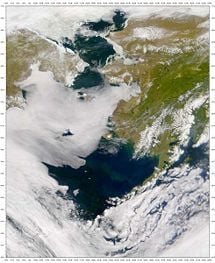

Bering Sea

The Bering Sea is the northernmost part of the Pacific Ocean that comprises a deep water basin (the Aleutian Basin) that rises up through a narrow slope into the shallower water above the continental shelves. Although the Cossack, Semyon Dezhnev, sailed the Sea in 1648, both the Sea and the Strait are named for Vitus Bering, a Danish-born Russian explorer who sailed the Sea in 1728.

The Bering Sea is separated from the Gulf of Alaska by the Alaska Peninsula and Aleutian Islands. Covering about 890,000 square miles (2,304,000 square kilometers), including its islands, it is bordered on the east and northeast by Alaska, on the west by Russia's Siberia and Kamchatka Peninsula, on the south by the Alaska Peninsula and the Aleutian Islands, and on the far north by the Bering Strait which separates the Bering Sea from the Arctic Ocean's Chukchi Sea. Bristol Bay is the portion of the Bering Sea which separates the Alaska Peninsula from mainland Alaska.

The Bering Sea ecosystem includes resources within the jurisdiction of both the United States and Russia, and the boundary between the two nations passes through the Sea and the Strait. The interaction between currents, sea ice, and weather make for a vigorous and productive ecosystem. However, it is a brutal environment, one of the most difficult bodies of water in the world to navigate. In spite of its hazards, the sea contains important shipping routes for the Far East, and fishermen risk their lives there, in one of the most important commercial fishing grounds in the world.

Geography

Ecosystem

The Bering Sea Shelf break is the dominant driver of primary productivity in the Bering Sea.[1] This zone, where the shallower continental shelf drops off into the Aleutian Basin is also known as the âGreenbelt.â Nutrient upwelling from the cold waters of the Aleutian basin flowing up the slope and mixing with shallower waters of the shelf provide for constant production of phytoplankton.

The second driver of productivity in the Bering Sea is seasonal sea ice that, in part, triggers the spring phytoplankton bloom. Seasonal melting of sea ice causes an influx of lower salinity water into the middle and other shelf areas, causing stratification and hydrographic effects which influence productivity.[2] In addition to the hydrographic and productivity influence of melting sea ice, the ice itself also provides an attachment substrate for the growth of algae as well as interstitial ice algae. The productivity associated with sea ice is under threat as global warming causes a reduction of sea ice in the Bering Sea.

Some evidence suggests that great changes to the Bering Sea ecosystem have already occurred. Warm water conditions in the summer of 1997 resulted in a massive bloom of low energy coccolithophorid phytoplankton.[3] A long record of carbon isotopes, which is reflective of primary production trends of the Bering Sea, exists from historical samples of bowhead whale baleen. [4] Trends in carbon isotope ratios in whale baleen samples suggest that a 30-40 percent decline in average seasonal primary productivity has occurred over the last 50 years.[4] The implication is that the carrying capacity of the Bering Sea is much lower now than it has been in the past.

Biodiversity

The Bering Sea is home to some of the world's most interesting wildlife. This sea supports many endangered whale species including bowhead whale, blue whale, fin whale, sei whale, humpback whale, sperm whale, and the rarest whale in the world, the North Pacific Right Whale. Other marine mammals include walrus, Steller's sea lion, Northern Fur Seal, Beluga whales, Orcas (or Killer Whale), and polar bears.

The Bering Sea is very important to the seabirds of the world. Over 30 species of seabirds and approximately 20 million individuals breed in the Bering Sea region. Seabird species include tufted puffins, the endangered Short-tailed Albatross, Spectacled Eider, and Red-legged Kittiwakes. Many of these species are unique to the area, which provides highly productive foraging habitat, particularly along the shelf edge and in other nutrient-rich upwelling regions, such as the Pribilof, Zhemchug, and Pervenets canyons.

Two Bering Sea species, the Steller's Sea Cow (Hydrodamalis gigas) and spectacled cormorant (Phalacrocorax perspicillatus), are extinct because of overexploitation by man. In addition, a small subspecies of Canada goose, the Bering Canada goose (Branta canadensis asiatica) is extinct due to over-hunting and introduction of rats to their breeding islands.

The Bering Sea supports many species of fish. Some fish species support large and valuable commercial fisheries. Commercial fish species include six species of Pacific salmon, walleye pollock, red king crab, Pacific cod, Pacific halibut, yellowfin sole, Pacific ocean perch, and sablefish.

Fish biodiversity is high, and at least 419 species of fish have been reported from the Bering Sea.

Islands

Islands of the Bering Sea include:

- Pribilof Islands

- Komandorski Islands, including Bering Island

- St. Lawrence Island

- Diomede Islands

- King Island

- St. Matthew Island

- Karaginsky Island

Regions of the Bering Sea include

- Bering Strait

- Bristol Bay

The Bering Sea contains 16 submarine canyons including the largest submarine canyon in the world, Zhemchug canyon.

History

Most scientists believe that during the most recent ice age, sea level was low enough to allow humans and other animals to migrate on foot from Asia to North America across what is now the Bering Strait. This is commonly referred to as the "Bering land bridge" and is believed by someâthough not allâto be the first point of entry of humans into the Americas. It is therefore considered a critical focal point for researchers, as it is quite possibly one of the world's great, ancient crossroads, though it provides no written record.

