Difference between revisions of "Harvard University" - New World Encyclopedia

(Started) |

|||

| (52 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | + | {{Ebcompleted}}[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] |

[[Category:Education]] | [[Category:Education]] | ||

| − | {{ | + | [[Category:Universities and Colleges]] |

| + | {{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}}{{2Copyedited}} | ||

{{Infobox_University-Jen | {{Infobox_University-Jen | ||

|name = Harvard University | |name = Harvard University | ||

| − | |image = [[Image:Harvard | + | |image = [[Image:The Lowell House (Harvard University).jpg|200 px| Dunster Tower, Harvard]] |

| − | |motto = Veritas | + | |motto = Veritas ''(Truth)'' |

| − | |established = September 8, 1636 (OS), September 18, 1636 (NS) | + | |established = September 8, 1636 (OS), September 18, 1636 (NS) |

| − | |type = | + | |type = Private |

| − | + | |city = [[Cambridge, Massachusetts|Cambridge]] | |

| − | + | |state = [[Massachusetts|Mass.]] | |

| − | + | |country = [[United States|U.S.]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |city | ||

| − | |state | ||

| − | |country | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|website= [http://www.harvard.edu/ www.harvard.edu] | |website= [http://www.harvard.edu/ www.harvard.edu] | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Harvard University''' (incorporated as ''The President and Fellows of Harvard College'') is a [[private university]] in [[Cambridge, Massachusetts]]. Founded in 1636, | + | '''Harvard University''' (incorporated as ''The President and Fellows of Harvard College'') is a [[private university]] in [[Cambridge, Massachusetts|Cambridge]], [[Massachusetts]]. Founded in 1636, Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning still operating in the [[United States]]. Founded 16 years after the arrival of the Pilgrims at Plymouth, the University grew from nine students with a single master to an enrollment of more than 18,000 at the beginning of the twenty-first century.<ref>Harvard University, [http://www.news.harvard.edu/guide/intro/index.html The Harvard Guide] Retrieved August 2, 2007.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Harvard was established under [[church]] sponsorship, with the intention of training clergy so that the [[Puritan]] colony would not have to rely on immigrant pastors, but it was not formally affiliated with any denomination. Gradually emancipating itself from [[religion|religious]] control, the university has focused on intellectual training and the highest quality of academic scholarship, becoming known for its emphasis on [[critical thinking]]. Not without criticism, Harvard has weathered the storms of social change, opening its doors to minorities and women. Following student demands for greater autonomy in the 1960s, Harvard, like most institutions of higher learning, largely abandoning any oversight of the private lives of its young undergraduates. Harvard continues its rivalry with [[Yale University|Yale]] and a cooperative, complementary relationship with the neighboring [[Massachusetts Institute of Technology]]. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | A member of the [[Ivy League]], Harvard maintains an outstanding reputation for academic excellence, with numerous notable graduates and faculty. Eight presidents of the United States—[[John Adams]], [[John Quincy Adams]], [[Theodore Roosevelt]], [[Franklin Delano Roosevelt]], [[Rutherford B. Hayes]], [[John F. Kennedy]], [[George W. Bush]], and [[Barack Obama]]—graduated from Harvard. | ||

| − | + | ==Mission and reputation== | |

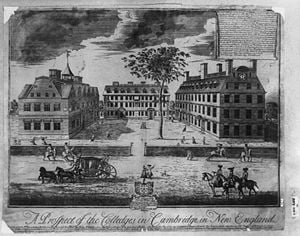

| + | [[Image:Harvard 1740 by William Burgis.jpg|thumb|300px|"A prospect of the colleges in Cambridge in New England." Engraving by [[William Burgis]] from 1740.]] | ||

| + | While there is no university-wide mission statement, Harvard College, the undergraduate division, has its own. The College aims to advance all of the [[science]]s and [[arts]], which was established in the school's original charter: "In brief: Harvard strives to create knowledge, to open the minds of students to that knowledge, and to enable students to take best advantage of their educational opportunities." To further this aim, the school encourages critical thought, [[leadership]], and service.<ref>Harvard University, [http://www.harvard.edu/siteguide/faqs/faq110.html What is Harvard's mission statement?] Retrieved July 13, 2007.</ref> | ||

