Difference between revisions of "Silk" - New World Encyclopedia

(notes revised) |

(article ready, image(s) currently in article are ok to use) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{ready}}{{images OK}} | ||

| + | |||

[[Image:Silk Dresses by David Shankbone.jpg|thumb|Silk dresses]] | [[Image:Silk Dresses by David Shankbone.jpg|thumb|Silk dresses]] | ||

'''Silk''' is a natural [[protein]] [[fiber]], some forms of which can be [[weaving|woven]] into [[textile]]s. The best-known type of silk is obtained from [[Pupa#Cocoon|cocoon]]s made by the [[larva]]e of the [[silkworm]] ''[[Bombyx mori]]'' reared in captivity ([[sericulture]]). The shimmering appearance for which silk is prized comes from the fibers' triangular [[prism (optics)|prism]]-like structure which allows silk cloth to refract incoming light at different angles. | '''Silk''' is a natural [[protein]] [[fiber]], some forms of which can be [[weaving|woven]] into [[textile]]s. The best-known type of silk is obtained from [[Pupa#Cocoon|cocoon]]s made by the [[larva]]e of the [[silkworm]] ''[[Bombyx mori]]'' reared in captivity ([[sericulture]]). The shimmering appearance for which silk is prized comes from the fibers' triangular [[prism (optics)|prism]]-like structure which allows silk cloth to refract incoming light at different angles. | ||

| Line 194: | Line 196: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * | + | * [http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb3284/is_199512/ai_n7993879 On the question of silk in pre-Han Eurasia] - Retrieved November 15, 2007. |

| − | * | + | * [http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/weilue/weilue.html The Peoples of the West from the Weilue] - Retrieved November 15, 2007. |

| − | * | + | * [http://www.uni-tuebingen.de/uni/ans/eastm/back/cs12/cs12-4-kuhn.pdf Silk Weaving in Ancient China: From Geometric Figures to Patterns of Pictorial Likeness] - Retrieved November 15, 2007. |

| − | * | + | * Lui, Hsin-ju. 1996. ''Silk and religion an exploration of material life and the thought of people, AD 600-1200''. Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195636554 |

* Sung, Ying-Hsing. 1637. ''Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century - T'ien-kung K'ai-wu''. Translated and annotated by E-tu Zen Sun and Shiou-chuan Sun. Pennsylvania State University Press, 1966. Reprint: Dover, 1997. Chap. 2. Clothing materials. | * Sung, Ying-Hsing. 1637. ''Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century - T'ien-kung K'ai-wu''. Translated and annotated by E-tu Zen Sun and Shiou-chuan Sun. Pennsylvania State University Press, 1966. Reprint: Dover, 1997. Chap. 2. Clothing materials. | ||

| − | * Kadolph, Sara J. Textiles | + | * Kadolph, Sara J. 2007. ''Textiles''. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0131187694 P.76-81. |

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| + | All links retrieved November 15, 2007. | ||

{{Commonscat|Silk}} | {{Commonscat|Silk}} | ||

*[http://silkwormmori.blogspot.com/2007/10/research-updates.html THE SILKWORM]A germline transgenic silkworm that secretes recombinant proteins in the sericin layer of cocoon | *[http://silkwormmori.blogspot.com/2007/10/research-updates.html THE SILKWORM]A germline transgenic silkworm that secretes recombinant proteins in the sericin layer of cocoon | ||

| − | |||

*[http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/secondary/SMIGRA*/Sericum.html References to silk by Roman and Byzantine writers] | *[http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/secondary/SMIGRA*/Sericum.html References to silk by Roman and Byzantine writers] | ||

*[http://www.geospace.co.uk/silk/worldsilk.html A series of maps depicting the global trade in silk] | *[http://www.geospace.co.uk/silk/worldsilk.html A series of maps depicting the global trade in silk] | ||

Revision as of 21:11, 15 November 2007

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The best-known type of silk is obtained from cocoons made by the larvae of the silkworm Bombyx mori reared in captivity (sericulture). The shimmering appearance for which silk is prized comes from the fibers' triangular prism-like structure which allows silk cloth to refract incoming light at different angles.

