Difference between revisions of "Hasidism" - New World Encyclopedia

| (62 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ready}}{{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{ready}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}} |

| + | [[File:Boyan tish, Sukkot 2009.jpg|thumb|400px|A ''[[Tish (Hasidic celebration)|tish]]'' of the Boyan [[Hasidic dynasty]] in [[Jerusalem]], holiday of [[Sukkot]], 2009.]] | ||

| + | '''Hasidic Judaism''' (also ''Chasidic,'' among others, from the [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]]: חסידות Chassidus, meaning "piety") is a [[Haredi Judaism|Haredi]] [[Judaism|Jewish]] religious movement that originated in [[Eastern Europe]] in the eighteenth century. The hasidic tradition represents a constant striving for an intimate give-and-take relationship with [[God]] in every moment of human life. | ||

| − | [[ | + | Founded by [[Rabbi]] [[Israel ben Eliezer]] (1698–1760), also known as the ''[[Ba'al Shem Tov]],'' Hasidism emerged when European Jews had grown disillusioned as a result of the failed messianism of the past century and the dryness of contemporary rabbinic Judaism, which focused on strictly limited [[Talmud]]ic studies. Many felt that Jewish life had turned anti-mystical and had become too academic, lacking any emphasis on [[spirituality]] or joy. For the ''Hasidim,'' the ''Ba'al Shem Tov'' corrected this situation. |

| − | |||

| − | + | In its initial stages, Hasidism met with strong opposition from contemporary rabbinical leaders, most notably the [[Vilna Gaon]], leader of the [[Lithuanian Jews]]. After the Baal Shem Tov's death, Hasidism developed into a number of "dynasties," centered on leading rabbinical families, many of which have continued to this day. | |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | + | After experiencing a crisis during the persecutions of the [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] and [[Nazism|Nazi]] regimes, Hasidism today is once again a fast growing movement, especially in the U.S. and Israel, due to its tradition of having large families and, among some sects, of reaching out to other Jews in search of their traditional roots. | |

==History== | ==History== | ||

===Background=== | ===Background=== | ||

| − | [[Image:Rzeczpospolita.png|thumb| | + | [[Image:Rzeczpospolita.png|thumb|400px|Greater Poland in the mid-seventeenth century]] |

| − | In greater [[Poland]], where the bulk of European Jewry had established itself since the | + | In greater [[Poland]], where the bulk of European Jewry had established itself since the 1200s, a struggle between traditional [[Rabbinic Judaism]] and radical [[Kabbalah|kabbalistic]] [[mysticism]] became particularly acute after the messianic movement of [[Sabbatai Zevi]] in the seventeenth century. |

| − | + | Earlier, mystical doctrines and sectarianism showed themselves prominently among the Jews of the southeastern provinces, while in the [[Lithuania]]n provinces, rabbinical orthodoxy held sway. In part, this division in modes of thought reflected social differences between the northern (Lithuanian) Jews and the southern Jews of [[Ukraine]]. In Lithuania, the Jewish masses mainly lived in densely-populated towns where rabbinical academic culture flourished, while in Ukraine the Jews tended to live scattered in villages far removed from intellectual centers. | |

| − | Besides these influences, many Jews had grown discontented with traditional [[Rabbinic Judaism]] and | + | Pessimism became intense in the south after the [[Chmielnicki Uprising|Cossacks' Uprising]] (1648-1654) under [[Bohdan Khmelnytsky]] and the turbulent times in Poland (1648-1660), which decimated the Jewry of Ukraine, but left the Jews of Lithuania comparatively untouched. After the Polish magnates regained control of southern Ukraine in the last decade of the seventeenth century, an economic renaissance ensued. The magnates began a massive rebuilding and re-population effort adopting a generally benevolent attitude towards the Jews. |

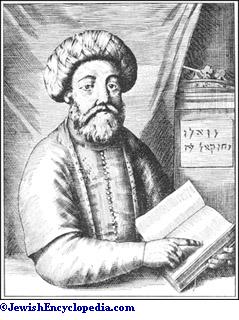

| + | [[Image:Shabbatai1.jpg|thumb|left|150300px|Shabbetai Zevi]] | ||

| + | Besides these influences, many Jews had grown discontented with traditional [[Rabbinic Judaism]] and had gravitated toward [[mysticism]]. In this ripe environment, the messianic claims of [[Shabbetai Zevi]] found fertile soil, creating a wave of mystically-enhanced optimism that refused to die even after his own defection to [[Islam]] and death in 1676. Talmudic traditionalists gained the upper hand in the later seventeenth century, but did not succeed in totally suppressing either outright [[superstition]] or fascination with the potential of the [[Kabbalah]] as a channel for mystical insight. | ||

| − | + | The religious formalism of conservative [[rabbi]]s thus did not provide a satisfactory religious experience for many [[Jews]], some of whose older relatives had been persecuted by traditionalist authorities in the wake of the tragic failure of [[Shabbetai Zevi]] and the later specter of [[Jacob Frank]]'s [[antinomianism]]. Although traditional [[Judaism]] had adopted some features of [[Kabbalah]], it adapted them in a way that many felt overemphasized the external forms of [[fasting]], [[penance]], and spiritual sadness, without giving due emphasis to mystical experience, personal relationship with [[God]], and joy. | |

| − | Hasidism provided a ready response to the desire of the common people in its simple, stimulating, and comforting faith. Early Hasidism aimed not at dogmatic or ritual reform, but at a psychological change within the believer. | + | Hasidism provided a ready response to the desire of the common people in its simple, stimulating, and comforting faith. Early Hasidism aimed not at dogmatic or ritual reform, but at a psychological change within the believer. Its goal was the creation a new type of Jew, who was infused with an infectious love for God and his fellow man, placing emotion above reason and ritual, and exaltation above mere religious knowledge. |

| − | === | + | ===The Ba'al Shem Tov=== |

| − | + | The founder of Hasidism was [[Israel ben Eliezer]], also known as the ''Ba'al Shem Tov''—the "Master of the Good Name"—abbreviated as the ''Besht''. His fame as a healer and prognosticator spread not only among the Jews, but also among the non-Jewish peasants and the Polish nobles. | |

| − | The founder of Hasidism | ||

| − | To the common people, the ''Besht'' appeared wholly admirable. Characterized by an extraordinary sincerity and simplicity, he | + | To the common people, the ''Besht'' appeared wholly admirable. Characterized by an extraordinary sincerity and simplicity, he taught that true religion consisted not primarily of [[Talmud]]ic scholarship, but of a sincere love of God combined with warm faith and belief in the efficacy of [[prayer]]. He held that the ordinary person, filled with a sincere belief in God, is more acceptable to God than someone versed in the Talmud and fully observant of [[halkha|Jewish law]] but who lacks inspiration in his attendance to the divine. This democratization of Jewish tradition attracted not only the common people, but also numerous scholars who were dissatisfied with the current rabbinical [[scholasticism]] and ascetic kabbalistic traditions. |

| − | + | In about 1740, the ''Besht'' established himself in the [[Podolia]]n town of [[Medzhybizh|Mezhbizh]]. He gathered about him numerous disciples and followers, whom he initiated not by systematic intellectual exposition, but by means of sayings and [[parable]]s. These contained both easily graspable spiritual and moral teachings for the laymen, and profound kabbalistic insights for the scholars. His sayings spread by oral transmission and were later written down by his disciples. | |

