Manuscript

A manuscript is any document that is written by hand, as opposed to being printed or reproduced in some other way. The term may also be used for information that is hand-recorded in other ways than writing, for example inscriptions that are chiseled upon a hard material or scratched (the original meaning of graffiti) as with a knife point in plaster or with a stylus on a waxed tablet, (the way Romans made notes) or as in cuneiform writing, impressed with a pointed stylus in a flat tablet of unbaked clay. The word manuscript is derived from the Latin manu scriptus, literally "written by hand."

In publishing and academic contexts, a "manuscript" is the text submitted to the publisher or printer in preparation for publication, usually as a typescript prepared on a typewriter, or today, a printout from a PC, prepared in manuscript format.

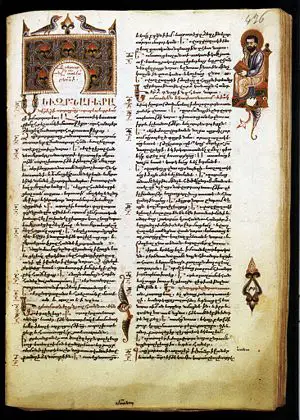

Manuscripts are not defined by their contents, which may combine writing with mathematical calculations, maps, explanatory figures or illustrations. Manuscripts may be in the form of a scroll, book, or codex. Illuminated manuscripts are enriched with pictures, border decorations, elaborately engrossed initial letters or full-page illustrations.

Manuscripts in history

The traditional abbreviations are MS for manuscript and MSS for manuscripts. (The second s is not simply the plural; by an old convention, it doubles the last letter of the abbreviation to express the plural, just as pp. means "pages".)

Before the invention of woodblock printing (in China) or by moveable type in a printing press (in Europe), all written documents had to be both produced and reproduced by hand. Historically, manuscripts were produced in form of scrolls (volumen in Latin) or books (codex, plural codices). Manuscripts were produced on vellum and other parchments, on papyrus, and on paper. In Russia birch bark documents as old as from the eleventh century have survived. In India the Palm leaf manuscript, with a distinctive long rectangular shape, was used from ancient times until the nineteenth century. Paper spread from China via the Islamic world to Europe by the fourteenth century, and by the late fifteenth century had largely replaced parchment for many purposes.

When Greek or Latin works were published, numerous professional copies were made simultaneously by scribes in a scriptorium, each making a single copy from an original that was declaimed aloud.

The oldest written manuscripts have been preserved by the perfect dryness of their Middle Eastern resting places, whether placed within sarcophagi in Egyptian tombs, or reused as mummy-wrappings, discarded in the middens of Oxyrhynchus or secreted for safe-keeping in jars and buried (Nag Hammadi library) or stored in dry caves (Dead Sea scrolls). Manuscripts in Tocharian languages, written on palm leaves, survived in desert burials in the Tarim Basin of Central Asia. Volcanic ash preserved some of the Greek library of the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum.

Ironically, the manuscripts that were being most carefully preserved in the libraries of Antiquity are virtually all lost. Papyrus has a life of at most a century or two in relatively moist Italian or Greek conditions; only those works copied onto parchment, usually after the general conversion to Christianity, have survived, and by no means all of those have.

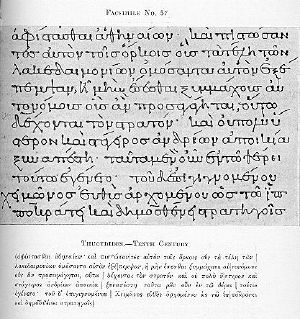

The study of the writing, or "hand" in surviving manuscripts is termed palaeography. In the Western world, from the classical period through the early centuries of the Christian era, manuscripts were written without spaces between the words (scriptio continua), which makes them especially hard for the untrained to read. Extant copies of these early manuscripts written in Greek or Latin and usually dating from the fourth century to the eighth century, are classified according to their use of either all upper case or all lower case letters. Hebrew manuscripts, such as the Dead Sea scrolls make no such differentiation. Manuscripts using all upper case letters are called majuscule, those using all lower case are called minuscule. Usually, the majuscule scripts such as uncial are written with much more care. The scribe lifted his pen between each stroke, producing an unmistakable effect of regularity and formality. On the other hand, while minuscule scripts can be written with pen-lift, they may also be cursive, that is, use little pen-lift.

