Difference between revisions of "Ebla" - New World Encyclopedia

| (46 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}} |

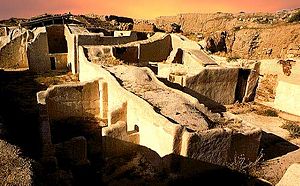

| − | {{ | + | [[Image:Ebla.jpg|thumb|300px|Ebla as it looks today]] |

| − | {{ | ||

| − | [[ | + | '''Ebla''' ([[Arabic Language|Arabic]]: عبيل، إيبلا, modern '''Tell Mardikh,''' [[Syria]]) was an ancient city about 55 km southwest of [[Aleppo]]. It was an important city-state in two periods, first in the late [[3rd millennium B.C.E.|third millennium B.C.E.]], then again between [[1800 B.C.E.|1800]] and 1650 B.C.E. The site is famous today mainly for its well preserved archive of about 17,000 [[Cuneiform (script)|cuneiform tablet]]s, dated from around 2250 B.C.E.., in Sumerian and in [[Eblaite language|Eblaite]]—a previously unknown [[Semitic languages|Semitic]] language. |

| − | + | Around the time the Ebla tablets were created, the city was a major economic center governed by a series of kings who were elected rather than ruling through dynastic succession, until the coming of King Ibrium and his son Ibbi-Sipish. Its [[religion]] appears to have included both Semitic and Sumerian influences, and many ancient biblical personal names and places have been found among the tablets. Ebla was destroyed c. 2200 B.C.E. by the emerging [[Akkad]]ian empire, being rebuilt about four centuries later by the [[Amorites]]. After a second destruction by the [[Hittites]], it existed only as a village and disappeared after around 700 C.E. until its rediscovery in 1964. | |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | The | + | The Ebla tablets represent one of the richest archaeological finds of recent times in terms of the information they yield about the economy, culture, religion, and daily life of the [[Near East]] and [[Mesopotamia]], not to mention Ebla itself. |

==Discovery and excavation== | ==Discovery and excavation== | ||

| − | [[Image:Syria2mil.JPG|thumb|right|275px|Map of Syria in the second millennium B.C.E. | + | [[Image:Syria2mil.JPG|thumb|right|275px|Map of Syria in the second millennium B.C.E. Ebla is shown to the northwest between [[Ugarit]] and Alep/[[Aleppo]].]] |

| − | + | Ebla was well known in concept long before its modern rediscovery, being mentioned in the [[Mari archives]] and several other ancient Mesopotamian texts. [[Akkad]]ian texts from c. 2300 B.C.E. testify to its wide influence and later inscriptions in the annals of [[Thutmose III]] and Hittite texts from Anatolia also speak of the city. | |

| − | In the | + | In 1964, Italian archaeologists from the [[University of Rome La Sapienza]] directed by [[Paolo Matthiae]] began excavating at Tell Mardikh in northern [[Syria]]. In 1968, they recovered a statue dedicated to the goddess [[Ishtar]] bearing the name of [[Ibbit-Lim]], a previously known king of Ebla. This inscription identified the city, long known from [[Egypt]]ian and [[Akkad]]ian inscriptions. |

| − | Archaeologists are divided as to whether the language should be classified as West Semitic or East Semitic | + | In the next decade the team discovered a palace or archive dating approximately from 2500–2000 B.C.E. A cache of about 17,000 well-preserved [[Cuneiform (script)|cuneiform]] tablets were discovered in the ruins.<ref>Matthiae, 1981.</ref> About eighty percent of the tablets are written in Sumerian. The others are in a previously unknown [[Semitic]] language now known as [[Eblaite language|Eblaite]]. Sumerian-Eblaite vocabulary lists were found with the tablets, allowing them to be translated. [[archaeology|Archaeologists]] are divided as to whether the language should be classified as West Semitic or East Semitic. |

| − | The | + | The larger tablets were discovered where they had fallen from archival shelves, allowing the excavators to reconstruct their original position on the shelves, according to subject. The archive includes records relating to provisions and tribute, law cases, diplomatic and trade contacts, and a [[scriptorium]] where apprentice scribes copied texts. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Ebla in the third millennium B.C.E.== | ==Ebla in the third millennium B.C.E.== | ||

