Difference between revisions of "Yahweh" - New World Encyclopedia

Scott Dunbar (talk | contribs) m (Minor edit) |

m ({{Paid}}) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}} {{Contracted}} | + | {{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}} {{Contracted}} |

[[Image:Tetragrammaton.png|thumb|250px|The four-letter "Tetragrammaton" ''YHWH'' in Phoenician, Aramaic, and Modern Hebrew scripts.]] | [[Image:Tetragrammaton.png|thumb|250px|The four-letter "Tetragrammaton" ''YHWH'' in Phoenician, Aramaic, and Modern Hebrew scripts.]] | ||

Revision as of 21:37, 29 August 2006

Yahweh (יְהוָֹה) (ya·'we), is the primary Hebrew name of God in the Bible. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—though using different names for him—all affirm that Yahweh is God. Jews normally do not pronounce this name, considering it too holy to verbalize. Instead they refer either to Adonai, Elohim, or Hashem (see below). In Christian Bibles, Yahweh is usually translated as "the Lord," a rough equivalent to the Hebrew "Adonai." Muslims refer to God as "Allah," which originates from the same etymological root as "Elohim."

"Jehovah" (also spelled Yahovah) is a modern mispronunciation of the Hebrew word, YHWH, (formerly transcribed "JHVH") inserting the vowels from the word Adonai.

While the original concept of Yahweh may not have been monotheistic, the Hebrew prophets insisted that the people of Israel must worship him alone. Yahweh-centered monotheism eventually became the normative Jewish religion, and this in turn was inherited by both Christianity and Islam. Yahwist monotheism has also come to influence other religions through the centuries, both as the result of missionary activity and interreligious dialogue.

The historical contribution of Yahwism is a mixed one. Monotheistic belief forms the core of three great Abrahamic faiths and is said to be incompatible with idolatry, priestly corruption, and superstition. On the other hand, Yahwism and its monotheistic offspring have also been used to justify repression of rival religions, male chauvinism, the persecution and murder of "pagans," terrorism, and even genocide.

Origins

Biblical Tradition

The Bible presents several stories regarding the revelation of God's true name, Yahweh. The best known is the story of Moses and the burning bush of Exodus 3. God makes it clear that Moses is the first to know the secret of the divine name:

- God also said to Moses, "I am the Lord. I appeared to Abraham, to Isaac and to Jacob as God Almighty, but by my name the Lord I did not make myself known to them. (Ex. 6:2-3)

In this sentence three names of God are used: Elohim (God), YHWH (the Lord), and El Shaddai (God Almighty). El Shaddai appears more than 30 times in the Hebrew Bible (Gen. 28:3; 35:11, etc.). Elohim, a plural form of El, (Gen. 1:1, etc.) is used many hundreds of times. YHWH is used more than any other name for God in the Bible, nearly 7,000 times. In most editions, whenever the words "The Lord" are used, ancient Hebrew manuscripts have a form of YHWH.

A problem for Biblical scholars is the fact that the Book of Genesis appears to contradict the story in Exodus regarding the first time that humans came to known God's true name. While Exodus states clearly that Moses was the first to know God's true name, Gen 2:19 says that men first called on "the name of YHWH" in the days of Seth, the third son of Adam and Eve. Gen. 12:8 specifies that at Bethel (the "place of El"), Abraham called on the name of the Lord some 400 years before Moses. The first woman mentioned as calling on the name YHWH is Abraham's wife Sarah. (Gen. 16:13)

The Catholic scholar A.J. Maas suggested one way of resolving the seeming contradiction between Exodus and Genesis regarding the revelation of Yahweh's name: that people knew at least a syllable of God's true name, and began calling themselves after it, long before the whole name was revealed to Moses:

- Among the 163 proper [Biblical] names which bear an element of the sacred name in their composition, 48 have yeho or yo at the beginning, and 115 have yahu or yah and the end, while the form Jahveh [Yahweh] never occurs in any such composition. Perhaps it might be assumed that these shortened forms yeho, yo, yahu, yah, represent the Divine name as it existed among the Israelites before the full name Jahveh was revealed on Mt. Horeb. [1]

A Desert Deity?

