Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (November 25, 1835 – August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-born American businessman, a major philanthropist, and the founder of the Carnegie Steel Company which later became U.S. Steel. At the height of his career, he was the second-richest person in the world, behind only John D. Rockefeller. He is known for having built one of the most powerful and influential corporations in United States history, and, later in his life, giving away most of his riches to fund the establishment of many libraries, schools, and universities in Scotland, America, and worldwide.

Carnegie's writings provide insight into his philosophy of successful wealth accumulation and subsequent use for the betterment of humankind. These constitute the internal aspect of his legacy, supporting his own desire that humankind as a whole move toward a society of peace.

Life

The Carnegie family in Scotland

Andrew Carnegie was born on November 25, 1835, in Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland. He was the son of a hand loom weaver, William Carnegie. His mother was Margaret, daughter of Thomas Morrison, a tanner and shoemaker. Although his family was impoverished, he grew up in a cultured, politically educated home.

Many of Carnegie's closest relatives were self-educated tradesmen and class activists. William Carnegie, although poor, had educated himself and, as far as his resources would permit, ensured that his children received an education. William Carnegie was politically active, and was involved with those organizing demonstrations against the Corn laws. He was also a Chartist. He wrote frequently to newspapers and contributed articles in the radical pamphlet, Cobbett's Register edited by William Cobbett. Amongst other things, he argued for abolition of the Rotten Boroughs and reform of the British House of Commons, Catholic Emancipation, and laws governing safety at work, which were passed many years later in the Factory Acts. Most radically of all, however, he promoted the abolition of all forms of hereditary privilege, including all monarchies.

Another great influence on the young Andrew Carnegie was his uncle, George Lauder, a proprietor of a small grocer's shop in Dunfermline High Street. This uncle introduced the young Carnegie to such historical Scottish heroes as Robert the Bruce, William Wallace, and Rob Roy. He was also introduced to the writings of Robert Burns, as well as William Shakespeare. Lauder had Carnegie commit to memory many pages of Burns' writings, writings that were to stay with him for the rest of his life. Lauder was also interested in the United States. He saw the U.S. as a country with "democratic institutions." Carnegie would later grow to consider the U.S. the role model for democratic government.

Another uncle, his mother's brother, "Ballie" Morrison, was also a radical political firebrand. A fervent nonconformist, the chief objects of his tirades were the Church of England and the Church of Scotland. In 1842 the young Carnegie's radical sentiments were stirred further at the news of "Ballie" being imprisoned for his part in a "Cessation of Labor" (strike). At that time, withdrawal of labor by a hireling was a criminal offense.

Migration to America

Andrew Carnegie's father worked as a jobbing hand loom weaver. This involved receiving the mill's raw materials at his cottage, and weaving them into cloth on the primitive loom in his home. In the 1840s, a new system was coming into being, the factory system. During this era, mill owners began constructing large weaving mills with looms powered at first by waterwheels and later by steam engines. These factories could produce cloth at far lower cost, partly through increased mechanization and economies of scale, but partly also by paying mill workers very low wages and by working them very long hours. The success of the mills forced William Carnegie to seek work in the mills or elsewhere away from home. However, his radical views were well known, and Carnegie was not wanted.

William Carnegie chose to emigrate. His mother's two sisters had already emigrated, but it was his wife who persuaded William Carnegie to make the passage. This was not easy, however, for they had to find the passage money. They were forced to sell their meager possessions and borrow some £20 from friends, a considerable sum in 1848.

That May, his family immigrated to the United States, sailing on the Wiscasset, a former whaler that took the family from Broomielaw, in Glasgow to New York. From there they proceeded up the Hudson River and the Erie Canal to Lake Erie and then to Allegheny, Pennsylvania (present day Pittsburgh's northside neighborhoods), where William Carnegie found work in a cotton factory.