===The spread of Hasidism=== | ===The spread of Hasidism=== | ||

| − | The [[Ba'al Shem Tov]]'s disciples attracted many followers. They themselves established numerous Hasidic schools and [[halakah|halakic]] [[beth din|courts]] across [[Europe]]. After the ''Besht'''s death, followers continued his cause, notably under the leadership of | + | The [[Ba'al Shem Tov]]'s disciples attracted many followers. They themselves established numerous Hasidic schools and [[halakah|halakic]] [[beth din|courts]] across [[Europe]]. After the ''Besht'''s death, followers continued his cause, notably under the leadership of Rabbi [[Dovber of Mezeritch|Dov Ber of Mezeritch]], known as the ''[[Maggid]]''. His students, in turn, attracted many more Jews to Hasidism. |

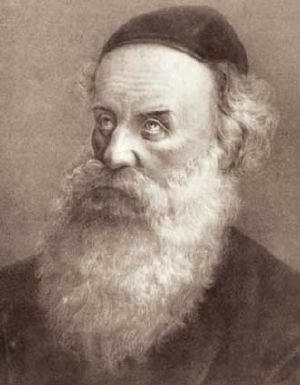

| + | [[Image:Schneur Zalman of Liadi.jpg|thumb|300px|Schneur Zalman of Liadi, founder of Chabad Hasidism.]] | ||

After Dov Ber's death, his inner circle of followers, known as the "Chevraya Kadisha," the Holy Fellowship, agreed to divide up the whole of Europe into different territories, and have each one charged with disseminating hasidic teachings in his designated area. Hasidic Judaism eventually became the way of life of the majority of Jews in [[Ukraine]], [[Galicia (Central Europe)|Galicia]], [[Belarus]], and central [[Poland]]. The movement also had sizable groups of followers in [[Hungary]]. | After Dov Ber's death, his inner circle of followers, known as the "Chevraya Kadisha," the Holy Fellowship, agreed to divide up the whole of Europe into different territories, and have each one charged with disseminating hasidic teachings in his designated area. Hasidic Judaism eventually became the way of life of the majority of Jews in [[Ukraine]], [[Galicia (Central Europe)|Galicia]], [[Belarus]], and central [[Poland]]. The movement also had sizable groups of followers in [[Hungary]]. | ||

| − | [[ | + | Hasidism gradually branched out into two main divisions: 1) In Ukraine and in Galicia and 2) in Greater Lithuania. The disciples, [[Elimelech of Lizhensk]] and the grandson of the ''Besht,'' Boruch of [[Medzhibozh (Hasidic dynasty)|Mezhbizh]], directed the first of these divisions. Lithuanian Hasidim, meanwhile, generally followed Rabbi [[Shneur Zalman]] of Liadi, the founder of [[Chabad Lubavitch|Chabad]] Hasidism, and Rabbi [[Aharon of Karlin]]. Shneur Zalman's lineage became well known in the United States through the outreach programs of the Chabad Lubavitch movement and the leadership of [[Menachem Mendel Schneerson]], the seventh ''[[Rebbe]]'' of the dynasty. |

| − | + | Elimelech of Lizhensk affirmed belief in what became known as ''[[tzaddikism]]'' as a fundamental doctrine of Hasidism. In his book, ''No'am Elimelekh,'' he conveys the idea of the ''[[tzadik]]'' ("righteous one") as the charismatic mediator between God and the common people. | |

| + | |||

| + | ===Opposition=== | ||

| + | Early on in this history, a serious [[schism]] evolved between the hasidic and non-hasidic Jews. Those [[Europe]]an [[Jew]]s who rejected the hasidic movement dubbed themselves ''[[misnagdim]]'' (literally, "opponents"). Among their criticism were the following: | ||

| − | + | * Hasidism had novel emphasis on unusual aspects of [[halakha|Jewish law]] and failed to give due respect to Talmudic study in general. | |

| + | * The overwhelming exuberance of hasidic worship was disturbing. | ||

| + | * Hasidic ascriptions of [[infallibility]] and [[miracle]]-working to their leaders was an unacceptable substitution of human leadership in place of God. | ||

| + | * Hasidism was vulnerable to dangerous messianic impulses such as had occurred in the earlier cases of [[Shabbatai Zevi]] and [[Jacob Frank]]. | ||

| − | + | The ''misnagdim'' also denounced Hasidism's growing literature expressing the legend of the Ba'al Shem Tov, and criticized their way of dress as overly pious in external appearance while lacking internal humility. The hasidic notion that God permeates all of creation was opposed on grounds that it constituted [[pantheism]], a violation of the [[Maimonides|Maimonidean]] principle that God is in no sense physical. Many critics also considered as dangerous the hasidic teaching, based on the [[Kabbalah]], that there are sparks of goodness in all things, which can be redeemed to perfect the world. Some ''misnagdim'' also denigrated the Hasidim for their lack of Jewish scholarship. | |

| − | + | At one point the followers of Hasidism were put under the ''[[cherem]]'' (the Jewish form of communal [[excommunication]]) by a group of traditionalist rabbis. After years of bitter acrimony, a reconciliation took place in response to the perceived greater threat of the ''[[Haskala]],'' or Jewish Enlightenment. Despite this, a degree of distrust between the various sects of Hasidism and other [[Orthodox Judaism|Orthodox Jews]] has continued through the present day. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Emigration and persecution=== | |

| − | + | While continuing to grow in Eastern Europe, Hasidic Judaism also came to [[Western Europe]] and then to the [[United States]] during the large waves of Jewish emigration in the 1880s. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The [[Bolshevik]] revolution and the rise of [[Communism]] saw the disintegration of important hasidic centers in Eastern Europe, such as [[Chabad]], [[Breslov]], [[Chernobyl]], and [[Ruzhin]]. Nevertheless, many Hasidim, primarily those following the Chabad school, remained in the Soviet Union, primarily in Russia, intent on preserving [[Judaism]] as a religion in the face of increasing Soviet opposition. | |

| − | + | With ''[[Yeshiva|yeshivas]]'' and and even private religious instruction in Hebrew outlawed, synagogues seized by the government and transformed into secular community centers, and religious [[circumcision]] forbidden to all members of the [[Communist Party]], most Soviet Hasidim took part in the general Jewish religious underground movement. Many became so-called "wandering clerics," traveling from village to village wherever their services were needed. These figures were often imprisoned and sometimes executed. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The [[Holocaust]] brought final destruction to all hasidic centers of Eastern [[Europe]], and countless Hasidim, who rarely hid their identities, perished. The survivors eventually moved either to [[Israel]] or to [[United States of America|America]] and established new centers of Hasidic Judaism modeled after their original communities. | |

