Rafael Trujillo

In this Spanish name, the first or paternal surname is Trujillo and the second or maternal family name is Molina.

| Rafael Trujillo | |

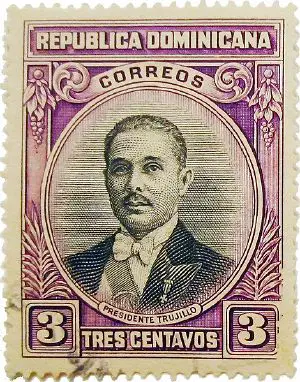

Trujillo in 1930 | |

Generalissimo of the Dominican Republic

| |

| In office 1931 â May 30, 1961 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | Ramfis Trujillo |

President of the Dominican Republic

| |

| In office May 18, 1942 â August 16, 1952 | |

| Vice President(s)  | None |

| Preceded by | Manuel de Jesús Troncoso de la Concha |

| Succeeded by | Héctor Trujillo |

| In office August 16, 1931 â August 16, 1938 | |

| Vice President(s)  | Rafael Estrella Ureña (1930â1932) Vacant (1932â1934) Jacinto Peynado (1934â1938) |

| Preceded by | Rafael Estrella Ureña (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | Jacinto Peynado |

| Born | October 24 1891 San Cristóbal, Dominican Republic |

| Died | May 30 1961 (aged 69) Ciudad Trujillo, Dominican Republic |

| Political party | Dominican Party |

| Spouse | Aminta Ledesma y Pérez (m. 1913; div. 1925) Bienvenida Ricardo y MartÃnez (m. 1927; div. 1935) MarÃa de los Ãngeles MartÃnez y Alba (m. 1937) |

| Relations |

|

| Children | 8, including Ramfis and Angelita[1] |

| Profession |

|

| Signature |

|

Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina (October 24, 1891 â May 30, 1961), nicknamed El Jefe (Spanish: [el Ëxefe]), was a Dominican military commander and dictator who ruled the Dominican Republic from August 1930 until his assassination in May 1961. He served as president from 1930 to 1938 and again from 1942 to 1952, ruling for the rest of his life as an unelected military strongman under figurehead presidents.[2]

His rule of 31 years, known to Dominicans as the Trujillo Era (Spanish: El Trujillato or La Era de Trujillo), was one of the longest for a non-royal leader in the world, and centered around a personality cult of the ruling family. It was also one of the most brutal; Trujillo's security forces, including the infamous SIM, were responsible for perhaps as many as 50,000 murders. These included between 12,000 and 30,000 Haitians in the infamous Parsley massacre in 1937, which continues to affect Dominican-Haitian relations to this day.

Life

Rafael Leónidas Trujillo y Molina was born on October 26, 1891 in San Cristóbal, Dominican Republic, into a lower-middle-class family.[3]

His father was José Trujillo Valdez, the son of Silveria Valdez Méndez of colonial Dominican origin and José Trujillo Monagas, a Canary Islander sergeant who arrived in Santo Domingo as a member of the Spanish reinforcement troops during the Spanish occupation of the Dominican Republic.

Trujillo's mother was Altagracia Julia Molina Chevalier, later known as Mamá Julia, daughter of peasant Pedro Molina Peña, also of colonial Dominican origin, and teacher Luisa Erciná Chevalier, whose parents were of creole Haitian origin.[4][5]

Chevalier, Trujillo's maternal grandmother, was the daughter of Justin Victor Turenne Carrié Blaise, who was of French descent, and Eleonore Juliette Chevallier Moreau, who was part of Haiti's mulatto class. From her mother's side, Chevalier was granddaughter of Louise Moreau and her husband Bernard Chevallier L'Ouverture, a mulatto Haitian high-ranking officer and politician that established in San Cristóbal with the Haitian occupation, from whom countless Dominican families descend, who was the son of French nobleman Jean Baptiste Chevallier, Marquis de Pouilboreau and his wife Marie-Noëlle L'Ouverture, the sister of Toussaint L'Ouverture, the Father of the Nation of Haiti.[4][5]

Trujillo was the third of eleven children;[3][6] he also had an adopted brother, Luis Rafael "Nene" Trujillo (1935â2005), who was raised in the home of Trujillo Molina.[4]

In 1897, at the age of six, Trujillo was registered in the school of Juan Hilario Meriño. One year later, he transferred to the school of Pablo Barinas, where he was educated by disciples of Eugenio MarÃa de Hostos and remained there for the rest of his primary schooling. At the age of 16, Trujillo got a job as a telegraph operator, which he held for about three years.

