Emily Hobhouse

Emily Hobhouse (April 9, 1860—June 8, 1926) was a British welfare campaigner, who is primarily remembered for shedding light on the appalling conditions inside the British concentration camps in South Africa built for Boer women and children during the Second Boer War.

Early life

Born in Liskeard, Cornwall, she was the daughter of an Anglican rector, and sister of Leonard Hobhouse. Her mother died when she was 20, and she spent the next fourteen years looking after her father who was in poor health. When her father died in 1895 she went to Minnesota to perform welfare work amongst Cornish mineworkers living there, the trip having been organised by the wife of the Archbishop of Canterbury. There she became engaged to John Carr Jackson and the couple bought a ranch in Mexico but this did not prosper and the engagement was broken off. She returned to England in 1898 after losing most of her money in a speculative venture.

Her wedding veil (that she never wore) hangs in the head office of the "Oranje Vrouevereniging" (Orange Women's Society) in Bloemfontein, the first women's welfare organisation in the Orange Free State, supposedly as a symbol of her commitment towards the upliftment of women.

Second Anglo-Boer War

When the Second Boer War broke out in October 1899, a Liberal MP, Leonard Courtney, invited Hobhouse to become secretary of the women's branch of the South African Conciliation Committee, of which he was president.

Hobhouse wrote "It was late in the summer of 1900 that I first learnt of the hundreds of Boer women that became impoverished and were left ragged by our military operations… the poor women who were being driven from pillar to post, needed protection and organized assistance" [1].

She set up the South African Women and Children's Distress Fund and sailed for South Africa on 7 December 1900 to supervise its distribution. "I came quite naturally, in obedience to the feeling of unity or oneness of womanhood... it is when the community is shaken to its foundations, that abysmal depths of privation call to each other and that a deeper unity of humanity evinces itself " she wrote later. [2]

When she left England, she only knew about the concentration camp at Port Elizabeth, but on arrival found out about the many other camps (34 in total).

Hobhouse had a letter of introduction to the Cape Colony governor, Alfred Milner from her aunt, the wife of Lord Arthur Hobhouse, himself the son of Henry Hobhouse Permanent Under-Secretary at the Home Office under Sir Robert Peel and who knew Milner. From him she obtained the use of two railway trucks, subject to the army commander, Lord Kitchener's, approval. She received Kitchener's permission two weeks later, although it only allowed her to travel as far as Bloemfontein and take one truck of supplies for the camps, about 12 tons.

Bloemfontein Concentration Camp

She arrived at the camp at Bloemfontein on 24 January 1901 and was shocked by the conditions she encountered: "They went to sleep without any provision having been made for them and without anything to eat or to drink. I saw crowds of them along railway lines in bitterly cold weather, in pouring rain - hungry, sick, dying and dead. Soap was an article that was not dispensed. The water supply was inadequate. No bedstead or mattress was procurable. Fuel was scarce and had to be collected from the green bushes on the slopes of the kopjes (small hills) by the people themselves. The rations were extremely meagre and when, as I frequently experienced, the actual quantity dispensed fell short of the amount prescribed, it simply meant famine." [3]

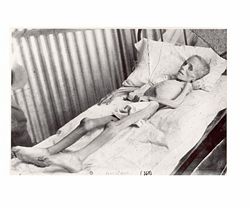

What most distressed Hobhouse was the sufferings of the undernourished children. Diseases such as measles, bronchitis, pneumonia, dysentery and typhoid had invaded the camp with fatal results. There were very few tents who did not house one or more sick persons, most of them children.

In the collection Stemme uit die Verlede ("Voices from the Past"), she recalled the plight of Lizzie van Zyl, a child who died at the Bloemfontein camp. "She was a frail, weak little child in desperate need of good care. Yet, because her mother was one of the "undesirables" due to the fact that her father neither surrendered nor betrayed his people, Lizzie was placed on the lowest rations and so perished with hunger that, after a month in the camp, she was transferred to the new small hospital. Here she was treated harshly. The English disposed doctor and his nurses did not understand her language and, as she could not speak English, labelled her an idiot although she was mentally fit and normal. One day she dejectedly started calling for her mother, when a Mrs Botha walked over to her to console her. She was just telling the child that she would soon see her mother again, when she was brusquely interrupted by one of the nurses who told her not to interfere with the child as she was a nuisance".[4]

When she requested soap for the people, she was told that soap is an article of luxury. She nevertheless succeeded, after a struggle, to have it listed as a necessity, together with straw, more tents and more kettles in which to boil the drinking water. She distributed clothes and supplied pregnant women, who had to sleep on the ground, with mattresses, but she could not forgive what she called Crass male ignorance, helplessness and muddling… I rub as much salt into the sore places in their minds… because it is good for them; but I can't help melting a little when they are very humble and confess that the whole thing is a grievous and gigantic blunder and presents almost insoluble problems, and they don't know how to face it… [5].

Hobhouse also visited camps at Norvalspont, Aliwal North, Springfontein, Kimberley and Orange River.

Fawcett Commission

When she returned to England she received scathing criticism and hostility from the British government and many of the media but eventually succeeded in obtaining more funding to help the victims of the war. The British government eventually agreed to set up the Fawcett Commission to investigate her claims, under Millicent Fawcett, which corroborated her account of the shocking conditions.

She returned to Cape Town in October 1901, was not permitted to land and eventually deported five days after arriving, no reason being given. Hobhouse then went to France where she wrote the book The Brunt of the War and where it fell on what she saw during the war.

Rehabilitation & Reconciliation

After Hobhouse had met the Boer generals she learnt from them that the distress of the women and children in the concentration camps had contributed to their final resolution to surrender to Britain. She saw it then as her mission to assist in healing the wounds inflicted by the war and to support efforts aimed at rehabilitation and reconciliation. With this object in view, she visited South Africa once more in 1903. She decided to set up Boer home industries and to teach young women spinning and weaving when she returned in 1905.

Ill health, from which she never recovered, forced her to return to England in 1908.

She travelled to South Africa again in 1913 for the inauguration of the National Women's Monument in Bloemfontein but had to stop at Beaufort West due to her failing health.

Later life

Hobhouse was an avid opponent of the First World War and protested vigorously against it. Through her offices, thousands of women and children were fed daily for more than a year in central Europe after this war. South Africa contributed liberally towards this effort, and an amount of more than £17 000 was collected by Mrs. President Steyn (who was to remain a life long friend) and sent to Hobhouse for this purpose.

South African reverence

She became an honorary citizen of South Africa for her humanitarian work there. Unbeknownst to her, on the initiative of Mrs R.I Steyn, a sum of £2300 was collected from the Afrikaner nation and with that Emily purchased a house in St Ives, Cornwall, which now forms part of [6]The Porthminster Hotel, where a commemorative plaque situated within what was her lounge, was unveiled by the South African High Commissioner Mr Kent Durr as a tribute to her humanitarianism and heroism during the Anglo Boer War.

Hobhouse died in London in 1926 and her ashes were ensconced in a niche in the National Women's Monument at Bloemfontein.

The southernmost town in Eastern Free State is named Hobhouse, after her.

One of the SA Navy's three submarines was named the "Emily Hobhouse".

External links

- Article about Emily Hobhouse's role on an Anglo-Boer War Memorial site

- Speech given by President Thabo Mbeki in 2004 quoting Emily Hobhouse

- Biography of Hobhouse on "Special South Africans" site

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.