Difference between revisions of "Guerrilla warfare" - New World Encyclopedia

m |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

{{Started}}{{Claimed}}{{Contracted}} | {{Started}}{{Claimed}}{{Contracted}} | ||

| − | '''Guerrilla warfare''' (also spelled '''guerilla''') is a method of combat by which a smaller group of combatants attempts to use its mobility to defeat a larger, and consequently less mobile, army. It is typical that a smaller guerrilla army will either use its defensive status to draw its opponent into terrain which is better suited to the former or take advantage of its greater mobility by conducting strategic surprise attacks. This method of conducting war can be traced back at least as far as the 3rd century B.C.E. to describe [[Fabius Maximus]]’ strategies against [[Hannibal]]’s forces during the [[Second Punic War]], but it is most frequently associated with armed struggles, usually of a revolutionary nature, from the 19th century on. | + | '''Guerrilla warfare''' (also spelled '''guerilla''') is a method of combat by which a smaller group of combatants attempts to use its mobility to defeat a larger, and consequently less mobile, army. It is typical that a smaller guerrilla army will either use its defensive status to draw its opponent into terrain which is better suited to the former or take advantage of its greater mobility by conducting strategic surprise attacks. This method of conducting war can be traced back at least as far as the 3rd century B.C.E..E. to describe [[Fabius Maximus]]’ strategies against [[Hannibal]]’s forces during the [[Second Punic War]], but it is most frequently associated with armed struggles, usually of a revolutionary nature, from the 19th century on. |

Guerrilla warfare should not be confused with covering or screening operations by a regular force, or defensive maneuver to avoid battle, such as that conducted by ancient [[Roman]] general [[Fabius Maximus]] (with conventional forces) against [[Hannibal]]. Nor should it be confused with simple small unit tactics such as ambushes, or light probing attacks which most conventional armies incorporate as part of their routine training. A regular army may use guerrilla tactics for long-range [[reconnaissance]], as in [[LRRP]] or [[Sissi (Finnish guerrilla)|sissi]] tactics, but guerrillas are almost always part of a [[resistance movement]]. | Guerrilla warfare should not be confused with covering or screening operations by a regular force, or defensive maneuver to avoid battle, such as that conducted by ancient [[Roman]] general [[Fabius Maximus]] (with conventional forces) against [[Hannibal]]. Nor should it be confused with simple small unit tactics such as ambushes, or light probing attacks which most conventional armies incorporate as part of their routine training. A regular army may use guerrilla tactics for long-range [[reconnaissance]], as in [[LRRP]] or [[Sissi (Finnish guerrilla)|sissi]] tactics, but guerrillas are almost always part of a [[resistance movement]]. | ||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| − | Guerrilla, from the [[Spanish language|Spanish]] term ''guerra'', or ''War'', with the ''-illa'' ending diminutive, could be translated as ''small war''. The use of the diminutive is probably to evoke the difference in size between the guerrilla army and the state army against which they fight. | + | Guerrilla, from the [[Spanish language|Spanish]] term ''guerra'', or ''War'', with the ''-illa'' ending diminutive, could be translated as ''small war''. The use of the diminutive is probably to evoke the difference in size between the guerrilla army and the state army against which they fight. The term was invented in [[Spain]] to describe the tactics used to resist the [[France|French]] [[regime]] instituted by [[Napoleon I of France|Napoleon Bonaparte]]. Its meaning was soon broadened to refer to any similar resistance of any time or place. The Spanish word for guerrilla fighter is ''guerrillero''. The change of usage of ''guerrilla'' from the tactics employed to the person implementing them is a late 19th century mistake: in most languages the word still denotes the specific style of warfare. This, however, is changing under the influence of broad English usage. |

==Continuum of guerrilla warfare== | ==Continuum of guerrilla warfare== | ||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

Modern guerrilla warfare at its fullest (high end) elaboration should be conceived of as an integrated process, complete with sophisticated [[doctrine]], organization, specialist skills and [[propaganda]] capabilities. Guerrillas can operate as small, scattered bands of raiders, but they can also work side by side with regular forces, or combine for far ranging mobile operations in [[squad]], [[platoon]] or [[battalion]] sizes, or even form conventional units. Based on their level of sophiscation and organization, they can shift between all these modes as the situation demands. Guerrilla warfare is flexible, not static. | Modern guerrilla warfare at its fullest (high end) elaboration should be conceived of as an integrated process, complete with sophisticated [[doctrine]], organization, specialist skills and [[propaganda]] capabilities. Guerrillas can operate as small, scattered bands of raiders, but they can also work side by side with regular forces, or combine for far ranging mobile operations in [[squad]], [[platoon]] or [[battalion]] sizes, or even form conventional units. Based on their level of sophiscation and organization, they can shift between all these modes as the situation demands. Guerrilla warfare is flexible, not static. | ||

| − | Commando operations are not guerrilla warfare (Richard Taber, "The War of the Flea : Guerrilla Warfare, Theory and Practice" | + | Commando operations are not guerrilla warfare (Richard Taber, "The War of the Flea : Guerrilla Warfare, Theory and Practice." [[Paladin Press|Paladin]], London, 1977) while they lack the political goal. Commando troops, as the British commando, were a branch of the armed forces. Guerrilla warfare is the expression of [[Sun Tzu|Sun Tzu's]] [[The Art of War|Art of War]], in contrast to [[Carl von Clausewitz|Clausewitz's]] [[Total war|unlimited use of brute force]]. Guerrilla warfare is also distinguished from the small unit tactics used in screening or recon operations typical of conventional forces. It is also different from the activities of bandits, pirates or robbers. Such forces may use ''guerrilla-like'' tactics, but their primary purpose is booty, and not a clear political objective. |

==Tactics and strategy== | ==Tactics and strategy== | ||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

[[Image:simpleguorg.jpg|right]] | [[Image:simpleguorg.jpg|right]] | ||

| − | Guerrilla organization can range from small local rebel groups with a few dozen participants, to tens of thousands of fighters, deploying from tiny cells to formations of regimental strength. In most cases, there will be leadership aiming for a clear political objective. The organization will typically be structured into political and military wings, sometimes allowing the political leadership to claim "plausible denial" for military attacks.<ref> "Insurgency & Terrorism: Inside Modern Revolutionary Warfare" | + | Guerrilla organization can range from small local rebel groups with a few dozen participants, to tens of thousands of fighters, deploying from tiny cells to formations of regimental strength. In most cases, there will be leadership aiming for a clear political objective. The organization will typically be structured into political and military wings, sometimes allowing the political leadership to claim "plausible denial" for military attacks.<ref> "Insurgency & Terrorism: Inside Modern Revolutionary Warfare," Bard E. O'Neill </ref>The most fully elaborated guerrilla warfare structure is seen by the Chinese and Vietnamese communists during the revolutionary wars of East and Southeast Asia.<ref name=lanning>Lanning, Michael Lee and Dan Cragg. 1993. ''Inside the VC and the NVA'' Ballantine Books. ISBN 0804105006</ref> |

===Types of operations=== | ===Types of operations=== | ||

| − | Guerrilla operations typically include a variety of attacks on transportation routes, individual groups of police or military, installations and structures, economic enterprises, and targeted civilians. | + | Guerrilla operations typically include a variety of attacks on transportation routes, individual groups of police or military, installations and structures, economic enterprises, and targeted civilians. Attacking in small groups, using camouflage and often captured weapons of that enemy, the guerilla force can constantly keep pressure on its foes and diminish its numbers, while still allowing escape with relatively few casualties. The intention of such attacks is not only military but political, aiming to demoralize target populations or governments, or goading an overreaction that forces the population to take sides for or against the guerrillas. Examples range from the chopping off of limbs in various internal African rebellions, to the suicide bombings of Palestine and Sri Lanka, to sophisticated maneuvers by Viet Cong and NVA forces against military bases and formations. |

===Surprise and intelligence=== | ===Surprise and intelligence=== | ||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

