Difference between revisions of "Evil" - New World Encyclopedia

({{Contracted}}) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (134 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{approved}}{{ebcompleted}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}}{{2Copyedited}} |

| − | + | [[File:Extermination of Evil Sendan Kendatsuba crop.jpg|thumb|400px|Sendan Kendatsuba, one of the eight guardians of [[Buddhist]] law, banishing evil in one of the five paintings of ''Extermination of Evil'']] | |

| − | + | '''Evil''' is a term used to describe something that brings about harmful, painful, and unpleasant effects. It is understood to be of three kinds: [[morality|Moral]] evil, [[nature|natural]] evil, and [[metaphysics|metaphysical]] evil. Moral evil is evil human beings volitionally and intentionally originate, and its examples are their cruel, vicious, and unjust thoughts and actions, such as [[murder]]. Natural evil is evil which occurs independently of human thoughts and actions, but which still causes pain and suffering, and it refers to [[earthquake]]s, [[volcano]]s, storms, droughts, [[disease]]-causing bacilli, and so on. "Metaphysical evil," a term coined by [[Gottfried Leibniz]] (1646-1716), refers to the finite and limited condition of the created spatio-temporal world, thus being usually understood not to be evil in and of itself. | |

| − | + | The [[monotheism|monotheistic]] [[religion]]s of [[Judaism]], [[Christianity]], and [[Islam]] usually have a criterion of good and a criterion of evil centering on a good [[God]] and tend to stress the seriousness of moral evil according to these standards, basically treating the other kinds of evil only in the context of moral evil. By contrast, most non-monotheistic religions (except dualistic religions and Confucianism) are inclined not to see a distinction amongst the three kinds of evil, saying that all evil is basically unreal in the end. Today, evil is much discussed in [[psychology]], [[sociology]], [[business]], and [[politics]], and evil in these areas refers to moral evil. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | There are several difficult issues on evil such as: The origin of evil, the virulence of evil, and the criterion of evil. A huge variety of ways to address these issues have been suggested by people from different walks of life. The recent trend seems to show, however, that new, insightful, and more acceptable ways of addressing the issues have emerged, helping to overcome the difficult and irrelevant aspects of the accepted traditions. For example, the origin of evil is increasingly translated into a new question of how to eradicate evil, and the so-called free-will defense is increasingly under review, so that free will may not necessarily contradict influences from outside agents; the virulence of evil is being more appreciated in disagreement with the traditional non-being theme of evil in Christianity; and the criterion of evil, in spite of much diversity of perspectives on it, can be a more universally accepted criterion, if it is simply understood in terms of selfishness vis-à-vis unselfishness. | ||

| − | == Etymology == | + | ==Etymology== |

| − | The [[ | + | The modern [[English]] word "evil" (Old English, ''yfel'') and its current living cognates, such as the German ''Übel,'' are widely considered to come from a Proto-Germanic reconstructed form ''*Ubilaz,'' comparable to the Hittite ''huwapp-,'' ultimately from the Proto-Indo-European form ''*wap-'' and suffixed zero-grade form ''*up-elo-''. Other later Germanic forms include Middle English ''evel,'' ''ifel,'' ''ufel,'' Old Frisian ''evel'' (adjective & noun), Old Saxon ''ubil,'' Old High German ''ubil,'' and Gothic ''ubils''. The root meaning is of obscure origin, though shown to be akin to modern English "over" (OE ''ofer'') and "up" (OE ''up,'' ''upp'') with the basic idea of "transgressing." |

| − | == | + | ==Kinds of evil== |

| − | + | There are three kinds of evil: Moral evil, natural evil, and metaphysical evil. Although this is primarily a Christian distinction, it can be used in reference to other religion's views of evil and more secular views of evil as well. | |

| − | + | Moral evil is volitionally committed by human being, as they are understood to have free will. It includes various forms of sin, such as war, murder, theft, and lying. Natural evil occurs basically independently of human thoughts and actions. Its examples are earthquakes, volcanoes, tornadoes, hurricanes, droughts, and diseases. Finally, metaphysical evil, although in and of itself it is not evil, can be treated as a kind of evil when it is defined as the finitude of the created word. The relevance of metaphysical evil can be understood better in the context of [[dharma|dharmic]] religions, such as [[Hinduism]] and [[Buddhism]], which do not hesitate to discuss it among other evils as something humans cannot avoid. | |

| − | + | [[Langdon Gilkey]] makes an entirely different distinction of evils in terms of magnitude: "Manageable" evil and "unmanageable" evil. Manageable evil is something humans can manage to have control over, while unmanageable evil is beyond humanity's control. The latter includes [[fate]], sin, and [[death]].<ref name=Gilkey>Langdon Gilkey, ''Maker of Heaven and Earth'' (University Press of America, 1985, ISBN 978-0819149763).</ref> | |

| − | + | ==World religions on evil== | |

| + | There is one thing in common among all [[religion]]s: They are all aware of the presence of evil, and none of them glorifies evil. But their understandings of evil are diverse. The [[monotheism|monotheistic]] religions of [[Judaism]], [[Christianity]], and [[Islam]] believe that [[God]], as a God of [[omnipotence]] and benevolence, has not created evil (perhaps with the exception of an angel called [[Satan]] in Judaism), that the presence of evil is due to the [[morality|moral]] downfall of human beings in connection with a temptation from a personal identity called Satan, and that God permits natural evil to be incurred either as a punishment for humanity's moral downfall or as a test for its growth. | ||

| − | + | [[Dualism|Dualistic]] religions, such as [[Zoroastrianism]] and [[Manichaeism]], attribute evil in the world to the God of evil as opposed to the God of good, but believe that the struggle between good and evil in the world will eventually come to an end. One difference between Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism is that the former talks about our moral evil as something still avoidable, while the latter does not on account of its fatalistic view of humans as a commingling of good [[soul]] and evil [[matter]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Dharmic religions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism in the East, teach that evil unavoidably manifests in the world because of [[karma]], but that evil is unreal in this unreal world of suffering, as long as people are to transcend it by overcoming their ignorance of the karma. When evil is unreal, if unavoidable, in this unreal world, no distinction has to be made between moral and natural evil. This notion of evil even seems to allude, also, to what is called [[metaphysics|metaphysical]] evil. [[Taoism]] in the Far East, in its view of evil as basically unreal, thus seems to resemble the dharmic religions. Another major religion of the Far East, [[Confucianism]], is quite different from other religions in the East, because it is more corporeal, focusing on moral evil as well as good in society. | |

| − | === | + | ===Monotheistic religions=== |

| − | In the [[Hebrew | + | *'''Judaism'''—In Judaism, evil is the result of dissociating from God's will expressed in his laws. Judaism stresses obedience to the God's laws as written in the [[Torah]] and the laws and rituals laid down in the [[Mishnah]] and the [[Talmud]]. In the [[Hebrew Bible]], evil is related to the concept of [[sin]], which means "to miss the mark" (''chata'' in Hebrew). The mark in question is the law of God. Human beings have God-given [[Free Will|free will]], the ability to choose between good and evil. They are expected not to choose evil, but God created an [[angel]] called Satan ''(haSatan)'', whose God-given mission is to tempt them to choose evil. (Satan himself has no free will, as he works as a servant of God.) Humans are given a great opportunity to exert their free will to overcome Satan and choose good, so that they may be able to inherit the good world in the end. God's purpose of creation is good, and his creation of Satan, after all, is to serve this good purpose by testing humans. According to Judaism, therefore, God created both good and evil for his good purpose: "See, I [God] have set before thee this day life and good, and death and evil" (Deuteronomy 30:15, KJV); and "I [God] form the light, and create darkness: I make peace, and create evil: I the Lord do all these things" ([[Book of Isaiah|Isaiah]] 45:7, KJV). Natural evils such as severe weather events and diseases are understood to be permitted by God to happen as punishment for the moral evil of disobeying God's will ([[Book of Deuteronomy|Deuteronomy]] 28:15-43; 31:17-18). |