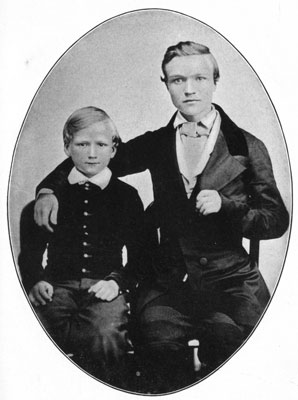

The 12-year-old Andrew Carnegie found work in the same building as a "bobbin boy" for the sum of $1.20 a week. His brother, Thomas, eight years younger, was sent to school. Andrew Carnegie quickly grew accustomed to his new country: three years after arriving in the United States, he began writing to his friends in Scotland extolling the great virtues of American democracy, whilst disparaging and criticizing "feudal British institutions." At the same time, he followed in his father's footsteps and wrote letters to the newspapers, including the New York Tribune, on subjects such as slavery.

Later personal life

Carnegie married Louise Whitfield in 1887 and had one daughter, Margaret, who was born in 1897.

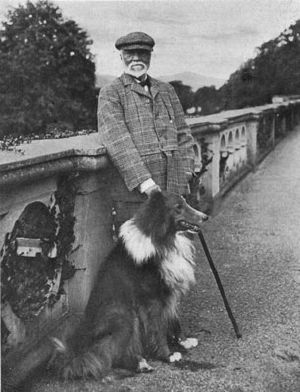

In an era in which financial capital was consolidated in New York City, Carnegie famously stayed aloof from the city, preferring to live near his factories in western Pennsylvania and at Skibo Castle, Scotland, which he bought and refurbished. However, he also built (in 1901) and resided in a townhouse on New York City's Fifth Avenue that later came to house Cooper-Hewitt's National Design Museum.

By the rough and ready standards of nineteenth-century tycoons, Carnegie was not a particularly ruthless man, but the contrast between his life and the lives of many of his own workers and of the poor, in general, was stark. "Maybe with the giving away of his money," commented biographer Joseph Frazier Wall, "he would justify what he had done to get that money."

By the time he died in Lenox, Massachusetts, on August 11, 1919, Carnegie had given away $350,695,653. At his death, the last $30,000,000 was likewise given away to foundations, charities, and to pensioners.

He is interred in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Sleepy Hollow, New York.

Early career

1850–1860: A 'self made man'

Andrew Carnegie's education and passion for reading was given a great boost by Colonel James Anderson, who opened his personal library of four hundred volumes to working boys each Saturday night. Carnegie was a consistent borrower. He was a "self-made man" in the broadest sense, insofar as it applied not only to his economic success but also to his intellectual and cultural development. His capacity and willingness for hard work, his perseverance, and his alertness, soon brought forth opportunities.

1860–1865: Carnegie during the U.S. Civil War

During the pre-war period, Andrew Carnegie had formed a partnership with a Mr. Woodruff, inventor of the sleeping car. The great distances transversed by railways had meant stopping for the night at hotels and inns by the rail side, so that passengers could rest. The sleeping car sped up travel and helped settle the American west. The investment proved a success and a source of great fortune for Woodruff and Carnegie.

The young Carnegie, who had originally been engaged as a telegraph clerk and operator with the Atlantic and Ohio Company, had become the superintendent of the western division of the entire line. In this post, Carnegie was responsible for several improvements in the service. When the American Civil War began in 1861, he accompanied Scott, the Assistant United States Secretary of War, to the front, where he was "the first casualty of the war" pulling up telegraph wires the confederates had buried—the wire came up too quickly and cut his cheek. He would tell the story of that scar for years to come.

Following his good fortune, Carnegie proceeded to increase it still further through fortunate and careful investments. In 1864 Carnegie invested the sum of $40,000 in Storey Farm on Oil Creek, in Venango County, Pennsylvania. In one year, the farm yielded over $1,000,000 in cash dividends, and oil from wells on the property sold profitably.

Aside from Carnegie's investment successes, he was beginning to figure prominently in the American cause and in American culture. With the Civil War raging, Carnegie soon found himself in Washington, D.C. His boss at the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, Thomas A. Scott, who was now Assistant Secretary of War in charge of military transportation, invited Carnegie to join him. Carnegie was appointed superintendent of the military railways and the Union Government's telegraph lines in the East, and was Scott's right hand man. Carnegie, himself, was on the footplate of the locomotive that pulled the first brigade of Union troops to reach Washington. Shortly after this, following the defeat of Union forces at Bull Run, he personally supervised the transportation of the defeated forces. Under his organization, the telegraph service rendered efficient service to the Union cause and significantly assisted in the eventual victory.

