Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas (Portuguese: Tratado de Tordesilhas, Spanish: Tratado de Tordesillas), signed at Tordesillas (now in Valladolid province, Spain), June 7, 1494, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe into an exclusive duopoly between the Spanish and the Portuguese along a north-south meridian 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands (off the west coast of Africa). This was about halfway between the Cape Verde Islands (already Portuguese) and the islands discovered by Christopher Columbus on his first voyage (claimed for Spain), named in the treaty as Cipangu and Antilia (no doubt Cuba and Hispaniola).

The lands to the east would belong to Portugal and the lands to the west to Spain. The treaty was ratified by Spain (at the time, the Crowns of Castile and Aragon), July 2, 1494, and by Portugal, September 5, 1494. The other side of the world would be divided a few decades later by the Treaty of Saragossa, or Treaty of Zaragoza, signed on April 22, 1529, which specified the anti-meridian to the line of demarcation specified in the Treaty of Tordesillas. Originals of both treaties are kept at the Archivo General de Indias in Spain and at the Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo in Portugal.[1]

Signing and enforcement

The Treaty of Tordesillas was intended to resolve the dispute between the rival kingdoms of Spain and Portugal to newly discovered, and yet-to-be discovered, lands in the Atlantic. A series of papal bulls, after 1452, had attempted to define these claims. In 1481, the papal Bull, Aeterni regis, had granted all land south of the Canary Islands to Portugal. These papal bulls were confirmed, with papal approval, by the Treaty of Alcáçovas-Toledo (1479â1480).

In 1492, Columbus' arrival at supposedly Asiatic lands in the western seas threatened the unstable relations between Portugal and Spain, who had been jockeying for possession of colonial territories along the African coast for many years. The King of Portugal asserted that the discovery was within the bounds set forth in the papal bulls of 1455, 1456, and 1479. The King and Queen of Spain disputed this and sought a new papal bull on the subject. Spanish-born Pope Alexander VI, a native of Valencia and a friend of the Spanish King, responded with three bulls, dated May 3 and 4, 1493, which were highly favorable to Spain. The third of these bulls, Inter caetera, decreed that all lands âwest and southâ of a pole-to-pole line 100 leagues west and south of any of the islands of the Azores or the Cape Verde Islands should belong to Spain, although territory under Christian rule as of Christmas 1492 would remain untouched.

The bull did not mention Portugal or its lands, so Portugal could not claim newly discovered lands even if they were east of the line. Another bull, Dudum siquidem, entitled Extension of the Apostolic Grant and Donation of the Indies and dated September 25, 1493, gave all mainlands and islands then belonging to India to Spain, even if east of the line. The Portuguese King John II was not pleased with this arrangement, feeling that it gave him far too little land and prevented him from achieving his goal of possessing India. (By 1493, Portuguese explorers had only reached the east coast of Africa). He opened negotiations with King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain to move the line to the west and allow him to claim newly discovered lands east of the line. The treaty effectively countered the bulls of Alexander VI and was sanctioned by Pope Julius II in a new bull of 1506.

Very little of the newly divided area had actually been seen. Spain gained lands including most of the Americas. The easternmost part of current Brazil, when it was discovered in 1500 by Pedro Ãlvares Cabral, was granted to Portugal. The line was not strictly enforcedâthe Spanish did not resist the Portuguese expansion of Brazil across the meridian. The treaty was rendered meaningless between 1580 and 1640, while the Spanish King was also King of Portugal. It was superseded by the 1750 Treaty of Madrid, which granted Portugal control of the lands it occupied in South America. However, that treaty was immediately repudiated by Spain.

Lines of demarcation

The Treaty of Tordesillas only specified its demarcation line in leagues from the Cape Verde Islands. It did not specify the line in degrees, nor did it identify the specific island or the specific length of its league. Instead, the treaty stated that these matters were to be settled by a joint voyage, which never occurred. The number of degrees can be determined by using a ratio of marine leagues to degrees which applies to any sized Earth, or by using a specific marine league applied to the true size of the Earth.

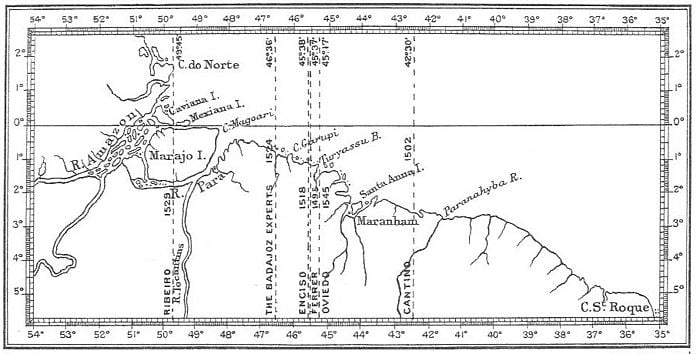

- The earliest Spanish opinion was provided by Jaime Ferrer in 1495, to the Spanish king and queen, at their request. He stated that the demarcation line was 18° west of the most central island of the Cape Verde Islands, which is Fogo according to Harrisse, having a longitude of 24°25'W of Greenwich; hence, Ferrer placed the line at 42°25'W on his sphere, which was 21.1 percent larger than the modern sphere. Ferrer also stated that his league contained 32 Olympic stades, or 6.15264 km according to Harrisse, thus Ferrer's line was 2,276.5 km west of Fogo at 47°37'W on our sphere.[2]