Popular mass support in a confined local area or country however is not always strictly necessary. Guerrillas and revolutionary groups can still operate using the protection of a friendly regime, drawing supplies, weapons, intellligence, local security and diplomatic cover. The Al Queda organization is an example of the latter type, drawing sympathizers and support primarily from the wide-ranging Muslim world, even after American attacks eliminated the umbrella of a friendly Taliban regime in Afghanistan. | Popular mass support in a confined local area or country however is not always strictly necessary. Guerrillas and revolutionary groups can still operate using the protection of a friendly regime, drawing supplies, weapons, intellligence, local security and diplomatic cover. The Al Queda organization is an example of the latter type, drawing sympathizers and support primarily from the wide-ranging Muslim world, even after American attacks eliminated the umbrella of a friendly Taliban regime in Afghanistan. | ||

| − | An apathetic or hostile population makes life difficult for guerrillas and strenuous attempts are usually made to gain their support. These may involve not only persuasion, but a calculated policy of intimidation. Guerrilla forces may characterize a variety of operations as a liberation struggle, but this may or may not result in sufficient support from affected civilians. Other factors, including ethnic and religious hatreds, can make a simple national liberation claim untenable. Whatever the exact mix of persuasion or coercion used by guerrillas, relationships with civil populations are one of the most important factors in their success or failure. <ref>"Defeating Communist Insurgency: The Lessons of Malaya and Vietnam" | + | An apathetic or hostile population makes life difficult for guerrillas and strenuous attempts are usually made to gain their support. These may involve not only persuasion, but a calculated policy of intimidation. Guerrilla forces may characterize a variety of operations as a liberation struggle, but this may or may not result in sufficient support from affected civilians. Other factors, including ethnic and religious hatreds, can make a simple national liberation claim untenable. Whatever the exact mix of persuasion or coercion used by guerrillas, relationships with civil populations are one of the most important factors in their success or failure. <ref>"Defeating Communist Insurgency: The Lessons of Malaya and Vietnam," Robert Thompson </ref> |

===Use of terror=== | ===Use of terror=== | ||

| − | In some cases, the use of [[terror]] can be an aspect of guerrilla warfare. Terror is used to focus international attention on the guerrilla cause, liquidate opposition leaders, extort cash from targets, intimidate the general population, create economic losses, and keep followers and potential defectors in line. Such tactics may backfire and cause the civil population to withdraw its support, or to back countervailing forces against the guerrillas. <ref>"Insurgency & Terrorism: Inside Modern Revolutionary Warfare" | + | In some cases, the use of [[terror]] can be an aspect of guerrilla warfare. Terror is used to focus international attention on the guerrilla cause, liquidate opposition leaders, extort cash from targets, intimidate the general population, create economic losses, and keep followers and potential defectors in line. Such tactics may backfire and cause the civil population to withdraw its support, or to back countervailing forces against the guerrillas. <ref>"Insurgency & Terrorism: Inside Modern Revolutionary Warfare," Bard E. O'Neill</ref> |

Such situations occurred in Israel, where suicide bombings encouraged most Israeli opinion to take a harsh stand against Palestinian attackers, including general approval of "targeted killings" to liquidate enemy cells and leaders.<ref>Steven R. David (September 2002). "Fatal Choices: Israel's Policy of Targeted Killing" (PDF). THE BEGIN-SADAT CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES; BAR-ILAN UNIVERSITY. Retrieved on 2006-08-01. </ref> In the Philippines and Malaysia, communist terror strikes helped turn civilian opinion against the insurgents. In Peru and some other South American countries, civilian opinion at times backed the harsh countermeasures used by authoritarian regimes against revolutionary movements. (See the Peruvian regime of [[Alberto Fujimori]] for example). | Such situations occurred in Israel, where suicide bombings encouraged most Israeli opinion to take a harsh stand against Palestinian attackers, including general approval of "targeted killings" to liquidate enemy cells and leaders.<ref>Steven R. David (September 2002). "Fatal Choices: Israel's Policy of Targeted Killing" (PDF). THE BEGIN-SADAT CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES; BAR-ILAN UNIVERSITY. Retrieved on 2006-08-01. </ref> In the Philippines and Malaysia, communist terror strikes helped turn civilian opinion against the insurgents. In Peru and some other South American countries, civilian opinion at times backed the harsh countermeasures used by authoritarian regimes against revolutionary movements. (See the Peruvian regime of [[Alberto Fujimori]] for example). | ||

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

===Guidelines=== | ===Guidelines=== | ||

| − | The widely distributed and influential work of Sir. Robert Thompson, counter-insurgency expert in Malaysia, offers several such guidelines. Thompson's underlying assumption is that of a country minimally committed to the rule of law and better governance. Numerous other regimes, however, give such considerations short shrift, and their counterguerrilla operations have involved mass murder, genocide, starvation and the massive spread of terror, torture and execution. The totalitarian regimes of Stalin and Hitler are classic examples, as are more modern conflicts in places like Afghanistan. In Afghanistan's anti-Mujahideen war for example, the Soviets implemented a ruthless policy of wastage and depopulation, driving over one third of the Afghan population into exile (over 5 million people), and carrying out widespread destruction of villages, granaries, crops, herds and irrigation systems, including the deadly and widespread mining of fields and pastures. The basic elements of Thompson's<ref>"Defeating Communist Insurgency: The Lessons of Malaya and Vietnam" | + | The widely distributed and influential work of Sir. Robert Thompson, counter-insurgency expert in Malaysia, offers several such guidelines. Thompson's underlying assumption is that of a country minimally committed to the rule of law and better governance. Numerous other regimes, however, give such considerations short shrift, and their counterguerrilla operations have involved mass murder, genocide, starvation and the massive spread of terror, torture and execution. The totalitarian regimes of Stalin and Hitler are classic examples, as are more modern conflicts in places like Afghanistan. In Afghanistan's anti-Mujahideen war for example, the Soviets implemented a ruthless policy of wastage and depopulation, driving over one third of the Afghan population into exile (over 5 million people), and carrying out widespread destruction of villages, granaries, crops, herds and irrigation systems, including the deadly and widespread mining of fields and pastures. The basic elements of Thompson's<ref>"Defeating Communist Insurgency: The Lessons of Malaya and Vietnam," Robert Thompson </ref> moderate approach are: |

#A viable competing vision that comprehensively mobilizes popular support. | #A viable competing vision that comprehensively mobilizes popular support. | ||

#Reasonable concessions where necessary. | #Reasonable concessions where necessary. | ||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

In [[Iraq]], most of the deaths since the 2003 US conquest have not been suffered by US troops but by civilians, as warring factions plunged the country into civil war based on ethnic and religious hostilities. Arguments vary on whether such turmoil will succeed in turning American opinion against the US troop deployment. However the use of attacks against civilians to create an atmosphere of chaos (and thus political advantage where the atmosphere causes foreign occupiers to withdraw or offer concessions), is well established in guerrilla and national liberation struggles. Claims and counterclaims of the morality of such attacks, or whether guerrillas should be classified as "terrorists" or "freedom fighters" are beyond the scope of this article. See [[Terrorism]] and [[Genocide]] for a more in-depth discussion of the moral and ethical implications of targeting civilians. | In [[Iraq]], most of the deaths since the 2003 US conquest have not been suffered by US troops but by civilians, as warring factions plunged the country into civil war based on ethnic and religious hostilities. Arguments vary on whether such turmoil will succeed in turning American opinion against the US troop deployment. However the use of attacks against civilians to create an atmosphere of chaos (and thus political advantage where the atmosphere causes foreign occupiers to withdraw or offer concessions), is well established in guerrilla and national liberation struggles. Claims and counterclaims of the morality of such attacks, or whether guerrillas should be classified as "terrorists" or "freedom fighters" are beyond the scope of this article. See [[Terrorism]] and [[Genocide]] for a more in-depth discussion of the moral and ethical implications of targeting civilians. | ||

| − | Guerrillas are in danger of not being recognized as lawful [[combatant]]s because they may not wear a [[uniform]], (to mingle with the local population), or their uniform and distinctive emblems may not be recognized as such by their opponents. Article 44, sections 3 and 4 of the 1977 [[Protocol I|First Additional Protocol]] to the [[Geneva Conventions]], "relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts" | + | Guerrillas are in danger of not being recognized as lawful [[combatant]]s because they may not wear a [[uniform]], (to mingle with the local population), or their uniform and distinctive emblems may not be recognized as such by their opponents. Article 44, sections 3 and 4 of the 1977 [[Protocol I|First Additional Protocol]] to the [[Geneva Conventions]], "relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts," does recognize combatants who, because of the nature of the conflict, do not wear uniforms as long as they carry their weapons openly during military operations. This gives non-uniformed guerrillas lawful combatant status against countries that have ratified this convention. However, the same protocol states in Article 37.1.c that "''the feigning of civilian, non-combatant status''" shall constitute [[perfidy]] and is prohibited by the Geneva Conventions. |

