Ehrenburg, Ilya

| (36 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}} | |

| + | {{epname|Ehrenburg, Ilya}} | ||

| + | {{Infobox writer <!-- for more information see [[:Template:Infobox writer/doc]] --> | ||

| + | | name = Ilya Ehrenburg | ||

| + | | image = Ilya Ehrenburg 1960s.jpg | ||

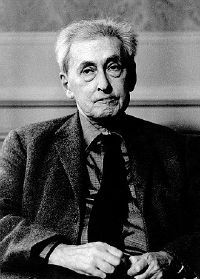

| + | | caption = Ilya Ehrenburg in the 1960s | ||

| + | | birth_date = {{OldStyleDate|January 26|1891|January 14}} | ||

| + | | birth_place = [[Kyiv|Kiev]], [[Kiev Governorate]], [[Russian Empire]]<br />(now [[Kyiv]], [[Ukraine]]) | ||

| + | | death_date = {{death date and age|mf=yes|1967|8|31|1891|1|26}} | ||

| + | | death_place = [[Moscow]], [[Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic|Russian SFSR]], [[Soviet Union]]<br />(now [[Moscow]], [[Russia]]) | ||

| + | | magnum_opus = ''Julio Jurenito'', '' [[The Thaw (novel)|The Thaw]]'' | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | '''Ilya Grigoryevich Ehrenburg''' ({{lang-ru|Илья́ Григо́рьевич Эренбу́рг}}, {{IPA-ru|ɪˈlʲja grʲɪˈgorʲɪvɪtɕ ɪrʲɪnˈburk}}) (January 27, 1891 – August 31, 1967) was a Soviet [[writer]], [[Journalism|journalist]], and [[Propaganda|propagandist]], whose 1954 novel, ''The Thaw,'' lent its name to the [[Khrushchev Thaw]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ehrenburg was a controversial figure in Soviet literature. He began his career as a journalist writing anti-German [[propaganda]] during [[World War II]]. After experiencing the excesses of [[Stalinism]], he became a critic of the Soviet system, but, nonetheless remained a part of it. For this reason he was not well received in the [[dissident]] community, many of whom suffered great consequences for their protest. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | His novel, ''The Thaw,'' gave expression to many of the problems of Soviet society and of the literary policy of [[Socialist realism]]. From within the socialist realist tradition, he tacitly embedded its utopian pretensions, demonstrating how Stalinism had nullified its [[utopia|utopian hopes]]. | ||

==Life and work== | ==Life and work== | ||

| − | Ehrenburg was a [[anti-establishment|revolutionary]] as a teenager, a disenchanted [[poet]] in his youth, writing [[Roman Catholicism|Catholic]] poems despite his [[Jewish]] background, a follower of [[Vladimir Lenin|Lenin]] | + | Ehrenburg was a [[anti-establishment|revolutionary]] as a teenager, a disenchanted [[poet]] in his youth, writing [[Roman Catholicism|Catholic]] poems despite his [[Jewish]] background, a follower of [[Vladimir Lenin|Lenin]] who then became an anti-[[Bolshevik]] and sensitive journalist. He lived in [[Paris]] for many years before and after the [[October Revolution]], serving as a foreign editor of Soviet newspapers, returning at intervals to the USSR. |