Shortly after, aided by his brother José Arismendy Petán, he turned to petty crime: cattle rustling, check counterfeiting, and postal robbery. He spent several months in prison, which did not deter him, as he later formed a violent gang of robbers called The 42.[7][8]

Trujillo was married three times and kept other women as mistresses. On August 13, 1913, Trujillo married Aminta Ledesma Lachapelle, with whom he had 2 daughters: Julia, who died as an infant, and Flor de Oro, who died of lung cancer in 1978. On March 30, 1927, Trujillo married Bienvenida Ricardo MartÃnez, a girl from Monte Cristi and the daughter of Buenaventura Ricardo Heureaux, with whom he had a daughter, Odette Trujillo Ricardo. A year later he met MarÃa de los Angeles MartÃnez Alba (nicknamed la españolita, or "the little Spanish girl"), and had an affair with her. He divorced Bienvenida in 1935 and married MartÃnez. A year later

Trujillo's three children with MarÃa MartÃnez were Rafael Leónidas Ramfis, who was born on June 5, 1929, MarÃa de los Ãngeles del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús (Angelita), born in Paris on June 10, 1939, and Leónidas Rhadamés, born on December 1, 1942. Ramfis and Rhadamés were named after characters in Giuseppe Verdi's opera Aida.

In 1937, Trujillo met Lina Lovatón Pittaluga, an upper-class debutante with whom he had two children, Yolanda in 1939, and Rafael, born on June 20, 1943.[9]

Trujillo and his family amassed enormous wealth. He acquired cattle lands on a grand scale, and went into meat and milk production, operations that soon evolved into monopolies. Salt, sugar, tobacco, lumber, and the lottery were other industries which he or his family members dominated. Family members also received positions within the government and the army, including one of Trujillo's sons who was made a colonel in the Dominican Army when he was only four years old.[10] In 1935, Ramfis, then aged 6, was promoted to general. Two of Trujillo's brothers, Héctor and José Arismendy, also held positions in his government.

Over time Trujillo acquired numerous homes. His favorite was Casa Caobas, on Estancia Fundacion near San Cristóbal. He also used Estancia Ramfis (which, after 1953, became the Foreign Office), Estancia Rhadames, and a home at Playa de Najayo. Less frequently he stayed at places he owned in Santiago de los Caballeros, Constanza, La Cumbre, San José de las Matas, and elsewhere. He maintained a penthouse at the Embajador Hotel in the capital.[11]

By 1937 Trujillo's annual income was about $1.5Â million ($32 million in 2023); at the time of his death the state took over 111 Trujillo-owned companies. His love of fine and ostentatious clothing was displayed in elaborate uniforms and suits, of which he collected almost two thousand.[11]

While Trujillo was nominally a Roman Catholic, his devotion was limited to a perfunctory role in public affairs; he placed faith in local folk religion.[11]

On May 30, 1961, he was assassinated by a group of conspirators led by general Antonio Imbert Barrera.

Rise to power

In 1916, the United States began its occupation of the Dominican Republic following 28 revolutions in 50 years.[12] At the time, Trujillo was twenty-five years old and worked as a guarda campestre (overseer) at a sugar cane plantation in Boca Chica.[7] The occupying force soon established a Dominican army constabulary to impose order. Trujillo joined the newly created National Guard in 1918 with the help of his employer along with US Major James J. MacLean, who was his maternal uncle Teódulo Pina Chevalier's friend, and was soon promoted to second lieutenant and began training with the US Marines.[13] Allegations of forgery were ignored when Trujillo applied and he was later acquitted by a panel of Marines following plausible accusations against him, including the alleged rape and subsequent extortion of a 16-year-old girl.[7]

Colonel Richard Malcolm Cutts trained Trujillo further and many Marine leaders praised his abilities at the time, approving his rise among the ranks. He was promoted to lieutenant in 1919 and assigned to the San Pedro de MacorÃs garrison; he was later promoted to captain in 1922 while stationed in San Francisco de MacorÃs and given command of the National Guard 10th Company. In 1923 he was promoted to major and appointed Inspector of the 1st military district.[7]

President Horacio Vásquez named Trujillo the commander of the National Police in 1924, he was named brigadier general in 1928, Trujillo reconstituted the police into the army and created it as an independent armed body under his control.[7] A rebellion or coup d'état against President Vásquez broke out in February 1930 in Santiago. Trujillo secretly cut a deal with the rebel leader Rafael Estrella Ureña. In return for Trujillo letting Estrella take power, Estrella would allow Trujillo to run for president in new elections. As the rebels marched toward Santo Domingo, Vásquez ordered Trujillo to suppress them. However, feigning "neutrality," Trujillo kept his men in barracks, allowing Estrella's rebels to take the capital virtually unopposed. On March 3, Estrella was proclaimed acting president, with Trujillo confirmed as head of the police and of the army. As per their agreement, Trujillo became the presidential nominee of the Patriotic Coalition of Citizens (Spanish: Coalición patriotica de los ciudadanos), with Estrella as his running mate.[10] The other candidates became targets of harassment by the army. When it became apparent that the army would allow only Trujillo to campaign unhindered, the other candidates pulled out. Ultimately, the Trujillo-Estrella ticket was proclaimed victorious with an implausible 99 percent of the vote. In a note to the State Department, American ambassador Charles Boyd Curtis wrote that Trujillo received far more votes than there were actual voters.[10] Upon taking office on August 16, Truijllo assumed dictatorial powers which he retained for the next three decades.

