Hecate

Hecate, Hekate (Hekátē), or Hekat was originally a goddess of the wilderness and childbirth, naturalized early in Thrace, but originating among the Carians of Anatolia,[1] and where Hekate remained a great goddess into historical times. Indeed, the earliest inscription describing the goddess has been found in late archaic Miletus, close to Caria, where Hecate is a protector of entrances.[2]

Regardless of her foreign provenance, popular cults venerating Hecate as a mother goddess gradually integrated her persona into the religious landscape of the Greeks. In the process, the character of the goddess and her cult changed considerably, as the fertility and motherhood elements of her personality lost some of their importance. Instead, she was ultimately transformed into a goddess of sorcery, who came to be known as the 'Queen of Ghosts', a transformation that was particularly pronounced in Ptolemaic Alexandria. It was in this sinister guise she was transmitted to post-Renaissance culture. Today, she is often seen as a goddess of witchcraft and Wicca.

One aspect of Hecate (specifically, her omniscient, three-faced form) is represented in the Roman Trivia.

Mythology

Hecate is a pre-Olympian chthonic goddess, not easily assimilated. The Greek sources do not offer a story of her parentage, beyond the Theogony, or of her relations in the Greek pantheon: Sometimes Hecate is a Titaness, daughter of Perses and Asteria, and a mighty helper and protector of mankind. Her continued presence was explained by asserting that, because she was the only Titan that aided Zeus in the battle of gods and Titans, she was not banished into the underworld realms after their defeat by the Olympians.

It is also told that she is the daughter of Demeter or Pheraia. Hecate, like Demeter, was a goddess of the earth and fertility.[3] Sometimes she is called a daughter of Zeus, a trait she shares, however, with Athena and even Aphrodite.

She appears in the Homeric "Hymn to Demeter" and in Hesiod's Theogony, where she is promoted strongly as a great goddess.

Hesiod records that she was the offspring of two Titans, Asteria and Persus. In Theogony he ascribed to Hecate such wide-ranging and fundamental powers, that it is hard to resist seeing such a deity as a figuration of the Great Goddess, though as a good Olympian Hesiod ascribes her powers as the "gift" of Zeus:

- Asteria of happy name, whom Perses once led to his great house to be called his dear wife. And she conceived and bare Hecate whom Zeus the son of Cronos honoured above all. He gave her splendid gifts, to have a share of the earth and the unfruitful sea. She received honour also in starry heaven, and is honoured exceedingly by the deathless gods.... The son of Cronos did her no wrong nor took anything away of all that was her portion among the former Titan gods: but she holds, as the division was at the first from the beginning, privilege both in earth, and in heaven, and in sea (Theogony 404-452).

Hesiod emphasizes that Hecate was an only child, the daughter of Asteria, a star-goddess who was the sister of Leto, the mother of Artemis and Apollo. Grandmother of the three cousins was Phoebe the ancient Titaness who personified the moon. Hecate was a reappearance of Phoebe, a moon goddess herself, who appeared in the dark of the moon.

His inclusion and praise of Hecate in Theogony is troublesome for scholars in that he seems fulsomely to praise her attributes and responsibilities in the ancient cosmos even though she is both relatively minor and foreign. It is theorized [4] that Hesiod’s original village had a substantial Hecate following and that his inclusion of her in the Theogony was his own way to boost the home-goddess for unfamiliar hearers.

There are two versions of Hecate that emerge in Greek myth. The lesser role integrates Hecate while not diminishing Artemis. In this version [4]Hecate is a mortal priestess who is commonly associated with Iphigeneia and scorns and insults Artemis, eventually leading to her suicide. Artemis then adorns the dead body with jewelry and whispers for her spirit to rise and become her Hecate, and act similar to Nemesis as an avenging spirit, but solely for injured women. Such myths where a home god sponsors or ‘creates’ a foreign god were widespread in ancient cultures as a way of integrating foreign cults. Additionally, as Hecate’s cult grew, her figure was added to the myth of the birth of Zeus [4] as one of the midwives that hid the child, while Cronus consumed the deceiving rock handed to him by Gaia.