| − | ===Wartime | + | ===Wartime propaganda=== |

| + | Later, he returned to the USSR where he was hired to write Soviet [[propaganda]], while occasionally defending his views with boldness against [[Stalin]] or government mouthpieces. Ehrenburg was one of many Soviet writers, along with [[Konstantin Simonov]] and [[Aleksey Surkov]], who "lent their literary talents to the [[Anti-German sentiment|hate campaign" against Germans]] during [[World War II]].<ref name="Figes">Orlando Figes, ''The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia'' (Metropolitan Books, 2007, ISBN 978-0805074611). </ref> His article, "Kill the German" published in 1942—when German troops were deeply within Soviet territory—became a widely publicized example of this campaign, along with poem "Kill him!" by Simonov. The article declared that Germans "are not humans."<ref>[http://www.sovlit.net/bios/ehrenburg.html Ilya Ehrenburg] ''Encyclopedia of Soviet Writers''. Retrieved January 22, 2023.</ref> Soviet Officers like [[Lev Kopelev]], who opposed such rhetoric, were accused of opposing Ehrenburg and "compassion towards the enemy."<ref>Lev Kopelev, ''To Be Preserved Forever ("Хранить вечно")'' (Lippincott, 1977, ISBN 978-0397011407).</ref> Ehrenburg himself was criticized by [[Georgy Aleksandrov]] in a [[Pravda]] article in April 1945, who called his views towards the Germans over-simplifying and an "exaggeration" as it has never been the purpose of Soviet policy to wipe out the German people. When Ehrenburg received letters from frontline soldiers accusing him of having changed his position and of standing for softness towards Germans, he replied he had not changed his position, as he had always stood for "justice, not revenge."<ref>Carola Tischler, "Die Vereinfachungen des Genossen Erenburg. Eine Endkriegs- und eine Nachkriegskontroverse," in Elke Scherstjanoi (ed.), ''Rotarmisten schreiben aus Deutschland'' (Briefe von der Front, 2011, ISBN 359811656X), 336.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Ehrenburg a was prominent member of the [[Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee]]. Ehrenburg fell in disgrace at that time and it is estimated, that Aleksandrov's article was a signal of change in Stalin's policy towards Germany.<ref>Joshua Rubenstein, ''Tangled Loyalties: The Life and Times of Ilya Ehrenburg'' (Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 1999, ISBN 0817309632).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Ehrenburg a was prominent member of the [[Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee]]. Ehrenburg fell in disgrace at that time and it is estimated, that Aleksandrov's article was a signal of change in Stalin's policy towards Germany.<ref>Joshua Rubenstein | ||

===Postwar writings=== | ===Postwar writings=== | ||

| − | Ehrenburg is well known for his writing, especially his memoirs, which contain many portraits of interest to literary historians and biographers. Together with fellow journalist and writer, [[Vasily Grossman]], Ehrenburg edited The ''[[Black Book (World War II)|Black Book]]'' | + | Ehrenburg is well known for his writing, especially his memoirs, which contain many portraits of interest to literary historians and biographers. Together with fellow journalist and writer, [[Vasily Grossman]], Ehrenburg edited The ''[[Black Book (World War II)|Black Book]],'' a collaborative effort by the [[Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee]] (JAC) and members of the American Jewish community to document the anti-Jewish crimes of [[the Holocaust]] and the participation of Jews in the fighting and the [[resistance movement]] against the [[Nazism|Nazis]] during [[World War II]]. |

| − | Ehrenburg and Grossman served as war reporters for the [[Red Army]]. Grossman's documentary reports of the opening of the [[Treblinka extermination camp|Treblinka]] and [[Majdanek]] [[extermination camp]]s were some of the first eyewitness | + | Ehrenburg and Grossman served as war reporters for the [[Red Army]]. Grossman's documentary reports of the opening of the [[Treblinka extermination camp|Treblinka]] and [[Majdanek]] [[extermination camp]]s were some of the first eyewitness accounts—as early as 1943—of what later became known as the [[Shoah]]. His article, ''The Treblinka Hell,'' was disseminated at the [[Nuremberg Trials]] as a document for the prosecution. |

| − | In | + | In 1944–1945, based on their own experiences and on other documents they collected, Ehrenburg and Grossman produced two volumes under the title ''Murder of the People'' in [[Yiddish]] and handed the manuscript to the JAC. Copies were sent to the [[United States]], [[Israel]] (then the [[British mandate of Palestine]]) and [[Romania]] in 1946, and excerpts were published in the United States in English under the title ''Black Book'' that same year. A handwritten manuscript of the Book is held at [[Yad Vashem]]. |

| − | The Book was partially printed in the Soviet Union by the Yiddish publisher ''Der Emes'' | + | The Book was partially printed in the Soviet Union by the Yiddish publisher ''Der Emes,'' however the entire edition, the typefaces, as well as the manuscript, were destroyed. First the censors ordered changes in the text to conceal the specifically anti-Jewish character of the atrocities and to downplay the role of [[Ukrainians]] who worked as Nazi police officers. Then, in 1948, the Soviet edition of the book was scrapped completely. The collection of original documents that Ehrenburg handed down to the [[Vilnius]] Jewish Museum after the war was secretly returned to him upon the Museum's termination in 1948. The JAC was also disbanded, its members [[Great Purge|purged]] at the outset of the state campaign against the "[[rootless cosmopolitan]]s," a Soviet euphemism for Jews. |

