Curtis, Edward S.

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (124 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{copyedited}} | ||

[[Category:Biography]] | [[Category:Biography]] | ||

[[Category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | [[Category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | ||

| Line 18: | Line 19: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Edward Sheriff Curtis''' (February 16, 1868 | + | '''Edward Sheriff Curtis''' (February 16, 1868 - October 19, 1952) was a [[photography|photographer]] of the [[American West]] and of [[Native Americans in the United States|Native American]] peoples. He was born at the time when the native peoples were in transition from a lifestyle where they were free to roam over whichever part of the continent they chose to a questionable future as the land was taken over by white settlers. |

| + | |||

| + | Invited to join [[anthropology|anthropological]] expeditions as a photographer of native tribes, Curtis was inspired to embark on the immense project that became his 20 volume work, ''The North American Indian''. Covering over 80 tribes and comprising over 40,000 photographic images, this monumental work was supported by [[J.P. Morgan]] and President [[Theodore Roosevelt]]. Although today Curtis is regarded as one of the greatest American art photographers, in his time his work was harshly criticized by scholars and the project was a financial disaster. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Nevertheless, Curtis' work is an incredible record of Native American people, of their strength and traditional lifestyles before the white men came. His vision was affected by the times, which viewed the native peoples as a "vanishing race," and Curtis sought to record their ways before they completely vanished, using whatever remained of the old ways and people to do so. Curtis paid people to recreate scenes, and manipulated images to produce the effects he desired. He did not see how these people were to survive under the rule of the Euro-Americans, and so he did not record those efforts. In fact, their traditional lifestyles could not continue, and it was those that Curtis sought to document. Given the tragic history that ensued for these peoples, his work stands as a testament to their strength, pride, honor, beauty, and diversity, a record that can help their descendants regain places of pride in the world and also help others to better appreciate their true value. | ||

==Life== | ==Life== | ||

| − | + | '''Edward Sheriff Curtis''' was born on February 16, 1868, near [[Whitewater, Wisconsin]]. His father, Reverend Johnson Asahel Curtis, was a minister and a [[American Civil War]] veteran. His mother, Ellen Sheriff, was from [[Pennsylvania]], the daughter of immigrants from [[England]]. Edward had an older brother Raphael (Ray), born in 1862, a younger brother Asahel (1875), and a sister Eva (1870). | |

| − | Edward Curtis was born near [[Whitewater, Wisconsin]]. | + | |

| + | Around 1874, the family moved from Wisconsin to rural [[Minnesota]] where they lived in [[Cordova Township, Minnesota|Cordova Township]]. His father worked there as a retail grocer and served as pastor of the local church.<ref name=pbs>George Horse Capture, [http://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/database/curtis_e.html Shadow Catcher,] American Masters, PBS. Retrieved December 15, 2008.</ref> Edward often accompanied his father on his trips as an evangelist, where he taught Edward [[canoe]]ing, [[camping]] skills, and an appreciation of the outdoors. As a teenager, Edward built his first [[camera]] and became fascinated by [[photography]]. He learned how to process prints by working as an [[apprentice]] photographer in [[St. Paul, Minnesota|St. Paul]]. Due to his father's failing health and his older brother having married and moved to [[Oregon]], Edward became responsible to support the family. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1887, Edward and his father traveled west to [[Washington territory]] where they settled in the [[Puget Sound]] area, building a [[log cabin]]. The rest of the family joined them in the spring of 1888; however Rev. Curtis died of [[pneumonia]] days after their arrival. Edward purchased a new camera and became a partner in a photographic studio with Rasmus Rothi. After about six months, Curtis left Rothi and formed a new partnership with Thomas Guptill. The new studio was called Curtis and Guptill, Photographers and Photoengravers.<ref name=loc/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1892, Edward married [[Clara J. Phillips]], who had moved to the area with her family. Together they had four children: Harold (1893), Elizabeth M. (Beth) (1896), Florence (1899), and Katherine (Billy) (1909). In 1896, the entire family moved to a new house in [[Seattle]]. The household then included Edward's mother, Ellen Sheriff; Edward's sister, Eva Curtis; Edward's brother, [[Asahel Curtis]]; Clara's sisters, Susie and Nellie Phillips; and Nellie's son, William. | ||

| − | + | Gupthill left the photographic studio in 1897, and Curtis continued the business under his own name, employing members of his family to assist him. The studio was very successful. However, Curtis and his younger brother, Asahel, had a falling out over photographs Asahel took in the [[Yukon]] of the [[Gold Rush]]. Curtis took credit for the images, claiming that Asahel was acting as an employee of his studio. The two brothers reportedly never spoke to each other again. | |

| − | + | Curtis was able to persuade [[J. P. Morgan]] to finance an ambitious project to photograph [[Native American]] cultures. This work became ''The North American Indian''. Curtis hired [[Adolph Muhr]], a talented photographer, to run the Curtis Studio while he traveled taking photographs. Initially, Clara and their children accompanied Curtis on his trips, but after their son Harold nearly died from [[typhoid]] on one of the trips, she remained in Seattle with the children. Curtis had hired [[William Myers]], a Seattle [[newspaper]] reporter and [[stenography|stenographer]], to act as his field assistant and the fieldwork continued successfully. When Curtis was not in the field, he and his assistants worked constantly to prepare the text to accompany the photographs. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | His last child, Katherine, was born in 1909, while Curtis was in the field. They rarely met during her childhood. Finally, tired of being alone, Clara filed for [[divorce]] on October 16, 1916. In 1919, she was granted the divorce and was awarded their house, Curtis' photographic studio, and all of his original negatives as her part of the settlement. Curtis went with his daughter Beth to the studio and, after copying some of the negatives, destroyed all of his original glass negatives rather than have them become the property of his ex-wife. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Curtis moved to [[Los Angeles]] with his daughter Beth, and opened a new photo studio. To earn money he worked as an assistant cameraman for [[Cecil B. DeMille]] and was an uncredited assistant cameraman in the 1923 filming of ''The Ten Commandments''. To continue financing his North American Indian project Curtis produced a Magic Lantern slide show set to music entitled ''A Vanishing Race'' and an ethnographic motion picture ''In the Land of the Head-Hunters'' and some fictional books on Native American life. However, these were not financially successful and on October 16, 1924, Curtis sold the rights to ''In the Land of the Head-Hunters'' to the [[American Museum of Natural History]]. He was paid $1,500 for the master print and the original camera negative. It had cost him over $20,000 to film.<ref name=makepeace>Anne Makepeace, ''Edward S. Curtis: Coming to Light'' (National Geographic, 2001, ISBN 0792264045).</ref> | |