Redâactual possessions;

Pinkâexplorations, areas of influence and trade and claims of sovereignty;

Blueâmain sea explorations, routes and areas of influence.

The disputed discovery of Australia is not shown.

- The earliest surviving Portuguese opinion is on the Cantino planisphere of 1502. Because its demarcation line was midway between Cape Saint Roque (northeast cape of South America) and the mouth of the Amazon River (its estuary is marked Todo este mar he de agua doçe, "All of this sea is fresh water," and its river is marked Rio grande, "great river"), Harrisse concluded that the line was at 42°30'W on the modern sphere. Harrisse believed the large estuary just west of the line on the Cantino map was that of the Rio Marañhao (this estuary is now the BaÃa de São Marcos and the river is now the Mearim), whose flow is so weak that its gulf does not contain fresh water.[3]

- In 1518, another Spanish opinion was provided by Martin Fernandez de Enciso. Harrisse concluded that Enciso placed his line at 47°24'W on his sphere (7.7 percent smaller than the modern), but at 45°38'W on our sphere using Enciso's numerical data. Enciso also described the coastal features near which the line passed in a very confused manner. Harrisse concluded from this description that Enciso's line could also be near the mouth of the Amazon between 49° and 50°W.[4]

- In 1524, the Spanish pilots (ships' captains) Thomas Duran, Sebastian Cabot (son of John Cabot), and Juan Vespuccius (nephew of Amerigo Vespucci) gave their opinion to the Badajoz Junta, whose failure to resolve the dispute led to the Treaty of Zaragoza (1529). They specified that the line was 22° plus nearly 9 miles west of the center of Santo Antão (the westernmost Cape Verde island), which Harrisse concluded was 47°17'W on their sphere (3.1 percent smaller than the modern) and 46°36'W on the modern sphere.[5]

- In 1524, the Portuguese presented a globe to the Badajoz Junta on which the line was marked 21°30' west of Santo Antão (22°6'36" on the modern sphere).[6]

Anti-meridian

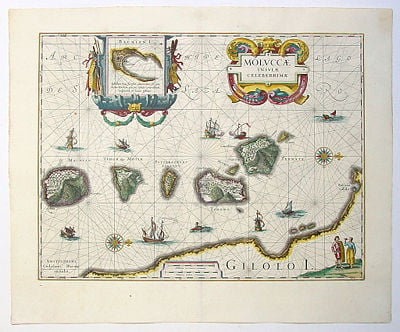

Initially, the line of demarcation did not encircle the Earth. Instead, Spain and Portugal could conquer any new lands they were the first to discover, Spain to the west and Portugal to the east, even if they passed each other on the other side of the globe.[7] But Portugal's discovery of the highly-valued Moluccas in 1512, caused Spain to argue, in 1518, that the Treaty of Tordesillas divided the Earth into two equal hemispheres. After the surviving ships of Magellan's fleet visited the Moluccas in 1521, Spain claimed that those islands were within its western hemisphere. In 1523, the Treaty of Vitoria called for a meeting of the Badajoz Junta in 1524, at which the two countries tried to reach an agreement on the anti-meridian but failed. They finally agreed via the 1529 Treaty of Saragossa (or Zaragoza) that Spain would relinquish its claims to the Moluccas upon the payment of 350,000 ducats of gold by Portugal to Spain. To prevent Spain from encroaching upon Portugal's Moluccas, the anti-meridian was to be 297.5 leagues, or 17°, to the east of the Moluccas, passing through the islands of las Velas and Santo Thome.[8] This distance is slightly smaller than the 300 leagues determined by Magellan as the westward distance from los Ladrones to the Philippine island of Samar, which is just west of due north of the Moluccas.[9]

The Moluccas are a group of islands just west of New Guinea. However, unlike the large modern Indonesian archipelago of the Maluku Islands, to sixteenth century Europeans, the Moluccas were a small chain of islands, the only place on Earth where cloves grew, just west of the large north Malukan island of Halmahera (called Gilolo at the time). Cloves were so prized by Europeans for their medicinal uses that they were worth their weight in gold.[10] Sixteenth and seventeenth century maps and descriptions indicate that the main islands were Ternate, Tidore, Moti, Makian, and Bacan; the last was often ignored even though it was by far the largest island.[11]

The principal island was Ternate, at the chain's northern end (0°47'N, only 11 km (7 mi) in diameter) on whose southwest coast the Portuguese built a stone fort (São João Bautista) during 1522â23,[12] which could only be repaired, not modified, according to the Treaty of Saragossa. This north-south chain occupies two degrees of latitude bisected by the equator at about 127°24'E, with Ternate, Tidore, Moti, and Makian north of the equator and Bacan south of it.

