Battle of Moscow

| Battle of Moscow | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War II | |||||||

December, 1941. Soviet troops in winter gear supported by tanks take on the Germans in the counter-attack. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

Nazi Germany |

Soviet Union | ||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Fedor von Bock, Heinz Guderian |

Georgiy Zhukov, Aleksandr Vasilyevskiy | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| As of October 1: 1,000,000 men, 1,700 tanks, 14,000 guns, 950 planes[1] |

As of October 1: 1,250,000 men, 1,000 tanks, 7,600 guns, 677 planes[2] | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| 248,000–400,000(see §7) | 650,000–1,280,000(see §7) | ||||||

The Battle of Moscow (Russian: Битва за Москву, Romanized: Bitva za Moskvu. German: Schlacht um Moskau) was the Soviet defense of Moscow and the subsequent Soviet counter-offensive that occurred between October 1941 and January 1942 on the Eastern Front of World War II against Nazi forces. Hitler considered Moscow, capital of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) and the largest Soviet city, to be the primary military and political objective for Axis forces in their invasion of the Soviet Union. A separate German plan was codenamed Operation Wotan.

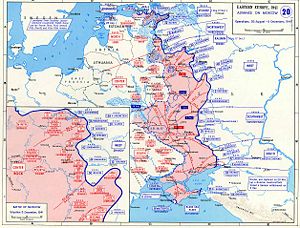

The original blitzkrieg invasion plan, which the Axis called Operation Barbarossa, called for the capture of Moscow within four months. However, despite large initial advances, the Wehrmacht was slowed by Soviet resistance (in particular during the Battle of Smolensk, which lasted from July through September 1941 and delayed the German offensive towards Moscow for two months). Having secured Smolensk, the Wehrmacht chose to consolidate its lines around Leningrad and Kiev, further delaying the drive towards Moscow. The Axis advance was renewed on October 2, 1941, with an offensive codenamed Operation Typhoon, to complete the capture of Moscow before the onset of winter.

After an advance leading to the encirclement and destruction of several Soviet armies, the Soviets stopped the Germans at the Mozhaisk defensive line, just 120 km (75 mi) from the capital. Having penetrated the Soviet defenses, the Wehrmacht offensive was slowed by weather conditions, with autumn rains turning roads and fields into thick mud that significantly impeded Axis vehicles, horses, and soldiers. Although the onset of colder weather and the freezing of the ground allowed the Axis advance to continue, it continued to struggle against stiffening Soviet resistance.

By early December, the lead German Panzer Groups stood less than 30 kilometers (19 mi) from the Kremlin, and Wehrmacht officers were able to see some of Moscow's buildings with binoculars; but the Axis forces were unable to make further advances. On December 5, 1941, fresh Soviet Siberian troops, prepared for winter warfare, attacked the German forces in front of Moscow; by January 1942, the Soviets had driven the Wehrmacht back 100 to 250 km (60 to 150 mi), ending the immediate threat to Moscow and marking the closest that Axis forces ever got to capturing the Soviet capital.

| Eastern Front |

|---|

| Barbarossa – Baltic Sea – Finland – Leningrad and Baltics – Crimea and Caucasus – Moscow – 1st Rzhev-Vyazma – 2nd Kharkov – Blue – Stalingrad – Velikiye Luki – 2nd Rzhev-Sychevka – Kursk – 2nd Smolensk – Dnieper – 2nd Kiev – Korsun – Hube's Pocket – Baltic – Bagration – Lvov-Sandomierz – Lublin-Brest – Balkans (Iassy-Kishinev) – Balkans (Budapest) – Vistula-Oder – East Prussia – East Pomerania – Silesia – Berlin – Prague – Vienna |

The Battle of Moscow was one of the most important battles of World War II, primarily because the Soviets were able to successfully prevent the most serious attempt to capture their capital. The battle was also one of the largest during the war, with more than a million total casualties. It marked a turning point as it was the first time since the Wehrmacht began its conquests in 1939 that it had been forced into a major retreat. The Wehrmacht had been forced to retreat earlier during the Yelnya Offensive in September 1941 and at the Battle of Rostov (1941) (which led to von Rundstedt losing command of German forces in the East), but these retreats were minor compared to the one at Moscow.

Background

- For more details on this topic, see Operation Barbarossa.

On June 22, 1941, German, Hungarian, Romanian and Slovak troops invaded the Soviet Union, effectively starting Operation Barbarossa. Having destroyed most of the Soviet Air Force on the ground, German forces quickly advanced deep into Soviet territory using blitzkrieg tactics. Armored units raced forward in pincer movements, pocketing and destroying entire Soviet armies. While the German Army Group North moved towards Leningrad, Army Group South was to take control of Ukraine, while Army Group Center advanced towards Moscow. The Soviet defenses were overwhelmed and the casualties sustained by the Red Army were significant.

