Holy Orders

The term Holy Orders comes from the Latin Ordo (order) and the word holy referring to the church. Historically, an order refers to an established civil body or organization with a hierarchy. Thus the term holy order as it came into usage referred to a group with a hierarchy that is engaged in ministry in the Christian church. The term is also used more broadly, however, to refer to the hierarchy of leadership in any religious group, including but not limited to the Christian, Muslim, Buddhist, Jewish and Hindu faiths.

The responsibilities and roles held by members of holy orders vary, according to the faith, location, size and history of the religious community in which they serve. These duties include leading worship services, offering intercessional prayers, offering guidence to members of the religious community, instructing members of the community in rites, practices and scriptures of their respective faiths, ministering to the poor, sick, elderly and others requiring assistance, and a whole host of other duties. In some communities, social or political leadership is provided by the same persons who provide religious leadership.

Members of holy orders, once invested or ordained as leaders of their religious communities hold the power to make their respective religious communities thrive or founder. They are charged, by virtue of their offices, with the responsibility to lead the members of their communities of faith in the right direction, toward a clean and holy life, toward mutual support and prosperity, toward spiritual health. It is sometimes the case that the state of having been called to a holy order and being charged with a position of leadership in a particular faith may influence individuals to pursue the vitality and success of their own chosen community of faith as a priority over, and sometimes even at the expense of, others, giving rise to an unfortunate contribution to the struggle of the modern world to reach world peace.

Holy orders in Christianity

Origin

In the Christian church, the term Holy Orders has come to refer specifically to the state of being ordained by the Holy Sacrament/Mystery instituted by Jesus Christ as a tenet of faith of the Roman Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Anglican Church, by which members of the faithful are ordained and called to serve as leaders of their respective communities of faith.

He appointed twelve, that they might be with him and that he might send them out to preach and to have authority to drive out demons. Mark 3:14-15, TNIV

Early in his ministry, Jesus Christ called several individuals, most of them fishermen, to follow him and be his disciples, and they came to be known as the twelve apostles. These were his assistants and close aides. They were even given the authority to perform miracles, such as casting out demons as Jesus did. Before leaving this world, Jesus sent them to spread his gospel throughout the world, to find new disciples (John 20:21) and to be his representatives on earth.

As the apostles started their mission, the need to get help and assistance and even to nurture successors arose. They needed to ordain new converts. The ordination ritual was characterized by the laying of hands on the appointee (Acts 6:1-7). According to the theory of apostolic succession, that ritual of appointing successors and assistants is the key element of the legitimacy of the holy order of each church. As a member of a holy order, one must be ordained by someone who was himself ordained. The chain of ordination links each member of the Order back in a direct line of succession to one of the apostles. Thus, there exist a historical and spiritual connection between each member of a holy order, the apostles, and the Christ.

The effect of being ordained

Being ordained in a holy order allows one to partake in special grace as God’s minister and to receive spiritual power. That power conferred at ordination is permanent and cannot be revoked, in contrast to the power given to office holders such as archbishops or deans that is revoked immediately when the person leaves office. In the Roman Catholic church, it is a doctrine of a sacramental nature.

The hierarchy

Members of holy orders in the Catholic, Orthodox and Anglican churches are divided into three levels, the order of Bishop, the order of Priest and the order of Deacon. The bishop occupies the highest rank and is said to have the 'fullness of the order'. He is followed in the hierarchy by the priest, also known as presbyter. The lowest in the hierarchy, bearing the mission of servant is the deacon. These three levels are described as the major orders in the Catholic and Orthodox Churches. The Orthodox Church recognizes another group of orders known as the minor orders. Minor orders are composed of the reader and the subdeacon.

The Priest

The word "Priest" is a translation of a derivation of the Latin sacerdos, meaning sacrifice. The priesthood is a sacrificial ministry and the priest is the official celebrant of the eucharist, a rite following the commandment of Jesus at the Last Supper, “Do this in remembrance of me.”

In ancient Israel, the culture from which the roots of the Christian church sprung, priests were the ones in charge of the altar and the temple, and the central priests were also allowed to offer sacrifices, and instruct the people about the laws of Moses. According to the teachings of the Apostle Paul, the Christians are the priests of the new Israel. This interpretation extends to the Roman Catholics who indicate that while all Christians are priests, the one who are ordained, in the position of successor to the apostles and as stewards of the Church, have a higher status of priesthood and thus receive special grace.

Starting from the third century, the term priest was applied to bishops who were the celebrants of the Eucharist. In the fourth century, the term was given to presbyters because of their newly granted new authority to officiate the Eucharist. In the Catholic Church, priests hold only slightly less authority than bishops, and may confer all the sacraments except the sacrament of ordaining persons with holy orders. In the Orthodox Church, the priest serves at the direction of the Bishop who may confer to the priests the authority to minister in his diocese, or withdraw it, as he desires.

The Bishop

According to the tradition of apostolic succession, the order of bishop has its roots in apostolic times. Apostles appointed their successors as bishops through prayer and the laying of hands, giving them the apostolic authority and priority of rank. As the highest in rank, the can administer all of the sacrament/mysteries, and have the power to ordain priests and deacons. Under ordinary circumstances, the ordination of a bishop is usually officiated by three other bishops; only in some exceptional circumstances can a bishop be ordained by a single bishop.

The Petrine doctrine, based on Matthew 16:18-19 and other Biblical references, is a doctrine of the Roman Catholic church, which holds since Peter was appointed by Christ as the head of the church, and then martyred in Rome, that the seat of the church from that time on remained in Rome.

And I tell you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of death will not overcome it. Matthew 16:18-19, TNIV

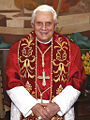

On this basis, the Roman Catholics argue that the Bishop of Rome, as the official spiritual successor of Peter, is the head of the church. The Bishop of Rome has the title of Pope, the head of the Roman Catholics Church. However, in the Orthodox Church as well as the Anglican Church, all bishops are equals and patriarchs or synods of bishops exercise only an “oversight of care” among the body of coequal bishops.

