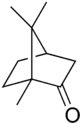

Camphor

| Camphor[1][2] | |

|---|---|

| |

| IUPAC name | 1,7,7-trimethylbicyclo [2.2.1]heptan-2-one |

| Other names | 2-bornanone, 2-camphanone bornan-2-one, Formosa |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | [76-22-2] (unspecified) [464-49-3] ((1R)-Camphor) [464-48-2] ((1S)-Camphor} |

| RTECS number | EX1260000 (R) EX1250000 (S) |

| SMILES | O=C1CC2CCC1(C)C2(C)(C) |

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | C10H16O |

| Molar mass | 152.23 |

| Appearance | White or colorless crystals |

| Density | 0.990 (solid) |

| Melting point |

179.75 °C (452.9 K) |

| Boiling point |

204 °C (477 K) |

| Solubility in water | 0.12 g in 100 ml |

| Solubility in chloroform | ~100 g in 100 ml |

| Chiral rotation [α]D | +44.1° |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | flammable |

| NFPA 704 |

|

| R-phrases | 11-20/21/22-36/37/38 |

| S-phrases | 16-26-36 |

| Related Compounds | |

| Related ketone | fenchone,thujone |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) | |

Camphor is a waxy, white or transparent solid with a strong, aromatic odor.[3] Chemically, it is classified as a terpenoid, and its chemical formula is C10H16O. It is found in the bark and wood of the camphor laurel tree and other related trees of the laurel family. It can also be synthetically produced from oil of turpentine. It is used for its scent, as an ingredient in cooking (mainly in India), as an embalming fluid, and for medicinal purposes. It is also used in some religious ceremonies.

If ingested in relatively large quantities, camphor is poisonous, leading to seizures, confusion, irritability, and even death.

Etymology and history

The word camphor derives from the French word camphre, itself from Medieval Latin camfora, from Arabic kafur, from Malay kapur Barus meaning "Barus chalk." In fact Malay traders from whom Indian and Middle East merchants would buy camphor called it kapur, "chalk" because of its white color.[4] Barus was the port on the western coast of the Indonesian island of Sumatra where foreign traders would call to buy camphor. In the Indian language Sanskrit, the word karpoor is used to denote Camphore. An adaptation of this word, karpooram, has been used for camphor in many South Indian (Dravidian) languages, such as Telugu, Tamil, Kannada, and Malayalam.

Camphor was first synthesized by Gustaf Komppa in 1903. Previously, some organic compounds (such as urea) had been synthesized in the laboratory as a proof of concept, but camphor was a scarce natural product with a worldwide demand. The synthesis was the first industrial total synthesis, when Komppa began industrial production in Tainionkoski, Finland, in 1907.

Sources

Camphor is extracted from the bark and wood of the camphor laurel (Cinnamonum camphora), a large evergreen tree found in Asia, particularly, Borneo and Taiwan. It is also obtained from other related trees of the laurel family, notably Ocotea usambarensis, and from the shrub known as camphor basil (Ocimum kilmandscharicum). Chemists have developed methods of synthesizing camphor from other compounds, such as from oil of turpentine.

Other substances derived from trees are sometimes wrongly sold as camphor.

Properties

Purified camphor takes the form of white or colorless crystals, with a melting point of 179.75 °C (452.9 K) and a boiling point of 204 °C (477 K). It is poorly soluble in water, but it is highly soluble in organic solvents such as acetone, acetic acid, diethyl ether, and chloroform.

Norcamphor is a camphor derivative with the three methyl groups replaced by hydrogen atoms.

Chemical reactions

Camphor can undergo various reactions, some of which are given below.

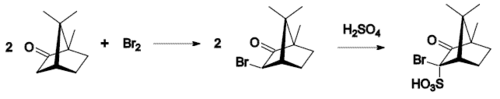

- Bromination:

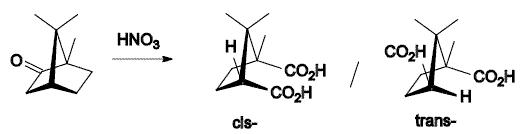

- Oxidation with nitric acid:

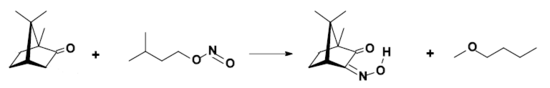

- Conversion to isonitrosocamphor:

- Camphor can also be reduced to isoborneol using sodium borohydride.

Biosynthesis

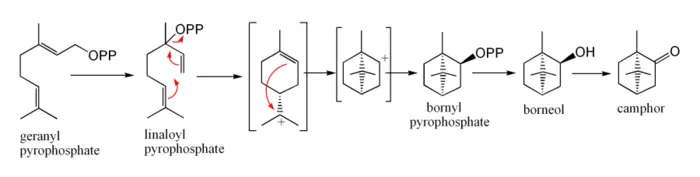

In biosynthesis, camphor is produced from geranyl pyrophosphate. The reactions involve cyclization of linaloyl pyrophosphate to bornyl pyrophosphate, followed by hydrolysis to borneol and oxidation to camphor. The reactions may be written as shown below.

