Difference between revisions of "Malaysia" - New World Encyclopedia

Mike Butler (talk | contribs) m |

m ({{Contracted}}) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Contracted}} | ||

{{Infobox_Country or territory | {{Infobox_Country or territory | ||

|native_name = Malaysia<br /><span style="line-height:1.33em;">مليسيا</span> | |native_name = Malaysia<br /><span style="line-height:1.33em;">مليسيا</span> | ||

Revision as of 18:41, 15 January 2007

| Malaysia مليسيا | |||||

| |||||

| Motto: Bersekutu Bertambah Mutu (English: "Unity Is Strength")[1] | |||||

| Anthem: "Negaraku" | |||||

| Capital | Kuala Lumpur1 3°08′N 101°42′E | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Largest city | Kuala Lumpur | ||||

| Official languages | Malay | ||||

| Government | Federal constitutional monarchy | ||||

| - Paramount Ruler | Sultan Mizan Zainal Abidin | ||||

| - Prime Minister | Abdullah Ahmad Badawi | ||||

| Independence | |||||

| - from the UK (Malaya only) | August 31 1957 | ||||

| - Federation (with Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore2) | September 16 1963 | ||||

| Area | |||||

| - Total | 329,847 km² (67th) 127,355 sq mi | ||||

| - Water (%) | 0.3 | ||||

| Population | |||||

| - Dec. 2006 estimate | 26,888,000 | ||||

| - 2000 census | 23,953,136 | ||||

| - Density | 82/km² 211/sq mi | ||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2006 estimate | ||||

| - Total | $290.7 billion | ||||

| - Per capita | $12,100 | ||||

| HDI (2006) | 0.805 (high) | ||||

| Currency | Ringgit (RM) (MYR)

| ||||

| Time zone | MST (UTC+8) | ||||

| - Summer (DST) | not observed (UTC+8) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .my | ||||

| Calling code | +60 | ||||

| 1 Putrajaya is the primary seat of government. 2 Singapore became an independent country on 9 August 1965. | |||||

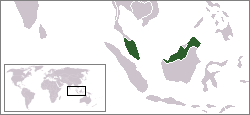

Malaysia is a federation of thirteen states in Southeast Asia.[2] The country consists of two geographical regions divided by the South China Sea[3]:

- Peninsular Malaysia (or West Malaysia) on the Malay Peninsula shares a land border on the north with Thailand and is connected by the Johor-Singapore Causeway and the Malaysia-Singapore Second Link to the south with Singapore. It consists of nine sultanates (Johor, Kedah, Kelantan, Negeri Sembilan, Pahang, Perak, Perlis, Selangor and Terengganu), two states headed by governors (Malacca and Penang), and two federal territories (Putrajaya and Kuala Lumpur).[4]

- Malaysian Borneo (or East Malaysia) occupies the northern part of the island of Borneo, bordering Indonesia and surrounding the Sultanate of Brunei. It consists of the states of Sabah and Sarawak and the federal territory of Labuan.[4]

The name "Malaysia" was adopted in 1963 when the Federation of Malaya (Malay: Persekutuan Tanah Melayu), Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak formed a 14-state federation.[5] Singapore was expelled from the federation in 1965 and subsequently become an independent country.[6]

Although politically dominated by the Malays, modern Malaysian society is heterogeneous, with substantial Chinese and Indian minorities.[7] Malaysian politics have been noted for their allegedly communal nature[8]; the three major component parties of the Barisan Nasional each restrict membership to those of one ethnic group. However, the only major intercommunal violence the country has seen since independence was the May 13 racial riots of 1969 that occurred in the wake of an election campaign that was dominated by racial issues.[9]

History

The Malay Peninsula has thrived from its central position in the maritime trade routes between China and the Middle East. Ptolemy showed it on his early map with a label that translates as "Golden Chersonese", the Straits of Malacca were referred to as "Sinus Sabaricus".

The earliest recorded Malay kingdoms grew from coastal city-ports established in the 10th century AD. These include Langkasuka and Lembah Bujang in Kedah, as well as Beruas and Gangga Negara in Perak and Pan Pan in Kelantan. It is thought that originally these were Hindu or Buddhist nations. The first evidence of Islam in the Malay peninsula dates from the 14th century in Terengganu, but according to the Kedah Annals, the 9th Maharaja Derbar Raja (1136-1179 C.E.) of Sultanate of Kedah converted to Islam and changed his name to Sultan Muzaffar Shah. Since then there have been 27 Sultans who ruled Kedah.

There were numerous Malay kingdoms in the 2nd and 3rd century C.E., as many as 30 according to Chinese sources. Kedah – known as Kedaram or Kataha, in ancient Pallava or Sanskrit – was in the direct route of invasions of Indian traders and kings. Rajendra Chola, who is now thought to have laid Kota Gelanggi to waste, put Kedah to heel in 1025 but his successor, Vir Rajendra Chola, had to put down a Kedah rebellion to overthrow the invaders.

The Buddhist kingdom of Ligor took control of Kedah shortly after, and its King Chandrabhanu used it as a base to attack Sri Lanka in the 11the century, an event noted in a stone inscription in Nagapattinum in Tamil Nadu and in the Sri Lankan epic, Mahavamsa. During the first millennium, the people of the Malay peninsula adopted Hinduism and Buddhism and the use of the Sanskrit language until they eventually converted to Islam, but not before Hinduism, Buddhism and Sanskrit became embedded into the Malay worldview. Traces of the influences in political ideas, social structure, rituals, language, arts and cultural practices still can be seen to this day.

There are reports of other areas older than Kedah – the ancient kingdom of Ganganegara, around Bruas in Perak, for instance – that pushes Malaysian history even further into antiquity. If that is not enough, a Tamil poem, Pattinapillai, of the second century C.E., describes goods from Kadaram heaped in the broad streets of the Chola capital; a seventh century Sanskrit drama, Kaumudhimahotsva, refers to Kedah as Kataha-nagari. The Agnipurana also mentions a territory known Anda-Kataha with one of its boundaries delineated by a peak, which scholars believe is Gunong Jerai. Stories from the Katasaritasagaram describe the life of elegance of life in Kataha.

