: The old caravan centre] ''LookLex''. Retrieved December 18, 2008. | ||

| + | * Kjeilen, Tore. [http://lexicorient.com/mauritania/tichit.htm TICHIT: The living ghost of yesterday's glory] ''LookLex''. Retrieved December 18, 2008. | ||

* Mauny, Raymond. 1971. "The western Sudan". ''African Iron Age / Edited by P.L. Shinnie''. 66-88. {{OCLC|36788782}} | * Mauny, Raymond. 1971. "The western Sudan". ''African Iron Age / Edited by P.L. Shinnie''. 66-88. {{OCLC|36788782}} | ||

* Monteil, C. 1953. "La legende du Ouagadou et l'origine des Soninke". ''Melanges Ethnologiques''. 359-408. {{OCLC|39529024}} | * Monteil, C. 1953. "La legende du Ouagadou et l'origine des Soninke". ''Melanges Ethnologiques''. 359-408. {{OCLC|39529024}} | ||

*Ould Ebnou, Moussa. December 2000. [http://www.unesco.org/courier/2000_12/uk/doss4.htm The Treasures in Mauritania's Dunes] ''UNESCO Courier''. Retrieved December 18, 2008. | *Ould Ebnou, Moussa. December 2000. [http://www.unesco.org/courier/2000_12/uk/doss4.htm The Treasures in Mauritania's Dunes] ''UNESCO Courier''. Retrieved December 18, 2008. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*''UNESCO World Heritage Centre''. [http://whc.unesco.org/pg.cfm?cid=31&id_site=750 Ancient Ksour of Ouadane, Chinguetti, Tichitt and Oualata] Retrieved December 18, 2008. | *''UNESCO World Heritage Centre''. [http://whc.unesco.org/pg.cfm?cid=31&id_site=750 Ancient Ksour of Ouadane, Chinguetti, Tichitt and Oualata] Retrieved December 18, 2008. | ||

*Werner, Louis . November/December 2003. [http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/200306/mauritania.s.manuscripts.htm Mauritania's Manuscripts] ''Saudi Aramco World''. Retrieved December 18, 2008. | *Werner, Louis . November/December 2003. [http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/200306/mauritania.s.manuscripts.htm Mauritania's Manuscripts] ''Saudi Aramco World''. Retrieved December 18, 2008. | ||

Revision as of 00:55, 19 December 2008

| Ancient Ksour of Ouadane, Chinguetti, Tichitt and Oualata* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv, v |

| Reference | 750 |

| Region** | Arab States |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1996 (20th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

The Sahara desert is vast expanse dotted with a few oases. Though modern methods of travel are by jeep or truck, it was the camel caravans and the trade they carried from one end of the Sahara to the other end that gave rise to the four towns, known as Ksours, within Mauritania.

The winds from the deserts of Sahara and Sahel blow from the north and south respectively, into the Adrar mountain range. Amongst the sand dunes created by these winds are found the four Ksours. These are Ouadane and Chinguetti in the north, and Tichitt and Oualata in the southeast. But the height of their trade was in a bygone era. Thus the prosperity of these ancient Ksours is no more, and they are left struggling to exist amidst the encroaching desert.

Today, along with the cities of Ouadane, Tichitt and Oualata, Chinguetti has been designated as a World heritage site. The Friday Mosque of Chinguetti, is widely considered by Mauritanians to be the national symbol of the country. Mauritania's recently discovered offshore oilfield was named Chinguetti in its honor.

Ksour

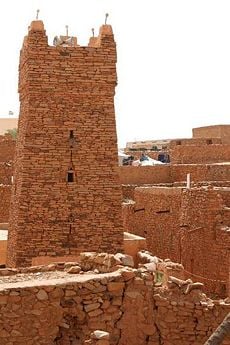

The ancient ksour are medieval towns characteristic of the Saharan ksar settlements and are well integrated into their natural environments. Ksour is the plural form of ksar.

The Arabic word, more correctly transliterated as qsar, is a term describing a village consisting of generally attached houses, often having collective granaries and other structures such as mosques, baths, ovens, and shops widespread among the oasis populations of the Northern Africa Maghreb region.

Ksour were often contained entirely within a single, continuous wall. The building material of the entire structure was normally adobe, or a combination of cut stone and adobe. These highly distinctive, fortified desert villages were the foundation from which cities evolved to become brilliant centers of Islamic culture and thought.