A more fundamental question is whether the name Yahweh originated among the Israelites or was adopted by them from some other people and language. The Bible admits that other peoples knew God, but not by the name Yahweh. For example, in the story of Abraham we met the mysterious priest-king of Salem (the future Jerusalem), Melchizedek by name, who shares a sacramental meal with the patriarch:

- Then Melchizedek king of Salem brought out bread and wine. He was priest of God Most High, and he blessed Abram, saying, "Blessed be Abram by God Most High, Creator of heaven and earth. And blessed be God Most High, who delivered your enemies into your hand." Then Abram gave him a tenth of everything. (Gen. 14: 18-20)

The deity to whom Abraham offers his tithe after sharing this sacred meal with Melchizedek is literally Elyon El — or El Elyon, the "highest god." Thus the residents of Salem, as well as other people of the region, seem to know God. However, with regard to God as Yahweh, the Bible apparently reserves knowledge of the name to the chosen people. Even if people began to call Yahweh's name in the time of Seth, only the patriarchs themselves are specifically mentioned as calling him by that name. The implication is that outside of the Israelites, no other people knew of Yahweh by his true name.

Modern scholarship, however, takes a different view. For example, Biblical archaeologist Amihai Mazar, in Archaeology of the Land of the Bible, finds that the association of Yahweh with the desert may be the product of his origins in the dry lands to the south of Israel. A specific suggestion, provided by Biblical scholar Mark S. Smith in The Origins of Biblical Monotheism, is that Yahweh originated with a group known as the Shasu, Canaanite nomads from southern transjordan. An Egyptian inscription at Karnak from the time of Pharaoh Amenhotep III (1390-1352 B.C.E.) refers to the "Shasu of Yhw," evidence that this god was worshiped among some of the Shasu tribes at this time. Egyptologist Donald Redford, in Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times, suggests that the Israelites may have been a group of Shasu who migrated northward into Canaan in the 13th century b.c.e.. Archaeologist Israel Finkelstein has shown in The Bible Unearthed that some of the Shasu indeed settled in the Samarian and Judean hills at this time, thus forming one of the proto-Israelite peoples.

One Biblically-derived theory somewhat consistent with the above scenario holds that Yahweh was originally a deity of the Midianites and other desert tribes. The Exodus story tells us that the Israelites had not been worshipers of Yahweh — at least by that name — before the time of Moses. The revelation of the name to Moses was made at Sinai/Horeb, a mountain sacred to Yahweh, south of Canaan in a region where the forefathers of the Israelites were never reported to have roamed. Long after the Israelite settlement in Canaan this region continued to be regarded as the abode of Yahweh (Judges 5:4; Deut. 33:2; I Kings 19:8, etc). Moses is closely connected with the tribes in the vicinity of this holy mountain.

According to one account, Moses' wife was a daughter of Jethro, a priest of Midian (Ex. 18). When Moses led the Israelites to the mountain after their deliverance from Egypt, Jethro came to meet him, extolling Yahweh as greater than all other gods. The Midianite priest "brought a burnt offering and other sacrifices to God," and the chief men of the Israelites were guests at his sacrificial feast. It can be interpreted that because Jethro was a Midianite priest who offered sacrifices to Yahweh, the tribes in the region of Sinai/Horeb may already have been worshipers of Yahweh — although not exclusively — before the time of Moses.

Another theory is that Yahweh (or Yahu, Yaho) is the name of a god worshiped throughout a great part of the area occupied by the Western Semites. Adherents of this theory point to the occurrence in various parts of this territory of non-Jewish proper names incorporating these syllables.

The tradition of Genesis, according to which the forefathers had worshiped Yahweh from time immemorial, may indicate that Judah and its kindred clans had in fact been worshipers of Yahweh before the time of Moses.

Many attempts have been made to trace the West Semitic Yah back to Babylonia. Thus the early 20th century Assyriologist Friedrich Delitzsch believed the name derived from an Akkadian god, Ia. A relation between Yahweh with [Ea, also called Enki, one of the great Babylonian gods, has also been mentioned occasionally. However, scholars are now generally agreed that, so far as Yahu or Yah occurs in Babylonian texts, it is as the name of a foreign West Semitic deity.

Finally we should mention the theory first propounded by Sigmund Freud that Moses brought the One God idea with him from Egypt, having learned it from the Egyptian King Akenaten, who attempted to make Egypt into a monotheistic society centering on the sun god.

Meaning

- Moses said to God, "Suppose I go to the Israelites and say to them, 'The God of your fathers has sent me to you,' and they ask me, 'What is his name?' Then what shall I tell them?" God said to Moses, "I am who I am. This is what you are to say to the Israelites: 'I AM has sent me to you.' " (Ex. 3:13-14)

The symbolic or spiritual meaning of God's name is the subject of debate in several religious traditions. In one of these, Yahweh is related to the Hebrew verb הוה (ha·wah, "to be, to become"), meaning "He will cause to become." In Arabic Yahyâ means "He [who] lives".