In government

Two and a half weeks after Trujillo ascended to the presidency, the destructive Hurricane San Zenón hit Santo Domingo and left 2000 dead. As a response to the disaster, Trujillo placed the Dominican Republic under martial law and began to rebuild the city. He renamed the rebuilt capital of the Dominican Republic, Ciudad Trujillo ("Trujillo City") in his honor and had streets, monuments, and landmarks to honor him throughout the country.[3]

On August 16, 1931, the first anniversary of his inauguration, Trujillo made the Dominican Party, founded two weeks earlier, the nation's sole legal political party. However, the country had effectively become a one-party state with Trujillo's inauguration. Government employees were required by law to "donate" 10 percent of their salaries to the national treasury[14][15] and there was strong pressure on adult citizens to join the party. Members had to carry a membership card, nicknamed the "Palmita" since the cover had a palm tree on it, and a person could be arrested for vagrancy without one. Those who did not join or contribute to the party did so at their own risk. Opponents of the régime were mysteriously killed.

In 1934, Trujillo, who had promoted himself to generalissimo of the army, was up for re-election. By then, there was no organized opposition left in the country, and he was elected as the sole candidate on the ballot. In addition to the widely rigged (and regularly uncontested) elections, he instated "civic reviews" with large crowds shouting their loyalty to the government, which would in turn create more support for Trujillo.[14]

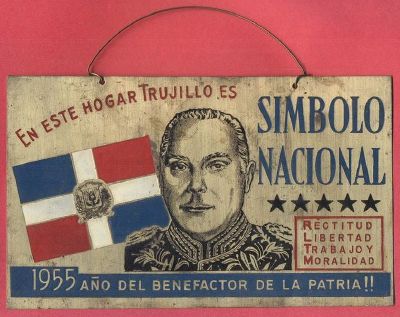

In 1936, at the suggestion of Mario FermÃn Cabral, the Congress of the Dominican Republic voted overwhelmingly to change the name of the capital from Santo Domingo to Ciudad Trujillo. The province of San Cristóbal was renamed to "Trujillo" and the nation's highest peak, Pico Duarte to Pico Trujillo. Statues of "El Jefe" were mass-produced and erected across the Dominican Republic, and bridges and public buildings were named in his honor. The nation's newspapers had praise for Trujillo as part of the front page, and license plates included slogans such as "¡Viva Trujillo!" and "Año del Benefactor de la Patria" (Year of the Benefactor of the Nation). An electric sign was erected in Ciudad Trujillo so that "Dios y Trujillo" could be seen at night as well as in the day. Eventually, even churches were required to post the slogan "Dios en el cielo, Trujillo en la tierra" (God in Heaven, Trujillo on Earth). As time went on, the order of the phrases was reversed (Trujillo on Earth, God in Heaven). Trujillo was recommended for the Nobel Peace Prize by his admirers, but the committee declined the suggestion.[7]

Trujillo was eligible to run again in 1938, but, citing the United States example of two presidential terms, he stated, "I voluntarily, and against the wishes of my people, refuse re-election to the high office."[14] In fact, a vigorous re-election campaign had been launched in the middle of 1937 but the international uproar that followed the Haitian massacre later that year forced Trujillo to announce his "return to private life."[10] Consequently, the Dominican Party nominated Trujillo's handpicked successor, 61-year-old vice-president Jacinto Peynado, with Manuel de Jesús Troncoso his running mate. They appeared alone on the ballot in the 1938 election. Trujillo kept his positions as generalissimo of the army and leader of the Dominican Party. It was understood that Peynado was merely a puppet, and Trujillo still held all governing power in the nation. Peynado died on March 7, 1940, with Troncoso serving out the rest of the term.