| − | + | In 1927, after returning from [[Alaska]] to Seattle with his daughter, Beth Curtis was arrested for failure to pay alimony over the preceding seven years. The charges were later dropped. That Christmas, the family was reunited at daughter Florence's home in [[Medford, Oregon]]. This was the first time since the divorce that Curtis was with all of his children at the same time, and it had been thirteen years since he had seen Katherine. | |

| − | In | ||

| − | + | In 1928, desperate for cash, Edward sold the rights to his project ''The North American Indian'' to [[J. P. Morgan, Jr.|J.P Morgan's son]]. In 1930, he published the concluding volume. In total about 280 sets were sold—a financial disaster. | |

| − | On October 19, 1952, at the age of 84, Curtis died of a heart attack in [[Whittier, California]] in the home of his daughter, Beth. He was buried at [[Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Hollywood Hills)|Forest Lawn Memorial Park]] in Hollywood Hills, California. | + | |

| − | <blockquote> | + | In 1932 his ex-wife, Clara, drowned while rowing in [[Puget Sound]], and his daughter, Katherine moved to California to be closer to her father and her sister, Beth.<ref name=makepeace/> |

| − | Edward S. Curtis, internationally known authority on the history of the North American Indian, died today at the home of a daughter, Mrs. Bess Magnuson. His age was 84. Mr. Curtis devoted his life to compiling Indian history. His research was done under the patronage of the late financier, [[J. Pierpont Morgan]]. The foreward | + | |

| + | On October 19, 1952, at the age of 84, Curtis died of a [[heart attack]] in [[Whittier, California]], in the home of his daughter, Beth. He was buried at [[Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Hollywood Hills)|Forest Lawn Memorial Park]] in Hollywood Hills, California. A terse [[obituary]] appeared in ''[[The New York Times]]'' on October 20, 1952: | ||

| + | <blockquote>Edward S. Curtis, internationally known authority on the history of the North American Indian, died today at the home of a daughter, Mrs. Bess Magnuson. His age was 84. Mr. Curtis devoted his life to compiling Indian history. His research was done under the patronage of the late financier, [[J. Pierpont Morgan]]. The foreward for the monumental set of Curtis books was written by President [[Theodore Roosevelt]]. Mr. Curtis was also widely known as a photographer.<ref name=obit>''The New York Times, [http://xroads.virginia.edu/~MA02/daniels/curtis/obituary.html Edward S. Curtis,] October 20, 1952. Retrieved December 15, 2008.</ref> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

==Work== | ==Work== | ||

| + | [[File:Indian Days of the Long Ago.jpg|thumb|right|''Indian Days of the Long Ago,'' 1915]] | ||

| + | [[Image:In the Land of the Head-Hunters.jpg|thumb|''In the Land of the Head-hunters,'' 1915]] | ||

| + | After moving to the Northwest, Curtis embarked on his career in [[photography]]. He was able to establish a successful studio and became a noted [[portrait]] photographer. In 1895, Curtis met and photographed [[Princess Angeline]] (aka Kickisomlo), the daughter of [[Chief Sealth]] of [[Seattle]]. This was his first portrait of a [[Native Americans in the United States|Native American]]. He won prizes for his photographs, including one entitled, ''Angeline Digging Clams''. | ||

| − | + | In 1898, Curtis came upon a small group of scientists climbing [[Mount Rainier]]. The group included [[George Bird Grinnell]], editor of ''[[Forest and Stream]]'', founder of the [[Audubon Society]], and [[anthropology|anthropologist]] specializing in the culture of [[Plains Indians]]. Also in the party was [[Clinton Hart Merriam]], head of the U. S. Biological Survey and one of the early founders of the [[National Geographic Society]]. They asked Curtis to join the [[Harriman Alaska Expedition|Harriman Expedition]] to [[Alaska]] as a photographer the following year. This afforded Curtis, who had had little formal education, an opportunity to gain an education in [[ethnology]] through the formal lectures that were offered on board during the voyage. | |

| − | In | + | |

| + | In 1900, Grinnell invited Curtis to join an expedition to photograph the Piegan [[Blackfeet]] in Montana. There, he witnessed the [[Sun Dance]] performed, a transforming experience that inspired him to undertake his project, ''The North American Indian:'' | ||

| + | <blockquote>Curtis appears to have experienced a sense of mystical communion with the Indians, and out of it, together with Grinnell's tutelage and further experience in the Southwest, came his developing conception of a comprehensive written and photographic record of the most important Indian peoples west of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers who still, as he later put it retained "to a considerable degree their primitive customs and traditions."<ref name=gidley>Mick Gidley, [http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/award98/ienhtml/essay1.html Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) and ''The North American Indian,''] Edward S. Curtis in Context, Library of Congress, January, 2001. Retrieved December 6, 2008.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | To support his massive project, ''The North American Indian,'' Curtis wrote a series of promotional articles for ''Scribner's Magazine'' and books containing fictional accounts of native life before the coming of Europeans. These books, ''Indian Days of the Long Ago'' (1915) and ''In the Land of the Headhunters'' (1915), had the dual purpose of raising money for his project as well as providing the general public with his view of the complexity and beauty of native American culture. He made a motion picture entitled ''In the Land of the Head-Hunters'' documenting the pre-contact lives of the [[Kwakwaka'wakw]] people of [[British Columbia]]. He also produced a "musicale" or "picture-opera," entitled ''A Vanishing Race,'' which combined slides and music, and although this proved popular it was not financially successful. | ||

===''The North American Indian''=== | ===''The North American Indian''=== | ||

| − | [[Image:The North American Indian.jpg|thumb|right|The North American Indian, 1907]] | + | [[Image:The North American Indian.jpg|thumb|right|''The North American Indian'', 1907]] |

| − | In 1906 [[J. P. Morgan]] | + | In 1903, Curtis held an exhibition of his Indian photographs and then traveled to [[Washington, D.C.]] in an attempt to obtain financing from the [[Smithsonian Institution]]'s Bureau of Ethnology for his North American Indian project. There he encountered [[Frederick Webb Hodge]], a highly respected [[ethnology|ethnologist]] who later served as editor for the project. |

| − | < | + | |

| + | Curtis was invited by President [[Theodore Roosevelt]] to photograph his family in 1904, at which time Roosevelt encouraged Curtis to proceed with ''The North American Indian'' project. Curtis took what became a legendary photograph of the aged [[Apache]] chief [[Geronimo]], and was invited to photograph Geronimo along with five other chiefs on horseback on the White House lawn in honor of Roosevelt's 1905 inauguration. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Roosevelt wrote a letter of recommendation for Curtis to promote his project. With this, in 1906, Curtis was able to persuade [[J. P. Morgan]] to provide $75,000 to produce his photographic series.<ref name=nyt1>''The New York Times,'' [http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9A07E3D6143EE233A25755C0A9609C946997D6CF American Indian in "Photo History;" Mr. Edward Curtis's $3,000 Work on the Aborigine a Marvel of Pictorial Record,] June 6, 1908. Retrieved January 3, 2009.</ref> It was to be in 20 volumes with 1,500 photographs. Morgan was to receive 25 sets and 500 original prints as his method of repayment. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Curtis' goal was not just to photograph, but to document, as much Native American traditional life as possible before that way of life disappeared due to [[assimilation]] into the dominant white culture (or became extinct): | ||

