|

|

| (47 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | {{Started}} | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{Paid}}{{2Copyedited}}{{copyedited}} |

| | | | |

| − | '''Apostasy''' is a term generally employed to describe the formal renunciation of one's religion, especially if the motive is deemed unworthy. In a technical sense, as used sometimes by sociology|sociologists without the pejorative connotations of the word, the term refers to renunciation ''and'' criticism of, or opposition to one's former religion. One who commits apostasy is an '''apostate''', or one who '''apostatises'''. Apostasy is generally not a self-definition: very few former believers call themselves apostates and they generally consider this term to be a pejorative. One of the possible reasons for this renunciation is loss of faith, another is the failure of alleged religious indoctrination or brainwashing. | + | '''Apostasy''' is the formal renunciation of one's religion. One who commits apostasy is called an '''apostate.''' Many religious faiths consider apostasy to be a serious [[sin]]. In some religions, an apostate will be excommunicated or shunned, while in certain [[Islamic]] countries today, apostasy is punishable by death. Historically, both [[Judaism]] and [[Christianity]] harshly punished apostasy as well, while the non-[[Abrahamic religions]] tend to deal with apostasy less strictly. |

| | | | |

| − | Many religious movements consider it a [[vice]] ([[sin]]), a corruption of the [[virtue]] of [[piety]] in the sense that when piety fails, apostasy is the result.

| + | Apostasy is distinguished from [[heresy]] in that the latter refers to the corruption of specific religious doctrines but is not a complete abandonment of one's faith. However, heretics are often declared to be apostates by their original religion. In some cases, heresy has been considered a more serious sin or crime than apostasy, while in others the reverse is true. |

| | | | |

| − | Several religious groups and even some states punish apostates. Apostates may be [[shunning|shunned]] by the members of their former religious group<ref>[http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,2-1470584,00.html ''Muslim apostates cast out and at risk from faith and family''], ''The Times'', February 05, 2005</ref> or worse. This may be the official policy of the religious group or may happen spontaneously, due in some sense to psycho-social factors as well. The Catholic Church may in certain very limited circumstances respond to apostasy by [[excommunication|excommunicating]] the apostate, while the writings of both ancient [[Judaism]] ([[Deuteronomy]] 13:6-10) and [[Islam]] (al-Bukhari, Diyat, bab 6) demand the death penalty for apostates.

| + | When used by sociologists, apostasy often refers to both renunciation and public criticism of one's former religion. Sociologists sometimes make a distinction between apostasy and "defection," which does not involve public opposition to one's former religion. |

| | + | {{toc}} |

| | + | Apostasy, as an act of religious conscience, has acquired a protected legal status in international law by the [[United Nations]], which affirms the right to change one's religion or belief under Article 18 of the [[Universal Declaration of Human Rights]]. |

| | | | |

| | + | ==Apostasy in the Abrahamic religions== |

| | + | ===Judaism=== |

| | + | In the [[Hebrew Bible]], apostasy is equated with rebellion against [[God]], [[His Law]], and and worshiping any god other than the Hebrew deity, [[Yahweh]]. The penalty for apostasy in [[Deuteronomy]] 13:1-10 is death. |

| | | | |

| − | The difference between apostasy and heresy is that the latter refers to rejection or corruption of certain doctrines, not to the complete abandonment of one's religion. Heretics claim to still be following a religion (or to be the "true followers"), whereas apostates reject it.

| + | <blockquote>That [[prophet]] or that dreamer (who leads you to worship of other gods) shall be put to death, because… he has preached apostasy from [[Yahweh|The Lord]] your God… If your own full brother, or your son or daughter, or your beloved wife, or your intimate friend, entices you secretly to serve other gods… do not yield to him or listen to him, nor look with pity upon him, to spare or shield him, but kill him… You shall stone him to death, because he sought to lead you astray from the Lord, your God.</blockquote> |

| − | | |

| − | The term is also used to refer to renunciation of belief in a cause other than religion, particularly in politics. Conversely, some Atheism|atheists and Agnosticism|agnostics use the term "deconversion" to describe loss of faith in a religion. Self-described "Freethought|Freethinkers" and those who may view traditional religion negatively may see it as gaining rationality and respect for the [[scientific method]].

| |

| | | | |

| − | Other terms to describe leaving a faith and the associated process are treated in religious disaffiliation.

| + | However, there are few instances when this harsh attitude seems to have been enforced. Indeed, the constant reminders of the [[prophet]]s and biblical writers warning against [[idolatry]] demonstrate that [[Deuteronomy]]'s standard was rarely enforced as the "law of the land." Indeed, modern scholars believe that the [[Book of Deuteronomy]] did not actually originate in the time of Moses, as is traditionally believed, but in the time of King [[Josiah]] of Judah in the late seventh century B.C.E.. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Sociological definitions==

| + | There are several examples where strict punishment was indeed given to those who caused the [[Israelites]] to violate their faith in [[Yahweh]] alone. When the Hebrews were about to enter [[Canaan]], Israelite men were reportedly led to worship the local deity [[Baal]]-Peor by [[Moabite]] and [[Midianite]] women. One of these men was slain together with his Midianite wife by the priest [[Phinehas]] (Numbers 25). The Midianite crime was considered so serious that [[Moses]] launched a war of extermination against them. |

| − | {{details|The Politics of Religious Apostasy}}

| |

| − | The American sociologist Lewis A. Coser (following the German philosopher and sociologist Max Scheler) holds an apostate to be not just a person who experienced a dramatic change in conviction but “''a man who, even in his new state of belief, is spiritually living not primarily in the content of that faith, in the pursuit of goals appropriate to it, but only in the struggle against the old faith and for the sake of its negation.''"<ref>Lewis A. Coser ''The Age of the Informer'' Dissent:1249-54, 1954</ref><ref name="bromley1998">Bromley, David G. (Ed.) ''The Politics of Religious Apostasy: The Role of Apostates in the Transformation of Religious Movements'' CT, Praeger Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0-275-95508-7</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | The American sociologist David G. Bromley defined the apostate role as follows and distinguished it from the defection|defector and whistleblower roles.<ref name="bromley1998"/>

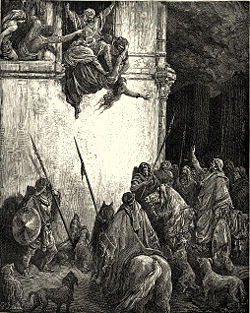

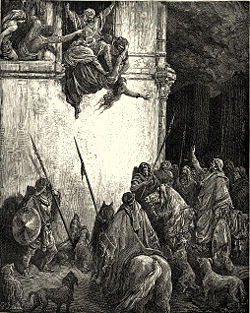

| + | [[Image:The Death of Jezebel.jpg|thumb|250px|left|''The Death of Jezebel'' by [[Gustave Doré]].]] |

| − | *''Apostate role'': defined as one that occurs in a highly polarized situation in which an organization member undertakes a total change of loyalties by allying with one or more elements of an oppositional coalition without the consent or control of the organization. The narrative is one which documents the quintessentially evil essence of the apostate's former organization chronicled through the apostate's personal experience of capture and ultimate escape/rescue.

| |

| − | *''Defector role'': an organizational participant negotiates exit primarily with organizational authorities, who grant permission for role relinquishment, control the exit process, and facilitate role transmission. The jointly constructed narrative assigns primary moral responsibility for role performance problems to the departing member and interprets organizational permission as commitment to extraordinary moral standards and preservation of public trust.

| |

| − | *''Whistleblower role'': defined here as one in which an organization member forms an alliance with an external regulatory unit through offering personal testimony concerning specific, contested organizational practices that is then used to sanction the organization. The narrative constructed jointly by the whistleblower and regulatory agency is one which depicts the whistleblower as motivated by personal conscience and the organization by defense of public interest.