The second version helps to explain how Hecate gains the title of the "Queen of Ghosts" and her role as a goddess of sorcery. Similar to totems of Hermes—herms— placed at borders as a ward against danger, images of Hecate, as a liminal goddess, could also serve in such a protective role. It became common to place statues of the goddess at the gates of cities, and eventually domestic doorways. Over time, the association of keeping out evil spirits led to the belief that if offended Hecate could also let in evil spirits. Thus invocations to Hecate arose as her the dogg governess of the borders between the normal world and the spirit world [4].

The transition of the figure of Hekate can be traced in fifth-century Athens. In two fragments of Aeschylus she appears as a great goddess. In Sophocles and Euripides she has become the mistress of witchcraft and keres.

Eventually, Hecate’s power resembled that of sorcery. Medea, who was a priestess of Hecate, used witchcraft in order to handle magic herbs and poisons with skill, and to be able to stay the course of rivers [citation needed], or check the paths of the stars and the moon.

<powell, 225 (23, 56), 235 (403)> Implacable Hecate has been called "tender-hearted", a euphemism perhaps to emphasize her concern with the disappearance of Persephone, when she addressed Demeter with sweet words when the goddess was distressed. She later became Persephone's minister and close companion in the Underworld.

Although she was never truly incorporated among the Olympian gods, the modern understanding of Hecate is derived from the syncretic Hellenistic culture of Alexandria. In the magical papyri of Ptolemaic Egypt, she is called the she-dog or bitch, and her presence is signified by the barking of dogs. She sustained a large following as a goddess of protection and childbirth. In late imagery she also has two ghostly dogs as servants by her side.

Relationship with Humanity

Her gifts towards mankind are all-encompassing, Hesiod tells:

- "Whom she will she greatly aids and advances: she sits by worshipful kings in judgement, and in the assembly whom her will is distinguished among the people. And when men arm themselves for the battle that destroys men, then the goddess is at hand to give victory and grant glory readily to whom she will. Good is she also when men contend at the games, for there too the goddess is with them and profits them: and he who by might and strength gets the victory wins the rich prize easily with joy, and brings glory to his parents. And she is good to stand by horsemen, whom she will: and to those whose business is in the grey discomfortable sea, and who pray to Hecate and the loud-crashing Earth-Shaker, easily the glorious goddess gives great catch, and easily she takes it away as soon as seen, if so she will. She is good in the byre with Hermes to increase the stock. The droves of kine and wide herds of goats and flocks of fleecy sheep, if she will, she increases from a few, or makes many to be less".

Goddess of the crossroads

Hecate had a special role at three-way crossroads, where the Greeks set poles with masks of each of her heads facing different directions [citation needed]

The crossroad aspect of Hecate stems from her original sphere as a goddess of the wilderness and untamed areas. This led to sacrifice in order for safe travel into these areas. This role is similar to lesser Hermes, that is, a god of liminal points or boundaries.

Hecate is the Greek version of Trivia "the three ways" in Roman mythology. Eligius in the 7th century reminded his recently converted flock in Flanders "No Christian should make or render any devotion to the gods of the trivium, where three roads meet, to the fanes or the rocks, or springs or groves or corners", acts the Druids often did. see Hectite: [1]

Goddess of sorcery

The goddess of sorcery or magic is Hecate's most common modern title. Hecate was the goddess who appeared most often in magical texts such as the Greek Magical Papyri and curse tablets, along with Hermes.

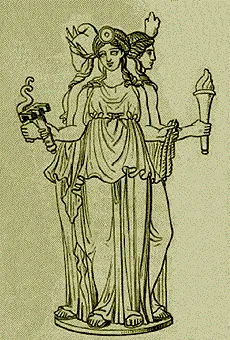

Representations

The earliest depictions of Hecate are single faced, not triplicate. Summarizing the early trends in artistic depictions of the goddess, Lewis Richard Farnell writes:

- The evidence of the monuments as to the character and significance of Hekate is almost as full as that of the literature. But it is only in the later period that they come to express her manifold and mystic nature. Before the fifth century there is little doubt that she was usually represented as of single form like any other divinity, and it was thus that the Boeotian poet ([Hesiod]) imagined her, as nothing in his verses contains any allusion to a triple formed goddess. The earliest known monument is a small terracotta found in Athens, with a dedication to Hekate (Plate XXXVIII. a), in writing of the style of the sixth century. The goddess is seated on a throne with a chaplet bound round her head; she is altogether without attributes and character, and the only value of this work, which is evidently of quite a general type and gets a special reference and name merely from the inscription, is that it proves the single shape to be her earlier from, and her recognition at Athens to be earlier than the Persian invasion.[5]

