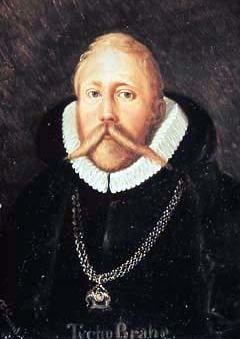

Tycho Brahe

- This article is about the astronomer.

| Tycho Ottesen Brahe | |

| |

| Born | December 14, 1546 Knutstorp Castle, Denmark |

|---|---|

| Died | October 24, 1601 (aged 54) Prague |

| Nationality | Danish |

| Education | private |

| Occupation | nobleman, astronomer |

| Spouse(s) | Kirsten Jørgensdatter |

| Children | 8 |

| Parents | Otte Brahe and Beate Bille |

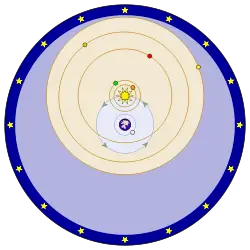

Tycho Brahe, born Tyge Ottesen Brahe (December 14, 1546 â October 24, 1601), was a Danish astronomer whose measurements of stellar and planetary positions achieved unparalleled accuracy for their time. He was the last major astronomer to work without the aid of a telescope. His observations formed the basis for Johannes Kepler's laws of planetary motion. He also developed an innovative geocentric model of the Solar System in which the Sun and Moon circled the Earth, while the planets other than Earth circled the Sun.

Life

Early years

Tycho Brahe was born Tyge Ottesen Brahe (de Knutstorp), adopting the Latinized form Tycho around age 15 (sometimes written Tÿcho). He was born at his family's ancestral seat of Knutstorp Castle, Denmark to Otte Brahe and Beate Bille. His twin brother died before being baptized. (Tycho wrote a Latin ode [1] to his dead twin, which was printed as his first publication in 1572). He also had two sisters, one older (Kirstine Brahe) and one younger (Sophia Brahe). Otte Brahe, Tycho's father, was a nobleman and an important figure in the Danish King's court. His mother, Beate Bille, also came from an important family that had produced leading churchmen and politicians. In his youth he lived at Hvedborg Manor, Funen, Denmark with his uncle and attended Horne Church in nearby Horne.

Tycho later wrote that when he was around two, his uncle, Danish nobleman Jørgen Brahe, absconded with him without his parents' knowledge. Tycho's father had promised to allow his uncle to adopt one of his children, but when Tycho was born, his parents lost heart and kept the child. A year or so later, upon the birth of a second son, Uncle Jørgen took the older boy.[2] Apparently, this did not lead to any disputes nor did his parents attempt to retrieve the child. Tycho lived with his uncle and aunt at Tostrup Castle until he was six years old. Around 1552, his uncle was given command of Vordingborg Castle to which they moved, and where Tycho began a Latin education until he was 12 years old.

On April 19, 1559, Tycho began his studies at the University of Copenhagen. There, following the wishes of his uncle, he studied law among other subjects, including astronomy. It was, however, the eclipse that occurred on August 21, 1560, particularly the fact that it had been predicted, that so impressed him that he began to make his own studies of astronomy, helped by some professors. He purchased an ephemeris and books such as Sacrobosco's Tractatus de Sphaera, Apianus's Cosmographia seu descriptio totius orbis, and Regiomontanus's De triangulis omnimodis. During this time, he especially relied on a classic work by Ptolemy on astronomy, and his personal copy survives along with the notes that he scribbled in its margins.[2]

In 1562, Tycho's uncle sent him with a tutor to the University of Leipzig to finish his education, the hope being that he would focus on studies that would prepare him for a career in law or statesmanship. Tycho, however, made it clear by his actions, both overt and covert, that astronomy, and its related discipline, astrology, were the only pursuits worthy of his time. Realizing the deficiencies in the state of astronomy, particularly in tables of the Moon, stars and planets, he made instruments by hand that would enable him to more accurately chart the heavens.