However, in 1942, with US President Franklin Roosevelt having run for a third term in the United States, Trujillo ran for president again and was elected unopposed. He served for two terms, which he lengthened to five years each. In 1952, under pressure from the Organization of American States, he ceded the presidency to his brother, Héctor. Despite being officially out of power, Rafael Trujillo organized a major national celebration to commemorate 25 years of his rule in 1955. Gold and silver commemorative coins were minted with his image.[16]

Oppression

Brutal oppression of actual or perceived members of the opposition was the key feature of Trujillo's rule from the very beginning in 1930 when his gang, "The 42," led by Miguel Angel Paulino, drove through the streets in their red Packard "carro de la muerte" ("car of death").[11] Trujillo also maintained an execution list of people throughout the world who he felt were his direct enemies or who he felt had wronged him. He even once allowed an opposition party to form and permitted it to operate legally and openly, mainly so that he could identify those who opposed him and arrest or kill them.[17]

Imprisonments and killings were later handled by the SIM, the Servicio de Inteligencia Militar, efficiently organized by Johnny Abbes, who operated in Cuba, Mexico, Guatemala, New York, Costa Rica, and Venezuela.[18] Some cases reached international notoriety such as the disappearance of Jesús de GalÃndez and the murder of the Mirabal sisters, which further eroded Trujillo's critical support by the US government.

In April 1962, after the flight of the Trujillo family from the country, Attorney General Eduardo Antonio Garcia Vasquez reported that in the previous five years, the former regime was responsible for 5,700 deaths, either as known murders, or of those missing but presumed dead. The SIM often denied victims' families the remains of their loved ones, disposing of them clandestinely. In the aftermath of Trujillo's assassination, very few of those arrested and killed in the subsequent crackdown had their remains returned. What happened to the majority is a mystery, although investigators believed many were tossed to sharks, or were put in an incinerator at nearby San Isidro airbase.[19]

Immigration

Trujillo was known for his open-door policy, accepting Jewish refugees from Europe, Japanese migration during the 1930s, and exiles from Spain following its civil war. At the 1938 Ãvian Conference the Dominican Republic was the only country willing to accept many Jews and offered to accept up to 100,000 refugees on generous terms.[11]

Refugees from Europe broadened the Dominican Republic's tax base and added more whites to the predominantly mixed-race nation. Trujillo's government favored white refugees over others while Dominican troops expelled illegal immigrants, resulting in the 1937 Parsley Massacre of Haitian migrants.

Environmental policy

The Trujillo regime greatly expanded the Vedado del Yaque, a nature reserve around the Yaque del Sur River. In 1934 he banned the slash-and-burn method of clearing land for agriculture, set up a forest warden agency to protect the park system, and banned the logging of pine trees without his permission. In the 1950s the Trujillo regime commissioned a study on the hydroelectric potential of damming the Dominican Republic's waterways. The commission concluded that only forested waterways could support hydroelectric dams, so Trujillo banned logging in potential river watersheds.

After his assassination in 1961, logging resumed in the Dominican Republic. Squatters burned down the forests for agriculture, and logging companies clear-cut parks. In 1967, President JoaquÃn Balaguer launched military strikes against illegal logging.[15]

Trujillo encouraged foreign investment in the Dominican Republic, particularly from Americans. He gave a concession with mineral rights in the Azua Basin to Clem S. Clarke, an oilman from Shreveport, Louisiana.[20]

Foreign policy

During his long rule, the Trujillo government's extensive use of state terrorism was prolific even beyond national borders, including the attempted assassination of Venezuelan President Rómulo Betancourt in 1960 and the abduction and disappearance in New York City of the Basque exile Jesús GalÃndez in 1956.[21] These acts eroded relations between the Dominican Republic and the international community and ushered in Organization of American States (OAS) sanctions and economic and military assistance to Dominican opposition forces.

Trujillo tended toward peaceful coexistence with the United States government. During World War II, Trujillo symbolically sided with the Allies and declared war on Germany, Italy and Japan on December 11, 1941. While there was no military participation, the Dominican Republic thus became a founding member of the United Nations. Trujillo encouraged diplomatic and economic ties with the United States, but his policies often caused friction with other nations of Latin America, especially Costa Rica and Venezuela. He maintained friendly relations with Franco of Spain,[22] Perón of Argentina, and Somoza of Nicaragua. Towards the end of his rule, his relationship with the United States deteriorated.

HullâTrujillo Treaty

Early on, Trujillo determined that Dominican financial affairs had to be put in order, and that included ending the United States' role as collector of Dominican customsâa situation that had existed since 1907 and was confirmed in a 1924 convention signed at the end of the occupation.