The Deacon

From Christian tradition, the order of deacon started when the apostles ordained seven men to wait on them at table (Acts 6 1-7). Deacons serve as assistants to the bishop and the minister of service. In the early days, this meant taking care of the property of the diocese, a function that was terminated during the middle ages. In the Roman Catholic church, the liturgical function of the deacon consists in helping and serving the celebrant, who leads the mass and administers the Eucharist. Many protestant churches have deacons as lay officers with no sacramental or liturgical functions.

Who can be ordained

To be ordained, an individual should feel a vocation to serve for the sake of God’s honor and for the sake of helping humanity. Generally, appointment to the holy orders is reserved for seminary graduates. It is important to note that as the elder and leader of the church, the Bishop has the last say in any ordination and often will make further inquiries about a candidate's life to ascertain his moral, intellectual and physical fitness.

Holy orders and women

In some churches women may theoretically be ordained to the same orders as men. In others, certain offices are not available for women. The Church of England (in the Anglican Communion), for example, does not permit the consecration of women as bishops, though the Episcopal Church USA (the United States branch of the Anglican Church) does. In some denominations women can be ordained as elders or deacons. The Roman Catholic Church officially teaches that it has no authority to ordain women as priests.

Holy orders and marriage

Historically the issue of marriage was a matter of personnel choice, as exemplified by the letters of Saint Paul. Celibacy was not demanded by the early Church, and St. Peter was recorded as doing his mission along with his wife. However, in later times, the Roman Catholic church came to require celibacy for its priests and bishops. By contrast, in the Orthodox Church, marriage is allowed to deacons and priests, although bishops are required to live in celibacy.

Ordination and orders in the Protestant church

There are many denominations of protestants, and likewise many variations in the process of calling and ordination to the ministry; however, there are some distinct differences between the state of being ordained in the protestant Christian church in contrast with the Catholic, Orthodox and Anglican churches. Perhaps the most important difference is that in the protestant denominations, the process of ordination affirms and lends authority to the calling to ministry, but without imparting a special spiritual state. One of the main points of the protestant reformation was that all believers have equal and direct access to God and to salvation, and that it was not necessary to approach the Lord through a mediator. The differences in ordination, and the accompanying differences in church hierarchy reflect this difference in beliefs.

Typically, protestant churches have three ranks of ordained leadership; pastors, who are required to be seminary graduates, are ordained by the central authority of the denomination, while the elders and deacons are ordained by the gathered congregation. Women and men are equally qualified for all positions, including pastor, in nearly all, if not all, protestant denonimations. Protestant pastors, elders, and deacons are all permitted to marry.

- Biskop Erik Norman Svendsen.jpg

Protestant: Bishop Erik Norman Svendsen of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Denmark.

The Buddhist monastic order

Just as Christian holy orders can trace their roots to the Apostles of Jesus, the holy orders in Buddhism connect back to the central roots of Buddhism, the original followers of Buddha. When Prince Siddharta chose to follow the ascetic path to find the truth, giving up his worldly position, and became Buddha, he set up a community of monks, Bikkhu sangha (sanskrit - Bhiksu) and nuns, Bikkhuni sangha, to help with the work of teaching the Dharma (Buddhist teachings). Bhiksu may be literally translated as "beggar" or more broadly as "one who lives by alms". The original rules and regulations of the monastic orders, called the patimokkha, were set out by the Buddha himself, then adapted over time to keep step with changes in the world. Their lifestyle is shaped so as to support their spiritual practice, to live a simple and meditative life, and attain Nirvana, the goal of all Buddhists.

The establishment of a monastic community meant that the greater community of Buddhist faithful could be described in four groups: male and female lay believers, and Bikku (Bhikkhu in pali and Bhikshu in Sanskrit), and Bikkhuni (Bhikkuni in Pali and Bhikshuni in Sanskrit), the male and female ordained monks. Joining the ranks of the ordained is the highest goal of Buddhist practitioners. The monks and nuns are the pillars of the community of faith, spreading Buddhist teachings and serving as living examples for the lay believers to follow. Also, by serving as a field of merit, they give laymen the opportunity to gain merit by supporting the ordained community with donations of food and money. The disciplined life in the monastic order also contributes towards the monks' and nuns' pursuit of the liberation of Nirvana through the cycle of rebirth.

Monks usually traveled in small groups, living at the outskirts of the village. The monks depended on donations of food and clothing from the residents of the village. Part of Buddha's direction was that the members of the monastic order gather in larger groups and live together during the rainy season. The dwellings where they stayed during these times were also to be given voluntarily by people from the community. Over time, the dwellings became more permanent, the monks settled in reagions; their lifestyle became less nomadic, and the monks started to live communally in monasteries. The patimokka, rules governing life in the monastery, were developed, prescribing in great detail the way to live and relate in a community. For example, the patimokka in the Theravada branch of Buddhism contains 227 rules.

Joining the order

Laymen who wish to join the order must approach a monk who has been in the order for at least ten years, and ask to be taken in. First ordained as a samanera (novice), they have their heads shaved, and begin to wear the robes appropriate to the order they have joined. For a period of at least a year, they must live by the Ten Precepts - refraining from sexual contact, refraining from harming or taking life, refraining from taking what is not given, refraining from false speech, refraining from the use of intoxicant, refraining from taking food after midday, refraining from singing, dancing, and other kind of entertainment, refraining from the use of perfume, garland and other adornments, refraining from using luxurious seat and refraining from accepting and holding money. They are not required to live by the full set of monastic rules. Boys from eight years old can be ordained as samanera. Women are usually first ordained when adults. From the age of 20, samanera can be ordained to the full level of Bikkhu or Bikkhuni.

