Difference between revisions of "Free space" - New World Encyclopedia

| (16 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Ready}} | + | {{Ready}}{{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{copyedited}} |

{{Electromagnetism|cTopic=[[Classical electromagnetism|Electrodynamics]]}} | {{Electromagnetism|cTopic=[[Classical electromagnetism|Electrodynamics]]}} | ||

| − | |||

| + | In [[classical physics]], '''free space,''' sometimes called the '''vacuum of free space''', refers to a region of [[space]] where there is a theoretically "perfect" [[vacuum]]. It is a concept of [[electromagnetic theory]]. This concept is an abstraction from nature, a baseline or reference state that is unattainable in practice, like the [[absolute zero]] of temperature. The definitions of the [[ampere]] and [[meter]] [[SI units]] are based on measurements corrected to refer to free space. In the theory of [[quantum mechanics]], the "quantum vacuum" is not entirely empty but contains electromagnetic waves and particles that pop in and out of existence. The differences between free space and the quantum vacuum are predicted to be very small. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

==Properties of ''free space''== | ==Properties of ''free space''== | ||

| − | + | Free space is characterized by the ''defined'' value of the parameter μ<sub><small>0</small></sub> known as the ''[[permeability of free space]]'' or the ''magnetic constant,''<ref>NIST, [http://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Value?mu0 magnetic constant.] Retrieved January 26, 2009.</ref> and the ''defined'' value of the parameter ε<sub><small>0</small></sub> called the ''[[permittivity of free space]]'' or the ''electric constant''.<ref>NIST, [http://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Value?ep0 electric constant.] Retrieved January 26, 2009.</ref> | |

| − | </ref> | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | Maxwell viewed permeability as being a quantity related to density, and he viewed dielectric constant, the reciprocal of permittivity, as being a quantity related to transverse elasticity. He used these quantities in Newton's equation for the speed of sound to obtain a wave speed equal to the speed of light ''c<sub><small>0</small></sub>''. This famous calculation concludes around equation (136) in Part III of his 1861 paper "On Physical Lines of Force" with the estimate that ''c<sub><small>0</small></sub>''=195,647 miles per second. The logical status of the electric and magnetic constant in SI units has shifted, however, and the velocity of light is now a defined value, not a measured or observed value. See the related articles on [[meter]], [[ampere (unit)]] and [[speed of light]].<ref>J.C. Maxwell, [http://vacuum-physics.com/Maxwell/maxwell_oplf.pdf On Physical Lines of Force,] vacuum-physics.com. Retrieved January 10, 2009.</ref><ref>Gillespie (2008), 14.</ref> The parameter ε<sub>0</sub> also enters the expression for the [[fine-structure constant]] usually denoted by α,<ref>NIST, [http://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Value?alph| fine structure constant α]. Retrieved January 26, 2009.</ref> which characterizes the strength of the [[electromagnetic interaction]]. | |

| − | + | In the reference state of free space, according to Maxwell's equations, [[electromagnetic wave]]s, such as [[radio wave]]s and [[visible light]] (among other [[electromagnetic spectrum]] frequencies) propagate at the ''defined'' [[Speed_of_light#Speed_of_light_set_by_definition|speed of light]], ''c<sub>0</sub>''.<ref>NIST, [http://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Value?c| speed of light in vacuum: c, c<sub>0</sub>.] Retrieved January 26, 2009.</ref> According to the [[Special relativity|theory of special relativity]], this speed is independent of the speed of the observer or of the source of the waves. The electric and magnetic fields in these waves are related by the ''defined'' value of the [[characteristic impedance of vacuum]] ''Z<sub>0</sub>''.<ref>NIST, [http://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Value?z0|characteristic impedance of vacuum: Z<sub>0</sub>]. Retrieved January 26, 2009.</ref> | |

| + | |||

| + | In addition, in this reference state, the principle of [[linear superposition]] of potentials and fields holds. For example, the electric potential generated by two charges is the simple addition of the potentials generated by each charge in isolation.<ref name=Jackson1>Jackson (1999), 10, 13.</ref> | ||