Although the treaty's Santo Thome island has not been identified, its "Islas de las Velas" (Islands of the Sails) appear in a 1585 Spanish history of China, on the 1594 world map of Petrus Plancius, on an anonymous map of the Moluccas in the 1598 London edition of Linschoten, and on the 1607 world map of Petro Kærio, identified as a north-south chain of islands in the northwest Pacific, which were also called the "Islas de los Ladrones" (Islands of the Thieves) during that period.[13] Their name was changed by Spain in 1667, to "Islas de las Marianas" (Mariana Islands), which included Guam at their southern end. Guam's longitude of 144°45'E is east of the Moluccas' longitude of 127°24'E by 17°21', which is remarkably close by sixteenth century standards to the Treaty's 17° east. This longitude passes through the eastern end of the main north Japanese island of HokkaidŠand through the eastern end of New Guinea, which is where Frédéric Durand placed the demarcation line.[14] Moriarty and Keistman placed the demarcation line at 147°E by measuring 16.4° east from the western end of New Guinea (or 17° east of 130°E).[15] Despite the treaty's clear statement that the demarcation line passes 17° east of the Moluccas, some sources place the line just east of the Moluccas.[16]

The Treaty of Saragossa did not modify or clarify the line of demarcation in the Treaty of Tordesillas, nor did it validate Spain's claim to equal hemispheres (180° each), so the two lines divided the Earth into unequal hemispheres. Portugal's portion was roughly 191° whereas Spain's portion was roughly 169°. Both portions have a large uncertainty of ±4° due to the wide variation in the opinions regarding the location of the Tordesillas line.

Portugal gained control of all lands and seas west of the Saragossa line, including all of Asia and its neighboring islands so far "discovered," leaving Spain most of the Pacific Ocean. Although the Philippines were not named in the treaty, Spain implicitly relinquished any claim to them because they were well west of the line. Nevertheless, by 1542, King Charles V decided to colonize the Philippines, judging that Portugal would not protest too vigorously because the archipelago had no spices, but he failed in his attempt. King Philip II succeeded in 1565, establishing the initial Spanish trading post at Manila.

Besides Brazil and the Moluccas, Portugal eventually controlled Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, and São Tomé and PrÃncipe in Africa; Goa and Daman and Diu in India; and East Timor and Macau in the Far East.

Notes

- â Davenport, p. 85, 171.

- â Harrisse, p. 91â97, 178â190.

- â Harrisse, p. 100â102, 190â192.

- â Harrisse, p. 103â108, 122, 192â200.

- â Harrisse, p. 138â139, 207â208.

- â Harrisse, p. 207â208.

- â Edward Gaylord Bourne, "Historical Introduction," in Blair.

- â Treaty of Saragossa, in Blair.

- â Lord Stanley of Alderley, The first voyage round the world, by Magellan. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- â Andaya, p. 1-3.

- â Gavan Daws and Marty Fujita, Archipelago: The Islands of Indonesia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), p. 98. ISBN 0520215761

- â Andaya, p. 117.

- â Knowlton, p.341.

- â Le Reseau Asie, The cartography of the Orientals and Southern Europeans in the beginning of the western exploration of South-East Asia from the middle of the XVth century to the beginning of the XVIIth century by Frédéric Durand. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- â San Diego History, Philip II Orders the Journey of the First Manila Galleon. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- â Giampiero Francalanci, et al., Lines in the Sea. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Andaya, Leonard Y. The World of Maluku: Eastern Indonesia in the Early Modern Period. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1993. ISBN 0-8248-1490-8

- Corn, Charles. The Scents of Eden. New York: Kodansha, 1998. ISBN 1568362021

- Cortesao, Armando. "Antonio Pereira and his map of circa 1545." In Geographical Review, 29. 1939, 205-225.

- Davenport, Frances Gardiner. European Treaties bearing on the History of the United States and its Dependencies to 1648. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1917/1967.

- Harrisse, Henry. The Diplomatic History of America: Its first chapter 1452â1493â1494. London: Stevens, 1897.

- Knowlton, Edgar C. "China and the Philippines in El Periquillo Sarniento." In Hispanic Review 31. 1963, 336-347.

External links

All links retrieved May 2, 2023.

- Treaty of Tordesillas, about.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.