Negotiations started in 1936 and lasted four years. On September 24, 1940, Trujillo and the American Secretary of State Cordell Hull signed the HullâTrujillo Treaty, whereby the United States relinquished control over the collection and application of customs revenues, and the Dominican Republic committed to deposit consolidated government revenues in a special bank account to guarantee repayment of foreign debt. The government was free to set custom duties with no restrictions.[23]

This diplomatic success gave Trujillo the occasion to launch a massive propaganda campaign that presented him as the savior of the nation. A law proclaimed that the Benefactor was also now the Restaurador de la independencia financiera de la Republica (Restorer of the Republic's financial independence).[23]

Haiti

Haiti formerly occupied what is today called the Dominican Republic for 22 years - from 1822 to 1844. Prior to their occupation, Spanish colonial rule prevailed. Encroachment by Haiti was an ongoing process, and when Trujillo took over, specifically the northwestern border region had become increasingly "Haitianized."[11] The border was poorly defined. In 1933, and again in 1935, Trujillo met the Haitian President Sténio Vincent to settle the border issue. By 1936, they reached and signed a settlement. At the same time, Trujillo plotted against the Haitian government by linking up with General Calixte, Commander of the Garde d'Haiti, and Ãlie Lescot, at that time the Haitian ambassador in Ciudad Trujillo (Santo Domingo).[11] After the settlement, when further border incursions occurred, Trujillo initiated the Parsley Massacre.

Parsley massacre

Known as La Masacre del Perejil in Spanish, the massacre was started by Trujillo in 1937. Claiming that Haiti was harboring his former Dominican opponents, he ordered an attack on the border that slaughtered tens of thousands of Haitians as they tried to escape. The number of dead is still unknown, but it is now calculated between 12,000 and 30,000.[23]

Anyone of African descent found incapable of pronouncing correctly, that is, to the complete satisfaction of the sadistic examiners, became a condemned individual. This killing is recorded as having a death toll reaching thirty thousand innocent souls, Haitians as well as Dominicans.[24]

The Dominican military used machetes to murder and decapitate many of the victims; they also took people to the port of Montecristi, where many victims were thrown into the sea to drown with their hands and feet bound.[25]

The Haitian response was muted, but its government eventually called for an international investigation. Under pressure from Washington, Trujillo agreed to a reparation settlement in January 1938 of US$750,000. By the next year, the amount had been reduced to US$525,000 (US$9.34Â million in 2025); 30 dollars per victim, of which only two cents were given to survivors because of corruption in the Haitian bureaucracy.[14]

In 1941, Lescot, who had received financial support from Trujillo, succeeded Vincent as President of Haiti. Trujillo expected that Lescot would be his puppet, but Lescot turned against him. Trujillo unsuccessfully tried to assassinate him in a 1944 plot and then published their correspondence to discredit him.[11] Lescot fled into exile in 1946 after demonstrations against him.

Cuba

In 1947, Dominican exiles, including Juan Bosch, had concentrated in Cuba. With the approval and support of Cuba's government, led by Ramón Grau, an expeditionary force was trained with the intention of invading the Dominican Republic and overthrowing Trujillo. However, international pressure, including from the United States, made the exiles abort the expedition.[11] In turn, when Fulgencio Batista was in power, Trujillo initially supported anti-Batista supporters of Carlos PrÃo Socarrás in Oriente Province in 1955; however, weapons Trujillo sent were soon inherited by Fidel Castro's insurgents when PrÃo allied with Castro; Dominican-made Cristóbal carbines and hand grenades became the rebels' standard weapons.

After 1956, when Trujillo saw that Castro was gaining ground, he started to support Batista with money, planes, equipment, and men. Trujillo, convinced that Batista would prevail, was very surprised when Batista showed up as a fugitive after he had been ousted. Trujillo kept Batista until August 1959 as a "virtual prisoner" until he paid US$3â4Â million when he was allowed to leave for Portugal, where he had been granted a visa.[11]

Castro made threats to overthrow Trujillo, and Trujillo responded by increasing the budget for national defense. A foreign legion was formed to defend Haiti, as it was expected that Castro might invade the Haitian part of the island first and remove François Duvalier as well. A Cuban plane with 56 fighting men landed near Constanza, Dominican Republic, on Sunday, June 14, 1959, and six days later more invaders brought by two yachts landed at the north coast. However, the Dominican Army prevailed.[11]

In turn, in August 1959, Johnny Abbes attempted to support an anti-Castro group led by Escambray near Trinidad, Cuba. The attempt, however, was thwarted when Cuban troops surprised a plane he had sent when it was unloading its cargo.[11]

Betancourt assassination attempt

By the late 1950s, opposition to Trujillo's regime was starting to build to a fever pitch, especially among a younger generation who had no memory of the poverty and instability that had preceded the dictatorship. Many clamored for democratization. The Trujillo regime responded with greater repression. The Military Intelligence Service (SIM) secret police, led by Johnny Abbes, remained as ubiquitous as before. Other nations ostracized the Dominican Republic, compounding the dictator's paranoia.