==What is the ''vacuum''?== | ==What is the ''vacuum''?== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The | + | The ideal ''vacuum of free space'' is not the same as a physically obtainable ''vacuum''. Physicists use the term "vacuum" in several ways. One use is to discuss ideal test results that would occur in a "perfect vacuum," which physicists simply call ''vacuum'' or ''free space'' in this context. Physicists use the term '''partial vacuum''' to refer to the imperfect vacuum realizable in practice. The term "partial vacuum" suggests a space where the [[pressure]] is low but not zero. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | === Quantum vacuum === | |

| + | Today, the classical concept of vacuum as a simple void has been replaced by the ''quantum vacuum,'' separating "free space" still further from the earlier concept of a perfect vacuum. Quantum vacuum or the [[vacuum state]] is not empty.<ref name=Dittrich>Dittrich and Gies (2000).</ref> An approximate meaning is as follows:<ref name=Kane>Kane (2000), Appendix A, 149 ff.</ref> | ||

| + | <blockquote>Quantum vacuum describes a region devoid of real particles in its lowest energy state.</blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lambrecht<ref name=Lambrecht>Lambrecht (2002), 197.</ref> has noted that the quantum vacuum is "by no means a simple empty space," and Ray<ref name=Ray>Ray (1991), 205.</ref> has observed that "it is a mistake to think of any physical vacuum as some absolutely empty void." | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to quantum mechanics, empty space (the "vacuum") is not truly empty but instead contains fleeting electromagnetic waves and particles that pop in and out of existence.<ref>AIP, [http://www.aip.org/pnu/1996/split/pnu300-3.htm AIP Physics News Update.] Retrieved January 10, 2009.</ref> One measurable result of these ephemeral occurrences is the [[Casimir effect]].<ref>APS, [http://focus.aps.org/story/v2/st28 Physical Review Focus Dec,] focus.aps.org. Retrieved January 10, 2009.</ref><ref>F. Capasso, J.N. Munday, D. Iannuzzi, and H.B. Chen, 2007, [https://www.editorial.seas.harvard.edu/capasso/publications/Capasso_STJQE_13_400_2007.pdf Casimir forces and quantum electrodynamical torques: Physics and nanomechanics,] Harvard University. Retrieved January 10, 2009.</ref> Other examples are [[spontaneous emission]]<ref name=Yokoyama,>Yokoyama, and Ujihara (1995), 6.</ref><ref name=Fain>Fain (2000), §4.4; 113ff.</ref><ref name=Scully1>Scully and Zubairy (1997), §1.5.2; 22–23</ref> and the [[Lamb shift]].<ref name=Scully2>Scully, and Zubairy (1997), 13-16.</ref> Related to these differences, quantum vacuum differs from free space in exhibiting nonlinearity in the presence of strong electric or magnetic fields (violation of linear superposition). | ||

| − | + | Even in classical physics, it was realized that the vacuum must have a field-dependent permittivity in the strong fields found near point charges.<ref>M. Born and L. Infeld, ''Proc. Royal Soc. London'' A144 (1934):425.</ref><ref name=Jackson>Jackson (1999), 10–12.</ref> These field-dependent properties of the quantum vacuum continue to be an active area of research.<ref>A. Di Piazza, K. Z. Hatsagortsyan, and C. H. Keitel, 2006, [http://arxiv.org/abs/hep-ph/0602039v2 Light diffraction by a strong standing electromagnetic wave,] ''Phys. Rev. Lett.''; Gies, Holger, Joerg Jaeckel, and Andreas Ringwald, 2006, [http://arxiv.org/abs/hep-ph/0607118v1 Polarized light propagating in a magnetic field as a probe for millicharged fermions,] ''Phys. Rev. Letts.'' 97. Retrieved January 10, 2009.</ref><ref>Saunders and Brown (1991) and Genz (2002).</ref> | |