| − | === | + | ===Today's communities=== |

| − | [[ | + | Some of the larger and more well-known chasidic sects that still exist include [[Belz (Hasidic dynasty)|Belz]], [[Bobov (Hasidic dynasty)|Bobov]], [[Breslov (Hasidic dynasty)|Breslov]], [[Ger (Hasidic dynasty)|Ger]], [[Chabad|Lubavitch (Chabad)]], [[Munkacs (Hasidic dynasty)|Munkacs]], [[Puppa (Hasidic dynasty)|Puppa]], [[Klausenburg (Hasidic dynasty)|Sanz (Klausenburg)]], [[Satmar (Hasidic dynasty)|Satmar]], [[Skver (Hasidic dynasty)|Skver]], [[Spinka (Hasidic dynasty)|Spinka]], and [[Vizhnitz (Hasidic dynasty)|Vizhnitz]]. |

| − | |||

| − | + | The largest groups in Israel today are Ger, Chabad, Belz, Satmar, Breslov, Vizhnitz, Seret-Vizhnitz, Nadvorna, and Toldos Aharon. In the [[United States]] the largest are [[Lubavitch]], [[Satmar]] and [[Bobov]], all centered in [[Brooklyn]], and [[Rockland County, New York|Rockland County]], New York. Large hasidic communities also exist in the [[Montreal]] borough of [[Outremont]]; [[Toronto]]; [[London]]; [[Antwerp]]; [[Melbourne]]; the [[Fairfax District, Los Angeles, California|Fairfax]] and other neighborhoods of [[Los Angeles]]; and [[St. Louis Park, Minnesota|St. Louis Park]], a Minneapolis suburb. | |

| − | + | Hasidism today is a healthy and growing branch of [[Orthodox Judaism]], with some hasidic groups attracting many new members, as secularized Jews seek to return to their religious roots. Even without new converts, its numbers are multiplying rapidly due its tradition of marrying young and having large families. | |

==Religious practice and culture== | ==Religious practice and culture== | ||

===Fundamental conceptions=== | ===Fundamental conceptions=== | ||

| − | The teachings of Hasidism are founded on two theoretical conceptions: 1) | + | The teachings of Hasidism are founded on two theoretical conceptions: 1) Religious [[panentheism]], or the omnipresence of [[God]], and 2) the idea of ''[[Devekut|Devekus]],'' communion between God and man. |

| − | "Man," says the ''Besht'', "must always bear in mind that God is omnipresent and is always with | + | "Man," says the ''Besht'', "must always bear in mind that [[God]] is omnipresent and is always with him… Let man realize that when he is looking at material things he is in reality gazing at the image of the [[Deity]] which is present in all things. With this in mind man will always serve God even in small matters." |

| − | + | ''Deveikus'' (communion) refers to the belief that an unbroken intercourse takes place between the world of God and the world of humanity. It is true not only that the Deity influences the acts of man, but also that man exerts an influence on the will of God. Indeed, every act and word of man produces a corresponding vibration in the upper spheres. Communion with God for the purpose of uniting with the source of life and of influencing it is the chief practical principle of Hasidism. This communion is achieved through the concentration of all thoughts on God, and consulting Him in all the affairs of life. | |

| − | + | The righteous man is in constant communion with God, even in his worldly affairs, since here also he feels His presence. However, a special form of communion with God is [[prayer]]. In order to render this communion complete the prayer must be full of fervor, even ecstatic. Even seemingly mechanical means, such as violent swaying, shouting, and singing may be employed to these ends. | |

| − | + | According to the [[Ba'al Shem Tov]], the essence of religion is in sentiment and not in reason. Theological learning and [[halakha|halakhic lore]] are of secondary importance. In the performance of religious rites, the mood of the believer is of more importance than the externals. For this reason formalism and concentration on superfluous ceremonial details can even be injurious. | |

| − | |||

| − | According to the Ba'al Shem Tov, the essence of religion is in sentiment and not in reason. Theological learning and [[halakha|halakhic lore]] are of secondary importance. In the performance of religious rites, the mood of the believer is of more importance than the externals. For this reason formalism and concentration on superfluous ceremonial details can even be injurious. | ||

===Hasidic philosophy=== | ===Hasidic philosophy=== | ||

| + | Hasidic philosophy teaches a method of contemplating on God, as well as the inner significance of the ''[[mitzvo]]s'' (commandments and rituals of Torah law). Hasidic philosophy generally has four main goals: | ||

| − | + | *'''Revival:''' At the time when the [[Ba'al Shem Tov]] founded Hasidism, the Jews had been physically crushed by massacres—in particular, those of the Cossack leader [[Chmelnitzki]] in 1648-1649—and poverty, as well as being spiritually crushed by the disappointment engendered by the false [[messiah]]s. Hasidism thus had the mission to revive the [[Jews]] both physically and spiritually. It focused on helping Jews establish themselves financially, and also uplifting their moral and religious lives through its teachings. | |

| − | |||

| − | *'''Revival''' | ||

| − | *'''Piety''' | + | *'''Piety:''' A Hasid, in classic [[Torah]] literature, refers to a person of piety beyond the letter of the law. Hasidism aims at cultivating this extra degree of piety. |

| − | *'''Refinement''' | + | *'''Refinement:''' Hasidism teaches that one should not merely strive to improve one's character by learning new habits and manners. Rather a person should completely change the quality, depth, and maturity of one's nature. This change is accomplished by internalizing and integrating the perspective of hasidic philosophy. |

| − | *'''Demystification''' | + | *'''Demystification:''' Hasidism seeks to make the esoteric teachings of [[Kabbalah]] understandable to every [[Jew]], regardless of educational level. This understanding is meant to help refine the person, as well as adding depth and vigor to one's ritual observance. |

===Liturgy and prayer=== | ===Liturgy and prayer=== | ||

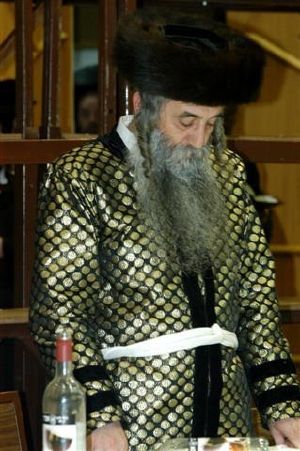

| − | + | [[Image:TosherRebbe.JPG|thumb|300px|The [[Tosh (Hasidic dynasty)|Tosher]] [[Rebbe]] concentrating on prayer]] | |

| − | [[Image:TosherRebbe.JPG|thumb| | + | Most Hasidim pray according to one of the variations of the prayer book tradition known as ''[[Nusach Sefard]],'' a blend of [[Ashkenazi]] and [[Sephardi]] liturgies based on the kabbalistic innovations of Rabbi [[Isaac Luria]]. However, several Hasidic dynasties have their own specific adaptation of ''Nusach Sefard''. |

| − | Most Hasidim pray according to one of the variations of the prayer book tradition known as ''[[Nusach Sefard]]'' | ||

| − | The | + | The [[Ba'al Shem Tov]] is believed to have introduced two innovations to the Friday services: The recitation of Psalm 107 before the afternoon service, as a prelude to the Sabbath, and Psalm 23 just before the end of evening service. |