==Examples== | ==Examples== | ||

| Line 122: | Line 122: | ||

Mongols also faced guerrillas composed by armed peasants in [[Hungary]] after the [[Battle of Mohi]]. During [[The Deluge (Polish history)|The Deluge]] in [[Poland]] guerrilla tactics were applied. In the 19th century, peoples of the [[Balkans]] used guerrilla tactics to fight the [[Ottoman empire]]. In the [[100 years war]] between England and France, commander [[Bertrand du Guesclin]] used guerrilla tactics to pester the English invaders. During the [[Scanian War]], a pro-Danish guerrilla group known as the [[Snapphane]] fought against the Swedes. In 17th century [[Ireland]], Irish irregulars called [[tories]] and [[rapparees]] used guerrilla warfare in the [[Irish Confederate Wars]] and the [[Williamite war in Ireland]]. The [[Finland|Finns]] guerrillas, [[Sissi (Finnish guerrilla)|''sissis'']], fought against [[Russia]]n occupation troops in the [[Great Northern War]] 1710-1721. The Russians retaliated brutally on civilian populace; the period is called ''Isoviha'' (Grand Hatred) in Finland. | Mongols also faced guerrillas composed by armed peasants in [[Hungary]] after the [[Battle of Mohi]]. During [[The Deluge (Polish history)|The Deluge]] in [[Poland]] guerrilla tactics were applied. In the 19th century, peoples of the [[Balkans]] used guerrilla tactics to fight the [[Ottoman empire]]. In the [[100 years war]] between England and France, commander [[Bertrand du Guesclin]] used guerrilla tactics to pester the English invaders. During the [[Scanian War]], a pro-Danish guerrilla group known as the [[Snapphane]] fought against the Swedes. In 17th century [[Ireland]], Irish irregulars called [[tories]] and [[rapparees]] used guerrilla warfare in the [[Irish Confederate Wars]] and the [[Williamite war in Ireland]]. The [[Finland|Finns]] guerrillas, [[Sissi (Finnish guerrilla)|''sissis'']], fought against [[Russia]]n occupation troops in the [[Great Northern War]] 1710-1721. The Russians retaliated brutally on civilian populace; the period is called ''Isoviha'' (Grand Hatred) in Finland. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the [[Napoleonic Wars]] many of the armies lived off the land. This often led to some resistance by the local population if the army did not pay fair prices for produce they consumed. Usually this resistance was sporadic, and not very successful, so it is not classified as guerrilla action. In the [[Peninsular War]], however, the British, encouraged by the spontaneous mass resistance in Spain against Napoleon, gave aid to the Spanish guerrillas who tied down tens of thousands of French troops. The continual losses of troops caused Napoleon to describe this conflict his "Spanish ulcer." The British gave this aid because it cost them much less than it would have done to equip British soldiers to face the French troops in conventional warfare. This was one of the most successful partisan wars in history and was where the word ''guerrilla'' was first used in this context. The [[Oxford English Dictionary]] lists [[Arthur Wellesley|Wellington]] as the oldest known source, speaking of "Guerrillas" in 1809. | ||

=== American Revolutionary War === | === American Revolutionary War === | ||

| Line 138: | Line 140: | ||

=== Latin America === | === Latin America === | ||

| − | In the [[Mexican Revolution]] from 1910 to 1920, the populist revolutionary leader [[Emiliano Zapata]] employed the use of predominately guerrilla tactics. His forces, composed entirely of peasant farmers turned soldiers, wore no uniform and would easily blend into the general population after an operation's completion. They would have young soldiers, called "dynamite boys" | + | In the [[Mexican Revolution]] from 1910 to 1920, the populist revolutionary leader [[Emiliano Zapata]] employed the use of predominately guerrilla tactics. His forces, composed entirely of peasant farmers turned soldiers, wore no uniform and would easily blend into the general population after an operation's completion. They would have young soldiers, called "dynamite boys," hurl cans filled with explosives into enemy barracks, and then a large number of lightly armed soldiers would emerge from the surrounding area to attack it. Although Zapata's forces met considerable success, his strategy backfired as government troops, unable to distinguish his soldiers from the normal population, waged a broad and brutal campaign against the latter. |

In the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, [[Latin America]] had a number of [[urban guerrilla]] movements whose strategy was to destabilize regimes and provoke a counter-reaction by the military. The theory was that a harsh military regime would oppress the [[middle class]]es who would then support the guerrillas and create a popular uprising. | In the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, [[Latin America]] had a number of [[urban guerrilla]] movements whose strategy was to destabilize regimes and provoke a counter-reaction by the military. The theory was that a harsh military regime would oppress the [[middle class]]es who would then support the guerrillas and create a popular uprising. | ||

| Line 153: | Line 155: | ||

=== World War II === | === World War II === | ||

[[Image:Soviet guerilla.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Soviet partisan fighters behind German lines in Belarus in 1943]] | [[Image:Soviet guerilla.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Soviet partisan fighters behind German lines in Belarus in 1943]] | ||

| − | In [[World War II]], several guerrilla organisations (often known as [[resistance movement]]s) operated in the countries occupied by [[Nazi Germany]]. These included the Polish [[Home Army]], [[Slovak National Uprising]], [[Soviet partisans]] (see also [[Russian Guerrilla Warfare of WWII]]), [[National Liberation Army of Yugoslavia|Yugoslav Partisans]], Bulgarian NOVA, [[French resistance]] or [[Maquis (WW2)|Maquis]], Italian partisans, [[ELAS]] and royalist forces in [[Greece]]. Many of these organisations received help from the [[Special Operations Executive]] (SOE) which along with the [[British Commando|commandos]] was initiated by [[Winston Churchill]] to "set Europe ablaze." The SOE was originally designated as 'Section D' of [[MI6]] but its aid to resistance movements to start fires clashed with MI6's primary role as an intelligence-gathering agency. When Britain was under threat of invasion, SOE trained [[Auxiliary Units]] to conduct guerrilla warfare in the event of invasion. Not only did SOE help the resistance to tie down many German units as garrison troops, so directly aiding the conventional war effort, but also guerrilla incidents in occupied countries were useful in the propaganda war, helping to repudiate German claims that the occupied countries were pacified and broadly on the side of the Germans. | + | In [[World War II]], several guerrilla organisations (often known as [[resistance movement]]s) operated in the countries occupied by [[Nazi Germany]]. These included the Polish [[Home Army]], [[Slovak National Uprising]], [[Soviet partisans]] (see also [[Russian Guerrilla Warfare of WWII]]), [[National Liberation Army of Yugoslavia|Yugoslav Partisans]], Bulgarian NOVA, [[French resistance]] or [[Maquis (WW2)|Maquis]], Italian partisans, [[ELAS]] and royalist forces in [[Greece]]. Many of these organisations received help from the [[Special Operations Executive]] (SOE) which along with the [[British Commando|commandos]] was initiated by [[Winston Churchill]] to "set Europe ablaze." The SOE was originally designated as 'Section D' of [[MI6]] but its aid to resistance movements to start fires clashed with MI6's primary role as an intelligence-gathering agency. When Britain was under threat of invasion, SOE trained [[Auxiliary Units]] to conduct guerrilla warfare in the event of invasion. Not only did SOE help the resistance to tie down many German units as garrison troops, so directly aiding the conventional war effort, but also guerrilla incidents in occupied countries were useful in the propaganda war, helping to repudiate German claims that the occupied countries were pacified and broadly on the side of the Germans. Despite these minor successes, many historians believe that the efficacy of the European resistance movements has been greatly exaggerated in popular novels, films and other media. Contrary to popular belief, the resistance groups were only able to seriously counter the German in areas that offered the protection of rugged terrain. In relatively flat, open areas, such as France, the resistance groups were all too vulnerable to decimation by German regulars and pro-German collaborationists. Only when operating in concert with conventional Allied units were the resistance groups to prove indispensable. |