By July 1941, Army Group Center had managed to encircle several Soviet armies near Minsk during the Battle of Białystok-Minsk, creating a huge breach in Soviet lines—one that the Soviets couldn't immediately fill, as no reserves were available—and destroying the Soviet Western Front as an organized force. Thus, the Wehrmacht was able to cross the Dnieper river, which barred the path to Moscow, with only minimal casualties.[3]

In August 1941, German forces captured the city of Smolensk, an important stronghold on the road to Moscow. Smolensk was historically considered as the "key" to Moscow because it controlled a landbridge located between the Dvina, Dnieper, and several other rivers, allowing for a fast advance by ground troops without the necessity of building major bridges across wide rivers. The desperate Soviet defense of the Smolensk region lasted for two months, from July 10, 1941 to September 10, 1941.[4] This intense engagement, known as the Battle of Smolensk, delayed the German advance until mid-September, effectively disrupting the blitzkrieg and forcing Army Group Center to use almost half of its strategic reserves (10 divisions out of 24) during the battle.[4]

Elsewhere, the German advance was also bogged down. Near Leningrad, Army Group North was held up by the Luga defense line for almost a month before eventually overrunning it. In the south, Army Group South—which included many Hungarian and Romanian units that were less well-trained, equipped and experienced than the Wehrmacht—sustained several serious counterattacks, and was stopped. The Wehrmacht now faced a dilemma, as Army Group Center was still strong enough to reach Moscow–but such an advance would create a bulge in the German lines, leaving it vulnerable to Red Army flanking attacks. Moreover, according to Hitler, Germany needed the food and mineral resources located in the Ukraine.[5] Thus, the Wehrmacht was ordered to first secure the Donbass region and to move towards Moscow afterwards.[6] Heinz Guderian's Panzer Army was turned south to support Gerd von Rundstedt's attack on Kiev,[5] which inflicted another significant defeat on the Red Army. On September 19, 1941, Soviet forces had to abandon Kiev after Stalin's persistent refusal to withdraw forces from the Kiev salient, as recorded by Aleksandr Vasilevsky and Georgy Zhukov in their respective memoirs.[7][8] This refusal cost Zhukov his post of Chief of the General Staff,[9] but his prediction of German encirclement was correct. Several Soviet armies were encircled and annihilated by the Wehrmacht in a double pincer movement, allowing the German forces to advance in the south.[10]

While undeniably a decisive Axis victory, the Battle of Kiev set the German blitzkrieg even further behind schedule. As Guderian later wrote, "Kiev was certainly a brilliant tactical success, but the question of whether it had a significant strategic importance still remains open. Everything now depended on our ability to achieve expected results before the winter and even before autumn rains."[11] Hitler still believed that the Wehrmacht had a chance to finish the war before winter by taking Moscow. On October 2, 1941, Army Group Center under Fedor von Bock, launched its final offensive towards Moscow, code-named Operation Typhoon. Hitler said soon after its start that "After three months of preparations, we finally have the possibility to crush our enemy before the winter comes. All possible preparations were done…; today starts the last battle of the year…."[12]

Initial German advance (September 30 – October 10)

Plans

For Hitler, Moscow was the most important military and political target, as he anticipated that the city's surrender would shortly afterwards lead to the general collapse of the Soviet Union. As Franz Halder, head of the Oberkommando des Heeres (Army General Staff), wrote in 1940, "The best solution would be a direct offensive towards Moscow."[2] Thus, the city was a primary target for the large and well-equipped Army Group Center. The forces committed to Operation Typhoon included three armies (the 2nd, 4th and 9th) supported by three Panzer Groups (the 2nd, 3rd and 4th) and by the Luftwaffe's Second Air Fleet. Overall, more than one million men were committed to the operation, along with 1,700 tanks, 14,000 guns, and 950 planes.[1] The attack relied on standard blitzkrieg tactics, using Panzer groups rushing deep into Soviet formations and executing double-pincer movements, pocketing Red Army divisions and destroying them.[13]

The initial Wehrmacht plan called for two initial movements. The first would be a double-pincer performed around the Soviet Western Front and Reserve Front forces located around Vyazma. The second would be a single-pincer around the Bryansk Front to capture the city of Bryansk. From that point, the plan called for another quick pincer north and south of Moscow to encircle the city. However, the German armies were already battered and experiencing some logistical problems. Guderian, for example, wrote that some of his destroyed tanks had not been replaced, and that his mechanized troops lacked fuel at the beginning of the operation.[14]

Facing the Wehrmacht were three Soviet fronts formed from exhausted armies that had already been involved in heavy fighting for several months. The forces committed to the city's defense totaled 1,250,000 men, 1,000 tanks, 7,600 guns and 677 aircraft. However, these troops, while presenting a significant threat to the Wehrmacht based on their numbers alone, were poorly located, with most of the troops deployed in a single line, and had little or no reserves to the rear.[2] In his memoirs, Vasilevsky pointed out that while immediate Soviet defenses were quite well prepared, these errors in troop placement were largely responsible for the Wehrmacht's initial success.[15] Furthermore, many Soviet defenders were seriously lacking in combat experience and some critical equipment (such as anti-tank weapons), while their tanks were obsolete models.[16]

The Soviet command began constructing extensive defenses around the city. The first part, the Rzhev-Vyazma defense setup, was built on the Rzhev-Vyazma-Bryansk line. The second, the Mozhaisk defense line, was a double defense stretching between Kalinin and Kaluga. Finally, a triple defense ring surrounded the city itself, forming the Moscow Defense Zone. These defenses were still largely unprepared by the beginning of the operation due to the speed of the German advance.[2] Furthermore, the German attack plan had been discovered quite late, and Soviet troops were ordered to assume a total defensive stance only on September 27, 1941.[2] However, new Soviet divisions were being formed on the Volga, in Asia and in the Urals, and it would only be a matter of a few months before these new troops could be committed,[17] making the battle a race against time as well.