| |

| | | | |

| − | Stuart A. Wright, an American sociologist and author, asserts that apostasy is a unique phenomenon and a distinct type of religious defection, in which the apostate is a defector "who is aligned with an oppositional coalition in an effort to broaden the dispute, and embraces public claimsmaking activities to attack his or her former group." <ref> Wright, Stuart, A., '' Exploring Factors that Shatpe the Apostate Role'', in Bromley, David G., ''The Politics of Religious Apostasy'', pp. 109, Praeger Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0-275-95508-7</ref>

| + | Perhaps the most remembered story of Israelite apostasy is that brought on by [[Jezebel]], the wife of King [[Ahab]]. Jezebel herself was not an Israelite, but was originally a princess of the coastal [[Phoenicia]]n city of [[Tyre]], in modern day [[Lebanon]]. When Jezebel married Ahab (who ruled c. 874–853 B.C.E..E.), she persuaded him to introduce [[Baal]] worship. The prophets [[Elijah]] and [[Elisha]] condemned this practice as a sign of being unfaithful to Yahweh. |

| | | | |

| − | ==In international law==

| + | Elijah ordered 450 prophets of Baal slain after they had lost a famous contest with him on [[Mount Carmel]]. Elijah's successor, [[Elisha]], caused the military commander [[Jehu]] to be anointed as king of Israel while Ahab's son, [[Jehoram]], was still on the throne. Jehu himself killed Jehoram and then went to Jezebel's palace and ordered her slain as well. |

| − | The United Nations Commission on Human Rights, considers the recanting of a person's religion a [[human rights|human right]] legally protected by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights: "The Committee observes that the freedom to 'have or to adopt' a religion or belief necessarily entails the freedom to choose a religion or belief, including the right to replace one's current religion or belief with another or to adopt atheistic views [...] Article 18.2 bars coercion that would impair the right to have or adopt a religion or belief, including the use of threat of physical force or penal sanctions to compel believers or non-believers to adhere to their religious beliefs and congregations, to recant their religion or belief or to convert."<ref>CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.4, General Comment No. 22., 1993</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | {{seealso|Religious conversion}}

| + | The [[Bible]] speaks of other notable defections from the Jewish faith: For example, Isaiah 1:2-4, or Jeremiah 2:19, and Ezekiel 16. Indeed, the Bible is replete with examples of Israelites worshiping other gods than Yahweh and being punished for this by God, though rarely by other Israelites. Israelite kings were often judged guilty of apostasy. Examples include Ahab (I Kings 16:30-33), Ahaziah (I Kings 22:51-53), Jehoram (2 Chronicles 21:6,10), Ahaz (2 Chronicles 28:1-4), Amon (2 Chronicles 33:21-23), and others. Even as great a king as Solomon is judged guilty of honoring other gods: "On a hill east of Jerusalem, Solomon built a high place for [[Chemosh]] the detestable god of [[Moab]], and for [[Molech]] the detestable god of the [[Ammonites]]" (1 Kings 11:7). |

| | | | |

| − | ==In Christianity==

| + | However, as late as the time of the prophet [[Jeremiah]] in the early sixth century B.C.E., the worship of [[Canaanite]] gods continued unabated, as he complained: |

| | | | |

| − | [[Image:Julian.jpg|thumb|Flavius Claudius Iulianus, [[Roman Emperor]] (361-363), was raised as Christian, but rejected this faith upon becoming emperor. His Christian enemies called him ''apostate'', and therefore he is still widely known in English as [[Julian the Apostate]].]]

| + | <blockquote>Do you not see what they are doing in the towns of Judah and in the streets of Jerusalem? The children gather wood, the fathers light the fire, and the women knead the dough and make cakes of bread for the Queen of Heaven. They pour out drink offerings to other gods to provoke me to anger (Jeremiah 7:17-18).</blockquote> |

| − | The prophecy in [[Second Epistle to the Thessalonians|the Second Epistle to the Thessalonians]] has often been cited concerning apostasy:

| |

| | | | |

| − | :''"Let no man deceive you by any means, for unless there come a revolt first, and the man of sin be revealed, the son of perdition,"''<ref>2 Thessalonians 2:3 [[Douay Rheims]]</ref>

| + | According to biblical tradition, the apostasy of the Israelites led to destruction of the northern [[Kingdom of Israel]] in 722-821 B.C.E., and the exile of the citizens of the southern [[Kingdom of Judah]] to [[Babylon]], as well as the destruction of the [[Temple of Jerusalem]] in 586 B.C.E. After the [[Babylonian Exile]], the Deuteronomic code seems to have been taken more seriously, but examples of its enforcement are scanty at best. Periods of apostasy were evident, however. The most well known of these came during the administration of the Seleucid Greek ruler [[Aniochus IV]] Epiphanes in the second century C.E., who virtually banned Jewish worship and forced many Jews to worship at pagan altars until the [[Macabeean revolt]] established an independent Jewish dynasty. |

| − | :''"Let no man deceive you by any means: for that day shall not come, except there come a falling away first, and that man of sin be revealed, the son of perdition;"''<ref>2 Thessalonians 2:3 [[King James Version]]</ref>

| |

| − | :''"Let no one in any way deceive you, for it will not come unless the apostasy comes first, and the man of lawlessness is revealed, the son of destruction"''<ref>2 Thessalonians 2:3 [[New American Standard Bible]]</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | Members of [[The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints]] (Mormons) believe that this foretold apostasy, "The [[Great Apostasy]]," began with the death of the early apostles and continued into the early nineteenth century. Mormons believe that the "priesthood" (the authority to act in God's name) was lost, and that the church as it existed in the days of Christ needed to be restored to its original condition. They believe the "restoration" was performed by Joseph Smith.

| + | At the beginning of the Common Era, Judaism faced a new threat of apostasy from the new religion of [[Christianity]]. At first, believers in Jesus were treated as a group within Judaism (see Acts 21), but were later considered heretical, and finally—as Christians began proclaiming the end of the [[Abraham]]ic covenant, the divinity of Christ, and the doctrine of the Trinity—those Jews who converted to belief in Jesus were treated as apostates. |

| | | | |

| − | Many non-Mormons would argue that, in reference to the church as a whole, the Bible speaks of apostasies, but only of partial apostasies (see I Tim. 4:1, II Tim. 3:1-5). A partial apostasy (some, or a group of people turning from the faith) would not mean the church ceased to exist; it would only mean its size diminished. This view would hold that all of the proof texts suggested by Mormons would actually deal with either apostasy of Israel (Amos 8:11, Isa. 29) a partial apostasy during the church age, or apostasy during the tribulation period (future).

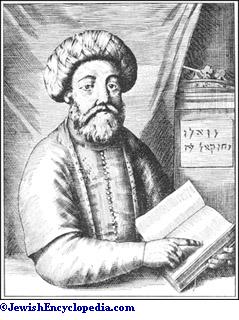

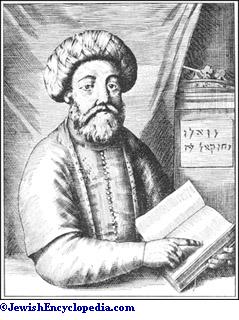

| + | [[Image:Shabbatai1.jpg|thumb|Shabbatai Tsevi, thought by many Jews to be the Messiah, until he apostasized to Islam.]] |

| | | | |

| − | The apostasy can alternatively be interpreted as the pre-tribulation [[Rapture]] of the Church. This is because apostasy means departure (translated so in the first seven English translations).<ref>Dr. Thomas Ice, ''Pre-Trib Perspective'', March 2004, Vol.8, No.11.</ref>

| + | During the [[Spanish Inquisition]], apostasy took on a new meaning. Forcing Jews to renounce their religion under threat of expulsion or even death complicated the issue of what qualified as "apostasy." Many rabbis considered the behavior of a Jew, rather than his professed public belief, to be the determining factor. Thus, large numbers of Jews became [[Marranos]], publicly acting as Christians, but privately acting as Jews as best they could. On the other hand, some well-known Jews converted to Christianity with enthusiasm and even engaged in public debates encouraging their fellow Jews to apostasize. |

| | | | |

| − | Regarding apostasy on an individual level, some denominations quote Jude and Titus 3:10 saying that an apostate or heretic needs to be "rejected after the first and second admonition." Hebrews 6:4-6 notes the impossibility of those who have fallen away "to be brought back to repentance."

| + | A particularly well known case of apostasy was that of [[Shabbatai Zevi]] in 1566. Shabbatai was a famous mystic and kabbalist, who was accepted by a large portion of Jews as the [[Messiah]], until he converted (under threat of execution) to Islam. Yet, Shabbatai Zevi retained a few die-hard Jewish followers who accepted his new career as a Muslim [[Sufism|Sufi]] leader--sharing the experience of so many crypto-Jews of that age—and who claimed that he was uniting the mystical essence of Judaism and Islam in his person. |

| | | | |

| − | Jesus himself seemed fully aware of the individuals' loss of faith. His parable of the Sower in Luke chapter 8 talks of a farmer who sowed seed that fell along a path and was eaten by birds, seed that fell on a rock and whithered for lack of moisture, seed that was choked out by thorns, and seed that fell on good soil and yielded good crops, reflecting well the states of disbelief, apostasy of one type or another, and belief. In another situation, John 6:66 relates that, "From this time many of his disciples turned back and no longer followed him." In speaking of the end times, Jesus said, "At that time many will turn away from the faith and will betray and hate each other." (Matthew 24:10) There is also the possibility that Judas Iscariot's betrayal was related to apostasy (as opposed to never having believed).

| + | It should also be noted that from the time of early [[Talmud]]ic sages in the second century C.E., the rabbis took the attitude that Jews could hold to a variety of theological attitudes and still be considered a Jew. (This contrasts with the Christian view that without adhering to the correct belief—called [[orthodoxy]]—one was not a true Christian.) In modern times, this attitude was exemplified by Abraham Isaac Kook (1864-1935), the first Chief Rabbi of the Jewish community in the British Mandate for [[Palestine]], who held that even Jewish [[atheist]]s were not apostate. Kook taught that, in practice, atheists were actually helping true religion to burn away false images of God, thus in the end, serving the purpose of true [[monotheism]]. |

| | | | |

| − | The apostles also acknowledged individual apostasy. In addition to witnessing the aforementioned loss of faith by many disciples of Jesus recorded in John 6, Peter said that for believers in Christ who knowingly turn away from their faith that "the last state has become worse for them than the first" (2 Peter 2:20-22). John addresses the same problem (I John 2:18-19). The apostle Paul cited Hymenaeus and Alexander as specific examples of those who had rejected the faith (I Timothy 1:20).

