Difference between revisions of "Freedom of Speech" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→History) |

|||

| (80 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}}{{2Copyedited}} | ||

{{Freedom}} | {{Freedom}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | '''Freedom of speech''' is the ability to speak without [[censorship]] or limitation. Also called '''freedom of expression,''' it refers not only to verbal speech but any act of communicating information or ideas, including [[publication]]s, [[broadcasting]], [[art]], [[advertising]], [[film]], and the [[Internet]]. Freedom of speech and freedom of expression are closely related to the concepts of [[freedom of thought]] and [[conscience]]. | |

| − | The right to freedom of speech is recognized as a human right under Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and | + | Freedom of speech is a key factor in the spread of information in contemporary society and can be a potent political force. Authoritarian regimes, both political and religious, thus seek to control its exercise through various means. However, unbridled free speech can negatively impact the rights of others. Thus, even in the most liberal democracies, the right to freedom of speech is not absolute, but is subject to certain restrictions. Limitations on freedom of speech are thus imposed on such practices as false advertising, "[[hate speech]]," [[obscenity]], incitement to [[riot]], revealing state secrets, and [[slander]]. Achieving a balance between the right to freedom of speech on the one hand and the need for national security, decency, truth, and goodness on the other hand sometimes creates a [[paradox]], especially in the context of large scale legal systems. |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | The right to freedom of speech was first constitutionally protected by the revolutionary French and American governments of the late eighteenth century. It is recognized today as a fundamental human right under Article 19 of the [[Universal Declaration of Human Rights]] and is enshrined in international [[human rights]] law in the [[International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights]] and various regional human rights documents. Often subject to disclaimers relating to the need to maintain "public order," freedom of speech remains a contentious issue throughout the world today. | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | + | Historically speaking, freedom of speech has come to be guaranteed as a human right only relatively recently. Ancient rulers generally tolerated freedom of expression only insofar as it did not threaten their own power or the religious authority of their [[priest]]s. Even the relatively free society of [[Athens]] famously put its greatest philosopher, [[Socrates]], to death for expressing ideas it deemed unacceptable. | |

| − | In | + | In the [[Judeo-Christian tradition]], the right to freedom of speech is also a relatively recent one, although the affirmation of one's faith in the face of [[persecution]] has a very long and famous history. Well known ancient cases include the persecution of Israelite [[prophets]] like [[Jeremiah]] and [[Hosea]], the crucifixion of [[Jesus]], and the [[martyrdom]] of numerous Christian [[saints]] for refusing to recant their faith. However, when ancient Jewish or Christian governments themselves held power, they rarely afforded freedom of speech to those of divergent belief. In the ancient [[Kingdom of Judah]], [[pagan]] religions were banned, while in the Christian [[Roman Empire]], both pagans, [[Jews]], and "[[heretic]]s" were often persecuted for publicly expressing their beliefs. |

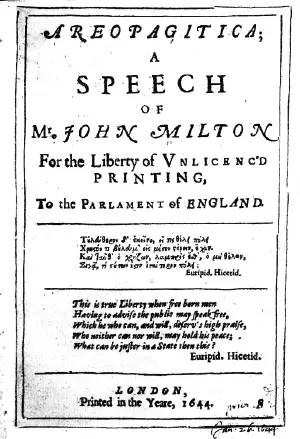

| − | + | [[Image:Areopagitica 1644bw gobeirne.png|thumb|300px|First page of the 1644 edition of [[John Milton|Milton]]'s [[Areopagitica]].]] | |

| − | + | In Islamic tradition, [[religious tolerance]] for Jews and Christians has always been official policy, but the right of these faiths to preach to Muslims was strictly banned. However, freedom of speech and thought as a more general principle was occasionally supported. A certain amount of [[academic freedom]] in Islamic universities also predated the evolution of this principle in Christian Europe. However, speech that criticized [[Islam]] and its [[prophet]] remained illegal, as it was thought to constitute [[blasphemy]]; and the expression of religious and other art was strictly limited, in accordance with the Islamic ban on images. | |