| − | + | At present, even the meaning of the quantum vacuum state is not settled. For example, what constitutes a "particle" depends on the gravitational state of the observer.<ref name=Fulling>Fulling (1989), 259.</ref><ref name=Cao>Cao (1999), 179.</ref> Speculation abounds on the role of the quantum vacuum in an expanding universe. In addition, the quantum vacuum may exhibit spontaneous [[symmetry breaking]].<ref name=Woit>Woit, 2006.</ref> | |

| − | In short, realization of the ideal of "free space" is not just a matter of achieving low pressure, as the term ''partial vacuum'' suggests. In fact, "free space" is an abstraction from nature, a baseline or reference state, that is unattainable in practice.<ref name=Correa> | + | The discrepancies between free space and the quantum vacuum are predicted to be very small, and to date there is no suggestion that these uncertainties affect the use of [[SI units]], the implementation of which is predicated on the undisputed predictions of [[Precision tests of QED|quantum electrodynamics]].<ref name=Genz>Genz (2002), 247.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | In short, realization of the ideal of "free space" is not just a matter of achieving low pressure, as the term ''partial vacuum'' suggests. In fact, "free space" is an abstraction from nature, a baseline or reference state, that is unattainable in practice.<ref name=Correa>Paulo N. Correa and Alexandra N. Correa, [http://www.aetherometry.com/publications/direct/AS4-02.pdf The Sagnac and Michelson-Gale-Pearson Experiments: The tribulations of general relativity with respect to rotation.] Retrieved January 10, 2009.</ref> | ||

==Realization of free space in a laboratory== | ==Realization of free space in a laboratory== | ||

| − | By "realization" is meant the [[reduction to practice]], or experimental embodiment, of the term "free space," for example, a ''partial vacuum''. What is the [[operational definition]] of free space? Although in principle ''free space'' is unattainable, like the [[absolute zero]] of temperature, the [[SI units]] are referred to ''free space'' | + | By "realization" is meant the [[reduction to practice]], or experimental embodiment, of the term "free space," for example, a ''partial vacuum''. What is the [[operational definition]] of free space? Although in principle ''free space'' is unattainable, like the [[absolute zero]] of temperature, the [[SI units]] are referred to ''free space,'' and so an estimate of the necessary correction to a real measurement is needed. An example might be a correction for non-zero pressure of a partial vacuum. Regarding measurements taken in a real environment (for example, partial vacuum) that are to be related to "free space," the [[CIPM]] cautions that:<ref name=CIPM>NIST, [http://physics.nist.gov/Pubs/SP330/sp330.pdf CIPM adopted Recommendation 1 (CI-1983)]. physics.nist.gov. Retrieved January 10, 2009.</ref> |

| − | <blockquote> | + | <blockquote>In all cases any necessary corrections be applied to take account of actual conditions such as diffraction, gravitation or imperfection in the vacuum.</blockquote> |

| − | In practice, a partial vacuum can be produced in the laboratory that is a very good realization of free space. Some of the issues involved in obtaining a high vacuum are described in the article on [[ultra high vacuum]]. The lowest measurable pressure today is about 10<sup>−11</sup> Pa.<ref name=Rozanov>Rozanov | + | In practice, a partial vacuum can be produced in the laboratory that is a very good realization of free space. Some of the issues involved in obtaining a high vacuum are described in the article on [[ultra high vacuum]]. The lowest measurable pressure today is about 10<sup>−11</sup> Pa.<ref name=Rozanov>Rozanov and Hablanian (2002), 80.</ref> (The abbreviation Pa stands for the unit [[Pascal (unit)|pascal]], 1 pascal = 1 N/m<sup>2</sup>.) |