"Wild silks" are produced by caterpillars other than the mulberry silkworm (Bombyx mori). They are called "wild" as the silkworms cannot be artificially cultivated like Bombyx mori. A variety of wild silks have been known and used in China, India, and Europe from early times, although the scale of production has always been far smaller than that of cultivated silks. Aside from differences in colors and textures, they all differ in one major aspect from the domesticated varieties: the cocoons that are gathered in the wild have usually already been damaged by the emerging moth before the cocoons are gathered, and thus the single thread that makes up the cocoon has been torn into shorter lengths. Commercially reared silkworm pupae are killed before the adult moths emerge by dipping them in boiling water or piercing them with a needle, thus allowing the whole cocoon to be unraveled as one continuous thread. This allows a much stronger cloth to be woven from the silk. Wild silks also tend to be more difficult to dye than silk from the cultivated silkworm.

There is some evidence that small quantities of wild silk were already being produced in the Mediterranean area and the Middle East by the time the superior, and stronger, cultivated silk from China began to be imported (Hill 2003, Appendix C).

Silks are produced by several other insects, but only the silk of moth caterpillars has been used for textile manufacture. There has been some research into other silks, which have differences at the molecular level. Silks are mainly produced by the larvae of insects with complete metamorphosis, but also by some adult insects such as webspinners. Silk production is especially common in the Hymenoptera (bees, wasps, and ants), and is sometimes used in nest construction. Other types of arthropod produce silk, most notably various arachnids such as spiders (see spider silk).

History of silk

China

Silk fabric was first developed in ancient China, possibly as early as 6000 B.C.E. and definitely by 3000 B.C.E. Legend gives credit to a Chinese empress, Xi Ling-Shi (Hsi-Ling-Shih, Lei-Tus). Silks were originally reserved for the kings of China for their own use and gifts to others, but spread gradually through Chinese culture both geographically and socially, and then to many regions of Asia. Silk rapidly became a popular luxury fabric in the many areas accessible to Chinese merchants because of its texture and luster. Silk was in great demand, and became a staple of pre-industrial international trade. In July of 2007, archeologists have discovered intricately weaved and dyed silk textiles in a tomb of Jiangxi province that are dated to the Eastern Zhou Dynasty, roughly 2,500 years ago.[1] Although historians have suspected a long history of a formative textile industry in ancient China, this find of silk textiles employing "complicated techniques" of weaving and dyeing provides direct and concrete evidence for silks dating before the Mawangdui-discovery and other silks dating to the Han Dynasty (202 B.C.E.–220 C.E.).[1]

The first evidence of the silk trade is the finding of silk in the hair of an Egyptian mummy of the 21st dynasty, c.1070 B.C.E. [1]. Ultimately the silk trade reached as far as the Indian subcontinent, the Middle East, Europe, and North Africa. This trade was so extensive that the major set of trade routes between Europe and Asia has become known as the Silk Road.

The Emperors of China strove to keep knowledge of sericulture secret to maintain the Chinese monopoly. Nonetheless sericulture reached Korea around 200 B.C.E., about the first half of the 1st century AD had reached ancient Khotan[2], and by AD 300 the practice had been established in India.

Thailand

Silk is produced in Thailand's favorable climate by two types of silkworms, the cultured Bombycidae and wild Saturniidae, all the year round, mostly after the rice harvest by villagers from the central and northeast parts of the country. Women traditionally weave silk on hand looms, and pass the skill on to their daughters as weaving is considered to be a sign of maturity and eligibility for marriage. Thai silk textiles often use complicated patterns in various colors and styles. Most regions of Thailand have their own typical silks,

India and Nepal

Silk, known as Pattu or Reshmi in southern parts of India and Resham in Hindi, has a long history in India and is widely produced today. Historically silk was used by the upper classes, while cotton was used by the poorer classes. Today silk is mainly used in Bhoodhan Pochampally (also known as Silk City), Kanchipuram, Dharmavaram, Mysore, etc. in South India and Banaras in the North for manufacturing garments and Sarees. "Murshidabad silk," famous from historical times, is mainly produced in Malda and Murshidabad district of West Bengal and woven with hand looms in Birbhum and Murshidabad district. Another place famous for production of silk is Bhagalpur. The silk from Kanchi is particularly well-known for its classic designs and enduring quality. The silk is traditionally hand-woven and hand-dyed and usually also has silver threads woven into the cloth. Most of this silk is used to make saris. The saris usually are very expensive and vibrant in color. Garments made from silk form an integral part of Indian weddings and other celebrations. In the northeastern state of Assam, three different types of silk are produced, collectively called Assam silk: Muga, Eri and Pat silk. Muga, the golden silk, and Eri are produced by silkworms that are native only to Assam. The heritage of silk rearing and weaving is very old and continues today especially with the production of Muga and Pat riha and mekhela chador, the three-piece silk saris woven with traditional motifs. Mysore Silk Sarees, which are known for their soft texture and expensive class last easily as long as 25 to 30 years, if maintained well.