| − | + | In the West, meanwhile, expressing one's ideas openly was often a risky proposition, and the [[Catholic Church]] retained the position of official arbiter of truth, not only on matters of faith but of "natural philosophy" as well. The [[Protestant Reformation]] ended the Church's supposed monopoly on truth, affirming the right of individual Christians to interpret scripture more freely. On scientific matters, [[Galileo]] had been silenced by the [[Inquisition]] in [[Italy]] for endorsing the [[Copernicus|Copernican]] view of the universe, but [[Francis Bacon]] in [[England]] developed the idea that individuals had the right to express their own conclusions about the world based on reason and empirical observation. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In his ''[[Areopagitica]]'' (1644), the English poet and political writer [[John Milton]] reacted to an attempt by the republican parliament to prevent "seditious, unreliable, unreasonable, and unlicensed pamphlets." He advanced a number of arguments in defense of freedom of speech which anticipated the view which later came to be held almost universally. Milton argued that a nation's unity is created through blending individual differences rather than imposing [[homogeneity]] from above, and that the ability to explore the fullest range of ideas on a given issue is essential to any learning process. [[Censorship]] in political and religious speech, he held, is therefore a detriment to material progress and the health of the nation. | |

| + | [[Image:Declaration of Human Rights.jpg|thumb|300px|The [[Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen]].]] | ||

| − | + | Later in the seventeenth century, [[John Locke]] argued in his ''Two Treatises of Government'' that the proper function of the state is to ensure the [[human rights]] of its people. The [[Glorious Revolution]] of 1688 was inspired largely by Lockian ideals, including the principle of [[religious tolerance]] and freedom of speech in religious affairs. In 1776, the [[U.S. Declaration of Independence]] was the first official document to affirm the Lockian principle that the function of government is to protect liberty as a human right which is given not by the state, but by [[God]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The French [[Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen]], passed on August 26, 1789, declared: "No one shall be disquieted on account of his opinions, including his religious views, provided their manifestation does not disturb the public order established by law. The free communication of ideas and opinions is one of the most precious of the rights of man. Every citizen may, accordingly, speak, write, and print with freedom, but shall be responsible for such abuses of this freedom as shall be defined by law." | |

| − | + | The [[United States Bill of Rights]], introduced by [[James Madison]] in 1789 as a series of constitutional amendments, came into effect on December 15, 1791. Its First Amendment, unlike the French Declaration, placed no stated restriction on freedom of speech: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances." | |

| + | [[Image:EleanorRooseveltHumanRights.gif|thumb|left|350px| [[Eleanor Roosevelt]] holds a Spanish version of the UN's [[Universal Declaration of Human Rights]].]] | ||

| + | In the succeeding century, numerous governments adopted constitutions or legislative acts guaranteeing the right of freedom of speech to their citizens. A number of legal cases, meanwhile, began to address the issue of balancing the right to freedom of speech against the need for national security and moral order, as well as against other constitutionally guaranteed or implied individual rights. | ||

| − | + | After [[World War II]], the [[United Nations]] adopted the [[Universal Declaration of Human Rights]], guaranteeing the right of freedom of speech and conscience to all people. Its Article 19 reads: "Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers." Article 29, however, issued a disclaimer clarifying that human rights are subject to limitations for the "just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare in a democratic society." On the foundation of the Universal Declaration, the [[International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights]]—created in 1966 and implemented on March 23, 1976, guarantees "the right to hold opinions without interference. Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression." | |

| − | + | Similar provisions guaranteeing freedom of speech have been adopted by regional conventions throughout the world. The principle of freedom of speech is thus universally recognized today, although its interpretation and application as a matter of law varies widely. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Restrictions on free speech == | == Restrictions on free speech == | ||