| + | Sanctions against apostasy in Judaism today include the Orthodox tradition of shunning a person who leaves the faith, in which the parents formally mourn their lost child and treat him or her as dead. Apostates in the [[State of Israel]] are forbidden to marry other Jews. |

| | | | |

| − | The [[Roman Catholic Church|Catholic Church]] holds that in certain circumstances apostasy can cause one to be [[excommunication|excommunicated]] [[Latae sententiae|''latae sententiae'']].

| + | ===In Christianity=== |

| | + | Apostasy in [[Christianity]] began early in its history. [[Saint Paul]] started out his career attempting to influence Christians to apostasize from the new faith (Acts 8) and revert to orthodox Judaism. Later, when Christianity separated itself from [[Judaism]], Jewish Christians who kept the [[Mosaic Law]] were considered either heretics or apostates. |

| | | | |

| − | In the first centuries of the Christian era - as well as other times such as 17th century [[Japan]] (See [[Kakure Kirishitan]]) - apostasy was most commonly induced by persecution, and was indicated by some outward act, such as offering incense to a heathen deity or blaspheming the name of Christ.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} (The readmission of such apostates to the church was a matter that occasioned serious controversy.) The emperor Julian's "Apostasy" is discussed under [[Julian the Apostate]]. In the Catholic Church the word has been applied to the renunciation of monastic vows ''(apostasis a monachatu)''{{Fact|date=February 2007}}, and to the abandonment of the clerical profession for the life of the world ''(apostasis a clericatu)''{{Fact|date=February 2007}}, though this usage is a technical one, and refers to the renunciation of the respective states. Such defection was formerly often punished severely{{Fact|date=February 2007}}. | + | In Christian tradition, apostates were to be shunned by other members of the church. Titus 3:10 indicates that an apostate or heretic needs to be "rejected after the first and second admonition." Hebrews 6:4-6 affirms the impossibility of those who have fallen away "to be brought back to repentance." |

| | | | |

| − | ''See also [[Great Apostasy]]; for an [[Arminianism|Arminian]] doctrine of individual apostasy, see [[Conditional Preservation of the Saints]].''

| + | Many of the early [[martyr]]s died for their faith rather than apostasizing, but others gave in to the persecutors and offered sacrifice to the Roman gods. It is difficult to know how many quietly returned to pagan beliefs or to Judaism during the first centuries of Christian history. |

| | | | |

| − | ==In Islam==

| + | [[Image:JulianusII-antioch(360-363)-CNG.jpg|thumb|left|Julian the Apostate]] |

| − | {{main|Apostasy in Islam|Takfir}}

| |

| − | Islam as it has been practiced for hundreds of years does enforce harsh penalties for apostasy. However the Quran itself is silent on the ''punishment'' for apostasy, though not the subject itself. The Quran speaks repeatedly of people going back to unbelief after believing, but does not confirm that they should be killed or punished.

| |

| | | | |

| − | In Islam, apostasy is called "''ridda''" ("turning back") and it is considered by Muslims to be a profound insult to God. A person born of Muslim parents that rejects Islam is called a "''murtad fitri''" (natural apostate), and a person that converted to Islam and later rejects the religion is called a "''murtad milli''" (apostate from the community).

| + | With the conversion of Emperor [[Constantine I]] and the later establishment of Christianity as the official religion of the [[Roman Empire]], the situation changed dramatically. Rather than being punished by the state if one refused to apostasize, a person would be sanctioned for apostasy, which became a civil offense punishable by law. This changed briefly under the administration of Emperor Julianus II (331-363 C.E.)—known to history as [[Julian the Apostate]] for his policy of divorcing the Roman state from its recent union with the Christian Church. |

| | | | |

| − | The question of the penalties imposed in Islam (i.e. in the [[Qur'an]] or under [[shariah]] law) for apostasy is a highly controversial topic that is passionately debated by various scholars. On this basis, according to most scholars, if a Muslim consciously and without coercion declares their rejection of Islam and does not change their mind after the time given to him/her by a judge for research, then the penalty for male apostates is the death penalty, or, for women, life imprisonment. However, this view has been rejected by an extremely small minority of modern Muslim scholars (eg [[Hasan al-Turabi]]), who argues that the ''[[hadith]]'' in question should be taken to apply only to political betrayal of the Muslim community, rather than to apostasy in general.<ref>http://www.islamonline.net/english/Contemporary/2003/05/Article01a.shtml</ref> These scholars argue for the freedom to convert to and from Islam without legal penalty, and consider the aforementioned ''Hadith'' quote as insufficient confirmation of harsh punishment; they regard apostasy as a serious crime, but undeserving of the death penalty. Today apostasy is punishable by death in the countries of [[Saudi Arabia]], [[Yemen]], [[Iran]], [[Sudan]], [[Afghanistan]], [[Mauritania]], the [[Comoros]] and, most likely, [[Iraq]].<ref>http://www.aina.org/news/20050202111020.htm</ref><ref>http://www.freedomhouse.org/religion/news/bn2005/bn-2005-2006%20-04-07.htm</ref> Similarly, [[blasphemy]] is punishable by death in [[Pakistan]]. In [[Qatar]] apostasy is a capital offense, but no executions have been reported for it.<ref>http://www.freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=22&year=2006&country=7042</ref>

| + | For more than a millennium after Julian's death, Christian states used the power of the sword to protect the Church against apostasy and [[heresy]]. Apostates were deprived of their civil as well as their religious rights. Torture was freely employed to extract confessions and to encourage recantations. Apostates and schismatics were not only excommunicated from the Church but persecuted by the state. |

| | | | |

| − | The hadith "''Whosoever changes his religion, Kill Him''," has been used both by supporters of the death penalty as well as critics of Islam. Islamic scholars point out it is important to understand the hadith in proper historical context. The order was at a time when the nascient Muslim community in Medina was fighting for its very life, and there were many schemes, by which the enemies of Islam would try to entice rebellion and discord within the community.<ref>http://www.irfi.org/articles/articles_251_300/is_killing_an_apostate_in_the_is.htm</ref> Clearly any defection would have serious consequences for the Muslims, and the hadith may well be about [[treason]], rather than just apostasy. It must also be pointed out that under the terms of the [[Treaty of Hudaybiyyah]], any Muslim who returned to Mecca was not to be returned, terms which the Prophet accepted. Despite this historical point Islamic law as currently practiced does not allow the freedom for the individual to choose one's religion. | + | Apostasy on a grand scale took place several times. The “[[Great Schism]]” between Eastern Orthodoxy and Western Catholicism in the eighth century resulted in mutual excommunication. The [[Protestant Reformation]] in the sixteenth century further divided Christian against Christian. Sectarian groups often claimed to have recovered the authentic faith and practice of the [[New Testament]] Church, thereby relegating rival versions of Christianity to the status of apostasy. |

| | | | |

| − | The [[Qur'an]] says:

| + | After decades of warfare in Europe, Christian tradition gradually came to accept the principle of tolerance and [[religious freedom]]. Today, no major Christian denomination calls for legal sanctions against those who apostasize, although some denominations do excommunicate those who turn to other faiths, and some groups still practice [[shunning]]. |

| | | | |

| − | {{quote|Let there be no compulsion in the religion: Clearly the ''Right Path'' (i.e. Islam) is distinct from the crooked path.|[[Qur'an]]|{{quran-usc|2|256}}||}}

| + | ===In Islam=== |

| | + | Islam imposes harsh legal penalties for apostasy to this day. The [[Qur'an]] itself has many passages that are critical of apostasy, but is silent on the proper punishment. In the [[Hadith]], on the other hand, the [[death penalty]] is explicit. |

| | | | |

| − | {{quote|A section of the 'People of the Book' (Jews and Christians) says: "Believe in the morning what is revealed to the believers (Muslims), but reject it at the end of the day; perchance they may (themselves) turn back (from Islam).|[[Qur'an]]|{{quran-usc|3|72}}||}}

| + | [[Image:Salman Rushdie.jpg|thumb|Author [[Salman Rushdie]] is considered an apostate from Islam and was given a death sentence by several Islamic authorities.]] |

| | | | |

| − | {{quote|But those who reject faith after they accepted it, and then go on adding to their defiance of faith, never will their repentance be accepted; for they are those who have (of set purpose) gone astray.|[[Qur'an]]|{{quran-usc|3|90}}||}}