The Civil War, as so many wars before it, brought boom times to the suppliers of war. The U.S. iron industry was one such. Before the war its production was of little significance, but the sudden huge demand brought boom times to Pittsburgh and similar cities, and great wealth to the iron masters.

Carnegie had some investments in this industry before the war and, after the war, left the railroads to devote all his energies to the iron works. Carnegie worked to develop several iron works, eventually forming The Keystone Bridge Works and the Union Ironworks in Pittsburgh. Although he had left the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, he did not sever his links with the railroads. These links would prove valuable. The Keystone Bridge Company made iron train bridges, and, as company superintendent, Carnegie had noticed the weakness of the traditional wooden structures. These were replaced in large numbers with iron bridges made in his works. Thus, by the age of 30, Carnegie had an annual income of $50,000.

As well as having good business sense, Carnegie possessed charm and literary knowledge. He was invited to many important social functions, functions that Carnegie exploited to the fullest extent.

Carnegie’s philanthropic inclinations began some time before retirement. He wrote:

I propose to take an income no greater than $50,000 per annum! Beyond this I need ever earn, make no effort to increase my fortune, but spend the surplus each year for benevolent purposes! Let us cast aside business forever, except for others. Let us settle in Oxford and I shall get a thorough education, making the acquaintance of literary men. I figure that this will take three years active work. I shall pay especial attention to speaking in public. We can settle in London and I can purchase a controlling interest in some newspaper or live review and give the general management of it attention, taking part in public matters, especially those connected with education and improvement of the poorer classes. Man must have an idol and the amassing of wealth is one of the worst species of idolatry! No idol is more debasing than the worship of money! Whatever I engage in I must push inordinately; therefore should I be careful to choose that life which will be the most elevating in its character. To continue much longer overwhelmed by business cares and with most of my thoughts wholly upon the way to make more money in the shortest time, must degrade me beyond hope of permanent recovery. I will resign business at thirty-five, but during these ensuing two years I wish to spend the afternoons in receiving instruction and in reading systematically!

Carnegie the industrialist

1885–1900: Building an empire of steel

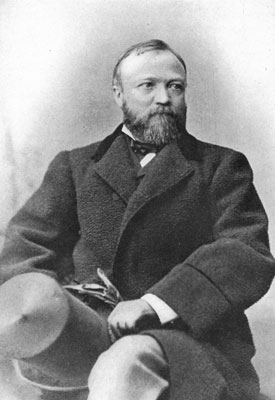

All this was only a preliminary to the success attending his development of the iron and steel industries at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Carnegie made his fortune in the steel industry, controlling the most extensive integrated iron and steel operations ever owned by an individual in the United States. His great innovation was in the cheap and efficient mass production of steel rails for railroad lines.

In the late 1880s, Carnegie was the largest manufacturer of pig-iron, steel-rails, and coke in the world, with a capacity to produce approximately 2,000 tons of pig metal a day. In 1888 he bought the rival Homestead Steel Works, which included an extensive plant served by tributary coal and iron fields, a railway 425 miles long, and a line of lake steamships. An agglutination of the assets of he and his associates occurred in 1892 with the launching of the Carnegie Steel Company.

By 1889, the U.S. output of steel exceeded that of the UK, and Andrew Carnegie owned a large part of it. Carnegie had risen to the heights he had by being a supreme organizer and judge of men. He had the talent of being able to surround himself with able and effective men, while, at the same time, retaining control and direction of the enterprise. Included in these able associates were Henry Clay Frick and Carnegie's younger brother, Thomas. In 1886, tragedy struck Carnegie when Thomas died at the early age of 43. Success in the business continued, however. At the same time as owning steel works, Carnegie had purchased, at low cost, the most valuable of the iron ore fields around Lake Superior.