Uses

Currently, camphor is useful for a variety of applications. For instance, it is a moth repellent, an antimicrobial agent, an embalming agent, and a component of fireworks. It is also added as a plasticizer for nitrocellulose. Solid camphor releases fumes that form a rust-preventative coating and is therefore stored in tool chests to protect tools against rust.[5] Camphor is believed to be toxic to insects, and its crystals are used to prevent damage to insect collections by other small insects. The strong odor of camphor is thought to deter snakes and other reptiles.

Recently, carbon nanotubes were successfully synthesized using camphor by a chemical vapor deposition process.[6]

Medical uses

Camphor has several uses in medicine. It is readily absorbed through the skin and produces a cool feeling, similar to that of menthol, and it acts as a slight local anesthetic and antimicrobial substance. A form of anti-itch gel (antipruritic) currently on the market uses camphor as its active ingredient. Camphor is an active ingredient (along with menthol) in vapor-steam products, such as Vicks VapoRub, and it is effective as a cough suppressant. It may also be administered orally in small quantities (50 mg) for minor heart symptoms and fatigue.[7] Camphor is also used in clarifying masks used for the skin.

Culinary uses

Camphor was used as a flavoring in confections resembling ice cream in China during the Tang dynasty (C.E. 618-907). In ancient and medieval Europe, it was widely used as an ingredient for sweets, but it is now mainly used for medicinal purposes in European countries. In Asia, however, it continues to be used as a flavoring for sweets.

In India, camphor is widely used in cooking, mainly for dessert dishes. In South India, it is known as Pachha Karpooram, meaning "green camphor" or "raw camphor." (The latter appears to be the intended meaning, as translated from Tamil.) It is widely available at Indian grocery stores and is labeled as "Edible Camphor." The type of camphor used for Hindu ceremonies is also sold at Indian grocery stores, but it is not suitable for cooking. The only type that should be used for food is that labeled as "Edible Camphor."

Religious ceremonies

In Hindu worship ceremonies (poojas), camphor is burned in a ceremonial spoon for performing aarti. It is used in the Mahashivratri celebrations of Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction and re-creation. As a natural pitch substance, it burns cool without leaving an ash residue, which symbolizes consciousness.

Toxicity

In larger quantities, it is poisonous when ingested and can cause seizures, confusion, irritability, and neuromuscular hyperactivity. In 1980, the United States Food and Drug Administration set a limit of 11 percent allowable camphor in consumer products and totally banned products labeled as camphorated oil, camphor oil, camphor liniment, and camphorated liniment (but "white camphor essential oil" contains no significant amount of camphor). Since alternative treatments exist, medicinal use of camphor is discouraged by the FDA, except for skin-related uses, such as medicated powders, which contain only small amounts of camphor. Lethal, orally ingested doses in adults are in the range 50–500 milligrams per kilogram (mg/kg) of body weight. Generally, two grams (g) causes serious toxicity and four grams is potentially lethal.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Maryadele J. O'Neil (ed.), The Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals, 14th ed. (Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck, ISBN 978-0911910001).

- ↑ David R. Lide (ed.), CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 88th ed.(Boca Raton, FL: CRC, 2007, ISBN 978-0849304880).

- ↑ J. Mann, et al., Natural Products: Their Chemistry and Biological Significance (Harlow, Essex, UK: Longman Scientific & Technical, ISBN 0582060095), 309-311.

- ↑ Camphor Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ↑ Keeping rust off your tools Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ↑ Mukul Kumar and Yoshinori Ando, Carbon Nanotubes from Camphor: An Environment-Friendly Nanotechnology, Journal of Physics Conference Series, (2007) 61: 643–646.

- ↑ Summaries of Product Characteristics (SPC) for Human medicinal products National Agency for Medicines (Finnish).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Lide, David R. (ed.). 2007. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 88th ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC. ISBN 978-0849304880

- Mann, J., et al. 1994. Natural Products: Their Chemistry and Biological Significance. Harlow, Essex, UK: Longman Scientific & Technical. ISBN 0582060095

- O'Neil, Maryadele J. (ed.). 2006. The Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals, 14th ed. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck. ISBN 978-0911910001

- Sell, Charles. 2003. A Fragrant Introduction to Terpenoid Chemistry. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-0854046812

- Smith, Michael, and Jerry March. 2001. March's Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure, 5th ed. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0471585893

External links

All links retrieved November 25, 2023.

- Camphor Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database.

- What is Camphor? wiseGEEK.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.