==Realization of free space in outer space== | ==Realization of free space in outer space== | ||

| − | + | Although it is only a partial vacuum, [[outer space]] contains such sparse matter that the pressure of interstellar space is on the order of 10 [[Pascal (unit)|pPa]] (1×10<sup>−11</sup> Pa).<ref>MiMi Zheng, [http://hypertextbook.com/facts/2002/MimiZheng.shtml Pressure in Outer Space,] The Physics Factbook. Retrieved January 10, 2009.</ref> For comparison, the pressure at sea level (as defined in the unit of [[Atmosphere (unit)|atmospheric pressure]]) is about 101 kPa (1×10<sup>5</sup> Pa). The gases in outer space are not uniformly distributed, of course. The density of hydrogen in our galaxy is estimated at 1 hydrogen atom/cm<sup>3</sup>.<ref name=Wynn-Williams>Wynn-Williams (1992), 38.</ref> | |

| − | In the partial vacuum of [[outer space]], there are [[density|small quantities]] of [[matter]] (mostly hydrogen), [[cosmic dust]] and [[cosmic noise]]. See [[intergalactic space]]. In addition, there is a [[cosmic microwave background]] with a temperature of 2.725 K, which implies a photon density of about 400 /cm<sup>3</sup>.<ref> | + | In the partial vacuum of [[outer space]], there are [[density|small quantities]] of [[matter]] (mostly hydrogen), [[cosmic dust]] and [[cosmic noise]]. See [[intergalactic space]]. In addition, there is a [[cosmic microwave background]] with a temperature of 2.725 K, which implies a photon density of about 400 /cm<sup>3</sup>.<ref>Martin J. Rees, [http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v275/n5675/abs/275035a0.html Origin of pregalactic microwave background,] ''[[Nature]]'' 275: 35–37.</ref> (This background temperature depends upon the gravitational state of the observer. See [[Unruh effect#Calculations|Unruh effect]].) |

The density of the [[interplanetary medium]] and [[interstellar medium]], though, is extremely low; for many applications negligible error is introduced by treating the interplanetary and interstellar regions as "free space." | The density of the [[interplanetary medium]] and [[interstellar medium]], though, is extremely low; for many applications negligible error is introduced by treating the interplanetary and interstellar regions as "free space." | ||

| − | == | + | == U.S. Patent Office interpretation of free space== |

| − | The [[United States Patent Office]] defines | + | The [[United States Patent Office]] defines ''"free space"'' in a number of ways. For radio and radar applications the definition is "''space where the movement of energy in any direction is substantially unimpeded, such as the atmosphere, the ocean, or the earth''" (Glossary in US Patent Class 342, Class Notes).<ref>USPTO, [http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/ac/ido/oeip/taf/def/342.htm Classification Definitions,] U.S. Patent Classification System, June 30, 2000. Retrieved January 10, 2009.</ref> This definition does not match the technical definitions of free space outlined above, which do not refer to a medium. |

| − | Another US Patent Office interpretation is Subclass 310: Communication over free space, where the definition is " | + | Another US Patent Office interpretation is Subclass 310: Communication over free space, where the definition is "a medium which is not a wire or a waveguide."<ref>USPTO, [http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/ac/ido/oeip/taf/def/370.htm#310 Subclass 310: Communication over free space.] Retrieved January 10, 2009.</ref> This definition bears little if any relation to other technical definitions of free space outlined above. |