| − | + | The school enjoys a reputation as one the best (if not the best) universities in the world. Its undergraduate education is considered excellent and the university excels in many different fields of graduate study. The Harvard Law School, Harvard Business School, and Kennedy School of Government are considered at the top of their respective fields. Harvard is often held as the standard against which many other American universities are measured. | |

| − | + | This tremendous success has come with some backlash against the school. The ''[[Wall Street Journal]]'''s Michael Steinberger wrote "A Flood of Crimson Ink," in which he argued that Harvard is over represented in the media due to the disproportionate amount of Harvard graduates that enter the field.<ref>Michael Steinberger, [http://www.opinionjournal.com/forms/printThis.html?id=110006623 "A Flood of Crimson Ink,"] ''Wall Street Journal''. Retrieved July 13, 2007.</ref> ''[[Time]]'' also published an article about the perceived diminishing importance of Harvard in American education due to the emergence of quality alternative institutions.<ref>''Time,'' [http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1226150,00.html "Who Needs Harvard?"] Retrieved July 13, 2007.</ref> Former Dean of the College Harvey Lewis has criticized the school for lack of direction and for coddling the students.<ref>Harry Lewis, ''Excellence Without a Soul: How a Great University Forgot Education'' (Public Affairs, 2006, ISBN 1586483935). </ref> | |

| − | == | + | ==History== |

| + | ===Founding=== | ||

| + | Harvard's founding, in 1636, came in the form of an act of the Massachusetts Bay colony's [[Massachusetts General Court|Great and General Court]]. The institution was named ''[[Harvard College]]'' on March 13, 1639, after its first principal donor, a young clergyman named [[John Harvard (clergyman)|John Harvard]]. A graduate of [[Emmanuel College, Cambridge|Emmanuel College]], [[University of Cambridge]] in [[England]], John Harvard bequeathed about four hundred books in his will to form the basis of the college [[library]] collection, along with half his personal wealth, amounting to several hundred pounds. The earliest known official reference to Harvard as a "university" rather than a "college" occurred in the new [[Massachusetts Constitution]] of 1780. | ||

| − | [[ | + | By all accounts, the chief impetus in the founding of Harvard was to allow the training of home-grown clergy so that the [[Puritan]] colony would not need to rely on immigrating graduates of England's [[University of Oxford|Oxford]] and [[University of Cambridge|Cambridge]] universities for well-educated pastors: |

| + | <blockquote>After God had carried us safe to New England and wee had builded our houses, provided necessaries for our livelihood, rear'd convenient places for God's worship, and settled the civil government: One of the next things we longed for and looked after was to advance learning and perpetuate it to posterity; dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches, when our present ministers shall lie in the dust.<ref name=hds>Harvard University, [http://www.hds.harvard.edu/history.html Harvard Divinity School: History and Mission.] Retrieved August 3, 2007.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | The connection to the Puritans can be seen in the fact that, for its first few centuries of existence, the [[Harvard Board of Overseers]] included, along with certain commonwealth officials, the ministers of six local congregations (Boston, Cambridge, Charlestown, Dorchester, Roxbury, and Watertown). Today, although no longer so empowered, they are still by custom allowed seats on the dais at [[commencement]] exercises. | ||

| − | + | Despite the Puritan atmosphere, from the beginning, the intent was to provide a full [[liberal arts|liberal education]] such as that offered at English universities, including the rudiments of [[mathematics]] and [[science]] ("natural philosophy") as well as [[the classics|classical]] [[literature]] and [[philosophy]]. | |

| − | + | Harvard was also founded as a school to educate [[American Indian]]s in order to train them as ministers among their tribes. Harvard's Charter of 1650 calls for "the education of the English and Indian youth of this Country in knowledge and godliness."<ref name=nativesons>''Harvard University Gazette,'' [http://www.news.harvard.edu/gazette/1997/05.01/RememberingNati.html Remembering Native Sons.] Retrieved October 4, 2006.</ref> Indeed, Harvard and missionaries to the local tribes were intricately connected. The first Bible to be printed in the entire North American continent was printed at Harvard in an Indian language, [[Massachusett language|Massachusett]]. Termed the ''[[Eliot Bible]]'' since it was translated by [[John Eliot]], this book was used to facilitate conversion of Indians, ideally by Harvard-educated Indians themselves. Harvard's first American Indian graduate, [[Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck]] from the [[Wampanoag]] tribe, was a member of the class of 1665.<ref name=nativesons /> Caleb and other students—English and American Indian alike—lived and studied in a dormitory known as the [[Indian College]], which was founded in 1655 under then-President Charles Chauncy. In 1698, it was torn down owing to neglect. The bricks of the former Indian College were later used to build the first Stoughton Hall. Today, a plaque on the SE side of Matthews Hall in Harvard Yard, the approximate site of the Indian College, commemorates the first American Indian students who lived and studied at Harvard University. | |