| − | The name "Ebla" means "White Rock," and refers to the limestone outcrop on which the city was built. Although the site shows signs of continuous occupation since before 3000 B.C.E., its power grew and reached its | + | The name "Ebla" means "White Rock," and refers to the limestone outcrop on which the city was built. Although the site shows signs of continuous occupation since before 3000 B.C.E., its power grew and reached its greatest height in the second half of the [[3rd millennium B.C.E.|following millennium]]. Ebla's first apogee was between [[2400 B.C.E.|2400]] and 2240 B.C.E. Its name is mentioned in texts from [[Akkad]] around 2300 B.C.E.. Excavations have unearthed [[palace]]s, a [[library]], [[temple]]s, a fortified city wall, and subterranean [[tomb]]s. |

| − | Most of the Ebla | + | Most of the Ebla tablets, which date from the above-mentioned period, are about economic matters. They provide important insights into the everyday life of the inhabitants, as well as the cultural, economic, and political life of ancient northern Syria and [[Near East]]. Besides accounts of state revenues, the texts also include royal letters, Sumerian-Eblaite dictionaries, school texts, and diplomatic documents, such as treaties between Ebla and other towns of the region. |

| − | Ebla's most powerful king | + | The tablets list Ebla's most powerful king as Ebrium, or [[Ibrium]], who concluded the so-called "Treaty with Ashur," which offered the Assyrian king Tudia, the use of a trading post officially controlled by Ebla. The fifth and last king of Ebla during this period was Ibrium's son, Ibbi-Sipish. He was the first Eblaite king to succeed his father in a dynastic line, thus breaking with the established custom of electing its ruler for a fixed term of office lasting seven years. |

| − | + | Some analysts believe this new dynastic tradition may have contributed to the unrest that was ultimately instrumental in the city's decline. In the meantime, however, the reign of Ibbi-Sipish seems to have been a time of relative prosperity, in part because the king was given to frequent travel abroad, leading to greater trade and other diplomatic successes. For example, it was recorded both in Ebla and [[Aleppo]] that he concluded specific treaties between the two cities. | |

===Economy=== | ===Economy=== | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Ebla royal palace.jpg|thumb|300px|The ruins of Ebla's royal palace.]] | |

| + | Ebla in the third millennium was a major commercial center with influence over a number of nearby smaller city-states. Its most important commercial rival was [[Mari, Syria|Mari]]. The Ebla tablets reveal that its inhabitants owned about 200,000 head of mixed cattle ([[sheep]], [[goat]]s, and [[cow]]s). Linen and wool seem to have been its main products. The city also traded in timber from the nearby mountains and perhaps from [[Lebanon]]. Woodworking and metalworking were other important activities, including the smelting of [[gold]], [[silver]], [[copper]], [[tin]], and [[lead]]. Other products included [[olive oil]], [[wine]], and [[beer]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Most of Ebla's trade seems to have been directed toward [[Mesopotamia]], chiefly [[Kish (Sumer)|Kish]], but contacts with [[Egypt]] are also attested by gifts from pharaohs [[Khafra]] and [[Pepi I]]. Handicrafts may also have been a major export. Exquisite artifacts have been recovered from the ruins, including wood furniture inlaid with mother-of-pearl and composite statues created from various colored stones. The artistic style at Ebla may have influenced the quality of work of the Akkadian empire (c. [[2350 B.C.E.|2350]]–2150 B.C.E.). | ||

===Government=== | ===Government=== | ||

| − | + | Ebla's form of government is not completely clear, but in the late third millennium the city appears to have been ruled by a [[merchant]] [[aristocracy]] that elected a king and entrusted the city's defense to paid soldiers. These elected rulers served for a term of seven years. Among the kings mentioned in the tablets are [[Igrish-Halam]], [[Irkab-Damu]], [[Ar-Ennum]], [[Ibrium]], and [[Ibbi-Sipish]]. It was Ibrium who broke with tradition and introduced a dynastic monarchy. He was followed by his son, Ibbi-Sipish. | |

===Religion=== | ===Religion=== | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Ebla ziggurat.jpg|thumb|250px|Ruins of a [[ziggurat]] at Ebla.]] | |

| + | An Eblaite creation hymn was discovered among the tablets, existing in three distinct version, all of which contain the following verse: | ||

| − | + | :''Lord of heaven and earth:'' | |

| + | :''The earth was not, you created it'' | ||

| + | :''The light of day was not, you created it'' | ||

| + | :''The morning light you had not [yet] made exist.'' | ||

| − | + | Its location apparently gave Ebla exposure to several religious cultures. Although Sumerian gods were also honored, the [[Canaan]]ite god [[El]] has been found at the top of a list of deities worshiped there. Other well-known Semitic deities appearing at Ebla include [[Dagan]], [[Ishtar]], and [[Hadad]], plus several Sumerian gods such as ([[Enki]] and [[Ninki]] (Ninlil), and the [[Hurrians|Hurrian]] deities ([[Ashtapi]], [[Hebat]], and [[Ishara]]). Some otherwise unknown gods are also mentioned, namely [[Kura]] and [[Nidakul]]. | |

