Apache

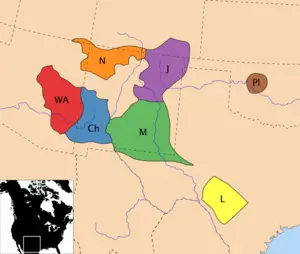

Apache is the collective name for several culturally related groups of Native Americans in the United States, aboriginal inhabitants of North America, who speak a Southern Athabaskan (Apachean) language. The modern term excludes the related Navajo people. However, the Navajo and the other Apache groups are clearly related through culture and language and thus are considered Apachean. Apachean peoples formerly ranged over eastern Arizona, north-western Mexico, New Mexico, parts of Texas, and a small group on the plains.

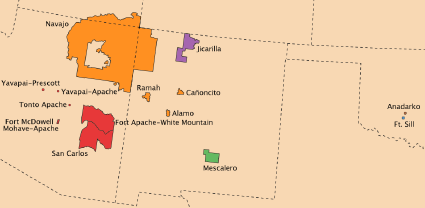

There was little political unity among the Apachean groups. The groups spoke 7 different languages. The current division of Apachean groups includes the Navajo, Western Apache, Chiricahua, Mescalero, Jicarilla, Lipan, and Plains Apache (formerly Kiowa-Apache). Apache groups are now in Oklahoma and Texas and on reservations in Arizona and New Mexico. The Navajo reside on a large reservation in the United States. Some Apacheans have moved to large metropolitan areas, such as New York City.

The Apachean tribes were historically very powerful, constantly at enmity with the whites for centuries. The U.S. Army, in their various confrontations, found them to be fierce warriors and skillful strategists.

Name and synonymy

Name

The name Apache was borrowed into English via Spanish and the ultimate origin is uncertain. The first known written record in Spanish is by Juan de Oñate in 1598. The most widely accepted origin theory suggests it was borrowed from the Zuni word ʔa·paču that refers to "Navajos." It is interesting to note that modern Zuni words identify Apache groups such as wilacʔu·kwe "White Mountain Apache" and čišše·kʷe "San Carlos Apache, Apaches in general") and have this one word for the Navajo. Another theory suggests the term comes from Yavapai ʔpačə meaning "people." It is likely that Oñate did not use the name in Spanish for the first time because several Spanish groups had contact with Zuni pueblos in 1539-41. Other possible origins may be from Spanish mapache "raccoon" and from an unspecified Quechan word meaning "running warrior horse."

The Spanish first use the term "Apachu de Nabajo" (Navajo) in the 1620s, referring to people in the Chama region east of the San Juan River. By the 1640s, the term was applied to Southern Athabaskan peoples from the Chama on the east to the San Juan on the west.

The tribes tenacity and fighting skills, probably bolstered by dime novels, had an impact on Europeans. In early twentieth century Parisian society Apache essentially meant an outlaw.

Synonymy

This section will attempt to create a list of synonyms or names that have been applied to Apacheans speakers in the Southwest by multiple cultures over a long period of time.

Difficulties in naming

Many written historical names of Apachean groups recorded by non-Apacheans are difficult to match to modern-day tribes or their sub groups. Many Spanish, French or English speaking authors over the centuries did not distinguish between Apachean and other semi-nomadic non-Apachean peoples that might pass through the same area. More commonly a name was acquired through a translation of what another group called them. While Anthropologists seem to agree on some traditional major sub grouping of Apaches, they often have used different criterion to name their finer divisions and these do not always match modern Apache groupings. Often groups residing in what is now Mexico are not considered Apaches by some. Adding to an outsider's confusion, an Apachean individual has different ways to identify themselves, such as their band or their clans, depending upon the context.

For example: Grenville Goodwin in the 1930's divided the Western Apaches into five groups: White Mountain, Cibecue, San Carlos, North Tonto, and South Tonto. Other anthropologists consider Goodwin's classification inconsisent with pre-reservation cultural divisions. Willem de Reuse (2003, 2005, 2006) finds linguistic evidence supporting three major groupings: White Mountain, San Carlos, and Dilze’eh (Tonto) with San Carlos as the most divergent dialect and Dilze’eh as a remnant intermediate member of a dialect continuum previously existing between the Western Apache language and Navajo.