The word Ksar is often contained within place names across Northern Africa in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Mauritania, and is particularly prevalent on the Saharan side of the various ranges of the Atlas Mountains and the valley of the Draa River.

Ancient Ksour of Ouadane, Chinguetti, Tichitt and Oualata

The four towns of Ouadane, Chinguetti, Tichitt and Oualata are the only Mauritanian villages to have been inhabited since the Middle Ages. They were originally built along caravan routes in the eleventh century C.E. across the Sahara. The villages were important trade centers and offered a place where traders could stop for religious practice and instruction.

Along these caravan stops sprang up the necessary structures which were centered around the mosque. Homes for teachers and students were built, warehouses for traders, and inns for travelers.

These four towns display the coexistence of three types of urban fabric:[1]

- The ancient homogeneous form characterized by dense occupation, with the medina layout conforming to the topography. There are narrow alleyways but no open public spaces.

- The intermediate form reflects the ancient form except that the house plots are larger.

- The later form which is characterized by large enclosures, with one or two roomed houses.

The ancient town plan began from a central mosque, with the town radiating out from that center. Houses and courtyards increased in size the farther they were from the center. The mosques in these towns were very simple, built completely of local material, and lacked ornamentation. Each consisted of a single room or prayer hall with a vaulted ceiling. The Madrasah, or school, was a simple building within the courtyard.

The houses were simple, as they were used by nomadic people, and visited only several times per year. They were often used as storehouses. The rooms seemed to not have a fixed function, but varied upon the time of year or situation as needed.

Enclosed by walls, each town had a main entrance for caravans. Cemeteries were generally nearby, outside the walls.

Chinguetti

The ksar of Chinguetti lies on the Adrar Plateau east of the town of Atar.

Founded in the 13th century, as the center of several trans-Saharan trade routes, this tiny city continues to attract a handful of visitors who admire its spare architecture, exotic scenery and ancient libraries. The city is seriously threatened by the encroaching desert; high sand dunes mark the western boundary and several houses have been abandoned to the encroaching sand.

The indigenous Saharan architecture of older sectors of the city features reddish dry stone and mud-brick houses, with flat roofs timbered from palms. Many of the older houses feature hand-hewn doors cut from massive ancient acacia trees that have long disappeared from the surroundings. Many homes include courtyards or patios that crowd along narrow streets leading to the central mosque.

Notable buildings in the town include The Friday Mosque of Chinguetti, an ancient structure of dry stone featuring a square minaret capped with five ostrich egg finials; the former French Foreign Legion fortress; and a tall watertower. The old quarter of the Chinguetti is home to five important manuscript libraries of scientific and Qur'anic texts, with many dating from the later Middle Ages.

In recent years, the Mauritanian government, the U.S. Peace Corps, and various organizations have attempted to position the city as a center for adventurous tourists, allowing visitors to "ski" down its sand dunes, visit its libraries and appreciate the stark beauty of the Sahara.

History

The Chinguetti region has been occupied for thousands of years and once was a broad savanna. Cave paintings in the nearby Amoghar Pass feature pictures of giraffes, cows and people in a green landscape quite different from the sand dunes of the desert landscape found in the region today.

The city was originally founded in 777, and by the 11th century had become a trading center for a confederation of Berber tribes known as the Sanhadja Confederation. Soon after settling Chinguetti, the Sanhadja first interacted with and eventually melded with the Almoravids, the founders of the Moorish Empire which stretched from present-day Senegal to Spain. The city's stark unadorned architecture reflects the strict religious beliefs of the Almoravids, who spread the Malikite rite of Sunni Islam throughout the Western Maghreb.

After two centuries of decline, the city was effectively re-founded in the 13th century as a fortified cross-Saharan caravan trading center connecting the Mediterranean with Sub-Saharan Africa. Although the walls of the original fortification disappeared centuries ago, many of the buildings in the old section of the city still date from this period.