Vyazma and Bryansk pockets

Near Vyazma, the Western and Reserve fronts were quickly defeated by the highly mobile forces of the 3rd and 4th Panzer groups that exploited weak areas in the defenses and then quickly moved behind the Red Army lines. The defense setup, still under construction, was overrun as both German armored spearheads met at Vyazma on October 10, 1941.[16] Four Soviet armies (the 19th, 20th, 24th and 32nd) were trapped in a huge pocket just west of the city.[18]

Contrary to German expectations, the encircled Soviet forces did not surrender easily. Instead, the fighting was fierce and desperate, and the Wehrmacht had to employ 28 divisions to eliminate the surrounded Soviet armies, using forces that were needed to support the offensive towards Moscow. The remnants of the Soviet Western and Reserve fronts were able to retreat and consolidate their lines around Mozhaisk.[18] Moreover, the surrounded Soviet forces were not completely destroyed, as some of the encircled troops escaped in groups ranging in size from platoons to full rifle divisions.[16] Soviet resistance near Vyazma also provided time for the Soviet high command to quickly bring some reinforcements to the four armies defending the Moscow direction (namely, the 5th, 16th, 43rd and 49th), and to transport three rifle and two tank divisions from the Far East.[18]

In the south near Bryansk, initial Soviet performance was barely more effective than near Vyazma. The Second Panzer Group executed an enveloping movement around the whole front, linking with the advancing 2nd Army and capturing Orel by October 3 and Bryansk by October 6. The Soviet 3rd and 13th armies were encircled but, again, did not surrender, and troops were able to escape in small groups, retreating to intermediate defense lines around Poniry and Mtsensk. By October 23, the last remnants had escaped from the pocket.[2]

By October 7, 1941, the German offensive in this area was bogged down. The first snow fell and quickly melted, turning roads into stretches of mud, a phenomenon known as rasputitsa (Russian: распу́тица) in Russia. German armored groups were greatly slowed and were unable to easily maneuver, wearing down men and tanks.[19] [20]

The 4th Panzer Division fell into an ambush set by Dmitri Leliushenko's hastily formed 1st Guards Special Rifle Corps, including Mikhail Katukov's 4th Tank Brigade, near the city of Mtsensk. Newly built T-34 tanks were concealed in the woods as German panzers rolled past them; as a scratch team of Soviet infantry contained their advance, Soviet armor attacked from both flanks and savaged the German Panzer IV formations. For the Wehrmacht, the shock of this defeat was so great that a special investigation was ordered.[16] Guderian and his troops discovered, to their dismay, that new Soviet T-34s were almost impervious to German tank guns. As the general wrote, "Our T-IV tanks with their short 75 mm guns could only explode a T-34 by hitting the engine from behind." Guderian also noted in his memoirs that "the Russians already learned a few things."[21] Elsewhere, massive Soviet counterattacks had further slowed the German offensive.

The magnitude of the initial Soviet defeat was appalling. According to German estimates, 673,000 soldiers were captured by the Wehrmacht in both pockets,[22] although recent research suggests a somewhat lower, but still enormous figure of 514,000 prisoners, reducing Soviet strength by 41 %.[23] The desperate Red Army resistance, however, had greatly slowed the Wehrmacht. When, on October 10, 1941, the Germans arrived within sight of the Mozhaisk line, they found a well-prepared defensive setup and new, fresh Soviet forces. That same day, Georgy Zhukov was recalled from Leningrad to take charge of the defense of Moscow.[2] He immediately ordered the concentration of all available defenses on a strengthened Mozhaisk line, a move supported by Vasilevsky.[24]

Reportedly, Stalin's first reaction to the German advance on Moscow was to deny the truth and to search for scapegoats for the Soviet defeats. However, once he realized the danger to the capital, the Soviet leader came close to hysteria. On October 13, he ordered the evacuation of the Communist Party, the General Staff and various civil government offices from Moscow to Kuibyshev (now Samara), leaving only a limited number of officials behind. The evacuation caused panic among Moscovites. From October 16 to October 17, much of the civilian population tried to flee, mobbing the available trains and jamming the roads from the city. Despite all this, Stalin publicly remained in the Soviet capital, somewhat calming the fear and pandemonium.[16]

Mozhaisk defense line (October 13 – October 30)