John Upton Terrell divides the Apaches into Western and Eastern groups. In the western group he includes Toboso, Cholome, Jocome, Sibolo, Pelone, Manso as having definite Apache connections or names associated with Apaches by the Spanish.

David M. Brugge in a detailed study of New Mexico Church records lists 15 tribal names Spanish used that refer Apaches that represent about 1000 baptisms from 1704 to 1862.

List of names

- Apaches, current usage generally includes 6 of the 7 major traditional Apachean speaking groups: Chiricahua, Jicarilla, Lipans, Mescalero, Plains Apache, and Western.

- Arivaipa (also Aravaipa) is a band of the San Carlos local group of the Western Apache. Albert Schroeder believes the Arivaipa was a separate section in pre-reservation times. Arivaipa *is a borrowing (via Spanish) from the O'odham language. The Arivaipa are known as Tsézhiné "Black Rock" in the Western Apache language.

- Carlanas located in what is now Southeastern Colorado

- Chiricahua, Anthropologist consider Chiricahua as one of the 7 major Apachean groups, ranging in southeastern Arizona. See Chishi.

- Chíshí (also Tchishi) is a Navajo word meaning "Chiricahua, southern Apaches in general." A similar words occur in Jicarilla Chíshín and Lipan Chishį́į́hį́į́ "Forest Lipan."

- Chʼúúkʼanén (also Čʼókʼánéń, Čʼó·kʼanén, Chokonni, Cho-kon-nen, Cho Kŭnĕ́, Chokonen) refers to the Eastern Chiricahua band of Morris Opler. The name is an autonym from the Chiricahua language.

- Cibecue, A Western Apache group, living to the North of the Salt River between the Tontos and White Mountain groups according to Goodwin.

- Coyotero usually refers to a southern division of the pre-reservation White Mountain local group of the Western Apache. However, the name has also been used more widely and can refer to Apaches in general, Western Apaches or a band in the high plains of southern Colorado to Kansas.

- Faraones (also Paraonez, Pharaones, Taraones, Taracones, Apaches Faraone) is derived from Spanish Faraón "Pharaoh." Before 1700, the name was vague without a specific referent. Between 1720-1726, it referred to Apaches between the Rio Grande in the east, the Pecos River in the west, the area around Santa Fe in the north, and the Conchos River in the south. After 1726, Faraones only referred to the north and central parts of this region. The Faraones probably were, at least in part, part of the modern-day Mescaleros or had merged with the Mescaleros. After 1814, the term Faraones disappeared having been replaced by Mescalero.

- The Gileño (also Apaches de Gila, Apaches de Xila, Apaches de la Sierra de Gila, Xileños, Gilenas, Gilans, Gilanians, Gila Apache, Gilleños) was used to refer to several different Apachean and non-Apachean groups at different times. Gila refers to either the Gila River or the Gila Mountains. Some of the Gila Apaches were probably later known as the Mogollon Apaches, a subdivision of the Chiricahua, while others probably evolved into the Chiricahua proper. However, since the term was used indiscriminately for all Apachean groups west of the Rio Grande (i.e. in southeast Arizona and western New Mexico), the referent is often unclear. After 1722, Spanish documents start to distinguish between these different groups, in which case Apaches de Gila refers to Western Apaches living along the Gila River (and thus synonymous with Coyotero). American writers first used the term to refer to the Mimbres (another subdivision of the Chiricahua), while later the term was confusingly used to refer to Coyoteros, Mogollones, Tontos, Mimbreños, Pinaleños, Chiricahuas, as well as the non-Apachean Yavapai (then also known as Garroteros or Yabipais Gileños). Another Spanish usage (along with Pimas Gileños and Pimas Cileños) referred to the non-Apachean Pima living on the Gila River.

- Jicarilla or "little basket" in Spanish. The Jicarilla Apache are one of the 7 major Apachean groups and currently live in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado. Also referenced as living in Texas Panhandle.

- Kiowa. Traditionally the Plains Apache are one of the 7 major Apachean groups. They currently live in Oklahoma among the Kiowa who speak one of the Tanoan languages.

- Llanero is a borrowing from Spanish meaning "plains dweller." The name was historically used to refer to a number of different groups that hunted buffalo seasonally on the Plains, also referenced in eastern New Mexico and western Texas. (see also Carlanas)

- Lipiyánes

- Lipan, Natagés. The connections between these groups is not completely clear. Anthropologist consider Lipan Apache as one of the 7 major Apachean groups. Once in eastern New Mexico and Texas to the southeast to Gulf of Mexico.

