Difference between revisions of "Classical economics" - New World Encyclopedia

m (Robot: Remove claimed tag) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (83 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{Copyedited}} | |

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Economics]] | [[Category:Economics]] | ||

{{History of economic thought}} | {{History of economic thought}} | ||

| − | '''Classical economics''' is widely regarded as the first modern school of [[history of economic thought|economic thought]]. Its major developers include [[Adam Smith]], [[David Ricardo]], [[Thomas Malthus]] and [[John Stuart Mill]]. | + | '''Classical economics''' is widely regarded as the first modern school of [[history of economic thought|economic thought]]. The term "classical" refers to work done by a group of economists in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Its major developers include [[Adam Smith]], [[David Ricardo]], [[Thomas Malthus]] and [[John Stuart Mill]]. |

| + | Much of their work was developing theories about the way [[market]]s and market [[economy|economies]] work. Coming at a time when [[Mercantilism]] held sway, emphasizing the maximizing of exports and minimizing imports, classical economists promoted a radically different approach. They essentially regarded the economy as able to maintain its own equilibrium through market forces, and that government intervention in the form of artificial [[tariff]]s or other barriers that disrupted the free flow of [[good (economics)|good]]s and [[service (economics)|service]]s were harmful to the economy. | ||

| − | + | Classical economics was a major intellectual achievement. While new techniques of analysis were required to address new questions, giving rise to the [[mathematics|mathematical]] formulations of the [[neoclassical economics|neoclassicals]] and others, and advances in [[technology]] and changes in social awareness appear to have transformed the economic landscape, economic theory today still rests in many areas, monetary and trade theory to name but two, upon the foundations laid by classical economists. | |

| − | == | + | ==Foundations== |

| + | '''Classical economics''' refers to the school of economic thought that arose in [[Great Britain]] in the latter part of the eighteenth century. In the year 1776, [[David Hume]] died while [[Jacques Turgot]] and [[Marquis de Condorcet]] left their government posts. In that same year, though, the intellectual revolution they had contributed to, the [[Enlightenment]], began to bear its principal fruit. It was a year of grand treatises. [[Adam Smith]] published his ''Wealth of Nations,'' the Abbé de [[Condillac]] his ''Commerce et le Gouvernement,'' [[Jeremy Bentham]] his ''Fragments on Government,'' and [[Tom Paine]] his ''Common Sense.'' | ||

| − | + | It was Smith's work that has been seen as laying the foundation of economics as a separate academic discipline. The central messages of his ''Wealth of Nations'' (1776) were ''[[laissez-faire]]''—the virtues of specialization, [[free trade]] and [[competition (economics)|competition]], and so forth. Smith's vision of a free market economy, based on secure [[property]], [[Capital (economics) |capital]] accumulation, widening markets, and a [[division of labor]] contrasted with the [[mercantilism|mercantilist]] tendency to attempt to "regulate all evil human actions" (Smith 1776). | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Essentially this approach places total reliance on markets, and anything that prevent markets clearing properly should be done away with. The earlier belief that [[agriculture]] was the chief determinant of economic health was also rejected in favor of the development of [[manufacturing]], and the importance of labor productivity was stressed. The theories put forward by the classical economists still influence economics to this day. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | The classical economists strongly believed that the government should not intervene to try to correct this as it would only make things worse and so the only way to encourage growth was to allow free trade and free markets. Much of Adam Smith's early work was on this theme, and he introduced the notion of an "invisible hand" that guided economic activity and led to the optimum equilibrium. | ||

| + | Following Smith, in the struggle for succession as the voice of economic theorizing, three names emerged as strong contenders: | ||

*[[Jean-Baptiste Say]], | *[[Jean-Baptiste Say]], | ||

| − | + | *[[Robert Malthus]], and | |

| − | *[[Robert Malthus]] and | ||

| − | |||

*[[David Ricardo]]. | *[[David Ricardo]]. | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | These three had very different visions. Say (1803) wanted to take economic thought back towards the French-Italian demand-and-supply tradition. Malthus (1798, 1820) wanted to add a whole new emphasis, away from the obsessive intricacies of "value" and towards a more [[macroeconomics|macroeconomic]] (and "dynamic") perspective. As Smith's ''laissez-faire'' approach, including specialization, free trade, and so forth, did not anticipate the magnitude of the economic and social upheavals that the [[industrialization|industrial]] era was about to unleash, a new version, corrected, extended, and updated, was clearly needed. Ricardo (1817) wanted to do Smith all over again, but to do it properly this time. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Hence, out of these three, David Ricardo turned out to be the most successful and influential. With his 1817 treatise, Ricardo took economics to an unprecedented degree of theoretical sophistication. Ricardo's theory, the most clearly and consistently formalized of them all, became the "Classical system." | |

| − | + | Coming at the end of the classical tradition, [[John Stuart Mill]] parted company with the earlier classical economists on the inevitability of the distribution of [[income]] produced by the market system. Mill pointed to a distinct difference between the market's two roles: allocation of resources and distribution of income. The market might be efficient in allocating resources but not in distributing income, he wrote, making it necessary for society to intervene. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Adam Smith=== | |

| + | {{Main|Adam Smith}} | ||

| + | [[Image:AdamSmith.jpg|thumb|left|150 px|Adam Smith]] | ||

| + | Adam Smith was a Scottish political economist, lecturer, and essayist. His ''An Inquiry in to the Cause of the Wealth of Nations'' (1776) represents a highly critical commentary on [[mercantilism]], the prevailing economic system of Smith's day. Mercantilism emphasized the maximizing of exports and the minimizing of imports. In ''Wealth of Nations'' Smith argued that everyone benefits from the removal of tariffs and other barriers to trade. Because of supply and demand, production will increase as demand increases. This may lead to new employment opportunities for the workforce and to collateral industries emerging in response to new demands. For example, an increase in France's wine production would also lead to an increased demand for bottles, for barrels, for cork, and an increase in shipping, thus leading to a variety of new employment opportunities. | ||

| − | + | Adam Smith was convinced that the free market would stimulate development, improve living conditions, reduce social strife, and create an atmosphere that was conducive to peace and human cooperation. In his view, a balance had to exist between self interest and sympathy, with sympathy being the guiding moral imperative. Competition would emerge and serve as a check to profiteering and unfair pricing. Smith made compelling arguments for the free market and his economic and moral writings remain relevant today. ''Wealth of Nations'' serves as one of the most elegant explanations for the rapid economic growth experienced by the United States and other industrial powers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. | |

| + | ===Jean-Baptiste Say=== | ||

| + | {{Main|Jean-Baptiste Say}} | ||

| + | Jean-Baptiste Say (1767-1832) was a Frenchman, born in [[Lyon, France|Lyon]], who helped to popularize Adam Smith's work in France (Fusfeld 1994, 47). He had classically liberal views and argued in favor of [[competition]], [[free trade]], and lifting restraints on [[business]]. Say did not, however, agree with Smith's [[labor theory of value]] that the [[value (economics)|value]] of a commodity depends on the [[labor]] involved in its production, or "productive agency," arguing instead that value derives from its [[utility]], or capacity to satisfy the desires or needs of the consumer (Say 1803). | ||