Tycho was able to improve and enlarge existing instruments, and construct entirely new ones. Tycho's naked eye measurements of planetary parallax were accurate to the arcminute. His sister, Sophia, assisted Tycho in many of his measurements. These jealously guarded measurements were "usurped" by Kepler following Tycho's death.[3] Tycho was the last major astronomer to work without the aid of a telescope, soon to be turned toward the sky by Galileo.

Tycho's nose

In 1565, Tycho's uncle died of pneumonia after rescuing Frederick II of Denmark from drowning, and Tycho returned home to claim his inheritance. He was not, however, greeted with open arms by his relatives and colleagues in Denmark, who were critical of his chosen vocation. This misunderstanding led Tycho to seek a more congenial environment outside of his native land, and he embarked on a tour of the continent.[4]

It was at the beginning of this journey that Tycho lost part of his nose in a duel with rapiers with Manderup Parsbjerg, a fellow Danish nobleman. This occurred in the Christmas season of 1566, after a fair amount of drinking, while the just-turned 20-year-old Tycho had stopped at the University of Rostock in Germany. Attending a dinner at a professor's house, he quarreled with Parsbjerg, it is said, over a matter of geometry. A subsequent duel (in the dark) resulted in Tycho losing the bridge of his nose. A consequence of this was that Tycho developed an interest in medicine and alchemy. For the rest of his life, he was said to have worn a replacement made of silver and gold blended into a flesh tone, and used an adhesive balm to keep it attached. However, in 1901 and again in 2010, Tycho's tomb was opened and his remains were examined by medical experts. The nasal opening of the skull was rimmed with green, a sign of exposure to copper, not silver or gold.[5] Some historians have speculated that he wore a number of different prosthetics for different occasions, noting that a copper nose would have been more comfortable and less heavy than a precious metal one.

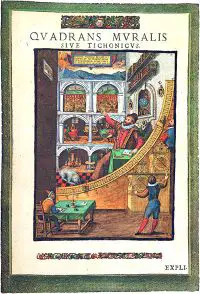

Tycho went on to Augsburg, where he assisted the city's burgomaster, Peter Hainzell, in the construction of an observatory that included a 19-foot quadrant, an instrument used to measure the position of the stars. He continued to travel, visiting a number of observatories in Germany, Switzerland and Italy.[4] At the end of 1570 he was informed about his father's ill health, so he returned to Knudstrup, where his father died on May 9 1571. Soon after, his maternal uncle Steen Bille helped him build an observatory and alchemical laboratory at Herrevad Abbey.

Family life

In 1572, in Knudstrup, Tycho fell in love with Kirsten Jørgensdatter, a commoner whose father, Pastor Jorgen Hansen, was the Lutheran clergyman of Knudstrup's village church. Under Danish law, when a nobleman and a common woman lived together openly as husband and wife, and she wore the keys to the household at her belt like any true wife, their alliance became a binding morganatic marriage after three years.[6] The husband retained his noble status and privileges; the wife remained a commoner. Their children were legitimate in the eyes of the law, but they were commoners like their mother and could not inherit their father's name, coat of arms, or land property [7].

Kirsten Jørgensdatter gave birth to their first daughter, Kirstine (named after Tycho's late sister who died at 13) on October 12, 1573. Together they had eight children, six of whom lived to adulthood. In 1574, they moved to Copenhagen where their daughter Magdalene was born. Kirsten and Tycho lived together for almost 30 years until Tycho's death.

Uraniborg

King Frederick II had heard about the fame Tycho was gradually acquiring through his astronomical and astrological pursuits, and invited him to lecture in Copenhagen. Yet even though the monarch had raised his status, Tycho was still dissatisfied with the reception his activities attracted, and he hoped to find a more amenable environment in Switzerland. In 1576, he was in the process of arranging for his family to move to Basel, when he received a message from Frederick granting him a generous annual stipend and promises of assistance in the construction of a new observatory in Hven, an offer Tycho could not refuse.