In the early 15th century, the Sultanate of Malacca was established under a dynasty founded by Parameswara, a prince from Palembang, who fled from the island Temasek (now Singapore). Parameswara decided to establish his kingdom in Malacca after witnessing an astonishing incident where a white mouse deer kicked one of his hunting dogs. He took it as a sign of good luck and name his kingdom "Melaka" after the tree where he was resting under. At its height, the sultanate controlled the areas which are now Peninsula Malaysia, southern Thailand (Patani), and the eastern coast of Sumatra. It existed for more than a century, and within that time period Islam spread to most of the Malay Archipelago. Malacca was the foremost trading port at the time in Southeast Asia.[10]

In 1511, Malacca was conquered by Portugal, which established a colony there. The sons of the last sultan of Malacca established two sultanates elsewhere in the peninsula - the Sultanate of Perak to the north, and the Sultanate of Johor (originally a continuation of the old Malacca sultanate) to the south. After the fall of Malacca, three nations struggled for the control of Malacca Strait: the Portuguese (in Malacca), the Sultanate of Johor, and the Sultanate of Aceh. This conflict went on till 1641, when the Dutch (allied to the Sultanate of Johor) gained control of Malacca.

Britain established its first colony in the Malay peninsula in 1786, with the lease of the island of Penang to the British East India Company by the Sultan of Kedah. In 1824, the British took control of Malacca following the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 which divided the Malaya archipelago between Britain and the Netherlands, with Malaya in the British zone. In 1826, Britain established the crown colony of the Straits Settlements, uniting its three possessions in Malaya: Penang, Malacca and Singapore. The Straits Settlements were administered under the East India Company in Calcutta until 1867, when they were transferred to the Colonial Office in London.

During the late 19th century, many Malay states decided to obtain British help in settling their internal conflicts. The commercial importance of tin mining in the Malay states to merchants in the Straits Settlements led to British government intervention in the tin-producing states in the Malay Peninsula. British gunboat diplomacy was employed to bring about a peaceful resolution to civil disturbances caused by Chinese gangsters, and the Pangkor Treaty of 1874 paved the way for the expansion of British influence in Malaya. By the turn of the 20th century the states of Pahang, Selangor, Perak, and Negeri Sembilan, known together as the Federated Malay States (not to be confused with the Federation of Malaya), were under the de facto control of British Residents appointed to advise the Malay rulers. The British were "advisers" by name but in reality they were the puppet masters behind the Malay rulers.

The remaining five states in the peninsula, known as the Unfederated Malay States, while not directly under rule from London, also accepted British advisors around the turn of the 20th century. Of these, the four northern states of Perlis, Kedah, Kelantan and Terengganu had previously been under Siamese control.

On the island of Borneo, Sabah was governed as the crown colony of British North Borneo, while Sarawak was acquired from Brunei as the personal kingdom of the Brooke family, who ruled as White Rajahs.

Following the Japanese occupation of Malaya (1942-1945) during World War II, popular support for independence grew.[11] Post-war British plans to unite the administration of Malaya under a single crown colony called the Malayan Union foundered on strong opposition from the Malays, who opposed the emasculation of the Malay rulers and the granting of citizenship to the ethnic Chinese.[12] The Malayan Union, established in 1946 and consisting of all the British possessions in Malaya with the exception of Singapore, was dissolved in 1948 and replaced by the Federation of Malaya, which restored the autonomy of the rulers of the Malay states under British protection.

During this time, rebels under the leadership of the Communist Party of Malaya launched guerrilla operations designed to force the British out of Malaya. The Malayan Emergency, as it was known, lasted from 1948 to 1960, and involved a long anti-insurgency campaign by Commonwealth troops in Malaya.[13] Against this backdrop, independence for the Federation within the Commonwealth was granted on 31 August 1957.[14]

In 1963 the Federation was renamed Malaysia with the admission of the then-British crown colonies of Singapore, Sabah (British North Borneo) and Sarawak. The Sultanate of Brunei, though initially expressing interest in joining the Federation, withdrew from the planned merger due to opposition from certain segments of the population as well as arguments over the payment of oil royalties and the status of the Sultan in the planned merger.[15][16]

The early years of independence were marred by conflict with Indonesia (Konfrontasi) over the formation of Malaysia, Singapore's eventual exit in 1965, and racial strife in the form of racial riots in 1969.[9][17] The Philippines also made an active claim on Sabah in that period based upon the Sultanate of Brunei's cession of its north-east territories to the Sultanate of Sulu in 1704. The claim is still ongoing.[18]

After the May 13 racial riots of 1969, the controversial New Economic Policy - intended to increase the share of the economic pie owned by the bumiputras ("indigenous people", which includes the majority Malays, but not always the indigenous population) as opposed to other ethnic groups - was launched by Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak. Malaysia has since maintained a delicate ethno-political balance, with a system of government that has attempted to combine overall economic development with political and economic policies that favour Bumiputras.[19]

Between the 1980s and the mid 1990s, Malaysia experienced significant economic growth under the premiership of Tun Dr Mahathir bin Mohamad.[20] The period saw a shift from an agriculture-based economy to one based on manufacturing and industry in areas such as computers and consumer electronics. It was during this period, too, that the physical landscape of Malaysia has changed with the emergence of numerous mega-projects. The most notable of these projects are the Petronas Twin Towers (at the time the tallest building in the world), KL International Airport (KLIA), the Sepang F1 Circuit, the Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC), the Bakun hydroelectric dam and Putrajaya, a new federal administrative capital.