The Buddha instructed that in order to be ordained as Bikkhu or Bikkhuni, the applicant need to have a preceptor. The preceptor is usually the elderly monk that ordained the applicant as samanera. The samanera needs to approach a community of at least ten monks of at least ten years standing each and who are well respected for their virtues and learning. The monks would then ask the applicant eleven questions to assess his readiness, suitability and motives: (1) Are you free from disease? (2) Are you a human being? (3) Are you a man? (4) Are you a free man? (5) Are you free from debt? (6) Do you have any obligations to the king? (7) Do you have your parents' permission? (8) Are you at least twenty years of age? (9) Do you have your bowl and robe? (10) What is your name? (11) What is your teacher's name? If the applicant answers satisfactorily to these questions, he/she will request ordination three times and if there is no objection from the assembly, he/she is considered a monk/nun.

Monks and nuns take their vows for a lifetime, but they can "give them back" (up to three times in one life), a possibility which is actually used by many people. In this way, Buddhism keeps the vows "clean". It is possible to keep them or to leave this lifestyle, but it is considered extremely negative to break these vows.

Unlike Chrisian holy orders, which define three distinct hierarchical ranks in the major orders, in Buddhism, there are not formal rules that define a hierarchy within the monastery. However, tacit rules of obedience to the most senior member of the Sangha, and other rules stemming from the teacher/student, senior/junior and preceptor/trainee relationship are at work within the monastery. Decisions to be taken concerning life in the monastery are usually done in communal meetings.

The daily running of the monastery is in the hand of an abbess or abbot who may appoint assistants. The position of abbess / abbot are usually held by one among the senior members of the monastery. In some case he/she will be elected by the members of the order, and in other cases the lay community will choose him/her.

Women were not originally included in the ascetic community by the Buddha. However, after incessant pressures from his aunt and stepmother, Maha Pajapati Gotami, he accepted the ordination of women. Stronger restrictions and rules were put on the communities of nuns, however, such as the precedence of monks over the nuns in matter of respect and deference, the prohibition of nun teaching monks, and that the confession and punishment of nuns should be done before a joint assembly of both nuns and monks.

Robes The special dress of ordained Buddhist monks and nuns, the robes, comes from the idea of wearing cheap clothes just to protect the body from weather and climate. They shall not be made from one piece of cloth, but mended together from several pieces. Since dark red was the cheapest colour in Kashmir, the Tibetan tradition has red robes. In the south, yellow played the same role, though the color of saffron also had cultural associations in India; in East Asia, robes are yellow, grey or black.

Marriage and celibacy

Celibacy was a requirement for the members of the Buddhist orders, as established by Buddha. Even up until today, in some branch of Buddhism this rule is still in effect. However, as the Buddha was a pragmatic teacher and the rules he set for the monastic life prone to change, he predicted, as women were ordained that the rule of celibacy will not hold for more than 500 years. In fact, since the 7th century in India, some groups of monks were getting married. In Japan, from the Heian period (794-1105 C.E.), cases of monks getting married started to appear. However it was during the Meiji restoration, from the 1860's that marriage by monks was officially encouraged by the government. Since that time, Japan remains the country with the largest number married monks among the higher orders. Marriage by monks is also practiced in other country, including Korea and in Tibet.

Tantric vows A lay person (or a monk/nun) engaging in high tantric practices and achieving a certain level of realization will be called a yogi (female "yogini", in Tibetan naljorpa/naljorma <rnal hbyor pa/ma>). The yogis (monks or lay) observe another set of vows, the tantric vows (together with the bodhisattva vows); therefore, a yogi/yogini may also dress in a special way, so that they are sometimes called the "white sangha" (due to their often white or red/white clothes). Both ways, tantric and monastic are not mutually exclusive; although they emphasize different areas of Buddhist practice, both are ascetic.

Other vows There are still other methods of taking vows in Buddhism. Most importantly, "Bodhisattva vows" are to be taken by all followers of Mahayana Buddhism; these vows develop an altruistic attitude. Another "centering of self" method is taking strict one-day vows which are somewhat similar to monk's/nun's vows ("Mahayana precepts"), but last only from one sunrise to another sunrise.

Conclusion

"Ordination" in Buddhism is a cluster of methods of self-discipline according to the needs, possibilities and capabilities of individuals. According to the spiritual development of his followers, the Buddha gave different levels of vows. The most advanced method is the state of a bikshu(ni), a fully ordained follower of the Buddha's teachings. The goal of the bhikku(ni) in all traditions is to achieve liberation from suffering.

Beside that, the Mahayanist approach requires bodhisattva vows, and the tantric method requires tantric vows. Since some people are not attracted to monk/nun ordination, all other vows can be taken separately. On the other hand, it is said that one cannot achieve the goal without taking the vows of individual liberation—i.e., comply with the ethical disciple inscribed in these vows.

- Monk and lanterns.jpg

Monk and Lanterns, Bongeunsa Temple, Korea.

- Beijingmonk.jpg

Chinese monk lighting incense in Beijing temple.

- Buddhist monk.PNG

A Buddhist monk.

- Australian Buddhist monk.PNG

An Australian Buddhist monk.

The Caliphate: Muslim holy orders

In Islam, similar to Christianity and Buddhism, the lineage of holy orders leads back to the beginning of the Muslim faith, the direct disciples of the prophet Muhammad. Islam is a religious institution and also the source of institutions that govern and rule many aspects of the social life within the Islamic community (the ummah). At the death of the prophet Muhammad (632 C.E.), a group of Muslim at Medina convened to nominate his successor. The gathering was organized in the hut of Aisha, the favorite wife of the prophet, while the preparations were being made for his burial. The Father of Aisha, Abu Bakr, was chosen as the khalīfah(caliph) or successor of the prophet. As caliph, Abu Bakr was considered the political and administrative successor of the prophet. It is from the second caliph, Umar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb that the title came to be associated with spiritual authority.

However, not everyone agreed on the choice of Abu Bakr. A faction claimed that the rightful successor of the prophet should be Alī, Muhammad's son-in-law, the husband of Fatimah. The bitterness and conflict between Ali/Fatima and Abu Bakr/Aisha and their respective supporters would lead to the major schism in Islam: the Sunnite faction, whose members abide by the choice of Abu Bakr and the Shiite Muslims who are supporters of Ali.