| + | <blockquote>The information that is to be gathered … respecting the mode of life of one of the great races of mankind, must be collected at once or the opportunity will be lost.<ref>Edward S. Curtis, [http://xroads.virginia.edu/~MA02/daniels/curtis/vol1/vol1_intro.html General Introduction,] ''The North American Indian, Volume 1'' (Norwood, MA: The Plimpton Press, 1907). Retrieved January 4, 2009.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Curtis made over 10,000 wax cylinder recordings of native languages and music. He took over 40,000 photographic images from over 80 tribes. He recorded tribal lore and history, and he described traditional foods, housing, garments, recreation, ceremonies, and funeral customs. He wrote biographical sketches of tribal leaders, and his material, in most cases, is the only recorded history.<ref name=makepeace/> In this way, Curtis intended that his series be "both the most comprehensive compendium possible and to present, in essence, nothing less than the very spirit of the Indian people."<ref name=gidley/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | His view was that the Native Americans were "vanishing"—either through assimilation into the white culture or by extinction. His feelings about this seem paradoxical. On the one hand, he seems to have believed that they were in some sense "inferior," and thus—according to the doctrine of "survival of the fittest"—they would surely not survive unless they adapted to the ways of white culture, and that adaptation should be forcible if necessary.<ref name=gidley/> Yet, he was horrified when he heard of the mistreatment of California Indians. He certainly regarded the loss of native culture with nostalgia, mixed with admiration and fascination for their spirituality and the courage of their warriors, many of whom he photographed in their old age. His keynote photograph for ''The North American Indian'' reflects this sentiment—entitled ''The Vanishing Race,'' it portrays a group of [[Navajo]]s entering a canyon enshrouded in mist with one head turned to look back in regret. | ||

| − | + | In all, this project took Curtis and his team 30 years to complete the 20 volumes. Curtis traveled to over 80 tribal groups, ranging from the [[Eskimo]] in the far north, the [[Kwakwaka'wakw]], [[Nez Perce]], and [[Haida]] of the northwest, the [[Yurok]] and [[Achomawi]] of [[California]], the [[Hopi]], [[Zuni]], and [[Navajo]] of the Southwest, to the [[Apache]], [[Sioux]], [[Crow]], and [[Cheyenne]] of the [[Great Plains]]. He photographed the significant leaders such as [[Geronimo]], [[Red Cloud]], and [[Chief Joseph]]. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | For this project Curtis gained not only the financial support of J. P. Morgan, but also the endorsement of President [[Theodore Roosevelt]] who wrote a [[foreword]] to the series. However, ''The North American Indian'' was too expensive and took too long to produce to be a success. After the final volume was published in 1930, Curtis and his work fell into obscurity. | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Critique== |

| − | + | Curtis has been praised as a gifted photographer but also criticized by [[ethnology|ethnologists]] for manipulating his images. It has been suggested that he altered his pictures to create an ethnographic simulation of Native tribes untouched by Western society. The photographs have also been charged with misrepresenting Native American people and cultures by portraying them according to the popular notions and [[stereotype]]s of the times. | |

| − | + | Although the early twentieth century was a difficult time for most Native communities in America, not all natives were doomed to becoming a "vanishing race."<ref name=vanish>David R.M. Beck, [http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/award98/ienhtml/essay2.html The Myth of the Vanishing Race,] Edward S. Curtis in Context, Library of Congress, February 2001. Retrieved January 8, 2009.</ref> At a time when natives' rights were being denied and their [[treaty|treaties]] were unrecognized by the federal government, many were successfully adapting to western society. By reinforcing the native [[identity]] as the "[[noble savage]]" and a tragic vanishing race, some believe Curtis detracted attention from the true plight of American natives at the time when he was witnessing their squalid conditions on [[Indian reservation|reservations]] first-hand and their attempt to find their place in Western culture and adapt to their changing world.<ref name=vanish/> | |

| − | |||

| − | In many of his images Curtis removed parasols, suspenders, wagons, and other traces of Western and material culture from his pictures. | + | In many of his images Curtis removed parasols, suspenders, wagons, and other traces of Western and material culture from his pictures. For example, in his photogravure entitled ''In a Piegan Lodge,'' published in ''The North American Indian,'' Curtis retouched the image to remove a clock between the two men seated on the ground.<ref>Library of Congress, [http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/curt:@field(DOCID+@lit(cp06005)) ''In a Piegan Lodge,''] Edward S. Curtis's The North American Indian: Photographic Images, American Memory. Retrieved January 8, 2009.</ref><ref>Gerald Vizenor, [http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/award98/ienhtml/essay3.html Edward Curtis: Pictorialist and Ethnographic Adventurist,] Edward S. Curtis in Context, Library of Congress, October, 2000. Retrieved January 8, 2009. </ref> |

| − | He also is known to have paid natives to pose in staged scenes, | + | He also is known to have paid natives to pose in staged scenes, dance, and participate in simulated ceremonies.<ref>Pamela Michaelis, [http://www.collectorsguide.com/fa/fa047.shtml The Shadow Catcher—Edward Sheriff Curtis,] ''The Collector’s Guide to Santa Fe and Taos—Volume 7,'' July 7, 2008. Retrieved January 8, 2009.</ref> In Curtis' picture ''Oglala War-Party,'' the image shows ten Oglala men wearing feather [[headdress]]es, on horseback riding downhill. The photo caption reads, "a group of Sioux warriors as they appeared in the days of inter tribal warfare, carefully making their way down a hillside in the vicinity of the enemy's camp."<ref>Library of Congress, [http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/curt:@field(DOCID+@lit(cp03002)) ''Oglala War-Party,''] Edward S. Curtis's The North American Indian: Photographic Images, American Memory. Retrieved January 8, 2009.</ref> In truth the photograph was taken in 1907 when they had been relegated to reservations and warring between tribes had ended. |

| + | Indeed, many of his images are reconstructions of a culture already gone but not yet forgotten. He paid those who knew of the old ways to reenact them as a permanent record, producing masterpieces such as ''Fire-drill—Koskimo''.<ref>Library of Congress, [http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?curt:1:./temp/~ammem_ccKA:: ''Fire-drill—Koskimo,''] Edward S. Curtis's The North American Indian: Photographic Images, American Memory. Retrieved January 8, 2009.</ref> Thus, when he asked a [[Kwakwaka'wakw]] man to light a fire in the traditional way, drilling one piece of wood into another with kindling beside it to catch the sparks, while wearing the traditional clothes of his ancestors, "it is a clear and accurate reconstruction by someone who knows what he is doing."<ref name=gidley/> This was Curtis' goal: To document the mystical and majestic qualities of the native cultures before they were entirely lost. | ||