In the late 1990s, Malaysia was shaken by the Asian financial crisis as well as political unrest caused by the sacking of the deputy prime minister Dato' Seri Anwar Ibrahim.[21] In 2003, Dr Mahathir, Malaysia's longest serving prime minister, retired in favour of his deputy, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, commonly known as Pak Lah.[22]

Politics

Malaysia is a federal constitutional elective monarchy. The federal head of state of Malaysia is the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, commonly referred to as the King of Malaysia. The Yang di-Pertuan Agong is elected to a five-year term among the nine hereditary Sultans of the Malay states; the other four states, which have titular Governors, do not participate in the selection.[23]

The system of government in Malaysia is closely modeled on that of Westminster parliamentary system, a legacy of British colonial rule. In practice however, more power is vested in the executive branch of government than in the legislative, and the judiciary has been weakened by sustained attacks by the government during the Mahathir era. Since independence in 1957, Malaysia has been governed by a multi-party coalition known as the Barisan Nasional (formerly known as the Alliance). [24]

Legislative power is divided between federal and state legislatures. The bicameral parliament consists of the lower house, the House of Representatives or Dewan Rakyat (literally the "Chamber of the People") and the upper house, the Senate or Dewan Negara (literally the "Chamber of the Nation").[25][26][27] The 219-member House of Representatives are elected from single-member constituencies that are drawn based on population for a maximum term of 5 years. All 70 Senators sit for 3-year terms; 26 are elected by the 13 state assemblies, 2 representing the federal territory of Kuala Lumpur, 1 each from federal territories of Labuan and Putrajaya, and 40 are appointed by the king. Besides the Parliament at the federal level, each state has a unicameral state legislative chamber (Malay:Dewan Undangan Negeri) whose members are elected from single-member constituencies. Parliamentary elections are held at least once every five years, with the last general election being in March 2004.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag The cabinet is chosen from among members of both houses of Parliament and is responsible to that body.[28]

The state governments are led by chief ministers (Menteri Besar in Malay states or Ketua Menteri in states without hereditary rulers), selected by the state assemblies (Dewan Undangan Negeri) advising their respective sultans or governors. [citation needed]

Geography

The two distinct parts of Malaysia, separated from each other by the South China Sea, share a largely similar landscape in that both West and East Malaysia feature coastal plains rising to often densely forested hills and mountains, the highest of which is Mount Kinabalu at 4,095.2 metres (13,435.7 ft) on the island of Borneo. The local climate is equatorial and characterised by the annual southwest (April to October) and northeast (October to February) monsoons.

Tanjung Piai, located in the southern state of Johor, is the southernmost tip of continental Asia.[29][30]

The Strait of Malacca, lying between Sumatra and Peninsular Malaysia, is arguably the most important shipping lane in the world.[31]

Putrajaya is the newly created administrative capital for the federal government of Malaysia, aimed in part to ease growing congestion within Malaysia's capital city, Kuala Lumpur. Kuala Lumpur remains the seat of parliament, as well as the commercial and financial capital of the country. Other major cities include Georgetown, Ipoh, Johor Bahru, Kuching, Kota Kinabalu, Alor Star and Malacca Town.

Economy

The Malay Peninsula and indeed Southeast Asia has been a centre of trade for centuries. Various items such as porcelain and spice were actively traded even before Malacca and Singapore rose to prominence.

In the 17th century, large deposits of tin were found in several Malay states. Later, as the British started to take over as administrators of Malaya, rubber and palm oil trees were introduced for commercial purposes. Over time, Malaya became the world's largest major producer of tin, rubber, and palm oil.[32] These three commodities, along with other raw materials, firmly set Malaysia's economic tempo well into the mid-20th century.

Instead of relying on the local Malays as a source of labour, the British brought in Chinese and Indians to work on the mines and plantations. Although many of them returned to their respective home countries after their agreed tenure ended, some remained in Malaysia and settled permanently.

As Malaya moved towards independence, the government began implementing economic five-year plans, beginning with the First Malayan Five Year Plan in 1955. Upon the establishment of Malaysia, the plans were re-titled and renumbered, beginning with the First Malaysia Plan in 1965.

In 1970s, Malaysia began to imitate the footsteps of the original four Asian Tigers and committed itself to a transition from being reliant on mining and agriculture to an economy that depends more on manufacturing. With Japanese investment, heavy industries flourished and in a matter of years, Malaysian exports became the country's primary growth engine. Malaysia consistently achieved more than 7% GDP growth along with low inflation in the 1980s and the 1990s.

During the same period, the government tried to eradicate poverty with the controversial New Economic Policy (NEP), after the May 13 Incident of racial rioting in 1969. Its main objective was the elimination of the association of race with economic function, and the first five-year plan to begin implementing the NEP was the Second Malaysia Plan. The success or failure of the NEP is the subject of much debate, although it was officially retired in 1990 and replaced by the National Development Policy (NDP).

The rapid economic boom led to a variety of supply problems, however. Labour shortages soon resulted in an influx of millions of foreign workers, many illegal. Cash-rich PLCs and consortiums of banks eager to benefit from increased and rapid development began large infrastructure projects. This all ended when the Asian Financial Crisis hit in the fall of 1997, delivering a massive shock to Malaysia's economy.

As with other countries affected by the crisis, there was speculative short-selling of the Malaysian currency, the ringgit. Foreign direct investment fell at an alarming rate and, as capital flowed out of the country, the value of the ringgit dropped from MYR 2.50 per USD to, at one point, MYR 4.80 per USD. The Kuala Lumpur Stock Exchange's composite index plummeted from approximately 1300 points to nearly merely 400 points in a matter of weeks. After the controversial sacking of finance minister Anwar Ibrahim, a National Economic Action Council was formed to deal with the monetary crisis. Bank Negara imposed capital controls and pegged the Malaysian ringgit at 3.80 to the US dollar. Malaysia refused economic aid packages from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, however, surprising many analysts.