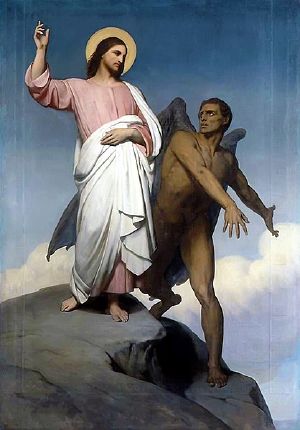

| + | [[File:Ary Scheffer - The Temptation of Christ (1854).jpg|thumb|300px|The [[devil]], in opposition to the will of God, represents evil and tempts [[Christ]] in ''The Temptation of Christ'' by Ary Scheffer]] | ||

| + | *'''Christianity'''—Christianity also teaches that evil results from disuniting with God's will. God's will is, of course, expressed in his laws of the [[Old Testament]] era; but, it is newly expressed in the teachings of [[Christ]], especially in his teaching of love, which is the whole of the law. But people commit moral evil (sin) by disobeying God's will. God, as an omnipotent and benevolent God, created humanity and the whole world as good creatures (Genesis 1:31), but humans, as well as angels, were given free will or free choice of the will ''(liberum arbitrium)''. Unlike Judaism, Christianity teaches that Satan was never created as a bad angel of temptation from the beginning but as a good angel with free will. That good angel among other angels, however, fell through free will in disobedience to God's will, thus becoming Satan. The [[fall]] of [[Adam and Eve]] centering on Satan consisted in their volitional disobedience to God's commandment not to eat of the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. The sin of Adam and Eve has been inherited to all their offspring as "original sin," which is so binding that humans are in depravity, having lost much of their ability to choose to follow God, and therefore, are in need of Christ's grace and forgiveness. According to [[Augustine]], natural evils take place as a rebellion of nature against humans because humans have rebelled against God. This Augustinian position is a standard view in Christianity on the relationship between moral and natural evil. But a question arises: Why is it that an omnipotent and good God did not prevent evil from occurring? A variety of answers have been given to this [[theodicy]] question. Augustine's free-will defense, developed during the time of his involvement with the Manichaean controversy, is based on his understanding that rational creatures are endowed with free will. But, another answer given by him argues in a largely [[Neo-Platonism|Neo-Platonic]] way, that evil is far from serious because it is simply "privation of good" ''(privatio boni)'', "non-substance" ''(non substantia)'', or "non-being" ''(non esse)''. It led him to say that evil, as understood this way, does not necessarily contradict the goodness and omnipotence of God. This position seems to have been favorably received in Christianity. | ||

| − | + | *'''Islam'''—According to Islam, evil arises when a person endowed with free will chooses to serve himself/herself instead of God. God is an almighty God of benevolence who teaches that people have to serve God as their supreme being and also love their fellow humans. These teachings are shown in the [[Qur'an]]. People commit sin when they, through the lure of Satan ''(Shaitan)'', selfishly choose to feel that they are important and not to take seriously the overwhelming importance of God. (Satan is not a fallen angel as is taught in Christianity, but a fallen member of the [[jinn]], a race of supernatural creatures. He, with his free will, refused to bow to Adam when God told him to do so.) People are to totally uphold God's teachings, even though God may let Satan tempt them or inflict evil and [[suffering]] on them as a test or, sometimes, as a punishment for their sins. Humanity's victory over all these difficulties in total obedience to God will eventually enable humans to enter into [[paradise]] where no evil exists, only the [[peace|peaceful]] satisfaction of the senses. Here, evil, whether moral or natural, as long as it is brought to people by God, seems to be a little more positively understood than in Judaism and Christianity, and the theodicy question can basically be answered by the rather positive role of evil enabling spiritual growth and development. | |

| − | + | ===Dualistic religions=== | |

| + | *'''Zoroastrianism'''—In the originally [[Persia|Persian]] religion of Zoroastrianism, the world is a battle ground between the God of good, [[Ahura Mazda]], and the God of evil, [[Angra Mainyu]] or Ahriman. All kinds of evil in the world are attributed to Angra Mainyu. Human beings, originally created by Ahura Mazda as allies in the struggle against Angra Mainyu, are free to choose between good and evil, but their acts, words, and thoughts will affect their lives after death. The final resolution of the struggle between good and evil is supposed to occur on a Day of [[Judgment]], in which a savior, ''Saoshyant,'' will come and the dead will rise for their final reward or punishment. Zoroatrianism is quasi-dualistic and not totally dualistic, since it talks about the ultimate victory of Ahura Mazda over Angra Mainyu. | ||

| − | + | *'''Manichaeism'''—Manichaeim, founded by [[Mani]] in the third century C.E., is an entirely dualistic religion that teaches the eternal conflict between the bright, spiritual realm of God and the dark, material realm of Satan. God in this context is a finite God. The creation of this world resulted from a commingling of the two opposing realms. Each human being is in the same way composed of two opposing things: Soul (good) and matter (evil). There is no moral evil in the sense of free will choosing evil. Therefore, there is no such thing as the Christian notion of the Fall. Evil is, rather, physical in the sense of the soul suffering from contact with matter. But in the last days, good and evil will return to their proper, separate realms, as they were in the beginning. | |

| − | + | ===Eastern religions=== | |

| + | *'''Hinduism'''—According to Hinduism, ''[[karma]]'' is the result of past actions (through many lifetimes); it, in turn, shapes one's desires. It is these desires that cause evil and bind humans to the world as they experience it. This world is not real. What is real is beyond desires and the confusions that exist as a consequence of such desires. The ''[dharma]]'' necessary to stop both desire and ignorance is described differently in the various branches of Hinduism. Common to many of these branches is the necessity to live one's state of life to the fullest. The consequence of this is many times described as one's place in the caste system. Three different paths are found to escape evil: The way of action ''(karma yoga)'', the way of devotion ''(bhakti yoga)'', and the way of knowledge ''(jnana yoga)''. Following these paths perfectly results in the destruction of individual evil and the individual as he/she now exists. | ||

| − | + | *'''Theravada Buddhism'''—The teaching of Siddhartha, the [[Buddha]], begins by facing those evils in life that cause suffering: Birth, decay, illness, death, the presence of who and what people hate, separation from who and what people love, the inability to obtain what people desire. These evils, and their consequent suffering, will only disappear when humans realize that they are unavoidable. There will always be those that suffer. To rid itself of all suffering and evil, humanity must rid itself of all desires—including the desire for existence. If people can rid themselves of all desires, they disappear into ''[[Nirvana]]''—beyond all being and non-being. The road to ''Nirvana'' is the [[eightfold path]]: Correct belief, aspirations, speech, conduct, means of livelihood, endeavor, mindfulness, and meditation. This Buddhist approach, perhaps as well as the Hindu approach, does not have to differentiate between moral and natural evil. | |

| − | + | *'''Taoism'''—Nothing in the world is essentially evil, since the world as the manifestation of the eternal ''Tao'' participates in the the ''Yin'' and ''Yang'' principles. Of course, ''Yin'' is a negative principle that could at least imply some kind of evil; but, it alone is not manifested, since it is manifested only with ''Yang,'' a positive principle. What is usually called evil may result from a lack of balance between ''Yin'' and ''Yang'' constituted by a bigger participation of the ''Yin'' principle. In this sense, evil belongs to the nature of the world, but it is still just a conceptual abstraction, having no permanent existence. Human beings, as part of the world, have to subscribe to the harmony of the two opposing principles. There seems to be no real distinction between moral and natural evil. | |

| − | + | *'''Confucianism'''—Confucianism teaches that individual humans each have free will by which they are to make good virtuous choices. Evils such as warring nations, non-loving families, envious business people, and destructive farming practices come from the lack of [[virtue]]s in individuals and a society that does not provide fertile ground for the growth of such virtues. Humans are their own living connections to other people and the entire universe. To live a virtuous life results in harmony and peace. To destroy or disfigure these relations introduces evil into societal living. There are, according to Confucianism, both inner and outer virtues that enable one to live a harmonious life. The primary inner virtue, for example, is ''[[jen]]'' (humaneness). Those who live this virtue continually think of the other person’s good rather than their own. An example of outer virtue is ''li'' which is acting properly in their relationships with each other: Parents and children; men and women; those in authority and those without such authority. Living a virtuous life results in a society without evil. Thus, the main focus of Confucianism is on moral good or evil. | |