By October 13, 1941, the Wehrmacht had arrived at the Mozhaisk defense line, a hastily constructed double set of fortifications protecting Moscow from the west and stretching from Kalinin towards Volokolamsk and Kaluga. However, despite recent reinforcements, the combined strength of the Soviet armies manning the line (the 5th, 16th, 43rd and 49th armies) barely reached 90,000 men, hardly sufficient to stem the German advance.[25][26] In light of the situation, Zhukov decided to concentrate his forces at four critical points: Volokolamsk, Mozhaisk, Maloyaroslavets and Kaluga. The entire Soviet Western front, almost completely destroyed after its encirclement near Vyazma, was being recreated from scratch.[27]

Moscow itself was transformed into a fortress. According to Zhukov, 250,000 women and teenagers worked, building trenches and anti-tank moats around Moscow, moving almost three million cubic meters of earth with no mechanical help. Moscow's factories were hastily transformed into military complexes: the automobile factory was turned into a submachine gun armory, a clock factory was manufacturing mine detonators, the chocolate factory was producing food for the front, and automobile repair stations were repairing damaged tanks and vehicles.[28] However, the situation was very dangerous, as the Soviet capital was still within reach of German panzers. Additionally, Moscow was now a target of massive air raids, although these caused only limited damage because of extensive anti-aircraft defenses and effective civilian fire brigades.

On October 13, 1941 (October 15, 1941, according to other sources), the Wehrmacht resumed its offensive. At first, the Wehrmacht was unwilling to assault the Soviet defenses directly and attempted to bypass them by pushing northeast towards the weakly protected city of Kalinin, and south towards Kaluga and Tula, capturing all except Tula by October 14. Encouraged by this initial success, the Germans conducted a frontal assault against the fortified line, taking Mozhaisk and Maloyaroslavets on October 18, Naro-Fominsk on October 21, and Volokolamsk on October 27, after intense fighting.[2] Due to the increasing danger of flanking attacks, Zhukov was forced to fall back[16] and withdraw his forces east of the Nara River.[29]

In the south, the Second Panzer Army was moving towards Tula with relative ease, since the Mozhaisk defense line did not extend that far south, and because there were no significant concentrations of Soviet troops to slow down the advance. The bad weather, fuel problems, and damaged roads and bridges greatly slowed the Germans; Guderian reached the outskirts of Tula only by October 26, 1941.[30] The German plan initially called for an instant capture of Tula and for a pincer move around Moscow. However, the first attempt to capture the city failed, as German panzers were stopped by the 50th Army and civilian volunteers in a desperate fight. Guderian's army had to stop within sight of the city on October 29, 1941.[31]

Wehrmacht at the Gates (November 1 – December 5)

Wearing down

By late October the Wehrmacht and the Red Army could be compared to "punch-drunk boxers, staying precariously on their feet but rapidly losing the power to hurt each other." The German forces were worn out, with only a third of their motor vehicles still functioning, infantry divisions at one-third to one-half strength, and serious logistics issues preventing the delivery of warm clothing and other winter equipment to the front. Even Hitler seemed to surrender to the idea of a long struggle, since the prospect of sending tanks into such a large city without heavy infantry support seemed risky after the costly capture of Warsaw in 1939.[32]

To stiffen the resolve of both the Red Army and increasingly demoralized civilians, Stalin ordered the traditional military parade to celebrate the October Revolution on November 7 (new style calendar) to be staged in Red Square. Soviet troops paraded past the Kremlin and then marched directly to the front. However, despite such a brave show, the Red Army was actually in a very precarious position. Although 100,000 additional Soviet troops had reinforced Klin and Tula, where new German offensives were expected, Soviet defenses were still relatively thin. Nevertheless, Stalin wanted several preemptive counteroffensives to be launched against the German lines, despite protests from Zhukov, who pointed out the complete lack of reserves.[33] The Wehrmacht was able to repel most of these counteroffensives, depleting the Red Army of men and vehicles that could have been used for Moscow's defense. The offensive was only successful west of Moscow near Aleksino, where Soviet tanks inflicted heavy losses on the 4th Army because the Germans still lacked anti-tank weapons capable of damaging the new, well-armored T-34 tanks.[32]

Despite the defeat near Aleksino, the Wehrmacht still possessed an overall superiority in men and equipment over the Red Army. The German divisions committed to the final assault on Moscow numbered 943,000 men, 1,500 tanks and 650 planes, while Soviet forces were reduced to a shadow of their former selves, with barely 500,000 men, 890 tanks and 1,000 planes.[2] However, compared to October, Soviet rifle divisions occupied much better defensive positions, a triple defensive ring surrounding the city, and some remains of the Mozhaisk line still in Soviet hands near Klin. Most of the Soviet field armies now had a multilayered defense with at least two rifle divisions in second echelon positions. Artillery support and sapper teams were also concentrated along major roads that German troops were expected to use in their attacks. Finally, Soviet troops—especially officers—were now more experienced and better prepared for the offensive.[32]