| − | + | His most significant contribution is the thesis contained in his book, ''A Treatise on Political Economy'' (1803), that [[supply]] creates its own [[demand]]. Known as [[Say's Law]] of [[market]]s, this became orthodoxy in political economics until the [[Great Depression]]. Say argued that there could never be a general deficiency of demand or a general glut of commodities in the whole economy. Thus he supported the ''[[laissez-faire]]'' position of Adam Smith, stating that overproduction in one market will naturally return to balance without government interference as the producer will either adjust production to different items or adjust [[price]]s until the goods sell. He argued that production is not a question of supply, but an indication of producers demanding goods. Production ''is'' demand, so it is impossible for production to outrun demand, or for there to be a "general glut" of supply. At most, there will be different economic sectors whose demands are not fulfilled. But over time supplies will shift, businesses will retool for different production, and the market will correct itself. An example of a "general glut" could be [[unemployment]], in other words, too great a supply of workers, and too few jobs. Say's Law advocates would suggest that this necessarily means there is an excess demand for other products that will correct itself. This remained a foundation of economic theory until the 1930s. However one political economist, Malthus, a contemporary of Say, was unconvinced. | |

| − | + | ===Thomas Robert Malthus=== | |

| + | {{Main|Thomas Robert Malthus}} | ||

| + | [[Image:Thomas Malthus.jpg|thumb|150 px|right|Malthus cautioned law makers on the effects of poverty reduction policies]] | ||

| + | Thomas Robert Malthus (1766-1834) believed in strict government abstention from social ills. In his work, ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'' (1798), he argued that intervention was impossible because of two factors. "Food is necessary to the existence of man," wrote Malthus. "The passion between the sexes is necessary and will remain nearly in its present state," he added, meaning that the "power of the population is infinitely greater than the power in the Earth to produce subsistence for man." Nevertheless growth in population is checked by "misery and vice." Any increase in wages for the masses would cause only a temporary growth in population, which given the constraints in the supply of the Earth's produce would lead to misery, vice and a corresponding readjustment to the original population. However more labor could mean more economic growth, either one of which was able to be produced by an accumulation of capital. | ||

| − | + | Malthus devoted the last chapter of his ''Principles of Political Economy'' (1820) to rebutting Say's law, and argued that the economy could stagnate with a lack of "effectual demand." In other words, wages less than the total costs of production cannot purchase the total output of industry and this would cause prices to fall. Price falls cause incentives to invest, and the spiral could continue indefinitely. | |

| + | ===David Ricardo=== | ||

| + | {{Main|David Ricardo}} | ||

| + | [[Image:David ricardo.jpg|thumb|Ricardo is renowned for his law of [[comparative advantage]]]] | ||

| + | David Ricardo (1772-1823) was born in London, and by the age of 26 had become a wealthy stock market trader. He bought himself a constituency seat in Ireland to gain a platform in the [[British House of Commons|House of Commons]] in the [[Parliament of the United Kingdom]]. Ricardo's best known work is his ''Principles of Political Economy and Taxation'' (1817, 1821), which contains his critique of barriers to international trade. | ||

| − | + | Economics for Ricardo was all about the relationship between the three "factors of production" - [[land]], [[labor]], and [[capital]]. He demonstrated mathematically that the gains from trade would outweigh the perceived advantages of protectionist policy. His theory of [[comparative advantage]] suggested that even if one country is inferior at producing all of its goods than another, it may still benefit from opening its borders since the inflow of goods produced more cheaply than at home produces a gain for domestic consumers. For example, in two days an average worker in England produces a bushel of wheat and in one day a [[yard]] of cloth, while the average French worker can do either in just a day. If England exchanges the wheat it produces (one day's production) for French cloth (while English cloth takes two days) then both sides can strike a bargain between the margin that is mutually beneficial. England by selling its wheat can get its cloth in a day, rather than two days, and France can get an extra bushel of wheat for selling its more efficiently produced cloth. This would lead to a shift in prices so that eventually England would be producing the goods in which its comparative advantages were the highest. His thinking was instrumental in the repeal of the [[Corn Laws]]. | |

| − | |||

| + | ===John Stuart Mill=== | ||

| + | {{Main|John Stuart Mill}} | ||

| + | [[Image:John-stuart-mill-sized.jpg|right|thumb|Mill, brought up on the philosophy of Jeremy Bentham, wrote the most authoritative economics text of the time]] | ||

| + | [[John Stuart Mill]] (1806-1873) was the dominant figure of political economic thought of his time, as well as being a [[Member of Parliament]] for the seat of [[Westminster]], and a leading political philosopher. [[Jeremy Bentham]] was a close mentor and family friend, and Mill was heavily influenced by [[David Ricardo]]. Mill's textbook, ''Principles of Political Economy,'' first published in 1848 was essentially a summary of the economic wisdom of the mid-nineteenth century (Pressman 2006, 44). It was used as the standard texts by most universities well into the beginning of the twentieth century. | ||

| − | + | Mill tried to find a middle ground between Adam Smith's view of ever expanding opportunities for trade and technological innovation and Thomas Malthus' view of the inherent limits of population. In his fourth book Mill set out a number of possible future outcomes, rather than predicting one in particular. The first followed the Malthusian line that population grew quicker than supplies, leading to falling wages and rising profits. The second, per Smith, said if capital accumulated faster than population grew then [[real wage]]s would rise. Third, echoing David Ricardo, should capital accumulate and population increase at the same rate, yet technology stay stable, there would be no change in real wages because supply and demand for labor would be the same. However growing populations would require more land use, increasing food production costs and therefore decreasing profits. The fourth alternative was that technology advanced faster than population and capital stock increased. The result would be a prospering economy. Mill felt the third scenario most likely, as he assumed technology advances would have to end at some point (Pressman 2006, 45). But on the prospect of continuing [[economic growth]], Mill was more ambivalent: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>I confess I am not charmed with the ideal of life held out by those who think that the normal state of human beings is that of struggling to get on; that the trampling, crushing, elbowing, and treading on each other's heels, which form the existing type of social life, are the most desirable lot of human kind, or anything but the disagreeable symptoms of one of the phases of industrial progress (Mill 1871).</blockquote> | |

| − | + | Mill is also credited with being the first person to speak of supply and demand as a relationship rather than mere quantities of goods on markets (Stigler 1965, 1-15), the concept of [[opportunity cost]], and the rejection of the [[wage fund doctrine]] (Pressman 2006, 46). | |

| − | + | ==Theory== | |

| + | Classical theories revolved mainly around the role of [[market]]s in the [[economy]]. If markets worked freely and nothing prevented their rapid clearing then the economy would prosper. Any imperfections in the market that prevented this process should be dealt with by [[government]]. On the other hand, government interventions that inhibit the free flow of goods and services are detrimental. The main roles of government are therefore to ensure the free workings of markets using "supply-side policies" and to ensure a balanced [[budget]]. | ||

| + | The main theories used to justify this view were the "Free market theory," "Say's Law," and the "Quantity theory of money." | ||

| − | This | + | ===Free market theory=== |

| + | Classical economists assumed that if the economy was left to itself, then it would tend to full employment equilibrium. This would happen if the [[labor]] market worked properly. If there was any [[unemployment]], then the following would happen: | ||

| − | + | :'''UNEMPLOYMENT——>INCREASED DEMAND FOR LABOR——>FALL IN WAGES——>EQUILIBRIUM RESTORED''' | |

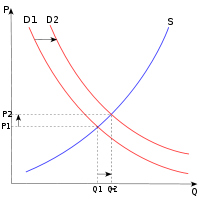

| + | As the "Demand curve" illustrates, it is argued that there is an inverse relationship between the [[wage]] rate (or [[price]] of labor) , depicted on the vertical (price) axis P, and the quantity of labor demanded, which is depicted (as quantity of any other goods) on the horizontal (quantity) axis Q. There is also a “supply” (of labor) curve S in this Diagram. | ||