The second-century traveller Pausanias stated that Hecate was first depicted in triplicate by the sculptor Alkamenes in the Greek Classical period of the late 5th century. Some classical portrayals, depict her in this form holding a torch, a key and a serpent. Others continue to depict her in singular form. Hecate's triplicity is represented in the vast frieze of the great Pergamon Altar, which depicts the Titanomachy (the mythic battle between the Olympians and the Titans). In the Argolid, near the shrine of the Dioscuri, Pausanias also tells of a temple of Hecate opposite the sanctuary of Eilethyia: "The image is a work of Scopas. This one is of stone, while the bronze images opposite, also of Hekate, were made respectively by Polycleitus and his brother Naucydes, son of Mothon."[6]

In general, the representations of Hecate seem to follow a similar progression to the development of her cultic and mythic forms, evolving in tandem with the public conception of the goddess. Thus, as her characterization began to assume greater elements of the chthonic and the uncanny, visual representations followed suit.[7]

Cult of Hecate

Despite popular belief, Hecate was not originally a Greek goddess. The roots of Hecate seem to be in the Carians of Asia Minor.[8] She appears in Homer's "Hymn to Demeter" and in Hesiod's Theogony, where she is promoted strongly as a great goddess. The place of origin of her cult is uncertain, but it is thought[1] that she had popular cult followings in Thrace. Her most important sanctuary was Lagina, a theocratic city-state in which the goddess was served by eunuchs[1]. Lagina, where the famous temple of Hecate drew great festal assemblies every year, lay close to the originally Macedonian colony of Stratonikea, where she was the city's patroness.[9]. In Thrace she played a role similar to that of lesser-Hermes, namely a governess of liminal points and the wilderness, bearing little resemblance to the night-walking crone she became. Additionally, this led to her role of aiding women in childbirth and the raising of young men.

There was a fane sacred to Hecate as well in the precincts of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, where the eunuch priests, megabyzi, officiated [10].

The case for Hecate's origin's in Anatolia is bolstered by the fact that this is the only region where theophoric names incorporating "Hecate" are attested. See: Theodor Kraus, Hekate: Studien zu Wesen u. Bilde der Göttin in Kleinasien u. Griechenland (Heidelberg) 1960. Kraus offers the first modern comprehensive discussion of Hecate in monuments and material culture.

In this region, her cult was particularly well established at Lagina. See William Berg, who notes, "There is a temple of Hecate at Lagina in Caria where the goddess was worshipped as sōteira, mēgiste, and epiphanestatē; her exalted rank and function here are unmatched in cults of Hecate elsewhere" (128). See also Kraus 1960:12.

Hesiod's Theogony:

- "For to this day, whenever any one of men on earth offers rich sacrifices and prays for favour according to custom, he calls upon Hecate. Great honour comes full easily to him whose prayers the goddess receives favourably, and she bestows wealth upon him; for the power surely is with her".

As her cult spread into areas of Greece it presented a conflict, as Hecate’s role was already filled by other more prominent gods in the Greek pantheon, above all by Artemis, and by more archaic figures, such as Nemesis.

<curse tablets (Price 101, Mikalson 38)>

Festivals

Hecate was worshipped by both the Greeks and the Romans who had their own festivals dedicated to her. According to Ruickbie (2004:19) the Greeks observed two days sacred to Hecate, one on the 13th of August and one on the 30th of November, whilst the Romans observed the 29th of every month as her sacred day.

Still other reports place a Celtic celebration of Hecate night fifteen days after All Hallows Eve, or what is known today as Halloween. In some places this is extended to what is called Hecate week and lasts seven days.

Cross-cultural parallels

The figure of Hecate can often be associated with the figure of Isis in Egyptian myth, mainly due to her role as sorceress. In Hebrew myth she is often compared to the figure of Lilith and the Whore of Babylon in later Christian tradition. Both were symbols of liminal points, and Lilith also has a role in sorcery. Some scholars ultimately compare her to the Virgin Mary. She is also comperable to Hel of Nordic myth in her underworld function.

Before she became associated with Greek mythology, she had many similarities with Artemis (wilderness, and watching over wedding ceremonies) and Hera (child rearing and the protection of young men or heroes, and watching over wedding ceremonies).