| + | Today, apostasy is punishable by death in [[Saudi Arabia]], [[Yemen]], [[Iran]], [[Sudan]], [[Afghanistan]], [[Mauritania]], and the [[Comoros]]. In [[Qatar]], apostasy is a also capital offense, but no executions have been reported for it. Most other Muslim states punish apostasy by both whipping and imprisonment. |

| | | | |

| − | {{quote|Those who [[Blasphemy|blasphemed]] and back away from the ways of [[Allah]] and die as blasphemers, Allah shall not forgive them.|[[Qur'an]]|{{quran-usc|4|48}}||}}

| + | A few examples of passages in the Qur'an relevant to apostasy: |

| | | | |

| − | {{quote|Those who believe, then reject faith, then believe (again) and (again) reject faith, and go on increasing in unbelief,- Allah will not forgive them nor guide them on the way.|[[Qur'an]]|{{quran-usc|4|137}}||}}

| + | *"Let there be no compulsion in the religion: Clearly the Right Path (i.e. Islam) is distinct from the crooked path" (2.256). |

| | | | |

| − | {{quote|O ye who believe! If any from among you turn back from his faith, soon will Allah produce a people whom He (Allah) will love as they will love Him lowly with the believers, Mighty against the rejecters, fighting in the way of Allah, and never afraid of the reproachers of such as find fault. That is the Grace of Allah which He will bestow on whom He (Allah) pleases. And Allah encompasses all, and He knows all things.|[[Qur'an]]|{{quran-usc|5|54}}||}}

| + | *"Those who reject faith after they accepted it, and then go on adding to their defiance of faith, never will their repentance be accepted; for they are those who have (purposely) gone astray" (3:90). |

| | | | |

| − | The [[Hadith]] (the body of quotes attributed to [[Muhammad]]) includes statements taken as supporting the death penalty for apostasy, such as:

| + | *"Those who believe, then reject faith, then believe (again) and (again) reject faith, and go on increasing in unbelief, Allah will not forgive them nor guide them on the way" (4:137). |

| | | | |

| − | *Kill whoever changes his religion. {{bukhari|9|84|57}}

| + | The [[Hadith]], the body of traditions related to the life of the prophet [[Muhammad]], mandates the death penalty for apostasy: |

| | | | |

| − | *The blood of a Muslim who confesses that none has the right to be worshipped but Allah and that I am His Apostle, cannot be shed except in three cases: In [[Qisas]] for murder, a married person who commits illegal sexual intercourse and the one who reverts from Islam (apostate) and leaves the Muslims. {{bukhari|9|83|17}} | + | *"Kill whoever changes his religion" (Sahih Bukhari 9:84:57). |

| | | | |

| − | [[Javed Ahmad Ghamidi]], a [[Pakistan]]i [[Islamic scholar]], writes that punishment for apostasy was part of Divine punishment for only those who denied the truth even after clarification in its ultimate form by [[Muhammad]] (he uses term [[Itmam al-hujjah]]), hence, he considers this command for a particular time and no longer punishable.<ref>[[Javed Ahmad Ghamidi]], [http://www.renaissance.com.pk/novsps966.html The Punishment for Apostasy], Renaissance - Monthly Islamic Journal, [[Al-Mawrid]], 6(11), November, 1996</ref>

| + | *"The blood of a Muslim… cannot be shed except in three cases: …Murder …a married person who commits illegal sexual intercourse, and the one who reverts from Islam and leaves the Muslims" (Sahih Bukhari 9:83:17). |

| | | | |

| − | In 2006, [[Abdul Rahman (convert)|Abdul Rahman]], the Afghan convert from Islam to Christianity has attracted worldwide attention about where Islam stood on religious freedom. Prosecutors asked for the death penalty for him. However, under heavy pressure from foreign governments, the Afghan government claimed he was mentally unfit to stand trial and released him.

| + | Some Muslim scholars argue that such traditions are not binding and can be updated to be brought into line with modern [[human rights]] standards. However, the majority still hold that if a Muslim consciously and without coercion declares his rejection of Islam, and does not change his mind, then the penalty for male apostates is death and for women is life imprisonment. |

| | | | |

| − | [[Islamonline.net|Islam Online]], a hugely popular Muslim website, contains a fatwa dated 21 March 2004 and ascribed to 'IOL Shariah Researchers' says: | + | ==Apostasy in Eastern religions== |

| | + | Oriental religions normally do not sanction apostasy to the degree that [[Judaism]] and [[Christianity]] did in the past and [[Islam]] still does today. However, people do apostasize from Eastern faiths. Evangelical Christian converts from [[Hinduism]], for example, often testify to the depravity of the former lives as devotees of [[idolatry]] and [[polytheism]]. Converts from [[Buddhism]] likewise speak of the benefits of being liberated from the worship of "idols." [[Sikh]] communities have reported a rising problem of apostasy among their young people in recent years.<ref>Alice Barsarke, Apostasy and the Future of Sikhsim.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | * "If a sane person who has reached puberty voluntarily apostatizes from Islam, he deserves to be punished. In such a case, it is obligatory for the caliph (or his representative) to ask him to repent and return to Islam. If he does, it is accepted from him, but if he refuses, he is immediately killed."<ref>[http://www.islamonline.net/servlet/Satellite?pagename=IslamOnline-English-Ask_Scholar/FatwaE/FatwaE&cid=1119503544134 Islam Online]</ref>No one besides the caliph or his representative may kill the apostate. If someone else kills him, the killer is disciplined (for arrogating the caliph's prerogative and encroaching upon his rights, as this is one of his duties).

| + | Apostates from traditional faiths sometimes face serious sanctions if they marry members of an opposing faith. Hindu women in India who marry Muslim men, for example, sometimes face [[ostracism]] or worse from their clans. Sikhs who convert to Hinduism do so at the risk of not being welcome in their communities of origin. In authoritarian Buddhist countries, such as today's [[Burma]], conversion to a religion other than Buddhism likewise has serious social consequences. |

| | + | |

| | + | ==Apostasy from new religious movements== |

| | + | As with [[Christianity]] and [[Islam]] in their early days, [[New Religious Movement]]s (NRMs) have faced the problem of apostasy among their converts due to pressure from family, society, and members simply turning against their newfound faith. |

| | | | |

| − | ==In Judaism==

| + | In the 1980s, numbers of members of NRM members apostasized under the pressure of [[deprogramming]], in which they were kidnapped by agents of their family and forcibly confined in order to influence them to leave the group. (Deprogramming was criminalized in the United States and is no longer common. The practice reportedly continues in Japan.) Part of the "rehabilitation" process in deprogramming involved requiring a person to publicly criticize his or her former religion—a true act of apostasy. Subjects of deprogramming sometimes faked apostasy in order to escape from forcible confinement and return to their groups. In other cases, the apostasy was genuine, spurred by pressure from the member's family. |

| − | {{Mergefrom|Jews in apostasy|date=April 2007}}

| |

| − | {{seealso|yetzia bish'eila|List of converts to Christianity#From Judaism|}}

| |

| − | {{seealso|Spanish_inquisition}}

| |

| − | The term apostasy is also derived from [[Greek language|Greek]] ἀποστάτης, meaning "political rebel," as applied to rebellion against God, its law and the faith of [[Israelites|Israel]] (in [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] מרד) in the Hebrew Bible.

| |

| | | | |

| − | Other expressions for apostate as used by rabbinical scholars are "mumar" (מומר, literally "the one that is changed") and "poshea yisrael" (פושע ישראל, literally, "transgressor of Israel"), or simply "kofer" (כופר, literally "denier").

| + | [[Image:Steven Hassan Headshot.jpg|thumb|150px|Steven Hassan, an apostate member of the [[Unification Church]] who was kidnapped and deprogrammed, then became a deprogrammer and a "thought reform consultant."]] |

| | | | |

| − | The [[Torah]] states: | + | The decline of deprogramming coincided with sociological data that many members of NRMs defect on their own, belying the deprogrammers' contention that members were psychologically trapped and that leaving was nearly impossible without the intense effort that their services provided. Most of these defectors do not become apostates in the public sense. They may exhibit a range of attitudes towards their former involvement, including: Appreciation—but it was time to move on; a sense of failure that they could not live up to the group's standards; resentment against the leadership for hypocrisy and abuse of their authority; or a choice to engage in worldly activity that violated the group's membership code. |

| | | | |

| − | [[Deuteronomy]] 13:6-10: | + | Apostates of NRMs make a number of allegations against their former group and its leaders. This list includes: Unkept promises, [[sexual abuse]] by the leader, irrational and contradictory teachings, deception, financial exploitation, demonizing of the outside world, abuse of power, [[hypocrisy]] of the leadership, unnecessary secrecy, discouragement of [[critical thinking]], [[brainwashing]], [[mind control]], [[pedophilia]], and a leadership that does not admit any mistakes. While some of these allegations are based in fact, others are exaggerations and outright falsehoods. Similar allegations have been made made by apostates of traditional religions. |