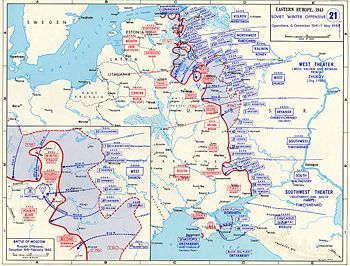

By November 15, 1941, the ground had finally frozen, solving the mud problem. The armored Wehrmacht spearheads were unleashed, with the goal of encircling Moscow and linking up near the city of Noginsk, east of the capital. In order to achieve this objective, the German Third and Fourth Panzer groups needed to concentrate their forces between the Moscow reservoir and Mozhaisk, then proceed to Klin and Solnechnogorsk to encircle the capital from the north. In the south, the Second Panzer Army intended to bypass Tula, still in Soviet hands, and advance to Kashira and Kolomna, linking up with the northern pincer at Noginsk.[2]

Final pincer

On November 15, 1941, German tank armies began their offensive towards Klin, where no Soviet reserves were available due to Stalin's wish to attempt a counteroffensive at Volokolamsk, which had forced the relocation of all available reserves forces further south. Initial German attacks split the front in two, separating the 16th Army from the 30th.[32] Several days of intense combat followed. As Zhukov recalls in his memoirs, "The enemy, ignoring the casualties, was making frontal assaults, willing to get to Moscow by any means necessary."[34] Despite the Wehrmacht's efforts, the multilayered defense reduced Soviet casualties as the Soviet 16th Army slowly retreated and constantly harassed the German divisions trying to make their way through the fortifications.

The Third Panzer Army finally captured Klin after heavy fighting on November 24, 1941, and by November 25, 1941, Solnechnogorsk as well. Soviet resistance was still strong, and the outcome of the battle was by no means certain. Reportedly, Stalin asked Zhukov whether Moscow could be successfully defended and ordered him to "speak honestly, like a communist." Zhukov replied that it was possible, but that reserves were desperately needed.[34] By November 28, the German 7th Panzer Division had seized a bridgehead across the Moscow-Volga Canal—the last major obstacle before Moscow—and stood less than 35 kilometers from the Kremlin;[32] but a powerful counterattack by the Soviet 1st Shock Army drove them back across the canal.[35] Just northwest of Moscow, the Wehrmacht reached Krasnaya Polyana, little more than 20 kilometers from Moscow;[36] German officers were able to make out some of the major buildings of the Soviet capital through their field glasses. However, both Soviet and German forces were severely depleted, sometimes having only 150 to 200 riflemen (a company's full strength) left in a regiment.[32]

In the south, near Tula, hostilities resumed on November 18, 1941, with the Second Panzer army trying to encircle the city.[32] The German forces involved were extremely battered from previous fighting, and still had no winter clothing. As a result, initial German progress was only 5 to 10 km (3 to 6 mi) per day, making chances of success "less than certain" according to Guderian.[37] Moreover, it exposed the German tank armies to flanking attacks from the Soviet 49th and 50th armies, located near Tula, further slowing the advance. However, Guderian was still able to pursue the offensive, spreading his forces in a star-like attack, taking Stalinogorsk on November 22, 1941 and surrounding a Soviet rifle division stationed there. On November 26, German panzers approached Kashira, a city controlling a major highway to Moscow. In response, a violent Soviet counterattack was launched the following day. General Belov's cavalry corps, supported by several rifle brigades and tank groups, halted the German advance near Kashira.[38] The Germans were driven back in early December, securing the southern approach to the city.[39] Tula itself held, protected by fortifications and determined defenders, both soldiers and civilians. In the south, the Wehrmacht never got close to the capital.

Due to the resistance on both the northern and southern sides of Moscow, the Wehrmacht attempted, on December 1, 1941, a direct offensive from the west, along the Minsk-Moscow highway near the city of Naro-Fominsk. However, this attack had only limited tank support and was forced to assault extensive Soviet defenses. After meeting determined resistance from the Soviet 1st Guards Motorized Rifle Division and flank counterattacks staged by the 33rd Army, the German offensive was driven back four days later,[32] with the Germans losing 10,000 men and several dozen tanks.[40]

By early December, the temperatures, so far relatively mild by Russian standards,[41] dropped as low as 20 to 50 degrees Celsius below zero, freezing German troops, who still had no winter clothing, and German vehicles, which were not designed for such severe weather. More than 130,000 cases of frostbite were reported among German soldiers.[42] Frozen grease had to be removed from every loaded shell[42] and vehicles had to be heated for hours before use.