| − | == | + | ==Moral evil in various areas of human life== |

| − | + | Many different experiences of [[morality|moral]] evil in human life have been pointed out by experts in [[psychiatry]], [[sociology]], [[business]], [[politics]], and so on. Already, moral evil has been dealt with primarily in [[monotheism|monotheistic]] religions. However, it would be of use to study those experiences of moral evil dealt with in the secular disciplines, which usually have no reference to a personal identity called [[Satan]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ===Evil from a psychiatric viewpoint=== |

| − | + | [[M. Scott Peck]] (1936-2005) discusses evil in his book, ''People of the Lie: The Hope for Healing Human Evil''.<ref>M. Scott Peck, '' People of the Lie: The Hope for Healing Human Evil'' (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983).</ref> Most of his conclusions about the psychiatric condition he designates, "evil," are derived from his close study of one patient he names Charlene. Although Charlene is not dangerous, she is ultimately unable to have empathy for others in any way. According to Peck, people like her see others as play things or tools to be manipulated for their uses or entertainment. He claims that these people are rarely seen by psychiatrists and have never been treated successfully. | |

| − | + | He gives some identifying characteristics for evil persons. | |

| + | An evil person: | ||

| − | + | * Projects his or her evils and sins onto others and tries to remove them from others | |

| + | * Maintains a high level of respectability and lies incessantly in order to do so | ||

| + | * Is consistent in his or her [[sin]]s. Evil persons are characterized not so much by the magnitude of their sins, but by their consistency | ||

| + | * Is unable to think from other people's viewpoints | ||

| − | + | Most evil people realize their evil deep within themselves but are unable to tolerate the pain of introspection or admit to themselves that they are evil. Thus, they constantly run away from their evil by putting themselves in a position of "moral superiority" and putting the focus of evil on others. Evil is an extreme form of character disorder. | |

| − | + | Scott Peck makes great efforts to keep much of his discussion on a [[science|scientific]] basis. He says that evil arises out of "free choice." He describes it thus: Every person stands at a crossroads, with one path leading to [[God]], and the other path leading to the devil. The path of God is the right path, and accepting this path is akin to submission to a higher power. However, if a person wants to convince himself and others that he has free choice, he would rather take a path which cannot be attributed to its being the ''right'' path. Thus, he chooses the path of evil. In this, it is close to the original Judeo-Christian concept of "sin" as a consistent process that leads to failure to reach one's true goals. | |

| − | + | ===Sociopaths=== | |

| + | A sociopath is a person with "antisocial" personality disorder, which is a bit more serious than M. Scott Peck's notion of evil above. The basic characteristic of a sociopath is a disregard for the rights of others. It is typified by extreme self-serving behavior and a lack of [[conscience]] as well as an inability to [[empathy|empathize]] with others and to restrain him or herself from, or to feel remorse for, harm personally caused to others. Very often the sociopath may look very charming, friendly, and considerate, but these attitudes turn out to be superficial and even deceptice. They are used as a way of pulling and blinding others to the personal sociopathic agenda behind the surface. Many sociopaths are engaged in alchohol or drug use as a way of heightening their antisocial personality. They want to heighten their antisocial personality because they usually have a low self-esteem, for which they try to compensate through the use of these substrances. | ||

| − | + | Some sociologists, psychiatrists and [[neuroscience|neuroscientists]] have attempted to construct scientific explanations for the development of antisocial personality disorder. Although any diagnosis of sociopathy is sometimes criticized as being, at the present time, no more scientific than calling a person "evil," nevertheless it seems that sociopathy has something to do with moral evil, as long is its basic characteristic is a disregard for the rights of other people. | |

| − | == | + | ===Evil in business=== |

| + | In business, evil refers to unfair business practices. The most widely agreed on unfair practices are sweatshops and [[monopoly|monopolies]], but recently the term "evil" has been applied much more broadly, especially in the [[technology]] and [[intellectual property]] industries. One of the slogans of [[Google]] is "Don't Be Evil," in response to much-criticized technology companies such as [[Microsoft]] and [[AOL]], and the tag line of independent music recording company Magnatune is "we are not evil," referring to the alleged evils of the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). The economist [[David Korten]] has argued that industrial [[corporations]], set up as fictive individuals by law, are required to work only according to the criteria of making [[profit]]s for their shareholders, meaning they function as sociopathic organizations that inherently do evil in damaging the [[environmentalism|environment]], denying labor justice, and exploiting the powerless. | ||

| − | + | ===Evil in a political context=== | |

| + | In liberal-democratic societies, many associate evil in politics as revolving around authoritarian and, especially, [[totalitarianism|totalitarian]] regimes, as well as demagogue leaders, such as the [[Nazi]] regime of [[Adolf Hitler]] in [[Germany]] for its mass genocide of Jews in the [[Holocaust]], war crimes, as well as political and cultural persecution. In [[World War II]] and the post war years to present, liberal-democratic societies view Hitler as a symbol of political and social evil in the modern world and is portrayed as such in most media presentations and representations of him. The [[Communism|Communist]] regime of the [[Soviet Union]] has also been considered to be evil by a number of western liberal democracies, especially under the rule of [[Joseph Stalin]], for its mass persecutions of political opponents, religious, and cultural minorities (for example, the Cossacks). | ||

| − | + | The political writings of [[Niccolò Machiavelli]] (1469-1527) in ''The Prince,'' often used by [[Hitler]] and [[Mussolini]], are considered to be a source of evil in politics, as they often speak of ignoring accepted morals for the pursuit of ultimate power, as "the ends justifies the means." Machiavelli favored a prince creating a climate of fear in order to rule a population, rather than relying on popular support. Machiavelli supports the use of deception and manipulation as means to increase a prince's personal power. All these show little concern for traditional moral and ethical considerations in the thinking of Machiavelli. Thus, when the term "Machiavellian" is used to describe politicians or political policy, it is often being used in a negative context, referring to Machiavelli's support of deception and manipulation to attain and preserve power. | |

| − | + | On the other hand, authoritarian, totalitarian, and elements of religious [[fundamentalism|fundamentalist]] regimes tend to hold a common view that liberal-democratic regimes are evil and blame liberal democracy for high crime rates, profiteering, corporate crime, [[materialism|materialist]] [[individualism]] replacing common bonds of similar people, destruction of culture and its replacement with sleaze. All of which, the regimes claim, will result in the destruction of humanity if liberal democracy is not restrained. | |

| − | + | ===Systemic evil=== | |

| − | + | These days, the term "systemic evil" is heard quite often. It refers to moral evil committed by an organization or a social institution or system. Traditionally, moral evil has been regarded mainly as something committed by an individual person, but systemic evil is a social sin coming from a system collectively. An organization or a social institution or system usually has its own culture, and its members tend to be, [[psychology|psychologically]], very easily influenced by it. If the culture is dominated by any unhealthy ideologies or thoughts, such as [[totalitarianism]], [[authoritarianism]], [[institutionalism]], mammonism, [[racism]], and [[sexism]], then the organization or social institution as a whole is found to be collectively committing systemic evil, and its members are consciously or unconsciously participating in the evil. Imperialism, [[Communism]], [[Nazism]], sociopathic industrial corporations, inflexible church institutions, and the [[Ku Klux Klan]] are some of its examples. This evil was already pointed out by [[Walter Rauschenbusch]] early in the twentieth century, who said that it exerts the "super-personal forces of evil."<ref>Walter Rauschenbusch, ''A Theology of the Social Gospel'' (Andesite Press, 2015, ISBN 978-1297625961).</ref> Although this evil was touched upon to some degree in the above discussion of evil in business and politics, it deserves a separate discussion here because its fearsome implications are taken seriously by many people today. It is more and more understood that sin is not only personal, but also social and collective. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Some issues on evil== | |