A Russian-language edition of the Black Book was published in [[Jerusalem]] in 1980, and finally in [[Kiev]], Ukraine in 1991. | A Russian-language edition of the Black Book was published in [[Jerusalem]] in 1980, and finally in [[Kiev]], Ukraine in 1991. | ||

| − | ===The Thaw=== | + | ===''The Thaw''=== |

| − | In 1954, Ehrenburg published a novel titled ''The Thaw'' that tested limits of censorship in the post-Stalin [[Soviet Union]]. Published in the literary journal Новый Мир (''Novyi Mir'' | + | In 1954, Ehrenburg published a novel titled ''The Thaw'' that tested limits of censorship in the post-Stalin [[Soviet Union]]. Published in the literary journal Новый Мир (''Novyi Mir,'' or New World), it revolved around three characters. One was factory boss, Ivan Zhuravlev. In a typical novel of [[Socialist Realism]], this character would be the hero, but in Ehrenburg's novel he is corrupt and despotic—"a little Stalin." The boss's wife could not bear to stay with him and left the despot during the spring ''thaw'' that gave her the courage. The second, Vladimir Pukhov, is a government artist. He is contrasted with the third character, Saburov, who served not the government but the dictates of his conscience. While Pukhov enjoys some success, he compares himself to Saburov, who is true to the dictates of art. The novel does not follow the prescribed model of Socialist realism. The purported hero is a dishonorable character, and a poor reflection on the virtues of [[communism]]. The most sympathetic characters are not the ones who represent the virtues of Soviet society. |

| − | In August 1954, [[Konstantin Simonov]] attacked ''The Thaw'' in articles published in [[Literaturnaya gazeta]], arguing that such writings are too dark and do not serve the Soviet state <ref name="Figes" | + | In August 1954, [[Konstantin Simonov]] attacked ''The Thaw'' in articles published in [[Literaturnaya gazeta]], arguing that such writings are too dark and do not serve the Soviet state.<ref name="Figes"/> The novel gave its name to [[Khrushchev Thaw]]. |

===Death=== | ===Death=== | ||

| − | Ehrenburg died in 1967 of prostate and bladder cancer, and was interred in [[Novodevichy Cemetery]] in [[Moscow]], where his gravestone is adorned with a reproduction of his portrait drawn by his friend, famous founder of the [[Cubism|Cubist]] [[art]] movement, [[Pablo Picasso]]. | + | Ehrenburg died in 1967, of prostate and bladder cancer, and was interred in [[Novodevichy Cemetery]] in [[Moscow]], where his gravestone is adorned with a reproduction of his portrait drawn by his friend, famous founder of the [[Cubism|Cubist]] [[art]] movement, [[Pablo Picasso]]. |

==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

| − | + | "Ehrenburg had a tangled record as a reformer and Soviet loyalist…. Although many of his friends disappeared in the purges, he managed to survive, returning to Moscow in 1941 and working as a war correspondent…. In retrospect, [The] THAW tends to honor the tenets of Stalinist culture more than it defies them."<ref> James von Geldern, [https://soviethistory.msu.edu/1954-2/the-thaw/ The Thaw] ''Seventeen Moments in Soviet History''. Retrieved January 22, 2023.</ref> In fact, Ehrenburg's suggestion that a thaw had occurred in Soviet society after the death of Stalin seems more like prophecy than description. It was still too early in 1954 for a substantial shift in cultural policy, which would take place in fits and starts over the next decade until it would ultimately become attached to cultural policies of [[Nikita Khrushchev]]. | |

| − | + | Ehrenburg received the Stalin Prize in 1942 and 1948, and the Lenin Peace Prize in 1952. He would also serve as a Deputy to the Supreme Soviet beginning in 1950. | |