| − | :''If thy brother, the son of thy mother, or thy son, or thy daughter, or the wife of thy bosom, or thy friend, which [is] as thine own soul, entice thee secretly, saying, ''Let us go and serve other gods'', which thou hast not known, thou, nor thy fathers; [Namely], of the gods of the people which [are] round about you, nigh unto thee, or far off from thee, from the [one] end of the earth even unto the [other] end of the earth; Thou shalt not consent unto him, nor hearken unto him; ''neither shall thine eye pity him'', neither shalt thou spare, ''neither shalt thou conceal him: But thou shalt surely kill him''; thine hand shall be first upon him to put him to death, and afterwards the hand of all the people. And thou shalt stone him with stones, that he die; because he hath sought to thrust thee away from the Lord thy God, which brought thee out of the land of Egypt, from the house of bondage.''<ref>[[Deuteronomy]] [http://www.apostolic-churches.net/bible/search/list/?search_book=Deuteronomy&search_chapter_verse=13&varchapter_verse=13:6 13:6-10]</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | The prophetic writings of Isaiah and Jeremiah provide many examples of defections of faith found among the Israelites (e.g., Isaiah 1:2-4 or Jeremiah 2:19), as do the writings of the prophet Ezekiel (e.g., Ezekiel 16 or 18). Israelite kings were often guilty of apostasy, examples including Ahab (I Kings 16:30-33), Ahaziah (I Kings 22:51-53), Jehoram (2 Chronicles 21:6,10), Ahaz (2 Chronicles 28:1-4), or Amon (2 Chronicles 33:21-23) among others. (Amon's father Manasseh was also apostate for many years of his long reign, although towards the end of his life he renounced his apostasy. Cf. 2 Chronicles 33:1-19) | + | The roles that apostates play in opposition to NRMs is a subject of considerable study among sociologists of religion. Some see the NRMs as modern laboratories replicating the conditions of early [[Christianity]], or any of the major religions in their formative years. One noted study proposes that stories of apostates are likely to paint a caricature of the group, shaped by the apostate's current role rather than his objective experience in the group.<ref>David G. Bromley, et al. (eds.), ''Brainwashing Deprogramming Controversy: Sociological, Psychological, Legal, and Historical Perspectives'' (Edwin Mellen Press, 1984, ISBN 0889468680), 156.</ref> Sociologist [[Lewis A. Coser]] holds an apostate to be not just a person who experienced a dramatic change in conviction but one who, "is spiritually living… in the struggle against the old faith and for the sake of its negation."<ref>Lewis A. Coser, ''The Age of the Informer'' Dissent: 1249-54, 1954.</ref> [[David Bromley]] defined the apostate role and distinguished it from the ''[[defection|defector]]'' and ''[[whistleblower]]'' roles. Stuart A. Wright asserts that apostasy is a unique phenomenon and a distinct type of religious defection, in which the apostate is a defector "who is aligned with an oppositional coalition in an effort to broaden the dispute, and embraces public claimsmaking activities to attack his or her former group."<ref>Stuart A. Wright, ''Exploring Factors That Shape the Apostate Role,'' in David G. Bromley, ''The Politics of Religious Apostasy'' (Praeger Publishers, 1998, ISBN 0275955087).</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | [[Paul of Tarsus]] was accused of apostasy by the council of [[James the Just|James]] and the elders, for teaching apostasy from the law given by Moses (Acts 21:17-26). Scholars consider this the reason by which some early Christians, such as the [[Ebionites]], repudiated Paul for being an apostate.

| + | ==In international law== |

| − | | + | [[Image:EleanorRooseveltHumanRights.gif|thumb|250px|Eleanor Roosevelt holds a copy of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.]] |

| − | In the [[Talmud]], [[Elisha Ben Abuyah]] (known as Aḥer) is singled out as an apostate and [[epicurean]] by the [[Pharisees]].

| + | Although the term "apostate" carries negative connotations, in today's age of [[religious freedom]], the right to change one's religious conviction and leave the faith one was born into or chose is considered fundamental. The [[United Nations]], in its [[Universal Declaration of Human Rights]], Article 18, strongly affirmed the right of a person to change his religion: |

| − | | |

| − | During the [[Spanish inquisition]], a systematic conversion of Jews to Christianity took place, some of which under threats and force. These cases of apostasy provoked the indignation of the Jewish communities in Spain.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Several notorious Inquisitors, such as Juan [[Torquemada]], and Don Francisco the archbishop of [[Coria]], were descendants of apostate Jews. Other apostates who made their mark in history by attempting the conversion of other Jews in the 1300s include [[Juan de Valladolid]] and [[Astruc Remoch]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | However, the issue of what qualifies as "apostasy" in Judaism can be complicated, since in many modern movements in Judaism, rabbis have generally considered the behavior of a Jew to be the determining factor in whether or not one is considered an adherent or an apostate of Judaism. Within these movements it is often recognized that it is possible for a Jew to strictly practise [[Judaism]] as a faith, while at the same time being an agnostic or atheist, giving rise to the riddle: "Q: What do you call a Jew who doesn't believe in God? A: A Jew." It is also worth noting that [[Reconstructionist Judaism|Reconstructionism]] does not require any belief in a deity, and that certain popular [[Reform Judaism|Reform]] prayer books such as ''Gates of Prayer'' offer some services without mention of God.

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Abraham Isaac Kook]],<ref>http://www.vbm-torah.org/archive/rk16-kook.htm</ref><ref>http://www.vbm-torah.org/archive/rk17-kook.htm</ref> first Chief Rabbi of the Jewish community in then Palestine, held that atheists were not actually denying God: rather, they were denying one of man's many images of God. Since any man-made image of God can be considered an idol, Kook held that, in practice, one could consider atheists as helping true religion burn away false images of god, thus in the end serving the purpose of true monotheism.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==In Hinduism and Buddhism==

| |

| − | There is no concept of an apostate in Hinduism or Buddhism as there is no concept of conversion. Converts to other religions from Hinduism or Buddhism are accepted in these communities, as there is no Hindu or Buddhist procedure that defines apostasy.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==In alleged cults and new religious movements (NRMs)==

| |

| − | Some scholars of new religious movements define as apostates specifically those individuals that leave new religious movements and become public opponents against their former faith to distinguish them from other former members who do not speak against their former faith, while others contest such a distinction.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Some scholars use the term [[post-cult trauma]] to describe the emotional and social problems that some members of cults and new religious movements experience after leaving the group, while other scholars assert that such traumas are either only applicable in rare cases or are more likely caused by deprogramming or pre-existing psychological problems, not by voluntary leavetaking.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Some notable apostates are part of the secular [[opposition to cults and new religious movements]] or the [[Christian countercult movement]]. Some apostates of new religious movements make public stands against their former religion to warn the public of what they see as its dangers and harm. Several of those apostates maintain websites on their former groups with unflattering perspectives, testimonials and information which, they say, is not disclosed by those groups to the public. Critics like [[Basava Premanand]] complain about ''[[ad hominem]]'' attacks on them by their former organizations or by [[Apologetics|apologist]]s of their former faith, and claim that their goal is to provide information that enables current and prospective members to make an informed choice about joining or staying with a religious movement. Some of the groups being criticized, such as [[Adi Da|Adidam]]<ref>http://www.firmstand.org/articles/tolerance.html</ref> in turn, claim being the target of [[religious intolerance]], [[hate]] and ill-will by these critics.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Apostates of new religious movements make a number of allegations against their former affiliation and their leaders, including failed promises; [[sexual abuse]] by the leader who claimed to be pure and divine; false, [[irrational]] and contradictory teachings; [[deception]]; financial exploitation; demonizing of the outside world; abuse of power and [[hypocrisy]] of the leadership; discrimination; unnecessary secrecy; teaching platitudes; discouragement of [[critical thinking]]; [[brainwashing]]; [[mind control]]; [[exclusivism]]; [[pedophilia]]; leadership that does not admit any mistakes; and more.{{Fact|date=August 2007}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | === Opinions about the reliability of apostates' testimony and their motivations===

| |

| − | {{details|The Politics of Religious Apostasy}}

| |

| | | | |

| − | The validity of testimony by former members of new religious movements, their motivations, and the roles they play in the opposition to cults and new religious movements are controversial subjects among scholars of religion, sociologists and psychologists:

| + | <blockquote>Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, alone or in community with others, and, in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.</blockquote> |

| | | | |

| − | ;Beit-Hallahmi

| + | The UN [[Commission on Human Rights]] clarified that the recanting of a person's religion is a human right legally protected by the [[International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights]]: |

| − | *[[Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi]], a professor of psychology at the [[University of Haifa]], argues that academic supporters of [[New religious movements]] are engaged in a rhetoric of advocacy, apologetics and propaganda, and writes that in the cases of cult catastrophes such as [[Peoples Temple]], or [[Heaven's Gate (cult)|Heaven's Gate]], accounts by hostile outsiders and detractors have been closer to reality than other accounts, and that in that context statements by ex-members turned out to be more accurate than those of offered by apologists and NRM researchers.<ref>Beit-Hallahmi 1997 [[Benjamin Beith-Hallahmi|Beith-Hallahmi, Benjamin]] ''Dear Colleagues: Integrity and Suspicion in NRM Research'', 1997, [http://www.apologeticsindex.org/c59.htm]</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | ;Bromley and Shupe