| + | ===The origin of evil=== | ||

| + | Those who believe, as in [[monotheism|monotheistic]] [[religion]]s, that [[God]] is [[omnipotence|omnipotent]] and good, usually ask why, then, evil was originated in the world. Couldn't such a God have prevented evil from occurring? This is what is called the [[theodicy]] question, and it asks how to solve the problem of the contradiction of the three statements: 1) That God is omnipotent; 2) that God is good; and 3) that evil actually exists. Traditionally, there are three logical ways to address the problem. A first way is to qualify or deny the omnipotence of God, that is, to regard God as a finite God. Various forms of [[dualism]], such as [[Zoroastrianism]] and [[Manichaeism]], are its examples, and even some [[Christianity|Christians]] such as [[Edwin Lewis]] have taken this dualistic position.<ref>Edwin Lewis, ''The Creator and the Adversary'' (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1948).</ref> A second way is to qualify or negate the total goodness of God, that is, to say that God must be evil as well as good. This position has been taken by Christians like [[Frederick Sontag]].<ref>Frederick Sontag, ''God, Why Did You Do That'' (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1970).</ref> A third logical way is to qualify the existence of evil, by saying that evil is just non-being or privation of good. Many famous theologians such as [[Augustine]] and [[Thomas Aquinas]] adhere to this position, which has been quite widespread in Christianity. But, these three traditional ways have been criticized of being just logical answers incapable of actually eradicating evil in the world. Evil is still there. | ||

| − | [[ | + | These days, therefore, a possibly better approach is increasingly appreciated, and it is the free-will defense in its various forms. This defense, anyway, has already been largely adopted by the monotheistic religions of [[Judaism]], Christianity, and [[Islam]], because, as was seen above, they teach that humans chose evil through their God-given [[Free Will|free will]]. It attempts to defend God's omnipotence and goodness, placing the possibility of evil only in human free will, which can choose good or evil. It usually argues also that, so far, there has been no free will which always chooses good. Alvin Plantinga has philosophically articulated this defense in his ''God, Freedom, and Evil''.<ref>Alvin Plantigna, ''God, Freedom, and Evil'' (Eerdmans, 1989, ISBN 978-0802817310).</ref> And, to this free-will defense a new flavor has been added by people such as Kenneth Surin in their assertion that, instead of just intellectually discussing about the origination of evil from free will, people should make positive use of their free will to "practically" help to get rid of evil, by committing themselves to, being present with, and showing the suffering love of God to, the victim of evil.<ref>Kenneth Surin, ''Theology and the Problem of Evil'' (Oxford: Basic Blackwell, 1986).</ref> This trend is called "practical" theodicy. |

| − | According to | + | The free-will defense, however, seems to have at least one weakness: It places the possibility of evil only in free will, neglecting any influence of temptation from outside. According to Augustine, free will's moral choice of evil has no [[efficient cause]] whatsoever and its cause is "deficient" in that it simply comes from the finitude of free will: "Let no one, therefore, look for an efficient cause of the evil will; for it is not efficient, but deficient, as the will itself is not an effecting of something, but a defect."<ref>''The City of God'' XII.7, tr. Marcus Dods (New York: Modern Library, 2000), 387.</ref> Interestingly, here lies some relevance of metaphysical evil, which itself is not evil, to the origin of evil. But, the weakness of the free-defense is evident from the widely known biblical account of how Eve was tempted by the serpent (a fallen angel) to sin and how Adam was then tempted by Eve to sin (Genesis 1:1-13). If the Bible is correct on the involvement of temptation, and if it is also correct that [[Adam and Eve]] were endowed with free will, a reasonable alternative interpretation would be that they fell because some strong power of temptation prevented them from fully exerting their God-given free will for God's purpose. Perhaps, that "strong power of temptation," even stronger than free will, can only come from love, which can eventually drive rational creatures toward a sexual relationship even if it may be entirely opposite to God's purpose. In a nutshell, it is very possible that the human fall in the Garden of Eden took place because free will was not fully used to align love with God's purpose. Perhaps that is the reason why some early Christian Church Fathers, such as [[Clement of Alexandria|St. Clement of Alexandria]] and [[Ambrose|St. Ambrose]], actually believed that the fall of Adam and Eve was a sexual sin.<ref>Ludwig Ott, ''Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma,'' ed. James Canon Bastible, tr. Patrick Lynch (Rockford, IL: Tan Books and Publishers, 1960), 107.</ref> Even in this case, God can still be defended because it can be understood, as many people agree, that God gave humans free will out of his love for them, so that they as his children might successfully use it to become his partners of love. |

| − | + | For the Eastern religions (perhaps except for [[Confucianism]]), the above theodicy question does not arise at least for two reasons: 1) Because they do not believe in an monotheistic God of omnipotence and love; and 2) because they treat evil in the world as unreal. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===The virulence of evil=== | |

| + | Only [[dualism|dualistic]] religions seem to take evil very seriously; they explain the virulent reality of evil, by attributing it to the God of evil who existed along with the God of good from eternity. Many of the Eastern religions accept evil as an unavoidable consequence of the [[karma]]; but, they paradoxically end up treating it as unreal, by accepting evil through one's self-negation. Monotheistic religions refer to a personal identity called [[Satan]] as an agent of temptation, but they do not take evil as seriously as dualistic religions do. | ||

| − | + | Christian [[theology]], for example, has a widely accepted doctrine of evil as non-being, privation of good, absence of good, or diminution of good, thus treating evil as something non-substantial which one does not have to take very seriously. This doctrine was formulated by Augustine, who adopted the [[Neo-Platonism|Neo-Platonic]] tenet that all being is good, while only non-being is evil. Augustine treated even moral evil (sin) the same way. According to him, moral evil is simply a diminution of the moral rectitude of free will; so, it is again non-substantial. Furthermore, sin occurs under no influence upon free will. It only occurs through free will's own turning away from good. It only comes from one's free will and not from any temptation from outside. Sin has no efficient cause, as was mentioned above. (This may not sound Augustinian, because Augustine is usually known as a theologian of sin. But note that there was a considerable evolution and shift within his theology as the object of his attention was shifting from Manichaean heresy to [[Pelagius|Pelagian]] heresy.) | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | Besides this widely accepted Christian treatment of evil as non-being, there are some who developed ways on their own not to take evil seriously. According to [[Mary Baker Eddy]] (1821-1910), founder of [[Christian Science]], evil is [[ontology|ontologically]] unreal in the world created by God who is absolutely good and perfect. [[Spinoza]] (1632-1677), a Jewish philosopher of pantheism, argued that the whole world is divine, having no room for evil. | |

| − | + | But, if evil is simply ontologically unreal non-being, privation of good, or absence of good, how can people explain the [[demon|demonic]] character of many evils that happen in the world? How can one say that [[Hitler]]'s sin of killing six million Jews was ontologically unreal? Didn't it truly cause substantial pain and suffering to them and also to others who survived the [[Holocaust]]? Today, many people naturally ask this question. [[Carl Jung]] (1875-1961), a famous [[Switzerland|Swiss]] psychiatrist, decided that the traditional Christian view of evil as a ''privatio boni'' is a "morally dangerous" doctrine that "belittles" evil.<ref>"Two Letters to Father Victor White" from ''Jung on Evil,'' ed. Murray Stein (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996), 73.</ref> He felt that evil is as real as good. | |

| − | + | Many Muslims and fundamentalist and evangelical Christians, even though they are not dualists, tend to see Satan behind any sinful act, and this would support Jung's observation of the virulence of evil. But, if the sexual interpretation of the human fall by Clement of Alexandria and Ambrose is correct, then it can probably explain the demonic nature of evil even better. For the sexual interpretation makes it reasonable to think that the sinful relationship of sexual love of Adam, Eve, and the fallen angel (Satan) bound all human beings as "brood of vipers" (Matther 3:7) under the reign of Satan. If so, all sins can be understood to take place under the strong influence, and in the real presence, of Satan. This must be why the Bible says that Satan entered [[Judas Iscariot]] when he was betraying Jesus (Luke 22:3). | |