The Axis offensive on Moscow stopped. As Guderian wrote in his journal, "the offensive on Moscow failed…. We underestimated the enemy's strength, as well as his size and climate. Fortunately, I stopped my troops on December 5, otherwise the catastrophe would be unavoidable."[43]

Soviet Counteroffensive

Although the Wehrmacht's offensive had been stopped, German intelligence estimated that Soviet forces had no more reserves left and thus would be unable to stage a counteroffensive. This estimate proved wrong, as Stalin transferred fresh divisions from Siberia and Far East, relying on intelligence from his spy, Richard Sorge, which indicated that Japan would not attack the Soviet Union. The Red Army had accumulated a 58-division reserve by early December,[42] when the offensive proposed by Zhukov and Vasilevsky was finally approved by Stalin.[44] However, even with these new reserves, Soviet forces committed to the operation numbered only 1,100,000 men,[41] only slightly outnumbering the Wehrmacht. Nevertheless, with careful troop deployment, a ratio of two-to-one was reached at some critical points.[42] On December 5, 1941, the counteroffensive started on the Kalinin Front. After two days of little progress, Soviet armies retook Krasnaya Polyana and several other cities in the immediate vicinity of Moscow.[2]

The same day, Hitler signed his directive number 39, ordering the Wehrmacht to assume a defensive stance on the whole front. However, German troops were unable to organize a solid defense at their present locations and were forced to pull back to consolidate their lines. Guderian wrote that discussions with Hans Schmidt and Wolfram von Richthofen took place the same day, and both commanders agreed that the current front line could not be held.[45] On December 14, Franz Halder and Günther von Kluge finally gave permission for a limited withdrawal to the west of the Oka river, without Hitler's approval.[46] On December 20, 1941, during a meeting with German senior officers, Hitler cancelled the withdrawal and ordered his soldiers to defend every patch of ground, "digging trenches with howitzer shells if needed."[47] Guderian protested, pointing out that losses from cold were actually greater than combat losses and that winter equipment was held by traffic ties in Poland.[48] Nevertheless, Hitler insisted on defending the existing lines, and Guderian was dismissed by Christmas, along with generals Hoepner and Strauss, commanders of the 4th Panzers and 9th Army, respectively. Fedor von Bock was also dismissed, officially for "medical reasons."[1] Walther von Brauchitsch, Hitler's commander-in-chief, had been removed even earlier, on December 19, 1941.[49]

Meanwhile, the Soviet offensive continued; in the north, Klin and Kalinin were liberated on December 15 and December 16, as the Kalinin Front drove west. The Soviet front commander, General Konev, attempted to envelop Army Group Center, but met strong opposition near Rzhev and was forced to halt, forming a salient that would last until 1943. In the south, the offensive went equally well, with Southwestern Front forces relieving Tula on December 16, 1941. In the center, however, progress was much slower, and Soviet troops liberated Naro-Fominsk only on December 26, Kaluga on December 28, and Maloyaroslavets on January 2, after ten days of violent action.[2] Soviet reserves ran low, and the offensive halted on January 7, 1942, after having pushed the exhausted and freezing German armies back 100 to 250 km (60 to 150 mi) from Moscow. This victory provided an important boost for Soviet morale, with the Wehrmacht suffering its first defeat. Having failed to vanquish the Soviet Union in one quick strike, Germany now had to prepare for a prolonged struggle. The blitzkrieg on Moscow had failed.

Aftermath

The Red Army's winter counteroffensive drove the Wehrmacht from Moscow, but the city was still considered to be threatened, with the front line still relatively close. Thus, the Moscow direction remained a priority for Stalin, who had been frightened by the initial German success. In particular, the initial Soviet advance was unable to level the Rzhev salient, held by several divisions of Army Group Center. Immediately after the Moscow counteroffensive, a series of Soviet attacks (the Battles of Rzhev) were attempted against the salient, each time with heavy losses on both sides. Soviet losses are estimated to be between 500,000 and 1,000,000 men, and German losses between 300,000 and 450,000 men. By early 1943, however, the Wehrmacht had to disengage from the salient as the whole front was moving west. Nevertheless, the Moscow front was not finally secured until October 1943, when Army Group Center was decisively repulsed from the Smolensk landbridge and from the left shore of the upper Dnieper at the end of the Second Battle of Smolensk.

Furious that his army had been unable to take Moscow, Hitler dismissed his commander-in-chief, Walther von Brauchitsch, on December 19, 1941, and took personal charge of the Wehrmacht,[49] effectively taking control of all military decisions and setting most experienced German officers against him. Additionally, Hitler surrounded himself with staff officers with little or no recent combat experience. As Guderian wrote in his memoirs, "This created a cold (chill) in our relations, a cold (chill) that could never be eliminated afterwards."[50] This increased Hitler's distrust of his senior officers and ultimately proved fatal to the Wehrmacht. Germany now faced the prospect of a war of attrition for which it was not prepared. The battle was a stinging defeat for the Axis, though not necessarily a crushing one; however, it did end German hopes for a quick and decisive victory over the Soviet Union.

For the first time since June 1941, Soviet forces had stopped the Germans and driven them back. As a result Stalin became overconfident, deciding to further expand the offensive. On January 5, 1942, during a meeting in the Kremlin, Stalin announced that he was planning a general spring counteroffensive, which would be staged simultaneously near Moscow, Leningrad and in southern Russia. This plan was accepted over Zhukov's objections.[51] However, low Red Army reserves and Wehrmacht tactical skill led to a bloody stalemate near Rhzev, known as the "Rzhev meat grinder," and to a string of Red Army defeats, such as the Second Battle of Kharkov, the failed elimination of the Demyansk pocket, and the encirclement of General Vlasov's army near Leningrad in a failed attempt to lift the siege of the city. Ultimately, these failures would lead to a successful German offensive in the south and to the Battle of Stalingrad.