Carnegie's businesses were uniquely organized in that his belief in democratic principles found itself interpreted into them. This did not mean that Carnegie was not in absolute control, however. The businesses incorporated Carnegie's own version of profit sharing. Carnegie wanted his employees to have a stake in the business, for he knew that they would work best if they saw that their own self-interest was allied to the firm's. As a result, men who had started as laborers in some cases eventually ended up millionaires. Carnegie also often encouraged unfriendly competition between his workers and goaded them into outdoing one another. These rivalries became so important to some of the workers that they refused to talk to each other for years.

Carnegie maintained control by incorporating his enterprises not as joint stock corporations but as limited partnerships with Carnegie as majority and controlling partner. Not a cent of stock was publicly sold. If a member died or retired, his stock was purchased at book value by the company. Similarly, the other partners could vote to call in stock from those partners who underperformed, forcing them to resign.

The internal organization of his businesses was not the only reason for Andrew Carnegie's rise to pre-eminence. Carnegie introduced the concept of counter-cyclical investment. Carnegie's competitors, along with virtually every other business enterprise across the globe, pursued the conventional strategy of procyclical investment: manufacturers reinvesting profits in new capital in times of boom and high demand. Because demand is high, investment in bull markets is more expensive. In response, Carnegie developed and implemented a secret tactic. He shifted the purchasing cycle of his companies to slump times, when business was depressed and prices low. Carnegie observed that business cycles alternated between "boom" and "bust." He saw that if he capitalized during a slump, his costs would be lower and profits higher.

During the years 1893 to 1897, there was a great slump in economic demand, and so Carnegie made his move. At rock bottom prices, he upgraded his entire operation with the latest and most cost effective steel mills. When demand picked up, prosperity followed for Carnegie Steel. In 1900, the profits were $40,000,000, with $25,000,000 being Carnegie's share.

1892: The Homestead Strike

The Homestead Strike was a bloody labor confrontation lasting 143 days in 1892, and was one of the most serious in U.S. history. The conflict was situated around Carnegie Steel's main plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania, and grew out of a dispute between the National Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers of the United States and the Carnegie Steel Company.

Carnegie, who had cultivated a pro-labor image in his dealings with company mill workers, departed the country for a trip to his Scottish homeland before the unrest peaked. In doing so, Carnegie left mediation of the dispute in the hands of his associate and partner Henry Clay Frick. Frick was well known in industrial circles as maintaining staunch anti-union sensibilities.

The company had attempted to cut the wages of the skilled steel workers, and when the workers refused the pay cut, management locked the union out (workers considered the stoppage a "lockout" by management and not a "strike" by workers). Frick brought in thousands of strikebreakers to work the steel mills and Pinkerton National Detective agents to safeguard them.

The arrival, on July 6, of a force of three hundred Pinkerton agents from New York City and Chicago resulted in a fight in which ten men—seven strikers and three Pinkertons—were killed and hundreds were injured. Pennsylvania Governor Robert Pattison discharged two brigades of the state militia to the strike site. Then, allegedly in response to the fight between the striking workers and the Pinkertons, anarchist Alexander Berkman tried to kill Frick with a gun provided by Emma Goldman. However, Frick was only wounded, and the attempt turned public opinion away from the striking workers. Afterwards, the company successfully resumed operations with non-union immigrant employees in place of the Homestead plant workers, and Carnegie returned stateside.

1901: The formation of U.S. Steel

In 1901 Carnegie was 65 years old and considering retirement. He reformed his enterprises into conventional joint stock corporations as preparation to this end. Carnegie, however, wanted a good price for his stock. There was a man who was to give him his price. This man was John Pierpont Morgan.

Morgan was a banker and perhaps America's most important financial dealmaker. He had observed how efficiency produced profit. He envisioned an integrated steel industry that would cut costs, lower prices to consumers and raise wages to workers. To this end he needed to buy out Carnegie and several other major producers, and integrate them all into one company, thereby eliminating duplication and waste. Negotiations were concluded on March 2, with the formation of the United States Steel Corporation. It was the first corporation in the world with a market capitalization in excess of one billion U.S. dollars.