A related Jewish tradition regards the name as coming from three different verb forms sharing the same root — YWH. The three words are: HYH (היה —haya, He was"); HWH (הוה — howê,"He is"); and YHYH (יהיה — yihiyê, "He will be"). This is believed to show that God is timeless. This formula has also been used by Christians to demonstrate the supposed trinitarian basis of God's existence.

Another interpretation is that the name means "I am the One Who Is." This can be seen in the traditional account of God commanding Moses to tell the sons of Israel that "I AM (אהיה) has sent you." (Exodus 3:13-14)

Some also suggest: "I AM the One I AM" (אהיה אשר אהיה), or "I AM what I need to become". This may also fit the interpretation of "He Causes to Become." Other scholars believe that the most proper meaning may be "He Brings Into Existence Whatever Exists" or "He who causes to exist".

Yahweh's Characteristics

In its mature form, the concept of Yahweh represents the Jewish God as the absolute, eternal, unchanging Creator of the universe who is also a personal being who cares intensely for mankind as a father does for his child or a husband does for his wife. Among his divine attributes are mercy, wisdom, righteousness, lovingkindness, justice, compassion, patience, and beauty. However he is also a jealous deity. Although he is slow to anger, he will harshly punish those who betray him, including the whole people of Israel, in order to bring about their eventual repentance and reconciliation. The classical expression of this theology is found in Exodus 34, in the scene in which God appears to Moses just after Moses ascends Sinai to received the Ten Commandments a second time:

- Then the Lord came down in the cloud and stood there with him and proclaimed his name, the Lord [YHWH]. And he passed in front of Moses, proclaiming, "YHWH, YHWH, the compassionate and gracious God, slow to anger, abounding in love and faithfulness, maintaining love to thousands, and forgiving wickedness, rebellion and sin. Yet he does not leave the guilty unpunished; he punishes the children and their children for the sin of the fathers to the third and fourth generation." (Ex. 34:6-7)

Sections of the Bible thought to be among the earliest, however, also portray Yahweh in a more primitive way. One such example is Psalm 18, in which Yahweh, far from being a transcendent being abounding in love, could easily be confused with a pagan storm deity or warrior god:

- The earth trembled and quaked, and the foundations of the mountains shook; they trembled because he was angry. Smoke rose from his nostrils; consuming fire came from his mouth, burning coals blazed out of it. He parted the heavens and came down; dark clouds were under his feet. He mounted the cherubim and flew; he soared on the wings of the wind. He made darkness his covering, his canopy around him — the dark rain clouds of the sky. Out of the brightness of his presence clouds advanced, with hailstones and bolts of lightning. YHWH thundered from heaven; the voice of the Most High resounded. He shot his arrows and scattered the enemies, [sent] great bolts of lightning and routed them. (Psalm 18:7-14)

The association of Yahweh with storm and fire is frequent in the Old Testament. The thunder is the voice of Yahweh, the lightning his arrows, the rainbow his bow. The revelation at Sinai is amid the awe-inspiring phenomena of tempests. Scholars have also noted that many of these primitive characteristics of Yahweh are seen in hymns and inscriptions devoted to Baal of the Canaanites and Marduk of Mesopotamia.

Relationship to Other Deities

In the "Song of Moses," the great prophet asks:

- "Who among the gods is like you, O Lord? Who is like you — majestic in holiness, awesome in glory, working wonders?" (Ex. 15:11)

A great deal of discussion has been devoted to the relationship of Yahweh to the other deities of the region. We have already mentioned the fact that the Hebrews worshiped their God as El Shaddai, El Elyon, Elohim, etc. Outside the Bible, El is known as the chief deity of the Canaanite religion. He was the father of the Canaanite god Baal and the husband of the mother goddess Ashera. Interestingly, the word "Baal" also means "lord" or "master." An indication that Baal and Yahweh were sometimes identified is evidenced in the words of the prophet Hosea, who says: "In that day," declares the Lord, [YHWH] "you will call me 'my husband'; you will no longer call me 'my master [baal].'" (Hosea 2:16))