The Sunnis assert that the caliph should be from the tribe of the prophet Muhammad, the Quraish. Abu Bakr was also from that same tribe. However, in the interest of practicality, that requirement has been loosened at times, as many rulers were accepted as caliph even though they were decidedly not from the Quraish tribe. Nonetheless the fact that they were creating a conducive environment for the practice of the Islamic faith and were active participant in the spreading and protection of the ummah was a base for the legitimacy of their caliph title. There were three ways that caliphs were chosen in the Sunnite community. The early caliphs were elected by a shura, or council of the elders of the community, as this was the traditional way the of chieftain delegation in the Quraish tribe. However, after a time, hereditary appropriation of the title began to overshadow the democratic process, leading to the rise of dynasties. In later centuries, accession to the head of the caliphate was sometimes accomplished by military force.

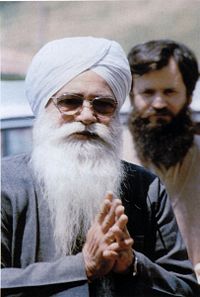

In theory, adherants of the Sunni Muslim faith approach Allah directly because the religion includes no intercession of saints, no officially designated holy orders or organized clerical hierarchy, and no true liturgy. In practice, however, there are duly appointed religious figures, some of whom exert considerable social and political power. Among them are men of importance in their community who lead prayers and give sermons at Friday services. Although in the larger mosques the imams are generally well-educated men who are informed about political and social affairs, an imam need not have any formal training. Among beduin, for example, any literate member of the tribe may read prayers from the Quran. Committees of socially prominent worshipers usually run the major mosques and administer mosque-owned land and gifts.

In the Shiite realm, the caliph may also be referred to as Imam. In contrast to the Sunnis, Shiites believe that the caliph, being a direct descendant of the prophet, is divinely appointed and preserved from sin. Moreover, he has absolute spiritual authority and the power to determine matters of doctrinal importance.

Caliphs had temporal and spiritual power over the Muslim community; other offices were created to help them in the execution of their duties. States which were part of the caliphate were called Emirate or Sultanate headed by emir or sultan. These were usually appointed. However at times emirs and sultans seized power, or conquered states by force, and then came to the caliph to seek recognition, which the caliph often could not refuse. To help them handle both religious and legal matters, the caliphs surrounded themselves with renowned scholars and Islamic lawyers.

Titles used for Islamic leaders

Each Muslim community is independent, and the title of the cleric at the head of the community varies with the size, location and custom of the group. The network of supporting clerics is also different from community to community. Following is a list of the titles most frequently used for the spiritual and/or political heads of Muslim communities and the clerics who support the head of the community in various capacities.

Caliph Caliph is the term or title for the Islamic leader of the Ummah, or community of Islam. It is an Anglicized/Latinized version of the Arabic word خليفة or Khalīfah, which means "successor", that is, successor to the prophet Muhammad. Some Orientalists wrote the title as Khalîf. The Caliph has often been referred to as Ameer al-Mumineen (أمير المؤمنين), or "Prince of the Faithful," where "Prince" is used in the context of "commander." The title has been defunct since the abolition of the Ottoman Sultanate in 1924. Historically selected by committee, the holder of this title claims temporal and spiritual authority over all Muslims, but is not regarded as a possessor of a prophetic mission, as Muhammad is regarded in Islam as the last prophet.

Imam Imam is an Arabic word meaning "Leader". The ruler of a country might be called the Imam, for example. The term, however, has important connotations in the Islamic tradition especially in Shia Beliefs . In Sunni belief, the term is used for the founding scholars of the four Sunni madhhabs, or schools of religious jurisprudence.

Ayatollah Ayatollah (Arabic: آية الله; Persian: آیتالله) is a high title given to major Shia clergymen. The word means 'sign of God', and those who carry the title are experts in Islamic studies such as jurisprudence, ethics, philosophy and mysticism, and usually teach in schools (hawza) of Islamic sciences. Ayatollahs can reach the position of an Marja-e-Taqlid, which allows them to issue fatāwa (plural of "fatwa"). Also see Grand Ayatollah.

Mullah Mullah are Islamic clergy who have studied the Qur'an and the Hadith and are considered experts on related religious matters in this religion. The term Mullah is a variation of the word mawla and is used mainly in Central Asia and in the Sub-Continent .

Mujtahid Mujtahid An interpreter of the Islamic scriptures, the Qur'an and Hadith. These were traditionally Muftis, who used interpretation (Arabic ijtihad) to clarify Islamic law; but in many modern secular contexts. In that case, the traditional Mufti may well be replaced by a university or madrasa professor who informally functions as advisor to the local Muslim community in religious matters such as inheritance, divorce, etc.

Muezzin Muezzin (the word is pronounced this way Turkish, Urdu, etc.; in Arabic: مؤذن [IPA: mʊʔæðːın) is any person at the mosque who makes the adhan (call to prayer) to Friday service and the five daily prayers, or Salah. Some mosques have specific places for the adhan to be made from, such as a minaret or a designated area in the mosque.

Sahib Sahib is a denoting an Islamic leader held in high regard by one or more other Muslims. The term is used almost exclusively in the north African sub-continent area. The term is Arabic in origin and can be translated as lord, master, or friend.

- Imam Shamil.jpg

Imam_Shamil (1797 - 1871), political and religious leader of the Muslim tribes of the Northern Caucasus.

- Imam Khomeini 38.jpg

Imam Khomeini, first and only Iranian cleric to be addressed as Imam

- Ali Gomaa.JPG

Ali Gomaa, Grand Mufti of Egypt

- Ayatollah Dr. Mahdi Hadavi.JPG

Ayatollah Dr. Mahdi Hadavi, Iran

- Kazem Shariatmadari.jpg

Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari (1905 – 1986), a senior Shi'a cleric

Judaism: From the priest to the rabbi

Jewish leadership has evolved over time. In the Jewish tradition, the history of holy orders begins from the time of the twelve tribes of Israel, from some time before 1000 B.C.E., with the priests and other leaders coming from the tribe of Levi, starting with two members of this tribe, Moses and his elder brother, Aaron. Since the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 C.E., there has been no single body that has a leadership position over the entire Jewish diaspora. Various branches of Judaism, as well as Jewish religious or secular communities and political movements around the world elect or appoint their governing bodies, often subdivided by country or region.