| − | + | ===The criterion of evil=== | |

| + | What is the criterion by which to determine what is evil? The question, in other words, is whether there is a universal, [[transcendent]] definition of evil, or whether evil is determined by one's social or cultural background. [[C.S. Lewis]], in ''The Abolition of Man,'' maintained that there are certain acts that are universally considered evil, such as [[rape]] and [[murder]].<ref>C.S. Lewis, ''The Abolition of Man'' (HarperOne, 2015, ISBN 978-0060652944).</ref> On the other hand, it is hard to find any act that was not acceptable in some society. The [[Ancient Greek|Greeks]] held favorable views regarding [[homosexuality|homosexual]] relationships between male youths and adult men. Less than 150 years ago, the [[United States of America]], [[Great Britain]], and many other countries practiced slavery of the [[Africa|African]] race that lasted for over 400 years. Even the [[Nazism|Nazis]], during [[World War II]], found [[genocide]] acceptable for their purpose, as did the Imperial Japanese Army with the [[Nanking Massacre]]. Today, there is strong disagreement as to whether homosexuality and [[abortion]] are perfectly acceptable or evils. | ||

| − | + | For monotheistic religions, the criterion of good is the will of God. For them, therefore, evil is disunity with, or disobedience to, the will of God. But, not all humans are monotheistic. Many belong to other religions, and still many are even unbelievers. Furthermore, the three monotheistic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam have different interpretations of the will of God. Even people of the same faith many times have different understanding of the same God. Thus, the reality is too much diversity. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | An additional problem is the fact that many people believe that some evil is good as long as it serves a good purpose. In fact, many religious people believe that human experiences of evil, whether it is given as a punishment or a test, can help people to grow to become more mature in front of God. Of course, if the evil people experience is too severe or "unmanageable,"<ref name=Gilkey/> then they can be crushed; and also if any evil is justified as a means to accomplish some end, it will create a problem. But, the instrumental role of evil for a noble purpose seems to be recognized at least to some degree everywhere. | |

| − | + | Given all this, what is the criterion of evil? One appropriate, perhaps more general and universal, way to put it would be to say that the selfishness is evil, while unselfishness is good. But, if it is still difficult to make an immediate judgment, one can wait until anything bears its fruit, which can speak as to whether it is evil or good: "By their fruit you will recognize them" (Matthew 7:16, NIV). | |

| − | == | + | ==Notes== |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * | + | *Augustine. ''The City of God''. Translated by Marcus Dods. New York: Modern Library, 2000. ISBN 0679783190. |

| − | * | + | *Cenkner, William. ''Evil and the Response of World Religion''. Paragon House, 1997. ISBN 1557787530. |

| + | *Ferré, Nels F. S. ''Evil and the Christian Faith''. Books for Libraries Press, 1971 (original 1947). ISBN 0836923936. | ||

| + | *Gadamer, Hans-Georg. ''Truth and Method''. 2nd, revised ed. Translated by Joel Weinsheimer and Donald G. Marshall. New York: Crossroad, 1991 (original 1982). ISBN 0824504313. | ||

| + | *Gilkey, Langdon. ''Maker of Heaven and Earth''. University Press of America, 1985. ISBN 978-0819149763 | ||

| + | *Kelly, Joseph F. ''The Problem of Evil in the Western Tradition: From the Book of Job to Modern Genetics''. Liturgical Press, 2002. ISBN 0814651046. | ||

| + | *Kushner, Harold S. ''When Bad Things Happen to Good People''. London: Pan, 2000 (original 1982). ISBN 0330268279. | ||

| + | *Lewis, C. S. ''The Abolition of Man''. HarperOne, 2015. ISBN 978-0060652944 | ||

| + | *Lewis, Edwin. ''The Creator and the Adversary''. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1948. | ||

| + | *McCloskey, H. J. ''God and Evil''. The Hague: Nijhoff, 1974. ISBN 9024716047. | ||

| + | *Nelson, Marie Coleman, and Michael Eigen. ''Evil: Self and Culture''. Human Sciences Press, 1984. ISBN 0898851432. | ||

| + | *Oppenheimer, Paul. ''Evil and the Demonic: A New Theory of Monstrous Behavior''. New York University Press, 1996. ISBN 0814761933. | ||

| + | *Ott, Ludwig. ''Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma''. Edited in English by James Canon Bastible. Translated by Patrick Lynch. Rockford, IL: Tan Books and Publishers, 1960. | ||

| + | *Peck, M. Scott. ''People of the Lie: The Hope for Healing Human Evil''. Simon and Schuster, 1983. ISBN 0671454920. | ||

| + | *Peterson, Michael L. ''God and Evil: An Introduction to the Issues''. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1998. ISBN 0813328497. | ||

| + | *Plantinga, Alvin. ''God, Freedom, and Evil.'' Eerdmans, 1989. ISBN 978-0802817310 | ||

| + | *Rauschenbusch, Walter. ''A Theology of the Social Gospel''. Andesite Press, 2015. ISBN 978-1297625961 | ||

| + | *Rosenberg, Marshall B. ''Speak Peace in a World of Conflict: What You Say Next Will Change Your World.'' PuddleDancer Press, 2005. ISBN 1892005174. | ||

| + | *Rosenberg, Shalom. ''Good and Evil in Jewish Thought''. Tel Aviv: MOD Books, 1996 (original 1989). ISBN 9650504486. | ||

| + | *Shermer, M. ''The Science of Good & Evil.'' New York: Time Books, 2004. ISBN 0805075208. | ||

| + | *Sontag, Frederick. ''God, Why Did You Do That?'' Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1970. ISBN 0664248861. | ||

| + | *Stein, Murray (ed.). ''Jung on Evil''. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996. ISBN 0691026176. | ||

| + | *Surin, Kenneth. ''Theology and the Problem of Evil''. Oxford: Basic Blackwell, 1986. ISBN 0631146644. | ||

| + | *Wolman, Benjamin B. ''The Psychoanalytic Interpretation of History''. Basic Books, 1971. ISBN 0465065937. | ||

| − | == | + | ==External Links== |

| − | + | All links retrieved March 23, 2024. | |

| − | + | *[https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05649a.htm Evil] ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. | |

| − | * [ | ||

| Line 139: | Line 150: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{credits|Evil|141682992|M._Scott_Peck|138033781}} |

Latest revision as of 23:52, 24 March 2024

Evil is a term used to describe something that brings about harmful, painful, and unpleasant effects. It is understood to be of three kinds: Moral evil, natural evil, and metaphysical evil. Moral evil is evil human beings volitionally and intentionally originate, and its examples are their cruel, vicious, and unjust thoughts and actions, such as murder. Natural evil is evil which occurs independently of human thoughts and actions, but which still causes pain and suffering, and it refers to earthquakes, volcanos, storms, droughts, disease-causing bacilli, and so on. "Metaphysical evil," a term coined by Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716), refers to the finite and limited condition of the created spatio-temporal world, thus being usually understood not to be evil in and of itself.

The monotheistic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam usually have a criterion of good and a criterion of evil centering on a good God and tend to stress the seriousness of moral evil according to these standards, basically treating the other kinds of evil only in the context of moral evil. By contrast, most non-monotheistic religions (except dualistic religions and Confucianism) are inclined not to see a distinction amongst the three kinds of evil, saying that all evil is basically unreal in the end. Today, evil is much discussed in psychology, sociology, business, and politics, and evil in these areas refers to moral evil.

There are several difficult issues on evil such as: The origin of evil, the virulence of evil, and the criterion of evil. A huge variety of ways to address these issues have been suggested by people from different walks of life. The recent trend seems to show, however, that new, insightful, and more acceptable ways of addressing the issues have emerged, helping to overcome the difficult and irrelevant aspects of the accepted traditions. For example, the origin of evil is increasingly translated into a new question of how to eradicate evil, and the so-called free-will defense is increasingly under review, so that free will may not necessarily contradict influences from outside agents; the virulence of evil is being more appreciated in disagreement with the traditional non-being theme of evil in Christianity; and the criterion of evil, in spite of much diversity of perspectives on it, can be a more universally accepted criterion, if it is simply understood in terms of selfishness vis-à-vis unselfishness.

Etymology

The modern English word "evil" (Old English, yfel) and its current living cognates, such as the German Übel, are widely considered to come from a Proto-Germanic reconstructed form *Ubilaz, comparable to the Hittite huwapp-, ultimately from the Proto-Indo-European form *wap- and suffixed zero-grade form *up-elo-. Other later Germanic forms include Middle English evel, ifel, ufel, Old Frisian evel (adjective & noun), Old Saxon ubil, Old High German ubil, and Gothic ubils. The root meaning is of obscure origin, though shown to be akin to modern English "over" (OE ofer) and "up" (OE up, upp) with the basic idea of "transgressing."