In fact archaeologists and language experts indicate that it is difficult to distinguish Israelite and Canaanite culture until the early Early Iron Age, around the time of King David. We can imagine a situation in which some of the proto-Israelites worshiped a variety of gods, or worshiped God in a variety of forms using many names. Thus, Jeru-baal (Gideon) — was named for both Yahweh and Baal; while the Judge Shamgar ben Anath was named after the war goddess Anat. King Saul, anointed by the Yahwist prophet Samuel as Israel's first king, nevertheless named his sons Ish-baal and Meri-baal. Many modern scholars believe that eventually, some of the characteristics of Yahweh, El, and Baal merged into Yahweh/Elohim. Baal, on the other hand, was denigrated and excluded, just as the bronze serpent icon associated with Moses (Num. 21: 9) was eventually destroyed as an idol (2 Kings 18:4). So too was the goddess Ashera disowned, while the chief deities of other ethnic groups were treated as having nothing in common with Yahweh.

The issue is complicated by the question of whether the Israelites were truly one distinct people descended from Abraham who migrated en masse from Egypt to Canaan, rather than a confederation of previously unrelated people who came to accept a common national identity, religious mythology, and origin story. In any case, there is much evidence that the Yahweh-only ideology did not come to the fore among the Israelites until well into the period of Kings, and it was not until after the Babylonian exile that monotheism took firm root among the Jews.

Yahweh himself was sometimes worshiped in a way that later generations would consider idolatrous. For example, presence of golden cherubim and cast bronze bull statues at the Temple of Jerusalem leads many scholars to question whether the Second Commandment against graven images could have been in effect at this time, rather than being the creation of a later age written back into history by the biblical authors. Describing an earlier period, Judges 17-18 tells the story of a wealthy Ephraimite woman who consecrates 1100 pieces of silver to Yahweh to be cast into an image and put into the family shrine along with other idols. Her son then hires a Levite who serves as priest at the family's altar, successfully inquiring there of Yahweh on behalf of passing travelers from the tribe of Dan. The Danites later steal the idols and take them along with the priest to settle in the north. A grandson of Moses named Jonathan becomes their chief priest.

The tale serves as a precursor the later story of the northern king Jeroboam I erecting idolatrous bull-calf altars at Dan and Bethel in competition with the Temple of Jerusalem. English translations portray Jeroboam as saying "Here are your gods, O Israel" at the unveiling. The Hebrew, however, is "here is elohim," the same word normally translated at "God." Bull calves were associated with the worship of El, and bulls were routinely offered to Yahweh on horned altars. Here we see the process by which certain aspects of El worship — such as horned altars and the sacrifice of cattle — were accepted into the worship of Yahweh, while others — such as the veneration of the bull-calf icon and the recognition of Baal as one of El's sons — were disowned.

William Dever discusses another intriguing question in his book Did God Have a Wife? He presents archaeological evidence suggesting that the goddess Ashera was seen as Yahweh's consort in certain times and places. An echo of language associated with Ashera worship may be found in Genesis 49:25, which sates: "The Almighty (Shaddai)... blesses you with blessings... of the breast and womb." The Bible is clear that the Queen of Heaven was worshiped by families who also honored Yahweh in Jeremiah's day. (Je. 7:17–18) Dever suggests that Ashera worship remained widespread among the common folk, while the elites, centering on the male priesthood, fought to exclude any feminine portrayals of God. Eventually, many of the characteristics of Ashera were included in the rabbinic concept of the Shekhina.

The Bible seems to indicate that even though the Israelites were forbidden to worship other deities, Yahweh was not considered as the only god who actually existed. The prophet Micah declared: "All the nations may walk in the name of their gods; we will walk in the name of the Lord our God for ever and ever." (Micah 4:5) Yahweh is often referred to in the Bible as "the god of the hebrews" (there being no capitalization in the Hebrew text), thus portrayed as one of several tribal deities rather than as the only God in existence.

Psalm 82, on the other hand, seems to mark a transition point, in which God will no longer accept coexistence with other deities:

- God [elohim] standeth in the congregation of God [or the gods: "elohim"]; He judgeth among the gods [elohim]... They know not, neither do they understand; They walk to and fro in darkness: All the foundations of the earth are shaken. I said, Ye are gods, And all of you sons of the Most High. Nevertheless ye shall die like men, And fall like one of the princes. (Psalm 82:1-7 — ASV)

The portrait of God acting as judge in the assembly of the gods has obvious parallels in other religious traditions: El is the chief of the divine assembly in Canaanite religion, just as Zeus is the head of the court at Olympus. Here, however, God has pronounced a sentence of capital punishment on the other gods. This parallels the viewpoint of Jeremiah 10.11: "The gods who did not make the heavens and the earth shall perish from the earth and from under the heavens." (RSV) In this way the concept of Yahweh as the chief god begins to shift into that of Yahweh/Elohim as the only true deity, with other gods in the position of either demons or creatures of man's imagination.