Mosaic period

Jewish society during the time of Moses was headed by the members of the Levite tribe, in both the political and religious aspects. Moses was the political leader, prophet and messenger. He was the only one having direct communication with the God of Israel. Aaron was in the position of the priest and direct assistant to Moses. The other members of the Levite tribe were spiritual assistants and aides in keeping the faith of the God of Israel.

As the political and spiritual leader of the Hebrews, Moses received a revelation from Yahweh (God) transmitting the Ten Commandments that became the fundamental law of the Hebrews. Moses is also credited as the author of the five first books of the Tanakh (Jewish Bible), known as the Pentateuque and the written Torah. Following the instruction of Yahweh, he also directed the Hebrews in construction the Mishkan, or Tabernacle, to serve as the dwelling place of God among the community, and the Ark of the Covenant, which contained holy articles symbolizing the covenant between Yahweh and the Hebrew people.

Aaron is revered as the head of the Jewish priesthood. He took a decisive part in the exodus of the Hebrews from Egypt. He was instructed to act as “the mouth” of Moses in front of the Egyptian Pharaoh and his court. He is the one who asked pharaoh to liberate the people of Israel and who used his rod to show the might of Yahweh, the God of Israel. Yahweh would later order Moses to call upon Aaron and his sons to anoint and consecrate them to be perpetual priests. As priests they were the one to intercede for the people of Israel and to perform the sacrificial rites. Aaron is thus viewed in the Jewish tradition as the founder and head of the Jewish priesthood. Aaron was also given the unique privilege of bringing offerings on Yum Kippur (the Day of Atonement) once a year, to the holiest part of the tabernacle, the Holy of Holies.

Period of the temple

Before his death, Moses appointed Joshua as his successor. However, after Joshua, and from the time the Hebrews settled in the promised land of Canaan, the position of political leader and prophet/Messenger of God was occupied by self acclaimed charismatic leaders who came to be known as the judges. The functions of political and religious leadership were later split starting with the anointment of King Saul. Starting with Saul, the king was the military and political leader of Israel while the roles of prophet and messenger of God were fulfilled by prophets, who acted as spiritual advisors to the king and the people of Israel, receiving messages through visions and dreams, and transmitting them to the people of Israel and the king.

After a time of nomadic living and exile, the tribes of Israel settled down in Canaan, and the city of Jerusalem was established as the political and religious center of the twelve tribes. During the reign of King Solomon, the first temple was constructed in Jerusalem. The priests were the people in charge of officiating ceremony and performing the sacrificial rites. They operated in sanctuaries and altars all throughout Israel. After the construction of the Temple in Jerusalem as the center of worship in Israel, the priest in charge of the temple was elevated to the rank of High priest, and was the leader of all the other priests. Lower ranking priests assisted in managing the finances and administration of the temple. The first high priest was Zadok, from the House of Eleazar, son of Aaron. The succeeding high priests came from the house of Zadok. Other religious administrators and officials came from other branches of the tribe of Levi.

However, the priesthood was under the control of politicians, who held the right to appoint the priests and sometimes removed them from office, going against the rule that the priesthood is a perpetual office. When Israel came under the control of foreign political powers, with the demise of the Hebrew kingdom, the power within Israel shifted, and from that time the High priest and priests became the center of both the spiritual and political life of the Hebrew community. This situation continued under a variety of political conditions until the second destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem in 70 C.E. Without the Temple of Jerusalem, the Priesthood was deprived of its seat of power, and disappeared.

Hebrew scholars, called Rabbis, took over the leadership of the Hebrew people, and Judaism underwent changes to adapt to the political situation that they found themselves in, without a sovereign and without a political capital, unable to continue the rites and sacrifices of their traditional faith. The Rabbinic Judaism that developed from the first century destruction of the temple continues until today.

Rabbinic Judaism

70 C.E. to the 1600's

Rabbinic Judaism takes its origin from the work of the Pharisaic Rabbis. The Pharisees were a religious party within Judaism that flourished between 515 B.C.E. and AD 70. They were laymen and scribes who believed that God gave two kind of law to Moses, the written law found in the Torah, and the oral law stemming from the words of the prophet and other Jewish oral traditions. The meaning and interpretation of the laws are mutable based on the contemporary circumstances and conditions and on reason. Men should use their reason to apply and interpret the Torah and the oral tradition to solve contemporary problems.

The Pharisees had long arguments with the priests and their religious party, the Sadducees. To the Pharisee, worship consist in the study of scripture, prayer and work of piety, not in the bloody sacrifices offered in the Temple by the priest. They thus promoted and developed the synagogue, religious center focused on worship and study of the torah, rather than sacrifices. With the destruction of the temple, when it became difficult for the priests to continue in performing their sacrifices, Rabbinic Judaism came into prominence and the synagogue replaced the temple as the place of worship. For nearly two thousand years after the destruction of the Second Temple, without a the Jewish people were scattered into exile throughout the world, and turned to their most learned rabbis for local leadership and council. During this time the original work of the Mishnah which became the "de-facto constitution" of the world's Jewry. The final editions of the Talmud became the core curriculum of the majority of Jews.

1700's to 1800's

The loose collection of learned rabbis that governed the dispersed Jewish community held sway for a long time. Great parts of Central Europe accepted the leadership of the rabbinical Council of Four Lands from the 1500s to the late 1700s. In [Eastern Europe]], in spite of the rivalry between schools of thought, rabbis were regarded as the final arbiters of community decisions. Tens of thousands of Responsa and many works were published and studied wherever Jews lived in organized communities.

Modern religious leadership (after 1800s)

Decline of rabbinical influence

With the growth of the Renaissance and the development of the secular modern world, and as Jews were welcomed into non-Jewish society particularly during the times of Napoleon in the 1700s and 1800s, Jews began to leave the Jewish ghettos in Europe, and simultaneously rejected the traditional roles of the rabbis as communal and religious leaders. New leaders such as Israel Jacobson, father of the German Reform Judaism movement, launched an egalitarian, modernist stance that challenged the Orthodoxy. The resulting fractures in Jewish society has translated into a situation whereby there is no single religious governing body for the entire Jewish community at the present time.