Many Hasidim pray in [[Ashkenazi Hebrew]]. This dialect happens to be the Yiddish dialect of the places from which most Hasidim originally came. There are significant differences between the dialects used by Hasidim originating from other places. | Many Hasidim pray in [[Ashkenazi Hebrew]]. This dialect happens to be the Yiddish dialect of the places from which most Hasidim originally came. There are significant differences between the dialects used by Hasidim originating from other places. | ||

| − | Hasidic prayer has a distinctive accompaniment of wordless melodies called ''[[nigun]]im'' that represent the overall mood of the prayer. In recent years this innovation has become increasingly popular in non- | + | Hasidic prayer has a distinctive accompaniment of wordless melodies called ''[[nigun]]im'' that represent the overall mood of the prayer. In recent years this innovation has become increasingly popular in non-hasidic communities as well. Hasidic prayer also has a reputation for taking a very long time, although some groups do pray quickly. Hasidic tradition regards prayer as one of the most paramount activities during the day. |

Many male [[Orthodox Judaism|Orthodox]] [[Jew]]s customarily immerse in a ''[[mikvah]]'' (ritual pool of water) before major [[Jewish holiday]]s (and particularly before [[Yom Kippur]]), in order to achieve spiritual cleanliness. Hasidim have extended this to a daily practice preceding morning prayers. | Many male [[Orthodox Judaism|Orthodox]] [[Jew]]s customarily immerse in a ''[[mikvah]]'' (ritual pool of water) before major [[Jewish holiday]]s (and particularly before [[Yom Kippur]]), in order to achieve spiritual cleanliness. Hasidim have extended this to a daily practice preceding morning prayers. | ||

===Dress=== | ===Dress=== | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Dombrovnadvorna.jpg|thumb|400px|Dombrover Rebbe of Monsey with the Nadvorna Rebbe and others]] | |

| − | + | [[Image:IMG 6982.JPG|thumb|300px|Rabbi Moshe Leib Rabinovich, Munkacser Rebbe, wearing a ''kolpik'']] | |

| − | + | [[Image:young_hasid.jpg|300px|thumb|right|Young Hasid age 22.]] | |

| − | + | Hasidim are also noted for their distinctive attire. Many details of their dress are shared by other [[Haredi Judaism|Haredi]], or strictly Orthodox, Jews. In additional, within the hasidic world, one can distinguish different groups by subtle differences in appearance. Much of hasidic dress was originally simply the traditional clothing of all Eastern European Jews, but Hasidim have preserved many of these styles to the present day. Furthermore, Hasidim have attributed mystical intents to these clothing styles. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Image: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Hasidim button their clothes right over left. Most do not wear neck-ties. Hasidic men most commonly wear suits in dark colors with distinctively long jackets, called ''[[rekel]]ekh''. On the [[Sabbath]] they wear a long black [[satin]] or [[polyester]] robe called a ''zaydene kapote'' or ''[[bekishe]]''. On [[Yom Tov|Jewish Holy Days]] a silk garment may be worn. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | Hasidim customarily wear black hats during the weekdays as do nearly all Haredim today. A variety of hats are worn depending on the sect. Hasidim also wear a variety of fur headdresses on the Sabbath: |

| + | *''[[Shtreimel]]''—a fur hat worn by most Hasidim today, including those from Galicia and Hungary such as the [[Satmar]], [[Munkacs]], [[Bobov (Hasidic dynasty)|Bobov]], [[Breslov (Hasidic dynasty)|Breslov]], and [[Belz (Hasidic dynasty)|Belz]], and some non-Galician Polish Hasidim, such as [[Biala (Hasidic dynasty)|Biala]], as well as some non-Hasidic Haredim in Jerusalem. | ||

| + | *''[[Spodik]]''—name given to the ''shtreimel'' worn by Polish Hasidim such as [[Ger (Hasidic dynasty)|Ger]], [[Amshinov (Hasidic dynasty)|Amshinov]], [[Osrov-Henzin (Hasidic dynasty)|Ozharov]], [[Aleksander (Hasidic dynasty)|Aleksander]]. | ||

| + | *''[[Kolpik]]''—a traditional Slavic headdress, worn by unmarried sons and grandsons of many ''rebbes'' on the Sabbath. The ''kolpik'' is also worn by some rebbes themselves on special occasions. | ||

| + | *Black felt [[fedora (hat)|fedora]]s—worn by Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidim dating back to the style of the 1940s and 50s. They are the same as the hats worn by many non-Hasidic Haredim. | ||

| + | *''Shtofener''—Various forms of felt open crown hats. Affiliation can sometimes be identified by whether there is a pinch in the middle of the top or not, as well as the type of brim. Many Satmar laymen wear a type of open crown hat that resembles a [[bowler hat]] with rounded edges on the brim. | ||

| + | *''Samet'' ([[velvet]]) or ''biber'' ([[beaver]])—Hats worn by Galician and Hungarian Hasidim. There are many types of ''samet'' hats, most notably the "high" and "flat" varieties. The "flat" type is worn by Satmar Hasidim and some others. They are called beaver hats even though today they are usually made from [[rabbit]]. | ||

| + | *''Kutchma''—A small fur hat worn by many Hasidic laymen during weekdays in the winter. Today this hat is sometimes made from cheaper materials, such as polyester. This hat is referred to as a ''shlyapka'' (шляпка), by Russian Jews. | ||

=== Other distinct clothing === | === Other distinct clothing === | ||

| − | Many Hasidim traditionally do not wear wristwatches | + | Many, though not all, Hasidim traditionally do not wear wristwatches but instead use a watch and chain and a vest (also right-over-left). There are also various traditions regarding socks, breeches, shoes or boots, and suit styles. |

| − | + | ====Hair==== | |

| − | [[ | + | [[Image:HasidicRebbe.jpg|thumb|300px|The Dorohoi [[Rebbe]] in his traditional rabbinical [[Shabbat|Sabbath]] garb]] |

| − | + | Following a biblical commandment not to shave the sides of one's face, male members of most Hasidic groups wear long, uncut sideburns called [[payot]]h ([[Ashkenazi Hebrew]] ''peyos,'' [[Yiddish language|Yiddish]] ''peyes''). Many Hasidim shave off the rest of their hair on the top of their head. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Not every hasidic group requires long ''peyos,'' and not all Jewish men with ''peyos'' are Hasidic, but all Hasidic groups discourage the shaving of one's beard, although some hasidic laymen ignore this dictum. Hasidic boys generally receive their [[first haircut]]s ceremonially at the age of three years. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