| − | + | Archaeologist [[Giovanni Pettinato]] has noted a change in the theophoric personal names in many of the tablets from "-el" to "-yah." For example "Mika’el" transforms into "Mikaya." This is considered by some to constitute an early use of the divine name [[Yahu|Yah]], a god who believed to have later emerged as the Hebrew deity [[Yahweh]]. Others have suggested that this shift indicates the popular acceptance of the Akkadian God [[Ea (Babylonian god)|Ea]] (Sumerian: [[Enki]]) introduced from the [[Sargon]]id Empire, which may have been transliterated into Eblaite as YH.<ref>Gordon, 2002.</ref> | |

| − | + | Many [[Old Testament]] personal names that have not been found in other Near Eastern languages have similar forms in Eblaite, including a-da-mu/[[Adam (Bible)|Adam]], h’à-wa /[[Eve (name)|Eve]], Abarama/[[Abraham]], [[Bilhah]], [[Ishmael]], [[Israel|Isûra-el]], [[Esau]], Mika-el/[[Michael]], Mikaya/[[Michaiah]], [[Saul]], and [[David]]). Also mentioned in the Ebla tablets are many biblical locations: For example, Ashtaroth, [[Sinai]], [[Jerusalem]] (Ye-ru-sa-lu-um), [[Hazor]], [[Lachish]], [[Gezer]], [[Dor]], [[Megiddo]], [[Joppa]], and so on. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Destruction and reemergence== |

| − | [[Sargon of Akkad]] and his grandson [[Naram-sin]], the conquerors of much of Mesopotamia, | + | [[Sargon of Akkad]] and his grandson [[Naram-sin]], the conquerors of much of [[Mesopotamia]], both claim to have destroyed Ebla. The exact date of destruction is the subject of continuing debate, but 2240 B.C.E. is a probable candidate. |

| − | + | Over the next several centuries, Ebla was able to regain some economic importance in the region, but never reached its former glory. It is possible the city had economic ties with the nearby city of [[Urshu]], as is documented by economic texts from [[Drehem]], a suburb of [[Nippur]], and from findings in [[Kultepe]]/Kanesh. | |

| − | |||

| − | Ebla | + | Ebla's second apogee lasted from about [[1850 B.C.E.|1850]] to 1600 B.C.E. During this period the people of Ebla were apparently [[Amorite]]s. Ebla is mentioned in texts from [[Alalakh]] around 1750 B.C.E.[[Ibbit-Lim]] was the first known king of Ebla during this time. |

| − | Ebla never recovered from its second destruction. | + | The city was destroyed again in the turbulent period of [[1650 B.C.E.|1650]]–1600 B.C.E., by a [[Hittites|Hittite]] king ([[Mursili I]] or [[Hattusili I]]). Ebla never recovered from its second destruction. It continued only as a small village until the seventh century C.E., then was deserted and forgotten until its archaeological rediscovery. |

| + | |||

| + | ==See also== | ||

| + | *[[Sumerian Civilization]] | ||

| + | *[[Biblical archaeology]] | ||

| + | *[[Sargon I]] | ||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

| − | + | <references/> | |

== References == | == References == | ||

| − | * | + | * Cornelius, Izak, and Louis C. Jonker. ''From Ebla to Stellenbosch: Syro-Palestinian Religions and the Hebrew Bible''. Abhandlungen des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins, Bd. 37. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz in Kommission, 2008. ISBN 978-3447057769 |

| − | * Gordon, Cyrus and Rendsburg | + | * Gordon, Cyrus Herzl, and Gary Rendsburg. ''Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language''. Winona Lake, Ind: Eisenbrauns, 2002. ISBN 978-1575060606 |

| − | * | + | * Matthiae, Paolo. ''Ebla: An Empire Rediscovered''. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1981. ISBN 978-0385129046 |

| − | * Pettinato, Giovanni ''The Archives of Ebla: An Empire Inscribed in Clay'' | + | * Pettinato, Giovanni. ''The Archives of Ebla: An Empire Inscribed in Clay''. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1981. ISBN 978-0385131520 |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:history]] | [[Category:history]] | ||

| + | [[Category:literature]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Bible]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Archaeological sites]] | ||

{{Credit|210267242}} | {{Credit|210267242}} | ||

Latest revision as of 17:22, 11 October 2020

Ebla (Arabic: عبيل، إيبلا, modern Tell Mardikh, Syria) was an ancient city about 55 km southwest of Aleppo. It was an important city-state in two periods, first in the late third millennium B.C.E., then again between 1800 and 1650 B.C.E. The site is famous today mainly for its well preserved archive of about 17,000 cuneiform tablets, dated from around 2250 B.C.E., in Sumerian and in Eblaite—a previously unknown Semitic language.