Nevertheless, the defense of Moscow became a symbol of Soviet resistance against the invading Axis forces. To commemorate the battle, Moscow was awarded the title of "Hero City" in 1965, on the 20th anniversary of Victory Day.[2] The "Defense of Moscow" medal was created in 1944, and was awarded to soldiers, civilians, and partisans who took part in the battle.[52]

Casualties

Both German and Soviet casualties during the battle of Moscow have been a subject of debate, as various sources provide somewhat different estimates. Not all historians agree on what should be considered the "Battle of Moscow" in the timeline of World War II. While the start of the battle is usually regarded as the beginning of Operation Typhoon on September 30, 1941 (or sometimes on October 2, 1941), there are two different dates for the end of the offensive. In particular, some sources (such as Erickson[53] and Glantz[54]) exclude the Rzhev offensive from the scope of the battle, considering it as a distinct operation and making the Moscow offensive "stop" on January 7, 1942–thus lowering the number of casualties. Other historians, who include the Rzhev and Vyazma operations in the scope of the battle (thus making the battle end in May 1942), give higher casualty numbers.[2][1] Since the Rzhev operation started on January 8, 1942, with no pause after the previous counteroffensive, such a stance is understandable.

There are also significant differences in figures from various sources. John Erickson, in his Barbarossa: The Axis and the Allies, gives a figure of 653,924 Soviet casualties between October 1941 and January 1942.[53] Glantz, in his book When Titans Clashed, gives a figure of 658,279 for the defense phase alone, and of 370,955 for the winter counteroffensive until January 7, 1942.[54] The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, published in 1973–1978, estimates 400,000 German casualties by January, 1942.[1] Another estimate available is provided in the Moscow Encyclopedia, published in 1997; its authors, based on various sources, give a figure of 145,000 German and 900,000 Soviet casualties for the defensive phase, along with 103,000 German and 380,000 Soviet casualties for the counteroffensive until January 7, 1942.[2] Therefore, total casualties between September 30, 1941 and January 7, 1942 are estimated to be between 248,000 and 400,000 for the Wehrmacht (GSE / Moscow encyclopedia estimate) and between 650,000 and 1,280,000 for the Red Army (Erickson / Moscow Encyclopedia estimate).

|

Western Europe · Eastern Europe · China · Africa · Mediterranean · Asia and the Pacific · Atlantic | |||||

|

Major participants |

Timeline |

Aspects | |||

|

Principal co-belligerents in italics. |

Prelude 1939 1940 1941 1942 |

1943 1944 1945 • more military engagements Aftermath |

• Attacks on North America Civilian impact and atrocities | ||

| Allies | Axis | ||||

|

at war from 1937 entered 1939 entered 1940 |

entered 1941 entered 1942 entered 1943 entered 1944 • others |

at war from 1937 entered 1939 entered 1940 entered 1941 entered 1942 • others | |||

| Resistance movements Austria · Baltic1 · Czechoslovakia · Denmark · Ethiopia · France · Germany · Greece · Italy · Jewish · Netherlands · Norway · Poland · Thailand · USSR · Ukraine2 · Vietnam · Yugoslavia · others | |||||

|

1 Anti-Soviet. | |||||

| Campaigns & Theatres of |

|---|

| Europe Poland – Phoney War – Finland – Denmark & Norway – France & Benelux – Britain – Eastern Front – North West Europe (1944–45) The Mediterranean, Africa and The Middle East Mediterranean Sea – East Africa – North Africa – West Africa – Balkans (1939–41) – Middle East – Yugoslavia – Madagascar – Italy Asia & The Pacific |

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Great Soviet Encyclopedia (Moscow: 1973–1978), entry "Battle of Moscow 1941–42"

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 Moscow Encyclopedia. ed. Great Russian Encyclopedia. (Moscow: 1997), entry "Battle of Moscow"

- ↑ Heinz Guderian. Erinnerungen eines Soldaten (Memoirs of a soldier). (Smolensk: Rusich, 1999), 229.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Great Soviet Encyclopedia entry "Battle of Smolensk" (Moscow: 1973–1978)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Guderian, 272.

- ↑ Guderian, 267–269.

- ↑ A.M. Vasilevsky. The matter of my whole life. (Moscow: Poitizdat, 1978), 134.

- ↑ Marshal G.K. Zhukov. Memoirs. (Moscow: Olma-Press, 2002), 352.

- ↑ Zhukov, 353.

- ↑ Vasilevsky, 135.

- ↑ Guderian, 305.

- ↑ Adolf Hitler, in "Völkischer Beobachter" (Racial Observer), October 10, 1941.(a Nazi newspaper)

- ↑ Guderian, 307–309.