| + | [[Image:Supply-and-demand.svg|thumb|right|200 px|An example of a "Demand curve" following the classical economics view. The [[demand]] curve is defined as the [[graph]] depicting the relationship between the [[price]] of a certain [[commodity]], and the amount of it that consumers are willing and able to purchase at that given price.]] | ||

| + | This negative relationship between the wage and the quantity of labor demanded is the result of two effects: | ||

| + | ;Substitution effect | ||

| − | + | In a practical economic example, let the WAGE (P) mean PRICE per combination of Products 1 and 2 (for example, pizza and Italian bread) while QUANTITY of labor (Q) is the total output of Product 1 and Product 2. Let us now assume that the price of Product 2 (Italian bread) that uses the same technology, ingredients, know-how, buildings and so forth decreases, which reduces the opportunity cost of making pizza (Product 1). | |

| − | + | Hence, some bread makers move into the pizza business to substitute for the lag in the overall demand for pizza. At this point, the original equilibrium point—E1 = intersection of [P1, Q1]—with constant wages on the line [P1, E1] moves to the right to intersect with D2, which is the expected optimum output of pizza. Hence, for some time, before the equilibrium is restored at [P2, D2], the quantity of labor demand is reduced, or is, at the best, constant ( apparently content with the lower wages on the line [P1, E1]) while, at all times, the labor supply is constant as seen in equilibria [P1, D1] and [P2, D2]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Eventually, an equilibrium occurs in a labor market at the combination of wages and employment at which market demand and supply intersect (as illustrated in the diagram). | ||

| − | If the wage rate is above the equilibrium, the quantity of labor supplied exceeds the quantity demanded and a surplus occurs. In this case, the existence of unemployed workers will be expected to result in downward pressure on the wage rate until an equilibrium is restored. | + | *If the wage rate is above the equilibrium, the quantity of labor supplied exceeds the quantity demanded and a surplus occurs. In this case, the existence of unemployed workers will be expected to result in downward pressure on the wage rate until an equilibrium is restored. |

| − | |||

| − | If the wage rate is below the equilibrium, a labor shortage will occur. Competition among firms for workers is expected to result in increases in the wage until an equilibrium occurs. | + | *If the wage rate is below the equilibrium, a labor shortage will occur. Competition among firms for workers is expected to result in increases in the wage until an equilibrium occurs. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ;Scale effect | ||

The scale effect resulting from a wage increase is a bit more complex. As the wage rate rises, the scale effect involves the following chain of effects: | The scale effect resulting from a wage increase is a bit more complex. As the wage rate rises, the scale effect involves the following chain of effects: | ||

| + | # higher wages result in higher average and marginal costs of production, | ||

| + | # higher average and marginal and average costs result in an increase in the equilibrium price of the product, | ||

| + | # as the price of the product rises, the equilibrium quantity of the product demanded declines (a reduction in the "scale" of production), and | ||

| + | # the reduction in output results in a reduction in the quantity of all inputs used to produce this product (including this category of labor). | ||

| + | Hence, classical economists were of the view that the economy is self-adjusting. In fact, in their view, because the economy tends to full-employment, there is no need for government to actively intervene. In fact, intervention may simply be destabilizing and inflationary. The key to long-term stable economic growth is therefore to: | ||

| + | *ensure [[free market]]s with no imperfections (through supply-side policies); and | ||

| + | *control the growth of the [[money supply]] to ensure low [[inflation (economics)|inflation]]. | ||

| − | + | The effect of supply-side policies can be seen in the above diagram when we assume only one price level, say P1, and we increase the level of output from Q1 to Q2, while the price level P1 remains stable. Supply-side policies as we have said are ones that reduce market imperfections. They may include: | |

| − | + | *Improving education and training to make the work-force more occupationally mobile, | |

| − | * | + | *reducing the level of benefits to increase the incentive for people to work, |

| − | + | *reducing [[taxation]] to encourage enterprise and encourage hard work, | |

| − | *( | + | *policies to make people more geographically mobile (ending [[rent]] controls, simplifying house buying, and so forth), |

| − | + | *reducing the power of [[trade union]]s to allow wages to be more flexible, | |

| − | * | + | *removing any capital controls, and |

| − | + | *removing unnecessary regulations. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | " | + | ===Say’s Law=== |

| + | [[Jean-Baptiste Say]] was adamant in his opposition to government intervention into the economy. Most succinctly stated, he declared that self-interest and the search for [[profit]]s will push [[entrepreneur]]s toward satisfying consumer demand: "the nature of the products is always regulated by the wants of society," therefore "legislative interference is superfluous altogether" (Say 1803, 144). | ||

| + | It was in his ''Treatise'' (Say 1803) that Say outlined his famous law: [[Say's Law]] claims that total demand in an economy cannot exceed or fall below total supply in that economy or, as [[James Mill]] restated it, "production of commodities creates, and is the one and universal cause which creates a market for the commodities produced." In Say's language, "products are paid for with products" (1803, 153) or "a glut can take place only when there are too many means of production applied to one kind of product and not enough to another" (1803, 178-179). | ||

| + | Say argued against claims that business was suffering because people did not have enough money and more money should be printed. Say argued that the power to purchase could be increased only by more production. | ||

| − | + | It is important to note that Say himself never used many of the later short definitions of Say's Law, including [[John Maynard Keynes]]' somewhat inaccurate version, "supply creates its own demand." Say's Law actually developed due to the work of many of his contemporaries and those who came after him. The work of James Mill, [[David Ricardo]], [[John Stuart Mill]], and others developed it into what is sometimes called the "law of markets" which was the framework of [[macroeconomics]] from the mid-1800s until the 1930s. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Quantity theory of money=== | ===Quantity theory of money=== | ||

| − | + | Classical economists ascribe one other important role to the government: to control [[money supply|monetary]] growth. In this way, as predicted by the [[Quantity theory of money]] (QTM), they would be able to maintain low [[inflation (economics)|inflation]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The Quantity | + | The Quantity theory of money states that there is a direct relationship between the quantity of [[money]] in an [[economy]] and the level of [[price]]s of [[good (economics)|good]]s and [[service (economics)|service]]s sold. According to QTM, if the amount of money in an economy doubles, price levels also double, causing inflation (the percentage rate at which the level of prices is rising in an economy). The consumer therefore pays twice as much for the same amount of the good or service. |

| − | + | This idea was first promoted in the seventeenth century by [[John Locke]] and [[David Hume]]. The original proposition was to refute [[Mercantilism]]'s equation of money with [[wealth]], and based on shrewd observation of the impact of the influx of [[precious metal]]s from the [[New World]]. With the advent of [[fiat money]] (bank notes and other non-metallic forms) the possibility of hoarding money as wealth, which reduced the quantity effect, was lost. [[John Stuart Mill]] noted this in his development of the QTM, making clear that the medium-of-exchange function of money is essential to the effect. His work also laid the foundation for this theory to play a significant role in twentieth century economics, long after new theories of economics had replaced the classical tradition. | |

| + | ==Impact in the nineteenth century== | ||

| − | + | === The rationality principle=== | |

| + | Ricardian notions such as comparative advantage in international trade rest on the idea that people are rational (Ricardo, 1951). In other words, it is implied that traders produce [[good (economics)|goods]] that they can trade, and they sell to those who offer the highest price: | ||

| + | <blockquote>If one of the wine sellers were offering only four quarts for a bushel, the owner of the wheat will not give it to this wine seller if he knows that another will give him six or eight quarts for the same bushel (Lagueux 1997)</blockquote> | ||