Asia

In China, and later other parts of East Asia, Woodblock printing was used for books from about the seventh century. The earliest dated example is the Diamond Sutra of 868. In the Islamic world and the West, all books were in manuscript until the introduction of movable type printing in about 1450. Manuscript copying of books continued for a least a century, as printing remained expensive. Private or government documents remained hand-written until the invention of the typewriter in the late nineteenth century. Because of the likelihood of errors being introduced each time a manuscript was copied, the filiation of different version of the same text is a fundamental part of the study and criticism of all texts that have been transmitted in manuscript.

In Southeast Asia, in the first millennium, documents of sufficiently great importance were inscribed on soft metallic sheets such as copperplate, softened by refiner's fire and inscribed with a metal stylus. In the Philippines, for example, as early as 900 C.E., specimen documents were not inscribed by stylus, but were punched much like the style of dot-matrix printers in the twentieth century. This type of document was rare compared to the usual leaves and bamboo staves that were inscribed. However, neither the leaves nor paper were as durable as the metal document in the hot, humid climate. In Myanmar, the kammavaca, buddhist manuscripts, were inscribed on brass, copper or ivory sheets, and even on discarded monk robes folded and lacquered. In Italy some important Etruscan texts were similarly inscribed on thin gold plates: similar sheets have been discovered in Bulgaria. Technically, these are all inscriptions rather than manuscripts.

Manuscripts today

In the context of library science, a manuscript is defined as any hand-written item in the collections of a library or an archive; for example, a library's collection of the letters or a diary that some historical personage wrote.

In other contexts, however, the use of the term "manuscript" no longer necessarily means something that is hand-written. By analogy a "typescript" has been produced on a typewriter.

In book, magazine, and music publishing, a manuscript is an original copy of a work written by an author or composer, which generally follows standardized typographic and formatting rules. (The staff paper commonly used for handwritten music is, for this reason, often called "manuscript paper.") In film and theatre, a manuscript, or script for short, is an author's or dramatist's text, used by a theater company or film crew during the production of the work's performance or filming. More specifically, a motion picture manuscript is called a screenplay; a television manuscript, a teleplay; a manuscript for the theater, a stage play; and a manuscript for audio-only performance is often called a radio play, even when the recorded performance is disseminated via non-radio means.

In insurance, a manuscript policy is one that is negotiated between the insurer and the policyholder, as opposed to an off-the-shelf form supplied by the insurer.

Manuscripts by authors

An average manuscript page in 12 point Times Roman will contain about 23 lines of type per page and about 13 words per line, or 300 words per manuscript page. Thus if a contract between an author and publisher specifies the manuscript to be of 500 pages, it generally means 150,000 words.

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bland, David. A History of Book Illustration; The Illuminated Manuscript and the Printed Book. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969.

- Brenni, Vito Joseph. The Art and History of Book Printing: A Topical Bibliography. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1984. ISBN 0313243069 ISBN 9780313243066

- Feather, John. A Dictionary of Book History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986. ISBN 0195205200 ISBN 9780195205206

- Levarie, Norma. The Art & History of Books. New York: J.H. Heineman, 1968.

- Newton, Pat. History of Books and Printing. Hamilton, Ohio: Fort Hamilton Press, 1976.

- Tanselle, G. Thomas. The History of Books As a Field of Study: A Paper. Chapel Hill: Hanes Foundation, Rare Book Collection/Academic Affairs Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1981.

- Winckler, Paul A. History of Books and Printing: A Guide to Information Sources. Books, publishing, and libraries information guide series, v. 2. Detroit, Mich: Gale Research Co, 1979. ISBN 0810314088 ISBN 9780810314085

- ———. Reader in the History of Books and Printing. Readers in librarianship and information science, 26. Englewood, Colo: Information Handling Services, 1978. ISBN 0910972788 ISBN 9780910972789

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.