| + | <blockquote>The Committee observes that the freedom to "have or to adopt" a religion or belief necessarily entails the freedom to choose a religion or belief, including the right to replace one's current religion or belief with another or to adopt atheistic views […] Article 18.2 bars coercion that would impair the right to have or adopt a religion or belief, including the use of threat of physical force or penal sanctions to compel believers or non-believers to adhere to their religious beliefs and congregations, to recant their religion or belief or to convert.<ref>CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.4, General Comment No. 22., 1993.</ref></blockquote> |

| − | *Bromley and Shupe while discussing the role of anecdotal [[atrocity story|atrocity stories]] by apostates, proposes that these are likely to paint a caricature of the group, shaped by the apostate's current role rather than his experience in the group, and question's their motives and rationale. Lewis Carter and [[David G. Bromley]] claim in some studies that the onus of pathology experienced by former members of new religions movements should be shifted from these groups to the coercive activities of the anti-cult movement.<ref>[[David G. Bromley|Bromley David G.]] et al., ''The Role of Anecdotal Atrocities in the Social Construction of Evil,''</ref><ref>in Bromley, David G et al. (ed.), ''Brainwashing Deprogramming Controversy: Sociological, Psychological, Legal, and Historical Perspectives (Studies in religion and society)'' p. 156, 1984, ISBN 0-88946-868-0</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | ;Charles

| + | Apostasy has, thus, come full circle. Once considered a crime against God worthy of the death penalty, in today's world, to renounce one's religion is a basic human right. In some nations, such as the [[United States]], this right is affirmed to be endowed to each of person by none other than God Himself. |

| − | *Dr. Phillip Charles Lucas<ref>http://www.culticstudiesreview.org/csr_profiles/indiv/lucas_phillip.htm</ref> interviewed ex-members of the [http://www.holyorderofmans.org/ Holy order of MANS/Christ the Savior Brotherhood] and compared them with stayers, and outside observers and came to the conclusion that their testimonies are as (un-)reliable as those of stayers.<ref>Lucas 1995 Lucas, Phillip Charles, ''From Holy Order of MANS to Christ the Savior Brotherhood: The Radical Transformation of an Esoteric Christian Order'' in Timothy Miller (ed.), ''America's Alternative Religions'' State University of New York Press, 1995</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | ;Duhaime

| + | ==Notes== |

| − | *Jean Duhaime, a professor of [[religious studies]] and science of religion at the [[Université de Montréal]] writes, based upon his analysis of three memoirs by apostates of NRMs (by Dubreuil, Huguenin, Lavallée, see bibliography), that he is more balanced than some researchers, referring to Wilson, and that apostate testimonies cannot be dismissed, only because they are not objective, though he admits that they write [[atrocity story|atrocity stories]] in the definition by Bromley and Shupe. He asserts that the reasons why they tell their stories are, among others, to warn others to be careful in religious matters and to put order in their own lives.<ref name="Duhaime 2003">Duhaime, Jean (Université de Montréal) ''Les Témoignages de convertis et d'ex-adeptes'' (English: ''The testimonies of converts and former followers'', in Mikael Rothstein et al. (ed.), ''New Religions in a Postmodern World'', 2003, ISBN 87-7288-748-6</ref>

| + | <references/> |

| − | | |

| − | ;Dunlop

| |

| − | *Mark Dunlop, a former member of [[FWBO]], argues that ex-members of cultic groups face great obstacles in exposing abuses committed by these groups, stating that ex-members "have great difficulty in disproving [[ad hominem]] arguments, such as that they have a personal axe to grind, that they are trying to find a scapegoat to excuse their own failure or deficiency [...] Cults have a vested interest in challenging the personal credibility of their critics, and may cultivate academic researchers who attack the credibility and motives of ex-members." Dunlop further expands on the specific difficulties faced by ex-members in proving harms done to them: "If an ex-member claims that they were subjected to brainwashing or mind-control techniques, not only is this again unprovable, but in the mind of the general public, it is tantamount to admitting that they are a gullible and easily led person whose opinions, consequently, can't be worth much. If an ex-member suffers from any mental disorientation or evident psychiatric symptoms, this is likely to further diminish their credibility as a reliable informant." He concludes with "In general, the public credibility of critical ex-cultists seems to be somewhere in between that of Estate Agents and flying saucer abductees." In the article's summary [http://www.ex-cult.org/fwbo/CofC.htm#advantages], Dunlop argues that given that the apostates' testimony is ineffective due to lack of public credibility, and that other forms of criticism are also ineffectual for various reasons, cults are virtually immune from outside criticism making it very difficult to expose cults.<ref>Dunlop 2001</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ;Introvigne

| |

| − | *[[Massimo Introvigne]] in his ''Defectors, Ordinary Leavetakers and Apostates''<ref>Introvigne 1997</ref> defines three types of [[narrative]]s constructed by apostates of new religious movements:

| |

| − | **Type I naratives: characterize the exit process as defection, in which the organization and the former member negotiate an exiting process aimed at minimizing the damage for both parties.

| |

| − | **Type II naratives: involve a minimal degree of negotiation between the exiting member, the organization it intends to leave, and the environment or society at large, impliying that the ordinary apostate holds no strong feelings concerning his past experience in the group.

| |

| − | **Type III naratives: characterized by the ex-member dramatically reversing his loyalties and becomes a [[professional]] enemy of the organization he has left. These apostates, often join an oppositional coalition fighting the organization, often claiming victimization.

| |

| − | :Introvigne argues that apostates professing ''type II'' narratives prevail among exiting members of controversial groups or organizations, while apostates that profess ''type III'' narratives are a vociferous minority.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ;Kliever

| |

| − | *Dr. [[Lonnie D. Kliever]] (1932 - 2004), Professor of Religious Studies of the [[Southern Methodist University]], in his paper titled ''The Reliability of Apostate testimony about New Religious movements'' that he wrote upon request for [[Scientology]], claims that the overwhelming majority of people who disengage from non-conforming religions harbor no lasting ill-will toward their past religious associations and activities, and that by contrast there is a much smaller number of apostates who are deeply invested and engaged in discrediting and performing actions designed to destroying the religious communities that once claimed their loyalties. He asserts that these dedicated opponents present a distorted view of the new religions and cannot be regarded as reliable informants by responsible journalists, scholars, or jurists. He claims that the reason for the lack of reliability of apostates is due to the [[psychological trauma|traumatic]] nature of disaffiliation that he compares to a [[divorce]] and also due the influence of the [[anti-cult movement]] even on those apostates who were not [[deprogramming|deprogrammed]] or received [[exit counseling]].<ref>Kliever 1995 Kliever. Lonnie D, Ph.D. ''The Reliability of Apostate Testimony About New Religious Movements'', 1995. [http://www.neuereligion.de/ENG/Kliever/start.htm]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ;Langone

| |

| − | *[[Michael Langone]] argues that some will accept uncritically the positive reports of current members without calling such reports, for example, "benevolence tales" or "personal growth tales." He asserts that only the critical reports of ex-members are called "tales," which he considers to be a term that clearly implies falsehood or fiction. He states that it wasn't until 1996 that a researcher conducted a study (Zablocki, 1996) to assess the extent to which so called "atrocity tales" might be based on fact.<ref>[http://www.culticstudiesreview.org/csr_articles/langone_michael_full.htm ''The Two "Camps" of Cultic Studies: Time for a Dialogue''] Langone, Michael, ''Cults and Society'', Vol. 1, No. 1, 2001 </ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ;Melton

| |

| − | *[[Gordon Melton]], while testifying as an expert witness in a lawsuit, said that when investigating groups, one should not rely solely upon the unverified testimony of ex-members, and that hostile ex-members would invariably shade the truth and blow out of proportion minor incidents turning them into major incidents.<ref>http://www.hightruth.com/experts/melton.html</ref> Melton also follows the argumentation of Lewis Carter and David Bromley above and claims that as a result of this study, the treatment (coerced or voluntary) of former members as people in need of psychological assistance largely ceased and that an (alleged) lack of widespread need for psychological help by former members of new religions would in itself be the strongest evidence refuting early sweeping condemnations of new religions as causes of psychological trauma.<ref>"Melton 1999"[[Gordon J. Melton|Melton, Gordon J.]], ''Brainwashing and the Cults: The Rise and Fall of a Theory'', 1999. [http://www.cesnur.org/testi/melton.htm]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ;Wilson