Religious importance

For centuries the city was a principal gathering place for pilgrims of the Maghreb to gather on the way to Mecca. It became known as a holy city in its own right, especially for pilgrims unable to make the long journey to the Arabian Peninsula. It also became a center of Islamic religious and scientific scholarship in West Africa. In addition to religious training, the schools of Chinguetti taught students rhetoric, law, astronomy, mathematics, and medicine. For many centuries all of Mauritania was popularly known in the Arab world as "Bilad Shinqit, “the land of Chinguetti.” Chinguetti is locally said to be the seventh most holy city of Islam. There is no recognition of this claim outside of West Africa, but whatever its ranking, the city remains one of the world's most important historical sites both in terms of the history of Islam and the history of West Africa.

Although largely abandoned to the desert, the city features a series of medieval manuscript libraries without peer in West Africa, and the area around the Rue des Savants was once famous as a gathering place for scholars to debate the finer points of Islamic law. Today its deserted streets continue to reflect the urban and religious architecture of the Moorish empire as it existed in the Middle Ages.

Chinguetti Mosque

The Great Friday Mosque of Chinguetti is an ancient center of worship created by the founders of the city of Chinguetti sometime in the thirteenth or fourteenth century. The minaret of this ancient structure is purportedly the second oldest in continuous use anywhere in the Muslim world.

Architecturally, the structure features a prayer room with four aisles as well as a double-niched symbolic door, or mihrab, pointing towards Mecca, and an open courtyard. Among its most distinctive characteristics are its spare, unmortared, split stone masonry, its square minaret tower, and its conscious lack of adornment, keeping with the strict Malikite beliefs of the city's founders. The mosque and its minaret is popularly considered the national emblem of the Islamic Republic of Mauritania.

In the 1970s the mosque was restored through a UNESCO effort, but it, along with the city itself, continues to be threatened by intense desertification.

Ouadane

Ouadane (Arabic: وادان) is located in northwestern Mauritania, lying on the Adrar Plateau, 120 kilometers (75 mi) northeast of Chinguetti. It was founded in 1147 by the Berber tribe Idalwa el Hadji and soon became an important caravan and trading center.

The village is set on a hillside, blending into the landscape. It is surrounded by an oasis, palmyrah palm trees, and sand dunes. Once an important center of camel caravans, when salt, dates and gold were the main merchandise, Ouadane has some of the most impressive ruins of Mauritania.

A Portuguese trading post was established in 1487, but the town declined from the sixteenth century. The old town, though in ruins, is still substantially intact, its main attraction being the ancient mosque.

Situated above the old village is an "upper town," a small modern settlement outside the old town's gate, inhabited by the Berber Idawalhajj tribe.

Oualata

A major trade route connected Ouadane with Oualata (Arabic: ولاته) (sometimes "Walata"), a ksar in the southeast part of the country. Oualata is believed to have been first settled by an agro-pastoral people akin to the Mandé Soninke who lived along the rocky promontories of the Tichitt-Oualata and Tagant cliffs of Mauritania. There, they built what are among the oldest stone settlements on the African continent.

The modern city was founded in the eleventh century, when it was part of the Ghana Empire. It was destroyed in 1076 but re-founded in 1224, and again became a major trading post for trans-Saharan trade and an important center of Islamic scholarship.

Oualata was a prosperous settlement, especially between the 14th and 18th centuries, such that it appeared on European maps. Trade was not its sole source of wealth; it had become a renowned intellectual center that attracted foreign students.

A century ago, this oasis was farmland that produced enough food to feed a population of several thousand inhabitants. Today, the few wind-battered palm trees are dying, half-buried in sand.[2]

Today, Oualata is home to a prized manuscript museum. Its buildings are trimmed with white drawings against a reddish-brown undercoat, making the city known for its highly decorative vernacular architecture. The designs on Oualata’s walls are the same as those still drawn on the hands and feet of Mauritanian women.

Tichit

Tichit (Arabic: تيشيت) is a partly abandoned small town at the foot of the Tagant plateau in south-central Mauritania. It was founded circa 1150 and is known for its vernacular architecture. The main industry in Tichit is date farming, and the town is also home to a small museum.

In Tichitt, fragile multi-storied houses in somber colours are all that remain of typical Mauritanian architecture in a once prosperous city.