====Tzitzit==== | ====Tzitzit==== | ||

| − | + | The white threads seen at the waists of Hasidim and other Orthodox Jewish males are called ''[[tzitzit]]''. The requirement to wear fringes comes from the [[Book of Numbers]]: "Speak to the children of Israel, and bid them that they make them fringes on the borders of their garments throughout their generations" (Numbers 15:38). In order to fulfill this commandment, Orthodox males wear a ''talles katan,'' a square white garment with the fringes at the corners. By tradition, a hasidic boy will receive his first fringed garment on his third birthday, the same day as his first haircut. Most Orthodox Jews wear the ''talles katan'' under their shirts, where it is unnoticeable except for the strings that many leave hanging out. Many Hasidim, as well as some other Haredim, wear the ''talles katan'' over their shirt instead. | |

| − | The white threads seen at the waists of Hasidim and other Orthodox Jewish males | ||

| − | + | ==Women and families== | |

| − | Hasidic | + | [[Image:Hasidic-family.jpg|thumb|right|400px|Hasidic family]] |

| + | As with other traditions of [[Orthodox Judaism]], hasidic women may not be ordained to teach men, lead religious services, or otherwise assume positions of community leadership except among other women. In common with all Haredim, Hasidic men will not touch or even shake hands with anyone of the opposite sex other than their wife, mother, or female offspring. The converse applies for women. | ||

| − | + | Hasidic women wear clothing of less distinctive appearance than that of their male counterparts, but which answers to the principles of ''[[tzeniut]]''—modest dress—in the sense of Jewish law. As with all Haredi women, the standard is long, conservative skirts, and sleeves past the elbow. Otherwise, female Hasidic fashion remains on the conservative side of secular women's fashion. Most Hasidic women do not wear red clothing. | |

| − | In keeping with [[halacha|Jewish law]] married Hasidic women cover their hair. In many Hasidic groups the women wear wigs for this purpose. In some of these groups the women might also wear a ''tichel'' (scarf) or hat on top of the wig either on a regular basis or when attending services or other religious events. Other groups consider wigs too natural looking, so they simply put their hair into kerchiefs | + | In keeping with [[halacha|Jewish law]] married Hasidic women cover their hair. In many Hasidic groups the women wear wigs for this purpose. In some of these groups the women might also wear a ''tichel'' (scarf) or hat on top of the wig either on a regular basis or when attending services or other religious events. Other groups consider wigs too natural looking, so they simply put their hair into kerchiefs. In some groups, such as [[Satmar]], married women are expected to shave their heads and wear head kerchiefs. Hasidim allow uncovered hair for women before marriage. |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Image:Hasidic-wedding.jpg|thumb|300px|Hasidic wedding in Jerusalem]] | |

| − | |||

| − | Hasidic | ||

| − | + | Hasidic men and women, as customary in [[Haredi Judaism]], usually meet through matchmakers in a process called a ''[[shidduch]],'' but marriages involve the mutual consent of both the couple and of the parents. Bride and groom are expected to be about the same age. Marriage age ranges from 17-25, with 18-21 considered the norm. | |

| − | Hasidic | + | Hasidic thought emphasized the holiness of [[sexual intercourse|sex]], and the Jewish religion stresses the importance of married couples enjoying the pleasure of sexual intercourse as a divine command. Many pious Hasidic couples thus follow strict regulations regarding what types of sexual relations are allowed and what positions etc. They also follow the general [[halkha|halakhic]] customs regarding ritual purification and refrain from sexual relations during a woman's menstrual cycle. |

| − | + | Hasidic Jews, like many other Orthodox Jews, produce large families. Many sects follow this custom out of what they consider a biblical mandate to 'be fruitful and multiply. The average chasidic family in the United States has 7.9 children.<ref>Jack Wertheimer, | |

| − | + | [https://www.aish.com/jw/s/48899452.html Jews and the Jewish Birthrate] ''Aish''. Retrieved December 24, 2021.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Languages== | |

| + | Most Hasidim speak the language of their countries of residence, but use [[Yiddish]] among themselves as a way of remaining distinct and preserving tradition. Thus hasidic children are still learning Yiddish today, one of the major factors in keeping the language alive since modern [[Hebrew]] was adopted in [[Israel]]. Yiddish newspapers are still published in hasidic communities, and Yiddish fiction is also being written, primarily aimed at hasidic women. Films in Yiddish are also produced within the Hasidic community and released immediately as DVDs. | ||

| − | + | Some Hasidic groups actively oppose the everyday use of [[Hebrew]], which is considered a holy tongue appropriate more for liturgical use, prayer, and scripture reading. Hence Yiddish is the vernacular and common tongue for Hasidim around the world. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | == | ||

| − | <references /> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | *Altshuler, Mor. ''The Messianic Secret of Hasidism''. Brill's series in Jewish studies, v. 39. Leiden: Brill, 2006. ISBN 9789004153561. | |

| − | * | + | *Buber, Martin. ''Tales of the Hasidim''. New York: Schocken Books, 1991. ISBN 9780805209952. |

| − | + | *Elior, Rachel. ''The Mystical Origins of Hasidism''. Oxford: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2006. ISBN 9781904113041. | |

| − | + | *Heschel, Abraham Joshua, and Samuel H. Dresner. ''The Circle of the Baal Shem Tov: Studies in Hasidism''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985. ISBN 9780226329604. | |

| − | + | *Lamm, Norman. ''The Religious Thought of Hasidism: Text and Commentary''. Sources and studies in Kabbalah, Hasidism, and Jewish thought, v. 4. New York: Michael Scharf Publication Trust of Yeshiva University Press, 1999. ISBN 9780881254402. | |

| − | + | *Rabinowicz, Tzvi. ''The Encyclopedia of Hasidism''. Northvale, N.J.: Jason Aronson, 1996. ISBN 9781568211237. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | *'' | ||

| − | *'' | ||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | *[http:// | + | All links retrieved December 24, 2021. |

| − | *[http://www. | + | *[http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=349&letter=H Hasidim, Hasidism] ''Jewish Encyclopedia'' |

| − | + | *[http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Judaism/Hasidism.html Orthodox Judaism: Hasidism] ''Jewish Virtual Library'' | |

| − | *[http://www. | + | *[http://www.chabad.org/library/article.asp?AID=109854 Chassidic Texts] |

| − | + | *[http://www.nishmas.org/htmldocs/stories.html Archives of Chassidic Stories] | |

| − | |||

| − | *[http://www. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:philosophy and religion]] | [[Category:philosophy and religion]] | ||

[[Category:religion]] | [[Category:religion]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Judaism]] | ||

{{credits|163589758}} | {{credits|163589758}} | ||

Latest revision as of 08:41, 20 January 2024

Hasidic Judaism (also Chasidic, among others, from the Hebrew: חסידות Chassidus, meaning "piety") is a Haredi Jewish religious movement that originated in Eastern Europe in the eighteenth century. The hasidic tradition represents a constant striving for an intimate give-and-take relationship with God in every moment of human life.

Founded by Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer (1698–1760), also known as the Ba'al Shem Tov, Hasidism emerged when European Jews had grown disillusioned as a result of the failed messianism of the past century and the dryness of contemporary rabbinic Judaism, which focused on strictly limited Talmudic studies. Many felt that Jewish life had turned anti-mystical and had become too academic, lacking any emphasis on spirituality or joy. For the Hasidim, the Ba'al Shem Tov corrected this situation.