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| − | |||

* [[Electromagnetism]] | * [[Electromagnetism]] | ||

* [[Elementary particle]] | * [[Elementary particle]] | ||

| Line 52: | Line 58: | ||

* [[Speed of light]] | * [[Speed of light]] | ||

* [[SI units]] | * [[SI units]] | ||

| − | |||

* [[Vacuum]] | * [[Vacuum]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

| Line 68: | Line 64: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

| − | * Cao, Tian Yu | + | * Cao, Tian Yu. ''Conceptual Foundations of Quantum Field Theory''. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004 (original 1999). ISBN 0521602726. |

| − | * Dittrich, Walter, and H. Gies | + | * Dittrich, Walter, and H. Gies. ''Probing the Quantum Vacuum: Perturbative Effective Action Approach''. Berlin, DE: Springer, 2000. ISBN 3540674284. |

| − | * Fain, Benjamin | + | * Fain, Benjamin. ''Irreversibilities in Quantum Mechanics: Fundamental Theories of Physics''. vol 113. New York, NY; London, UK: Springer/Kluwer Academic, 2000. ISBN 079236581X. |

| − | * Fulling, Stephen A | + | * Fulling, Stephen A. ''Aspects of Quantum Field Theory in Curved Space-time''. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0521377683. |

| − | * Genz, Henning | + | * Genz, Henning. ''Nothingness: The Science of Empty Space''. Basic Books, 2001. ISBN 0738206105. |

| − | * Gillespie, Charles Coulston ed. | + | * Gillespie, Charles Coulston (ed.). ''Dictionary of Scientific Biography.'' Detroit, MI: Macmillan USA, 2008 (original 1981). ISBN 978-0684169668 |

| − | * Jackson, John | + | * Jackson, John D. ''Classical Electrodynamics,'' 3rd ed. New York, NY: Wiley, 1998. ISBN 0471309321. |

| − | * Kane, Gordon | + | * Kane, Gordon. ''Supersymmetry: Squarks, Photinos, and the Unveiling of the Ultimate Laws''. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishers, 2000. ISBN 0738204895. |

| − | * Lambrecht, Astrid | + | * Lambrecht, Astrid. "Observing mechanical dissipation in the quantum vacuum: an experimental challenge." In Figger, Hartmut, Dieter Meschede, and Claus Zimmermann (eds.). ''Laser Physics at the Limits''. Berlin, DE: Springer, 2002. ISBN 3540424180. |

| − | * Ray, Christopher | + | * Ray, Christopher. ''Time, Space and Philosophy''. New York, NY: Routledge, 1991. ISBN 0415032210. |

| − | * Rozanov, L.M., and M.H. Hablanian | + | * Rozanov, L.M., and M.H. Hablanian. ''Vacuum Technique''. London, UK: Taylor & Francis, 2002. ISBN 0415273510. |

| − | * Saunders, S., and H.R. Brown eds | + | * Saunders, S., and H.R. Brown eds. ''The Philosophy of Vacuum''. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1991. ISBN 0198244495. |

| − | * Scully, Marian O., and M.S. Zubairy | + | * Scully, Marian O., and M.S. Zubairy. ''Quantum Optics''. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 0521435951. |

| − | * Woit, Peter | + | * Woit, Peter. ''Not Even Wrong: The Failure of String Theory and the Search for Unity in Physical Law''. New York, NY: Basic Books, 2006. ISBN 0465092756. |

| − | * Wynn-Williams, Gareth | + | * Wynn-Williams, Gareth. ''The Fullness of Space''. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 0521426383. |

| − | * Yokoyama, Hiroyuki., and K. Ujihara | + | * Yokoyama, Hiroyuki., and K. Ujihara. ''Spontaneous Emission and Laser Oscillation in Microcavities''. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 1995. ISBN 0849337860. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Physical sciences]] | [[Category:Physical sciences]] | ||

Latest revision as of 19:32, 8 October 2022

| Electromagnetism | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

Electricity ·Magnetism

| ||||||||||||

In classical physics, free space, sometimes called the vacuum of free space, refers to a region of space where there is a theoretically "perfect" vacuum. It is a concept of electromagnetic theory. This concept is an abstraction from nature, a baseline or reference state that is unattainable in practice, like the absolute zero of temperature. The definitions of the ampere and meter SI units are based on measurements corrected to refer to free space. In the theory of quantum mechanics, the "quantum vacuum" is not entirely empty but contains electromagnetic waves and particles that pop in and out of existence. The differences between free space and the quantum vacuum are predicted to be very small.