| + | This type of thinking is neatly illustrated by the saga of the British Corn Laws, import [[tariff]]s designed to protect British corn against competition from cheaper foreign imports, and their eventual repealing thirty years later. The [[Corn Laws]] were adopted by the [[Tories (political faction)|Tories]] who represented the landed class and greatly benefited from agricultural protections, and were designed to keep prices high after the [[Napoleonic Wars]]. They feared that a drop in prices due to foreign imports would harm them financially. The [[Whig (British political faction)|Whigs]], on the other hand, were [[business]] owners. Following [[David Ricardo]]'s economic views they believed a decrease in the price of grain would allow them to lower wages and through that increase their profits. | ||

| − | + | The [[Corn Laws]] had been passed in 1815, setting a fluctuating system of [[tariff]]s to stabilize the price of [[wheat]] in the domestic market. Ricardo argued that raising tariffs, despite being intended to benefit the incomes of farmers, would merely produce a rise in the prices of [[rent]]s that went into the pockets of landowners. Furthermore, extra labor would be employed leading to an increase in the cost of wages across the board, and therefore reducing exports and profits coming from overseas business. In 1841, Sir [[Robert Peel]] became Conservative Prime Minister and [[Richard Cobden]], a leading free trader, was elected for the first time. With Cobden's support Peel was persuaded to the position of the classical economists, and in 1846, the Corn Laws were repealed. | |

| − | + | ===Exploitation theory=== | |

| + | Exploitation theory was developed by [[Karl Marx]]. It states that [[profit]] is the result of the [[exploitation]] of wage earners by their employers. There are three aspects of classical economics which contribute to this exploitation theory. The two best known are: | ||

| + | *The [[labor theory of value]] and | ||

| + | *The [[iron law of wages]]. | ||

| + | Somewhat less prominent, but no less important, is the conceptual framework within which the exploitation theory is advanced. This framework is the belief that: | ||

| + | *Wages are the original and primary form of income, from which profits and all other non-wage incomes emerge as a deduction with the coming of capitalism and businessmen and capitalists. | ||

| − | '' | + | It is on the basis of these beliefs that [[Adam Smith]] opened his chapter on wages in ''The Wealth of Nations'' with the words: |

| + | <blockquote>The produce of labour constitutes the natural recompense or wages of labour. In that original state of things, which precedes both the appropriation of land and the accumulation of stock, the whole produce of labour belongs to the labourer. He has neither landlord nor master to share with him (Smith 1776).</blockquote> | ||

| − | + | In these, and other passages, Smith clearly advances the primacy of wages doctrine. That is, the doctrine that in a pre-capitalist economy, in the "early and rude state of society," workers simply produce and sell commodities and do not buy in order to sell; the income the workers receive are wages. | |

| + | "Wages are the original income,” according to Smith. "All income in the pre-capitalist society is supposed to be wages, and no income is supposed to be profit … because workers are the only recipients of income" (Smith 1776). | ||

| − | + | At the same time, Smith advances the corollary doctrine that "profit emerges only with the coming of capitalism and is a deduction from what is naturally and, by implication, rightfully wages" (Smith 1776). | |

| + | Within this framework, Marx applied the labor theory of value and the iron law of wages, and arrives at the exploitation theory. | ||

| − | + | Resting on the [[labor theory of value]], which claims that [[value (economics)|value]] is intrinsic in a product according to the amount of [[labor]] that has been spent on producing the product, Marx stated that the value of a product is created by the workers who made that product and reflected in its finished [[price]]. Thus, workers are the fundamental creative source of new value. The income from this finished price is then divided between labor (wages), capital ([[profit]]), and expenses on raw materials. Property relations affording the right control of the workplace to capitalists are the devices by which the "[[surplus value]]" created by workers is appropriated by the capitalists. The wages received by workers do not reflect the full value of their work, because some of that value is taken by the employer in the form of profit. Therefore, "making a profit" essentially means taking away from the workers some of the value that results from their labor. This is what is known as capitalist exploitation. | |

| − | + | ==Continuing contributions== | |

| − | + | Despite being overtaken by [[neoclassical economics]] in the latter part of the nineteenth century, many aspects of classical economic theory continue to inform and impact the world. Following are some examples. | |

| − | + | ===Quantity theory of money=== | |

| − | + | This theory, originating early and developed by [[John Stuart Mill]], was formalized in the twentieth century by [[Irving Fisher]]. It has played a continuing role in economics, featuring in the work of [[Milton Friedman]] (1956). In its simplest form (the Fisher Equation) the theory is expressed as | |

| + | :''' MV = PT''' | ||

| + | where each variable denotes the following: | ||

| + | :'''M = Money Supply''' | ||

| + | :'''V = Velocity of Circulation''' (the number of times money changes hands) | ||

| + | :'''P = Average Price Level''' | ||

| + | :'''T = Volume of Transactions of Goods and Services'''. | ||

| + | It is built on the principle of equation of exchange: | ||

| + | :'''Amount of Money x Velocity of Circulation = Total Spending''' | ||

| − | + | Another way to understand this theory is to recognize that money is like any other commodity. An increase in [[money supply]] causes prices to rise ([[inflation (economics)|inflation]]) as they compensate for the decrease in money’s marginal value. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Policies | + | Policies to control the quantity of money in circulation include: |

| − | |||

| − | |||

*Open-market operations. | *Open-market operations. | ||

| − | |||

*Funding. | *Funding. | ||

| − | |||

*Monetary-base control. | *Monetary-base control. | ||

| − | |||

*Interest rate control. | *Interest rate control. | ||

| − | + | ===Critique of exploitation theory=== | |

| − | + | Despite the support which it seems to be giving to the exploitation theory, given that [[Marx]] used classical ideas such as the labor theory of value to develop it, classical economics provides the basis for turning the exploitation theory upside down. On the basis of [[Ricardo]]'s concept of [[profit]] and [[J. S. Mill]]'s proposition that "demand for commodities is not demand for labor," it is possible to show how profits, not [[wages]], must be regarded as the original and primary form of income, from which other incomes emerge as a deduction. | |

| − | |||

| − | == | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Classical theory also reveals the labor of businessmen and capitalists has more fundamental responsibility for the production of products than the labor of wage earners, with the result that "labor's right to the whole produce" should mean the right of businessmen and capitalists to the sales receipts—a right which is accepted in the normal operations of a capitalist economy. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | " | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The classical doctrines of [[supply and demand]], the wage fund, the distinction between value and [[wealth|riches]], and the labor theory of value─modified along lines suggested by Ricardo and J. S. Mill and incorporating the advances in price theory made by [[Böhm-Bawerk]]─make possible an explanation of real wages. Böhm-Bawerk applied the discounting approach, criticizing exploitation theory (Bohm-Bawerk 1959). | |

| − | |||

| − | + | For classical economics implies that it is false to claim that wages are the original form of income and that profits are a deduction from them. This becomes apparent, as soon as we define our terms along classical lines: | |

| + | *'''Profit''' is the excess of receipts from the sale of products over the money costs of producing them—over, it must be repeated, the money costs of producing them. | ||

| + | *A '''capitalist''' is one who buys in order subsequently to sell for a profit. | ||

| + | *'''Wages''' are money paid in exchange for the performance of labor—not for the products of labor, but for the performance of labor itself. | ||

| − | + | On the basis of these definitions it follows that, if there are merely workers producing and selling their products, the money which they receive in the sale of their products is not wages. "Demand for commodities," to quote John Stuart Mill, "is not demand for labour. ... in buying commodities, one does not pay wages, and in selling commodities, one does not receive wages” (Mill 1976). | |