| − | + | === Growth to preeminence === | |

| − | [[ | + | Between 1800 and 1870, a transformation of Harvard occurred, which E. Digby Baltzell called "privatization."<ref>D.E. Baltzell and H.G. Schneiderman, ''Judgment and Sensibility: Religion and Stratification'' (Transaction Publishers, 1994, ISBN 1-56000-048-1).</ref> Harvard had prospered while [[Federalist Party|Federalists]] controlled state government, but "in 1824, the Federalist Party was finally defeated forever in Massachusetts; the triumphant [[Democratic-Republican Party (United States)|Jeffersonian-Republicans]] cut off all state funds." By 1870, the "magistrates and ministers" on the Board of Overseers had been completely "replaced by Harvard alumni drawn primarily from the ranks of Boston's upper-class business and professional community" and funded by private endowment. |

| − | + | [[Image:HarvardUniversityPresidents1829-1862.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Five [[President of Harvard University|Harvard University Presidents]] sitting in order of when they served. L-R: [[Josiah Quincy III]], [[Edward Everett]], [[Jared Sparks]], [[James Walker (Harvard)|James Walker]], and [[Cornelius Conway Felton]].]] | |

| + | During this period, Harvard experienced unparalleled growth that put it into a different category from other colleges. Ronald Story noted that in 1850 Harvard's total assets were | ||

| + | <blockquote>five times that of Amherst and Williams combined, and three times that of Yale…. By 1850, it was a genuine university, "unequalled in facilities," as a budding scholar put it by any other institution in America—the "greatest University," said another, "in all creation" … all the evidence … points to the four decades from 1815 to 1855 as the era when parents, in Henry Adams' words, began "sending their children to Harvard College for the sake of its social advantages."<ref name=story>R. Story, ''The Forging of an Aristocracy: Harvard and the Boston Upper Class, 1800-1870'' (Wesleyan University Press, 1980, ISBN 0-8195-5044-2). </ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | Harvard was also an early leader in admitting ethnic and religious minorities. Stephen Steinberg, author of ''The Ethnic Myth,'' noted that: | ||

| + | <blockquote>a climate of intolerance prevailed in many eastern colleges long before discriminatory quotas were contemplated … Jews tended to avoid such campuses as Yale and Princeton, which had reputations for bigotry … [while] under President Eliot's administration, Harvard earned a reputation as the most liberal and democratic of the Big Three, and therefore Jews did not feel that the avenue to a prestigious college was altogether closed.<ref>S. Steinberg, ''The Ethnic Myth'' (Beacon Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8070-4153-X). </ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | Harvard | + | In his 1869-1909 tenure as Harvard president, [[Charles William Eliot]] radically transformed Harvard into the pattern of the modern research university. His reforms included elective courses, small classes, and entrance examinations. The Harvard model influenced American education nationally, at both college and secondary levels. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In 1870, one year into Eliot's term, [[Richard Theodore Greener]] became the first African-American to graduate from Harvard College. Seven years later, [[Louis Brandeis]], the first Jewish justice on the [[Supreme Court]], graduated from Harvard Law School. Nevertheless, Harvard became the bastion of a distinctly [[Protestant]] elite—the so-called [[Boston Brahmin]] class—and continued to be so well into the twentieth century. The social milieu of Harvard in the 1880s is depicted in [[Owen Wister]]'s ''Philosophy 4,'' which contrasts the character and demeanor of two undergraduates who "had colonial names (Rogers, I think, and Schuyler)" with that of their tutor, one Oscar Maironi, whose "parents had come over in the steerage."<ref>Owen Wister, {{gutenberg|no=862|name=''Philosophy 4''}} (The Macmillan Company 1914).</ref> | |