| − | + | ===Influence=== | |

| + | [[Alan Furst]]—considered by to be many America's premier writer of espionage fiction—found much of Ehrenburg's life and work so riveting that he modeled the central character in his 1991 novel, ''Dark Star,'' on the Russian writer. Addressing the degree to which fact and fiction sometimes overlap, Furst said, "(a particular character) was modeled on a number of people, although I've written about many people who did exist. Andre Szara in ''Dark Star,'' for example, is based on the Russian writer Ilya Ehrenburg" (''Boston Globe'' interview, June 4, 2006). Six weeks later, in another interview, his comments were rather more qualified: "None of my characters are meant to be representations of real people. But in fact, in ''Dark Star'' the lead character is a Russified Polish Jew, a foreign correspondent for ''[[Pravda]]''. So are we talking about Ilya Ehrenburg? Not really. But he's like that." | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Vladimir Nabokov]] wrote of him: "As a writer he doesn't exist, Ehrenburg. He is a journalist. He was always corrupt".<ref>Andrew Field, ''The Life and Art of Vladimir Nabokov'' (New York: Crown Publishers, Inc, 1977, ISBN 0517561131).</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | <references/> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | *Field, Andrew. ''The Life and Art of Vladimir Nabokov''. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc, 1977. ISBN 0517561131 | |

| + | *Figes, Orlando. ''The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia''. Metropolitan Books, 2007. ISBN 978-0805074611 | ||

| + | *Kopelev, Lev. ''To Be Preserved Forever''. Lippincott, 1977. ISBN 978-0397011407 | ||

| + | *Rubenstein, Joshua. ''Tangled Loyalties. The Life and Times of Ilya Ehrenburg''. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1999. ISBN 0817309632 | ||

| + | *Scherstjanoi, Elke (ed.). ''Rotarmisten schreiben aus Deutschland. Briefe von der Front (1945) und historische Analysen. Texte und Materialien zur Zeitgeschichte.'' Bd. 14. K.G. Saur, München 2011. ISBN 359811656X | ||

| + | |||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | *[ | + | All links retrieved January 22, 2023. |

| − | + | *[https://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/black_book/Black_Book.html The Black Book] Translation of ''Chornaya Kniga'' | |

| − | *[ | + | *[https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/4636/the-art-of-fiction-no-26-ilya-ehrenburg Ilya Ehrenburg, The Art of Fiction No. 26] Interviewed by Olga Carlisle, ''The Paris Review'', 1961. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | [[category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | ||

Latest revision as of 23:54, 22 January 2023

Ilya Ehrenburg in the 1960s | |

| Born: | January 26 [O.S. January 14] 1891 Kiev, Kiev Governorate, Russian Empire (now Kyiv, Ukraine) |

|---|---|

| Died: | August 31 1967 (aged 76) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union (now Moscow, Russia) |

| Magnum opus: | Julio Jurenito, The Thaw |

Ilya Grigoryevich Ehrenburg (Russian: Илья́ Григо́рьевич Эренбу́рг, Russian pronunciation: [ɪˈlʲja grʲɪˈgorʲɪvɪtɕ ɪrʲɪnˈburk]) (January 27, 1891 – August 31, 1967) was a Soviet writer, journalist, and propagandist, whose 1954 novel, The Thaw, lent its name to the Khrushchev Thaw.

Ehrenburg was a controversial figure in Soviet literature. He began his career as a journalist writing anti-German propaganda during World War II. After experiencing the excesses of Stalinism, he became a critic of the Soviet system, but, nonetheless remained a part of it. For this reason he was not well received in the dissident community, many of whom suffered great consequences for their protest.

His novel, The Thaw, gave expression to many of the problems of Soviet society and of the literary policy of Socialist realism. From within the socialist realist tradition, he tacitly embedded its utopian pretensions, demonstrating how Stalinism had nullified its utopian hopes.

Life and work

Ehrenburg was a revolutionary as a teenager, a disenchanted poet in his youth, writing Catholic poems despite his Jewish background, a follower of Lenin who then became an anti-Bolshevik and sensitive journalist. He lived in Paris for many years before and after the October Revolution, serving as a foreign editor of Soviet newspapers, returning at intervals to the USSR.