Properties of free space

Free space is characterized by the defined value of the parameter μ0 known as the permeability of free space or the magnetic constant,[1] and the defined value of the parameter ε0 called the permittivity of free space or the electric constant.[2]

Maxwell viewed permeability as being a quantity related to density, and he viewed dielectric constant, the reciprocal of permittivity, as being a quantity related to transverse elasticity. He used these quantities in Newton's equation for the speed of sound to obtain a wave speed equal to the speed of light c0. This famous calculation concludes around equation (136) in Part III of his 1861 paper "On Physical Lines of Force" with the estimate that c0=195,647 miles per second. The logical status of the electric and magnetic constant in SI units has shifted, however, and the velocity of light is now a defined value, not a measured or observed value. See the related articles on meter, ampere (unit) and speed of light.[3][4] The parameter ε0 also enters the expression for the fine-structure constant usually denoted by α,[5] which characterizes the strength of the electromagnetic interaction.

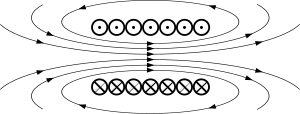

In the reference state of free space, according to Maxwell's equations, electromagnetic waves, such as radio waves and visible light (among other electromagnetic spectrum frequencies) propagate at the defined speed of light, c0.[6] According to the theory of special relativity, this speed is independent of the speed of the observer or of the source of the waves. The electric and magnetic fields in these waves are related by the defined value of the characteristic impedance of vacuum Z0.[7]

In addition, in this reference state, the principle of linear superposition of potentials and fields holds. For example, the electric potential generated by two charges is the simple addition of the potentials generated by each charge in isolation.[8]

What is the vacuum?

The ideal vacuum of free space is not the same as a physically obtainable vacuum. Physicists use the term "vacuum" in several ways. One use is to discuss ideal test results that would occur in a "perfect vacuum," which physicists simply call vacuum or free space in this context. Physicists use the term partial vacuum to refer to the imperfect vacuum realizable in practice. The term "partial vacuum" suggests a space where the pressure is low but not zero.

Quantum vacuum

Today, the classical concept of vacuum as a simple void has been replaced by the quantum vacuum, separating "free space" still further from the earlier concept of a perfect vacuum. Quantum vacuum or the vacuum state is not empty.[9] An approximate meaning is as follows:[10]

Quantum vacuum describes a region devoid of real particles in its lowest energy state.

Lambrecht[11] has noted that the quantum vacuum is "by no means a simple empty space," and Ray[12] has observed that "it is a mistake to think of any physical vacuum as some absolutely empty void."

According to quantum mechanics, empty space (the "vacuum") is not truly empty but instead contains fleeting electromagnetic waves and particles that pop in and out of existence.[13] One measurable result of these ephemeral occurrences is the Casimir effect.[14][15] Other examples are spontaneous emission[16][17][18] and the Lamb shift.[19] Related to these differences, quantum vacuum differs from free space in exhibiting nonlinearity in the presence of strong electric or magnetic fields (violation of linear superposition).

Even in classical physics, it was realized that the vacuum must have a field-dependent permittivity in the strong fields found near point charges.[20][21] These field-dependent properties of the quantum vacuum continue to be an active area of research.[22][23]

At present, even the meaning of the quantum vacuum state is not settled. For example, what constitutes a "particle" depends on the gravitational state of the observer.[24][25] Speculation abounds on the role of the quantum vacuum in an expanding universe. In addition, the quantum vacuum may exhibit spontaneous symmetry breaking.[26]

The discrepancies between free space and the quantum vacuum are predicted to be very small, and to date there is no suggestion that these uncertainties affect the use of SI units, the implementation of which is predicated on the undisputed predictions of quantum electrodynamics.[27]