- Mescalero. The Mescalero are one of the 7 major Apachean groups, generally living in what is now eastern New Mexico and western Texas.

- Mimbreños is an older name that refers to a section of Opler's Eastern Chiricahua band and to Albert Schroeder's Mimbres and Warm Springs Chiricahua bands (Oplers lists three Chircahua bands, while Schroeder lists five) in southwestern New Mexico.

- Mogollon was considered by Schroeder a separate pre-reservation Chiricahua band while Opler considered the Mogollon to be part of his Eastern Chiricahua band in New Mexico.

- Náʼįįsha (also Náʼęsha, Na´isha, Naʼisha, Naʼishandine, Na-i-shan-dina, Na-ishi, Na-e-ca, Nąʼishą́, Nadeicha, Nardichia, Nadíisha-déna, Naʼdíʼį́shą́ʼ, Nądíʼįįshąą, Naisha) all refer to the Plains Apache (see Kiowa).

- Natagés in eastern New Mexico and western Texas, a group associated with Lipans.

- Navajo. The most numerous of the 7 major Apachean groups. General modern usage separates Navajo people from Apaches.

- Pinaleños

- Plains Apache. The Plains Apache (also called Kiowa-Apache, Naisha, Naʼishandine, etc.) are one of the 7 major Apachean groups, generally living in what is now Oklahoma.

- Ramah. A group of Navajos (Navajo: Tłʼohchiní) currently living in the Ramah Navajo Indian Reservation.

- Querechos referred to by Coronado in 1541, possibly Plains Apaches, at times maybe Navajo. Other early Spanish might have also called them Vaquereo or Llanero.

- San Carlos. A Western Apache group that ranged closest to Tucson according to Goodwin.

- Tchikun

- Tonto, Goodwin divided into Northern Tonto and Southern Tonto groups. Living in the north and west most areas of the Western Apache groups according to Goodwin. This is north of Phoenix, north of the Verde River. Some have suggested that the Tonto are originally Yavapais who assimilated Western Apache culture. Tonto is one of the major dialects of the Western Apache language. Tonto Apache speakers are traditionally bilingual in Western Apache and Yavapai.

- Warm Springs were located on upper reaches of Gila River, New Mexico. (see also Gilians and Mimbreños)

- Western Apaches, includes Northern Tonto, Southern Tonto, Cibecue, White Mountain and San Carlos groups. While these sub groups spoke the same language and had kinship ties, Western Apaches considered themselves as separate from each other, according to Goodwin.

- ''White Mountain. The easternmost group of the Western Apache according to Goodwin.

History

Entry into the Southwest

The Apache and Navajo (Diné) tribal groups of the American Southwest speak related languages of the language family referred to as Athabaskan. Other Athabaskan speaking people in North America reside in an area from Alaska through west-central Canada, and some groups can be found along the Northwest Pacific Coast. Linguistic similarities indicate the Navajo and Apache were once a single ethnic group. Archaeological and historical evidence seem to suggests their entry into the American Southwest sometime after 1000 C.E., with a substaintial numbers and range recorded by the Spanish in the 16th Century.

There are several hypotheses concerning Apachean migrations. One posits that they moved into the Southwest from the Great Plains. In the early 1500s, these mobile groups lived in tents, hunted bison and other game, and used dogs to pull travois loaded with their possessions. In April 1541, while traveling on the plains east of the Pueblo region, the Spanish Francisco Coronado called them “dog nomads.” He wrote:

- After seventeen days of travel, I came upon a rancheria of the Indians who follow these cattle (bison). These natives are called Querechos. They do not cultivate the land, but eat raw meat and drink the blood of the cattle they kill. They dress in the skins of the cattle, with which all the people in this land clothe themselves, and they have very well-constructed tents, made with tanned and greased cowhides, in which they live and which they take along as they follow the cattle. They have dogs which they load to carry their tents, poles, and belongings. (See Hammond and Rey.)