Around the time the Ebla tablets were created, the city was a major economic center governed by a series of kings who were elected rather than ruling through dynastic succession, until the coming of King Ibrium and his son Ibbi-Sipish. Its religion appears to have included both Semitic and Sumerian influences, and many ancient biblical personal names and places have been found among the tablets. Ebla was destroyed c. 2200 B.C.E. by the emerging Akkadian empire, being rebuilt about four centuries later by the Amorites. After a second destruction by the Hittites, it existed only as a village and disappeared after around 700 C.E. until its rediscovery in 1964.

The Ebla tablets represent one of the richest archaeological finds of recent times in terms of the information they yield about the economy, culture, religion, and daily life of the Near East and Mesopotamia, not to mention Ebla itself.

Discovery and excavation

Ebla was well known in concept long before its modern rediscovery, being mentioned in the Mari archives and several other ancient Mesopotamian texts. Akkadian texts from c. 2300 B.C.E. testify to its wide influence and later inscriptions in the annals of Thutmose III and Hittite texts from Anatolia also speak of the city.

In 1964, Italian archaeologists from the University of Rome La Sapienza directed by Paolo Matthiae began excavating at Tell Mardikh in northern Syria. In 1968, they recovered a statue dedicated to the goddess Ishtar bearing the name of Ibbit-Lim, a previously known king of Ebla. This inscription identified the city, long known from Egyptian and Akkadian inscriptions.

In the next decade the team discovered a palace or archive dating approximately from 2500–2000 B.C.E. A cache of about 17,000 well-preserved cuneiform tablets were discovered in the ruins.[1] About eighty percent of the tablets are written in Sumerian. The others are in a previously unknown Semitic language now known as Eblaite. Sumerian-Eblaite vocabulary lists were found with the tablets, allowing them to be translated. Archaeologists are divided as to whether the language should be classified as West Semitic or East Semitic.

The larger tablets were discovered where they had fallen from archival shelves, allowing the excavators to reconstruct their original position on the shelves, according to subject. The archive includes records relating to provisions and tribute, law cases, diplomatic and trade contacts, and a scriptorium where apprentice scribes copied texts.

Ebla in the third millennium B.C.E.

The name "Ebla" means "White Rock," and refers to the limestone outcrop on which the city was built. Although the site shows signs of continuous occupation since before 3000 B.C.E., its power grew and reached its greatest height in the second half of the following millennium. Ebla's first apogee was between 2400 and 2240 B.C.E. Its name is mentioned in texts from Akkad around 2300 B.C.E. Excavations have unearthed palaces, a library, temples, a fortified city wall, and subterranean tombs.

Most of the Ebla tablets, which date from the above-mentioned period, are about economic matters. They provide important insights into the everyday life of the inhabitants, as well as the cultural, economic, and political life of ancient northern Syria and Near East. Besides accounts of state revenues, the texts also include royal letters, Sumerian-Eblaite dictionaries, school texts, and diplomatic documents, such as treaties between Ebla and other towns of the region.

The tablets list Ebla's most powerful king as Ebrium, or Ibrium, who concluded the so-called "Treaty with Ashur," which offered the Assyrian king Tudia, the use of a trading post officially controlled by Ebla. The fifth and last king of Ebla during this period was Ibrium's son, Ibbi-Sipish. He was the first Eblaite king to succeed his father in a dynastic line, thus breaking with the established custom of electing its ruler for a fixed term of office lasting seven years.

Some analysts believe this new dynastic tradition may have contributed to the unrest that was ultimately instrumental in the city's decline. In the meantime, however, the reign of Ibbi-Sipish seems to have been a time of relative prosperity, in part because the king was given to frequent travel abroad, leading to greater trade and other diplomatic successes. For example, it was recorded both in Ebla and Aleppo that he concluded specific treaties between the two cities.

Economy

Ebla in the third millennium was a major commercial center with influence over a number of nearby smaller city-states. Its most important commercial rival was Mari. The Ebla tablets reveal that its inhabitants owned about 200,000 head of mixed cattle (sheep, goats, and cows). Linen and wool seem to have been its main products. The city also traded in timber from the nearby mountains and perhaps from Lebanon. Woodworking and metalworking were other important activities, including the smelting of gold, silver, copper, tin, and lead. Other products included olive oil, wine, and beer.