=== Post World War II Europe === | === Post World War II Europe === | ||

| Line 167: | Line 169: | ||

Over time, more of the fighting was conducted by the North Vietnamese Army and the character of the war become increasingly conventional. The final offensive into [[South Vietnam]] in 1975 was a mostly conventional military operation in which guerrilla warfare played a minor, supporting role. | Over time, more of the fighting was conducted by the North Vietnamese Army and the character of the war become increasingly conventional. The final offensive into [[South Vietnam]] in 1975 was a mostly conventional military operation in which guerrilla warfare played a minor, supporting role. | ||

| − | The [[Cu Chi Tunnels]] (''Địa đạo Củ Chi'') was a major base for guerrilla warfare during the Vietnam War. | + | The [[Cu Chi Tunnels]] (''Địa đạo Củ Chi'') was a major base for guerrilla warfare during the Vietnam War. Located about 60km northwest of Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City), the Viet Cong used the complex system tunnels to hide and live during the days and come up to fight at nights. |

=== Israel and the Palestinian Territories=== | === Israel and the Palestinian Territories=== | ||

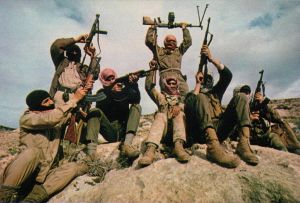

[[Image:PFLP-group-1969.jpg|thumb|left| In the mountains east of the Jordan River, a patrol from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine punctuates a battle hymn with Soviet and (top left) Egyptian weapons. Early 1969.]] | [[Image:PFLP-group-1969.jpg|thumb|left| In the mountains east of the Jordan River, a patrol from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine punctuates a battle hymn with Soviet and (top left) Egyptian weapons. Early 1969.]] | ||

| − | European Jews fleeing from [[anti-Semitic]] violence (especially Russian [[pogroms]]) immigrated in increasing numbers to [[Palestine]]. | + | European Jews fleeing from [[anti-Semitic]] violence (especially Russian [[pogroms]]) immigrated in increasing numbers to [[Palestine]]. When the British restricted Jewish immigration to the region (see [[White Paper of 1939]]), Jewish Palestinians began to use guerrilla warfare for two purposes: to bring in more Jewish refugees, and to turn the tide of British sentiment at home. Jewish groups such as the [[Lehi]] and the [[Irgun]] - many of whom had experience in the [[Warsaw Ghetto Uprising|Warsaw Ghetto battles]] against the Nazis, fought British soldiers whenever they could, including the [[King David Hotel Bombing|bombing of the King David Hotel]]. |

| − | The creation of the state of Israel might be considered one of the greatest achievements of guerrilla warfare. | + | The creation of the state of Israel might be considered one of the greatest achievements of guerrilla warfare. The Jewish forces were composed of spontaneous groups of civilians working without formal military structure, fighting the British Empire, which had just emerged victorious from [[World War II]]. Some of these groups were amalgamated into the [[Israel Defence Force]] and subsequently fought in the [[1948 War of Independence]].) |

[[Palestinian]] groups, among them the [[Palestinian Liberation Army]], soon initiated their own guerrilla warfare against the new Jewish state. | [[Palestinian]] groups, among them the [[Palestinian Liberation Army]], soon initiated their own guerrilla warfare against the new Jewish state. | ||

| Line 188: | Line 190: | ||

The ongoing use of guerrilla tactics is due to their efficacy and economy. The fact that small, cheap forces can be used makes them appealing to military commanders operating wars on a budget. In today's single-superpower world, wars have become smaller and less conventional, which allows for the continued place of guerrilla tactics. | The ongoing use of guerrilla tactics is due to their efficacy and economy. The fact that small, cheap forces can be used makes them appealing to military commanders operating wars on a budget. In today's single-superpower world, wars have become smaller and less conventional, which allows for the continued place of guerrilla tactics. | ||

| − | Many guerrillas have taken to using [[terrorism|terrorist]] tactics. Terrorism and guerrilla warfare are not synonymous, however. Terrorism, on one hand, is a term used to describe violence or other harmful acts committed (or threatened) against civilians by groups or persons for political or other ideological goals.<ref>"The divergent assessments of the same evidence on such an important issue shocks a leading terrorism researcher. 'The notion of terrorism is fairly straightforward — it is ideologically or politically motivated violence directed against civilian targets.'" said Professor Martin Rudner, director of the Canadian Centre of Intelligence and Security Studies at Ottawa's Carleton University." Humphreys, Adrian. [http://www.canada.com/nationalpost/news/story.html?id=a64f73d2-f672-4bd0-abb3-2584029db496 "One official's 'refugee' is another's 'terrorist'"], ''[[National Post]],'' January 17, 2006.</ref> Most definitions of terrorism include only those acts which are: intended to create fear or "terror," are perpetrated for a political goal (as opposed to a [[hate crime]] or "madman" attack), and deliberately target "non-combatants" | + | Many guerrillas have taken to using [[terrorism|terrorist]] tactics. Terrorism and guerrilla warfare are not synonymous, however. Terrorism, on one hand, is a term used to describe violence or other harmful acts committed (or threatened) against civilians by groups or persons for political or other ideological goals.<ref>"The divergent assessments of the same evidence on such an important issue shocks a leading terrorism researcher. 'The notion of terrorism is fairly straightforward — it is ideologically or politically motivated violence directed against civilian targets.'" said Professor Martin Rudner, director of the Canadian Centre of Intelligence and Security Studies at Ottawa's Carleton University." Humphreys, Adrian. [http://www.canada.com/nationalpost/news/story.html?id=a64f73d2-f672-4bd0-abb3-2584029db496 "One official's 'refugee' is another's 'terrorist'"], ''[[National Post]],'' January 17, 2006.</ref> Most definitions of terrorism include only those acts which are: intended to create fear or "terror," are perpetrated for a political goal (as opposed to a [[hate crime]] or "madman" attack), and deliberately target "non-combatants." Some definitions exclude acts committed by "legitimate" [[government|governments]], however this exclusion is not universally accepted. In many cases the notion of "legitimate" and the definition of "combatant" is disputed, especially by partisans to the conflict in question. Guerrillas, on the other hand, have traditionally targeted clearly defined military targets using the tactics outlined above. Terrorist tactics have been added to the arsenals of many guerrilla groups. This addition reflects the danger inherent to confronting superior forces through guerrilla action and the fact that civilians are often easier to target. |

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

<small><references /></small> | <small><references /></small> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| + | * Lanning, Michael Lee and Dan Cragg. 1993. ''Inside the VC and the NVA'' Ballantine Books. ISBN 0804105006 | ||

* Mackey, Robert R. 2004. ''The UnCivil War: Irregular Warfare in the Upper South, 1861–1865''. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press ISBN 0806136243 | * Mackey, Robert R. 2004. ''The UnCivil War: Irregular Warfare in the Upper South, 1861–1865''. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press ISBN 0806136243 | ||

* Mao, Zedong (formerly Tse-tung). [1937] 2000. ''On Guerrilla Warfare.'' University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252068920 | * Mao, Zedong (formerly Tse-tung). [1937] 2000. ''On Guerrilla Warfare.'' University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252068920 | ||

* Marighella, Carlos. 1969. [http://www.marxists.org/archive/marighella-carlos/1969/06/minimanual-urban-guerrilla/index.htm ''Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla.''] Retrieved March 21, 2007. | * Marighella, Carlos. 1969. [http://www.marxists.org/archive/marighella-carlos/1969/06/minimanual-urban-guerrilla/index.htm ''Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla.''] Retrieved March 21, 2007. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credits|Guerrilla_warfare|113209263|}} | {{Credits|Guerrilla_warfare|113209263|}} | ||

Revision as of 22:06, 21 March 2007

Guerrilla warfare (also spelled guerilla) is a method of combat by which a smaller group of combatants attempts to use its mobility to defeat a larger, and consequently less mobile, army. It is typical that a smaller guerrilla army will either use its defensive status to draw its opponent into terrain which is better suited to the former or take advantage of its greater mobility by conducting strategic surprise attacks. This method of conducting war can be traced back at least as far as the 3rd century B.C.E. to describe Fabius Maximus’ strategies against Hannibal’s forces during the Second Punic War, but it is most frequently associated with armed struggles, usually of a revolutionary nature, from the 19th century on.