Modern Synagogue leadership

In individual religious congregations or synagogues, the spiritual leader is generally the rabbi. Rabbis are expected to be learned in both the Talmud and the Shulkhan Arukh (Code of Jewish Law) as well as many other classical texts of Jewish scholarship. Rabbis go through formal training in Rabbinical texts and responsa, either at a yeshiva or similar institution. "Rabbi" is not a universal term however, as many Sephardic rabbinic Jewish communities refer to their leaders as hakham ("wise man"). Among Yemenite Jews, known as Teimanim, the term mori ("my teacher") is used. Each religious tradition has its own qualifications for rabbis. In addition to the rabbi, most synagogues have a hazzan (cantor) who leads many parts of the prayer service. A Gabbai may fill a position similar to "sexton."

Views under Rabbinic Judaism regarding hereditary holy orders

Among Rabbinic Judaism arose different forms of contemporary Judaism, including Orthodox Judaism, Conservative Judaism, Reform Judaism, and Reconstructionist Judaism. These different branches hold differing views concerning the Kohanim (descendants of Aaron) and the other branches of the Levite tribe.

Orthodox Judaism

Those who adhere to the Orthodox view of Judaism believe that the priesthood will resume its activities at the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem. The Levites and Kohanim should therefore stand in readiness and keep their sanctity according to the prescriptions found in the Torah. The Kohanim are given privileges and precedence in religious matters over the other members of the Jewish community (the Yisroel). Kohanin are also bound to follow prescriptions and laws about purity and marriage stemming from the Torah and the Talmud.

Conservative Judaism

To the Conservative, even if the temple were to be rebuilt, the sacrificial rites are not to be restored. Hence, the Kohanim, even though have to keep their purity as ascribed in the Torah are given more freedom, especially in the realm of marriage.

Reform and Reconstructionist Judaism

To adherants of Reform and Reconstructionist Judaism, the sacrificial rites are no longer necessary and are incompatible with modern time. Moreover, the division of the Hebrew people into social ranks based on heredity is viewed as an unegalitarian practice that should be abolished. Therefore, Reform and Reconstructionist Judaism give no recognition of any special status for the Kohanim.

Orthodox and Haredi rabbinic leadership

In Israel the office of Chief Rabbi has always been very influential. Various Orthodox movements, such as Agudath Israel of America and the Shas party in Israel strictly follow the rulings of their Rosh yeshivas who are often famous Talmud scholars. The last Rebbe of Lubavitch, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the late Rabbi Elazar Menachem Shach, and Rabbi Ovadia Yosef in Israel are examples of powerful contemporary Haredi rabbis. The Haredi Agudah movements receive and follow the policy guidelines of their own Council of Torah Sages. In the Hassidic movements, leadership is usually hereditary.

Reform, Progressive, Liberal, Conservative, and Reconstructionist leadership

In both the Reform and Conservativeof Judaism, rabbis are often trained at religious universities, such as the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York City for the Conservative movement, Hebrew Union College for the American Reform movement, and Leo Baeck College for the UK Liberal and Reform Movements. The Reform, Conservative, and Reconstructionist traditions each have their own governing group or individual leaders. Membership in these governing groups are selected by representatives of the Jewish community they serve, with Jewish scholarship considered to be the key factors for determining leaders. These governing bodies make decisions on the nature of religious practice within their tradition, as well as ordaining and assigning rabbis and other religious leaders.

The body of Conservative rabbis is the Rabbinical Assembly, which maintains a Committee on Jewish Law and Standards. The body of Reform rabbis is the Central Conference of American Rabbis.

- Reb Moshe Feinstein.jpg

- Baba Baruch.jpg

- Eliyahu2.jpg

- Ellon.jpg

- Shlomo Goren.jpg

- Chernobil rabbis.jpg

- Jewish Canadian soldiers during WWII.jpg

- Yisroel Dovid Weiss.jpg

- Israel-Western Wall.jpg

Rabbis studying at the Wailing Wall, the place where Jews come to mourn the destruction of the Holy Temple, and pray for its reconstruction.

The caste system and Hinduism

Hinduism is an umbrella term for various religious traditions practiced in India. It is based on an ancient religion, the Veda. The Veda was brought in India along with the invasion of the Aryans in the North West part of India around 1500 B.C.E. To understanding the current holy order in Hinduism, it is helpful to understand the origins of Hinduism and its most ancient text, the Vedas. Aryan society, who brought the Vedas, was divided into a hierarchy made up of priests, warriors and commoners. That social stratification was adapted as they conquered new lands and more population were integrated into their society. The Rigveda recorded an ancient tradition of socioeconomic categories called varnas (colours). When the Aryans first encountered the dark-skinned people of North western India they called called them daha (enemy) or darsa( servant), and the people of these tribes came to occupy a new class of servant in the Aryan society.

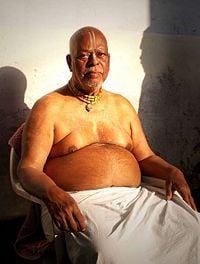

Hymn 10.9 of the Rigveda, states that humanity emerged in the form of four varna from the self sacrificial rite of Purusha (the primal man). From the mouth of Purusha was made the Brahmans, from his arms was made the Rajanyas (later renamed Kshatriva), from his two thighs was made the Vaishyas and from his feet were born the Shudras. Member of the brahmins, rajanis and Vaishyanis group constituted the upper varnas and the Aryan invader were the members of these varnas. The darsa were members of the shudras, the lowest lower varna. Brahmans were the priests and religious officials. They were the teachers of the veda, the sacred knowledge. The kshatriva were composed of rulers and warriors and the vaishva was composed of farmers, merchants, traders and craftmen. By virtue of their Aryan descent, the members of the upper varna can reach the status of dvija (twice born). The term twice born refers to the fact that the males of these varnas pass through the upanayana, a ceremony to enter into Aryan adulthood, when they reach 12 years of age. Upon completion of that ceremony, the young boy is considered fit to receive sacred knowledge and participate in specified sacraments. He is reborn as a Hindu.