Mediterranean world

In the Odyssey, 19.233, it is mentioned that Odysseus wore a shirt "gleaming like the skin of a dried onion" (varies with translations, literal translation here[3]). Some researchers proposed that the shirt was made of silk. The Roman Empire knew of and traded in silk. During the reign of emperor Tiberius, sumptuary laws were passed that forbade men from wearing silk garments, but these proved ineffectual.[4] Despite the popularity of silk, the secret of silk-making was only to reach Europe around AD 550, via the Byzantine Empire. Legend has it that monks working for the emperor Justinian I smuggled silkworm eggs to Constantinople in hollow canes. The Byzantines were as secretive as the Chinese, and for many centuries the weaving and trading of silk fabric was a strict imperial monopoly[citation needed]; all top-quality looms and weavers were located inside the Palace complex in Constantinople and the cloth produced was used in imperial robes or in diplomacy, as gifts to foreign dignitaries. The remainder was sold at very high prices.

Islamic world

In Islamic teachings, Muslim men are forbidden to wear silk. Many religious jurists believe the reasoning behind the prohibition lies in avoiding clothing for men that can be considered feminine or extravagant.[5] Despite injunctions against silk for men, silk has retained its popularity in the Islamic world because of its permissibility for women. The Muslim Moors brought silk with them to Spain during their conquest of the Iberian Peninsula.

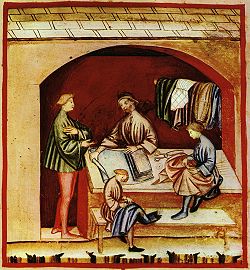

Medieval and modern Europe

Venetian merchants traded extensively in silk and encouraged silk growers to settle in Italy. By the 13th century, Italian silk was a significant source of trade. Since that period, the silk worked in the province of Como has been the most valuable silk in the world. The wealth of Florence was largely built on textiles, both wool and silk, and other cities like Lucca also grew rich on the trade. Italian silk was so popular in Europe that Francis I of France invited Italian silk makers to France to create a French silk industry, especially in Lyon. Mass emigration (especially of Huguenots) during periods of religious dispute had seriously damaged French industry and introduced these various textile industries, including silk, to other countries. James I attempted to establish silk production in England, purchasing and planting 100,000 mulberry trees, some on land adjacent to Hampton Court Palace, but they were of a species unsuited to the silk worms and the attempt failed. Production started elsewhere later. In Italy, the Stazione Bacologica Sperimentale was founded in Padua in 1871 to research sericulture. In the late 19th century, China, Japan, and Italy were the major producers of silk.[citation needed] The most important cities for silk production in Italy were Como and Meldola (Forlì). In medieval times, it was common for silk to be used to make elaborate casings for bananas and other fruits.

Silk was expensive in Medieval Europe and used only by the rich. Italian merchants like Giovanni Arnolfini became hugely wealthy trading it to the Courts of Northern Europe.

North America

James I of England introduced silk-growing to the American colonies around 1619, ostensibly to discourage tobacco planting. Only the Shakers in Kentucky adopted the practice. In the 1800s a new attempt at a silk industry began with European-born workers in Paterson, New Jersey, and the city became a US silk center, although Japanese imports were still more important.

World War II interrupted the silk trade from Japan. Silk prices increased dramatically, and US industry began to look for substitutes, which led to the use of synthetics such as nylon. Synthetic silks have also been made from lyocell, a type of cellulose fiber, and are often difficult to distinguish from real silk (see spider silk for more on synthetic silks).

Mongolia

Mongols used silk as part of the under-armor garments (see Mongolian armor). Silk is tough enough that it was used as very light armor, though its special use was to stop arrow penetration into the body. The silk would stop an arrow from penetrating far enough into the body to be lethal, and the arrow could be pulled out of the wound by tugging on the unbroken silk.[citation needed] The head of an arrow pulled out this way would not contact the body, reducing the likelihood of infection.

Major fiber properties

Physical properties

Shape

Silk has a triangular shaped cross section whose corners are rounded.

Luster

Due to the triangular shape (allowing light to hit it at many different angles), silk is a bright fiber meaning it has a natural shine to it.