Epithets

- Chthonian (Earth/Underworld goddess)

- Enodia (Goddess of the paths)

- Antania (Enemy of mankind)

- Artemis of the crossroads

- Phosphoros (the light-bringer)

- Soteira ("Saviour")

- Trioditis (gr.) Trivia (latin: Goddess of Three Roads)

- Klêidouchos (Keeper of the Keys)

- Tricephalus or Triceps (The Three-Headed)[11]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Walter Burkert, (1987) Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical, pp 171. Oxford, Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-15624-0.

- ↑ Kraus 1960:12.

- ↑ These associations were especially prominent in rural areas. See: Mikalson, 215, 217.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Johnston, Sarah Iles, (1991). Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece. ISBN 0-520-21707-1

- ↑ Lewis Richard Farnell, (1896). "Hecate in Art", The Cults of the Greek States. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- ↑ Pausanius, Description of Greece ii.22.7, W. H. S. Jones translation accessible online at theoi.com. Retrieved June 23, 2007. See also: Gantz, 27.

- ↑ For an excellent overview of the evolution of Hecate in sculpture, see Charles M. Edwards, "The Running Maiden from Eleusis and the Early Classical Image of Hekate," American Journal of Archaeology, Volume 90(3), (July 1986). 307-318.

- ↑ Kraus 1960.

- ↑ Strabo, Geography xiv.2.25; Kraus 1960.

- ↑ Strabo, Geography, xiv.1.23

- ↑ For an excellent listing of poetic and cultic epithets, see theoi.com. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Primary sources

- * Apollodorus. Gods & Heroes of the Greeks. Translated and with an Introduction and Notes by Michael Simpson. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1977. ISBN 0-87023-205-3.

- Hesiod, Theogony, Works and Days. An English translation is available online

- Pausanias, Description of Greece.

- Strabo, Geography

Secondary sources

- Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical. Translated by John Raffan. Oxford: Blackwell, 1985. ISBN 0631112413.

- Berg, William. "Hecate: Greek or 'Anatolian'?" Numen, Volume 21 (Fasc. 2) (August 1974). 128-140.

- Dillon, Matthew. Pilgrims and Pilgrimage in Ancient Greece. London; New York: Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0415127750.

- Farnell, Lewis Richard. The Cults of the Greek States (in Five Volumes). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1907.

- Farnell, Lewis Richard. "Hecate in Art", The Cults of the Greek States. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1896.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles. Hekate Soteira: A Study of Hekate's Role in the Chaldean Oracles and Related Literature. An American Philological Association Book: 1990. ISBN 1555404278.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles. Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece. University of California Press: 1991. ISBN 0-520-21707-1

- Kerenyi, Karl. The Gods of the Greeks. London & New York: Thames and Hudson, 1951. ISBN 0500270481.

- Mikalson, Jon D. Ancient Greek Religion. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005. ISBN 0631232222.

- Parke, H. W. Festivals of the Athenians. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977. ISBN 0-8014-1054-1.

- Powell, Barry B. Classical Myth (Second Edition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1998. ISBN 0-13-716714-8.

- Rose, H. J. A Handbook of Greek Mythology. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1959. ISBN 0-525-47041-7.

- Ruickbie, Leo. Witchcraft Out of the Shadows: A Complete History. Robert Hale, 2004. ISBN 0709075677.

- Salmonson, Jessica Amanda. The Encyclopedia of Amazons. Paragon House, 1991. ISBN 1557784205.

- Vol, Mary. "Athene (Athena) and Artemis" in Seppo Sakari Telenius' Athena-Artemis. Helsinki: Kirja kerrallaan, 2005 and 2006. ISBN 952-92-0560-0.

- Ventris, Michael & Chadwick, John. Documents in Mycenaean Greek (Second Edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973. ISBN 0521085586.

External links

- Myths of the Greek Goddess Hecate

- Frequently Asked Questions about Hekate

- Encyclopaedia Britanica 1911: "Hecate"

- Hekate: Guardian at the Gate

- Theoi Project, Hecate classical literary sources and art

- Hecate in Early Greek Religion

- Hekate in Greek esotericism: Ptolemaic and Gnostic transformations of Hecate

- cast of the Crannon statue, at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.