==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

| − | + | In 1935, the rights and remainder of Curtis' unpublished material were sold by the estate of [[J. P. Morgan]] to the Charles E. Lauriat Company in [[Boston]] for $1,000 plus a percentage of any future [[royalties]]. This included 19 complete bound sets of ''The North American Indian,'' thousands of individual paper prints, the copper printing plates, the unbound printed pages, and the original glass-plate negatives. Lauriat bound the remaining loose printed pages and sold them with the completed sets. The remaining material remained untouched in the Lauriat basement in Boston until they were rediscovered in 1972.<ref name=makepeace/> | |

| − | |||

| − | The | ||

| − | + | Around 1970, Karl Kernberger of [[Santa Fe, New Mexico]], went to Boston to search for Curtis' original copper plates and [[photogravure]]s at the Charles E. Lauriat rare bookstore. He discovered almost 285,000 original photogravures as well as all the original copper plates. With Jack Loeffler and David Padwa, they jointly purchased all of the surviving Curtis material owned by Lauriat. The collection was later purchased by another group of investors led by Mark Zaplin of Santa Fe. The Zaplin Group owned the plates until 1982, when they sold them to a California group led by Kenneth Zerbe. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Charles Goddard Weld]] purchased 110 prints that Curtis had made for his 1905-1906 exhibit and donated them to the [[Peabody Essex Museum]]. The 14" by 17" prints are each unique and remain in pristine condition. Clark Worswick, curator of photography for the museum, described them as: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Curtis' most carefully selected prints of what was then his life’s work … certainly these are some of the most glorious prints ever made in the history of the photographic medium. The fact that we have this man’s entire show of 1906 is one of the minor miracles of photography and museology.<ref name=pem>The Peabody Essex Museum, [http://www.pem.org/exhibitions/exhibition.php?id=9 The Master Prints of Edwards S. Curtis: Portraits of Native America.] Retrieved December 25, 2008.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | </blockquote> | ||

| + | In addition to these photographs, the [[Library of Congress]] has a large collection of Curtis' work acquired through copyright deposit from about 1900 through 1930: | ||

| + | <blockquote>The Prints and Photographs Division Curtis collection consists of more than 2,400 silver-gelatin, first generation photographic prints—some of which are sepia-toned—made from Curtis's original glass negatives. … About two-thirds (1,608) of these images were not published in the North American Indian volumes and therefore offer a different and unique glimpse into Curtis's work with indigenous cultures.<ref name=loc>Jennifer Brathovde, [http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/coll/067_curt.html Edward S. Curtis Collection,] Library of Congress, May 2001. Retrieved December 25, 2008.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | = | + | Curtis' project was a massive undertaking, one that appears impossible today. He encountered difficulties of all sorts—problems with the [[weather]], lack of financing, practical difficulties involved in transporting both people and equipment safely across all kinds of inhospitable terrain, and the cooperation of the natives he was documenting. He not only took photographs and video recordings, but also audio recordings of [[song]]s, [[music]], [[story|stories]], and interviews in which they described their lifestyle and history. When ceremonies and other activities were no longer practiced he paid them to reenact the earlier ways of their people. The result is a wealth of historical information as well as beautiful images. However, this is not just the legacy of Curtis, but of the people whose lifestyle he sought to document: |

| + | <blockquote>In spite of the dedication and hardships the photographer had to endure, the ultimate beauty of ''The North American Indian'' lies not only with the genius of Curtis, but also and most importantly, within his subjects. The native beauty, strength, pride, honor, dignity and other admirable characteristics may have been recorded by photographic techniques, but they were first an integral part of the people. While Curtis was a master technician, the Indian people possessed the beauty and their descendants carry on these same traits today.<ref name=pbs/></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | ==Major publications== | |

| − | * | + | ;Books |

| − | + | *Curtis, Edward S. [http://curtis.library.northwestern.edu/ ''The North American Indian''] Originally published in 20 volumes, Norwood, MA: The Plimpton Press, 1907-1930. Northwestern University, Digital Library Collections, 2003. Retrieved December 16, 2008. Taschen, 25th edition, 2007. ISBN 3822847720. | |

| − | + | *Curtis, Edward S. ''Indian Days of the Long Ago''. Roche Press, 2008 (original 1915). ISBN 1408669870. | |

| − | + | *Curtis, Edward S. ''In the Land of the Headhunters''. Ten Speed Press, 1985 (original 1915). ISBN 0913668478. | |

| − | + | ;Movie | |

| − | + | *Curtis, Edward S. [http://www.curtisfilm.rutgers.edu/index.php In the Land of the Head Hunters] [[documentary film]] showing the lives of the [[Kwakwaka'wakw]] peoples of [[British Columbia]], restored by Brad Evans, Aaron Glass, and Andrea Sanborn, 2008 (original 1914; re-released as ''In the Land of the War Canoes'' 1973). In 1999 the film was deemed "culturally significant" by the United States [[Library of Congress]] and selected for preservation in the [[National Film Registry]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Image gallery== | ==Image gallery== | ||

| − | Examples of | + | Examples of photographs taken by Curtis. |

<gallery> | <gallery> | ||

Image:Canyon de Chelly, Navajo.jpg | Image:Canyon de Chelly, Navajo.jpg | ||

Image:The Scout - Apache.jpg | Image:The Scout - Apache.jpg | ||

| − | Image:A smoky day at the Sugar | + | Image:A smoky day at the Sugar Bowl—Hupa.jpg |

Image:Navajo medicine man.jpg | Image:Navajo medicine man.jpg | ||

Image:Whitemanrunshim.jpg | Image:Whitemanrunshim.jpg | ||

Image:Nez Perce warrior on horse.jpg | Image:Nez Perce warrior on horse.jpg | ||

Image:Crow s heart, Mandan.JPG | Image:Crow s heart, Mandan.JPG | ||

| − | |||

Image:Food caches, Hooper Bay, Alaska.jpg | Image:Food caches, Hooper Bay, Alaska.jpg | ||

| − | |||

Image:Fishing with gaff hook.png | Image:Fishing with gaff hook.png | ||

Image:Mandan girls gathering berries.JPG | Image:Mandan girls gathering berries.JPG | ||

| − | |||

Image:Zuni-girl-with-jar.png | Image:Zuni-girl-with-jar.png | ||

Image:Navajo flocks.jpg | Image:Navajo flocks.jpg | ||

Image:Navajo sandpainting.jpg | Image:Navajo sandpainting.jpg | ||

| − | |||

Image:Navajo weaver.jpg | Image:Navajo weaver.jpg | ||

Image:Edward S. Curtis Geronimo Apache cp01002v.jpg | Image:Edward S. Curtis Geronimo Apache cp01002v.jpg | ||