Guerrilla warfare should not be confused with covering or screening operations by a regular force, or defensive maneuver to avoid battle, such as that conducted by ancient Roman general Fabius Maximus (with conventional forces) against Hannibal. Nor should it be confused with simple small unit tactics such as ambushes, or light probing attacks which most conventional armies incorporate as part of their routine training. A regular army may use guerrilla tactics for long-range reconnaissance, as in LRRP or sissi tactics, but guerrillas are almost always part of a resistance movement.

Primary contributors to modern theories of guerrilla war include Mao Zedong, Abd el-Krim, T. E. Lawrence, John Brown, Vo Nguyen Giap, Josip Broz Tito, Michael Collins, Tom Barry, Che Guevara, and Charles de Gaulle.

Etymology

Guerrilla, from the Spanish term guerra, or War, with the -illa ending diminutive, could be translated as small war. The use of the diminutive is probably to evoke the difference in size between the guerrilla army and the state army against which they fight. The term was invented in Spain to describe the tactics used to resist the French regime instituted by Napoleon Bonaparte. Its meaning was soon broadened to refer to any similar resistance of any time or place. The Spanish word for guerrilla fighter is guerrillero. The change of usage of guerrilla from the tactics employed to the person implementing them is a late 19th century mistake: in most languages the word still denotes the specific style of warfare. This, however, is changing under the influence of broad English usage.

Continuum of guerrilla warfare

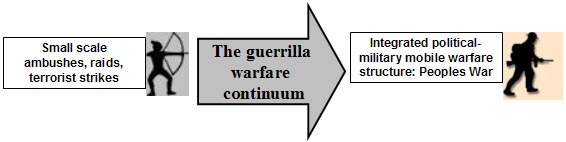

Guerrilla warfare can be conceived as a continuum.[1] On the low end are small-scale raids, ambushes and attacks. In ancient times these actions were often associated with smaller tribal polities fighting a larger empire, as in the struggle of Rome against the Spanish tribes for over a century. In the modern era they continue with the operations of terrorist, insurgent or revolutionary groups. The upper end is composed of a fully integrated political-military strategy, comprising both large and small units, engaging in constantly shifting mobile warfare, both on the low-end "guerrilla" scale, and that of large, mobile formations with modern arms. The latter phase came to fullest expression in the operations of Mao tse-Tung in China and Vo Nguyen Giap in Vietnam. In between are a large variety of situations - from the struggles of Palestinian guerrillas in the contemporary era, to Spanish and Portuguese irregulars operating with the conventional units of British General Wellington, during the Peninsular War against Napoleon.[2]

Modern guerrilla warfare at its fullest (high end) elaboration should be conceived of as an integrated process, complete with sophisticated doctrine, organization, specialist skills and propaganda capabilities. Guerrillas can operate as small, scattered bands of raiders, but they can also work side by side with regular forces, or combine for far ranging mobile operations in squad, platoon or battalion sizes, or even form conventional units. Based on their level of sophiscation and organization, they can shift between all these modes as the situation demands. Guerrilla warfare is flexible, not static.

Commando operations are not guerrilla warfare (Richard Taber, "The War of the Flea : Guerrilla Warfare, Theory and Practice." Paladin, London, 1977) while they lack the political goal. Commando troops, as the British commando, were a branch of the armed forces. Guerrilla warfare is the expression of Sun Tzu's Art of War, in contrast to Clausewitz's unlimited use of brute force. Guerrilla warfare is also distinguished from the small unit tactics used in screening or recon operations typical of conventional forces. It is also different from the activities of bandits, pirates or robbers. Such forces may use guerrilla-like tactics, but their primary purpose is booty, and not a clear political objective.

Tactics and strategy

Guerrilla tactics are based on intelligence, ambush, deception, sabotage, and espionage, undermining an authority through long, low-intensity confrontation. It can be quite successful against an unpopular foreign or local regime, as demonstrated by the Vietnam conflict. A guerrilla army may increase the cost of maintaining an occupation or a colonial presence above what the foreign power may wish to bear. Against a local regime, the guerrilla fighters may make governance impossible with terror strikes and sabotage, and even combination of forces to depose their local enemies in conventional battle. These tactics are useful in demoralizing an enemy, while raising the morale of the guerrillas. In many cases, guerrilla tactics allow a small force to hold off a much larger and better equipped enemy for a long time, as in Russia's Second Chechen War and the Second Seminole War fought in the swamps of Florida (United States of America). Guerrilla tactics and strategy are summarized below and are discussed extensively in standard reference works such as Mao's On Guerrilla Warfare.[1]

Three-phase Maoist model

Mao/Giap approach

Maoist theory of people's war divides warfare into three phases. In the first phase, the guerrillas gain the support of the population through the distribution of propaganda and attacks on the machinery of government. In the second phase, escalating attacks are made on the government's military and vital institutions. In the third phase, conventional fighting is used to seize cities, overthrow the government, and take control of the country. Mao's seminal work, On Guerrilla Warfare,[1] has been widely distributed and applied, nowhere more successfully than in Vietnam, under military leader and theorist Vo Nguyen Giap. Giap's "Peoples War, Peoples Army" [3] closely follows the Maoist three-stage approach, but with greater emphasis on flexible shifting between mobile and guerrilla warfare, and opportunities for a spontaneous "General Uprising" of the masses in conjunction with guerrilla forces.

Other variants

Such a phased approach does not apply to all guerrilla conflicts. In some cases, opposing conventional formations cannot be defeated in battle within any reasonable time scale. Small-scale attacks and sabotage however, can over time create an atmosphere of turmoil and chaos, (the "bloody mayhem" of Irish Leader Michael Collins) that is sufficient to force capitulation or extensive concessions from the opposing side. The Algerian War follows this pattern, as does the guerrilla operations leading to British withdrawal from in Cyprus. [4] Palestinian struggles against Israel seem to also follow this pattern, with a series of attritional attacks and international diplomatic pressure forcing concessions from the Israeli leadership.

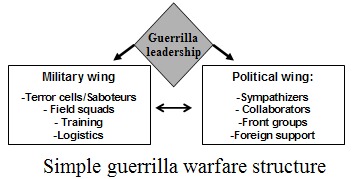

Organization

Guerrilla organization can range from small local rebel groups with a few dozen participants, to tens of thousands of fighters, deploying from tiny cells to formations of regimental strength. In most cases, there will be leadership aiming for a clear political objective. The organization will typically be structured into political and military wings, sometimes allowing the political leadership to claim "plausible denial" for military attacks.[5]The most fully elaborated guerrilla warfare structure is seen by the Chinese and Vietnamese communists during the revolutionary wars of East and Southeast Asia.[6]

Types of operations

Guerrilla operations typically include a variety of attacks on transportation routes, individual groups of police or military, installations and structures, economic enterprises, and targeted civilians. Attacking in small groups, using camouflage and often captured weapons of that enemy, the guerilla force can constantly keep pressure on its foes and diminish its numbers, while still allowing escape with relatively few casualties. The intention of such attacks is not only military but political, aiming to demoralize target populations or governments, or goading an overreaction that forces the population to take sides for or against the guerrillas. Examples range from the chopping off of limbs in various internal African rebellions, to the suicide bombings of Palestine and Sri Lanka, to sophisticated maneuvers by Viet Cong and NVA forces against military bases and formations.

Surprise and intelligence

For successful operations, surprise must be achieved by guerrillas. If the operation has been betrayed or compromised it is usually called off immediately. Intelligence is also extremely important, and detailed knowledge of the target's dispositions, weaponry and morale is gathered before any attack. Intelligence can be harvested in several ways. Collaborators and sympathizers will usually provide a steady flow of useful information. If working clandestinely, the guerrilla operative may disguise his membership in the insurgent operation, and use deception to ferret out needed data. Employment or enrollment as a student may be undertaken near the target zone, community organizations may be infiltrated, and even romantic relationships struck up as part of intelligence gathering.[6] Public sources of information are also invaluable to the guerrilla, from the flight schedules of targeted airlines, to public announcements of visiting foreign dignitaries, to Army Field Manuals. Modern computer access via the World Wide Web makes harvesting and collation of such data relatively easy. [7] The use of on the spot reconnaissance is integral to operational planning. Operatives will "case" or analyze a location or potential target in depth- cataloging routes of entry and exit, building structures, the location of phones and communication lines, presence of security personnel and a myriad of other factors. Finally intelligence is concerned with political factors- such as the occurrence of an election or the impact of the potential operation on civilian and enemy morale.