In its initial stages, Hasidism met with strong opposition from contemporary rabbinical leaders, most notably the Vilna Gaon, leader of the Lithuanian Jews. After the Baal Shem Tov's death, Hasidism developed into a number of "dynasties," centered on leading rabbinical families, many of which have continued to this day.

After experiencing a crisis during the persecutions of the Soviet and Nazi regimes, Hasidism today is once again a fast growing movement, especially in the U.S. and Israel, due to its tradition of having large families and, among some sects, of reaching out to other Jews in search of their traditional roots.

History

Background

In greater Poland, where the bulk of European Jewry had established itself since the 1200s, a struggle between traditional Rabbinic Judaism and radical kabbalistic mysticism became particularly acute after the messianic movement of Sabbatai Zevi in the seventeenth century.

Earlier, mystical doctrines and sectarianism showed themselves prominently among the Jews of the southeastern provinces, while in the Lithuanian provinces, rabbinical orthodoxy held sway. In part, this division in modes of thought reflected social differences between the northern (Lithuanian) Jews and the southern Jews of Ukraine. In Lithuania, the Jewish masses mainly lived in densely-populated towns where rabbinical academic culture flourished, while in Ukraine the Jews tended to live scattered in villages far removed from intellectual centers.

Pessimism became intense in the south after the Cossacks' Uprising (1648-1654) under Bohdan Khmelnytsky and the turbulent times in Poland (1648-1660), which decimated the Jewry of Ukraine, but left the Jews of Lithuania comparatively untouched. After the Polish magnates regained control of southern Ukraine in the last decade of the seventeenth century, an economic renaissance ensued. The magnates began a massive rebuilding and re-population effort adopting a generally benevolent attitude towards the Jews.

Besides these influences, many Jews had grown discontented with traditional Rabbinic Judaism and had gravitated toward mysticism. In this ripe environment, the messianic claims of Shabbetai Zevi found fertile soil, creating a wave of mystically-enhanced optimism that refused to die even after his own defection to Islam and death in 1676. Talmudic traditionalists gained the upper hand in the later seventeenth century, but did not succeed in totally suppressing either outright superstition or fascination with the potential of the Kabbalah as a channel for mystical insight.

The religious formalism of conservative rabbis thus did not provide a satisfactory religious experience for many Jews, some of whose older relatives had been persecuted by traditionalist authorities in the wake of the tragic failure of Shabbetai Zevi and the later specter of Jacob Frank's antinomianism. Although traditional Judaism had adopted some features of Kabbalah, it adapted them in a way that many felt overemphasized the external forms of fasting, penance, and spiritual sadness, without giving due emphasis to mystical experience, personal relationship with God, and joy.

Hasidism provided a ready response to the desire of the common people in its simple, stimulating, and comforting faith. Early Hasidism aimed not at dogmatic or ritual reform, but at a psychological change within the believer. Its goal was the creation a new type of Jew, who was infused with an infectious love for God and his fellow man, placing emotion above reason and ritual, and exaltation above mere religious knowledge.

The Ba'al Shem Tov

The founder of Hasidism was Israel ben Eliezer, also known as the Ba'al Shem Tov—the "Master of the Good Name"—abbreviated as the Besht. His fame as a healer and prognosticator spread not only among the Jews, but also among the non-Jewish peasants and the Polish nobles.

To the common people, the Besht appeared wholly admirable. Characterized by an extraordinary sincerity and simplicity, he taught that true religion consisted not primarily of Talmudic scholarship, but of a sincere love of God combined with warm faith and belief in the efficacy of prayer. He held that the ordinary person, filled with a sincere belief in God, is more acceptable to God than someone versed in the Talmud and fully observant of Jewish law but who lacks inspiration in his attendance to the divine. This democratization of Jewish tradition attracted not only the common people, but also numerous scholars who were dissatisfied with the current rabbinical scholasticism and ascetic kabbalistic traditions.

In about 1740, the Besht established himself in the Podolian town of Mezhbizh. He gathered about him numerous disciples and followers, whom he initiated not by systematic intellectual exposition, but by means of sayings and parables. These contained both easily graspable spiritual and moral teachings for the laymen, and profound kabbalistic insights for the scholars. His sayings spread by oral transmission and were later written down by his disciples.

The spread of Hasidism

The Ba'al Shem Tov's disciples attracted many followers. They themselves established numerous Hasidic schools and halakic courts across Europe. After the Besht's death, followers continued his cause, notably under the leadership of Rabbi Dov Ber of Mezeritch, known as the Maggid. His students, in turn, attracted many more Jews to Hasidism.

After Dov Ber's death, his inner circle of followers, known as the "Chevraya Kadisha," the Holy Fellowship, agreed to divide up the whole of Europe into different territories, and have each one charged with disseminating hasidic teachings in his designated area. Hasidic Judaism eventually became the way of life of the majority of Jews in Ukraine, Galicia, Belarus, and central Poland. The movement also had sizable groups of followers in Hungary.

Hasidism gradually branched out into two main divisions: 1) In Ukraine and in Galicia and 2) in Greater Lithuania. The disciples, Elimelech of Lizhensk and the grandson of the Besht, Boruch of Mezhbizh, directed the first of these divisions. Lithuanian Hasidim, meanwhile, generally followed Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, the founder of Chabad Hasidism, and Rabbi Aharon of Karlin. Shneur Zalman's lineage became well known in the United States through the outreach programs of the Chabad Lubavitch movement and the leadership of Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the seventh Rebbe of the dynasty.

Elimelech of Lizhensk affirmed belief in what became known as tzaddikism as a fundamental doctrine of Hasidism. In his book, No'am Elimelekh, he conveys the idea of the tzadik ("righteous one") as the charismatic mediator between God and the common people.

Opposition

Early on in this history, a serious schism evolved between the hasidic and non-hasidic Jews. Those European Jews who rejected the hasidic movement dubbed themselves misnagdim (literally, "opponents"). Among their criticism were the following:

- Hasidism had novel emphasis on unusual aspects of Jewish law and failed to give due respect to Talmudic study in general.

- The overwhelming exuberance of hasidic worship was disturbing.

- Hasidic ascriptions of infallibility and miracle-working to their leaders was an unacceptable substitution of human leadership in place of God.

- Hasidism was vulnerable to dangerous messianic impulses such as had occurred in the earlier cases of Shabbatai Zevi and Jacob Frank.

The misnagdim also denounced Hasidism's growing literature expressing the legend of the Ba'al Shem Tov, and criticized their way of dress as overly pious in external appearance while lacking internal humility. The hasidic notion that God permeates all of creation was opposed on grounds that it constituted pantheism, a violation of the Maimonidean principle that God is in no sense physical. Many critics also considered as dangerous the hasidic teaching, based on the Kabbalah, that there are sparks of goodness in all things, which can be redeemed to perfect the world. Some misnagdim also denigrated the Hasidim for their lack of Jewish scholarship.