The Spaniards described Plains dogs as very white, with black spots, and “not much larger than water spaniels.” Plains dogs were slightly smaller than those used for hauling loads by modern northern Canadian peoples. Recent experiments show these dogs may have pulled loads up to 50 lb (20 kg) on long trips, at rates as high as two or three miles an hour (3 to 5 km/h). (See Henderson.) This Plains migration theory associates Apachean peoples with the Dismal River aspect, an archaeological culture known primarily from ceramics and house remains, dated 1675-1725 excavated in Nebraska, eastern Colorado, and western Kansas.

Another competing theory posits a migration through the mountains ultimately reaching the Southwest. Only the Plains Apache have any significant Plains cultural influence while all tribes have distinct Athabaskan characteristics. The descriptions of peoples such as the Mountain Querechos and the Apache Vaqueros are vague and could apply to many other Plains tribes and the specific traits of these groups do not seem particularly Apachean. Additionally, Harry Hoijer's classification of Plains Apache as an Apachean language has been disputed.

There are several factors that complicate migration theories. The Southern Athabaskan nomadic way of life complicates accurate dating, primarily because they constructed less-substantial dwellings than other Southwestern groups. They also left behind a more austere set of tools and material goods. This group probably moved into areas that were concurrently or recently abandoned by other cultures. Other Athabaskan speakers, perhaps like the Souther Athabaskan, have adapted many of their neighbors practices in their own cultures. Thus sites where early Southern Athabaskans may have lived are difficult to locate, and even more difficult to firmly identify as culturally Southern Athabaskan.

When the Spanish arrived in the area, trade between the long established Pueblo peoples and the Southern Athabaskans was well established. They reported the Pueblos exchanged maize and woven cotton goods for bison meat, hides and materials for stone tools. As mentioned earlier, Coronado observed Plains people wintering near the Pueblos in established camps. He also reported in 1540 that the modern Western Apache area as uninhabited. Other Spaniards first mention "Querechos" living west of the Rio Grande in the 1580s. To some historians this means the Apaches moved into their current southwestern homelands in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Others historians note that Coronado reported that Pueblos women and children had often been evacuated by the time his party attacked these dwellings and sometimes they were recently abandoned as he moved up the Rio Grande. This might indicate the semi-nomadic Southern Athabaskans had advance warning about his hostile approach and one reason they were not reported by the Spanish.

Conflict with Mexico and the United States

In general, there seemed to be a pattern between the recently arrived Spanish who settled in villages and Apache bands over a few centuries. Both raided and traded with each other. Records of the period seem to indicate that relationships depended upon the specific villages and specific bands that were involved with each other. For example, one band might be friends with one village and raid another. When war happened between the two, the Spanish would send troops, after a battle both sides would "sign a treaty" and both sides would go home. There were no reservations.

The traditional and sometimes treachereous relationships continued between the villages and bands with the independence of Mexico in 1821. By 1835 Mexico had placed a bounty on Apache scalps but some bands were still trading with certain villages. When Juan José Compas, the leader of the Mimbreño Apaches, was killed for bounty money in 1837, Mangas Coloradas or Dasoda-hae (Red Sleeves) became principal chief and war leader and began a series of retaliatory raids against the Mexicans.

When the United States went to war against Mexico, many Apache bands promised U.S. soldiers safe passage through their lands. When the U.S. claimed former territories of Mexico in 1846, Mangas Coloradas signed a peace treaty, respecting them as conquerors of the Mexican's land. An uneasy peace (a centuries old tradition) between the Apache and the now citizens of the United States held until the 1850s, when an influx of gold miners into the Santa Rita Mountains led to conflict. This period is sometimes called the Apache Wars.

The United States' concept of a reservation had not been used by the Spanish, Mexicans or other Apache neighbors before. Reservations were often badly managed and bands who had no kinship relationships were forced to live together. There were also no fences to keep people in or out. It was not uncommon for a band to be given permission to leave for a short period of time. Other times a band would leave without permission, to raid, return to their land to forage or simply get away. The military usually had forts nearby and their job was keep the various bands on the reservations by finding and returning those who left. The reservation policies of the United States kept various Apache bands leaving the reservations (at war) for almost another quarter century.

Most American histories of this era say the final defeat of an Apache band took place when 5,000 troops forced (Geronimo's) group of 30 to 50 men, women and children to surrender in 1886. This band and the Chiricahua scouts who tracked them were all sent to military confinement in Florida, and, subsequently, Ft. Sill, Oklahoma.