Relationships with the civil population

Relationships with civil populations are influenced by whether the guerrillas operate among a hostile or friendly population. A friendly population is of immense importance to guerrilla fighters, providing shelter, supplies, financing, intelligence and recruits. The "base of the people" is thus the key lifeline of the guerrilla movement. In the early stages of the Vietnam War, American officials "discovered that several thousand supposedly government-controlled 'fortified hamlets' were in fact controlled by Viet Cong guerrillas, who 'often used them for supply and rest havens'." [8] Popular mass support in a confined local area or country however is not always strictly necessary. Guerrillas and revolutionary groups can still operate using the protection of a friendly regime, drawing supplies, weapons, intellligence, local security and diplomatic cover. The Al Queda organization is an example of the latter type, drawing sympathizers and support primarily from the wide-ranging Muslim world, even after American attacks eliminated the umbrella of a friendly Taliban regime in Afghanistan.

An apathetic or hostile population makes life difficult for guerrillas and strenuous attempts are usually made to gain their support. These may involve not only persuasion, but a calculated policy of intimidation. Guerrilla forces may characterize a variety of operations as a liberation struggle, but this may or may not result in sufficient support from affected civilians. Other factors, including ethnic and religious hatreds, can make a simple national liberation claim untenable. Whatever the exact mix of persuasion or coercion used by guerrillas, relationships with civil populations are one of the most important factors in their success or failure. [9]

Use of terror

In some cases, the use of terror can be an aspect of guerrilla warfare. Terror is used to focus international attention on the guerrilla cause, liquidate opposition leaders, extort cash from targets, intimidate the general population, create economic losses, and keep followers and potential defectors in line. Such tactics may backfire and cause the civil population to withdraw its support, or to back countervailing forces against the guerrillas. [10]

Such situations occurred in Israel, where suicide bombings encouraged most Israeli opinion to take a harsh stand against Palestinian attackers, including general approval of "targeted killings" to liquidate enemy cells and leaders.[11] In the Philippines and Malaysia, communist terror strikes helped turn civilian opinion against the insurgents. In Peru and some other South American countries, civilian opinion at times backed the harsh countermeasures used by authoritarian regimes against revolutionary movements. (See the Peruvian regime of Alberto Fujimori for example).

Withdrawal

Guerrillas must plan carefully for withdrawal once an operation has been completed, or if it is going badly. The withdrawal phase is sometimes regarded as the most important part of a planned action, and to get entangled in a lengthy struggle with superior forces is usually fatal to insurgent, terrorist or revolutionary operatives. Withdrawal is usually accomplished using a variety of different routes and methods and may include quickly scouring the area for loose weapons, evidence cleanup, and disguise as peaceful civilians.[1] In the case of suicide operations, withdrawal considerations by successful attackers are moot, nevertheless such activity as eliminating traces of evidence, or hiding materials and supplies must be done.

Logistics

Guerrillas typically operate with a smaller logistical footprint compared to conventional formations, nevertheless their logistical activities can be elaborately organized. A primary consideration is to avoid dependence on fixed bases and depots which are comparatively easy for conventional units to locate and destroy. Mobility and speed are the keys and wherever possible, the guerrilla must live off the land, or draw support from the civil population in which he is embedded. In this sense, "the people" become the guerrillas supply base.[1] Financing of both terrorist and guerrilla activities ranges from direct individual contributions (voluntary or non-voluntary), and actual operation of business enterprises by insurgent operatives, to bank robberies, kidnappings and complex financial networks based on kin, ethnic and religious affiliation (such as that used by modern Jihadist/Jihad organizations).

Permanent and semi-permanent bases form part of the guerrilla logistical structure, usually located in remote areas or in cross-border sanctuaries sheltered by friendly regimes.[1][6] These can be quite elaborate, as in the tough VC/NVA fortified base camps and tunnel complexes encountered by US forces during the Vietnam War. Their importance can be seen by the hard fighting sometimes engaged in by communist forces to protect these sites. However when it became clear that defense was untenable, communist units typically withdrew without sentiment.

Terrain

Guerrilla warfare is often associated with a rural setting, and this is indeed the case with the definitive operations of Mao and Giap, the mujahadeen of Afghanistan, the Ejército Guerrillero de los Pobres (EGP) of Guatemala, the Contras of Nicaragua, and the FMLN of El Salvador. Guerrillas however have successfully operated in urban settings as demonstrated in places like Argentina, Northern Ireland and Cyprus. In those cases, guerrillas rely on a friendly population to provide supplies and intelligence. Rural guerrillas prefer to operate in regions providing plenty of cover and concealment, especially heavily forested and mountainous areas. Urban guerrillas, rather than melting into the mountains and jungles, blend into the population and are also dependent on a support base among the people. Rooting guerrillas out of both types of areas can be difficult.

Foreign support and sanctuaries

Foreign support in the form of soldiers, weapons, sanctuary, or statements of sympathy for the guerrillas is not strictly necessary, but it can greatly increase the chances of an insurgent victory.[6] Foreign diplomatic support may bring the guerrilla cause to international attention, putting pressure on local opponents to make concessions, or garnering sympathetic support and material assistance. Foreign sanctuaries can add heavily to guerrilla chances, furnishing weapons, supplies, materials and training bases. Such shelter can benefit from international law, particularly if the sponsoring government is successful in concealing its support and in claiming "plausible denial" for attacks by operatives based in its territory.

The VC and NVA made extensive use of such international sanctuaries during their conflict, and the complex of trails, way-stations and bases snaking through Laos and Cambodia, the famous Ho Chi Minh Trail, was the logistical lifeline that sustained their forces in the South. Another case in point is the Mukti Bahini guerrillas who fought alongside the Indian Army in the 14-day Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971 against Pakistan that resulted in the creation of the state of Bangladesh. In the post-Vietnam era, the Al Queda organization also made effective use of remote territories, such as Afghanistan under the Taliban regime, to plan and execute its operations. This foreign sanctuary eventually broke down with American attacks against the Taliban and Al Queda, but not before operatives perpetrated the September 11, 2001 attacks.

Guerrilla initiative and combat intensity

Able to choose the time and place to strike, guerrilla fighters will usually possess the tactical initiative and the element of surprise. Planning for an operation may take weeks, months or even years, with a constant series of cancellations and restarts as the situation changes.[6] Careful rehearsals and "dry runs" are usually conducted to work out problems and details. Many guerrilla strikes are not undertaken unless clear numerical superiority can be achieved in the target area, a pattern typical of VC/NVA and other "Peoples War" operations. Individual suicide bomb attacks offer another pattern, typically involving only the individual bomber and his support team, but these too are spread or metered out based on prevailing capabilities and political winds.

Whatever approach is used, the guerrilla holds the initiative, and can prolong his survival though varying the intensity of combat. This means that attacks are spread out over quite a range of time, from weeks to years. During the interim periods, the guerrilla can rebuild, resupply and plan. In the Vietnam War, most communist units (including mobile NVA regulars using guerrilla tactics) spent only a few days a month fighting. While they might be forced into an unwanted battle by an enemy sweep, most of the time was spent in training, intelligence gathering, political and civic infiltration, propaganda indoctrination, construction of fortifications, or foraging for supplies and food.[6] The large numbers of such groups striking at different times however, gave the war its "around the clock" quality.

Counter-guerrilla warfare

Stopping guerrillas may be difficult because they, by definition, blend into their surroundings and try not to draw attention to themselves or engage in prolonged battles in which they could be overcome with conventional force. Lieutenant General Patrick Hughes (ret.) says, "Most soldiers who have engaged in counter-guerrilla warfare believe that an effective strategy cannot be based merely on defensive measures but rather must be tied to an aggressive offensive approach, taking the war to the guerrilla, denying them sanctuary and interdicting their support, stopping their ability to assemble and plan, and taking away their capability to act."[12] Countering guerrilla fighters requires great planning and military intelligence. Understanding the terrain on which one is fighting is key as this takes away the guerillas 'home-field' advantage and removes much of the risk of booby-traps and ambushes. Another key component to countering guerrilla fighters is to become friendly with the local population to the point of them being uncomfortable hiding and supporting the guerillas.