The buyout, which was negotiated in secret by Charles M. Schwab, was the largest such industrial takeover in United States history to date. The holdings were incorporated in the United States Steel Corporation, a trust organized by J.P. Morgan, and Carnegie himself retired from business. His steel enterprises were bought out at a figure equivalent to twelve times their annual earnings; $480 million, which at the time was the largest ever personal commercial transaction. Andrew Carnegie's share of this amounted to a massive $225,639,000, which was paid to Carnegie in the form of fine percent, 50-year gold bonds.

A special vault was built to house the physical bulk of nearly $230 million worth of bonds. It was said that "...Carnegie never wanted to see or touch these bonds that represented the fruition of his business career. It was as if he feared that if he looked upon them they might vanish like the gossamer gold of the leprechaun. Let them lie safe in a vault in New Jersey, safe from the New York tax assessors, until he was ready to dispose of them..."

As they signed the papers of sale, Carnegie remarked, "Well, Pierpont, I am now handing the burden over to you." In return, Andrew Carnegie became one of the world's wealthiest men. Retirement was a stage in life that many men dreaded. However, Carnegie was not one of them. He was looking forward to retirement, for it was his intention to follow a new course from that point on.

Carnegie the philanthropist

Andrew Carnegie spent his last years as a philanthropist. From 1901 forward, public attention was turned from the shrewd business capacity that had enabled Carnegie to accumulate such a fortune, to the public-spirited way in which he devoted himself to utilizing it on philanthropic objects. His views on social subjects and the responsibilities which great wealth involved were already known from Triumphant Democracy (1886), and from his Gospel of Wealth (1889). He acquired Skibo Castle, in Sutherland, Scotland, and made his home partly there and partly in New York. He then devoted his life to the work of providing the capital for purposes of public interest and social and educational advancement.

In all his ideas, he was dominated by an intense belief in the future and influence of the English-speaking people, in their democratic government and alliance for the purpose of peace and the abolition of war, and in the progress of education on nonsectarian lines. He was a powerful supporter of the movement for spelling reform as a means of promoting the spread of the English language.

Among all of his many philanthropic efforts, the establishment of public libraries in the United States, the United Kingdom, and in other English-speaking countries was especially prominent. Carnegie libraries, as they were commonly called, sprang up on all sides. The first of which was opened in 1883 in Dunfermline, Scotland. His method was to build and equip, but only on condition that the local authority provided site and maintenance. To secure local interest, in 1885 he gave $500,000 to Pittsburgh for a public library, and in 1886, he gave $250,000 to Allegheny City for a music hall and library, and $250,000 to Edinburgh, Scotland, for a free library. In total, Carnegie funded some three thousand libraries, located in every U.S. state except Alaska, Delaware, and Rhode Island, in Canada, Britain, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, the West Indies, and Fiji.

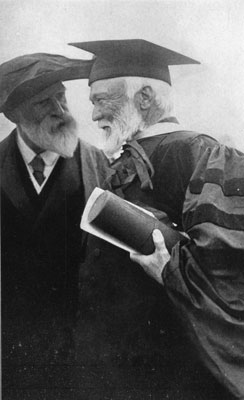

He gave $2 million in 1901 to start the Carnegie Institute of Technology (CIT) in Pittsburgh and the same amount in 1902 to found the Carnegie Institution in Washington, D.C. CIT is now part of Carnegie Mellon University. He later contributed more to these and other schools.

In Scotland, he gave $2 million in 1901 to establish a trust for providing funds for assisting education at Scottish universities, a benefaction which resulted in his being elected Lord Rector of the University of St. Andrews. He was a large benefactor of the Tuskegee Institute under Booker T. Washington for African American education. He also established large pension funds in 1901 for his former employees at Homestead and, in 1905, for American college professors. He also funded the construction of seven thousand church organs.

Also, long before he sold out, in 1879, he erected commodious swimming-baths for the use of the people of his hometown of Dunfermline, Scotland. In the following year, Carnegie gave $40,000 for the establishment of a free library in the same city. In 1884, he gave $50,000 to Bellevue Hospital Medical College to found a histological laboratory, now called the Carnegie Laboratory.

He owned Carnegie Hall in New York City from its construction in 1890 until his widow sold it in 1924.