Covering power

Silk fibers have poor covering power. This is caused by their thin filament form.

Hand

When held, silk has a smooth, soft texture that, unlike many synthetic fibers, is not slippery.

Denier

4.5 g/d (dry) ; 2.8-4.0 g/d (wet)

Mechanical properties

Strength

Silk is one of the strongest of all the natural fibers; however it does lose up to 20% of its strength when wet.

Elongation/elasticity

Silk has moderate to poor elasticity. If elongated even a small amount the fibers will remain stretched.

Resiliency

Silk has moderate wrinkle resistance

Chemical Properties

Protein Composition

Silk is made up of GLY-SER-GLY-ALA-GLY and forms Beta pleated sheets. Interchain H-bonds are formed while side chains are above and below the plane of the H-bond network. Small residue(Gly) allows tight packing and the fibers are strong and resistant to stretching. The tension is due to covalent peptide bonds. Since the protein forms a Beta sheet, when stretched the force is applied to these strong bonds and they do not break. The 50% GLy composition means that Gly exists regularly at every other position.

Absorbency

Silk has a good moisture regain of 11%.

Electrical conductivity

Silk is a poor conductor of electricity making it comfortable to wear in cool weather. This also means however, that silk is susceptible to static cling.

Resistance to ultraviolet light/biological organisms

Silk can become weakened if exposed to too much sunlight. Silk may also be attacked by insects, especially if left dirty.

Chemical reactivity/resistance

Silk is resistant to mineral acids. It is yellowed by perspiration and will dissolve in sulphuric acid.

Other properties

Dimensional stability

Unwashed silk chiffon may shrink up to 8% due to a relaxation of the fiber macrostructure. So silk should either be prewashed prior to garment construction, or dry cleaned. However, dry cleaning may still shrink the chiffon up to 4%. Occasionally, this shrinkage can be reversed by a gentle steaming with a press cloth. Gradual shrinkage is virtually nonexistent, as is shrinkage due to molecular-level deformation.

Uses for silk

Apparel

Silk is excellent for use in warm weather and active clothing. The silk's good absorbency makes it comfortable to wear in such conditions. Silk is also excellent in the cold because its low conductivity keeps the wearer warm.

Examples of silk clothing

- Shirts

- Blouses

- Formal Dresses

- High Fashion

- Negligees

- Pajamas

- Robes

- Skirtsuits

- Sundresses

- Underwear

Furnishings

Silk's elegant, soft luster and beautiful drape makes it perfect for many furnishing applications.

Examples of silk furnishings

- Upholstery

- Wall Coverings

- Window Treatments (if blended with another fiber)

- Rugs

- Bedding

- Wall Hangings

Animal rights

As the process of harvesting the silk from the cocoon kills the larvae, silk-culture has been criticized in the early 21st century by animal rights activists on the grounds that silk production kills silkworms, and that artificial silks are available.[6] Others point out that silkworms depend upon humans for their survival, and would become extinct without humans to care for the worms and harvest the silk. [7]

Mahatma Gandhi was critical of silk production based on the Ahimsa philosophy. Ahimsa is part of the three millennial Jain philosophy of India "not to hurt any living thing," which led to development of a cotton spinning machine he distributed. Such a machine can be seen in the Gandhi Institute.

Ahimsa Silk, made from the cocoons of wild and semi-wild silk moths, is being promoted in parts of Southern India, for those who prefer not to wear silk produced which involves the death of silkworms.

Other uses

In addition to clothing manufacture and other handicrafts, silk is also used for items like parachutes, bicycle tires, comforter filling and artillery gunpowder bags. Early bulletproof vests were also made from silk in the era of blackpowder weapons until roughly World War I. Silk undergoes a special manufacturing process to make it suitable for use as non-absorbable surgical sutures. Chinese doctors have also used it to make prosthetic arteries. Silk cloth is also used as a material to write on.

Production methods

Sericulture: the production of cultivated silk

- Silk moths lay eggs on specially prepared paper.

- Eggs hatch and the caterpillars are fed fresh mulberry leaves.

- After about 35 days, and 4 moltings, the silkworms are 10,000 times heavier than when hatched – they are now ready to begin spinning a cocoon.

- A straw frame is placed over tray of silkworms – they begin spinning cocoons by moving their heads in a figure 8.

- Liquid silk, coated in sericin, is produced in 2 of the silkworm’s glands, which is forced through spinnerets.