| − | + | ===Early twentieth century=== | |

| + | [[Image:Memorial Church, Harvard.jpg|thumb|left|Memorial Church]] | ||

| + | Though Harvard ended required chapel in the mid-1880s, the school remained culturally [[Protestant]], and fears of dilution grew as enrollment of immigrants, [[Catholic]]s, and [[Jew]]s, surged at the turn of the twentieth century. By 1908, Catholics made up nine percent of the freshman class, and between 1906 and 1922, Jewish enrollment at Harvard increased from six to twenty percent. In June 1922, under President Lowell, Harvard announced a Jewish quota. Other universities had done this surreptitiously. Lowell did it in a forthright way, and positioned it as means of "combating" [[anti-Semitism]], writing that "anti-Semitic feeling among the students is increasing, and it grows in proportion to the increase in the number of Jews… when… the number of Jews was small, the race antagonism was small also."<ref>Stephen Steinberg, ''The Academic Melting Pot: Catholics and Jews in American Higher Education'' (Transaction Publishers, 1977, ISBN 0-87855-635-4). </ref> Indeed, Harvard's discriminatory policies, both tacit and explicit, were partly responsible for the founding of [[Boston College]] in 1863 and [[Brandeis University]] in nearby Waltham in 1948.<ref>Michael Levenson, "Brandeis pulls artwork…," ''The Boston Globe'' (May 3, 2006). </ref> | ||

| − | + | ===Modern era=== | |

| − | + | [[Image:Hls langdell hall.jpeg|thumb|right|250 px| Langdell Hall, Harvard Law School]] | |

| − | + | During the twentieth century, Harvard's international reputation grew as a burgeoning endowment and prominent professors expanded the university's scope. Explosive growth in the student population continued with the addition of new graduate schools and the expansion of the undergraduate program. | |

| − | |||

| − | Harvard | + | In the decades immediately after the [[Second World War]], Harvard reformed its admissions policies, as it sought students from a more diverse [[college application|applicant]] pool. Whereas Harvard undergraduates had been almost exclusively white, upper-class alumni of select [[New England]] "feeder schools" such as [[Phillips Academy|Andover]] and [[Groton]], increasing numbers of international, minority, and working-class students had, by the late 1960s, altered the ethnic and socio-economic makeup of the college.<ref>Malka A. Older, [http://www.thecrimson.com/article.aspx?ref=217911 "Preparatory schools and the admissions process,"] ''The Harvard Crimson'' (January 24, 1996). Retrieved July 13, 2007.</ref> Nonetheless, Harvard's undergraduate population remained predominantly male, with about four men attending Harvard College for every woman studying at Radcliffe, founded in 1879, as the "Harvard Annex" for women<ref>Sally Schwager, "Taking up the Challenge: The Origins of Radcliffe," in Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, ''Yards and Gates: Gender in Harvard and Radcliffe History'' (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004).</ref> Following the merger of Harvard and Radcliffe admissions in 1977, the proportion of female undergraduates steadily increased, mirroring a trend throughout higher education in the United States. Harvard's graduate schools, which had accepted females and other groups in greater numbers even before the college, also became more diverse in the post-war period. In 1999, [[Radcliffe College]] merged formally with Harvard University, becoming the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.<ref>Harvard University, [http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~fdo/publications/0203/parents.html#history A History of Harvard College.] Retrieved July 13, 2007.</ref> |

| − | Harvard | + | While Harvard made efforts to recruit women and minorities and to be more involved with social and world issues, the emphasis on learning the process of critical thinking over acquiring knowledge has led to criticism that Harvard has "abdicated its core responsibility to decide what undergraduates ought to learn and has abandoned any effort to shape students' moral character."<ref>Harry R. Lewis, ''Excellence Without a Soul: How a Great University Forgot Education'' (2006).</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The early twenty-first century saw some significant changes, however. In the aftermath of [[Hurricane Katrina]], Harvard, along with numerous other institutions of higher education across the [[United States]] and [[Canada]], offered to take in students from the Gulf region who were unable to attend universities and colleges that were closed for the fall semester. Twenty-five students were admitted to the College, and the [[Harvard Law School|Law School]] made similar arrangements. Tuition was not charged and housing was provided.<ref>Lawrence H. Summers, [http://president.harvard.edu/speeches/2005/0902_katrina.html Letter to the Harvard community regarding Hurricane Katrina,] Harvard University President, Cambridge, Massachusetts, September 2, 2005. Retrieved September 24, 2008.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | On June 30, 2006, then-President of Harvard [[Lawrence Summers|Lawrence H. Summers]] resigned after a whirlwind of controversies (stemming partially from comments he made on a possible correlation between gender and success in certain academic fields). [[Derek Bok]], who had served as President of Harvard from 1971–1991, returned to serve as an interim president until a permanent replacement could be found. On February 8, 2007, [[The Harvard Crimson]] announced that Drew Gilpin Faust had been selected as the next president, the first woman to serve in the position.<ref>''The Harvard Chrimson,'' [http://www.thecrimson.com/article.aspx?ref=517005 IT'S FAUST: Radcliffe dean, if approved by Overseers, will be Harvard's first female leader.] Retrieved September 24, 2008.</ref> | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | During a campus news conference on campus Faust stated, "I hope that my own appointment can be one symbol of an opening of opportunities that would have been inconceivable even a generation ago." But she also added, "I'm not the woman president of Harvard, I'm the president of Harvard."<ref>Jesse Harlan Alderman, [http://www.boston.com/news/nation/articles/2007/02/11/harvard_names_its_1st_female_president/ Harvard names 1st woman president,] ''The Boston Globe,'' February 11, 2007. Retrieved September 24, 2008.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Facilities== | ||