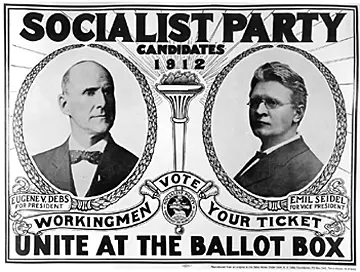

| − | [[Image:Debs campaign.jpg|thumb| | + | [[Image:Debs campaign.jpg|thumb|400px|[[Socialism|Socialist]] politician [[Eugene V. Debs]] (left) ran for [[President of the United States]] in 1912 and was later incarcerated for speaking against the draft during [[World War I]].]] |

| − | Ever since the first consideration of the idea of | + | Ever since the first formal consideration of the idea of freedom of speech, it has been recognized that this right is subject to restrictions and exceptions. Shortly after the first constitutional guarantees of freedom of speech were enacted in [[France]] and the [[United States]], limitations on this liberty were quickly imposed. In France, those who spoke out against the Revolution were subject to intimidation, arrest, and even execution, while in the U.S., the [[Sedition Act]] of 1798 made it a crime to publish "false, scandalous, and malicious writing" against the government or its officials. |

| − | + | No nation grants absolute freedom of speech to its citizens, for to do so would leave citizens unprotected from [[slander]] and the nation incapable of protecting its vital secrets. Restrictions on speech are thus sometimes clearly necessary, while other times, appeals to public order, national security, and other values are used to justify repression of speech that goes beyond established international norms. Restrictions of both types include laws against: | |

| − | + | * [[Defamation]] ([[slander]] and [[libel]] | |

| − | + | * Uttering [[threat]]s against persons | |

| − | * [[Defamation]] ( | + | * Lying in court ([[perjury]]) and [[contempt of court]] |

| − | + | * [[Hate speech]] based on [[race]], [[religion]], or [[sexual preference]] | |

| − | + | * [[Copyright infringement]], [[trademark]] violation, and publicizing [[trade secrets]] | |

| − | * [[ | + | * Revealing state secrets or classified information |

| − | * Lying in court ([[perjury]]) | + | * Lying that causes a crowd to panic |

| − | * | + | * "[[Fighting words]]" that incite a breach of the peace |

| − | * | + | * [[Sedition]], [[treason]]ous speech, and "encouragement of terrorism" |

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * [[ | ||

| − | |||

* [[Noise pollution]] | * [[Noise pollution]] | ||

| − | * | + | * [[Blasphemy]], [[heresy]], and attempts to convert a person from certain [[state religion]]s |

| − | + | * Distributing religious tracts where this is not permitted | |

| − | + | * [[Obscenity]], [[profanity]], and [[pornography]] | |

| − | + | * Speaking publicly in certain places without a permit | |

| − | + | * Wearing religious clothing or visibly praying in certain public schools | |

| − | + | * Racist statements, [[Holocaust denial]], and criticism of [[homosexuality]] | |

| − | * | + | * Publishing information on the Internet critical of one's nation |

| − | * [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Restrictions against obscenity and slander, though debated in terms of their definition, have virtually always remained in force as limitation on absolute freedom of speech. Another well known example of the need to restrict free speech is that of falsely "[[shouting fire in a crowded theater]]"—cited in ''[[Schenck v. United States]],'' a case relating to the distribution of anti-draft fliers during the [[World War I]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Speakers Corner London.jpg|thumb|400px|Muslim man exercises his right to freedom of speech at Speakers Corner in London]] |

| − | + | Standards of freedom of political speech have liberalized considerably in most democratic nations since [[World War II]], although calling for the violent overthrow of one's government can still constitute a crime. On the other hand, some countries that guarantee freedom of speech constitutionally still severely limit political, religious, or other speech in practice. Such double standards were particularly evident in the Communist regimes of the [[Cold War]], and were recently in evidence during the 2008 Summer [[Olympic Games]] in [[China]], where the government went to great lengths to suppress public protests of its [[human rights]] policies. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Regarding non-political and non-religious speech, during the second half of the twentieth century, the right of freedom of speech has been expanded in many jurisdictions to include the right to publish both literature with [[obscenity|obscene language]] and outright [[pornography]]. | |

| − | + | Freedom of religious speech is often severely restricted in [[Muslim]] countries where criticism of [[Islam]] is illegal under [[blasphemy]] laws and attempts to convert Muslims to another faith is also a criminal act. Even in Western nations, [[new religious movement]]s often face limitations on proselytizing and are sometimes accused of the crime of "mental coercion" in attempting to win new converts. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The degree to which a person or nation is committed to the principle of religious freedom is often thought to related to the degree to which one is willing to defend the right of someone to express ideas with which one strongly disagrees. Freedom of speech thus presents a [[paradox]]: It is most clearly present when those who would do away with it are exercising their right to it. | |