At one point the followers of Hasidism were put under the cherem (the Jewish form of communal excommunication) by a group of traditionalist rabbis. After years of bitter acrimony, a reconciliation took place in response to the perceived greater threat of the Haskala, or Jewish Enlightenment. Despite this, a degree of distrust between the various sects of Hasidism and other Orthodox Jews has continued through the present day.

Emigration and persecution

While continuing to grow in Eastern Europe, Hasidic Judaism also came to Western Europe and then to the United States during the large waves of Jewish emigration in the 1880s.

The Bolshevik revolution and the rise of Communism saw the disintegration of important hasidic centers in Eastern Europe, such as Chabad, Breslov, Chernobyl, and Ruzhin. Nevertheless, many Hasidim, primarily those following the Chabad school, remained in the Soviet Union, primarily in Russia, intent on preserving Judaism as a religion in the face of increasing Soviet opposition.

With yeshivas and and even private religious instruction in Hebrew outlawed, synagogues seized by the government and transformed into secular community centers, and religious circumcision forbidden to all members of the Communist Party, most Soviet Hasidim took part in the general Jewish religious underground movement. Many became so-called "wandering clerics," traveling from village to village wherever their services were needed. These figures were often imprisoned and sometimes executed.

The Holocaust brought final destruction to all hasidic centers of Eastern Europe, and countless Hasidim, who rarely hid their identities, perished. The survivors eventually moved either to Israel or to America and established new centers of Hasidic Judaism modeled after their original communities.

Today's communities

Some of the larger and more well-known chasidic sects that still exist include Belz, Bobov, Breslov, Ger, Lubavitch (Chabad), Munkacs, Puppa, Sanz (Klausenburg), Satmar, Skver, Spinka, and Vizhnitz.

The largest groups in Israel today are Ger, Chabad, Belz, Satmar, Breslov, Vizhnitz, Seret-Vizhnitz, Nadvorna, and Toldos Aharon. In the United States the largest are Lubavitch, Satmar and Bobov, all centered in Brooklyn, and Rockland County, New York. Large hasidic communities also exist in the Montreal borough of Outremont; Toronto; London; Antwerp; Melbourne; the Fairfax and other neighborhoods of Los Angeles; and St. Louis Park, a Minneapolis suburb.

Hasidism today is a healthy and growing branch of Orthodox Judaism, with some hasidic groups attracting many new members, as secularized Jews seek to return to their religious roots. Even without new converts, its numbers are multiplying rapidly due its tradition of marrying young and having large families.

Religious practice and culture

Fundamental conceptions

The teachings of Hasidism are founded on two theoretical conceptions: 1) Religious panentheism, or the omnipresence of God, and 2) the idea of Devekus, communion between God and man.

"Man," says the Besht, "must always bear in mind that God is omnipresent and is always with him… Let man realize that when he is looking at material things he is in reality gazing at the image of the Deity which is present in all things. With this in mind man will always serve God even in small matters."

Deveikus (communion) refers to the belief that an unbroken intercourse takes place between the world of God and the world of humanity. It is true not only that the Deity influences the acts of man, but also that man exerts an influence on the will of God. Indeed, every act and word of man produces a corresponding vibration in the upper spheres. Communion with God for the purpose of uniting with the source of life and of influencing it is the chief practical principle of Hasidism. This communion is achieved through the concentration of all thoughts on God, and consulting Him in all the affairs of life.

The righteous man is in constant communion with God, even in his worldly affairs, since here also he feels His presence. However, a special form of communion with God is prayer. In order to render this communion complete the prayer must be full of fervor, even ecstatic. Even seemingly mechanical means, such as violent swaying, shouting, and singing may be employed to these ends.

According to the Ba'al Shem Tov, the essence of religion is in sentiment and not in reason. Theological learning and halakhic lore are of secondary importance. In the performance of religious rites, the mood of the believer is of more importance than the externals. For this reason formalism and concentration on superfluous ceremonial details can even be injurious.

Hasidic philosophy

Hasidic philosophy teaches a method of contemplating on God, as well as the inner significance of the mitzvos (commandments and rituals of Torah law). Hasidic philosophy generally has four main goals:

- Revival: At the time when the Ba'al Shem Tov founded Hasidism, the Jews had been physically crushed by massacres—in particular, those of the Cossack leader Chmelnitzki in 1648-1649—and poverty, as well as being spiritually crushed by the disappointment engendered by the false messiahs. Hasidism thus had the mission to revive the Jews both physically and spiritually. It focused on helping Jews establish themselves financially, and also uplifting their moral and religious lives through its teachings.

- Piety: A Hasid, in classic Torah literature, refers to a person of piety beyond the letter of the law. Hasidism aims at cultivating this extra degree of piety.

- Refinement: Hasidism teaches that one should not merely strive to improve one's character by learning new habits and manners. Rather a person should completely change the quality, depth, and maturity of one's nature. This change is accomplished by internalizing and integrating the perspective of hasidic philosophy.

- Demystification: Hasidism seeks to make the esoteric teachings of Kabbalah understandable to every Jew, regardless of educational level. This understanding is meant to help refine the person, as well as adding depth and vigor to one's ritual observance.

Liturgy and prayer

Most Hasidim pray according to one of the variations of the prayer book tradition known as Nusach Sefard, a blend of Ashkenazi and Sephardi liturgies based on the kabbalistic innovations of Rabbi Isaac Luria. However, several Hasidic dynasties have their own specific adaptation of Nusach Sefard.

The Ba'al Shem Tov is believed to have introduced two innovations to the Friday services: The recitation of Psalm 107 before the afternoon service, as a prelude to the Sabbath, and Psalm 23 just before the end of evening service.

Many Hasidim pray in Ashkenazi Hebrew. This dialect happens to be the Yiddish dialect of the places from which most Hasidim originally came. There are significant differences between the dialects used by Hasidim originating from other places.

Hasidic prayer has a distinctive accompaniment of wordless melodies called nigunim that represent the overall mood of the prayer. In recent years this innovation has become increasingly popular in non-hasidic communities as well. Hasidic prayer also has a reputation for taking a very long time, although some groups do pray quickly. Hasidic tradition regards prayer as one of the most paramount activities during the day.

Many male Orthodox Jews customarily immerse in a mikvah (ritual pool of water) before major Jewish holidays (and particularly before Yom Kippur), in order to achieve spiritual cleanliness. Hasidim have extended this to a daily practice preceding morning prayers.

Dress

Hasidim are also noted for their distinctive attire. Many details of their dress are shared by other Haredi, or strictly Orthodox, Jews. In additional, within the hasidic world, one can distinguish different groups by subtle differences in appearance. Much of hasidic dress was originally simply the traditional clothing of all Eastern European Jews, but Hasidim have preserved many of these styles to the present day. Furthermore, Hasidim have attributed mystical intents to these clothing styles.

Hasidim button their clothes right over left. Most do not wear neck-ties. Hasidic men most commonly wear suits in dark colors with distinctively long jackets, called rekelekh. On the Sabbath they wear a long black satin or polyester robe called a zaydene kapote or bekishe. On Jewish Holy Days a silk garment may be worn.