In March 2005, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) published a paper on the sources and pace of Malaysia's recovery, written by Jomo K.S. of the applied economics department, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur. The paper concluded that the controls imposed by Malaysia's government neither hurt nor helped recovery. The chief factor was an increase in electronics components exports, which was caused by a large increase in the demand for components in the United States, which was caused, in turn, by a fear of the effects of the arrival of the year 2000 (Y2K) upon older computers and other digital devices.

However, the post Y2K slump of 2001 did not affect Malaysia as much as other countries. This may have been clearer evidence that there are other causes and effects that can be more properly attributable for recovery. One possibility is that the currency speculators had run out of finance after failing in their attack on the Hong Kong dollar in August 1998 and after the Russian ruble collapsed. (See George Soros)

Regardless of cause/effect claims, rejuvenation of the economy also coincided with massive government spending and budget deficits in the years that followed the crisis. Later, Malaysia enjoyed faster economic recovery compared to its neighbours. In many ways, however, the country has yet to recover to the levels of the pre-crisis era.

While the pace of development today is not as rapid, it is seen to be more sustainable. Although the controls and economic housekeeping may not have been the principal reason for recovery, there is no doubt that the banking sector has become more resilient to external shocks. The current account has also settled into a structural surplus, providing a cushion to capital flight. Asset prices are now a fraction of their pre-crisis heights.

The fixed exchange rate was abandoned in July 2005 in favour of a managed floating system within an hour of China's announcing of the same move. In the same week, the ringgit strengthened a percent against various major currencies and was expected to appreciate further. As of December 2005, however, expectations of further appreciation were muted as capital flight exceeded USD 10 billion.[33]

In September 2005, Sir Howard J. Davies, director of the London School of Economics, at a meeting Kuala Lumpur, cautioned Malaysian officials that if they want a flexible capital market, they will have to lift the ban on short-selling put into effect during the crisis. On March 23 2006, Malaysia removed the ban on short selling. [34]

Natural resources

Malaysia is well-endowed with natural resources in areas such as agriculture, forestry as well as minerals. In terms of agriculture, Malaysia is the world's primary exporter of natural rubber and palm oil, which together with saw logs and sawn timber, cocoa, pepper, pineapple and tobacco dominate the growth of the sector. Palm oil is also a major foreign exchange earner.

Regarding forestry resources, it is noted that logging only began to make a substantial contribution to the economy during the nineteenth century. Today an estimated 59% of Malaysia remains forested. The rapid expansion of the timber industry, particularly after the 1960s, has brought about a serious erosion problem in the country's forest resources. However, in line with the Government's commitment to protect the environment and the ecological system, forestry resources are being managed on a sustainable basis and accordingly the rate of tree felling has been on the downtrend.

In addition, substantial areas are being silviculturally treated and reforestation of degraded forest land is also being carried out. The Malaysian government provide plans for the enrichment of some 312.30 square kilometres (120.5 sq mi) of land with rattan under natural forest conditions and in rubber plantations as an intercrop. To further enrich forest resources, fast-growing timber species such as meranti tembaga, merawan and sesenduk are also being planted. At the same time, the cultivation of high-value trees like teak and other trees for pulp and paper are also encouraged. Rubber, once the mainstay of the Malaysian economy, has been largely replaced by oil palm as Malaysia's leading agricultural export.

Tin and petroleum are the two main mineral resources that are of major significance in the Malaysian economy. Malaysia was once the world's largest producer of tin until the collapse of the tin market in the early 1980s. In the 19th and 20th century, tin played a predominant role in the Malaysian economy. It was only in 1972 that petroleum and natural gas took over from tin as the mainstay of the mining sector. Meanwhile, the contribution by tin has declined. Petroleum and natural gas which were discovered in oilfields offshore Sabah, Sarawak and Terengganu have contributed much to the Malaysian economy particularly in those three states. Other minerals of some importance or significance include copper, gold, bauxite, iron-ore and coal together with industrial minerals like clay, kaolin, silica, limestone, barite, phosphates and dimension stones such as granite as well as marble blocks and slabs. Small quantities of gold are produced.

In 2004, Minister in the Prime Minister's Department, Datuk Mustapa Mohamed, revealed that Malaysia's oil reserves stood at 4.84 billion barrels while natural gas reserves increased to 89 trillion cubic feet (2,500 km³). This was an increase of 7.2%.[citation needed]

The government estimates that at current production rates Malaysia will be able to produce oil up to 18 years and gas for 35 years. In 2004 Malaysia is ranked 24th in terms of world oil reserves and 13th for gas. 56% of the oil reserves exist in the Peninsula while 19% exist in East Malaysia. The government collects oil royalties of which 5% are passed to the states and the rest retained by the federal government.[citation needed]

Transportation and communications

Malaysia has extensive roads that connect all major cities and towns on the western coast of Peninsular Malaysia. The total length of the Malaysian expressway network is 1,192 kilometres (740 miles). The network connects all major cities and conurbations such as Klang Valley, Johor Bahru and Penang to each other. The major expressway, the North-South Expressway spans from the northern and the southern tips of Peninsular Malaysia at Bukit Kayu Hitam and Johor Baru respectively. It is a part of the Asian Highway Network, which also connects into Thailand and Singapore.

Roads in the East Malaysia and the eastern coast of Peninsular Malaysia are still relatively undeveloped. Those are highly curved roads passing through mountainous regions and many are still unsealed, gravel roads. This has resulted in the continued use of rivers as the main mode of transportation for interior residents.

Train service in West Malaysia is operated by the Keretapi Tanah Melayu (Malayan Railways) and has extensive railroads that connect all major cities and towns on the peninsular, including Singapore. There is also a short railway in Sabah operated by North Borneo Railway that mainly carries freight.