Kinds of evil

There are three kinds of evil: Moral evil, natural evil, and metaphysical evil. Although this is primarily a Christian distinction, it can be used in reference to other religion's views of evil and more secular views of evil as well.

Moral evil is volitionally committed by human being, as they are understood to have free will. It includes various forms of sin, such as war, murder, theft, and lying. Natural evil occurs basically independently of human thoughts and actions. Its examples are earthquakes, volcanoes, tornadoes, hurricanes, droughts, and diseases. Finally, metaphysical evil, although in and of itself it is not evil, can be treated as a kind of evil when it is defined as the finitude of the created word. The relevance of metaphysical evil can be understood better in the context of dharmic religions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism, which do not hesitate to discuss it among other evils as something humans cannot avoid.

Langdon Gilkey makes an entirely different distinction of evils in terms of magnitude: "Manageable" evil and "unmanageable" evil. Manageable evil is something humans can manage to have control over, while unmanageable evil is beyond humanity's control. The latter includes fate, sin, and death.[1]

World religions on evil

There is one thing in common among all religions: They are all aware of the presence of evil, and none of them glorifies evil. But their understandings of evil are diverse. The monotheistic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam believe that God, as a God of omnipotence and benevolence, has not created evil (perhaps with the exception of an angel called Satan in Judaism), that the presence of evil is due to the moral downfall of human beings in connection with a temptation from a personal identity called Satan, and that God permits natural evil to be incurred either as a punishment for humanity's moral downfall or as a test for its growth.

Dualistic religions, such as Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism, attribute evil in the world to the God of evil as opposed to the God of good, but believe that the struggle between good and evil in the world will eventually come to an end. One difference between Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism is that the former talks about our moral evil as something still avoidable, while the latter does not on account of its fatalistic view of humans as a commingling of good soul and evil matter.

Dharmic religions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism in the East, teach that evil unavoidably manifests in the world because of karma, but that evil is unreal in this unreal world of suffering, as long as people are to transcend it by overcoming their ignorance of the karma. When evil is unreal, if unavoidable, in this unreal world, no distinction has to be made between moral and natural evil. This notion of evil even seems to allude, also, to what is called metaphysical evil. Taoism in the Far East, in its view of evil as basically unreal, thus seems to resemble the dharmic religions. Another major religion of the Far East, Confucianism, is quite different from other religions in the East, because it is more corporeal, focusing on moral evil as well as good in society.

Monotheistic religions

- Judaism—In Judaism, evil is the result of dissociating from God's will expressed in his laws. Judaism stresses obedience to the God's laws as written in the Torah and the laws and rituals laid down in the Mishnah and the Talmud. In the Hebrew Bible, evil is related to the concept of sin, which means "to miss the mark" (chata in Hebrew). The mark in question is the law of God. Human beings have God-given free will, the ability to choose between good and evil. They are expected not to choose evil, but God created an angel called Satan (haSatan), whose God-given mission is to tempt them to choose evil. (Satan himself has no free will, as he works as a servant of God.) Humans are given a great opportunity to exert their free will to overcome Satan and choose good, so that they may be able to inherit the good world in the end. God's purpose of creation is good, and his creation of Satan, after all, is to serve this good purpose by testing humans. According to Judaism, therefore, God created both good and evil for his good purpose: "See, I [God] have set before thee this day life and good, and death and evil" (Deuteronomy 30:15, KJV); and "I [God] form the light, and create darkness: I make peace, and create evil: I the Lord do all these things" (Isaiah 45:7, KJV). Natural evils such as severe weather events and diseases are understood to be permitted by God to happen as punishment for the moral evil of disobeying God's will (Deuteronomy 28:15-43; 31:17-18).

- Christianity—Christianity also teaches that evil results from disuniting with God's will. God's will is, of course, expressed in his laws of the Old Testament era; but, it is newly expressed in the teachings of Christ, especially in his teaching of love, which is the whole of the law. But people commit moral evil (sin) by disobeying God's will. God, as an omnipotent and benevolent God, created humanity and the whole world as good creatures (Genesis 1:31), but humans, as well as angels, were given free will or free choice of the will (liberum arbitrium). Unlike Judaism, Christianity teaches that Satan was never created as a bad angel of temptation from the beginning but as a good angel with free will. That good angel among other angels, however, fell through free will in disobedience to God's will, thus becoming Satan. The fall of Adam and Eve centering on Satan consisted in their volitional disobedience to God's commandment not to eat of the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. The sin of Adam and Eve has been inherited to all their offspring as "original sin," which is so binding that humans are in depravity, having lost much of their ability to choose to follow God, and therefore, are in need of Christ's grace and forgiveness. According to Augustine, natural evils take place as a rebellion of nature against humans because humans have rebelled against God. This Augustinian position is a standard view in Christianity on the relationship between moral and natural evil. But a question arises: Why is it that an omnipotent and good God did not prevent evil from occurring? A variety of answers have been given to this theodicy question. Augustine's free-will defense, developed during the time of his involvement with the Manichaean controversy, is based on his understanding that rational creatures are endowed with free will. But, another answer given by him argues in a largely Neo-Platonic way, that evil is far from serious because it is simply "privation of good" (privatio boni), "non-substance" (non substantia), or "non-being" (non esse). It led him to say that evil, as understood this way, does not necessarily contradict the goodness and omnipotence of God. This position seems to have been favorably received in Christianity.

- Islam—According to Islam, evil arises when a person endowed with free will chooses to serve himself/herself instead of God. God is an almighty God of benevolence who teaches that people have to serve God as their supreme being and also love their fellow humans. These teachings are shown in the Qur'an. People commit sin when they, through the lure of Satan (Shaitan), selfishly choose to feel that they are important and not to take seriously the overwhelming importance of God. (Satan is not a fallen angel as is taught in Christianity, but a fallen member of the jinn, a race of supernatural creatures. He, with his free will, refused to bow to Adam when God told him to do so.) People are to totally uphold God's teachings, even though God may let Satan tempt them or inflict evil and suffering on them as a test or, sometimes, as a punishment for their sins. Humanity's victory over all these difficulties in total obedience to God will eventually enable humans to enter into paradise where no evil exists, only the peaceful satisfaction of the senses. Here, evil, whether moral or natural, as long as it is brought to people by God, seems to be a little more positively understood than in Judaism and Christianity, and the theodicy question can basically be answered by the rather positive role of evil enabling spiritual growth and development.

Dualistic religions

- Zoroastrianism—In the originally Persian religion of Zoroastrianism, the world is a battle ground between the God of good, Ahura Mazda, and the God of evil, Angra Mainyu or Ahriman. All kinds of evil in the world are attributed to Angra Mainyu. Human beings, originally created by Ahura Mazda as allies in the struggle against Angra Mainyu, are free to choose between good and evil, but their acts, words, and thoughts will affect their lives after death. The final resolution of the struggle between good and evil is supposed to occur on a Day of Judgment, in which a savior, Saoshyant, will come and the dead will rise for their final reward or punishment. Zoroatrianism is quasi-dualistic and not totally dualistic, since it talks about the ultimate victory of Ahura Mazda over Angra Mainyu.

- Manichaeism—Manichaeim, founded by Mani in the third century C.E., is an entirely dualistic religion that teaches the eternal conflict between the bright, spiritual realm of God and the dark, material realm of Satan. God in this context is a finite God. The creation of this world resulted from a commingling of the two opposing realms. Each human being is in the same way composed of two opposing things: Soul (good) and matter (evil). There is no moral evil in the sense of free will choosing evil. Therefore, there is no such thing as the Christian notion of the Fall. Evil is, rather, physical in the sense of the soul suffering from contact with matter. But in the last days, good and evil will return to their proper, separate realms, as they were in the beginning.