===Library system and museums=== | ===Library system and museums=== | ||

| − | The [[Harvard University Library]] System, centered | + | [[Image:Cambridge Harvard Square.JPG|thumb|300 px| Harvard Square, Cambridge, Massachusetts]] [[Image:Harvard Museum of Natural History 050227.jpg|thumb|right|250 px|Harvard Museum of Natural History]] |

| − | + | The [[Harvard University Library]] System, centered on [[Widener Library]] in [[Harvard Yard]] and comprising over 90 individual libraries and over 15.3 million volumes, is one of the largest [[library]] collections in the world.<ref>Harvard University, [http://www.hno.harvard.edu/guide/to_do/to_do6.html Largest Academic Library in the World.] Retrieved September 16, 2006.</ref> Cabot Science Library, Lamont Library, and Widener Library are three of the most popular libraries for undergraduates to use, with easy access and central locations. Houghton Library is the primary repository for Harvard's rare books and manuscripts. America's oldest collection of maps, gazetteers, and atlases both old and new is stored in Pusey Library and open to the public. The largest collection of East-Asian language material outside of East Asia is held in the Harvard-Yenching Library. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Harvard operates several arts, cultural, and scientific [[museum]]s: | |

| + | :*The [[Harvard Art Museums]], including: | ||

| + | :** The [[Fogg Museum of Art]], with galleries featuring history of Western art from the Middle Ages to the present. Particular strengths are in Italian [[Early Renaissance painting|early Renaissance]], British [[pre-Raphaelite]], and nineteenth century French art) | ||

| + | :** The [[Busch-Reisinger Museum]], formerly the Germanic Museum, covers central and northern European art | ||

| + | :** The [[Arthur M. Sackler Museum]], which includes ancient, Asian, Islamic and later Indian art | ||

| + | :* The [[Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology]], specializing in the cultural history and civilizations of the Western Hemisphere | ||

| + | :* The [[Semitic Museum]] | ||

| + | :* The [[Harvard Museum of Natural History]] complex, including: | ||

| + | :**The [[Harvard University Herbaria]], which contains the famous Blaschka [[Glass Flowers]] exhibit | ||

| + | :**The [[Museum of Comparative Zoology]] | ||

| + | :**The [[Harvard Mineralogical Museum]] | ||

| − | + | ===Athletics=== | |

| + | [[Image: Harvard Stadium, Dudesleeper.jpg|thumb|250px|left|[[Harvard Stadium]]]] | ||

| − | [[ | + | Harvard has several athletic facilities, such as the [[Lavietes Pavilion]], a multi-purpose arena and home to the Harvard [[basketball]] teams. The Malkin Athletic Center, known as the "MAC," serves both as the university's primary recreation facility and as a satellite location for several varsity sports. The five story building includes two cardio rooms, an Olympic-size [[swimming]] pool, a smaller pool for aquaerobics and other activities, a mezzanine, where all types of classes are held at all hours of the day, and an indoor cycling studio, three weight rooms, and a three-court gym floor to play basketball. The MAC also offers personal trainers and specialty classes. The MAC is also home to Harvard volleyball, [[fencing]], and [[wrestling]]. The offices of women's [[field hockey]], [[lacrosse]], [[soccer]], [[softball]], and men's soccer are also in the MAC. |