There are sea ports in Tanjong Kidurong, Kota Kinabalu, Kuching, Kuantan, Pasir Gudang, Tanjung Pelepas, Penang, Port Klang, Sandakan and Tawau.

There are also world class airports, such as Kuala Lumpur International Airport in Sepang, Bayan Lepas International Airport in Penang, Kuching International Airport and Langkawi International Airport that provide international and domestic destinations. There are also airports in smaller towns as well as small domestic airstrips in rural Sabah and Sarawak. There are daily flight services between West and East Malaysia, which is the only option for passengers traveling between the two parts of the country, as well as regular flight services to international destinations. Malaysia is the home of the first low-cost carrier in the region, Air Asia. It has Kuala Lumpur as its hub and maintains flights around Southeast Asia and China as well. In KL it operates out of the Low Cost Carrier Terminal (LCCT).

The intercity telecommunication service is provided on Peninsular Malaysia mainly by microwave radio relay. International telecommunications are provided through submarine cables and satellite. One of the largest and most significant telecommunication companies in Malaysia is Telekom Malaysia Berhad (TM), providing products and services from fixed line, mobile as well as dial-up and broadband Internet access service. It has the near-monopoly of fixed line phone service in the country.

In December 2004, Energy, Water and Communications Minister Datuk Seri Dr Lim Keng Yaik reported that only 0.85% or 218,004 people in Malaysia used broadband services. However these values are based on subscriber number, whilst household percentage can reflect the situation more accurately. This represented an increase from 0.45% in three quarters. He also stated that the government targeted usage of 5% by 2006 and doubling to 10% by 2008. Lim Keng Yaik had urged local telecommunication companies and service provider to open up the last mile and lower prices to benefit the users.

Healthcare

Malaysian society places importance on the expansion and development of healthcare, putting 5% of the government social sector development budget into public healthcare — an increase of more than 47% over the previous figure. This has meant an overall increase of more than RM 2 billion. With a rising and aging population, the Government wishes to improve in many areas including the refurbishment of existing hospitals, building and equipping new hospitals, expansion of the number of polyclinics, and improvements in training and expansion of telehealth. Over the last couple of years they have increased their efforts to overhaul the systems and attract more foreign investment.

The Malaysian healthcare system requires doctors to perform a compulsory 3 years service with public hospitals to ensure the manpower of these hospitals is maintained. Recently foreign doctors have also been encouraged to take up employment here. There is still, however, a compound shortage of medical workforce, especially that of highly trained specialists resulting in certain medical care and treatment only available in large cities. Recent efforts to bring many facilities to other towns have been hampered by lack of expertise to run the available equipment made ready by investments.

There are currently 115 government hospitals and healthcare centres with a total of 28,163 beds. There are also seven special medical institutions (including psychiatric institutions) with a total of 6,292 beds. As for private hospitals, there are 225 of them (including maternity and nursing homes) in Malaysia, and they provide 9,498 beds. The majority are in urban areas and, unlike many of the public hospitals, are equipped with the latest diagnostic and imaging facilities. Private hospitals have not generally been seen as an ideal investment - it has often taken up to 10 years before companies have seen any profits. However, the situation has now changed and companies are now looking into this area again, particularly in view of the increasing interest by foreigners in coming to Malaysia for medical care.

Education

Education in Malaysia is monitored by the federal government Ministry of Education.[35]

Most Malaysian children start schooling between the ages of 3 to 6, in kindergarten. Most kindergartens run privately, as well as some government-operated kindergartens.

Children begin primary schooling at age of 7 for six years. There are two major types of government-operated or government-assisted primary schools: national schools (Sekolah Kebangsaan) which uses Malay as medium of instruction, and national-type schools (Sekolah Jenis Kebangsaan) which uses either Chinese or Tamil as medium of instruction. Before progressing to secondary level, students in Year 6 sit for the Ujian Pencapaian Sekolah Rendah (UPSR), or Primary School Assessment Examination. An exam called Penilaian Tahap Satu (PTS), First Level Assessment, was used to measure the ability of bright students, and to allow them to move from Year 3 to 5, skipping Year 4.[36] The exam was removed in 2001.

Secondary education in government secondary schools lasts five years. Government secondary schools uses Malay as medium of instruction apart from language, Mathematics and Science subjects. At the end of the third year or Form Three, students sit for the Penilaian Menengah Rendah (PMR), Lower Secondary Assessment. The combination of subjects available to Form 4 students vary from one school to another. In the last year (Form 5), students sit for Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia (SPM), Malaysian Certificate of Education, which is equivalent to the British Ordinary or 'O' Levels, now referred to as GCSE.

Mathematics and Science subjects in government primary and secondary schools such as Biology, Physics, Chemistry are taught in English. The reasoning was that students would no longer be hindered by the language barrier during their tertiary education in fields such as medicine and engineering.

There are also 60 Chinese Independent High Schools in Malaysia, where most subjects are instructed in Chinese. Chinese Independent High Schools are monitored and standardized by the United Chinese School Committees' Association of Malaysia (UCSCAM, more commonly referred to by its Chinese name, Dong Zong 董总), however, unlike government schools, every independent school is free to make its own decisions. Studying in independent schools takes 6 years to complete, divided into Junior Middle (3 years) and Senior Middle (3 years). Students sit for a standardised test by Dong Zong known as the Unified Examination Certificate (UEC) in Junior Middle 3 (equivalent to PMR) and Senior Middle 3 (equivalent to AO level). A number of independent schools conduct classes in Malay and English in addition to Chinese, enabling the students to sit for the PMR and SPM as well.

Students wishing to enter public universities must complete 1 1/2 more years of secondary schooling in Form Six and sit for the Sijil Tinggi Pelajaran Malaysia (STPM), Malaysia Higher Certificate of Education; equivalent to the British Advanced or 'A' levels.