Guidelines

The widely distributed and influential work of Sir. Robert Thompson, counter-insurgency expert in Malaysia, offers several such guidelines. Thompson's underlying assumption is that of a country minimally committed to the rule of law and better governance. Numerous other regimes, however, give such considerations short shrift, and their counterguerrilla operations have involved mass murder, genocide, starvation and the massive spread of terror, torture and execution. The totalitarian regimes of Stalin and Hitler are classic examples, as are more modern conflicts in places like Afghanistan. In Afghanistan's anti-Mujahideen war for example, the Soviets implemented a ruthless policy of wastage and depopulation, driving over one third of the Afghan population into exile (over 5 million people), and carrying out widespread destruction of villages, granaries, crops, herds and irrigation systems, including the deadly and widespread mining of fields and pastures. The basic elements of Thompson's[13] moderate approach are:

- A viable competing vision that comprehensively mobilizes popular support.

- Reasonable concessions where necessary.

- Economy of force.

- Big unit action may sometimes be necessary.

- Mobility.

- Systematic intelligence effort.

- Methodical clear and hold.

- Careful deployment of mass popular forces and special units.

- Foreign assistance must be limited and carefully used.

Variants

Some writers on counter-insurgency warfare emphasize the more turbulent nature of today's guerilla warfare environment, where the clear political goals, parties and structures of such places as Vietnam, Malaysia, or El Salvador are not as prevalent. These writers point to numerous guerrilla conflicts that center around religious, ethnic or even criminal enterprise themes, and that do not lend themselves to the classic "national liberation" template. The wide availability of the Internet has also cause changes in the tempo and mode of guerrilla operations in such areas as coordination of strikes, leveraging of financing, recruitment, and media manipulation. While the classic guidelines still apply, today's anti-guerrilla forces need to accept a more disruptive, disorderly and ambiguous mode of operation.

Insurgents may not be seeking to overthrow the state, may have no coherent strategy or may pursue a faith-based approach difficult to counter with traditional methods. There may be numerous competing insurgencies in one theater, meaning that the counterinsurgent must control the overall environment rather than defeat a specific enemy. The actions of individuals and the propaganda effect of a subjective “single narrative” may far outweigh practical progress, rendering counterinsurgency even more non-linear and unpredictable than before. The counterinsurgent, not the insurgent, may initiate the conflict and represent the forces of revolutionary change. The economic relationship between insurgent and population may be diametrically opposed to classical theory. And insurgent tactics, based on exploiting the propaganda effects of urban bombing, may invalidate some classical tactics and render others, like patrolling, counterproductive under some circumstances. Thus, field evidence suggests, classical theory is necessary but not sufficient for success against contemporary insurgencies.[14]

Ethical dimensions

Civilians may be attacked or killed as punishment for alleged collaboration, or as a policy of intimidation and coercion. Such attacks are usually sanctioned by the guerrilla leadership with an eye towards the political objectives to be achieved. Attacks may be aimed to weaken civilian morale so that support for the guerrillas' opponents decreases. Civil wars, may also involve deliberate attacks against civilians, with both guerrilla groups and organized armies committing atrocities. Ethnic and religious feuds may involve widespread massacres and genocide as competing factions inflict massive violence on targeted civilian population.

Guerrillas in wars against foreign powers may direct their attacks at civilians, particularly if foreign forces are too strong to be confronted directly on a long term basis. In Vietnam, bombings and terror attacks against civilians were fairly common, and were often effective in demoralizing local opinion that supported the ruling regime and its American backers. While attacking an American base might involve lengthy planning and casualties, smaller scale terror strikes in the civilian sphere were easier to execute. Such attacks also had an effect on the international scale, demoralizing American opinion, and hastening a withdrawal.

In Iraq, most of the deaths since the 2003 US conquest have not been suffered by US troops but by civilians, as warring factions plunged the country into civil war based on ethnic and religious hostilities. Arguments vary on whether such turmoil will succeed in turning American opinion against the US troop deployment. However the use of attacks against civilians to create an atmosphere of chaos (and thus political advantage where the atmosphere causes foreign occupiers to withdraw or offer concessions), is well established in guerrilla and national liberation struggles. Claims and counterclaims of the morality of such attacks, or whether guerrillas should be classified as "terrorists" or "freedom fighters" are beyond the scope of this article. See Terrorism and Genocide for a more in-depth discussion of the moral and ethical implications of targeting civilians.

Guerrillas are in danger of not being recognized as lawful combatants because they may not wear a uniform, (to mingle with the local population), or their uniform and distinctive emblems may not be recognized as such by their opponents. Article 44, sections 3 and 4 of the 1977 First Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions, "relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts," does recognize combatants who, because of the nature of the conflict, do not wear uniforms as long as they carry their weapons openly during military operations. This gives non-uniformed guerrillas lawful combatant status against countries that have ratified this convention. However, the same protocol states in Article 37.1.c that "the feigning of civilian, non-combatant status" shall constitute perfidy and is prohibited by the Geneva Conventions.

Examples

Guerrilla tactics have been used with varying levels of success for hundreds of years and all over the world, from the Napoleonic Wars in Europe to the American Civil War, to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

In Europe

Over centuries of history, many guerrilla movements appeared in Europe to fight foreign occupation forces. The Fabian Strategy applied by the Roman Republic against Hannibal in the Second Punic War could be considered an early example of guerrilla tactics. After witnessing several disastrous defeats at the hands of Hannibal, the Roman dictator Fabius Maximus decided to modify traditional warfare methods. More often full-scale pitched campaigns were exchanged for small-scale skirmishes, sieges, sabotage attempts, assassinations and raiding parties. The Romans set aside the typical military doctrine of crushing the enemy in a single battle and initiated a successful, albeit unpopular, war of attrition against the Carthaginians that lasted for 14 years. In expanding their own Empire, the Romans encountered numerous examples of guerrilla resistance to their legions as well.

Mongols also faced guerrillas composed by armed peasants in Hungary after the Battle of Mohi. During The Deluge in Poland guerrilla tactics were applied. In the 19th century, peoples of the Balkans used guerrilla tactics to fight the Ottoman empire. In the 100 years war between England and France, commander Bertrand du Guesclin used guerrilla tactics to pester the English invaders. During the Scanian War, a pro-Danish guerrilla group known as the Snapphane fought against the Swedes. In 17th century Ireland, Irish irregulars called tories and rapparees used guerrilla warfare in the Irish Confederate Wars and the Williamite war in Ireland. The Finns guerrillas, sissis, fought against Russian occupation troops in the Great Northern War 1710-1721. The Russians retaliated brutally on civilian populace; the period is called Isoviha (Grand Hatred) in Finland.

In the Napoleonic Wars many of the armies lived off the land. This often led to some resistance by the local population if the army did not pay fair prices for produce they consumed. Usually this resistance was sporadic, and not very successful, so it is not classified as guerrilla action. In the Peninsular War, however, the British, encouraged by the spontaneous mass resistance in Spain against Napoleon, gave aid to the Spanish guerrillas who tied down tens of thousands of French troops. The continual losses of troops caused Napoleon to describe this conflict his "Spanish ulcer." The British gave this aid because it cost them much less than it would have done to equip British soldiers to face the French troops in conventional warfare. This was one of the most successful partisan wars in history and was where the word guerrilla was first used in this context. The Oxford English Dictionary lists Wellington as the oldest known source, speaking of "Guerrillas" in 1809.

American Revolutionary War

While the American Revolutionary War is often thought of as a guerrilla war, guerrilla tactics were uncommon, and almost all of the battles involved conventional set-piece battles. Some of the confusion may be due to the fact that generals George Washington and Nathaniel Greene successfully used a strategy of harassment and progressively grinding down British forces instead of seeking a decisive battle, in a classic example of asymmetric warfare. Nevertheless the theater tactics used by most of the American forces were those of conventional warfare. One of the exceptions was in the south, where the brunt of the war was upon militia forces who fought the enemy British troops and their Loyalist supporters, but used concealment, surprise, and other guerrilla tactics to much advantage. General Francis Marion of South Carolina, who often attacked the British at unexpected places and then faded into the swamps by the time the British were able to organized return fire, was named by them The Swamp Fox.