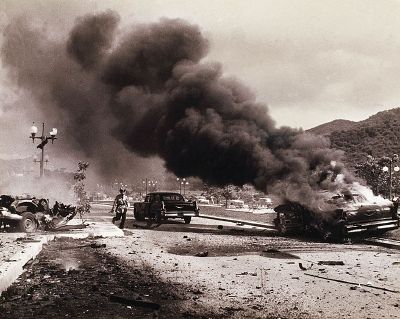

Trujillo began to interfere more and more in the domestic affairs of neighboring countries. He expressed great contempt for Venezuela's president Rómulo Betancourt. An established and outspoken opponent of Trujillo, Betancourt associated with Dominicans who had plotted against the dictator. Trujillo developed an obsessive personal hatred of Betancourt and supported numerous plots by Venezuelan exiles to overthrow him. This pattern of intervention led the Venezuelan government to take its case against Trujillo to the Organization of American States (OAS), a move that infuriated Trujillo, who ordered his agents to plant a bomb in Betancourt's car. The assassination attempt, carried out on Friday, June 24, 1960, injured but did not kill the Venezuelan president.[26]

The Betancourt incident inflamed world opinion against Trujillo. Outraged OAS members voted unanimously to sever diplomatic relations with his government and impose economic sanctions on the Dominican Republic. The brutal murder on Friday, November 25, 1960, of the three Mirabal sisters, Patria, MarÃa Teresa, and Minerva, who opposed Trujillo's dictatorship, further increased discontent with his repressive rule. The dictator had become an embarrassment to the United States, and relations became especially strained after the Betancourt incident.

Assassination

On May 30, 1961, Trujillo was shot and killed when his blue 1957 Chevrolet Bel Air was ambushed on a road outside the Dominican capital. The ambush was plotted by a number of men, including General Juan Tomás DÃaz, Pedro Livio Cedeño, Antonio de la Maza, Amado GarcÃa Guerrero and General Antonio Imbert Barrera.[27]

Aftermath

In the immediate aftermath, Trujillo's son Ramfis took temporary control of the country, executing most of the conspirators. By November 1961, the Trujillo family was pressured into exile by the titular president JoaquÃn Balaguer, who introduced reforms to open up the regime. The murder ushered in civil strife which concluded with the Dominican Civil War and a US-OAS intervention, eventually stabilized under a multi-party system in 1966.

The plotters failed to take control, as the later-executed General José René Román Fernandez ("Pupo Román") betrayed his co-conspirators by his inactivity, and contingency plans had not been made.[8] On the other side, Johnny Abbes, Roberto Figueroa Carrión, and the Trujillo family put the SIM to work to hunt the members of the plot and brought back Ramfis Trujillo from Paris to step into his father's shoes. The response by the SIM was swift and brutal. Hundreds of suspects were detained, many tortured. On 18 November the last executions took place when six of the conspirators were executed in the "Hacienda MarÃa Massacre."[8] Imbert was the only one of the seven assassins who survived the manhunt.[27]

Trujillo's funeral was that of a statesman with the long procession ending in his hometown of San Cristóbal, where his body was first buried. Dominican President JoaquÃn Balaguer gave the eulogy. The efforts of the Trujillo family to keep control of the country ultimately failed. The military uprising on November 19 of the Rebellion of the Pilots and the threat of US intervention set the final stage and ended the Trujillo regime.[8] Ramfis tried to flee with his father's body aboard his boat Angelita, but was turned back. Balaguer allowed Ramfis to leave the country and to take his father's body to Paris. There, the remains were interred in the Cimetière du Père Lachaise on August 14, 1964, and six years later moved to Spain, to the Mingorrubio Cemetery in El Pardo on the north side of Madrid.[28]

United States' involvement

The role of the United States' Central Intelligence Agency in the killing has been debated. Imbert insisted that the plotters acted on their own, although weapons left in the US Consulate after the withdrawal of embassy staff, handed over with CIA approval, were involved in the attack.[27]

However, US involvement may have gone beyond supplying weapons. After efforts to remove Trujillo peacefully failed, plans were activated to effect the removal of Trujillo by any means necessary. Weapons were supplied to the dissidents. After the Bay of Pigs disaster, the Kennedy administration tried to convince the dissidents not to kill Trujillo, to no avail. The assassination was carried out.[29]