Construction of the observatory, which he named Uraniborg, commenced in the summer, and the elaborately decorated facilities were soon in operation. From this new headquarters, which included apartments for the entertainment of dignitaries as well as a separate observatory for his students, Tycho received royalty from his home country and from around the world, including an eight-day visit from King James VI of Scotland.[4] During this period at Uraniborg, which was to last 21 years, Tycho made important observations of the planet Mars and of the moon, He was able to discover irregularities in the Moon's motion that became the focus of later researchers who attempted to apply the gravitational theory of Isaac Newton to account for them.

During his years at Uraniborg, Tycho developed a theory of the solar system in which the sun circled the earth, with the rest of the planets circling the sun. This theory was attractive to those who did not want to embrace the heliocentric theory of Nicholas Copernicus in its entirety, and at least two other scientists claimed it as their own. Brahe never fully embraced the Copernican view of the heliocentric solar system.

Years in Prague

After the death of King Frederick II and the succession of his son, Christian IV, Tycho gradually fell out of the graces of the Danish monarchy, at least partly due to the jealousy generated by the international attention the astronomer and his observatory garnered. Tycho is said to have had an impetuous and argumentative disposition, along with a penchant for irony and cynicism in his humor, and these in combination had the gradual effect of undermining his base of support. As a result, his stipend was taken from him, and the lands associated with Uraniborg were also withdrawn, forcing him to find another location to conduct his astronomical research.

Tycho moved to Copenhagen with his family around 1597, and by 1598 had situated himself in the vicinity of Rostock, where he was greeted by the astronomer Henry Rantzau. In 1599, he was received by Emperor Rudolph II, to which he had dedicated his latest work on the position of the planets. Rudolph erected an observatory for Tycho in the vicinity of Prague, and granted the astronomer a generous pension. In spite of the graciousness of his new patron, however, Tycho often longed for the friendships of his abandoned homeland, and grew increasingly suspicious and argumentative. His health declined rapidly toward the end of his life. Still, in 1600, he made what proved to be the monumental decision of inviting Johannes Kepler to join him.

Tycho and Kepler

Kepler had already come to the attention of Tycho through some of his early published works, which Tycho had provided a detailed criticism of. In fact, Tycho intimated that Kepler's theories had led him to increased the accuracy of his measurements. An exchange of letters resulted in Tycho's very forthcoming invitation to join him as a research associate.

For several months Kepler joined Tycho, who promised to intervene with Emperor Rudolph on his behalf to establish a paid position for him at the observatory. But Kepler departed Prague, leaving his wife and children in Tycho's household. In the meantime, he ran out of money, and asked Tycho to assist him, the later obliging without remonstrance. Kepler then left Prague for a second time, and sent an angry letter of accusation against his patron, apparently believing that he had not adequately helped his family and had not shared data on Mars. This data was the very reason Kepler had sought out Tycho, as it bore directly on Kepler's theory of planetary motion.

Tycho had one of his assistants respond with a conciliatory letter, to which Kepler finally responded in tones of regret and repentance. The two were finally reconciled in 1601. Tycho then presented Kepler to the emperor, who bestowed on the young astronomer the title of Imperial Mathematician, accompanied by an obligation to further assist Tycho in his observations and research.

Kepler focused on Tycho's observations on Mars, the compilation of which, it was agreed, would be named the Rudolphine Tables after the emperor. Work on Tycho's stellar observations was left to Longomontanus, another of Tycho's assistants. Longomontanus, however, abandoned Tycho for a teaching position in Denmark, and it was soon after this that Tycho himself began to show the signs of wear to which he was subjected by the stringent schedule he kept.

Death

It was during a visit to a nobleman that Tycho suffered an attack described as a retention of urine. In the week that followed, he suffered unimaginably from the condition that had affected his body. While the immediate symptoms of this condition finally abated, Tycho was left in a considerably weakened state. On the day of his death, he gave final instructions to his family and staff. He died on October 24, 1601, eleven days after first being stricken.[8] Toward the end of his illness he is said to have told Kepler "Ne frustra vixisse videar!" ("Let me not seem to have lived in vain.â)[9] For hundreds of years, the general belief was that he had strained his bladder. It had been said that to leave the banquet before it concluded would be the height of bad manners, and so he remained, and that his bladder, stretched to its limit, developed an infection that he later died of. This theory was supported by Kepler's first-hand account.