| − | + | [[F. A. Hayek]] also contributed to this discourse, with such statements as: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>The actual history of the connection between capitalism and the rise of the proletariat is almost the exact opposite of that which these theories of the expropriation of the masses suggest.<br/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | The proletariat which capitalism can be said to have 'created' was thus not a proportion of the population which would have existed without it and which it degraded to a lower level; it was an additional population which was enabled to grow up by the new opportunities for employment which capitalism provided. (Hayek, 1954)</blockquote> | ||

| + | Finally, on the doctrine of “iron law of wages,“ the following can be said. The rising productivity of labor and correspondingly falling product prices that the businessmen and capitalists achieve take place in this context of wage rates that are determined by the independent supply of and demand for labor. Thus, as product prices fall, wage rates do not fall, and, therefore, real wages rise. (If, the quantity of money and volume of spending in the economic system remaining the same, there is a growing supply of labor while the productivity of labor rises, money wage rates fall, but prices fall by more.) Of course, to the extent that the quantity of money increases while the productivity of labor rises, the demand for labor and products both increase. | ||

| + | As a result, the rise in real wages may be accompanied by rising money wage rates and by constant or even rising product prices. But the relationship between wages and prices will reflect the change in the productivity of labor, for that reduces product prices relative to wages, while the increase in the quantity of money operates to affect both of them more or less equally (Reisman 1985). | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | *Böhm-Bawerk, E. von. | + | *Böhm-Bawerk, E. von. 1959. ''Capital and Interest.'' South Holland, IL: Libertarian Press. |

| − | *Fisher, | + | *Fisher, Irving. [1911] 2006. ''The Purchasing Power of Money: Its Determination and Relation to Credit, Interest, and Crises.'' Cosimo Classics. ISBN 1596056134 |

| − | *Friedman, | + | *Friedman, Milton. 1956. The Quantity Theory of Money: A restatement. ''Studies in Quantity Theory.'' Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226264068 |

| − | *Hayek, F. A. | + | *Fusfeld, Daniel R. [1994]. ''The Age of the Economist,'' 9th ed. Addison Wesley, 2001. ISBN 0321088123 (general survey of theory and predictions) |

| − | *Hayek, F. A. | + | *Hayek, F. A. [1944] 2001. ''The Road to Serfdom.'' Routledge. ISBN 0415255430 |

| − | *Hollander, J. | + | *Hayek, F. A. (ed.). [1954] 2003. ''Capitalism and the Historians.'' Routledge. ISBN 0415313287 |

| − | *Laidler, D. | + | *Hollander, J. 1910. The Development of the Theory of Money From Adam Smith to David Ricardo. ''Quarterly J. of Economics''. |

| − | University Press,'' | + | *Lagueux, M. 1997. [http://www.philo.umontreal.ca/textes/Lagueux_Rationality_princip.pdf The Rationality Principle and Classical Economics]. ''Congrès de History of Economics Society tenu à Charleston''. University of Montreal. Retrieved September 24, 2008. |

| − | *Mill, John | + | *Laidler, D. 1991. ''The Golden Age of the Quantity Theory,'' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691042950 |

| − | *Mises, Ludwig von | + | *Malthus, T. R. [1798] 1993. ''An Essay on the Principle of Population,'' Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192830961 |

| − | *Newcomb, | + | *Malthus, T. R. [1820] 2008. ''Principles of Political Economy,'' Cambridge University Press. Volume 1: ISBN 0521075912; Volume 2: ISBN 0521075939 |

| − | *Reisman, | + | *Mill, John Stuart. [1848 and 1871] 1976. ''Principles of Political Economy.'' Fairfield, NJ: Augustus M. Kelley. |

| − | *Reisman, | + | *Mises, Ludwig von. 1966. ''Human Action,'' 3rd ed. Chicago, IL: Henry Regnery Company. ISBN 0930073185 |

| − | *Ricardo, | + | *Newcomb, Simon. 1885. ''Principles of Political Economy.'' New York, NY: Harper. ISBN 0781246210, online [http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&id=br2e6DJZoEQC&dq=Principles+of+Political+Economy+newcomb&printsec=frontcover&source=web&ots=SKpPusrBl9&sig=T8qxdbBjBwfW4B4Igc4vsGlVDXQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result]''googlebooks.com''. Retrieved October 9, 2008. |

| − | *Say, Jean-Baptiste | + | *Ormazabal, Kepa M. 2005. “Neo-Classical Economics Is Not ‘Neo’, But ‘Anti’-Classical,” ''Post-Autistic Economics Review'' 30(5). |

| − | *Smith, Adam | + | *Pressman, Steven. 2006. ''Fifty Major Economists.'' Routledge. ISBN 0415366496 |

| − | + | *Reisman, George. 1985. [http://mises.org/story/1729 Classical Economics vs. The Exploitation Theory] ''The Political Economy of Freedom Essays in Honor of F. A. Hayek''. München and Wien: ''Philosophia Verlag''. Retrieved August 27, 2008. | |

| + | *Reisman, George. 1996. ''Capitalism: A Treatise on Economics.'' Ottawa, IL: Jameson Books. ISBN 0915463733 | ||

| + | *Ricardo, D. [1817] 2004. ''Principles of Political Economy and Taxation.'' reprint Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0486434613 | ||

| + | *Ricardo, David. 1951. On the Protectionism of Agriculture. ''The Works and Correspondence of David Ricardo.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. | ||

| + | *Say, Jean-Baptiste. [1803] 1971. ''A Treatise on Political Economy: or the Production, Distribution and Consumption of Wealth,'' (translated by C. R. Prinsep and Clement C. Biddle). New York, NY: Augustus M. Kelley. 4th ed, by Michigan Historical Reprint Series, 2005. ISBN 142555492X | ||

| + | *Smith, Adam. [1776] 1998. ''The Wealth of Nations.'' Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192835467 | ||

| + | *Stigler, George J. 1965. "The Nature and Role of Originality in Scientific Progress." in ''Essays in the History of Economics.'' Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226774279 | ||

| − | {{Credits|Classical_economics|109613401|}} | + | {{Classical economists}} |

| + | {{Credits|Classical_economics|109613401|History_of_economic_thought|236134698}} | ||

Latest revision as of 21:39, 5 March 2020

| Schools of economics |

| Pre-modern |

|---|

| Early Modern |

| Modern |

|

Classical Economics |

| Twentieth-century |

|

Institutional economics · Stockholm school |

Classical economics is widely regarded as the first modern school of economic thought. The term "classical" refers to work done by a group of economists in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Its major developers include Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Thomas Malthus and John Stuart Mill.

Much of their work was developing theories about the way markets and market economies work. Coming at a time when Mercantilism held sway, emphasizing the maximizing of exports and minimizing imports, classical economists promoted a radically different approach. They essentially regarded the economy as able to maintain its own equilibrium through market forces, and that government intervention in the form of artificial tariffs or other barriers that disrupted the free flow of goods and services were harmful to the economy.

Classical economics was a major intellectual achievement. While new techniques of analysis were required to address new questions, giving rise to the mathematical formulations of the neoclassicals and others, and advances in technology and changes in social awareness appear to have transformed the economic landscape, economic theory today still rests in many areas, monetary and trade theory to name but two, upon the foundations laid by classical economists.