- ↑ Guderian, 307

- ↑ Vasilevsky, 139.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 David M. Glantz, and Jonathan M. House. When Titans clashed: how the Red Army stopped Hitler. (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1995), chapter 6, sub-ch. "Viaz'ma and Briansk," 74 ff.

- ↑ Vasilevsky, 138.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Vasilevsky, 139.

- ↑ Guderian, 316.

- ↑ Richard Overy. Russia's War. (London: Penguin, 1997), 113–114): "Both sides now struggled in the autumn mud. On October 6 [1941] the first snow had fallen, unusually early. It soon melted, turning the whole landscape into its habitual trackless state – the rasputitsa, literally the ‘time without roads’. … It is commonplace to attribute the German failure to take Moscow to the sudden change in the weather. While it is certainly true that German progress slowed, it had already been slowing because of the fanatical resistance of Soviet forces and the problem of moving supplies over the long distances through occupied territory. The mud slowed the Soviet build-up also, and hampered the rapid deployment of men and machines."

- ↑ Guderian, 318.

- ↑ Geoffrey Jukes. The Second World War—The Eastern Front 1941–1945. (Osprey, 2002, ISBN 1841763918), 29.

- ↑ Jukes, 31.

- ↑ Zhukov, tome 2, 10.

- ↑ Jukes, 32.

- ↑ Zhukov, tome 2, 17.

- ↑ Zhukov, tome 2, 18.

- ↑ Zhukov, tome 2, 22.

- ↑ Zhukov, tome 2, 24.

- ↑ Guderian, 329–330.

- ↑ Zhukov, tome 2, 23–25.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 32.7 Glantz, When Titans Clashed, chapter 6, sub-ch. "To the Gates," 80ff.

- ↑ Zhukov, tome 2, 27.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Zhukov, tome 2, 28.

- ↑ Zhukov, tome 2, 30.

- ↑ Guderian, 345.

- ↑ Guderian, 340.

- ↑ Pavel Alekseevich Belov. Moscow is behind us. (Moscow, Voenizdat, 1963), 97.

- ↑ Belov, 106.

- ↑ Zhukov, tome 2, 32.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Glantz, ch.6, subchapter "December counteroffensive," 86ff.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 Jukes, 32.

- ↑ Guderian, 354–355.

- ↑ Zhukov, tome 2, 37.

- ↑ Guderian, 353–355.

- ↑ Guderian, 354.

- ↑ Guderian, 360–361.

- ↑ Guderian, 363–364.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Guderian, 359.

- ↑ Guderian, 365.

- ↑ Zhukov, tome 2, 43–44.

- ↑ "Decision of the Praesidium of Supreme Soviet of the USSR", dated May 1, 1944, compiled in Collection of legislative acts related to State Awards of the USSR. (Moscow: ed. Izvestia, 1984).

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 John Erickson and David Dilks. Barbarossa: The Axis and the Allies. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1994), table 12.4

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Glantz, Table B

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Braithwaite, Rodric. Moscow 1941: A City and Its People at War. London: Profile Books Ltd, 2006. ISBN 186197759X

- Collection of legislative acts related to State Awards of the USSR. Moscow: ed. Izvestia, 1984.

- Belov, Pavel Alekseevich. Za nami Moskva. (Moscow is behind us). Moscow: Voenizdat, 1963.

- Erickson, John and David Dilks. Barbarossa: The Axis and the Allies. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1994. ISBN 0748605045

- Glantz, David M. and Jonathan M. House. When Titans clashed: how the Red Army stopped Hitler. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1995. ISBN 070060717X

- Guderian, Heinz. Erinnerungen eines Soldaten. Heidelberg: Vowinckel, 1951.

- Guderian, Heinz. Panzer Leader. New York: Da Capo Press, 2001. ISBN 0306811014 (in English)

- Jukes, Geoffrey. The Second World War: The Eastern Front 1941–1945. Oxford: Osprey, 2002. ISBN 1841763918

- Nagorski, Andrew. The Greatest Battle: Stalin, Hitler, and the Desperate Struggle for Moscow That Changed the Course of World War II. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007. ISBN 0743281101

- Overy, Richard. Russia's War. London: Penguin, 1997. ISBN 1575000512

- Prokhorov, A. M., ed. Great Soviet Encyclopedia. New York: Macmillan, 1973–1978.

- Reinhardt, Klaus. Moscow: The Turning Point? The Failure of Hitler's Strategy in the Winter of 1941–42. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 1992. ISBN 0854966951

- Sokolovskii, Vasilii Danilovich. Razgrom Nemetsko-Fashistskikh Voisk pod Moskvoi (with map album). Moscow: VoenIzdat, 1964. LCCN: 65-54443.

- Vasilevsky, A. M. Lifelong cause. Moscow: Progress, 1981. ISBN 0714718300

- Zhukov, G. K. The memoirs of Marshal Zhukov. London: Cape, 1971. ISBN 0224619241

External links

All links retrieved September 22, 2023.

- Moscow Attacked!—Free/educational Battle of Moscow boardgame.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.