Scientists who opened Brahe's grave in 1901 to mark the 300th anniversary of his death claimed they had found mercury in his remains, suggesting that he died not from urinary problems but was poisoned, either intentionally or unintentionally. According to a 2005 book by Joshua and Anne-Lee Gilder, there is substantial circumstantial evidence that Kepler murdered Brahe; they argue that Kepler had the means, motive, and opportunity, and stole Tycho's data on his death.[10] The Gilders find it "unlikely" that Tycho could have poisoned himself, since he was an alchemist known to be familiar with the toxicity of different mercury compounds.

In 2012, two years after Tycho Brahe was exhumed from his grave a second time, researchers conducting chemical analyses of his corpse concluded that mercury poisoning was not the cause of his death. It seems more likely that he did in fact die from an infected bladder.[5]

Kepler inherited Tycho's position after Tycho's death, and completed the Rudolphine Tables in 1627. He attempted to publish Tycho's work almost immediately after the astronomer's death, but the family confiscated Tycho's papers and published the results themselves. Kepler objected, as he insisted that some of the notes in the margins that had been his were published along with Tycho's work.

Tycho Brahe's body is currently interred in a tomb in the Church of Our Lady in front of Týn near the Old Town Square and the Astronomical Clock in Prague.

Career: Observing the heavens

Tycho was the preeminent observational astronomer of the pre-telescopic period and made highly accurate measurements of the positions of stars and planets. For example, he measured Earth's axial tilt as 23 degrees and 31.5 minutes, which he claimed to be more accurate than the Copernican measurement by 3.5 minutes. After his death, his records of the motion of the planet Mars enabled Kepler to discover the laws of planetary motion. These laws provided powerful support for the Copernican heliocentric theory of the Solar System.

Tycho was aware that a star observed near the horizon appears with a greater altitude than the real one, due to atmospheric refraction, and he worked out tables for the correction of this source of error.

Supernova

On November 11, 1572, Tycho observed (from Herrevad Abbey) a very bright star that appeared unexpectedly in the constellation Cassiopeia. Until then, most observers held the Aristotelian concept of "celestial immutability," which was that the stars in heaven were eternal and unchangeable. Thus the sudden appearance of a new star was explained as a phenomenon within the Earth's atmosphere.

Tycho, however, observed that the relative position of the object did not change from night to night, suggesting that the object was far away, at a distance far greater than the diameter of the Earth. He argued that a nearby object should appear to shift its position with respect to the background. He made additional observations about the star, including its brightness, color, and the change in its appearance over time. He published his observations in a small book, De Stella Nova (1573), thereby coining the term nova for a "new" star. We now know that Tycho's star in Cassiopeia was a supernova 7,500 light years from Earth, and it has been named SN 1572.

This discovery was decisive for his choice of astronomy as a profession. Tycho was strongly critical of those who dismissed the implications of the astronomical appearance, writing in the preface to De Stella Nova: "O crassa ingenia. O caecos coeli spectatores." ("Oh thick wits. Oh blind watchers of the sky.")

Tychonic system

To explain the motions of bodies in the Solar System, Tycho constructed a modified geocentric model known as the Tychonic system. In this model, the Earth was taken to be stationary, the Sun and Moon orbited the Earth, and the other planets orbited the Sun.

Kepler tried but failed to persuade Tycho to adopt the Copernican heliocentric model. Tycho's argument in favor of his own model was that if the Earth were in motion, then nearby stars should appear to shift their positions with respect to background stars. In fact, this effect of parallax does exist; but it could not be observed with the naked eye, nor with the telescopes of the next 200 years, because even the nearest stars are much more distant than most astronomers of the time believed possible.