Legacy

Trujillo's tyranny, historically known as "La Era de Trujillo" or "The Trujillo Era," is considered one of the bloodiest of the twentieth century, as well as a time of a classic personality cult, with an abundance of monuments to Rafael Trujillo. The Trujillo era unfolded in a Hispanic Caribbean environment particularly susceptible to dictators. Jésus de Galindez points out in the introduction of his book The Era of Trujillo that "In this summer of 1955, half the Latin American republics are ruled by dictatorships, most of them of the military type."[10] In the countries of the Caribbean Basin alone, Trujillo's dictatorship overlapped with those in Cuba, Nicaragua, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Venezuela and Haiti. In that context, the Trujillo dictatorship has been judged more prominent and more brutal than its contemporaries.[23]

Trujillo remains a polarizing figure in the Dominican Republic, as the sheer longevity of his rule makes a detached evaluation difficult. Trujillo reorganized the state and the economy and left a vast infrastructure to the country, but personal freedoms and rights were virtually nonexistent, and the democracy and politics suffered under his regime. His legacy of brutality against his own nation is felt into the present era. Critics denounce the heavy-handed and violent nature of his regime, including the murder of tens of thousands, his open racism and xenophobia towards Haitians, as well as the Trujillo family's nepotism, widespread corruption, and looting of the country's natural and economic resources.

On the other hand, his supporters credit him with bringing long-term stability, economic growth and prosperity, doubling the life expectancy of average Dominicans, and multiplying the GDP.[30]

Trujillo received several important honors, including the Légion d'honneur[31]

Notes

- â Edwin Rafael Espinal Hernández, Descendencias Presidenciales: Trujillo Instituto Dominicano de GenealogÃa, February 21, 2009. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- â Rafael Estrella from March 3, 1930 to August 16, 1930; Jacinto Peynado from August 16, 1938 to March 7, 1940; Manuel Troncoso from March 7, 1940 to May 18, 1942; Héctor Trujillo from August 16, 1952 to August 3, 1960; JoaquÃn Balaguer from August 3, 1960 until January 16, 1962, 8 months after Trujillo's death.

- â 3.0 3.1 3.2 Rafael Trujillo History.com, March 8, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- â 4.0 4.1 4.2 Antonio José Ignacio Guerra Sánchez, Trujillo: Descendiente de la OligarquÃa Haitiana (1 de 2) Instituto Dominicano de GenealogÃa, April 12, 2008. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- â 5.0 5.1 Antonio José Ignacio Guerra Sánchez, Trujillo, descendiente de oligarquÃa haitiana (2 de 2) Instituto Dominicano de GenealogÃa, April 19, 2008. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- â His siblings were Virgilio Trujillo (July 24, 1887 â July 29, 1967), Flérida Marina Trujillo (August 10, 1888 â February 13, 1976), Rosa MarÃa Julieta Trujillo (April 5, 1893 â October 23, 1980), José Arismendy "Petán" Trujillo (October 4, 1895 â May 6, 1969), Amable Romero "Pipi" Trujillo (August 14, 1896 â September 19, 1970), Luisa Nieves Trujillo (August 4, 1899 â January 25, 1977), Julio AnÃbal "Bonsito" Trujillo (October 16, 1900 â December 2, 1948), Pedro Vetilio "Pedrito" Trujillo (January 27, 1902 â March 14, 1981), Ofelia Japonesa Trujillo (May 26, 1905 â February 4, 1978) and Héctor Bienvenido "Negro" Trujillo (April 6, 1908 â October 19, 2002).

- â 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Eric Paul Roorda, The Dictator Next Door: The Good Neighbor Policy and the Trujillo Regime in the Dominican Republic, 1930â1945 (Duke University Press Books, 1998, ISBN 978-0822322344).

- â 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Bernard Diederich, Trujillo, The Death of the Goat (Little Brown & Company, 1978, ISBN 978-0370102863).

- â Rafael Trujillo: President of the Dominican Republic The Robinson Library, September 5, 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- â 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Jesus de Galindez, The Era of Trujillo: Dominican Dictator (University of Arizona Press, 1973, ISBN 978-0816503933).

- â 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 Robert D. Crassweller, The Life and Times of a Caribbean Dictator (Plunkett Lake Press, 2023, ASIN B0BTGNC5R1).

- â Thomas Ayres A Military Miscellany: From Bunker Hill to Baghdad (Bantam, 2006, ISBN 978-0553804409).

- â Suzanne Oboler and Deena J. González (eds.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States (Oxford University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0195156003).

- â 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Maxine Block and E. Mary Trow (eds.), Current Biography Who's News and Why (The H. W. Wilson Company, 1942, ISBN 978-0824204792).

- â 15.0 15.1 Jared Diamond, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed (Penguin Books, 2011, ISBN 978-0143117001).

- â Lauren H. Derby, The Dictator's Seduction: Politics and the Popular Imagination in the Era of Trujillo (Duke University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0822344827).

- â Bernard Spindel, The Ominous Ear (Award House, 1968).