Modern Apache groups

The major modern Apache groups include the Jicarilla and Mescalero of New Mexico, the Chiricahua of the Arizona-New Mexico border area, the Western Apache ofs Days celebration with a historic re-enactment and a pow wow.

Apache children were taken for adoption by white Americans in programs similar in nature to those involving the Stolen Generation of Australia.

Pre-reservation culture

Social organization

All Apachean peoples lived in extended family units (or family clusters) that usually lived close together with each nuclear family in separate dwellings. An extended family generally consisted of a husband and wife, their unmarried children, their married daughters, their married daughters' husbands, and their married daughters' children. Thus, the extended family is connected through a lineage of women that live together (that is, matrilocal residence), into which men may enter upon marriage (leaving behind his parents' family). When a daughter was married, a new dwelling was built nearby for her and her husband. Among the Navajo, residence rights are ultimately derived from a head mother. Although the Western Apache usually practiced matrilocal residence, sometimes the eldest son chose to bring his wife to live with his parents after marriage. All tribes practiced sororate and levirate marriages.

All Apachean men practiced varying degrees of avoidance of his wife's close relatives — often strictest between mother-in-law and son-in-law. The degree of avoidance differed in different Apachean groups. The most elaborate system was among the Chiricahua where men must use indirect polite speech toward and were not allowed to be within visual sight of his relatives that he was in an avoidance relationship with. His female Chiricahua relatives also did likewise to him.

Several extended families worked together as a local group, which carried out certain ceremonies, and economic and military activities. Political control was mostly present at the local group level. Local groups were headed by a chief, a male who had considerable influence over others in the group due to his effectiveness and reputation. The chief was the closest societal role to a leader in Apachean cultures. The office was not hereditary and often filled by members of different extended families. The chief's leadership was only as strong as he was evaluated to be — no group member was ever obliged to follow the chief. Many Apachean peoples joined together several local groups into bands. Band organization was strongest among the Chiricahua and Western Apache, while in the Lipan and Mescalero it was weak. The Navajo did not organize local groups into bands perhaps because of the requirements of the sheepherding economy. However, the Navajo did have the outfit, a group of relatives that was larger than the extended family, but not as large as a local group community or a band.

On the larger level, the Western Apache organized bands into what Grenville Goodwin called groups. He reported five groups for the Western Apache: Northern Tonto, Southern Tonto, Cibecue, San Carlos, and White Mountain. The Jicarilla grouped their bands into moieties perhaps due to influence from northeastern Pueblos. Additionally the Western Apache and Navajo had a system of matrilineal clans that were organized further into phratries (perhaps due to influence from western Pueblos). The notion of tribe in Apachean cultures is very weakly developed essentially being only a recognition of similar speech and culture. In fact, not all Apaches recognize the existence of tribes within their cultures. The seven Apachean tribes had no political unity and often were enemies of each other — for example, the Lipan fought against the Mescalero just as with the Comanche.

Kinship systems

The Apachean tribes have basically two surprisingly different kinship term systems: a Chiricahua type and a Jicarilla type (Opler 1936). The Chiricahua type system is used by the Chiricahua, Mescalero, and Western Apache with the Western Apache differing slightly from the other two systems and having some shared similarities with the Navajo system.

The Jicarilla type, which is similar to the Dakota-Iroquois kinship systems (see Iroquois kinship), is used by the Jicarilla, Navajo, Lipan, and Plains Apache. The Navajo system is more divergent having similarities with Chiricahua type system. The Lipan and Plains Apache systems are very similar.

(N.B. All kinship terms in Apachean languages are inherently possessed, which means they must be preceded by a possessive prefix. This is signified below by the preceding hyphen.)

Chiricahua

Chiricahua has four different words for grandparents: -chó "maternal grandmother",-tsóyé "maternal grandfather," -chʼiné "paternal grandmother," -nálé "paternal grandfather." Additionally, a grandparent's siblings are identified by the same word; thus, one's maternal grandmother, one's maternal grandmother's sisters, and one's maternal grandmother's brothers are all called -chó. Furthermore, the grandparent terms are reciprocal (i.e. same terms for alternating generations), that is, a grandparent will use the same term to refer to their grandchild in that relationship. For example, a person's maternal grandmother will be called -chó and that maternal grandmother will also call that person -chó as well (i.e. -chó means one's opposite-sex sibling's daughter's child).