Benefiting from its location on the route between Oualata and Ouadane, Tichitt grew into a magnificent city. The town’s multi-storied houses–with blind walls on the ground floor, a door for only opening to the outside and façades built of coloured stones–are fragile remnants of typical Mauritanian architecture. The buildings’ subdued polychrome stands in sharp contrast to the exuberant façades in Oualata, where the doors, porches, vents and windows are trimmed with white drawings against a reddish-brown undercoat. By contrast, Tichitt, located in a basin at the foot of the Adrar, is much less protected from the sand. Legend has it that seven towns have been superimposed on this site, and the one that has come down to us today is irretrievably sinking beneath the dunes. Only the upper stories of a few houses are visible–the rest has been swallowed by the sand. As recently as a century ago, this oasis was farmland that produced enough food to feed a population of several thousand inhabitants. Today, the few wind-battered palm trees are dying, half-buried in sand. The final blow came last year, when torrential rains destroyed 80 percent of the town. Luckily, the splendid mosque and its square minaret, the most beautiful building of all, survived.[3]

Only a handful of families remain. Once this was a glorious city, rich and thriving. And giving birth to a culture of great imagination, of which there still are quite evident traces. The architecture, distinct for the Tagant region, and better represented than in Tidjikja, is the main attraction of Tichit. 20-30 houses are still standing in good conditions, and are highly ornamented. The houses has the ornamented and intricate niches, that are typical for the Tagant region. The doors of some of the houses are another great attraction, made out of heavy and solid imported wood and with heavy bolts and latches. Tichit was founded in the 12th century, and was for long an important trading centre for salt.

The organisation of Tichit tells a lot of the history of the village. To the north, is the Shurfa quarter, where greenish stone is used, probably as an expression of the tribe of the Shurfa's claim of decendancy to the Prophet. Red stone is used in the southern quarter, where the Masana tribe lived. This was the blacks of the region. White stone was used for larger buildings. The Masana tribe was the largest, and they were considered good merchants, and they kept, and still keep, slaves. It must be underlined that the conditions for the slaves in most cases resembles more the ones of a contract worker (on lifetime), than the American slaves. In ancient times (we're counting 3,000 years and more now), Tachit was near the lake of Aoukar, a lake of 50,000 km². All that now is left is the salty surface, which is slowly eroded, and which is a continous theat to Tichit. The date harvest of Tichit is in the hottest summer, in July, when the fairly extensive palmeraie south of the village is the centre of all activity. Of more attractions, there are nearby rock paintings, as well as more ruins. Of these, Akreijt, to the east of Tichit is the most interesting. [4]

Notes

- ↑ UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Advisory Body Evaluation Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- ↑ Rohan Canagasabey. March 22, 2006. Ksours — Mauritania’s ancient towns of Sahara Leader Publications. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- ↑ Ould Ebnou, Moussa. December 2000. The Treasures in Mauritania's Dunes UNESCO Courier. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- ↑ Tore Kjeilen. TICHIT: The living ghost of yesterday's glory LookLex. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Archnet. Great Mosque of Chinguetti Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- Canagasabey, Rohan. March 22, 2006. Ksours — Mauritania’s ancient towns of Sahara Leader Publications. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- Kjeilen, Tore. OUADANE: The old caravan centre LookLex. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- Kjeilen, Tore. TICHIT: The living ghost of yesterday's glory LookLex. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- Mauny, Raymond. 1971. "The western Sudan". African Iron Age / Edited by P.L. Shinnie. 66-88. OCLC 36788782

- Monteil, C. 1953. "La legende du Ouagadou et l'origine des Soninke". Melanges Ethnologiques. 359-408. OCLC 39529024

- Ould Ebnou, Moussa. December 2000. The Treasures in Mauritania's Dunes UNESCO Courier. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Ancient Ksour of Ouadane, Chinguetti, Tichitt and Oualata Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- Werner, Louis . November/December 2003. Mauritania's Manuscripts Saudi Aramco World. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- World Monuments Fund. Chinguetti Mosque, Mauritania Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- Wuld Ibnū, Mūsá. 2000. "The treasures in Mauritania's dunes". Unesco Courier. 26-28. OCLC 47900029

External links

All Links Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- Atomique.net. kSar project homepage

- Mauritania Today. Chinguetti

- Prominent Palin Productions. Palin's Travels - Chinguetti

- Remi Benali. Desert Libraries

- U.S. Department of State. Mauritania

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Ksar history

- Chinguetti history

- Ouadane history

- Oualata history

- Tichit history

- Chinguetti_Mosque history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.