Image:NavahoMedicineManCurtis.jpg | Image:NavahoMedicineManCurtis.jpg | ||

Image:Edward S. Curtis Collection People 035.jpg | Image:Edward S. Curtis Collection People 035.jpg | ||

| − | |||

Image:Curtis - Snake priest.JPG | Image:Curtis - Snake priest.JPG | ||

Image:Edward S. Curtis Collection People 002.jpg | Image:Edward S. Curtis Collection People 002.jpg | ||

| Line 164: | Line 146: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | *[ | + | * Beck, David R. M. [https://davidrmbeck.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/myth-of-the-vanishing-race-web-grab.pdf The Myth of the Vanishing Race.] Edward S. Curtis in Context, Library of Congress, February 2001. Retrieved December 6, 2021. |

| + | * Cardozo, Christopher (ed.). ''Sacred Legacy: Edward S Curtis And The North American Indian''. Simon & Schuster, 2000. ISBN 978-0743203746 | ||

| + | * Cardozo, Christopher. ''Edward S. Curtis: The Great Warriors''. Bulfinch, 2004. ISBN 978-0821228944. | ||

| + | * Cardozo, Christopher. ''Edward S. Curtis: The Women''. Bulfinch, 2005. ISBN 978-0821228951. | ||

| + | * Davis, Barbara A. ''Edward S. Curtis: The Life and Times of a Shadow Catcher''. Gordon Fraser, 1986. ISBN 0860920917. | ||

| + | * Gidley, Mick. ''Edward S. Curtis and the North American Indian, Incorporated''. Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0521775731 | ||

| + | * Gulbrandsen, Don. ''Edward Sheriff Curtis: Visions of the First Americans''. Chartwell Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0785821144. | ||

| + | * Lawlor, Laurie. ''Shadow Catcher: The Life and Work of Edward S. Curtis''. Bison Books, 2005. ISBN 978-0803280465. | ||

| + | * Makepeace, Anne. ''Edward S. Curtis: Coming to Light''. National Geographic, 2001. ISBN 0792264045 | ||

| + | *''The New York Times'' [http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9A06E2DD1031E233A25755C1A9629C946096D6CF Lives 22 Years with Indians to Get Their Secrets.] Magazine Section. April 16, 1911. Retrieved November 19, 2021. | ||

| + | * Vizenor, Gerald. "Edward Curtis: Pictorialist and Ethnographic Adventurist." Essay based on author’s presentation at an Edward Curtis seminar at the Claremont Graduate University, October 6-7, 2000. | ||

| + | * Worswick, Clark. ''Edward Curtis: The Master Prints''. Arena Editions, 2001. ISBN 978-1892041449 | ||

| − | == | + | ==External links== |

| − | + | All links retrieved February 12, 2024. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

*{{findagrave|7629125}} | *{{findagrave|7629125}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*[http://www.sil.si.edu/Exhibitions/Curtis Smithsonian: Edward Curtis] | *[http://www.sil.si.edu/Exhibitions/Curtis Smithsonian: Edward Curtis] | ||

*[http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/coll/067_curt.html Library of Congress Print Collection: Edward Curtis] | *[http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/coll/067_curt.html Library of Congress Print Collection: Edward Curtis] | ||

| − | + | *[http://curtis.library.northwestern.edu/ The North American Indian] | |

| − | *[http://curtis.library.northwestern.edu/ | + | *[https://web.archive.org/web/20231012031503/http://xroads.virginia.edu/ Comprehensive Online Biography of Curtis] Valerie Daniels. |

| − | *[http://xroads.virginia.edu/ | ||

*{{imdb name|id=0193327|name=Edward Curtis}} | *{{imdb name|id=0193327|name=Edward Curtis}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credits|Edward_S_Curtis|255482298}} | {{Credits|Edward_S_Curtis|255482298}} | ||

Latest revision as of 23:49, 12 February 2024

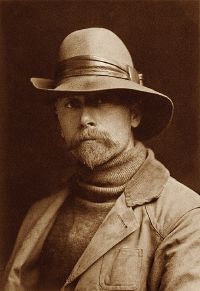

| Edward Sheriff Curtis | |

Self-portrait circa 1889

| |

| Born | February 16, 1868 Whitewater, Wisconsin, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Died | October 19, 1952 Whittier, California, U.S. |

| Occupation | Photographer |

| Spouse(s) | Clara J. Phillips (1874-1932) |

| Children | Harold Curtis (1893-?) Elizabeth M. Curtis (1896-1973) Florence Curtis Graybill (1899-1987) Katherine Curtis (1909-?) |

| Parents | Ellen Sheriff (1844-1912) Johnson Asahel Curtis (1840-1887) |

Edward Sheriff Curtis (February 16, 1868 - October 19, 1952) was a photographer of the American West and of Native American peoples. He was born at the time when the native peoples were in transition from a lifestyle where they were free to roam over whichever part of the continent they chose to a questionable future as the land was taken over by white settlers.

Invited to join anthropological expeditions as a photographer of native tribes, Curtis was inspired to embark on the immense project that became his 20 volume work, The North American Indian. Covering over 80 tribes and comprising over 40,000 photographic images, this monumental work was supported by J.P. Morgan and President Theodore Roosevelt. Although today Curtis is regarded as one of the greatest American art photographers, in his time his work was harshly criticized by scholars and the project was a financial disaster.

Nevertheless, Curtis' work is an incredible record of Native American people, of their strength and traditional lifestyles before the white men came. His vision was affected by the times, which viewed the native peoples as a "vanishing race," and Curtis sought to record their ways before they completely vanished, using whatever remained of the old ways and people to do so. Curtis paid people to recreate scenes, and manipulated images to produce the effects he desired. He did not see how these people were to survive under the rule of the Euro-Americans, and so he did not record those efforts. In fact, their traditional lifestyles could not continue, and it was those that Curtis sought to document. Given the tragic history that ensued for these peoples, his work stands as a testament to their strength, pride, honor, beauty, and diversity, a record that can help their descendants regain places of pride in the world and also help others to better appreciate their true value.