The Tetragrammaton

The four consonants of the Hebrew spelling of Yahweh are referred to as the Tetragrammaton (Greek: τετραγράμματον; "word with four letters"). It is spelled in the Hebrew alphabet: yodh, heh, vav, heh — YHWH. Of all the names of God, the one which occurs most frequently in the Hebrew Bible is the Tetragrammaton, appearing 6,823 times, according to the on-line Jewish Encyclopedia.

In Judaism, pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton is a taboo Usually, Adonai ("the Lord") is used as a substitute in prayers or readings from the Torah. When used in everyday speaking the Tetragrammaton is often replaced by HaShem ("the Name").

According to rabbinic tradition, the name was pronounced by the high priest on Yom Kippur, the only day when the Holy of Holies of the Temple would be entered. With the destruction of the Second Temple in the year 70 C.E., this use also vanished, explaining the loss of the correct pronunciation.

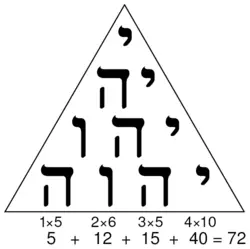

Beginning in the middle ages, the Tetragrammaton was widely contemplated as a tool used in mystical enlightenment, especially in kabbalistic literature, as well is in magical incantations and spells. In one mystical tradition, each letter of the 4-letter form of the Name represents a metaphoric symbol of the living power of God. Also, when the letters of the Tetragrammaton are arranged in a kabbalistic tetractys formation, the sum of all the letters is 72 by Gematria — a rabbinic system of assigning a numerical value to each letter of the alphabet — as shown in the diagram.

In another tradition, the mystical sacred name is actually 72 letters long and the high priest is said to have communed with the Almighty using this 72-letter name of God, which was written out on a long strip of parchment, folded and slipped inside the high priest's bejeweled breastplate. When someone would ask the high priest a question of Jewish law, the high priest could invoke the name, wherein according to lore the 12 jewels on the breastplate, representing the 12 tribes of the Israelites, would light up with the glory of God.

The number 72 has a number of significances [2] both scientifically and mystically. Besides being the product of 6 times 12 (the number of points on the Star of David times the number of the tribes of Israel), it is also the sum of four successive prime numbers (13 + 17 + 19 + 23), as well as the sum of six consecutive primes (5 + 7 + 11 + 13 + 17 + 19). It is also a "prone number," meaning the product of two successive integers (8 and 9).

The number 72 is also:

- The average number of heartbeats per minute for a resting adult.

- The conventional number of scholars translating the ancient Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible, used as a basis for most English versions of the scriptures.

- The number of disciples sent forth by Jesus in Luke 10 in some manuscripts (seventy in others).

- The total number of books in the Holy Bible in the Catholic version if the Book of Lamentations is considered part of the Book of Jeremiah.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Armstrong, Karen, A History of God, Alfred A. Knopf, 1993.

- Dever, William G., Did God Have A Wife? Archaeology And Folk Religion In Ancient Israel, William. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2005.

- Dever, William G., Who Were the Early Israelites? William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids, MI, 2003.

- Finkelstein, Israel, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts, New York: Free Press, 2002.

- Hadley, Judith M., The Cult of Asherah in Ancient Israel and Judaism, University of Cambridge 2000.

- Redford, Donald B., Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times, Princeton University Press, Reprint edition, 1993.

- Smith, Mark S., The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2002.

- Smith, Mark S., The Origins of Biblical Monotheism:Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts, Oxford University Press, paperback edition, 2003

- Patai, Raphael, The Hebrew Goddess, Wayne State University Press, 1990.

External links

- "The Names of God" in The Jewish Encyclopedia

- "Yahweh" in Encyclopedia Mythica. 2004.

- "Jehovah" in Easton's Bible Dictionary (3rd ed.) 1887.

- "Jehovah (Yahweh)" in the Catholic Encyclopedia

- The Historical Evolution of the Hebrew God

- The Rise of God

- The Sacred Name Yahweh

- Biblaridion magazine: Phanerosis Theology: The Tetragrammaton and God's manifestation.

- YHWH/YHVH — Tetragrammaton

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.