| − | |||

| − | Web sites which fall | + | == The Internet and freedom of speech== |

| + | The development of the [[Internet]] opened new possibilities for achieving a more universal freedom of speech. Web sites which fall afoul of government censors in one country are often re-hosted on a server in a country with no such restrictions. Given that the [[United States]] has in many respects one of the least restrictive governmental policies on freedom of speech, many of these websites re-host their content on an American server and thus escape censorship while remaining available to their target audience. However, many countries utilize filtering software sold by U.S. companies. | ||

| − | The [[ | + | The [[People's Republic of China|Chinese]] government has developed some of the most sophisticated forms of Internet censorship in order to control or eliminate access to information on sensitive topics such as the [[Tiananmen Square protests of 1989]], the [[Falun Gong]], [[Tibet]], [[Taiwan]], [[pornography]], and [[democracy]]. It has also enlisted the help of some American companies like [[Microsoft]] and [[Google]] who have subsequently been criticized by proponents of freedom of speech for cooperating with this restrictive measures. |

| − | + | ==The paradox of freedom of speech== | |

| + | When individuals assert their right to freedom of speech without considering the needs the larger community, tensions are created tempting the community to repress the freedom of speech of those individuals. This creates a paradox in which greater degrees of freedom of speech result in increasing social tensions and pressure to pass laws limiting speech which society deems irresponsible. At the same time, another paradox is created by the fact that unbridled freedom of speech can at times harm the rights of others, and thus needs to be balanced against those rights. | ||

| − | + | On the "liberal" side of the paradox of free speech is the example where the publication rights of [[pornography|pornographers]] and others deemed harmful to the social fabric are protected, while the expression of traditional moral and religious such as declaring [[homosexuality]] to be sinful is suppressed under the guise of laws against "hate speech." The "conservative" side of the paradox involves, for example, championing freedom on the one hand while suppressing the political views or privacy of others in the name of name of [[national security]]. | |

== See also == | == See also == | ||

* [[Censorship]] | * [[Censorship]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* [[Copyright]] | * [[Copyright]] | ||

| − | * [[ | + | * [[Religious freedom]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* [[Freedom of the press]] | * [[Freedom of the press]] | ||

| − | * [[ | + | * [[Universal Declaration of Human Rights]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References == | ==References == | ||

| − | + | * Elst, Michiel. ''Copyright, Freedom of Speech, and Cultural Policy in the Russian Federation''. Law in Eastern Europe, no. 53. Leiden: M. Nijhoff, 2005. ISBN 9789004140875 | |

| + | * Engdahl, Sylvia. ''Free Speech''. Detroit: Greenhaven Press, 2008. ISBN 9780737727913 | ||

| + | * Lewis, Anthony. ''Freedom for the Thought That We Hate: A Biography of the First Amendment''. Basic ideas. New York: Basic Books, 2010. ISBN 978-0465018192 | ||

| + | * Nsouli, Mona A., and Lokman I. Meho. ''Censorship in the Arab World: An Annotated Bibliography''. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2006. ISBN 9780810858695 | ||

| + | * Smolla, Rodney A. ''Free Speech in an Open Society''. New York: Knopf, 1992. ISBN 9780679407270 | ||

| + | * Zeno-Zencovich, Vincenzo. ''Freedom of Expression: A Critical and Comparative Analysis''. University of Texas at Austin studies in foreign and transnational law. Abingdon, OX: Routledge-Cavendish, 2008. ISBN 978-0415471558 | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| + | All links retrieved March 21, 2022. | ||

* [http://observer.guardian.co.uk/focus/story/0,,1702539,00.html Timeline: a history of free speech] | * [http://observer.guardian.co.uk/focus/story/0,,1702539,00.html Timeline: a history of free speech] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* [http://www.ifex.org International Freedom of Expression Exchange] | * [http://www.ifex.org International Freedom of Expression Exchange] | ||

| − | * [ | + | * [https://www.oas.org/en/topics/human_rights.asp Organization of American States - Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression] |

| − | + | * [https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/educational-resources/about-educational-outreach/activity-resources/what-does What Does Free Speech Mean?] ''US Courts'' | |