In the years following Galileo's observation of the phases of Venus in 1610, which made the Ptolemaic system intractable, the Tychonic system became the major competitor with Copernicanism. The Tychonic system provided a safe haven for astronomers who were dissatisfied with older models but were reluctant to accept the Earth's motion. It gained a considerable following after 1616, when the Roman Catholic Church adopted it as its official astronomical concept of the universe. The Church argued that the heliocentric model was contrary to both philosophy and Scripture, and could be discussed only as a computational convenience that had no connection to fact.

The Tychonic system also offered another major innovation: the earlier geocentric model and the Copernican heliocentric model relied on the idea of transparent rotating crystalline spheres carrying the planets in their orbits, but Tycho eliminated the spheres entirely.

Astrology

Like the fifteenth-century astronomer Regiomontanus, Tycho Brahe appears to have accepted astrological prognostications on the principle that the heavenly bodies undoubtedly influenced (but did not determine) terrestrial events. Yet he expressed skepticism about the multiplicity of interpretative schemes, and increasingly preferred to work on establishing a sound mathematical astronomy. Two early tracts, one entitled Against Astrologers for Astrology, and one on a new method of dividing the sky into astrological houses, were never published and are now lost.

Tycho also worked in the area of weather prediction, produced astrological interpretations of the supernova of 1572 and the comet of 1577, and furnished his patrons Frederick II and Rudolph II with nativities and other predictions (thereby strengthening the ties between patron and client by demonstrating value). An astrological world view was fundamental to Tycho's entire philosophy of nature. His interest in alchemy, particularly the medical alchemy associated with Paracelsus, was almost as long-standing as his study of astrology and astronomy simultaneously, and Uraniborg was constructed as both observatory and laboratory.

In an introductory oration to the course of lectures he gave in Copenhagen in 1574, Tycho defended astrology on the grounds of correspondences between the heavenly bodies, terrestrial substances (metals, stones, and so forth), and bodily organs (medical astrology). He later emphasized the importance of studying alchemy and astrology together, using a pair of emblems bearing the mottos: Despiciendo suspicio ("By looking down I see upward") and Suspiciendo despicio ("By looking up I see downward"). As several scholars have now argued, Tycho's commitment to a relationship between macrocosm and microcosm even played a role in his rejection of Copernicanism and his construction of a third world-system.

Legacy

Tycho Brahe received international fame in his own lifetime, and his legacy remains as "the first competent mind in modern astronomy to feel ardently the passion for exact empirical facts."[11] Although Tycho's planetary model was soon discredited, his astronomical observations were an essential contribution to the scientific revolution.

The traditional view of Tycho is that he was primarily an empiricist who set new standards for precise and objective measurements. This appraisal originated in Pierre Gassendi's 1654 biography, Tychonis Brahe, equitis Dani, astronomorum coryphaei, vita. It was furthered by Johann Dreyer's biography in 1890, which was long the most influential work on Tycho. According to historian of science Helge Kragh, this assessment grew out of Gassendi's opposition to Aristotelianism and Cartesianism, and fails to account for the diversity of Tycho's activities.[12]

Named after Tycho

- Tycho crater on the Moon

- Tycho Brahe crater on Mars

- Tycho Brahe Planetarium in Copenhagen, Denmark.

- M/F Tycho Brahe, a Scandlines ferry connecting Helsingør in Denmark and Helsingborg in Sweden

See also

Notes

- â Alex Wittendorf, Tyge Brahe (Copenhagen, DK: G.E.C. Gad., 1994), 68.

- â 2.0 2.1 Robert S. Ball, Great astronomers (Fairfield, IA: 1st World Library Literary Society, 2004).

- â Stephen Hawking, The Illustrated on the Shoulders of Giants: The Great Works of Physics and Astronomy (Philadelphia, PA: Running Press, 2004, ISBN 0762418982).

- â 4.0 4.1 4.2 David Brewster, "Brahe, Tycho." In The Edinburgh Encyclopaedia (Edinburgh: W. Blackwood, et. al. 1830), 400-401.