As for tertiary education, there are public universities such as University of Malaya and Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. In addition, 5 international reputable universities have set up their branch campuses in Malaysia since 1998. A branch campus can be seen as an ‘off-shore’ of the foreign university, which offers the same courses and awards as at the ‘headquarters’. Both local and international students can acquire these identical foreign qualifications at a much lower education cost in Malaysia. The foreign university branch campuses in Malaysia are: Monash University (Sunway Campus), Curtin University of Technology (Sarawak Campus), Swinburne University of Technology Sarawak Campus, University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus and FTMS-De Monfort University Campus of Malaysia in Kuala Lumpur.

Students can also opt to go to private colleges after secondary studies. Most colleges have educational links with overseas universities especially in the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia. Malaysian students abroad study mostly in the UK, United States, Australia, Singapore, South Korea, Japan, Canada and New Zealand.

In addition to the National Curriculum, Malaysia has many international schools. International schools offer students the opportunity to study the curriculum of another country. These schools mainly cater to the growing expatriate population in the country. International schools include - Australian International School, Malaysia (Australian curriculum), The Alice Smith School (British curriculum), The Garden International School (British curriculum), The International School of Kuala Lumpur (International Baccalaureate and American curriculum), The Japanese School of Kuala Lumpur (Japanese curriculum),The International School of Penang (International Baccalaureate and British curruculum) Lycée Français de Kuala Lumpur (French curriculum) amongst others.

Demographics

Malaysia's population is comprised of many ethnic groups, with the politically dominant Malays making up the majority, close to 60% of the population. By constitutional definition, all Malays are Muslim. About 30% of the population are Malaysians of Chinese descent, who have historically played an important role in trade and business. Malaysians of Indian descent comprise about 8% of the population. About 90% of the Indian community is Tamil but various other groups are also present, including Malayalis, Punjabis and Gujaratis.

Non-Malay indigenous groups make up more than half of the state of Sarawak's population, constitute about 66% of Sabah's population, and also exist in much smaller numbers on the Peninsula, where they are collectively called Orang Asli. The non-Malay indigenous population is divided into dozens of ethnic groups, but they share some general cultural similarities. Other Malaysians also include those of, inter alia, European, Middle Eastern, Cambodian, and Vietnamese descent. Europeans and Eurasians include British who colonized and settled in Malaysia and some Portuguese, and most of the Middle Easterners are Arabs. A small number of Kampucheans and Vietnamese settled in Malaysia as Vietnam War refugees. Population distribution is uneven, with some 20 million residents concentrated on the Malay Peninsula.

May 13, 1969 saw an incident of civil unrest which was then thought to be largely due to the socio-economic imbalance of the country along racial lines, though in retrospect it may have been more motivated by political firebrands in both governing and opposition parties, as the violence involved only the areas in and around the capital, with much of the country remaining at peace. This incident led to the adoption of the New Economic Policy as a two-pronged approach to address racial and economic inequality and to eradicate poverty in the country.

Due to the rise in labour intensive industries, Malaysia has 10 to 20% foreign workers with the uncertainty due in part to the large number of illegal workers, mostly Indonesian; there are a million legal foreign workers and perhaps another million unauthorized foreigners. The state of Sabah alone has nearly 25% of its 3 million population listed as illegal foreign workers in the last census. However, this figure of 25% is thought to be less than half the figure speculated by NGOs.[37] Unauthorized foreigners are subject to RM10,000 fines and two-year prison terms, while Malaysian employers face up to a year in jail and a fine of up to RM50,000 for each illegal worker hired, with those hiring more than five also liable to caning. Caning is a standard punishment for more than 40 crimes in Malaysia, ranging from sexual abuse to drug use. Administered with a thick rattan stick, it splits the skin and leaves scars.

Some 380,000 unauthorized foreigners left during an "amnesty" that began in 2004 and was extended several times. During amnesties, unauthorized foreigners can leave without paying fines for staying illegally in the country. On March 1, 2005, some 300,000 policemen as well as the 560,000-strong Peoples Volunteer Corp began searching for the remaining unauthorized foreigners under Operation Tegas; the volunteers receive RM100 for each foreigner arrested. [38]

Religion

Malaysia is a multi-religious society, and Islam is the country's official religion. The four main religions are Islam (60% of the population), Buddhism (19%), Christianity (9.1%, mostly in Sabah and Sarawak), and Hinduism (6.3%), according to government census figures in 2004. Until the 20th century, most practiced traditional beliefs, which arguably still linger on to a greater degree than Malaysian officialdom is prepared to acknowledge. The aforementioned figures may be skewed as they do not take into account the fact that all Malay persons are officially regarded and treated as Muslim, regardless of private belief.[39]

Although the Malaysian constitution theoretically guarantees religious freedom, in practice the situation is not so simple (See Status of religious freedom in Malaysia). Non-Muslims often experience restrictions in activities such as construction of religious buildings and the celebration of certain religious events in some Islamic states [40] [41]. Meanwhile Muslims are obliged to follow the decisions of sharia courts. As a legal matter, it is not yet clear whether Muslims may freely leave Islam. In some situations, the Malaysian courts have denied one's right to freedom of religion even when one has renounced Islam (such as the Joshua Jamaluddin versus the Minister of Home Affairs case in the 1980s).[42] Generally one who wishes to leave Islam makes a legal declaration, but this is still not recognised by the Malaysian civil courts. One is said to have to obtain a declaration of apostasy with a Sharia Court, but the court will not grant one.

Malaysians tend to personally respect one another's religious beliefs, with inter-religious problems arising mainly from the political sphere.

- Islam in Malaysia

- Buddhism in Malaysia

- Christianity in Malaysia

- Hinduism in Malaysia

- Status of religious freedom in Malaysia

Culture

Malaysia is a multi-ethnic, multi-cultural and multilingual society, consisting of 65% Malays and other indigenous tribes, 25% Chinese, 7% Indians. The Malays, which form the largest community, are defined as Muslims in the Constitution of Malaysia. The Malays play a dominant role politically and are included in a grouping identified as bumiputra. Their native language is Malay (Bahasa Melayu). Malay is the national language of the country.[43]

In the past, Malay was written widely in Jawi, a script based on Arabic. Over time, romanized script overtook Jawi as the dominant script. This was largely due to the influence of the colonial education system which taught children in romanised writing rather than in Arabic script.