Most of Ebla's trade seems to have been directed toward Mesopotamia, chiefly Kish, but contacts with Egypt are also attested by gifts from pharaohs Khafra and Pepi I. Handicrafts may also have been a major export. Exquisite artifacts have been recovered from the ruins, including wood furniture inlaid with mother-of-pearl and composite statues created from various colored stones. The artistic style at Ebla may have influenced the quality of work of the Akkadian empire (c. 2350–2150 B.C.E.).

Government

Ebla's form of government is not completely clear, but in the late third millennium the city appears to have been ruled by a merchant aristocracy that elected a king and entrusted the city's defense to paid soldiers. These elected rulers served for a term of seven years. Among the kings mentioned in the tablets are Igrish-Halam, Irkab-Damu, Ar-Ennum, Ibrium, and Ibbi-Sipish. It was Ibrium who broke with tradition and introduced a dynastic monarchy. He was followed by his son, Ibbi-Sipish.

Religion

An Eblaite creation hymn was discovered among the tablets, existing in three distinct version, all of which contain the following verse:

- Lord of heaven and earth:

- The earth was not, you created it

- The light of day was not, you created it

- The morning light you had not [yet] made exist.

Its location apparently gave Ebla exposure to several religious cultures. Although Sumerian gods were also honored, the Canaanite god El has been found at the top of a list of deities worshiped there. Other well-known Semitic deities appearing at Ebla include Dagan, Ishtar, and Hadad, plus several Sumerian gods such as (Enki and Ninki (Ninlil), and the Hurrian deities (Ashtapi, Hebat, and Ishara). Some otherwise unknown gods are also mentioned, namely Kura and Nidakul.

Archaeologist Giovanni Pettinato has noted a change in the theophoric personal names in many of the tablets from "-el" to "-yah." For example "Mika’el" transforms into "Mikaya." This is considered by some to constitute an early use of the divine name Yah, a god who believed to have later emerged as the Hebrew deity Yahweh. Others have suggested that this shift indicates the popular acceptance of the Akkadian God Ea (Sumerian: Enki) introduced from the Sargonid Empire, which may have been transliterated into Eblaite as YH.[2]

Many Old Testament personal names that have not been found in other Near Eastern languages have similar forms in Eblaite, including a-da-mu/Adam, h’à-wa /Eve, Abarama/Abraham, Bilhah, Ishmael, Isûra-el, Esau, Mika-el/Michael, Mikaya/Michaiah, Saul, and David). Also mentioned in the Ebla tablets are many biblical locations: For example, Ashtaroth, Sinai, Jerusalem (Ye-ru-sa-lu-um), Hazor, Lachish, Gezer, Dor, Megiddo, Joppa, and so on.

Destruction and reemergence

Sargon of Akkad and his grandson Naram-sin, the conquerors of much of Mesopotamia, both claim to have destroyed Ebla. The exact date of destruction is the subject of continuing debate, but 2240 B.C.E. is a probable candidate.

Over the next several centuries, Ebla was able to regain some economic importance in the region, but never reached its former glory. It is possible the city had economic ties with the nearby city of Urshu, as is documented by economic texts from Drehem, a suburb of Nippur, and from findings in Kultepe/Kanesh.

Ebla's second apogee lasted from about 1850 to 1600 B.C.E. During this period the people of Ebla were apparently Amorites. Ebla is mentioned in texts from Alalakh around 1750 B.C.E.Ibbit-Lim was the first known king of Ebla during this time.

The city was destroyed again in the turbulent period of 1650–1600 B.C.E., by a Hittite king (Mursili I or Hattusili I). Ebla never recovered from its second destruction. It continued only as a small village until the seventh century C.E., then was deserted and forgotten until its archaeological rediscovery.

See also

- Sumerian Civilization

- Biblical archaeology

- Sargon I

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cornelius, Izak, and Louis C. Jonker. From Ebla to Stellenbosch: Syro-Palestinian Religions and the Hebrew Bible. Abhandlungen des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins, Bd. 37. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz in Kommission, 2008. ISBN 978-3447057769

- Gordon, Cyrus Herzl, and Gary Rendsburg. Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language. Winona Lake, Ind: Eisenbrauns, 2002. ISBN 978-1575060606

- Matthiae, Paolo. Ebla: An Empire Rediscovered. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1981. ISBN 978-0385129046

- Pettinato, Giovanni. The Archives of Ebla: An Empire Inscribed in Clay. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1981. ISBN 978-0385131520

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.