Life

Edward Sheriff Curtis was born on February 16, 1868, near Whitewater, Wisconsin. His father, Reverend Johnson Asahel Curtis, was a minister and a American Civil War veteran. His mother, Ellen Sheriff, was from Pennsylvania, the daughter of immigrants from England. Edward had an older brother Raphael (Ray), born in 1862, a younger brother Asahel (1875), and a sister Eva (1870).

Around 1874, the family moved from Wisconsin to rural Minnesota where they lived in Cordova Township. His father worked there as a retail grocer and served as pastor of the local church.[1] Edward often accompanied his father on his trips as an evangelist, where he taught Edward canoeing, camping skills, and an appreciation of the outdoors. As a teenager, Edward built his first camera and became fascinated by photography. He learned how to process prints by working as an apprentice photographer in St. Paul. Due to his father's failing health and his older brother having married and moved to Oregon, Edward became responsible to support the family.

In 1887, Edward and his father traveled west to Washington territory where they settled in the Puget Sound area, building a log cabin. The rest of the family joined them in the spring of 1888; however Rev. Curtis died of pneumonia days after their arrival. Edward purchased a new camera and became a partner in a photographic studio with Rasmus Rothi. After about six months, Curtis left Rothi and formed a new partnership with Thomas Guptill. The new studio was called Curtis and Guptill, Photographers and Photoengravers.[2]

In 1892, Edward married Clara J. Phillips, who had moved to the area with her family. Together they had four children: Harold (1893), Elizabeth M. (Beth) (1896), Florence (1899), and Katherine (Billy) (1909). In 1896, the entire family moved to a new house in Seattle. The household then included Edward's mother, Ellen Sheriff; Edward's sister, Eva Curtis; Edward's brother, Asahel Curtis; Clara's sisters, Susie and Nellie Phillips; and Nellie's son, William.

Gupthill left the photographic studio in 1897, and Curtis continued the business under his own name, employing members of his family to assist him. The studio was very successful. However, Curtis and his younger brother, Asahel, had a falling out over photographs Asahel took in the Yukon of the Gold Rush. Curtis took credit for the images, claiming that Asahel was acting as an employee of his studio. The two brothers reportedly never spoke to each other again.

Curtis was able to persuade J. P. Morgan to finance an ambitious project to photograph Native American cultures. This work became The North American Indian. Curtis hired Adolph Muhr, a talented photographer, to run the Curtis Studio while he traveled taking photographs. Initially, Clara and their children accompanied Curtis on his trips, but after their son Harold nearly died from typhoid on one of the trips, she remained in Seattle with the children. Curtis had hired William Myers, a Seattle newspaper reporter and stenographer, to act as his field assistant and the fieldwork continued successfully. When Curtis was not in the field, he and his assistants worked constantly to prepare the text to accompany the photographs.

His last child, Katherine, was born in 1909, while Curtis was in the field. They rarely met during her childhood. Finally, tired of being alone, Clara filed for divorce on October 16, 1916. In 1919, she was granted the divorce and was awarded their house, Curtis' photographic studio, and all of his original negatives as her part of the settlement. Curtis went with his daughter Beth to the studio and, after copying some of the negatives, destroyed all of his original glass negatives rather than have them become the property of his ex-wife.

Curtis moved to Los Angeles with his daughter Beth, and opened a new photo studio. To earn money he worked as an assistant cameraman for Cecil B. DeMille and was an uncredited assistant cameraman in the 1923 filming of The Ten Commandments. To continue financing his North American Indian project Curtis produced a Magic Lantern slide show set to music entitled A Vanishing Race and an ethnographic motion picture In the Land of the Head-Hunters and some fictional books on Native American life. However, these were not financially successful and on October 16, 1924, Curtis sold the rights to In the Land of the Head-Hunters to the American Museum of Natural History. He was paid $1,500 for the master print and the original camera negative. It had cost him over $20,000 to film.[3]

In 1927, after returning from Alaska to Seattle with his daughter, Beth Curtis was arrested for failure to pay alimony over the preceding seven years. The charges were later dropped. That Christmas, the family was reunited at daughter Florence's home in Medford, Oregon. This was the first time since the divorce that Curtis was with all of his children at the same time, and it had been thirteen years since he had seen Katherine.

In 1928, desperate for cash, Edward sold the rights to his project The North American Indian to J.P Morgan's son. In 1930, he published the concluding volume. In total about 280 sets were sold—a financial disaster.

In 1932 his ex-wife, Clara, drowned while rowing in Puget Sound, and his daughter, Katherine moved to California to be closer to her father and her sister, Beth.[3]

On October 19, 1952, at the age of 84, Curtis died of a heart attack in Whittier, California, in the home of his daughter, Beth. He was buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Hollywood Hills, California. A terse obituary appeared in The New York Times on October 20, 1952:

Edward S. Curtis, internationally known authority on the history of the North American Indian, died today at the home of a daughter, Mrs. Bess Magnuson. His age was 84. Mr. Curtis devoted his life to compiling Indian history. His research was done under the patronage of the late financier, J. Pierpont Morgan. The foreward for the monumental set of Curtis books was written by President Theodore Roosevelt. Mr. Curtis was also widely known as a photographer.[4]

Work

After moving to the Northwest, Curtis embarked on his career in photography. He was able to establish a successful studio and became a noted portrait photographer. In 1895, Curtis met and photographed Princess Angeline (aka Kickisomlo), the daughter of Chief Sealth of Seattle. This was his first portrait of a Native American. He won prizes for his photographs, including one entitled, Angeline Digging Clams.

In 1898, Curtis came upon a small group of scientists climbing Mount Rainier. The group included George Bird Grinnell, editor of Forest and Stream, founder of the Audubon Society, and anthropologist specializing in the culture of Plains Indians. Also in the party was Clinton Hart Merriam, head of the U. S. Biological Survey and one of the early founders of the National Geographic Society. They asked Curtis to join the Harriman Expedition to Alaska as a photographer the following year. This afforded Curtis, who had had little formal education, an opportunity to gain an education in ethnology through the formal lectures that were offered on board during the voyage.

In 1900, Grinnell invited Curtis to join an expedition to photograph the Piegan Blackfeet in Montana. There, he witnessed the Sun Dance performed, a transforming experience that inspired him to undertake his project, The North American Indian:

Curtis appears to have experienced a sense of mystical communion with the Indians, and out of it, together with Grinnell's tutelage and further experience in the Southwest, came his developing conception of a comprehensive written and photographic record of the most important Indian peoples west of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers who still, as he later put it retained "to a considerable degree their primitive customs and traditions."[5]

To support his massive project, The North American Indian, Curtis wrote a series of promotional articles for Scribner's Magazine and books containing fictional accounts of native life before the coming of Europeans. These books, Indian Days of the Long Ago (1915) and In the Land of the Headhunters (1915), had the dual purpose of raising money for his project as well as providing the general public with his view of the complexity and beauty of native American culture. He made a motion picture entitled In the Land of the Head-Hunters documenting the pre-contact lives of the Kwakwaka'wakw people of British Columbia. He also produced a "musicale" or "picture-opera," entitled A Vanishing Race, which combined slides and music, and although this proved popular it was not financially successful.