The largest non-Malay indigenous tribe is the Iban of Sarawak, who number over 600,000. Some Iban still live in traditional jungle villages in longhouses along the Rajang and Lupar rivers and their tributaries, although many have moved to the cities. The Bidayuh (170,000) are concentrated in the south-western part of Sarawak. The largest indigenous tribe in Sabah is the Kadazan. They are largely Christian subsistence farmers. The Orang Asli (140,000), or aboriginal peoples, comprise a number of different ethnic communities living in Peninsular Malaysia. Traditionally nomadic hunter-gatherers and agriculturists, many have been sedentarised and partially absorbed into modern Malaysia. However, they remain the poorest group in the country.

The Chinese population in Malaysia is mostly Buddhist (of Mahayana sect), Taoist or Christian. Chinese in Malaysia speak a variety of Chinese dialects including Mandarin Chinese, Hokkien/Fujian, Cantonese, Hakka and Teochew. Many Chinese in Malaysia also speak English as a first language. Chinese have historically been dominant in the Malaysian business community.

The Indians in Malaysia are mainly Hindu Tamils from southern India, speaking Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, and Hindi, living mainly in the larger towns on the west coast of the peninsula. Many middle to upper-middle class Indians in Malaysia also speak English as a first language. There is also a sizable Sikh community in Malaysia of over 83,000. Most Indians originally migrated from India as traders, teachers or other skilled workers. A larger number were also part of the forced migrations from India by the British during colonial times to work in the plantation industry.

Eurasians, Cambodians, Vietnamese, and indigenous tribes make up the remaining population. A small number of Eurasians, of mixed Portuguese and Malay descent, speak a Portuguese-based creole, called Papiá Kristang. There are also Eurasians of mixed Malay and Spanish descent, mostly in Sabah. Descended from immigrants from the Philippines, some speak Chavacano, the only Spanish-based creole language in Asia. Cambodians and Vietnamese are mostly Buddhists (Cambodians of Theravada sect and Vietnamese, Mahayana sect).

Malaysian traditional music is heavily influenced by Chinese and Islamic forms. The music is based largely around the gendang (drum), but includes other percussion instruments (some made of shells); the rebab, a bowed string instrument; the serunai, a double-reed oboe-like instrument; flutes, and trumpets. The country has a strong tradition of dance and dance dramas, some of Thai, Indian and Portuguese origin. Other artistic forms include wayang kulit (shadow puppet theatre), silat (a stylised martial art) and crafts such as batik, weaving, and silver and brasswork.

Citizenship

Most Malaysians are granted citizenship by jus soli.[44] All Malaysians are Federal citizens with no formal citizenships within the individual states except for states & the federal territory in East Malaysia where state citizenship is privilege & distinguishable from the Peninsula. Every citizen is issued with a biometric smartchip identity card, known as MyKad, at the age of 12, and must carry the card with them. A citizen is required to present his/her identity card to the police, or in the case of an emergency, to any military personnel, to be identified. If the card cannot be produced immediately, the person technically has 24 hours under the law to produce it at the nearest police station.

Holidays

Malaysians observe a number of holidays and festivities throughout the year. Some holidays are federal gazetted public holidays and some are public holidays observed by individual states. Other festivals are observed by particular ethnic or religion groups, but are not public holidays.

The most celebrated holiday is the "Hari Merdeka" (Independence Day) on August 31 commemorating the independence of the Federation of Malaya in 1957, while Malaysia Day is only celebrated in the state of Sabah coincided with the birthday of the state minister on September 16 to commemorate the formation of Malaysia in 1963. Hari Merdeka, as well as Labour Day (May 1), the King's Birthday (first Saturday of June) and some other festivals are federal gazetted public holidays.

Muslims in Malaysia (including all Malays and other non-Malay Muslims) celebrate Muslim holidays. The most celebrated festival, Hari Raya Puasa (also called Hari Raya Aidilfitri) is the Malay translation of Eid ul-Fitr. It is generally a festival honoured by the Muslims worldwide marking the end of Ramadan, the fasting month. In addition to Hari Raya Puasa, they also celebrate Hari Raya Haji (also called Hari Raya Aidiladha, the translation of Eid ul-Adha), Awal Muharram (Islamic New Year) and Maulidul Rasul (Birthday of the Prophet).

Chinese in Malaysia typically celebrate festivals that are observed by Chinese around the world. Chinese New Year is the most celebrated among the festivals which lasts for fifteen days and ends with Chap Goh Mei. Other festivals celebrated by Chinese are the Qingming Festival, the Dragon Boat Festival and the Mid-Autumn Festival. In addition to traditional Chinese festivals, Buddhists Chinese also celebrate Vesak Day.

The majority of Indians in Malaysia are Hindus and they celebrate Deepavali (Diwali), the festival of light, while Thaipusam is a celebration which pilgrims from all over the country flock to Batu Caves. Apart from the Hindus, Sikhs celebrate the Vaisaki, the Sikh New Year.

Other festivals such as Good Friday (East Malaysia only), Christmas, Hari Gawai of the Ibans (Dayaks), Pesta Menuai (Pesta Kaamatan) of the Kadazan-Dusuns are also celebrated in Malaysia.

Despite most of the festivals are identified with a particular ethnic or religion, all Malaysians celebrate the festivities together regardless of their religions and ethnic background. For years 1996-1998, when Hari Raya Puasa and Chinese New Year coincided, a slogan Kongsi Raya, a combination of Gong Xi Fa Cai, a greeting used on the Chinese New Year, and Hari Raya (which could also mean "celebrating together" in Malay language) was coined. For years 2005-2006, the Hari Raya Puasa and Deepavali coincide, and a slogan Deepa Raya is similarly coined.