| |

| − | *[[Bryan R. Wilson]], who was a professor of Sociology at [[Oxford University]], writes that apostates of new religious movements, are generally in need of self-justification, seeking to reconstruct their own past and to excuse their former affiliations, while blaming those who were formerly their closest associates. Wilson utilizes the term of [[atrocity story]] that is in his view rehearsed by the apostate to explain how, by manipulation, coercion or deceit, he was recruited to a group that he now condemns.<ref name="Wilson 1981">[[Brian R. Wilson|Wilson, Bryan R.]] (Ed.) ''The Social Dimensions of Sectarianism'', Rose of Sharon Press, 1981.</ref> Wilson also challenges the reliability of the apostate's testimony by saying that "[apostates] always be seen as one whose personal history predisposes him to bias with respect to both his previous religious commitment and affiliations, the suspicion must arise that he acts from a personal motivation to vindicate himself and to regain his self-esteem, by showing himself to have been first a victim but subsequently to have become a redeemed crusader."<ref name="Wilson 1994">Wilson, Bryan R. ''Apostates and New Religious Movements'', Oxford, England, 1994</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ; Wright

| |

| − | * [[Stuart A. Wright]] explores the distinction between the apostate narrative and the role of the apostate, asserting that the former follows a predictable pattern, in which the apostate utilizes a "[[captivity narrative]]" that emphasizes manipulation, entrapment and being victims of "sinister cult practices." These narratives provide a rationale for a "hostage-rescue" motif, in which cults are likened to POW camps and deprogramming as heroic hostage rescue efforts. He also makes a distinction between "leavetakers" and "apostates," asserting that despite the popular literature and lurid media accounts of stories of "rescued or recovering 'ex-cultists'," empirical studies of defectors from NRMs "generally indicate favorable, sympathetic or at the very least mixed responses toward their former group." <ref> Wright, Stuart, A., '' Exploring Factors that Shatpe the Apostate Role'', in Bromley, David G., ''The Politics of Religious Apostasy'', pp. 95-114, Praeger Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0-275-95508-7</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ;Zablocki

| |

| − | * Professor [[Benjamin Zablocki]],<ref>http://www.rci.rutgers.edu/~zablocki/</ref> when analyzing leaver responses, found the testimonies of former members as least as reliable as statements from the groups themselves.<ref>Zablocki 1996 Zablocki, Benjamin, ''Reliability and validity of apostate accounts in the study of religious communities''. Paper presented at the Association for the Sociology of Religion in New York City, Saturday, August 17, 1996.</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Other uses of the term==

| |

| − | In popular usage, religious terminology like "apostasy" is often appropriated for use within other public spheres characterized by strongly-held beliefs, like [[politics]]. Such usage typically carries a much less negative connotation than the religious usage does, and sometimes people will even describe themselves as apostates. Authors [[Kevin Phillips (political commentator)|Kevin Phillips]] (a former [[United States Republican Party|Republican]] strategist turned harsh critic of the [[George W. Bush|Bush]] administration) and [[Christopher Hitchens]] (a former [[left-wing]] commentator turned enthusiastic supporter of the [[Iraq War]]) are examples of people who are often described as political apostates.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Noted apostates== | |

| − | This is a list of some notable persons that have been labeled an apostate by reliable published sources.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Christianity===

| |

| − | *[[Julian the Apostate]] ex-Christian and [[Roman emperor]]

| |

| − | *[[Maria Monk]] sometimes considered an apostate of the [[Roman Catholic church|Catholic Church]], though there is little evidence that she ever was a [[Roman Catholic|Catholic]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Islam===

| |

| − | *[[Ayaan Hirsi Ali]] labelled an apostate by [[Theo van Gogh (film director)|Theo van Gogh]] according to Ayaan Hirsi Ali<ref>[http://www.nos.nl/nieuws/achtergronden/theovangogh/openbriefhirsiali.html] Open letter by [[Ayaan Hirsi Ali]] published on the website of the [[Nederlandse Omroep Stichting]] dated 3 November 2004 <br/>English translation: "Theo's naivety was not it could not happen here, but that it could not happen to him. He said, "I am the village fool who is not harmed. But you have to be careful. You are the apostate woman"" <br/>Dutch original "Theo's naïviteit was niet dat het hier niet kon gebeuren, maar dat het hem niet kon gebeuren. Hij zei: "Ik ben de dorpsgek, die doen ze niets. Wees jij voorzichtig, jij bent de afvallige vrouw." "</ref>

| |

| − | * [[Salman Rushdie]] was accused of being an apostate of Islam by [[Ruhollah Khomeini]] due to the publication of his book [[The Satanic Verses (novel)|The Satanic Verses]]

| |

| − | * [[Tasleema Nasreen]], from Bangladesh, author of ''Lajja'' is wanted for defaming the name of Islam in Bangladesh

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Judaism===

| |

| − | * [[Tiberius Julius Alexander]], [[1st century]] Roman governor and general

| |

| − | * [[Baruch de Spinoza]], a 17th century Dutch philosopher of Portuguese Jewish origin

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==See also==

| |

| − | * [[Religious conversion]]

| |

| − | * [[Religious intolerance]]

| |

| − | * [[Excommunication]]

| |

| − | * [[Defection]]

| |

| − | * [[Faith Freedom International]]

| |

| − | * [[Religious disaffiliation]]

| |

| − | * [[Apostata capiendo]]

| |

| − | * [[Mutaween]]

| |

| − | * [[Backslide]]

| |

| | | | |

| | ==References== | | ==References== |

| − | <!-- ----------------------------------------------------------

| + | * Babinski, Edward (ed.). ''Leaving the Fold: Testimonies of Former Fundamentalists''. Prometheus Books, 2003. ISBN 1591022177 |

| − | See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Footnotes for a

| + | * Bromley, David G. et al. (ed.). ''Brainwashing Deprogramming Controversy: Sociological, Psychological, Legal, and Historical Perspectives (Studies in Religion and Society).'' Edwin Mellen Press, 1984. ISBN 0889468680 |

| − | discussion of different citation methods and how to generate

| + | * Bromley, David G. ''The Politics of Religious Apostasy: The Role of Apostates in the Transformation of Religious Movements.'' Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0275955087 |

| − | footnotes using the <ref>, </ref> and <reference /> tags

| + | * Elwell, Walter A. (ed.). ''Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible, Volume 1 A-I.'' Baker Book House, 1988. ISBN 0801034477 |

| − | ----------------------------------------------------------- —>

| + | * Lavallée, G. ''L'alliance de la brebis. Rescapée de la secte de Moïse.'' Montréal: Club Québec Loisirs, 1994. |

| − | {{reflist|2}}

| + | * Lucas, Phillip. ''NRMs in the 21st Century: Legal, Political, and Social Challenges in Global Perspective.'' 2004. ISBN 0415965772 |

| − | | + | * Wilson, S.G. ''Leaving the Fold: Apostates and Defectors in Antiquity''. Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 2004. ISBN 0800636759 |

| − | * Dunlop, Mark, ''The culture of Cults'', 2001 [http://www.fwbo-files.com/CofC.htm]

| + | * Wright, Stuart. "Post-Involvement Attitudes of Voluntary Defectors from Controversial New Religious Movements." ''Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 23'' (1984): 172-82. |

| − | * [[Massimo Introvigne|Introvigne, Massimo]] ''Defectors, Ordinary Leavetakers and Apostates: A Quantitative Study of Former Members of New Acropolis in France'' - paper delivered at the 1997 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Religion, San Francisco, November 23, 1997 [http://www.cesnur.org/testi/Acropolis.htm] | |

| − | * The Jewish Encyclopedia (1906). The Kopelman Foundation. [http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com]

| |

| − | * Lucas, Phillip Charles, ''The Odyssey of a New Religion: [[The Holy Order of MANS]] from New Age to Orthodoxy'' Indiana University press; | |

| − | * Lucas, Phillip Charles, ''Shifting Millennial Visions in New Religious Movements: The case of the Holy Order of MANS'' in ''The year 2000: Essays on the End'' edited by Charles B. Strozier, New York University Press 1997;

| |

| − | * Lucas, Phillip Charles, ''The Eleventh Commandment Fellowship: A New Religious Movement Confronts the Ecological Crisis'', Journal of Contemporary Religion 10:3, 1995:229-41; | |

| − | * Lucas, Phillip Charles, ''Social factors in the Failure of New Religious Movements: A Case Study Using Stark's Success Model'' SYZYGY: Journal of Alternative Religion and Culture 1:1, Winter 1992:39-53 | |

| − | * Zablocki, Benjamin et al., ''Research on NRMs in the Post-9/11 World'', in Lucas, Phillip Charles et al. (ed.), ''NRMs in the 21st Century: legal, political, and social challenges in global perspective'', 2004, ISBN 0-415-96577-2 | |

| − | * {{1911}} | |

| − | * Apostates of Islam, why Islam should be avoided [http://www.apostatesofislam.com]