| − | * [ | + | * [https://www.aclu.org/issues/free-speech Free Speech] ''ACLU'' |

| − | + | * [https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/amendment-i/interps/266 | |

| − | * [ | + | Freedom of Speech and the Press] ''Constitution Center'' |

| − | * [ | + | * [https://www.history.com/topics/united-states-constitution/freedom-of-speech Freedom of Speech] ''History.com'' |

| − | + | * [https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/freedom-of-expression/ Freedom of Expression] ''Amnesty International'' | |

| − | * [ | ||

| − | * [ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:philosophy]] | [[Category:philosophy]] | ||

| + | [[Category:law]] | ||

| + | [[Category:history]] | ||

| + | [[Category:politics]] | ||

{{Credit|210859663}} | {{Credit|210859663}} | ||

Revision as of 20:08, 21 March 2022

| Part of a series on |

| Freedom |

| By concept |

|

Philosophical freedom |

| By form |

|---|

|

Academic |

| Other |

|

Censorship |

Freedom of speech is the ability to speak without censorship or limitation. Also called freedom of expression, it refers not only to verbal speech but any act of communicating information or ideas, including publications, broadcasting, art, advertising, film, and the Internet. Freedom of speech and freedom of expression are closely related to the concepts of freedom of thought and conscience.

Freedom of speech is a key factor in the spread of information in contemporary society and can be a potent political force. Authoritarian regimes, both political and religious, thus seek to control its exercise through various means. However, unbridled free speech can negatively impact the rights of others. Thus, even in the most liberal democracies, the right to freedom of speech is not absolute, but is subject to certain restrictions. Limitations on freedom of speech are thus imposed on such practices as false advertising, "hate speech," obscenity, incitement to riot, revealing state secrets, and slander. Achieving a balance between the right to freedom of speech on the one hand and the need for national security, decency, truth, and goodness on the other hand sometimes creates a paradox, especially in the context of large scale legal systems.

The right to freedom of speech was first constitutionally protected by the revolutionary French and American governments of the late eighteenth century. It is recognized today as a fundamental human right under Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and is enshrined in international human rights law in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and various regional human rights documents. Often subject to disclaimers relating to the need to maintain "public order," freedom of speech remains a contentious issue throughout the world today.

History

Historically speaking, freedom of speech has come to be guaranteed as a human right only relatively recently. Ancient rulers generally tolerated freedom of expression only insofar as it did not threaten their own power or the religious authority of their priests. Even the relatively free society of Athens famously put its greatest philosopher, Socrates, to death for expressing ideas it deemed unacceptable.

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, the right to freedom of speech is also a relatively recent one, although the affirmation of one's faith in the face of persecution has a very long and famous history. Well known ancient cases include the persecution of Israelite prophets like Jeremiah and Hosea, the crucifixion of Jesus, and the martyrdom of numerous Christian saints for refusing to recant their faith. However, when ancient Jewish or Christian governments themselves held power, they rarely afforded freedom of speech to those of divergent belief. In the ancient Kingdom of Judah, pagan religions were banned, while in the Christian Roman Empire, both pagans, Jews, and "heretics" were often persecuted for publicly expressing their beliefs.

In Islamic tradition, religious tolerance for Jews and Christians has always been official policy, but the right of these faiths to preach to Muslims was strictly banned. However, freedom of speech and thought as a more general principle was occasionally supported. A certain amount of academic freedom in Islamic universities also predated the evolution of this principle in Christian Europe. However, speech that criticized Islam and its prophet remained illegal, as it was thought to constitute blasphemy; and the expression of religious and other art was strictly limited, in accordance with the Islamic ban on images.

In the West, meanwhile, expressing one's ideas openly was often a risky proposition, and the Catholic Church retained the position of official arbiter of truth, not only on matters of faith but of "natural philosophy" as well. The Protestant Reformation ended the Church's supposed monopoly on truth, affirming the right of individual Christians to interpret scripture more freely. On scientific matters, Galileo had been silenced by the Inquisition in Italy for endorsing the Copernican view of the universe, but Francis Bacon in England developed the idea that individuals had the right to express their own conclusions about the world based on reason and empirical observation.