The members of the shrudra varna, since they were not from Aryan descent did not participate in the ceremony of rebirth. Furthermore, they were not allowed to participate in the Vedic rites with the upper cast and did not have the privilege to study and read the Veda. They had their own priests and religious rites.

When the Aryans expanded their conquest further into India, they met new communities. To accommodate the social structure of their society, another stratum was added, below the shudra, the untouchables. The members of the untouchables perform tasks considered dirty by the rest of society, such as latrine cleaner. Because of their high level of “impurity” they were segregated in hamlets outside the town or village boundary. They were forbidden entry to many temples, schools and wells from which the higher castes drew water. These practices continue even today, especially in rural areas.

It is believed by some scholars that membership in a varna was primarily based on ones occupation. It is however customarily accepted in Indian society that membership in a varna is primarily through birth, thus the existence of the notion of jati or caste. Hence, varna has slowly become synonym with caste.

The relationship between the members of casts is highly regulated around the notion of purity and impurity. The higher castes are considered more pure and strive to maintain their purity. The lower casts are considered as source of impurity. For one to alter his/her purity level is mainly through four medium: marriage, drink, food and touch. For a member of a higher caste who was contaminated with the impurity of a lower cast to gain back his/her status, he has to pass through rite of purification.

Social mobility within the varna is not theoretically possible during ones lifetime. For a lower varna to move up the ladder, he should be a devoted and good member of the varna and wait to be reborn after death in a higher varna. However some individuals succeeded in integration a higher varna during their lifetime.

They succeed mainly through emulating the higher cast and taking their habits of conduct. When this is combined with some form of power over the higher cast, the mobility is more easily accomplished. An untouchable for example, to emulate the Shudra will take on the Shudra dressing and dietetic code. He will also strive to avoid performing work the Sudra see as impure. All these effort will be deem successful if for example, the Shudra agree to eat a meal cooked by him.

This kind of mobility is usually between two closely ranked casts. An untouchable will hardly seek to rise from is level to the level of Brahman. It is this process of raising up to the varna ladder and being accepted by the higher caste that was one of the main factors in the spread of Hinduism among the population of south western Asia.

The caste system, even though it is viewed as a fundamental ingredient of Indian society is criticized by many Hindu scholars who are seeking for its adaptation to modern time. The untouchables, who are the lowest caste because of the burden put upon them by the varna system, usually seek refuge in religions were there is no legal caste system. Hence the easy conversion of those from this low caste to Buddhism, Christianity and Islam. The notion of untouchability was declared illegal in the constitution of India of 1949 and that of Pakistan in 1953. However, the varna system is still strong in rural areas and many of the untouchables are still struggling to improve their civil right and recognition.

Sannyasa, the final stage of the varna system

Sannyasa, (Devanagari: संन्यास) sannyāsa is the renounced order of life within Hinduism. It is considered the topmost and final stage of the varna and ashram systems and is traditionally taken by men at or beyond the age of fifty years old or by young monks who wish to dedicate their entire life towards spiritual pursuits. One within the sannyasa order is known as a sannyasi or sannyasin.

Etymology

Saṃnyāsa in Sanskrit means "renunciation", "abandonment". It is a tripartite compound of saṃ- has "collective" meaning, ni- means "down" and āsa is from the root as, meaning "to throw" or "to put", so a literal translation would be "laying it all down". In dravidian languages, "sanyasi" is pronounced as "sannasi".

Danda as spiritual attribute

In the Varnashrama System or Dharma of Sanatana Dharma, the 'danda', a holy staff, (Sanskrit; Devanagari: दंड, lit. stick) is a spiritual attribute and axis mundi of certain deities such as Bṛhaspati, and holy people such as sadhu carry the danda as an austerity and marker of their station as a mendicant renunciate or sannyasin.

Categories of sannyasi

There are a number of types of sannyasi in accordance with socio-religious context. Traditionally there were four types[1] with different stages of dedication. In recent times, sannyasi are more likely to be divided into two distinct orders: "ekadanda" (literally single stick) and "tridanda' (triple rod or stick) monks.[2] The former are part of the Sankaracarya tradition[3], and the second is the sannyasa discipline followed by various vaishnava traditions and introduced to the west by followers of the reformer Siddhanta Sarasvati. The two orders each have their own traditions of austerities, attributes, and expectations.

Lifestyle and goals

The sannyasi lives a celibate life without possessions, practises yoga meditation — or in other traditions, bhakti, or devotional meditation, with prayers to their chosen deity or God. The goal of the Hindu Sannsyasin is moksha (liberation), the conception of which also varies. For the devotion oriented traditions, liberation consists of union with the Divine, while for Yoga oriented traditions, liberation is the experience of the highest samadhi (enlightenment). For the Advaita tradition, liberation is the removal of all ignorance and realising oneself as one with the Supreme Brahman. Of the 108 Upanishads of the Muktika, 23 are considered Sannyasa Upanishads.[4]

Within the Bhagavad Gita, sannyasa is described by Krishna as follows:

"The giving up of activities that are based on material desire is what great learned men call the renounced order of life [sannyasa]. And giving up the results of all activities is what the wise call renunciation [tyaga]." (18.2)[5]

The term is generally used to denote a particular phase of life. In this phase of life, the person develops vairāgya, or a state of determination and detachment from material life. He renounces all worldly thoughts and desires, and spends the rest of his life in spiritual contemplation. It is the last in the four phases of a man, namely, brahmacharya, grihastha, vanaprastha, and finally sannyasa, as prescribed by Manusmriti for the Dwija castes, in the Hindu system of life. However, these four stages are not necessarily sequential, but on the other hand can not be reversed, in other sense they are progressive phases, one can skip one, two or three ashrams, but can never revert back to an earlier ashrama or phase. Various Hindu traditions allow for a man to renounce the material world from any of the first three stages of life.