See also

Template:Malaysian Topics

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Malaysian Flag and Crest. myGovernment. Extracted September 13 2006.

- ↑ myGovernment. Federal Territories and State Governments. Retrived December 8 2006.

- ↑ CIA. The World Fact Book. Malaysia. Retrieved December 9 2006.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Article 1. Constitution of Malaysia.

- ↑ Paragraph 22. Singapore. Road to Independence. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Country Studies/Area Handbook Series. U.S. Department of the Army. Retrived December 9 2006.

- ↑ Paragraph 25. Singapore. Road to Independence. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Country Studies/Area Handbook Series. U.S. Department of the Army. Retrived December 9 2006.

- ↑ CIA. People. 2006 The World Fact Book. Retrieved December 17 2006.

- ↑ Farish Noor (2005). Page 158. Kafir R' Us. Why do we need to think beyond the Muslim-Kafir divide (Part 1). From Majapahit to Putrajaya. Silverfish Books. ISBN 983-3221-05-X

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Time Magazine. Race War in Malaysia. May 23 1969. Retrieved December 17 2006.

- ↑ M.C. Ricklefs. pp. 19. A History of Modern Indonesia. Indiana University Press. 1981. ISBN 0804721955

- ↑ Mahathir Mohamad. Our Region, Ourselves. Time Asia. May 31 1999.

- ↑ Time Magazine. Token Citizenship. May 19 1953.

- ↑ Time Magazine. Siege's End. May 2 1960.

- ↑ Time Magazine. A New Nation. September 9 1957.

- ↑ Time Magazine. Hurray for Harry. December 20 1963

- ↑ Time Magazine. Fighting the Federation. December 21 1962

- ↑ Time Magazine. The Art of Dispelling Anxiety. August 27 1965.

- ↑ Republic of the Philippines. Department of Foreign Affairs. FAQs on the ICJ Decision. Retrieved December 23 2006.

- ↑ Jomo Kwame Sundaram. UNRISD The New Economic Policy and Interethnic Relations in Malaysia. Retrieved December 23 2006.

- ↑ Anthony Spaeth. Time Magazine. Bound for Glory. December 9 1996.

- ↑ Anthony Spaeth. Time Magazine. He's the Boss. September 14 1998.

- ↑ Office of the Prime Minister of Malaysia. YAB Prime Minister's interview with CNN Talk Asia. June 5 2004. Retrieved December 23 2006.

- ↑ Article 32. Constitution of Malaysia.

- ↑ US Department of State. Malaysia. Retrieved December 30 2006.

- ↑ Article 44. Constitution of Malaysia.

- ↑ Article 45. Constitution of Malaysia.

- ↑ Article 46. Constitution of Malaysia.

- ↑ Article 43 (1). Constitution of Malaysia

- ↑ Leow Chiah Wei. Travel Times. New Straits Times. Asia's southernmost tip. Retrieved December 17 2006.

- ↑ Sager Ahmad. Travel Times. New Straits Times. Tanjung Piai, the End of Asia. Retrieved December 17 2006.

- ↑ Andrew Marshall. Time Magazine. Waterway to the World. Retrieved December 17 2006.

- ↑ Time Magazine. Rubber from Malaya. March 1 1943.

- ↑ Department of Statistics. Malaysia. Quarterly Balance of Payments Performance October - December, 2005. Retrieved December 17 2006.

- ↑ Financial Times. Malaysia relaxes short-selling ban. Extracted March 28, 2006.

- ↑ Ninth Schedule. Constitution of Malaysia.

- ↑ World Education Forum. UNESCO. Education for All 2000 Assessment Report. Malaysia. Retrieved December 17 2006.

- ↑ All Sabahans must Fight BN and UMNO. Malaysia Today (August 15, 2006).

- ↑ Migration News. April 2005 Volume 12 Number 2

- ↑ Article 160 (2). Constitution of Malaysia.

- ↑ Inter Press Service: Temple Demolitions Spell Creeping Islamisation. Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ↑ BBC : Pressure on multi-faith Malaysia. Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ↑ For another 2006 case where conversion proved impossible see: Perlez, Jane, "Once Muslim, Now Christian and Caught in the Courts", New York Times, August 24, 2006. Retrieved August 25, 2006. (written in English)

- ↑ Article 152. Constitution of Malaysia.

- ↑ Article 14. Constitution of Malaysia

Others

- 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. Malay States.

- Zainal Abidin bin Abdul Wahid; Khoo, Kay Kim; Muhd Yusof bin Ibrahim; Singh, D.S. Ranjit (1994). Kurikulum Bersepadu Sekolah Menengah Sejarah Tingkatan 2. Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. ISBN 983-62-1009-1

- Adam, Ramlah binti, Samuri, Abdul Hakim bin & Fadzil, Muslimin bin (2004). Sejarah Tingkatan 3. Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. ISBN 983-62-8285-8.

- Osborne, Milton (2000). Southeast Asia: An Introductory History. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-390-9

External links

| Malaysia Portal |

- Malaysian Department of Statistics

- State Development Office - State Development Office Wilayah Persekutuan

- myGovernment Portal - Malaysian Government Portal

- Bernama - Malaysian national news agency

- Tourism Malaysia - Malaysian tourism portal

- Travel guide to Malaysia from Wikitravel

- Malaysia Travel Guide - Malaysia travel guide

- Virtual Malaysia - The Official Portal of the Ministry of Tourism, Malaysia

- Office of the Prime Minister of Malaysia

- Radio Televisyen Malaysia - Government-owned television network

- Malaysia External Trade Development Corporation

- Small Medium Industries Development Corporation

Template:Malaysia Template:Asia Template:ASEAN

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.