In short, realization of the ideal of "free space" is not just a matter of achieving low pressure, as the term partial vacuum suggests. In fact, "free space" is an abstraction from nature, a baseline or reference state, that is unattainable in practice.[28]

Realization of free space in a laboratory

By "realization" is meant the reduction to practice, or experimental embodiment, of the term "free space," for example, a partial vacuum. What is the operational definition of free space? Although in principle free space is unattainable, like the absolute zero of temperature, the SI units are referred to free space, and so an estimate of the necessary correction to a real measurement is needed. An example might be a correction for non-zero pressure of a partial vacuum. Regarding measurements taken in a real environment (for example, partial vacuum) that are to be related to "free space," the CIPM cautions that:[29]

In all cases any necessary corrections be applied to take account of actual conditions such as diffraction, gravitation or imperfection in the vacuum.

In practice, a partial vacuum can be produced in the laboratory that is a very good realization of free space. Some of the issues involved in obtaining a high vacuum are described in the article on ultra high vacuum. The lowest measurable pressure today is about 10−11 Pa.[30] (The abbreviation Pa stands for the unit pascal, 1 pascal = 1 N/m2.)

Realization of free space in outer space

Although it is only a partial vacuum, outer space contains such sparse matter that the pressure of interstellar space is on the order of 10 pPa (1×10−11 Pa).[31] For comparison, the pressure at sea level (as defined in the unit of atmospheric pressure) is about 101 kPa (1×105 Pa). The gases in outer space are not uniformly distributed, of course. The density of hydrogen in our galaxy is estimated at 1 hydrogen atom/cm3.[32] In the partial vacuum of outer space, there are small quantities of matter (mostly hydrogen), cosmic dust and cosmic noise. See intergalactic space. In addition, there is a cosmic microwave background with a temperature of 2.725 K, which implies a photon density of about 400 /cm3.[33] (This background temperature depends upon the gravitational state of the observer. See Unruh effect.)

The density of the interplanetary medium and interstellar medium, though, is extremely low; for many applications negligible error is introduced by treating the interplanetary and interstellar regions as "free space."

U.S. Patent Office interpretation of free space

The United States Patent Office defines "free space" in a number of ways. For radio and radar applications the definition is "space where the movement of energy in any direction is substantially unimpeded, such as the atmosphere, the ocean, or the earth" (Glossary in US Patent Class 342, Class Notes).[34] This definition does not match the technical definitions of free space outlined above, which do not refer to a medium.

Another US Patent Office interpretation is Subclass 310: Communication over free space, where the definition is "a medium which is not a wire or a waveguide."[35] This definition bears little if any relation to other technical definitions of free space outlined above.

See also

- Electromagnetism

- Elementary particle

- Outer space

- Particle physics

- Speed of light

- SI units

- Vacuum

Notes

- ↑ NIST, magnetic constant. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ NIST, electric constant. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ J.C. Maxwell, On Physical Lines of Force, vacuum-physics.com. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ↑ Gillespie (2008), 14.

- ↑ NIST, fine structure constant α. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ NIST, speed of light in vacuum: c, c0. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ NIST, impedance of vacuum: Z0. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ Jackson (1999), 10, 13.

- ↑ Dittrich and Gies (2000).

- ↑ Kane (2000), Appendix A, 149 ff.

- ↑ Lambrecht (2002), 197.

- ↑ Ray (1991), 205.

- ↑ AIP, AIP Physics News Update. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ↑ APS, Physical Review Focus Dec, focus.aps.org. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ↑ F. Capasso, J.N. Munday, D. Iannuzzi, and H.B. Chen, 2007, Casimir forces and quantum electrodynamical torques: Physics and nanomechanics, Harvard University. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ↑ Yokoyama, and Ujihara (1995), 6.

- ↑ Fain (2000), §4.4; 113ff.

- ↑ Scully and Zubairy (1997), §1.5.2; 22–23

- ↑ Scully, and Zubairy (1997), 13-16.