In his Areopagitica (1644), the English poet and political writer John Milton reacted to an attempt by the republican parliament to prevent "seditious, unreliable, unreasonable, and unlicensed pamphlets." He advanced a number of arguments in defense of freedom of speech which anticipated the view which later came to be held almost universally. Milton argued that a nation's unity is created through blending individual differences rather than imposing homogeneity from above, and that the ability to explore the fullest range of ideas on a given issue is essential to any learning process. Censorship in political and religious speech, he held, is therefore a detriment to material progress and the health of the nation.

Later in the seventeenth century, John Locke argued in his Two Treatises of Government that the proper function of the state is to ensure the human rights of its people. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 was inspired largely by Lockian ideals, including the principle of religious tolerance and freedom of speech in religious affairs. In 1776, the U.S. Declaration of Independence was the first official document to affirm the Lockian principle that the function of government is to protect liberty as a human right which is given not by the state, but by God.

The French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, passed on August 26, 1789, declared: "No one shall be disquieted on account of his opinions, including his religious views, provided their manifestation does not disturb the public order established by law. The free communication of ideas and opinions is one of the most precious of the rights of man. Every citizen may, accordingly, speak, write, and print with freedom, but shall be responsible for such abuses of this freedom as shall be defined by law."

The United States Bill of Rights, introduced by James Madison in 1789 as a series of constitutional amendments, came into effect on December 15, 1791. Its First Amendment, unlike the French Declaration, placed no stated restriction on freedom of speech: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances."

In the succeeding century, numerous governments adopted constitutions or legislative acts guaranteeing the right of freedom of speech to their citizens. A number of legal cases, meanwhile, began to address the issue of balancing the right to freedom of speech against the need for national security and moral order, as well as against other constitutionally guaranteed or implied individual rights.

After World War II, the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, guaranteeing the right of freedom of speech and conscience to all people. Its Article 19 reads: "Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers." Article 29, however, issued a disclaimer clarifying that human rights are subject to limitations for the "just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare in a democratic society." On the foundation of the Universal Declaration, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights—created in 1966 and implemented on March 23, 1976, guarantees "the right to hold opinions without interference. Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression."

Similar provisions guaranteeing freedom of speech have been adopted by regional conventions throughout the world. The principle of freedom of speech is thus universally recognized today, although its interpretation and application as a matter of law varies widely.

Restrictions on free speech

Ever since the first formal consideration of the idea of freedom of speech, it has been recognized that this right is subject to restrictions and exceptions. Shortly after the first constitutional guarantees of freedom of speech were enacted in France and the United States, limitations on this liberty were quickly imposed. In France, those who spoke out against the Revolution were subject to intimidation, arrest, and even execution, while in the U.S., the Sedition Act of 1798 made it a crime to publish "false, scandalous, and malicious writing" against the government or its officials.

No nation grants absolute freedom of speech to its citizens, for to do so would leave citizens unprotected from slander and the nation incapable of protecting its vital secrets. Restrictions on speech are thus sometimes clearly necessary, while other times, appeals to public order, national security, and other values are used to justify repression of speech that goes beyond established international norms. Restrictions of both types include laws against:

- Defamation (slander and libel

- Uttering threats against persons

- Lying in court (perjury) and contempt of court

- Hate speech based on race, religion, or sexual preference

- Copyright infringement, trademark violation, and publicizing trade secrets

- Revealing state secrets or classified information

- Lying that causes a crowd to panic

- "Fighting words" that incite a breach of the peace

- Sedition, treasonous speech, and "encouragement of terrorism"

- Noise pollution

- Blasphemy, heresy, and attempts to convert a person from certain state religions

- Distributing religious tracts where this is not permitted

- Obscenity, profanity, and pornography

- Speaking publicly in certain places without a permit

- Wearing religious clothing or visibly praying in certain public schools

- Racist statements, Holocaust denial, and criticism of homosexuality

- Publishing information on the Internet critical of one's nation

Restrictions against obscenity and slander, though debated in terms of their definition, have virtually always remained in force as limitation on absolute freedom of speech. Another well known example of the need to restrict free speech is that of falsely "shouting fire in a crowded theater"—cited in Schenck v. United States, a case relating to the distribution of anti-draft fliers during the World War I.