Chiricahua cousins are not distinguished from siblings through kinship terms. Thus, the same word will refer to either a sibling or a cousin (there are not separate terms for parallel-cousin and cross-cousin). Additionally, the terms are used according to the sex of the speaker (unlike the English terms brother and sister): -kʼis "same-sex sibling or same-sex cousin," -´-ląh "opposite-sex sibling or opposite-sex cousin." This means if one is a male, then one's brother is called -kʼis and one's sister is called -´-ląh. If one is a female, then one's brother is called -´-ląh and one's sister is called -kʼis. Chiricahuas in a -´-ląh relationship observed great restraint and respect toward that relative; cousins (but not siblings) in a -´-ląh relationship may practice total avoidance.

Two different words are used for each parent according to sex: -mááʼ "mother," -taa "father." Likewise, there are two words for a parent's child according to sex: -yáchʼeʼ "daughter," -gheʼ "son."

A parent's siblings are classified together regardless of sex: -ghóyé "maternal aunt or uncle (mother's brother or sister)," -deedééʼ "paternal aunt or uncle (father's brother or sister)." These two terms are reciprocal like the grandparent/grandchild terms. Thus, -ghóyé also refers to one's opposite-sex sibling's son or daughter (that is, a person will call their maternal aunt -ghóyé and that aunt will call them -ghóyé in return).

Jicarilla

Unlike the Chiricahua system, the Jicarilla have only two terms for grandparents according to sex: -chóó "grandmother," -tsóyéé "grandfather." There are no separate terms for maternal or paternal grandparents. The terms are also used of a grandparent's siblings according to sex. Thus, -chóó refers to one's grandmother or one's grandaunt (either maternal or paternal); -tsóyéé refers to one's grandfather or one's granduncle. These terms are not reciprocal. There is only a single word for grandchild (regardless of sex): -tsóyį́į́.

There two terms for each parent. These terms also refer to that parent's same-sex sibling: -ʼnííh "mother or maternal aunt (mother's sister)," -kaʼéé "father or paternal uncle (father's brother)." Additionally, there are two terms for a parent's opposite-sex sibling depending on sex: -daʼą́ą́ "maternal uncle (mother's brother)," -béjéé "paternal aunt (father's sister).

Two terms are used for same-sex and opposite-sex siblings. These terms are also used for parallel-cousins: -kʼisé "same-sex sibling or same-sex parallel cousin (i.e. same-sex father's brother's child or mother's sister's child)," -´-láh "opposite-sex sibling or opposite parallel cousin (i.e. opposite-sex father's brother's child or mother's sister's child)." These two terms can also be used for cross-cousins. There are also three sibling terms based on the age relative to the speaker: -ndádéé "older sister," -´-naʼą́ą́ "older brother," -shdą́zha "younger sibling (i.e. younger sister or brother)." Additionally, there are separate words for cross-cousins: -zeedń "cross-cousin (either same-sex or opposite-sex of speaker)," -iłnaaʼaash "male cross-cousin" (only used by male speakers).

A parent's child is classified with their same-sex sibling's or same-sex cousin's child: -zhácheʼe "daughter, same-sex sibling's daughter, same-sex cousin's daughter," -gheʼ "son, same-sex sibling's son, same-sex cousin's son." There are different words for an opposite-sex sibling's child: -daʼą́ą́ "opposite-sex sibling's daughter," -daʼ "opposite-sex sibling's son."

Housing

All people in the Apache tribe lived in one of three types of houses. the first of which is the tipi, for those who lived in the plains. Another type of housing is the wickiup, an eight foot tallframe of wood held together with yucca fibers and covered in brush usually in the Apache groups in the highlands. The final housing is the hogan, an earthen structure in the desert area that was good for keeping cool in the hot weather of northern Mexico.

Food

Apacheans obtained food from four main sources: hunting wild animals, gathering wild plants, growing domesticated plants, and interaction with neighboring peoples for livestock and agricultural products (through raiding or trading). The different Apachean groups varied greatly with respect to growing domesticated plants: some Chiricahua bands claim to have practiced no farming at all.

The Western Apache diet consisted of 35-40% meat and 60-65% plant foods.

As the different Apachean tribes lived in different environments, the particular types of foods eaten varied accrording to their respective environment.

Hunting was done primarily by men. The men hunted deer, antelope, and other big game.