Hasidim customarily wear black hats during the weekdays as do nearly all Haredim today. A variety of hats are worn depending on the sect. Hasidim also wear a variety of fur headdresses on the Sabbath:

- Shtreimel—a fur hat worn by most Hasidim today, including those from Galicia and Hungary such as the Satmar, Munkacs, Bobov, Breslov, and Belz, and some non-Galician Polish Hasidim, such as Biala, as well as some non-Hasidic Haredim in Jerusalem.

- Spodik—name given to the shtreimel worn by Polish Hasidim such as Ger, Amshinov, Ozharov, Aleksander.

- Kolpik—a traditional Slavic headdress, worn by unmarried sons and grandsons of many rebbes on the Sabbath. The kolpik is also worn by some rebbes themselves on special occasions.

- Black felt fedoras—worn by Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidim dating back to the style of the 1940s and 50s. They are the same as the hats worn by many non-Hasidic Haredim.

- Shtofener—Various forms of felt open crown hats. Affiliation can sometimes be identified by whether there is a pinch in the middle of the top or not, as well as the type of brim. Many Satmar laymen wear a type of open crown hat that resembles a bowler hat with rounded edges on the brim.

- Samet (velvet) or biber (beaver)—Hats worn by Galician and Hungarian Hasidim. There are many types of samet hats, most notably the "high" and "flat" varieties. The "flat" type is worn by Satmar Hasidim and some others. They are called beaver hats even though today they are usually made from rabbit.

- Kutchma—A small fur hat worn by many Hasidic laymen during weekdays in the winter. Today this hat is sometimes made from cheaper materials, such as polyester. This hat is referred to as a shlyapka (шляпка), by Russian Jews.

Other distinct clothing

Many, though not all, Hasidim traditionally do not wear wristwatches but instead use a watch and chain and a vest (also right-over-left). There are also various traditions regarding socks, breeches, shoes or boots, and suit styles.

Hair

Following a biblical commandment not to shave the sides of one's face, male members of most Hasidic groups wear long, uncut sideburns called payoth (Ashkenazi Hebrew peyos, Yiddish peyes). Many Hasidim shave off the rest of their hair on the top of their head.

Not every hasidic group requires long peyos, and not all Jewish men with peyos are Hasidic, but all Hasidic groups discourage the shaving of one's beard, although some hasidic laymen ignore this dictum. Hasidic boys generally receive their first haircuts ceremonially at the age of three years.

Tzitzit

The white threads seen at the waists of Hasidim and other Orthodox Jewish males are called tzitzit. The requirement to wear fringes comes from the Book of Numbers: "Speak to the children of Israel, and bid them that they make them fringes on the borders of their garments throughout their generations" (Numbers 15:38). In order to fulfill this commandment, Orthodox males wear a talles katan, a square white garment with the fringes at the corners. By tradition, a hasidic boy will receive his first fringed garment on his third birthday, the same day as his first haircut. Most Orthodox Jews wear the talles katan under their shirts, where it is unnoticeable except for the strings that many leave hanging out. Many Hasidim, as well as some other Haredim, wear the talles katan over their shirt instead.

Women and families

As with other traditions of Orthodox Judaism, hasidic women may not be ordained to teach men, lead religious services, or otherwise assume positions of community leadership except among other women. In common with all Haredim, Hasidic men will not touch or even shake hands with anyone of the opposite sex other than their wife, mother, or female offspring. The converse applies for women.

Hasidic women wear clothing of less distinctive appearance than that of their male counterparts, but which answers to the principles of tzeniut—modest dress—in the sense of Jewish law. As with all Haredi women, the standard is long, conservative skirts, and sleeves past the elbow. Otherwise, female Hasidic fashion remains on the conservative side of secular women's fashion. Most Hasidic women do not wear red clothing.

In keeping with Jewish law married Hasidic women cover their hair. In many Hasidic groups the women wear wigs for this purpose. In some of these groups the women might also wear a tichel (scarf) or hat on top of the wig either on a regular basis or when attending services or other religious events. Other groups consider wigs too natural looking, so they simply put their hair into kerchiefs. In some groups, such as Satmar, married women are expected to shave their heads and wear head kerchiefs. Hasidim allow uncovered hair for women before marriage.

Hasidic men and women, as customary in Haredi Judaism, usually meet through matchmakers in a process called a shidduch, but marriages involve the mutual consent of both the couple and of the parents. Bride and groom are expected to be about the same age. Marriage age ranges from 17-25, with 18-21 considered the norm.

Hasidic thought emphasized the holiness of sex, and the Jewish religion stresses the importance of married couples enjoying the pleasure of sexual intercourse as a divine command. Many pious Hasidic couples thus follow strict regulations regarding what types of sexual relations are allowed and what positions etc. They also follow the general halakhic customs regarding ritual purification and refrain from sexual relations during a woman's menstrual cycle.

Hasidic Jews, like many other Orthodox Jews, produce large families. Many sects follow this custom out of what they consider a biblical mandate to 'be fruitful and multiply. The average chasidic family in the United States has 7.9 children.[1]

Languages

Most Hasidim speak the language of their countries of residence, but use Yiddish among themselves as a way of remaining distinct and preserving tradition. Thus hasidic children are still learning Yiddish today, one of the major factors in keeping the language alive since modern Hebrew was adopted in Israel. Yiddish newspapers are still published in hasidic communities, and Yiddish fiction is also being written, primarily aimed at hasidic women. Films in Yiddish are also produced within the Hasidic community and released immediately as DVDs.

Some Hasidic groups actively oppose the everyday use of Hebrew, which is considered a holy tongue appropriate more for liturgical use, prayer, and scripture reading. Hence Yiddish is the vernacular and common tongue for Hasidim around the world.

Notes

- ↑ Jack Wertheimer, Jews and the Jewish Birthrate Aish. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Altshuler, Mor. The Messianic Secret of Hasidism. Brill's series in Jewish studies, v. 39. Leiden: Brill, 2006. ISBN 9789004153561.

- Buber, Martin. Tales of the Hasidim. New York: Schocken Books, 1991. ISBN 9780805209952.

- Elior, Rachel. The Mystical Origins of Hasidism. Oxford: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2006. ISBN 9781904113041.

- Heschel, Abraham Joshua, and Samuel H. Dresner. The Circle of the Baal Shem Tov: Studies in Hasidism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985. ISBN 9780226329604.

- Lamm, Norman. The Religious Thought of Hasidism: Text and Commentary. Sources and studies in Kabbalah, Hasidism, and Jewish thought, v. 4. New York: Michael Scharf Publication Trust of Yeshiva University Press, 1999. ISBN 9780881254402.

- Rabinowicz, Tzvi. The Encyclopedia of Hasidism. Northvale, N.J.: Jason Aronson, 1996. ISBN 9781568211237.

External links

All links retrieved December 24, 2021.

- Hasidim, Hasidism Jewish Encyclopedia

- Orthodox Judaism: Hasidism Jewish Virtual Library

- Chassidic Texts

- Archives of Chassidic Stories

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.