Monasticism

Unlike monks in the Western world, whose lives are regulated by a monastery or an abbey and its rules, some Hindu sannyasin are loners and wanderers (parivrājaka). Hindu monasteries (mathas) never have a huge number of monks living under one roof. The monasteries exist primarily for educational purposes and have become centers of pilgrimage for the lay population. Ordination into any Hindu monastic order is purely at the discretion of the individual guru, or teacher, who should himself be an ordained sannyasi within that order. Most traditional Hindu orders do not have women sannyasis, but this situation is undergoing changes in recent times.

- Priest offers Flowers to the goddess Saraswati.JPG

- Ganga idol.jpg

- Guru Har Rai.jpg

- Dictation of the Guru Granth Saheb.jpg

- Ravidaskijai.JPG

- Hindu priest altar.jpg

- Brahman priest speaking.jpg

Daoist cleric orders

Daoism is a collection of religious practices with ancient Chinese roots estimated to go back as early as 500 B.C.E. or farther. The development of Daoism was influenced by the teaching of Laozi (dates unknown) and Zhuangzi (4th c. BCE), but they are not considered founders of Daoism. The absence of a single specific starting event or teacher means that the holy orders in Daoism do not eminate from a single historical source; nevertheless, Daoist Priests are viewed with a great deal of respect and authority, and new priests can only attain their status through them.

Training to become a Daoist priest begins with choosing a Daoist master (priest) and begin training in the Daoist scriptures and commandments, which are traditionally transmited orally from Master to student. After a period of study, the master will decide whether the young adept has a character appropriate to begin registration and continue study on the path to what the Daoists call Complete Perfection, and if he is qualified, he may become a formal disciple, and begins study toward qualification to be added to the formal Register. After the long study and practice required to reach complete perfection, a process that may require as many as 120 different areas of mastery, the disciple will be added to the Register of the sect under which he has been studying. To attain higher recognition and authority within the Dao community, he must then study further, and be granted registration in other sects, beyond his own.

Daoist priests serve in the temples, guiding lay Daoists and novices, and leading the rites and practices of Daoism in the temples. These include morning and evening rites, which involve incantations, readings of scriptures, as well as fasting and the practice of Refining the Vital Breath, accomplished through special Daoist gymnastics. Some Daoist clerics devote time to Daoist music, which is meant to enhance meditation.

- Spanish Taoist priests.PNG

- Taoist ritual.PNG

- Taoist priests officiating rites (0).PNG

- Taoist priestesses playing music.PNG

- Taoist priests concert.PNG

Shinto priests

Shinto is a ancient set of customs, rites and practices of Japan with origins going back thousands of years. Sometimes described as a religion, and sometimes simply as a way of life, Shinto rites and ceremonies touch almost every aspect of Japanese life. Prayers, rites and ceremonies are carried out at public and private shrines, sometimes alone, or with family members, and sometimes in the company of a Shinto Priest.

Becoming a Shinto priest

To become a Shinto priest, it is necessary to pass the certification test administered by the Association of Shinto Shrines. The most common way to prepare for the test is to attend a training course, either a post-secondary course in the Shinto departments Kōgakkan University or Kokugakuin University, or a shorter one and two year programs, available for candidates who have already attended college and need only the specialized Shinto courses. It is also possible to take a shorter course or study privately; the primary requirement is passing the certification test.[6]

- Shinto priests marching.jpg

- Shinto priest.jpg

- Shinto priest with tea.jpg

- Shinto wedding procession.jpg

Summary

Various religious traditions have leaders that are members of holy orders. They perform a wide variety of functions in their religious communities, including leading worship, teaching scriptures, guiding prayers, ministering to the poor, the sick, the troubled, organizing community services of many kinds, and many other types of service. In some religious societies, attaining holy orders also brings with it duties of political, military or social leadership in addition to religious leadership.

All varieties of holy orders gain their authority from long revered and respected traditions and lineages of earlier leaders. Care is taken to make sure new members of the order are qualified and adequately trained to equip them for religious leadership and service. In addition, members of holy orders are called upon to teach by example, to show an exemplary way of life that other adherants can watch and learn from. In their teaching, their guidiance, their religous leadership and by their examples, members of holy orders hold the ability to exert a great amount of influence on the lives of those in their communities, and on the relationships between them, and between their community and other communities. In this way, they hold the power to greatly influence the future course of world history.

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Campbell, Dennis M. The yoke of obedience: the meaning of ordination in Methodism. United Methodist studies. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1988. ISBN 9780687466603

- Inwood, Kristiaan. Bhikkhu: Disciple of the Buddha. Bangkok: Thai Watana Panich, 1981. (No ISBN listed in the Library of Congress catalog.)

- Oden, Thomas C. Pastoral theology: essentials of ministry. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1983. ISBN 9780060663537

- Willimon, William H. Calling & character: virtues of the ordained life. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2000. ISBN 9780687090334

- Willimon, William H. Pastor: the theology and practice of ordained ministry. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2002. ISBN 9780687045327

External links

- Old Catholic Vocations Website. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- Priesthood - Catholic Sacrament of Holy Orders - Ordination. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- Vatican II Council. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Holy_Orders history

- Bhikkhu history

- Islamic_religious_leaders history

- Islam_in_Syria history

- Jewish_leadership history

- Sannyasa history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ The Samnyasa Upanisads: Hindu Scriptures on Asceticism and Renunciation, Patrick Olivelle, Oxford University Press, 1992

- ↑ Srimad Bhagavatam 1.3.30 First Canto By A. C. Bhaktivedanta Prabhupada, Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, ISBN 0912776285

- ↑ Srimad Bhagavatam: Fourth Canto By A. C. Bhaktivedanta Prabhupada, Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, ISBN 0912776382

- ↑ Patrick Olivelle, Oxford University Press, 1992

- ↑ Bhagavad Gita 18.2

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Shinto, Establishment of a National Learning Institute for the Dissemination of Research on Shinto and Japanese Culture, April 13, 2006, Kokugakuin University. Retrieved September 7, 2008.