Although not distinguished by Europeans or Euro-Americans, all Apachean tribes made clear distinctions between raiding (for profit) and war. Raiding was done with small parties with a specific economic target. Warfare was waged with large parties (often using clan members) with the sole purpose of retribution.

Languages

Apachean peoples speak one or more of seven Southern Athabascan languages, which have relatively similar grammatical structures and sound systems. Southern Athabascan (or Apachean) is sub-family of the larger Athabascan family (itself a branch of Na-dene).

Navajo is notable for being the indigenous language of the United States with the largest number of native speakers. However, all Apachean languages are endangered, including even Navajo. Lipan is reported extinct.

The Southern Athabascan branch was defined by Harry Hoijer primarily according to its merger of stem-initial consonants of the Proto-Athabascan series *k̯ and *c into *c (in addition to the widespread merger of *č and *čʷ into *č also found in many Northern Athabascan languages).

| Proto- Athabascan |

Navajo | Western Apache |

Chiricahua | Mescalero | Jicarilla | Lipan | Plains Apache | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *k̯uʔs | "handle fabric-like object" | -tsooz | -tsooz | -tsuuz | -tsuudz | -tsoos | -tsoos | -tsoos |

| *ce· | "stone" | tsé | tséé | tsé | tsé | tsé | tsí | tséé |

Hoijer (1938) divided the Apachean sub-family into an Eastern branch consisting of Jicarilla, Lipan, and Plains Apache and a Western branch consisting of Navajo, Western Apache (San Carlos), Chiricahua, and Mescalero based on the merger of Proto-Apachean *t and *k to k in the Eastern branch. Thus, as can be seen in the example below, when the Western languages have noun or verb stems that start with t, the related forms in the Eastern languages will start with a k:

Western Eastern Navajo Western

ApacheChiricahua Mescalero Jicarilla Lipan Plains

Apache"water" tó tū tú tú kó kó kóó "fire" kǫʼ kǫʼ kųų kų ko̱ʼ kǫǫʼ kǫʼ

He later revised his proposal in 1971 when he found that Plains Apache did not participate in the *k̯/*c merger to consider Plains Apache as a language equi-distant from the other languages, now called Southwestern Apachean. Thus, some stems that originally started with *k̯ in Proto-Athabascan start with ch in Plains Apache while the other languages start with ts.

Proto-

AthabascanNavajo Chiricahua Mescalero Jicarilla Plains

Apache*k̯aʔx̣ʷ "big" -tsaa -tsaa -tsaa -tsaa -cha

Morris Opler (1975) has suggested that Hoijer's original formulation that Jicarilla and Lipan in an Eastern branch was more in agreement with the cultural similarities between these two and the differences from the other Western Apachean groups. Other linguists, particularly Michael Krauss (1973), have noted that a classification based only on the initial consonants of noun and verb stems is arbitrary and when other sound correspondences are considered the relationships between the languages appear to be more complex. Additionally, it has been pointed out by Martin Huld (1983) that since Plains Apache does not merge Proto-Athabascan *k̯/*c, Plains Apache cannot be considered an Apachean language as defined by Hoijer.

Apachean languages are tonal languages. Regarding tonal development, all Apachean languages are low-marked languages, which means that stems with a "constricted" syllable rime developed low tone while all other rimes developed high tone. Other Northern Athabascan languages are high-marked languages in which the tonal development is the reverse. In the example below, if low-marked Navajo and Chiricahua have a low tone, then the high-marked Northern Athabascan languages, Slavey and Chilcotin, have a high tone, and if Navajo and Chiricahua have a high tone, then Slavey and Chilcotin have a low tone.

Low-Marked High-Marked Proto-

AthabascanNavajo Chiricahua Slavey Chilcotin *taʔ "father" -taaʼ -taa -táʔ -tá *tu· "water" tó tú tù tù

Notable Apache

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Basso, Keith H. (1983). Western Apache. In A. Ortiz (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Southwest (Vol. 10, pp. 462-488). Washingon, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Brugge, David M. (1968). Navajos in the Catholic Church Records of New Mexico 1694 - 1875. Window Rock, Arizona: Research Section, The Navajo Tribe.