Standards of freedom of political speech have liberalized considerably in most democratic nations since World War II, although calling for the violent overthrow of one's government can still constitute a crime. On the other hand, some countries that guarantee freedom of speech constitutionally still severely limit political, religious, or other speech in practice. Such double standards were particularly evident in the Communist regimes of the Cold War, and were recently in evidence during the 2008 Summer Olympic Games in China, where the government went to great lengths to suppress public protests of its human rights policies.

Regarding non-political and non-religious speech, during the second half of the twentieth century, the right of freedom of speech has been expanded in many jurisdictions to include the right to publish both literature with obscene language and outright pornography.

Freedom of religious speech is often severely restricted in Muslim countries where criticism of Islam is illegal under blasphemy laws and attempts to convert Muslims to another faith is also a criminal act. Even in Western nations, new religious movements often face limitations on proselytizing and are sometimes accused of the crime of "mental coercion" in attempting to win new converts.

The degree to which a person or nation is committed to the principle of religious freedom is often thought to related to the degree to which one is willing to defend the right of someone to express ideas with which one strongly disagrees. Freedom of speech thus presents a paradox: It is most clearly present when those who would do away with it are exercising their right to it.

The Internet and freedom of speech

The development of the Internet opened new possibilities for achieving a more universal freedom of speech. Web sites which fall afoul of government censors in one country are often re-hosted on a server in a country with no such restrictions. Given that the United States has in many respects one of the least restrictive governmental policies on freedom of speech, many of these websites re-host their content on an American server and thus escape censorship while remaining available to their target audience. However, many countries utilize filtering software sold by U.S. companies.

The Chinese government has developed some of the most sophisticated forms of Internet censorship in order to control or eliminate access to information on sensitive topics such as the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, the Falun Gong, Tibet, Taiwan, pornography, and democracy. It has also enlisted the help of some American companies like Microsoft and Google who have subsequently been criticized by proponents of freedom of speech for cooperating with this restrictive measures.

The paradox of freedom of speech

When individuals assert their right to freedom of speech without considering the needs the larger community, tensions are created tempting the community to repress the freedom of speech of those individuals. This creates a paradox in which greater degrees of freedom of speech result in increasing social tensions and pressure to pass laws limiting speech which society deems irresponsible. At the same time, another paradox is created by the fact that unbridled freedom of speech can at times harm the rights of others, and thus needs to be balanced against those rights.

On the "liberal" side of the paradox of free speech is the example where the publication rights of pornographers and others deemed harmful to the social fabric are protected, while the expression of traditional moral and religious such as declaring homosexuality to be sinful is suppressed under the guise of laws against "hate speech." The "conservative" side of the paradox involves, for example, championing freedom on the one hand while suppressing the political views or privacy of others in the name of name of national security.

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Elst, Michiel. Copyright, Freedom of Speech, and Cultural Policy in the Russian Federation. Law in Eastern Europe, no. 53. Leiden: M. Nijhoff, 2005. ISBN 9789004140875

- Engdahl, Sylvia. Free Speech. Detroit: Greenhaven Press, 2008. ISBN 9780737727913

- Lewis, Anthony. Freedom for the Thought That We Hate: A Biography of the First Amendment. Basic ideas. New York: Basic Books, 2010. ISBN 978-0465018192

- Nsouli, Mona A., and Lokman I. Meho. Censorship in the Arab World: An Annotated Bibliography. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2006. ISBN 9780810858695

- Smolla, Rodney A. Free Speech in an Open Society. New York: Knopf, 1992. ISBN 9780679407270

- Zeno-Zencovich, Vincenzo. Freedom of Expression: A Critical and Comparative Analysis. University of Texas at Austin studies in foreign and transnational law. Abingdon, OX: Routledge-Cavendish, 2008. ISBN 978-0415471558

External links

All links retrieved March 21, 2022.

- Timeline: a history of free speech

- International Freedom of Expression Exchange

- Organization of American States - Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression

- What Does Free Speech Mean? US Courts

- Free Speech ACLU

- [https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/amendment-i/interps/266

Freedom of Speech and the Press] Constitution Center

- Freedom of Speech History.com

- Freedom of Expression Amnesty International

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.