Archaeological evidence seems to indicate that migrations from Asia to the North American continent occurred in three waves: The first migration, between 15,000 and 12,000 years ago, included Paleo-Indians; the second migration occurred at approximately the same time, but it took place along the southern coast of the Beringian land mass and included ancestors of the Eskimo and Aleut peoples; the third migration is thought to have occurred around 12,000 years ago and possibly included the ancestors of the interior Alaska Indians and the Pacific Northwest coast Indians.

Russian ships under Semyon Dezhnyov first explored the Bering Sea and Bering Strait in 1648. Both are named for Vitus Bering, a Danish captain who was taken into Russian service by Peter the Great, in 1724, and who sailed the Sea in 1728. In the eighteenth century Russian and English explorers mapped the Bering Strait and the area to the north.

The area became more popular with the commencement of the great era of New England whaling industry in the mid-nineteenth century. In 1867, the United States government purchased from Russia all her territorial rights in Alaska and the adjacent islands. The boundary between the two countries was a line drawn from the middle of Bering Strait southwest to a point midway between the Aleutian and Komandorski Islands dividing the Bering Sea into two parts, the larger being on the American side. This portion included the Pribilof Islands, the principal breeding-grounds of the seals in those seas. International conflicts over fishing rights ensued, eventually being settled in 1893.

The 1898-99, gold rush to the Seward Peninsula brought prospectors to the region, and communities were established. Proposals were made, for the first time, for an Alaskan-Siberian railroad that would have joined Asia and North America with a rail bridge or tunnel across the Bering Strait, but the project faltered. Similar proposals have re-emerged since the 1990s, this time with the availability of cutting-edge tunneling technology.

Industry

Bering Sea fisheries

Commercial fishing is big business in the Bering Sea, which is relied upon by the largest seafood companies in the world to provide fish and shellfish. It is renowned for its enormously productive and profitable fisheries, such as King Crab,[5] opilio and tanner crabs, Bristol Bay salmon, pollock, and other groundfish.

Bristol Bay, the eastern-most arm of the Bering Sea, is home to the world's largest sockeye salmon fishery as well as strong runs of chum salmon, silver salmon and king salmon, each occurring seasonally. Its associated canneries, sport fishing, hunting and tourism, especially to nearby Katmai National Park and Preserve, are additional sources of commerce.

On the U.S. side, commercial fisheries catch approximately $1 billion worth of seafood annually (half the national catch of fish and shellfish), while Russian Bering Sea fisheries are worth approximately $600 million annually.

These world's fisheries rely on the productivity of the Bering Sea via a complicated and little understood food web. The continued existence of these fisheries requires an intact, healthy and productive ecosystem. Atmospheric and oceanic processes in the Arctic Ocean to the north and the North Pacific Ocean to the south influence the Bering Sea; it shares properties of both and is neither truly polar nor typically north temperate in character. The greatest ecological concern is the warming of Arctic waters and melting of ice.

Oil and mineral development

The area has also experienced significant interest in oil and mineral development, most notably with the proposed Pebble Mine on the north shore of Iliamna Lake, and auctioning of leases to tracts in the southern Bristol Bay area known as the North Aleutians Basin, an area which has been closed to offshore oil and gas development since a moratorium in 1998.[6] There is also a proposal to open most of the BLM's 3.6 million acres (15,000 km²) in the area to hard rock mining and oil and gas drilling.

The Bering Sea is considered one of the most difficult bodies of water in the world to navigate. Severe winter storms coat ships with ice and create powerful waves in excess of forty feet. Decreased visibility due to pelting rain and heavy fog make floating ice difficult to avoid. In spite of these hazards, the sea is an important shipping route for the Far East, including the eastern terminus at Provideniya on the Chukchi Peninsula for the northern sea route to Arkhangelsk in the west.

Notes

- â A.M. Springer, C.P. McRoy, and M.V. Flint, "The Bering Sea green belt: Shelf-edge processes and ecosystem production," Fisheries Oceanography 5: 205-223.

- â J.D. Schumacher, T. J. Kinder, D. J. Pashinski, and R. L. Charnell, "A structural front over the continental shelf of the eastern Bering Sea." Journal Physical Oceanography 9 (1979): 79-87.

- â Dean A. Stockwell, Terry E. Whitledge, Stephan I. Zeeman, Kenneth O. Coyle, Jeffrey M. Napp, Richard D. Brodeur, Alexei I. Pinchuk, and George L. Hunt, "Anomalous conditions in the south-eastern Bering Sea, 1997: nutrients, phytoplankton and zooplankton," Fisheries Oceanography 10 (1): 99-116.

- â 4.0 4.1 D. M. Schell, "Declining carrying capacity in the Bering Sea: isotopic evidence from whale baleen," LIMNOLOGY AND OCEANOGRAPHY 45: 459-462.

- â Alaska Fisheries Science Center, Red King Crab, Paralithodes camtschaticus. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- â Pebble Limited Partnership, Pebble Project. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Loughlin, Thomas R., and Kiyotaka Ohtani. Dynamics of the Bering Sea: A Summary of Physical, Chemical, and Biological Characteristics, and a Synopsis of Research on the Bering Sea. Fairbanks, Alaska: University of Alaska Sea Grant, 1999. ISBN 978-1566120623.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Bering Sea Climate and Ecosystem. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- National Research Council (U.S.), and NetLibrary, Inc. 1996. The Bering Sea Ecosystem. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. ISBN 0309053455

External links

All links retrieved September 28, 2023.

- Barbi Failor-Rounds and Krista Milani. Bering Sea-Aleutian Islands area state-waters groundfish fisheries and groundfish harvest from parallel seasons in 2005 Alaska Dept. of Fish and Game.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.