He also founded the Carnegie Hero Fund commissions in America (1904) and in the United Kingdom (1908) for the recognition of deeds of heroism, contributed $500,000 in 1903 for the erection of a Peace Palace at The Hague, and donated $150,000 for a Pan-American Palace in Washington as a home for the International Bureau of American Republics. In 1910 he founded the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, which continues to provide significant support for peace scholars.

Carnegie the scholar and activist

Whilst Carnegie continued his business career, some of his literary intentions were fulfilled. During this time, he made many friends and acquaintances in the literary and political worlds. Among these were such as Matthew Arnold and Herbert Spencer, as well as most of the U.S. presidents, statesmen, and notable writers of the time. Many were visitors to the Carnegie home. Carnegie greatly admired Herbert Spencer, the polymath who seemed to know everything. He did not, however, agree with Spencer's Social Darwinism, which held that philanthropy was a bad idea.

In 1881 Andrew Carnegie took his family, which included his mother, then aged 70, on a trip to Great Britain. Carnegie's charm aided by his great wealth meant that he had many British friends, including Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone. They toured the sights of Scotland by coach having several receptions en-route. The highlight for them all was a triumphal return to Dunfermline where Carnegie's mother laid the foundation stone of the "Carnegie Library." Andrew Carnegie's criticism of British society did not run to a dislike of the country of his birth; on the contrary, one of Carnegie's ambitions was to act as a catalyst for a close association between the English speaking peoples. To this end, he purchased, in the first part of the 1880s, a number of newspapers in England, all of which were to advocate the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of "the British Republic".

Following his tour of Great Britain, Carnegie wrote about his experiences in a book entitled An American Four-in-hand in Britain. Although still actively involved in running his many businesses, Carnegie had become a regular contributor of articles to numerous serious-minded magazines, most notably the Nineteenth Century, under the editorship of James Knowles, and the North American Review, whose editor, Lloyd Bryce, oversaw the publication during its most influential period.

In 1886 Carnegie penned his most radical work to date, entitled Triumphant Democracy. The work, liberal in its use of statistics to make its arguments, was an attempt to argue his view that the American republican system of government was superior to the British monarchical system. It not only gave an overly-favorable and idealistic view of American progress, but made some considerable criticism of the British royal family. Most antagonistic, however, was the cover that depicted amongst other motifs, an upended royal crown and a broken scepter. Given these aspects, it was no surprise that the book was the cause of some considerable controversy in Great Britain. The book itself was successful. It made many Americans aware for the first time of their country's economic progress and sold over 40,000 copies, mostly in the U.S.

In 1889 Carnegie stirred up yet another hornet's nest when an article entitled "Wealth" appeared in the June issue of the North American Review. After reading it, Gladstone requested its publication in England, and it appeared under a new title, "The Gospel of Wealth" in the Pall Mall Gazette. The article itself was the subject of much discussion. In the article, the author argued that the life of a wealthy industrialist such as Carnegie should comprise two parts. The first part was the gathering and the accumulation of wealth. The second part was to be used for the subsequent distribution of this wealth to benevolent causes. Carnegie condemned those who sought to retain their wealth for themselves, claiming that a "man who dies rich dies disgraced."

Philosophy

In The Gospel of Wealth, Carnegie stated his belief that the rich should use their wealth to help enrich society.

The following is taken from one of Carnegie's memos to himself:

Man does not live by bread alone. I have known millionaires starving for lack of the nutriment which alone can sustain all that is human in man, and I know workmen, and many so-called poor men, who revel in luxuries beyond the power of those millionaires to reach. It is the mind that makes the body rich. There is no class so pitiably wretched as that which possesses money and nothing else. Money can only be the useful drudge of things immeasurably higher than itself. Exalted beyond this, as it sometimes is, it remains Caliban still and still plays the beast. My aspirations take a higher flight. Mine be it to have contributed to the enlightenment and the joys of the mind, to the things of the spirit, to all that tends to bring into the lives of the toilers of Pittsburgh sweetness and light. I hold this the noblest possible use of wealth.