Wartime propaganda

Later, he returned to the USSR where he was hired to write Soviet propaganda, while occasionally defending his views with boldness against Stalin or government mouthpieces. Ehrenburg was one of many Soviet writers, along with Konstantin Simonov and Aleksey Surkov, who "lent their literary talents to the hate campaign" against Germans during World War II.[1] His article, "Kill the German" published in 1942—when German troops were deeply within Soviet territory—became a widely publicized example of this campaign, along with poem "Kill him!" by Simonov. The article declared that Germans "are not humans."[2] Soviet Officers like Lev Kopelev, who opposed such rhetoric, were accused of opposing Ehrenburg and "compassion towards the enemy."[3] Ehrenburg himself was criticized by Georgy Aleksandrov in a Pravda article in April 1945, who called his views towards the Germans over-simplifying and an "exaggeration" as it has never been the purpose of Soviet policy to wipe out the German people. When Ehrenburg received letters from frontline soldiers accusing him of having changed his position and of standing for softness towards Germans, he replied he had not changed his position, as he had always stood for "justice, not revenge."[4]

Ehrenburg a was prominent member of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. Ehrenburg fell in disgrace at that time and it is estimated, that Aleksandrov's article was a signal of change in Stalin's policy towards Germany.[5]

Postwar writings

Ehrenburg is well known for his writing, especially his memoirs, which contain many portraits of interest to literary historians and biographers. Together with fellow journalist and writer, Vasily Grossman, Ehrenburg edited The Black Book, a collaborative effort by the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC) and members of the American Jewish community to document the anti-Jewish crimes of the Holocaust and the participation of Jews in the fighting and the resistance movement against the Nazis during World War II.

Ehrenburg and Grossman served as war reporters for the Red Army. Grossman's documentary reports of the opening of the Treblinka and Majdanek extermination camps were some of the first eyewitness accounts—as early as 1943—of what later became known as the Shoah. His article, The Treblinka Hell, was disseminated at the Nuremberg Trials as a document for the prosecution.

In 1944–1945, based on their own experiences and on other documents they collected, Ehrenburg and Grossman produced two volumes under the title Murder of the People in Yiddish and handed the manuscript to the JAC. Copies were sent to the United States, Israel (then the British mandate of Palestine) and Romania in 1946, and excerpts were published in the United States in English under the title Black Book that same year. A handwritten manuscript of the Book is held at Yad Vashem.

The Book was partially printed in the Soviet Union by the Yiddish publisher Der Emes, however the entire edition, the typefaces, as well as the manuscript, were destroyed. First the censors ordered changes in the text to conceal the specifically anti-Jewish character of the atrocities and to downplay the role of Ukrainians who worked as Nazi police officers. Then, in 1948, the Soviet edition of the book was scrapped completely. The collection of original documents that Ehrenburg handed down to the Vilnius Jewish Museum after the war was secretly returned to him upon the Museum's termination in 1948. The JAC was also disbanded, its members purged at the outset of the state campaign against the "rootless cosmopolitans," a Soviet euphemism for Jews.

A Russian-language edition of the Black Book was published in Jerusalem in 1980, and finally in Kiev, Ukraine in 1991.

The Thaw

In 1954, Ehrenburg published a novel titled The Thaw that tested limits of censorship in the post-Stalin Soviet Union. Published in the literary journal Новый Мир (Novyi Mir, or New World), it revolved around three characters. One was factory boss, Ivan Zhuravlev. In a typical novel of Socialist Realism, this character would be the hero, but in Ehrenburg's novel he is corrupt and despotic—"a little Stalin." The boss's wife could not bear to stay with him and left the despot during the spring thaw that gave her the courage. The second, Vladimir Pukhov, is a government artist. He is contrasted with the third character, Saburov, who served not the government but the dictates of his conscience. While Pukhov enjoys some success, he compares himself to Saburov, who is true to the dictates of art. The novel does not follow the prescribed model of Socialist realism. The purported hero is a dishonorable character, and a poor reflection on the virtues of communism. The most sympathetic characters are not the ones who represent the virtues of Soviet society.