| − | + | [[Weld Boathouse]] and Newell Boathouse house the women's and men's [[rowing]] teams, respectively. The men's crew also uses the Red Top complex in Ledyard CT, as their training camp for the annual [[Harvard-Yale Regatta]]. The Bright Hockey Center hosts the Harvard hockey teams, and the Murr Center serves both as a home for Harvard's [[squash (sport)|squash]] and [[tennis]] teams as well as strength and conditioning center for all athletic sports. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | As of 2006, there were 41 Division I intercollegiate [[Varsity team|varsity]] [[sports]] teams for women and men at Harvard, more than at any other NCAA Division I college in the country. As with other [[Ivy League]] universities, [[Harvard]] does not offer athletic scholarships. | |

| − | + | ===Overview of the campus=== | |

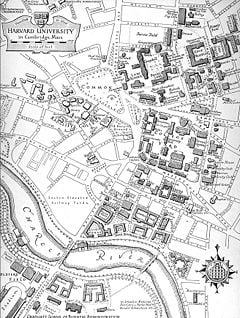

| + | [[Image:Harvard University map (older, date unknown).jpg|thumb|left|240px|Harvard University campus (old map)]] | ||

| + | The main campus is centered around [[Harvard Yard]] in central Cambridge, and extends into the surrounding [[Harvard Square]] neighborhood. The Harvard Business School and many of the university's athletics facilities, including [[Harvard Stadium]], are located in [[Allston, Massachusetts|Allston]], on the other side of the [[Charles River]] from Harvard Square. [[Harvard Medical School]] and the Harvard School of Public Health are located in the [[Longwood Medical and Academic Area]] in [[Boston, Massachusetts|Boston]]. | ||

| − | + | Harvard Yard itself contains the central administrative offices and main [[library|libraries]] of the university, several academic buildings, Memorial Church, and the majority of the freshman dormitories. Sophomore, junior, and senior undergraduates live in twelve residential Houses, nine of which are south of Harvard Yard along or near the [[Charles River]]. The other three are located in a residential neighborhood half a mile northwest of the Yard at the [[Quadrangle (Harvard)|Quadrangle]], which formerly housed [[Radcliffe College]] students until Radcliffe merged its residential system with Harvard. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Radcliffe Yard]], formerly the center of the campus of Radcliffe College (and now home of the Radcliffe Institute), is halfway between Harvard Yard and the Quadrangle, adjacent to the Graduate School of Education. | [[Radcliffe Yard]], formerly the center of the campus of Radcliffe College (and now home of the Radcliffe Institute), is halfway between Harvard Yard and the Quadrangle, adjacent to the Graduate School of Education. | ||

===Satellite facilities=== | ===Satellite facilities=== | ||

| − | Apart from its major Cambridge/Allston and Longwood campuses, Harvard owns and operates | + | Apart from its major Cambridge/Allston and Longwood campuses, Harvard owns and operates [[Arnold Arboretum]], in the [[Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts|Jamaica Plain]] area of [[Boston]]; the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, in [[Washington, D.C.]]; and the [[Villa I Tatti]] research center in [[Florence]], [[Italy]]. |

| − | [[Arnold Arboretum]], in the [[Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts|Jamaica Plain]] area of Boston; | ||

| − | the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, in [[Washington, D.C.]]; | ||

| − | and the [[Villa I Tatti]] research center in [[Florence]], Italy. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Schools== |

| − | + | Harvard is governed by two boards, the [[President and Fellows of Harvard College]], also known as the Harvard Corporation and founded in 1650, and the [[Harvard Board of Overseers]]. The [[President of Harvard University]] is the day-to-day administrator of Harvard and is appointed by and responsible to the Harvard Corporation. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | The University has an enrollment of more than 18,000 degree candidates, with an additional 13,000 students enrolled in one or more courses in the Harvard Extension School. Over 14,000 people work at Harvard, including more than 2,000 faculty. There are also 7,000 faculty appointments in affiliated teaching hospitals.<ref>Harvard University, [http://www.news.harvard.edu/guide/intro/index.html The Harvard Guide.] Retrieved August 2, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | Harvard today has nine faculties, listed below in order of foundation: | |

| − | [[Image:Harvard | + | [[Image: Harvard Yard, Dudesleeper.jpg|right|thumb|250px|Harvard Yard with freshman dorms in the background]] |