- ↑ M. Born and L. Infeld, Proc. Royal Soc. London A144 (1934):425.

- ↑ Jackson (1999), 10–12.

- ↑ A. Di Piazza, K. Z. Hatsagortsyan, and C. H. Keitel, 2006, Light diffraction by a strong standing electromagnetic wave, Phys. Rev. Lett.; Gies, Holger, Joerg Jaeckel, and Andreas Ringwald, 2006, Polarized light propagating in a magnetic field as a probe for millicharged fermions, Phys. Rev. Letts. 97. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ↑ Saunders and Brown (1991) and Genz (2002).

- ↑ Fulling (1989), 259.

- ↑ Cao (1999), 179.

- ↑ Woit, 2006.

- ↑ Genz (2002), 247.

- ↑ Paulo N. Correa and Alexandra N. Correa, The Sagnac and Michelson-Gale-Pearson Experiments: The tribulations of general relativity with respect to rotation. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ↑ NIST, CIPM adopted Recommendation 1 (CI-1983). physics.nist.gov. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ↑ Rozanov and Hablanian (2002), 80.

- ↑ MiMi Zheng, Pressure in Outer Space, The Physics Factbook. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ↑ Wynn-Williams (1992), 38.

- ↑ Martin J. Rees, Origin of pregalactic microwave background, Nature 275: 35–37.

- ↑ USPTO, Classification Definitions, U.S. Patent Classification System, June 30, 2000. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ↑ USPTO, Subclass 310: Communication over free space. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cao, Tian Yu. Conceptual Foundations of Quantum Field Theory. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004 (original 1999). ISBN 0521602726.

- Dittrich, Walter, and H. Gies. Probing the Quantum Vacuum: Perturbative Effective Action Approach. Berlin, DE: Springer, 2000. ISBN 3540674284.

- Fain, Benjamin. Irreversibilities in Quantum Mechanics: Fundamental Theories of Physics. vol 113. New York, NY; London, UK: Springer/Kluwer Academic, 2000. ISBN 079236581X.

- Fulling, Stephen A. Aspects of Quantum Field Theory in Curved Space-time. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0521377683.

- Genz, Henning. Nothingness: The Science of Empty Space. Basic Books, 2001. ISBN 0738206105.

- Gillespie, Charles Coulston (ed.). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Detroit, MI: Macmillan USA, 2008 (original 1981). ISBN 978-0684169668

- Jackson, John D. Classical Electrodynamics, 3rd ed. New York, NY: Wiley, 1998. ISBN 0471309321.

- Kane, Gordon. Supersymmetry: Squarks, Photinos, and the Unveiling of the Ultimate Laws. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishers, 2000. ISBN 0738204895.

- Lambrecht, Astrid. "Observing mechanical dissipation in the quantum vacuum: an experimental challenge." In Figger, Hartmut, Dieter Meschede, and Claus Zimmermann (eds.). Laser Physics at the Limits. Berlin, DE: Springer, 2002. ISBN 3540424180.

- Ray, Christopher. Time, Space and Philosophy. New York, NY: Routledge, 1991. ISBN 0415032210.

- Rozanov, L.M., and M.H. Hablanian. Vacuum Technique. London, UK: Taylor & Francis, 2002. ISBN 0415273510.

- Saunders, S., and H.R. Brown eds. The Philosophy of Vacuum. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1991. ISBN 0198244495.

- Scully, Marian O., and M.S. Zubairy. Quantum Optics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 0521435951.

- Woit, Peter. Not Even Wrong: The Failure of String Theory and the Search for Unity in Physical Law. New York, NY: Basic Books, 2006. ISBN 0465092756.

- Wynn-Williams, Gareth. The Fullness of Space. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 0521426383.

- Yokoyama, Hiroyuki., and K. Ujihara. Spontaneous Emission and Laser Oscillation in Microcavities. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 1995. ISBN 0849337860.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.