In August 1954, Konstantin Simonov attacked The Thaw in articles published in Literaturnaya gazeta, arguing that such writings are too dark and do not serve the Soviet state.[1] The novel gave its name to Khrushchev Thaw.

Death

Ehrenburg died in 1967, of prostate and bladder cancer, and was interred in Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow, where his gravestone is adorned with a reproduction of his portrait drawn by his friend, famous founder of the Cubist art movement, Pablo Picasso.

Legacy

"Ehrenburg had a tangled record as a reformer and Soviet loyalist…. Although many of his friends disappeared in the purges, he managed to survive, returning to Moscow in 1941 and working as a war correspondent…. In retrospect, [The] THAW tends to honor the tenets of Stalinist culture more than it defies them."[6] In fact, Ehrenburg's suggestion that a thaw had occurred in Soviet society after the death of Stalin seems more like prophecy than description. It was still too early in 1954 for a substantial shift in cultural policy, which would take place in fits and starts over the next decade until it would ultimately become attached to cultural policies of Nikita Khrushchev.

Ehrenburg received the Stalin Prize in 1942 and 1948, and the Lenin Peace Prize in 1952. He would also serve as a Deputy to the Supreme Soviet beginning in 1950.

Influence

Alan Furst—considered by to be many America's premier writer of espionage fiction—found much of Ehrenburg's life and work so riveting that he modeled the central character in his 1991 novel, Dark Star, on the Russian writer. Addressing the degree to which fact and fiction sometimes overlap, Furst said, "(a particular character) was modeled on a number of people, although I've written about many people who did exist. Andre Szara in Dark Star, for example, is based on the Russian writer Ilya Ehrenburg" (Boston Globe interview, June 4, 2006). Six weeks later, in another interview, his comments were rather more qualified: "None of my characters are meant to be representations of real people. But in fact, in Dark Star the lead character is a Russified Polish Jew, a foreign correspondent for Pravda. So are we talking about Ilya Ehrenburg? Not really. But he's like that."

Vladimir Nabokov wrote of him: "As a writer he doesn't exist, Ehrenburg. He is a journalist. He was always corrupt".[7]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Orlando Figes, The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia (Metropolitan Books, 2007, ISBN 978-0805074611).

- ↑ Ilya Ehrenburg Encyclopedia of Soviet Writers. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ↑ Lev Kopelev, To Be Preserved Forever ("Хранить вечно") (Lippincott, 1977, ISBN 978-0397011407).

- ↑ Carola Tischler, "Die Vereinfachungen des Genossen Erenburg. Eine Endkriegs- und eine Nachkriegskontroverse," in Elke Scherstjanoi (ed.), Rotarmisten schreiben aus Deutschland (Briefe von der Front, 2011, ISBN 359811656X), 336.

- ↑ Joshua Rubenstein, Tangled Loyalties: The Life and Times of Ilya Ehrenburg (Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 1999, ISBN 0817309632).

- ↑ James von Geldern, The Thaw Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ↑ Andrew Field, The Life and Art of Vladimir Nabokov (New York: Crown Publishers, Inc, 1977, ISBN 0517561131).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Field, Andrew. The Life and Art of Vladimir Nabokov. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc, 1977. ISBN 0517561131

- Figes, Orlando. The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia. Metropolitan Books, 2007. ISBN 978-0805074611

- Kopelev, Lev. To Be Preserved Forever. Lippincott, 1977. ISBN 978-0397011407

- Rubenstein, Joshua. Tangled Loyalties. The Life and Times of Ilya Ehrenburg. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1999. ISBN 0817309632

- Scherstjanoi, Elke (ed.). Rotarmisten schreiben aus Deutschland. Briefe von der Front (1945) und historische Analysen. Texte und Materialien zur Zeitgeschichte. Bd. 14. K.G. Saur, München 2011. ISBN 359811656X

External links

All links retrieved January 22, 2023.

- The Black Book Translation of Chornaya Kniga

- Ilya Ehrenburg, The Art of Fiction No. 26 Interviewed by Olga Carlisle, The Paris Review, 1961.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.