The North American Indian

In 1903, Curtis held an exhibition of his Indian photographs and then traveled to Washington, D.C. in an attempt to obtain financing from the Smithsonian Institution's Bureau of Ethnology for his North American Indian project. There he encountered Frederick Webb Hodge, a highly respected ethnologist who later served as editor for the project.

Curtis was invited by President Theodore Roosevelt to photograph his family in 1904, at which time Roosevelt encouraged Curtis to proceed with The North American Indian project. Curtis took what became a legendary photograph of the aged Apache chief Geronimo, and was invited to photograph Geronimo along with five other chiefs on horseback on the White House lawn in honor of Roosevelt's 1905 inauguration.

Roosevelt wrote a letter of recommendation for Curtis to promote his project. With this, in 1906, Curtis was able to persuade J. P. Morgan to provide $75,000 to produce his photographic series.[6] It was to be in 20 volumes with 1,500 photographs. Morgan was to receive 25 sets and 500 original prints as his method of repayment.

Curtis' goal was not just to photograph, but to document, as much Native American traditional life as possible before that way of life disappeared due to assimilation into the dominant white culture (or became extinct):

The information that is to be gathered … respecting the mode of life of one of the great races of mankind, must be collected at once or the opportunity will be lost.[7]

Curtis made over 10,000 wax cylinder recordings of native languages and music. He took over 40,000 photographic images from over 80 tribes. He recorded tribal lore and history, and he described traditional foods, housing, garments, recreation, ceremonies, and funeral customs. He wrote biographical sketches of tribal leaders, and his material, in most cases, is the only recorded history.[3] In this way, Curtis intended that his series be "both the most comprehensive compendium possible and to present, in essence, nothing less than the very spirit of the Indian people."[5]

His view was that the Native Americans were "vanishing"—either through assimilation into the white culture or by extinction. His feelings about this seem paradoxical. On the one hand, he seems to have believed that they were in some sense "inferior," and thus—according to the doctrine of "survival of the fittest"—they would surely not survive unless they adapted to the ways of white culture, and that adaptation should be forcible if necessary.[5] Yet, he was horrified when he heard of the mistreatment of California Indians. He certainly regarded the loss of native culture with nostalgia, mixed with admiration and fascination for their spirituality and the courage of their warriors, many of whom he photographed in their old age. His keynote photograph for The North American Indian reflects this sentiment—entitled The Vanishing Race, it portrays a group of Navajos entering a canyon enshrouded in mist with one head turned to look back in regret.

In all, this project took Curtis and his team 30 years to complete the 20 volumes. Curtis traveled to over 80 tribal groups, ranging from the Eskimo in the far north, the Kwakwaka'wakw, Nez Perce, and Haida of the northwest, the Yurok and Achomawi of California, the Hopi, Zuni, and Navajo of the Southwest, to the Apache, Sioux, Crow, and Cheyenne of the Great Plains. He photographed the significant leaders such as Geronimo, Red Cloud, and Chief Joseph.

For this project Curtis gained not only the financial support of J. P. Morgan, but also the endorsement of President Theodore Roosevelt who wrote a foreword to the series. However, The North American Indian was too expensive and took too long to produce to be a success. After the final volume was published in 1930, Curtis and his work fell into obscurity.

Critique

Curtis has been praised as a gifted photographer but also criticized by ethnologists for manipulating his images. It has been suggested that he altered his pictures to create an ethnographic simulation of Native tribes untouched by Western society. The photographs have also been charged with misrepresenting Native American people and cultures by portraying them according to the popular notions and stereotypes of the times.

Although the early twentieth century was a difficult time for most Native communities in America, not all natives were doomed to becoming a "vanishing race."[8] At a time when natives' rights were being denied and their treaties were unrecognized by the federal government, many were successfully adapting to western society. By reinforcing the native identity as the "noble savage" and a tragic vanishing race, some believe Curtis detracted attention from the true plight of American natives at the time when he was witnessing their squalid conditions on reservations first-hand and their attempt to find their place in Western culture and adapt to their changing world.[8]

In many of his images Curtis removed parasols, suspenders, wagons, and other traces of Western and material culture from his pictures. For example, in his photogravure entitled In a Piegan Lodge, published in The North American Indian, Curtis retouched the image to remove a clock between the two men seated on the ground.[9][10]

He also is known to have paid natives to pose in staged scenes, dance, and participate in simulated ceremonies.[11] In Curtis' picture Oglala War-Party, the image shows ten Oglala men wearing feather headdresses, on horseback riding downhill. The photo caption reads, "a group of Sioux warriors as they appeared in the days of inter tribal warfare, carefully making their way down a hillside in the vicinity of the enemy's camp."[12] In truth the photograph was taken in 1907 when they had been relegated to reservations and warring between tribes had ended.

Indeed, many of his images are reconstructions of a culture already gone but not yet forgotten. He paid those who knew of the old ways to reenact them as a permanent record, producing masterpieces such as Fire-drill—Koskimo.[13] Thus, when he asked a Kwakwaka'wakw man to light a fire in the traditional way, drilling one piece of wood into another with kindling beside it to catch the sparks, while wearing the traditional clothes of his ancestors, "it is a clear and accurate reconstruction by someone who knows what he is doing."[5] This was Curtis' goal: To document the mystical and majestic qualities of the native cultures before they were entirely lost.

Legacy

In 1935, the rights and remainder of Curtis' unpublished material were sold by the estate of J. P. Morgan to the Charles E. Lauriat Company in Boston for $1,000 plus a percentage of any future royalties. This included 19 complete bound sets of The North American Indian, thousands of individual paper prints, the copper printing plates, the unbound printed pages, and the original glass-plate negatives. Lauriat bound the remaining loose printed pages and sold them with the completed sets. The remaining material remained untouched in the Lauriat basement in Boston until they were rediscovered in 1972.[3]

Around 1970, Karl Kernberger of Santa Fe, New Mexico, went to Boston to search for Curtis' original copper plates and photogravures at the Charles E. Lauriat rare bookstore. He discovered almost 285,000 original photogravures as well as all the original copper plates. With Jack Loeffler and David Padwa, they jointly purchased all of the surviving Curtis material owned by Lauriat. The collection was later purchased by another group of investors led by Mark Zaplin of Santa Fe. The Zaplin Group owned the plates until 1982, when they sold them to a California group led by Kenneth Zerbe.