Carnegie also believed that achievement of financial success could be reduced to a simple formula, which could be duplicated by the average person. In 1908 he commissioned (at no pay) Napoleon Hill, then a journalist, to interview more than five hundred wealthy achievers to determine the common threads of their success. Hill eventually became a Carnegie collaborator, and their work was published in 1928, after Carnegie's death, in Hill's book The Law of Success, and in 1937 in Hill's most successful and enduring work, Think and Grow Rich.

Legacy

Andrew Carnegie's direct descendants still live in Scotland today. William Thomson CBE, the great grandson of Andrew, is Chairman of the Carnegie Trust Dunfermline, a trust that maintains Andrew Carnegie's legacy.

Carnegie left literary works that can help many people understand the ways of success and how to maintain that success. His writings teach not only about wealth but also about its purpose and how it should be used for the betterment of society as a whole:

This, then, is held to be the duty of the man of wealth: first, to set an example of modest unostentatious living, shunning display; to provide moderately for the legitimate wants of those dependent upon him; and, after doing so, to consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds which he is strictly bound as a matter of duty to administer in the manner which, in his judgment, is best calculated to produce the most beneficial results for the community.'

Think and Grow Rich, written by Carnegie's collaborator, Napoleon Hill—which further details Carnegie's philosophy—has not been out of print since the day it was published, with more than 30 million copies sold worldwide. In 1960 Hill published an abridged version of the book containing the Andrew Carnegie formula for wealth creation, which for years was the only version generally available. In 2004 Ross Cornwell published Think and Grow Rich!: The Original Version, Restored and Revised, which restored the book to its original form, with slight revisions, and added comprehensive endnotes, index, and appendix.

Andrew Carnegie’s legacy lives on in the hundreds of libraries, institutions, and philanthropic efforts that his wealth made possible. His spirit as well as his faith in the ability of individuals to better themselves and thus the society in which they live, is a beacon of light for future generations to follow.

Publications

- Carnegie, Andrew. Triumphant Democracy (1886)

- Carnegie, Andrew.Gospel of Wealth (1900)

- Carnegie, Andrew. An American Four-in-hand in Britain (1883)

- Carnegie, Andrew. Round the World (1884)

- Carnegie, Andrew. The Empire of Business (1902)

- Carnegie, Andrew. Life of James Watt (1905)

- Carnegie, Andrew. Problems of To-day (1908)

- Carnegie, Andrew. Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie (1920, 2006). ISBN 1599869675.

- Carnegie, Andrew "Wealth" June, North American Review. Published as The Gospel of Wealth. 1998. Applewood Books. ISBN 1557094713

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hill, Napoleon. 1928. The Law of Success ISBN 0879804475

- Hill, Napoleon. Think and Grow Rich (1937, 2004). ISBN 1593302002. (Contains Hill's reminiscences about his long relationship with Carnegie and extensive endnotes about him.)

- Josephson; Matthew. The Robber Barons: The Great American Capitalists, 1861-1901 (1938, 1987). ISBN 9991847995.

- Morris, Charles R. The Tycoons: How Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould, and J. P. Morgan Invented the American Supereconomy (2005). ISBN 0805075992.

- Krass, Peter. Carnegie (2002). ISBN 0471386308.

- Livesay, Harold C. Andrew Carnegie and the Rise of Big Business, 2nd Edition (1999). ISBN 0321432878.

- Ritt Jr., Michael J., and Landers, Kirk. A Lifetime of Riches. ISBN 0525941460.

- Wall, Joseph Frazier. Andrew Carnegie (1989). ISBN 0822959046.

- Wall, Joseph Frazier, ed. The Andrew Carnegie Reader (1992). ISBN 0822954648

- Whaples, Robert. "Andrew Carnegie", EH.Net Encyclopedia of Economic and Business History.

- The Carnegie Legacy

- The Richest Man in the World: Andrew Carnegie film by Austin Hoyt.

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Appleton's Cyclopedia of American Biography.

External links

All links retrieved June 19, 2021.

- Carnegie Corporation of New York

- Carnegie Council

- Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh: Andrew Carnegie: A Tribute

- Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching

- Carnegie Birthplace Museum website

- Online Books by Andrew Carnegie

- Works by Andrew Carnegie. Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.