Foundations

Classical economics refers to the school of economic thought that arose in Great Britain in the latter part of the eighteenth century. In the year 1776, David Hume died while Jacques Turgot and Marquis de Condorcet left their government posts. In that same year, though, the intellectual revolution they had contributed to, the Enlightenment, began to bear its principal fruit. It was a year of grand treatises. Adam Smith published his Wealth of Nations, the Abbé de Condillac his Commerce et le Gouvernement, Jeremy Bentham his Fragments on Government, and Tom Paine his Common Sense.

It was Smith's work that has been seen as laying the foundation of economics as a separate academic discipline. The central messages of his Wealth of Nations (1776) were laissez-faire—the virtues of specialization, free trade and competition, and so forth. Smith's vision of a free market economy, based on secure property, capital accumulation, widening markets, and a division of labor contrasted with the mercantilist tendency to attempt to "regulate all evil human actions" (Smith 1776).

Essentially this approach places total reliance on markets, and anything that prevent markets clearing properly should be done away with. The earlier belief that agriculture was the chief determinant of economic health was also rejected in favor of the development of manufacturing, and the importance of labor productivity was stressed. The theories put forward by the classical economists still influence economics to this day.

The classical economists strongly believed that the government should not intervene to try to correct this as it would only make things worse and so the only way to encourage growth was to allow free trade and free markets. Much of Adam Smith's early work was on this theme, and he introduced the notion of an "invisible hand" that guided economic activity and led to the optimum equilibrium.

Following Smith, in the struggle for succession as the voice of economic theorizing, three names emerged as strong contenders:

These three had very different visions. Say (1803) wanted to take economic thought back towards the French-Italian demand-and-supply tradition. Malthus (1798, 1820) wanted to add a whole new emphasis, away from the obsessive intricacies of "value" and towards a more macroeconomic (and "dynamic") perspective. As Smith's laissez-faire approach, including specialization, free trade, and so forth, did not anticipate the magnitude of the economic and social upheavals that the industrial era was about to unleash, a new version, corrected, extended, and updated, was clearly needed. Ricardo (1817) wanted to do Smith all over again, but to do it properly this time.

Hence, out of these three, David Ricardo turned out to be the most successful and influential. With his 1817 treatise, Ricardo took economics to an unprecedented degree of theoretical sophistication. Ricardo's theory, the most clearly and consistently formalized of them all, became the "Classical system."

Coming at the end of the classical tradition, John Stuart Mill parted company with the earlier classical economists on the inevitability of the distribution of income produced by the market system. Mill pointed to a distinct difference between the market's two roles: allocation of resources and distribution of income. The market might be efficient in allocating resources but not in distributing income, he wrote, making it necessary for society to intervene.

Adam Smith

Adam Smith was a Scottish political economist, lecturer, and essayist. His An Inquiry in to the Cause of the Wealth of Nations (1776) represents a highly critical commentary on mercantilism, the prevailing economic system of Smith's day. Mercantilism emphasized the maximizing of exports and the minimizing of imports. In Wealth of Nations Smith argued that everyone benefits from the removal of tariffs and other barriers to trade. Because of supply and demand, production will increase as demand increases. This may lead to new employment opportunities for the workforce and to collateral industries emerging in response to new demands. For example, an increase in France's wine production would also lead to an increased demand for bottles, for barrels, for cork, and an increase in shipping, thus leading to a variety of new employment opportunities.

Adam Smith was convinced that the free market would stimulate development, improve living conditions, reduce social strife, and create an atmosphere that was conducive to peace and human cooperation. In his view, a balance had to exist between self interest and sympathy, with sympathy being the guiding moral imperative. Competition would emerge and serve as a check to profiteering and unfair pricing. Smith made compelling arguments for the free market and his economic and moral writings remain relevant today. Wealth of Nations serves as one of the most elegant explanations for the rapid economic growth experienced by the United States and other industrial powers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Jean-Baptiste Say

Jean-Baptiste Say (1767-1832) was a Frenchman, born in Lyon, who helped to popularize Adam Smith's work in France (Fusfeld 1994, 47). He had classically liberal views and argued in favor of competition, free trade, and lifting restraints on business. Say did not, however, agree with Smith's labor theory of value that the value of a commodity depends on the labor involved in its production, or "productive agency," arguing instead that value derives from its utility, or capacity to satisfy the desires or needs of the consumer (Say 1803).

His most significant contribution is the thesis contained in his book, A Treatise on Political Economy (1803), that supply creates its own demand. Known as Say's Law of markets, this became orthodoxy in political economics until the Great Depression. Say argued that there could never be a general deficiency of demand or a general glut of commodities in the whole economy. Thus he supported the laissez-faire position of Adam Smith, stating that overproduction in one market will naturally return to balance without government interference as the producer will either adjust production to different items or adjust prices until the goods sell. He argued that production is not a question of supply, but an indication of producers demanding goods. Production is demand, so it is impossible for production to outrun demand, or for there to be a "general glut" of supply. At most, there will be different economic sectors whose demands are not fulfilled. But over time supplies will shift, businesses will retool for different production, and the market will correct itself. An example of a "general glut" could be unemployment, in other words, too great a supply of workers, and too few jobs. Say's Law advocates would suggest that this necessarily means there is an excess demand for other products that will correct itself. This remained a foundation of economic theory until the 1930s. However one political economist, Malthus, a contemporary of Say, was unconvinced.

Thomas Robert Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (1766-1834) believed in strict government abstention from social ills. In his work, An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798), he argued that intervention was impossible because of two factors. "Food is necessary to the existence of man," wrote Malthus. "The passion between the sexes is necessary and will remain nearly in its present state," he added, meaning that the "power of the population is infinitely greater than the power in the Earth to produce subsistence for man." Nevertheless growth in population is checked by "misery and vice." Any increase in wages for the masses would cause only a temporary growth in population, which given the constraints in the supply of the Earth's produce would lead to misery, vice and a corresponding readjustment to the original population. However more labor could mean more economic growth, either one of which was able to be produced by an accumulation of capital.

Malthus devoted the last chapter of his Principles of Political Economy (1820) to rebutting Say's law, and argued that the economy could stagnate with a lack of "effectual demand." In other words, wages less than the total costs of production cannot purchase the total output of industry and this would cause prices to fall. Price falls cause incentives to invest, and the spiral could continue indefinitely.

David Ricardo

David Ricardo (1772-1823) was born in London, and by the age of 26 had become a wealthy stock market trader. He bought himself a constituency seat in Ireland to gain a platform in the House of Commons in the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Ricardo's best known work is his Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817, 1821), which contains his critique of barriers to international trade.

Economics for Ricardo was all about the relationship between the three "factors of production" - land, labor, and capital. He demonstrated mathematically that the gains from trade would outweigh the perceived advantages of protectionist policy. His theory of comparative advantage suggested that even if one country is inferior at producing all of its goods than another, it may still benefit from opening its borders since the inflow of goods produced more cheaply than at home produces a gain for domestic consumers. For example, in two days an average worker in England produces a bushel of wheat and in one day a yard of cloth, while the average French worker can do either in just a day. If England exchanges the wheat it produces (one day's production) for French cloth (while English cloth takes two days) then both sides can strike a bargain between the margin that is mutually beneficial. England by selling its wheat can get its cloth in a day, rather than two days, and France can get an extra bushel of wheat for selling its more efficiently produced cloth. This would lead to a shift in prices so that eventually England would be producing the goods in which its comparative advantages were the highest. His thinking was instrumental in the repeal of the Corn Laws.