Charles Goddard Weld purchased 110 prints that Curtis had made for his 1905-1906 exhibit and donated them to the Peabody Essex Museum. The 14" by 17" prints are each unique and remain in pristine condition. Clark Worswick, curator of photography for the museum, described them as:

Curtis' most carefully selected prints of what was then his life’s work … certainly these are some of the most glorious prints ever made in the history of the photographic medium. The fact that we have this man’s entire show of 1906 is one of the minor miracles of photography and museology.[14]

In addition to these photographs, the Library of Congress has a large collection of Curtis' work acquired through copyright deposit from about 1900 through 1930:

The Prints and Photographs Division Curtis collection consists of more than 2,400 silver-gelatin, first generation photographic prints—some of which are sepia-toned—made from Curtis's original glass negatives. … About two-thirds (1,608) of these images were not published in the North American Indian volumes and therefore offer a different and unique glimpse into Curtis's work with indigenous cultures.[2]

Curtis' project was a massive undertaking, one that appears impossible today. He encountered difficulties of all sorts—problems with the weather, lack of financing, practical difficulties involved in transporting both people and equipment safely across all kinds of inhospitable terrain, and the cooperation of the natives he was documenting. He not only took photographs and video recordings, but also audio recordings of songs, music, stories, and interviews in which they described their lifestyle and history. When ceremonies and other activities were no longer practiced he paid them to reenact the earlier ways of their people. The result is a wealth of historical information as well as beautiful images. However, this is not just the legacy of Curtis, but of the people whose lifestyle he sought to document:

In spite of the dedication and hardships the photographer had to endure, the ultimate beauty of The North American Indian lies not only with the genius of Curtis, but also and most importantly, within his subjects. The native beauty, strength, pride, honor, dignity and other admirable characteristics may have been recorded by photographic techniques, but they were first an integral part of the people. While Curtis was a master technician, the Indian people possessed the beauty and their descendants carry on these same traits today.[1]

Major publications

- Books

- Curtis, Edward S. The North American Indian Originally published in 20 volumes, Norwood, MA: The Plimpton Press, 1907-1930. Northwestern University, Digital Library Collections, 2003. Retrieved December 16, 2008. Taschen, 25th edition, 2007. ISBN 3822847720.

- Curtis, Edward S. Indian Days of the Long Ago. Roche Press, 2008 (original 1915). ISBN 1408669870.

- Curtis, Edward S. In the Land of the Headhunters. Ten Speed Press, 1985 (original 1915). ISBN 0913668478.

- Movie

- Curtis, Edward S. In the Land of the Head Hunters documentary film showing the lives of the Kwakwaka'wakw peoples of British Columbia, restored by Brad Evans, Aaron Glass, and Andrea Sanborn, 2008 (original 1914; re-released as In the Land of the War Canoes 1973). In 1999 the film was deemed "culturally significant" by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.

Image gallery

Examples of photographs taken by Curtis.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 George Horse Capture, Shadow Catcher, American Masters, PBS. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Jennifer Brathovde, Edward S. Curtis Collection, Library of Congress, May 2001. Retrieved December 25, 2008.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Anne Makepeace, Edward S. Curtis: Coming to Light (National Geographic, 2001, ISBN 0792264045).

- ↑ The New York Times, Edward S. Curtis, October 20, 1952. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Mick Gidley, Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) and The North American Indian, Edward S. Curtis in Context, Library of Congress, January, 2001. Retrieved December 6, 2008.

- ↑ The New York Times, American Indian in "Photo History;" Mr. Edward Curtis's $3,000 Work on the Aborigine a Marvel of Pictorial Record, June 6, 1908. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- ↑ Edward S. Curtis, General Introduction, The North American Indian, Volume 1 (Norwood, MA: The Plimpton Press, 1907). Retrieved January 4, 2009.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 David R.M. Beck, The Myth of the Vanishing Race, Edward S. Curtis in Context, Library of Congress, February 2001. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ↑ Library of Congress, In a Piegan Lodge, Edward S. Curtis's The North American Indian: Photographic Images, American Memory. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ↑ Gerald Vizenor, Edward Curtis: Pictorialist and Ethnographic Adventurist, Edward S. Curtis in Context, Library of Congress, October, 2000. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ↑ Pamela Michaelis, The Shadow Catcher—Edward Sheriff Curtis, The Collector’s Guide to Santa Fe and Taos—Volume 7, July 7, 2008. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ↑ Library of Congress, Oglala War-Party, Edward S. Curtis's The North American Indian: Photographic Images, American Memory. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ↑ Library of Congress, Fire-drill—Koskimo, Edward S. Curtis's The North American Indian: Photographic Images, American Memory. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ↑ The Peabody Essex Museum, The Master Prints of Edwards S. Curtis: Portraits of Native America. Retrieved December 25, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beck, David R. M. The Myth of the Vanishing Race. Edward S. Curtis in Context, Library of Congress, February 2001. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- Cardozo, Christopher (ed.). Sacred Legacy: Edward S Curtis And The North American Indian. Simon & Schuster, 2000. ISBN 978-0743203746

- Cardozo, Christopher. Edward S. Curtis: The Great Warriors. Bulfinch, 2004. ISBN 978-0821228944.

- Cardozo, Christopher. Edward S. Curtis: The Women. Bulfinch, 2005. ISBN 978-0821228951.

- Davis, Barbara A. Edward S. Curtis: The Life and Times of a Shadow Catcher. Gordon Fraser, 1986. ISBN 0860920917.

- Gidley, Mick. Edward S. Curtis and the North American Indian, Incorporated. Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0521775731

- Gulbrandsen, Don. Edward Sheriff Curtis: Visions of the First Americans. Chartwell Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0785821144.

- Lawlor, Laurie. Shadow Catcher: The Life and Work of Edward S. Curtis. Bison Books, 2005. ISBN 978-0803280465.

- Makepeace, Anne. Edward S. Curtis: Coming to Light. National Geographic, 2001. ISBN 0792264045

- The New York Times Lives 22 Years with Indians to Get Their Secrets. Magazine Section. April 16, 1911. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- Vizenor, Gerald. "Edward Curtis: Pictorialist and Ethnographic Adventurist." Essay based on author’s presentation at an Edward Curtis seminar at the Claremont Graduate University, October 6-7, 2000.

- Worswick, Clark. Edward Curtis: The Master Prints. Arena Editions, 2001. ISBN 978-1892041449

External links

All links retrieved February 12, 2024.

- Edward S. Curtis at Find A Grave

- Smithsonian: Edward Curtis

- Library of Congress Print Collection: Edward Curtis

- The North American Indian

- Comprehensive Online Biography of Curtis Valerie Daniels.

- Edward Curtis at the Internet Movie Database

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.