- â Moira Fradinger, Binding Violence: Literary Visions of Political Origins (Stanford University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0804763301).

- â Dominican Republic: Chambers of Horror TIME (April 13, 1962). Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- â Clem S. Clarke, Allan Nevins, and Frank Ernest Hill, Reminiscences of Clem S. Clarke: Oral history, 1951 (Columbia University, 1951).

- â Stuart A. McKeever, Professor GalÃndez: Disappearing from Earth (New York, NY: CUNY Dominican Studies Institute, 2018, ISBN 978-1984913548).

- â Trujillo y Franco, la alianza de dos generalÃsimos Hoy, January 7, 2006. Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- â 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Lauro Capdevila, La Dictature de Trujillo, République dominicaine, 1930â1961 (Paris: L'Harmattan, 1998, ISBN 978-2738468666).

- â Alan Cambeira, Quisqueya la Bella: Dominican Republic in Historical and Cultural Perspective (Routledge, 1996, ISBN 978-1563249358).

- â Javier A. Galván, Latin American Dictators of the 20th Century: The Lives and Regimes of 15 Rulers (McFarland & Company, 2013, ISBN 978-0786466917).

- â Francisco Suniaga, El atentado a Rómulo Betancourt Prodavinci (August 5, 2018). Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- â 27.0 27.1 27.2 I shot the cruellest dictator in the Americas BBC News (May 28, 2011). Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- â Eddy Castellanos, Solitaria, en cementerio poco importante, está la tumba de Trujillo Almomento (April 11, 2008). Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- â Peter Kross, The CIA Assassination of Rafael Trujillo Military Heritage (November 2013). Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- â Jan Knippers Black, Development and Dependency in the Dominican Republic Third World Quarterly 8(1) (January, 1986): 236-257. Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- â U.S., TIME (July 24, 1939). Retrieved July 9, 2024.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ayres, Thomas. A Military Miscellany: From Bunker Hill to Baghdad. Bantam, 2006. ISBN 978-0553804409

- Block, Maxine, and E. Mary Trow (eds.). Current Biography Who's News and Why. The H. W. Wilson Company, 1942. ISBN 978-0824204792

- Cambeira, Alan. Quisqueya la Bella: Dominican Republic in Historical and Cultural Perspective. Routledge, 1996. ISBN 978-1563249358

- Capdevila, Lauro. La Dictature de Trujillo, République dominicaine, 1930â1961. Paris: L'Harmattan, 1998. ISBN 978-2738468666

- Clarke, Clem S., Allan Nevins, and Frank Ernest Hill. Reminiscences of Clem S. Clarke: Oral history, 1951. Columbia University, 1951. OCLC 122308295

- Crassweller, Robert D. The Life and Times of a Caribbean Dictator. Plunkett Lake Press, 2023. ASIN B0BTGNC5R1

- Derby, Lauren H. The Dictator's Seduction: Politics and the Popular Imagination in the Era of Trujillo. Duke University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0822344827

- Diamond, Jared. Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. Penguin Books, 2011. ISBN 978-0143117001

- Diederich, Bernard. Trujillo, The Death of the Goat. Little Brown & Company, 1978. ISBN 978-0370102863

- Fradinger, Moira. Binding Violence: Literary Visions of Political Origins. Stanford University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0804763301

- Galindez, Jesus de. The Era of Trujillo: Dominican Dictator. University of Arizona Press, 1973. ISBN 978-0816503933

- Galván, Javier A. Latin American Dictators of the 20th Century: The Lives and Regimes of 15 Rulers. McFarland & Company, 2013. ISBN 978-0786466917

- McKeever, Stuart A. Professor GalÃndez: Disappearing from Earth. New York, NY: CUNY Dominican Studies Institute, 2018. ISBN 978-1984913548

- Oboler, Suzanne, and Deena J. González (eds.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States. Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0195156003

- Roorda, Eric Paul. The Dictator Next Door: The Good Neighbor Policy and the Trujillo Regime in the Dominican Republic, 1930â1945. Duke University Press Books, 1998. ISBN 978-0822322344

- Spindel, Bernard. The Ominous Ear. Award House, 1968. ASIN B0006BUXH8

External links

All links retrieved July 2, 2024.

- Rafael Trujillo History.com

- About Trujillo Chicago Public Library

- Biography of Rafael Trujillo, "Little Caesar of the Caribbean" ThoughtCo

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Rafael Estrella (acting) |

President of the Dominican Republic 1930â1938 |

Succeeded by: Jacinto Bienvenido Peynado |

| Preceded by: Manuel de Jesús Troncoso de la Concha |

President of the Dominican Republic 1942â1952 |

Succeeded by: Héctor Trujillo |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.