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) was the dominant figure of political economic thought of his time, as well as being a Member of Parliament for the seat of Westminster, and a leading political philosopher. Jeremy Bentham was a close mentor and family friend, and Mill was heavily influenced by David Ricardo. Mill's textbook, Principles of Political Economy, first published in 1848 was essentially a summary of the economic wisdom of the mid-nineteenth century (Pressman 2006, 44). It was used as the standard texts by most universities well into the beginning of the twentieth century.

Mill tried to find a middle ground between Adam Smith's view of ever expanding opportunities for trade and technological innovation and Thomas Malthus' view of the inherent limits of population. In his fourth book Mill set out a number of possible future outcomes, rather than predicting one in particular. The first followed the Malthusian line that population grew quicker than supplies, leading to falling wages and rising profits. The second, per Smith, said if capital accumulated faster than population grew then real wages would rise. Third, echoing David Ricardo, should capital accumulate and population increase at the same rate, yet technology stay stable, there would be no change in real wages because supply and demand for labor would be the same. However growing populations would require more land use, increasing food production costs and therefore decreasing profits. The fourth alternative was that technology advanced faster than population and capital stock increased. The result would be a prospering economy. Mill felt the third scenario most likely, as he assumed technology advances would have to end at some point (Pressman 2006, 45). But on the prospect of continuing economic growth, Mill was more ambivalent:

I confess I am not charmed with the ideal of life held out by those who think that the normal state of human beings is that of struggling to get on; that the trampling, crushing, elbowing, and treading on each other's heels, which form the existing type of social life, are the most desirable lot of human kind, or anything but the disagreeable symptoms of one of the phases of industrial progress (Mill 1871).

Mill is also credited with being the first person to speak of supply and demand as a relationship rather than mere quantities of goods on markets (Stigler 1965, 1-15), the concept of opportunity cost, and the rejection of the wage fund doctrine (Pressman 2006, 46).

Theory

Classical theories revolved mainly around the role of markets in the economy. If markets worked freely and nothing prevented their rapid clearing then the economy would prosper. Any imperfections in the market that prevented this process should be dealt with by government. On the other hand, government interventions that inhibit the free flow of goods and services are detrimental. The main roles of government are therefore to ensure the free workings of markets using "supply-side policies" and to ensure a balanced budget.

The main theories used to justify this view were the "Free market theory," "Say's Law," and the "Quantity theory of money."

Free market theory

Classical economists assumed that if the economy was left to itself, then it would tend to full employment equilibrium. This would happen if the labor market worked properly. If there was any unemployment, then the following would happen:

- UNEMPLOYMENT——>INCREASED DEMAND FOR LABOR——>FALL IN WAGES——>EQUILIBRIUM RESTORED

As the "Demand curve" illustrates, it is argued that there is an inverse relationship between the wage rate (or price of labor) , depicted on the vertical (price) axis P, and the quantity of labor demanded, which is depicted (as quantity of any other goods) on the horizontal (quantity) axis Q. There is also a “supply” (of labor) curve S in this Diagram.

This negative relationship between the wage and the quantity of labor demanded is the result of two effects:

- Substitution effect

In a practical economic example, let the WAGE (P) mean PRICE per combination of Products 1 and 2 (for example, pizza and Italian bread) while QUANTITY of labor (Q) is the total output of Product 1 and Product 2. Let us now assume that the price of Product 2 (Italian bread) that uses the same technology, ingredients, know-how, buildings and so forth decreases, which reduces the opportunity cost of making pizza (Product 1).

Hence, some bread makers move into the pizza business to substitute for the lag in the overall demand for pizza. At this point, the original equilibrium point—E1 = intersection of [P1, Q1]—with constant wages on the line [P1, E1] moves to the right to intersect with D2, which is the expected optimum output of pizza. Hence, for some time, before the equilibrium is restored at [P2, D2], the quantity of labor demand is reduced, or is, at the best, constant ( apparently content with the lower wages on the line [P1, E1]) while, at all times, the labor supply is constant as seen in equilibria [P1, D1] and [P2, D2].

Eventually, an equilibrium occurs in a labor market at the combination of wages and employment at which market demand and supply intersect (as illustrated in the diagram).

- If the wage rate is above the equilibrium, the quantity of labor supplied exceeds the quantity demanded and a surplus occurs. In this case, the existence of unemployed workers will be expected to result in downward pressure on the wage rate until an equilibrium is restored.

- If the wage rate is below the equilibrium, a labor shortage will occur. Competition among firms for workers is expected to result in increases in the wage until an equilibrium occurs.

- Scale effect

The scale effect resulting from a wage increase is a bit more complex. As the wage rate rises, the scale effect involves the following chain of effects:

- higher wages result in higher average and marginal costs of production,

- higher average and marginal and average costs result in an increase in the equilibrium price of the product,

- as the price of the product rises, the equilibrium quantity of the product demanded declines (a reduction in the "scale" of production), and

- the reduction in output results in a reduction in the quantity of all inputs used to produce this product (including this category of labor).

Hence, classical economists were of the view that the economy is self-adjusting. In fact, in their view, because the economy tends to full-employment, there is no need for government to actively intervene. In fact, intervention may simply be destabilizing and inflationary. The key to long-term stable economic growth is therefore to:

- ensure free markets with no imperfections (through supply-side policies); and

- control the growth of the money supply to ensure low inflation.

The effect of supply-side policies can be seen in the above diagram when we assume only one price level, say P1, and we increase the level of output from Q1 to Q2, while the price level P1 remains stable. Supply-side policies as we have said are ones that reduce market imperfections. They may include:

- Improving education and training to make the work-force more occupationally mobile,

- reducing the level of benefits to increase the incentive for people to work,

- reducing taxation to encourage enterprise and encourage hard work,

- policies to make people more geographically mobile (ending rent controls, simplifying house buying, and so forth),

- reducing the power of trade unions to allow wages to be more flexible,

- removing any capital controls, and

- removing unnecessary regulations.

Say’s Law

Jean-Baptiste Say was adamant in his opposition to government intervention into the economy. Most succinctly stated, he declared that self-interest and the search for profits will push entrepreneurs toward satisfying consumer demand: "the nature of the products is always regulated by the wants of society," therefore "legislative interference is superfluous altogether" (Say 1803, 144).

It was in his Treatise (Say 1803) that Say outlined his famous law: Say's Law claims that total demand in an economy cannot exceed or fall below total supply in that economy or, as James Mill restated it, "production of commodities creates, and is the one and universal cause which creates a market for the commodities produced." In Say's language, "products are paid for with products" (1803, 153) or "a glut can take place only when there are too many means of production applied to one kind of product and not enough to another" (1803, 178-179). Say argued against claims that business was suffering because people did not have enough money and more money should be printed. Say argued that the power to purchase could be increased only by more production.

It is important to note that Say himself never used many of the later short definitions of Say's Law, including John Maynard Keynes' somewhat inaccurate version, "supply creates its own demand." Say's Law actually developed due to the work of many of his contemporaries and those who came after him. The work of James Mill, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, and others developed it into what is sometimes called the "law of markets" which was the framework of macroeconomics from the mid-1800s until the 1930s.

Quantity theory of money

Classical economists ascribe one other important role to the government: to control monetary growth. In this way, as predicted by the Quantity theory of money (QTM), they would be able to maintain low inflation.

The Quantity theory of money states that there is a direct relationship between the quantity of money in an economy and the level of prices of goods and services sold. According to QTM, if the amount of money in an economy doubles, price levels also double, causing inflation (the percentage rate at which the level of prices is rising in an economy). The consumer therefore pays twice as much for the same amount of the good or service.