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==Bibliography== | + | ==External Links== |

| − | ===Testimonies, memoirs, and autobiographies===

| + | All links retrieved August 11, 2023. |

| − | *Babinski, Edward (editor), ''Leaving the Fold: Testimonies of Former Fundamentalists''. Prometheus Books, 2003. ISBN-10: 1591022177; ISBN-13: 978-1591022176

| |

| − | *Dubreuil, J. P. 1994 ''L'Église de Scientology. Facile d'y entrer, difficile d'en sortir''. Sherbrooke: private edition (ex-[[Church of Scientology]])

| |

| − | *Huguenin, T. 1995 ''Le 54<sup>e</sup>'' Paris Fixot (ex-[[Ordre du Temple Solaire]] who would be the 54th victim)

| |

| − | * Kaufmann, ''Inside Scientology/Dianetics: How I Joined Dianetics/Scientology and Became Superhuman'', 1995 [http://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/Web/People/dst/Library/Shelf/kaufman/isd/isd.htm]

| |

| − | *Lavallée, G. 1994 ''L'alliance de la brebis. Rescapée de la secte de Moïse'', Montréal: Club Québec Loisirs (ex-[[Roch Theriault]])

| |

| − | * Pignotti, Monica, '' My nine lives in Scientology'', 1989, [http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~dst/Library/Shelf/pignotti/]

| |

| − | * Wakefield, Margery, ''Testimony'', 1996 [http://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/Web/People/dst/Library/Shelf/wakefield/testimony.html]

| |

| − | * Lawrence Woodcraft, Astra Woodcraft, Zoe Woodcraft, ''The Woodcraft Family'', Video Interviews [http://www.xenutv.com/interviews/woodcrafts.htm]

| |

| | | | |

| − | ===Writings by others ===

| + | * Introvigne, Massimo. [http://www.cesnur.org/testi/Acropolis.htm "Defectors, Ordinary Leavetakers and Apostates: A Quantitative Study of Former Members of New Acropolis in France"] - paper delivered at the 1997 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Religion, San Francisco, November 23, 1997. ''www.cesnur.org''. |

| − | *Bromley, David G. (Ed.) ''[[The Politics of Religious Apostasy|The Politics of Religious Apostasy: The Role of Apostates in the Transformation of Religious Movements]]'' CT, Praeger Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0-275-95508-7 | + | *Pignotti, Monica. [http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~dst/Library/Shelf/pignotti/ "My nine lives in Scientology"], 1989. ''www.cs.cmu.edu''. |

| − | *Carter, Lewis, F. Lewis, ''Carriers of Tales: On Assessing Credibility of Apostate and Other Outsider Accounts of Religious Practices'' published in the book ''The Politics of Religious Apostasy: The Role of Apostates in the Transformation of Religious Movements'' edited by David G. Bromley Westport, CT, Praeger Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0-275-95508-7

| + | * Wakefield, Margery. [http://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/Web/People/dst/Library/Shelf/wakefield/testimony.html "Testimony"], 1996. ''www.cs.cmu.edu''. |

| − | *Elwell, Walter A. (Ed.) ''Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible, Volume 1 A-I'', Baker Book House, 1988, pages 130-131, "Apostasy." ISBN 0801034477

| + | *[http://apostasyandislam.blogspot.com Islam and Apostasy]. ''apostasyandislam.blogspot.com''. Islam's affirmation of the Freedom of Faith and Freedom of Changing one's Faith. |

| − | * Malinoski, Peter, ''Thoughts on Conducting Research with Former Cult Members '', Cultic Studies Review, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2001 [http://www.culticstudiesreview.com/csr_articles/malinoski_peter.htm] | + | * Kaufmann, Robert. [http://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/Web/People/dst/Library/Shelf/kaufman/isd/isd.htm "Inside Scientology/Dianetics: How I Joined Dianetics/Scientology and Became Superhuman"], 1995. ''www.cs.cmu.edu''. |

| − | *Palmer, Susan J. ''Apostates and their Role in the Construction of Grievance Claims against the Northeast Kingdom/Messianic Communities'' [http://www.12tribes.org/controversies/apostatesandtheirrole.html]

| |

| − | * Wilson, S.G., ''Leaving the Fold: Apostates and Defectors in Antiquity''. Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 2004. ISBN-10: 0800636759; ISBN-13: 978-0800636753

| |

| − | * Wright, Stuart. ''Post-Involvement Attitudes of Voluntary Defectors from Controversial New Religious Movements''. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 23 (1984): pp. 172-82

| |

| | | | |

| − | {{wiktionarypar|apostasy}}

| |

| − | <!--==External links==

| |

| − | *[http://apostasyandislam.blogspot.com Islam and Apostasy] Islam's affirmation of the Freedom of Faith and Freedom of Changing one's Faith

| |

| − | * [http://www.alislam.org/books/apostacy/index.html The punishment of Apostasy in Islam]

| |

| − | *[http://www.globalwebpost.com/farooqm/writings/islamic/apostasy_dawah.doc Apostasy, Freedom and Da’wah: Full Disclosure in a Business-like Manner] by Dr. Mohammad Omar Farooq

| |

| − | * [http://www.real-islam.org/audio/zakir_apostate.wmv World's #1 Muslim Debator advocates Capital Punishment for Apostates - Watch brief video]

| |

| − | * [http://www.real-islam.org/audio/defeatvideo.ram Another known Muslim Scholar advocates Capital Punishment for Apostates - Watch brief video]

| |

| − | * [http://www.real-islam.org/audio/murtad.wmv A video on "Apostasy & Holy Quran]

| |

| − | * [http://www.backtoislam.com Back To Islam - Stories of ex-apostates of Islam]

| |

| − | * [http://www.islamonline.net/fatwa/english/FatwaDisplay.asp?hFatwaID=117869 Fatwa, Islam & freedom]

| |

| − | * [http://www.religioustolerance.org/isl_apos.htm APOSTASY (IRTIDÃD) IN ISLAM: The act in which a Muslim abandons Islam]

| |

| − | * [http://www.answering-christianity.com/apostates.htm Apostasy in Islam]

| |

| − | * [http://www.sunna.info/Lessons/islam_333.html Apostasy From Islam]

| |

| − | *[http://www.ex-christian.net/ ex-christian.net]

| |

| − | *[http://www.exchristian.org/ exchristian.org]

| |

| − | *[http://www.christianism.com/ christianism.com]

| |

| − | * [http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01624b.htm Catholic Encyclopedia] see Apostasy a Fide

| |

| − | *[http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/jim_meritt/bible-contradictions.html A list of apparent contradictions to be found if reading the 'Bible' as a literal and clear statement of fact]

| |

| − | *[http://www.equip.org/free/JAW220.htm Witnessing to Those Who Have Fallen From Faith] J.P. Holding

| |

| − | * [http://www.apostazja.info/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=116&Itemid=50 Information on a proposed procedure and the consequences of formally renouncing the Faith of the Catholic Church]

| |

| − | * [http://www.kelebekler.com/cesnur/eng.htm The CESNUR case] website of Miguel Martinez, a critical former member of [[New Acropolis]], who criticizes [[Massimo Introvigne]]'s study of ex-members of New Acropolis and the assertions made by [[Bryan R. Wilson]] about apostates

| |

| − | * [http://endtimepilgrim.org/apostasy.htm The Great Apostasy at the end of the age] — Helpful quotes from article include: "He will establish his 666 economic system based on some sort of blood covenant marking of citizens. This will be the ultimate apostasy."

| |

| − | * [http://www.faithfreedom.org/testimonials.htm More Apostasy from Islam]

| |

| | | | |

| | [[Category:philosophy and religion]] | | [[Category:philosophy and religion]] |

| | {{Credit|150790132}} | | {{Credit|150790132}} |

Apostasy is the formal renunciation of one's religion. One who commits apostasy is called an apostate. Many religious faiths consider apostasy to be a serious sin. In some religions, an apostate will be excommunicated or shunned, while in certain Islamic countries today, apostasy is punishable by death. Historically, both Judaism and Christianity harshly punished apostasy as well, while the non-Abrahamic religions tend to deal with apostasy less strictly.

Apostasy is distinguished from heresy in that the latter refers to the corruption of specific religious doctrines but is not a complete abandonment of one's faith. However, heretics are often declared to be apostates by their original religion. In some cases, heresy has been considered a more serious sin or crime than apostasy, while in others the reverse is true.

When used by sociologists, apostasy often refers to both renunciation and public criticism of one's former religion. Sociologists sometimes make a distinction between apostasy and "defection," which does not involve public opposition to one's former religion.

Apostasy, as an act of religious conscience, has acquired a protected legal status in international law by the United Nations, which affirms the right to change one's religion or belief under Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Apostasy in the Abrahamic religions

Judaism

In the Hebrew Bible, apostasy is equated with rebellion against God, His Law, and and worshiping any god other than the Hebrew deity, Yahweh. The penalty for apostasy in Deuteronomy 13:1-10 is death.

That prophet or that dreamer (who leads you to worship of other gods) shall be put to death, because… he has preached apostasy from The Lord your God… If your own full brother, or your son or daughter, or your beloved wife, or your intimate friend, entices you secretly to serve other gods… do not yield to him or listen to him, nor look with pity upon him, to spare or shield him, but kill him… You shall stone him to death, because he sought to lead you astray from the Lord, your God.