Eastern religions

- Hinduism—According to Hinduism, karma is the result of past actions (through many lifetimes); it, in turn, shapes one's desires. It is these desires that cause evil and bind humans to the world as they experience it. This world is not real. What is real is beyond desires and the confusions that exist as a consequence of such desires. The [dharma]] necessary to stop both desire and ignorance is described differently in the various branches of Hinduism. Common to many of these branches is the necessity to live one's state of life to the fullest. The consequence of this is many times described as one's place in the caste system. Three different paths are found to escape evil: The way of action (karma yoga), the way of devotion (bhakti yoga), and the way of knowledge (jnana yoga). Following these paths perfectly results in the destruction of individual evil and the individual as he/she now exists.

- Theravada Buddhism—The teaching of Siddhartha, the Buddha, begins by facing those evils in life that cause suffering: Birth, decay, illness, death, the presence of who and what people hate, separation from who and what people love, the inability to obtain what people desire. These evils, and their consequent suffering, will only disappear when humans realize that they are unavoidable. There will always be those that suffer. To rid itself of all suffering and evil, humanity must rid itself of all desires—including the desire for existence. If people can rid themselves of all desires, they disappear into Nirvana—beyond all being and non-being. The road to Nirvana is the eightfold path: Correct belief, aspirations, speech, conduct, means of livelihood, endeavor, mindfulness, and meditation. This Buddhist approach, perhaps as well as the Hindu approach, does not have to differentiate between moral and natural evil.

- Taoism—Nothing in the world is essentially evil, since the world as the manifestation of the eternal Tao participates in the the Yin and Yang principles. Of course, Yin is a negative principle that could at least imply some kind of evil; but, it alone is not manifested, since it is manifested only with Yang, a positive principle. What is usually called evil may result from a lack of balance between Yin and Yang constituted by a bigger participation of the Yin principle. In this sense, evil belongs to the nature of the world, but it is still just a conceptual abstraction, having no permanent existence. Human beings, as part of the world, have to subscribe to the harmony of the two opposing principles. There seems to be no real distinction between moral and natural evil.

- Confucianism—Confucianism teaches that individual humans each have free will by which they are to make good virtuous choices. Evils such as warring nations, non-loving families, envious business people, and destructive farming practices come from the lack of virtues in individuals and a society that does not provide fertile ground for the growth of such virtues. Humans are their own living connections to other people and the entire universe. To live a virtuous life results in harmony and peace. To destroy or disfigure these relations introduces evil into societal living. There are, according to Confucianism, both inner and outer virtues that enable one to live a harmonious life. The primary inner virtue, for example, is jen (humaneness). Those who live this virtue continually think of the other person’s good rather than their own. An example of outer virtue is li which is acting properly in their relationships with each other: Parents and children; men and women; those in authority and those without such authority. Living a virtuous life results in a society without evil. Thus, the main focus of Confucianism is on moral good or evil.

Moral evil in various areas of human life

Many different experiences of moral evil in human life have been pointed out by experts in psychiatry, sociology, business, politics, and so on. Already, moral evil has been dealt with primarily in monotheistic religions. However, it would be of use to study those experiences of moral evil dealt with in the secular disciplines, which usually have no reference to a personal identity called Satan.

Evil from a psychiatric viewpoint

M. Scott Peck (1936-2005) discusses evil in his book, People of the Lie: The Hope for Healing Human Evil.[2] Most of his conclusions about the psychiatric condition he designates, "evil," are derived from his close study of one patient he names Charlene. Although Charlene is not dangerous, she is ultimately unable to have empathy for others in any way. According to Peck, people like her see others as play things or tools to be manipulated for their uses or entertainment. He claims that these people are rarely seen by psychiatrists and have never been treated successfully.

He gives some identifying characteristics for evil persons. An evil person:

- Projects his or her evils and sins onto others and tries to remove them from others

- Maintains a high level of respectability and lies incessantly in order to do so

- Is consistent in his or her sins. Evil persons are characterized not so much by the magnitude of their sins, but by their consistency

- Is unable to think from other people's viewpoints

Most evil people realize their evil deep within themselves but are unable to tolerate the pain of introspection or admit to themselves that they are evil. Thus, they constantly run away from their evil by putting themselves in a position of "moral superiority" and putting the focus of evil on others. Evil is an extreme form of character disorder.

Scott Peck makes great efforts to keep much of his discussion on a scientific basis. He says that evil arises out of "free choice." He describes it thus: Every person stands at a crossroads, with one path leading to God, and the other path leading to the devil. The path of God is the right path, and accepting this path is akin to submission to a higher power. However, if a person wants to convince himself and others that he has free choice, he would rather take a path which cannot be attributed to its being the right path. Thus, he chooses the path of evil. In this, it is close to the original Judeo-Christian concept of "sin" as a consistent process that leads to failure to reach one's true goals.

Sociopaths

A sociopath is a person with "antisocial" personality disorder, which is a bit more serious than M. Scott Peck's notion of evil above. The basic characteristic of a sociopath is a disregard for the rights of others. It is typified by extreme self-serving behavior and a lack of conscience as well as an inability to empathize with others and to restrain him or herself from, or to feel remorse for, harm personally caused to others. Very often the sociopath may look very charming, friendly, and considerate, but these attitudes turn out to be superficial and even deceptice. They are used as a way of pulling and blinding others to the personal sociopathic agenda behind the surface. Many sociopaths are engaged in alchohol or drug use as a way of heightening their antisocial personality. They want to heighten their antisocial personality because they usually have a low self-esteem, for which they try to compensate through the use of these substrances.

Some sociologists, psychiatrists and neuroscientists have attempted to construct scientific explanations for the development of antisocial personality disorder. Although any diagnosis of sociopathy is sometimes criticized as being, at the present time, no more scientific than calling a person "evil," nevertheless it seems that sociopathy has something to do with moral evil, as long is its basic characteristic is a disregard for the rights of other people.

Evil in business

In business, evil refers to unfair business practices. The most widely agreed on unfair practices are sweatshops and monopolies, but recently the term "evil" has been applied much more broadly, especially in the technology and intellectual property industries. One of the slogans of Google is "Don't Be Evil," in response to much-criticized technology companies such as Microsoft and AOL, and the tag line of independent music recording company Magnatune is "we are not evil," referring to the alleged evils of the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). The economist David Korten has argued that industrial corporations, set up as fictive individuals by law, are required to work only according to the criteria of making profits for their shareholders, meaning they function as sociopathic organizations that inherently do evil in damaging the environment, denying labor justice, and exploiting the powerless.

Evil in a political context

In liberal-democratic societies, many associate evil in politics as revolving around authoritarian and, especially, totalitarian regimes, as well as demagogue leaders, such as the Nazi regime of Adolf Hitler in Germany for its mass genocide of Jews in the Holocaust, war crimes, as well as political and cultural persecution. In World War II and the post war years to present, liberal-democratic societies view Hitler as a symbol of political and social evil in the modern world and is portrayed as such in most media presentations and representations of him. The Communist regime of the Soviet Union has also been considered to be evil by a number of western liberal democracies, especially under the rule of Joseph Stalin, for its mass persecutions of political opponents, religious, and cultural minorities (for example, the Cossacks).

The political writings of Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) in The Prince, often used by Hitler and Mussolini, are considered to be a source of evil in politics, as they often speak of ignoring accepted morals for the pursuit of ultimate power, as "the ends justifies the means." Machiavelli favored a prince creating a climate of fear in order to rule a population, rather than relying on popular support. Machiavelli supports the use of deception and manipulation as means to increase a prince's personal power. All these show little concern for traditional moral and ethical considerations in the thinking of Machiavelli. Thus, when the term "Machiavellian" is used to describe politicians or political policy, it is often being used in a negative context, referring to Machiavelli's support of deception and manipulation to attain and preserve power.

On the other hand, authoritarian, totalitarian, and elements of religious fundamentalist regimes tend to hold a common view that liberal-democratic regimes are evil and blame liberal democracy for high crime rates, profiteering, corporate crime, materialist individualism replacing common bonds of similar people, destruction of culture and its replacement with sleaze. All of which, the regimes claim, will result in the destruction of humanity if liberal democracy is not restrained.