- Sericin: water-soluble protective gum

- Spinnerets: openings in silkworm’s head

- As this liquid silk comes into contact with the air, it solidifies.

- Within 2-3 days, the silkworm will have spun 1 mile of filament and will be completely encased in a cocoon.

- After this entire process, the silkworm metamorphoses into a moth, but is usually killed by heat before it reaches the moth stage – any silkworm reaching the moth stage is used for breeding the next generation of silkworms.

Process to obtain filament silk

- Cocoons that have been stifled are sorted by fiber size, fiber quality, and defects, then are brushed to find filaments.

- Several filaments are gathered together and wound onto a wheel (reeling).

- Each cocoon yields 1000 yards of silk filament, known as raw silk, or silk-in-the gum, fiber.

- Several filaments are combined to form a yarn.

- As fibers are combined and wrapped into the reel, twist can be added to hold the filaments together.

- Adding twist is referred to as ‘throwing’ – resulting yarn is called thrown yarn

- The type of yarn and amount of twist relate to the fabric produced.

- The simplest type of thrown yarn is a ‘single’ – 8 filaments are twisted together to form a yarn

- Used for filling yarns in silk fabrics, singles can have 2 or 3 twists per inch

Silk noils (silk waste): produced from the inner portions of the cocoon. It is degummed (sericin is removed) and spun like other staple fiber. Or it can also be blended with another staple fiber and is spun into yarn.

Wild silk production is not controlled. Cocoons are harvested after the moth has matured, so silk cannot be reeled – it must be spun.

- Turkeye.Urgüp03.jpg

Silk filaments after dyeing

- Turkeye.Urgüp04.jpg

Reeling of the silk filaments onto a wheel

Types of wild silk

- Tussah (most common)

- Dupioni

- Momme (standard way to describe silk fabrics)

Producers

With over 30 countries producing silk the major producers are:

- China (54%)

- India (14%)

- Japan (11%)

See also

- Mommes, the traditional density unit for silk.

- Rayon

- Art silk

- Silk Road

- Spider silk (with a discussion of synthetic silk)

- Tenun Pahang Diraja, famous woven silk fabric of Pahang, Malaysia.

- Jim Thompson, pioneer of Thailand's silk industry.

- Marisol Deluna, American fashion designer known for her use of silk

- Rajshahi Silk, famous silk clothing (especially saree) of Bangladesh

- Silk in the Indian subcontinent

- History of silk

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Chinese archaeologists make ground-breaking textile discovery in 2,500-year-old tomb - Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- ↑ Annotated Translation of the Chapter on the Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu - Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- ↑ Odyssey 19 233-234: Τον δε χιτων' ενοησα περι χροισιγαλοεντα, / οιον τε κρομυοιο λοπον κατα σιγαλοεντα = "And I [= Odysseus, pretending to be someone else when talking to his wife Penelope when he came back to Ithaca ] noted the tunic about his [= Odysseus's] body, all shining like the skin of a dried onion."

- ↑ Cornelius Tacitus. The reign of Tiberius : out of the first six annals of Tacitus, with his account of Germany, and life of Agricola. (London: W. Scott, 1890, OCLC 3489328)

- ↑ Silk: Why It Is Haram for Men - Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- ↑ Down and Silk: Birds and Insects Exploited for Fabric - Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- ↑ History of Sericulture, Culture Entomology Digest 1 - Retrieved November 15, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- On the question of silk in pre-Han Eurasia - Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- The Peoples of the West from the Weilue - Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- Silk Weaving in Ancient China: From Geometric Figures to Patterns of Pictorial Likeness - Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- Lui, Hsin-ju. 1996. Silk and religion an exploration of material life and the thought of people, AD 600-1200. Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195636554

- Sung, Ying-Hsing. 1637. Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century - T'ien-kung K'ai-wu. Translated and annotated by E-tu Zen Sun and Shiou-chuan Sun. Pennsylvania State University Press, 1966. Reprint: Dover, 1997. Chap. 2. Clothing materials.

- Kadolph, Sara J. 2007. Textiles. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0131187694 P.76-81.

External links

All links retrieved November 15, 2007.

- THE SILKWORMA germline transgenic silkworm that secretes recombinant proteins in the sericin layer of cocoon

- References to silk by Roman and Byzantine writers

- A series of maps depicting the global trade in silk

- History of traditional silk martial arts uniforms

- Silk production and handloom weaving

- Comparison of Silks for Embroidery - article with photos comparing different silks used in hand embroidery

| ||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.