- â 5.0 5.1 Megan Gannon, Tycho Brahe Died from Pee, Not Poison Live Science, November 16, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- â A morganatic marriage is a type of marriage that can be contracted in certain countries, usually between people of unequal social rank, which prevents the passage of the husband's titles and privileges to the wife and any children born of the marriage.

- â Peter Skautrup, Den jyske lov: Text med oversattelse og ordbog (Aarhus, DK: Universitets-forlag, 1941), 24-25.

- â David Brewster, The martyrs of science; or, The lives of Galileo, Tycho Brahe, and Kepler (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1841), 181.

- â David L. Goodstein and Judith R. Goodstein, Feynman's Lost Lecture: The Motion of Planets Around the Sun (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1999, ISBN 0393039188).

- â Joshua Gilder and Anne-Lee Gilder, Heavenly Intrigue: Johannes Kepler, Tycho Brahe, and the Murder Behind One of History's Greatest Scientific Discoveries (New York: Anchor Books, 2005).

- â Edwin Arthur Burtt, The Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Physical Science: A Historical and Critical Essay (Dover Publications, 2003, ISBN 978-0486425511).

- â Helge Kragh, "Received wisdom in biography: Tycho biographies from Gassendi to Christianson." In Thomas Söderqvist (ed.), The History and Poetics of Scientific Biography (Routledge, 2017, ISBN 978-1138264793).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ball, Robert S. Great astronomers. Fairfield, IA: 1st World Library Literary Society, 2004. ISBN 1421814935.

- Brahe, Tycho, John Dreyer (ed.) Tychonis Brahe Dani Opera Omnia. (in Latin). Vol 1-15. Hauniæ, in Libraria Gyldendaliana, 1913-1929.

- Brewster, David. "Brahe, Tycho." In The Edinburgh Encyclopaedia. Edinburgh: W. Blackwood [and others], 1830.

- Brewster, David. The martyrs of science; or, The lives of Galileo, Tycho Brahe, and Kepler. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1841.

- Burtt, Edwin Arthur. The Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Physical Science: A Historical and Critical Essay. Dover Publications, 2003. ISBN 978-0486425511

- Christianson, John Robert. On Tycho's Island: Tycho Brahe, science, and culture in the sixteenth century. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 052165081X.

- Ferguson, Kitty. The Nobleman and His Housedog: Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler: The Strange Partnership that Revolutionised Science. London, UK: Review, 2002. ISBN 0747270228.

- Gilder, Joshua, and Anne-Lee Gilder. Heavenly Intrigue: Johannes Kepler, Tycho Brahe, and the Murder Behind One of History's Greatest Scientific Discoveries. New York: Anchor Books, 2005. ISBN 9781400031764.

- Goodstein, David L. and Judith R. Goodstein. Feynman's Lost Lecture: The Motion of Planets Around the Sun. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1999. ISBN 0393039188

- Hawking, Stephen. The Illustrated on the Shoulders of Giants: The Great Works of Physics and Astronomy. Philadelphia, PA: Running Press, 2004. ISBN 0762418982

- Koestler, Arthur. The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe. New York: Penguin, 1990. ISBN 0140192468

- Olson, Donald W., Marilynn S. Olson, Russell L. Doescher. "The Stars of Hamlet." Sky & Telescope, 1998.

- Skautrup, Peter. Den jyske lov: Text med oversattelse og ordbog. Aarhus, DK: Universitets-forlag, 1941.

- Thoren, Victor E. The Lord of Uraniborg: a biography of Tycho Brahe. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 0521351588.

- Wittendorff, Alex. Tyge Brahe. Copenhagen, DK: G.E.C. Gad., 1994. ISBN 8712022721.

External links

All links retrieved May 2, 2023.

- Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1602 edition - Full digital facsimile, Lehigh University.

- Astronomiae instauratae mechanica, 1602 edition - Full digital facsimile, Smithsonian Institution.

- Tycho Brahe. Skyscript.

- Tycho Brahe The Galileo Project.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.