American Civil War

Irregular warfare in the American Civil War followed the patterns of irregular warfare in 19th century Europe. Structurally, irregular warfare can be divided into three different types conducted during the Civil War: 'People's War', 'partisan warfare', and 'raiding warfare'. The concept of 'People's war,' first described by Clausewitz in On War, was the closest example of a mass guerrilla movement in the era. In general, this type of irregular warfare was conducted in the hinterland of the Border States (Missouri, Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky, and northwestern Virginia), and was marked by a vicious neighbor against neighbor quality. One such example was the opposing irregular forces operating in Missouri and northern Arkansas from 1862 to 1865, most of which were pro-Confederate or pro-Union in name only and preyed on civilians and isolated military forces of both sides with little regard of politics. From these semi-organized guerrillas, several groups formed and were given some measure of legitimacy by their governments. Quantrill's Raiders, who terrorized pro-Union civilians and fought Federal troops in large areas of Missouri and Kansas, was one such unit. Another notorious unit, with debatable ties to the Confederate military, was led by Champ Ferguson along the Kentucky-Tennessee border. Ferguson became one of the only figures of Confederate cause to be executed after the war. Dozens of other small, localized bands terrorized the countryside throughout the border region during the war, bringing total war to the area that lasted until the end of the Civil War and, in some areas, beyond.[15]

South African War

Guerrilla tactics were used extensively by the forces of the Afrikaner republics in the Second Boer War in South Africa 1899-1902. After the British defeated the Boer armies in conventional warfare and occupied their capitals of Pretoria and Bloemfontein, Boer commandos reverted to mobile warfare. Units led by leaders such as Christian de Wet harassed slow-moving British columns and attacked railway lines and encampments. The Boers were almost all mounted and possessed long range magazine loaded rifles. This gave them the ability to attack quickly and cause many casualties before retreating rapidly when British reinforcements arrived. In the early period of the guerrilla war, Boer commandos could be very large, containing several thousand men and even field artillery. However, as their supplies of food and ammunition gave out, the Boers increasingly broke up into smaller units and relied on captured British arms and ammunition.

To counter these tactics, the British under Kitchener interned Boer civilians into concentration camps and built hundreds of blockhouses all over the Transvaal and Orange Free State. Eventually, the Boer guerrillas surrendered in 1902, but the British granted them generous terms in order to bring the war to an end. This showed how effective guerrilla tactics could be in extracting concessions from a militarily more powerful enemy.

Latin America

In the Mexican Revolution from 1910 to 1920, the populist revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata employed the use of predominately guerrilla tactics. His forces, composed entirely of peasant farmers turned soldiers, wore no uniform and would easily blend into the general population after an operation's completion. They would have young soldiers, called "dynamite boys," hurl cans filled with explosives into enemy barracks, and then a large number of lightly armed soldiers would emerge from the surrounding area to attack it. Although Zapata's forces met considerable success, his strategy backfired as government troops, unable to distinguish his soldiers from the normal population, waged a broad and brutal campaign against the latter.

In the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, Latin America had a number of urban guerrilla movements whose strategy was to destabilize regimes and provoke a counter-reaction by the military. The theory was that a harsh military regime would oppress the middle classes who would then support the guerrillas and create a popular uprising.

While these movements did destabilize governments, such as Argentina, Uruguay, Guatemala, and Peru to the point of military intervention, the military generally proceeded to completely wipe out the guerrilla movements, usually committing several atrocities among both civilians and armed insurgents in the process.

Several other left-wing guerrilla movements, often backed by Cuba and/or the Soviet Union, attempted to overthrow US-backed governments or right-wing military dictatorships. US-backed Contra guerrillas attempted to overthrow the left-wing elected Sandinista government of Nicaragua, though most of these groups should be considered mercenary juntas rather than rooted guerrillas.

Anglo-Irish War

The wars between Ireland and the British state, have been long and over the centuries have covered the full spectrum of the types of warfare. The Irish fought the first successful 20th century war of independence against the British Empire and the United Kingdom. After the military failure of the Easter Rising in 1916, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) resorted to guerrilla tactics involving both urban warfare and flying columns in the countryside during the Anglo-Irish War (Irish War of Independence) of 1919 to 1921. The subsequent Anglo-Irish Treaty created the Irish Free State of 26 counties as a dominion within the British Empire; the other 6 counties remained part of the UK. This partition of Ireland laid the seeds for later troubles.

World War II

In World War II, several guerrilla organisations (often known as resistance movements) operated in the countries occupied by Nazi Germany. These included the Polish Home Army, Slovak National Uprising, Soviet partisans (see also Russian Guerrilla Warfare of WWII), Yugoslav Partisans, Bulgarian NOVA, French resistance or Maquis, Italian partisans, ELAS and royalist forces in Greece. Many of these organisations received help from the Special Operations Executive (SOE) which along with the commandos was initiated by Winston Churchill to "set Europe ablaze." The SOE was originally designated as 'Section D' of MI6 but its aid to resistance movements to start fires clashed with MI6's primary role as an intelligence-gathering agency. When Britain was under threat of invasion, SOE trained Auxiliary Units to conduct guerrilla warfare in the event of invasion. Not only did SOE help the resistance to tie down many German units as garrison troops, so directly aiding the conventional war effort, but also guerrilla incidents in occupied countries were useful in the propaganda war, helping to repudiate German claims that the occupied countries were pacified and broadly on the side of the Germans. Despite these minor successes, many historians believe that the efficacy of the European resistance movements has been greatly exaggerated in popular novels, films and other media. Contrary to popular belief, the resistance groups were only able to seriously counter the German in areas that offered the protection of rugged terrain. In relatively flat, open areas, such as France, the resistance groups were all too vulnerable to decimation by German regulars and pro-German collaborationists. Only when operating in concert with conventional Allied units were the resistance groups to prove indispensable.

Post World War II Europe

After World War II, during the 1940s and 1950s, thousands of fighters in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania participated in unsuccessful guerrilla warfare against Soviet occupation.[16]

Vietnam War

Within the United States, the Vietnam War is commonly thought of as a guerrilla war. However, this is a simplification of a much more complex situation which followed the pattern outlined by Maoist theory.

The National Liberation Front (NLF), drawing its ranks from the North Vietnamese peasantry and working class, used guerrilla tactics in the early phases of the war. However, by 1965 when U.S. involvement escalated, the National Liberation Front was in the process of being supplanted by regular units of the North Vietnamese Army.

The NVA regiments organized along traditional military lines, were supplied via the Ho Chi Minh trail rather than living off the land, and had access to weapons such as tanks and artillery which are not normally used by guerrilla forces. Furthermore, parts of North Vietnam were "off-limits" by American bombardment for political reasons, giving the NVA personnel and their materiel a haven that does not usually exist for a guerrilla army.

Over time, more of the fighting was conducted by the North Vietnamese Army and the character of the war become increasingly conventional. The final offensive into South Vietnam in 1975 was a mostly conventional military operation in which guerrilla warfare played a minor, supporting role.

The Cu Chi Tunnels (Địa đạo Củ Chi) was a major base for guerrilla warfare during the Vietnam War. Located about 60km northwest of Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City), the Viet Cong used the complex system tunnels to hide and live during the days and come up to fight at nights.

Israel and the Palestinian Territories

European Jews fleeing from anti-Semitic violence (especially Russian pogroms) immigrated in increasing numbers to Palestine. When the British restricted Jewish immigration to the region (see White Paper of 1939), Jewish Palestinians began to use guerrilla warfare for two purposes: to bring in more Jewish refugees, and to turn the tide of British sentiment at home. Jewish groups such as the Lehi and the Irgun - many of whom had experience in the Warsaw Ghetto battles against the Nazis, fought British soldiers whenever they could, including the bombing of the King David Hotel.

The creation of the state of Israel might be considered one of the greatest achievements of guerrilla warfare. The Jewish forces were composed of spontaneous groups of civilians working without formal military structure, fighting the British Empire, which had just emerged victorious from World War II. Some of these groups were amalgamated into the Israel Defence Force and subsequently fought in the 1948 War of Independence.)

Palestinian groups, among them the Palestinian Liberation Army, soon initiated their own guerrilla warfare against the new Jewish state.

Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Kurdish Northern Iraq