This idea was first promoted in the seventeenth century by John Locke and David Hume. The original proposition was to refute Mercantilism's equation of money with wealth, and based on shrewd observation of the impact of the influx of precious metals from the New World. With the advent of fiat money (bank notes and other non-metallic forms) the possibility of hoarding money as wealth, which reduced the quantity effect, was lost. John Stuart Mill noted this in his development of the QTM, making clear that the medium-of-exchange function of money is essential to the effect. His work also laid the foundation for this theory to play a significant role in twentieth century economics, long after new theories of economics had replaced the classical tradition.

Impact in the nineteenth century

The rationality principle

Ricardian notions such as comparative advantage in international trade rest on the idea that people are rational (Ricardo, 1951). In other words, it is implied that traders produce goods that they can trade, and they sell to those who offer the highest price:

If one of the wine sellers were offering only four quarts for a bushel, the owner of the wheat will not give it to this wine seller if he knows that another will give him six or eight quarts for the same bushel (Lagueux 1997)

This type of thinking is neatly illustrated by the saga of the British Corn Laws, import tariffs designed to protect British corn against competition from cheaper foreign imports, and their eventual repealing thirty years later. The Corn Laws were adopted by the Tories who represented the landed class and greatly benefited from agricultural protections, and were designed to keep prices high after the Napoleonic Wars. They feared that a drop in prices due to foreign imports would harm them financially. The Whigs, on the other hand, were business owners. Following David Ricardo's economic views they believed a decrease in the price of grain would allow them to lower wages and through that increase their profits.

The Corn Laws had been passed in 1815, setting a fluctuating system of tariffs to stabilize the price of wheat in the domestic market. Ricardo argued that raising tariffs, despite being intended to benefit the incomes of farmers, would merely produce a rise in the prices of rents that went into the pockets of landowners. Furthermore, extra labor would be employed leading to an increase in the cost of wages across the board, and therefore reducing exports and profits coming from overseas business. In 1841, Sir Robert Peel became Conservative Prime Minister and Richard Cobden, a leading free trader, was elected for the first time. With Cobden's support Peel was persuaded to the position of the classical economists, and in 1846, the Corn Laws were repealed.

Exploitation theory

Exploitation theory was developed by Karl Marx. It states that profit is the result of the exploitation of wage earners by their employers. There are three aspects of classical economics which contribute to this exploitation theory. The two best known are:

- The labor theory of value and

- The iron law of wages.

Somewhat less prominent, but no less important, is the conceptual framework within which the exploitation theory is advanced. This framework is the belief that:

- Wages are the original and primary form of income, from which profits and all other non-wage incomes emerge as a deduction with the coming of capitalism and businessmen and capitalists.

It is on the basis of these beliefs that Adam Smith opened his chapter on wages in The Wealth of Nations with the words:

The produce of labour constitutes the natural recompense or wages of labour. In that original state of things, which precedes both the appropriation of land and the accumulation of stock, the whole produce of labour belongs to the labourer. He has neither landlord nor master to share with him (Smith 1776).

In these, and other passages, Smith clearly advances the primacy of wages doctrine. That is, the doctrine that in a pre-capitalist economy, in the "early and rude state of society," workers simply produce and sell commodities and do not buy in order to sell; the income the workers receive are wages. "Wages are the original income,” according to Smith. "All income in the pre-capitalist society is supposed to be wages, and no income is supposed to be profit … because workers are the only recipients of income" (Smith 1776).

At the same time, Smith advances the corollary doctrine that "profit emerges only with the coming of capitalism and is a deduction from what is naturally and, by implication, rightfully wages" (Smith 1776).

Within this framework, Marx applied the labor theory of value and the iron law of wages, and arrives at the exploitation theory.

Resting on the labor theory of value, which claims that value is intrinsic in a product according to the amount of labor that has been spent on producing the product, Marx stated that the value of a product is created by the workers who made that product and reflected in its finished price. Thus, workers are the fundamental creative source of new value. The income from this finished price is then divided between labor (wages), capital (profit), and expenses on raw materials. Property relations affording the right control of the workplace to capitalists are the devices by which the "surplus value" created by workers is appropriated by the capitalists. The wages received by workers do not reflect the full value of their work, because some of that value is taken by the employer in the form of profit. Therefore, "making a profit" essentially means taking away from the workers some of the value that results from their labor. This is what is known as capitalist exploitation.

Continuing contributions

Despite being overtaken by neoclassical economics in the latter part of the nineteenth century, many aspects of classical economic theory continue to inform and impact the world. Following are some examples.

Quantity theory of money

This theory, originating early and developed by John Stuart Mill, was formalized in the twentieth century by Irving Fisher. It has played a continuing role in economics, featuring in the work of Milton Friedman (1956). In its simplest form (the Fisher Equation) the theory is expressed as

- MV = PT

where each variable denotes the following:

- M = Money Supply

- V = Velocity of Circulation (the number of times money changes hands)

- P = Average Price Level

- T = Volume of Transactions of Goods and Services.

It is built on the principle of equation of exchange:

- Amount of Money x Velocity of Circulation = Total Spending

Another way to understand this theory is to recognize that money is like any other commodity. An increase in money supply causes prices to rise (inflation) as they compensate for the decrease in money’s marginal value.

Policies to control the quantity of money in circulation include:

- Open-market operations.

- Funding.

- Monetary-base control.

- Interest rate control.

Critique of exploitation theory

Despite the support which it seems to be giving to the exploitation theory, given that Marx used classical ideas such as the labor theory of value to develop it, classical economics provides the basis for turning the exploitation theory upside down. On the basis of Ricardo's concept of profit and J. S. Mill's proposition that "demand for commodities is not demand for labor," it is possible to show how profits, not wages, must be regarded as the original and primary form of income, from which other incomes emerge as a deduction.

Classical theory also reveals the labor of businessmen and capitalists has more fundamental responsibility for the production of products than the labor of wage earners, with the result that "labor's right to the whole produce" should mean the right of businessmen and capitalists to the sales receipts—a right which is accepted in the normal operations of a capitalist economy.

The classical doctrines of supply and demand, the wage fund, the distinction between value and riches, and the labor theory of value─modified along lines suggested by Ricardo and J. S. Mill and incorporating the advances in price theory made by Böhm-Bawerk─make possible an explanation of real wages. Böhm-Bawerk applied the discounting approach, criticizing exploitation theory (Bohm-Bawerk 1959).

For classical economics implies that it is false to claim that wages are the original form of income and that profits are a deduction from them. This becomes apparent, as soon as we define our terms along classical lines:

- Profit is the excess of receipts from the sale of products over the money costs of producing them—over, it must be repeated, the money costs of producing them.

- A capitalist is one who buys in order subsequently to sell for a profit.

- Wages are money paid in exchange for the performance of labor—not for the products of labor, but for the performance of labor itself.

On the basis of these definitions it follows that, if there are merely workers producing and selling their products, the money which they receive in the sale of their products is not wages. "Demand for commodities," to quote John Stuart Mill, "is not demand for labour. ... in buying commodities, one does not pay wages, and in selling commodities, one does not receive wages” (Mill 1976).

F. A. Hayek also contributed to this discourse, with such statements as:

The actual history of the connection between capitalism and the rise of the proletariat is almost the exact opposite of that which these theories of the expropriation of the masses suggest.

The proletariat which capitalism can be said to have 'created' was thus not a proportion of the population which would have existed without it and which it degraded to a lower level; it was an additional population which was enabled to grow up by the new opportunities for employment which capitalism provided. (Hayek, 1954)