- Brugge, David M. (1983). Navajo prehistory and history to 1850. In A. Ortiz (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Southwest (Vol. 10, pp. 489-501). Washingon, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Etulain, Richard W. New Mexican Lives: A Biographical History. University of New Mexico Center for the American West, University of New Mexico Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8263-2433-9

- Foster, Morris W; & McCollough, Martha. (2001). Plains Apache. In R. J. DeMallie (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, pp. 926-939). Washingon, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Goodwin, Greenville [1941] (1969). in Basso, Keith H: The Social Organization of the Western Apache. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arisona Press. LCCN 76-75453.

- Gunnerson, James H. (1979). Southern Athapaskan archeology. In A. Ortiz (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Southwest (Vol. 9, pp. 162-169). Washingon, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Haley, James L. Apaches: A History and Culture Portrait. University of Oklahoma Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8061-2978-6.

- Hammond, George P. and Rey, Agapito (editors). Narratives of the Coronado Expedition 1540-1542. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1940.

- Henderson, Richard. “Replicating Dog Travois Travel on the Northern Plains.” Plains Anthropologist, V39:145-59, 1994.

- Hodge, F. W., editor. Handbook of American Indians, Washington, 1907.

- Hoijer, Harry. (1938). The southern Athapaskan languages. American Anthropologist, 40 (1), 75-87.

- Hoijer, Harry. (1971). The position of the Apachean languages in the Athapaskan stock. In K. H. Basso & M. E. Opler (Eds.), Apachean culture history and ethnology (pp. 3-6). Anthropological papers of the University of Arizona (No. 21). Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Huld, Martin E. (1983). Athapaskan bears. International Journal of American Linguistics, 49 (2), 186-195.

- Krauss, Michael E. (1973). Na-Dene. In T. A. Sebeok (Ed.), Linguistics in North America (pp. 903-978). Current trends in linguistics (Vol. 10). The Hague: Mouton. (Reprinted 1976).

- Opler, Morris E. (1936). The kinship systems of the Southern Athapaskan-speaking tribes. American Anthropologist, 38 (4), 620-633.

- Opler, Morris E. (1975). Problems in Apachean cultural history, with special reference to the Lipan Apache. Anthropological Quarterly, 48 (3), 182-192.

- Opler, Morris E. (1983). The Apachean culture pattern and its origins. In A. Ortiz (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Southwest (Vol. 10, pp. 368-392). Washingon, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Opler, Morris E. (1983). Chiricahua Apache. In A. Ortiz (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Southwest (Vol. 10, pp. 401-418). Washingon, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Opler, Morris E. (1983). Mescalero Apache. In A. Ortiz (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Southwest (Vol. 10, pp. 419-439). Washingon, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Opler, Morris E. (2001). Lipan Apache. In R. J. DeMallie (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, pp. 941-952). Washingon, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Plog, Stephen. Ancient Peoples of the American Southwest. Thames and London, LTD, London, England, 1997. ISBN 0-500-27939-X.

- Sweeney, Edwin R. (1998). Mangas Coloradas: Chief of the Chiricahua Apaches. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3063-6

- Terrell, John Upton (1972). Apache Chronicle . World Publishing. ISBN 0-529-04520-6.

- Tiller, Veronica E. (1983). Jicarilla Apache. In A. Ortiz (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Southwest (Vol. 10, pp. 440-461). Washingon, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

External links

- American Indian Language Development Institute (has children's video of Catcus Boy story in Western Apache)

- Apache Times (San Carlos)

- Tonto Apache Tribe (Arizona Intertribal Council)

- Yavapai-Apache Nation (Arizona Intertribal Council)

- White Mountain Apache Tribe (Arizona Intertribal Council)

- San Carlos Apache Tribe (Arizona Intertribal Council)

- official Yavapai-Apache Nation website

- Post-Contact Social Organization of Three Apache Tribes

- about San Carlos Apache

- White Mountain Apache photographs

- photos, facts, opinions on White Mountain Apaches & the Fort Apache Reservation

- Puberty Ceremony of White Mountain Apaches (information & photo)

- US government's plan to exterminate Apaches

- Apache Language Sample

- Bibliography from Kevin Reeve

- Indians of Arizona (from History of Arizona)

- The Apache (from History of Arizona)

- Apache myths & texts

- Grenville Goodwin's preface to Myths and Tales of the White Mountain Apache

- The Handbook of Texas Online: Apache Indians

- Online Etymology Dictionary

- Inde (Apache) Literature

- Countries and Their Cultures: Apaches

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.