Systemic evil

These days, the term "systemic evil" is heard quite often. It refers to moral evil committed by an organization or a social institution or system. Traditionally, moral evil has been regarded mainly as something committed by an individual person, but systemic evil is a social sin coming from a system collectively. An organization or a social institution or system usually has its own culture, and its members tend to be, psychologically, very easily influenced by it. If the culture is dominated by any unhealthy ideologies or thoughts, such as totalitarianism, authoritarianism, institutionalism, mammonism, racism, and sexism, then the organization or social institution as a whole is found to be collectively committing systemic evil, and its members are consciously or unconsciously participating in the evil. Imperialism, Communism, Nazism, sociopathic industrial corporations, inflexible church institutions, and the Ku Klux Klan are some of its examples. This evil was already pointed out by Walter Rauschenbusch early in the twentieth century, who said that it exerts the "super-personal forces of evil."[3] Although this evil was touched upon to some degree in the above discussion of evil in business and politics, it deserves a separate discussion here because its fearsome implications are taken seriously by many people today. It is more and more understood that sin is not only personal, but also social and collective.

Some issues on evil

The origin of evil

Those who believe, as in monotheistic religions, that God is omnipotent and good, usually ask why, then, evil was originated in the world. Couldn't such a God have prevented evil from occurring? This is what is called the theodicy question, and it asks how to solve the problem of the contradiction of the three statements: 1) That God is omnipotent; 2) that God is good; and 3) that evil actually exists. Traditionally, there are three logical ways to address the problem. A first way is to qualify or deny the omnipotence of God, that is, to regard God as a finite God. Various forms of dualism, such as Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism, are its examples, and even some Christians such as Edwin Lewis have taken this dualistic position.[4] A second way is to qualify or negate the total goodness of God, that is, to say that God must be evil as well as good. This position has been taken by Christians like Frederick Sontag.[5] A third logical way is to qualify the existence of evil, by saying that evil is just non-being or privation of good. Many famous theologians such as Augustine and Thomas Aquinas adhere to this position, which has been quite widespread in Christianity. But, these three traditional ways have been criticized of being just logical answers incapable of actually eradicating evil in the world. Evil is still there.

These days, therefore, a possibly better approach is increasingly appreciated, and it is the free-will defense in its various forms. This defense, anyway, has already been largely adopted by the monotheistic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, because, as was seen above, they teach that humans chose evil through their God-given free will. It attempts to defend God's omnipotence and goodness, placing the possibility of evil only in human free will, which can choose good or evil. It usually argues also that, so far, there has been no free will which always chooses good. Alvin Plantinga has philosophically articulated this defense in his God, Freedom, and Evil.[6] And, to this free-will defense a new flavor has been added by people such as Kenneth Surin in their assertion that, instead of just intellectually discussing about the origination of evil from free will, people should make positive use of their free will to "practically" help to get rid of evil, by committing themselves to, being present with, and showing the suffering love of God to, the victim of evil.[7] This trend is called "practical" theodicy.

The free-will defense, however, seems to have at least one weakness: It places the possibility of evil only in free will, neglecting any influence of temptation from outside. According to Augustine, free will's moral choice of evil has no efficient cause whatsoever and its cause is "deficient" in that it simply comes from the finitude of free will: "Let no one, therefore, look for an efficient cause of the evil will; for it is not efficient, but deficient, as the will itself is not an effecting of something, but a defect."[8] Interestingly, here lies some relevance of metaphysical evil, which itself is not evil, to the origin of evil. But, the weakness of the free-defense is evident from the widely known biblical account of how Eve was tempted by the serpent (a fallen angel) to sin and how Adam was then tempted by Eve to sin (Genesis 1:1-13). If the Bible is correct on the involvement of temptation, and if it is also correct that Adam and Eve were endowed with free will, a reasonable alternative interpretation would be that they fell because some strong power of temptation prevented them from fully exerting their God-given free will for God's purpose. Perhaps, that "strong power of temptation," even stronger than free will, can only come from love, which can eventually drive rational creatures toward a sexual relationship even if it may be entirely opposite to God's purpose. In a nutshell, it is very possible that the human fall in the Garden of Eden took place because free will was not fully used to align love with God's purpose. Perhaps that is the reason why some early Christian Church Fathers, such as St. Clement of Alexandria and St. Ambrose, actually believed that the fall of Adam and Eve was a sexual sin.[9] Even in this case, God can still be defended because it can be understood, as many people agree, that God gave humans free will out of his love for them, so that they as his children might successfully use it to become his partners of love.

For the Eastern religions (perhaps except for Confucianism), the above theodicy question does not arise at least for two reasons: 1) Because they do not believe in an monotheistic God of omnipotence and love; and 2) because they treat evil in the world as unreal.

The virulence of evil

Only dualistic religions seem to take evil very seriously; they explain the virulent reality of evil, by attributing it to the God of evil who existed along with the God of good from eternity. Many of the Eastern religions accept evil as an unavoidable consequence of the karma; but, they paradoxically end up treating it as unreal, by accepting evil through one's self-negation. Monotheistic religions refer to a personal identity called Satan as an agent of temptation, but they do not take evil as seriously as dualistic religions do.

Christian theology, for example, has a widely accepted doctrine of evil as non-being, privation of good, absence of good, or diminution of good, thus treating evil as something non-substantial which one does not have to take very seriously. This doctrine was formulated by Augustine, who adopted the Neo-Platonic tenet that all being is good, while only non-being is evil. Augustine treated even moral evil (sin) the same way. According to him, moral evil is simply a diminution of the moral rectitude of free will; so, it is again non-substantial. Furthermore, sin occurs under no influence upon free will. It only occurs through free will's own turning away from good. It only comes from one's free will and not from any temptation from outside. Sin has no efficient cause, as was mentioned above. (This may not sound Augustinian, because Augustine is usually known as a theologian of sin. But note that there was a considerable evolution and shift within his theology as the object of his attention was shifting from Manichaean heresy to Pelagian heresy.)

Besides this widely accepted Christian treatment of evil as non-being, there are some who developed ways on their own not to take evil seriously. According to Mary Baker Eddy (1821-1910), founder of Christian Science, evil is ontologically unreal in the world created by God who is absolutely good and perfect. Spinoza (1632-1677), a Jewish philosopher of pantheism, argued that the whole world is divine, having no room for evil.

But, if evil is simply ontologically unreal non-being, privation of good, or absence of good, how can people explain the demonic character of many evils that happen in the world? How can one say that Hitler's sin of killing six million Jews was ontologically unreal? Didn't it truly cause substantial pain and suffering to them and also to others who survived the Holocaust? Today, many people naturally ask this question. Carl Jung (1875-1961), a famous Swiss psychiatrist, decided that the traditional Christian view of evil as a privatio boni is a "morally dangerous" doctrine that "belittles" evil.[10] He felt that evil is as real as good.

Many Muslims and fundamentalist and evangelical Christians, even though they are not dualists, tend to see Satan behind any sinful act, and this would support Jung's observation of the virulence of evil. But, if the sexual interpretation of the human fall by Clement of Alexandria and Ambrose is correct, then it can probably explain the demonic nature of evil even better. For the sexual interpretation makes it reasonable to think that the sinful relationship of sexual love of Adam, Eve, and the fallen angel (Satan) bound all human beings as "brood of vipers" (Matther 3:7) under the reign of Satan. If so, all sins can be understood to take place under the strong influence, and in the real presence, of Satan. This must be why the Bible says that Satan entered Judas Iscariot when he was betraying Jesus (Luke 22:3).

The criterion of evil

What is the criterion by which to determine what is evil? The question, in other words, is whether there is a universal, transcendent definition of evil, or whether evil is determined by one's social or cultural background. C.S. Lewis, in The Abolition of Man, maintained that there are certain acts that are universally considered evil, such as rape and murder.[11] On the other hand, it is hard to find any act that was not acceptable in some society. The Greeks held favorable views regarding homosexual relationships between male youths and adult men. Less than 150 years ago, the United States of America, Great Britain, and many other countries practiced slavery of the African race that lasted for over 400 years. Even the Nazis, during World War II, found genocide acceptable for their purpose, as did the Imperial Japanese Army with the Nanking Massacre. Today, there is strong disagreement as to whether homosexuality and abortion are perfectly acceptable or evils.