| − | Harvard | + | *The [[Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences|Faculty of Arts and Sciences]] and its sub-faculty, the [[Harvard Division of Engineering and Applied Sciences|Division of Engineering and Applied Sciences]], which together serve: |

| − | + | **[[Harvard College]], the university's undergraduate portion (1636) | |

| − | + | **The [[Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences|Graduate School of Arts and Sciences]] (organized 1872) | |

| − | + | **The [[Harvard Division of Continuing Education]], including [[Harvard Extension School]] (1909) and [[Harvard Summer School]] (1871) | |

| − | [[ | + | *The Faculty of Medicine, including the [[Harvard Medical School|Medical School]] (1782) and the [[Harvard School of Dental Medicine]] (1867). |

| − | + | *[[Harvard Divinity School]] (1816) | |

| − | + | *[[Harvard Law School]] (1817) | |

| − | + | *[[Harvard Business School]] (1908) | |

| − | + | *The [[Harvard Graduate School of Design|Graduate School of Design]] (1914) | |

| − | + | *The [[Harvard Graduate School of Education|Graduate School of Education]] (1920) | |

| − | + | *The [[Harvard School of Public Health|School of Public Health]] (1922) | |

| − | + | *The [[Kennedy School of Government|John F. Kennedy School of Government]] (1936) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In addition, there is the [[Forsyth Institute]] of Dental Research. In 1999, the former [[Radcliffe College]] was reorganized as the [[Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Student life== | |

| − | + | [[Image:Rhinoceros Sculpture, Biological Sciences Building, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.JPG|thumb|right|250px|A stone Rhinoceros sculpture "Bessie" in front of the Biological Laboratories.]] | |

| − | + | Notable student activities include ''[[Harvard Lampoon]],'' the world's oldest [[humor]] [[magazine]]; the ''[[the Harvard Advocate|Harvard Advocate]],'' one of the nation's oldest literary magazines and the oldest current publication at Harvard; and the [[Hasty Pudding Theatricals]], which produces an annual burlesque and celebrates notable actors at its [[Hasty Pudding Man of the Year|Man of the Year]] and [[Hasty Pudding Woman of the Year|Woman of the Year]] ceremonies. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The [[Harvard Glee Club]] is the oldest college [[chorus]] in America, and the [[University Choir]], the [[choir]] of Harvard's [[Memorial Church]], is the oldest choir in America affiliated with a university. | |

| − | + | The [[Harvard-Radcliffe Orchestra]], composed mainly of undergraduates, was founded in 1808, as the Pierian Sodality (thus making it technically older than the [[New York Philharmonic]], which is the oldest professional [[orchestra]] in America), and has been performing as a symphony orchestra since the 1950s. The school also has a number of [[a cappella]] singing groups, the oldest of which is the [[Harvard Krokodiloes]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Traditions== |

| − | [[ | + | Harvard has a friendly rivalry with the [[Massachusetts Institute of Technology]] which dates back to 1900, when a merger of the two schools was frequently discussed and at one point officially agreed upon (ultimately canceled by Massachusetts courts). Today, the two schools cooperate as much as they compete, with many joint conferences and programs, including the [[Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology]], the Harvard-MIT Data Center and the Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology. In addition, students at the two schools can [[cross-registration|cross-register]] in undergraduate or graduate classes without any additional fees, for credits toward their own school's degrees. The relationship and proximity between the two institutions is a remarkable phenomenon, considering their stature; according to ''[[The Times Higher Education Supplement]]'' of [[London]], "The U.S. has the world’s top two universities by our reckoning—Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, neighbors on the Charles River."<ref>www.thes.co.uk, [http://www.thes.co.uk/worldrankings/ Times Higher Education Supplement World Rankings 2006.] Retrieved August 2, 2007.</ref> |

| − | + | Harvard's athletic rivalry with [[Yale University|Yale]] is intense in every sport in which they meet, coming to a climax each fall in their annual American Football meeting, which dates to 1875, and is usually called simply "[[The Game (college football)|The Game]]." While Harvard's [[American football|football]] team is no longer one of the country's best (it won the [[Rose Bowl Game|Rose Bowl]] in 1920) as it often was during football's early days, it, along with Yale, has influenced the way the game is played. In 1903, [[Harvard Stadium]] introduced a new era into football with the first-ever permanent reinforced concrete stadium of its kind in the country. The sport eventually adopted the forward pass (invented by [[Yale]] coach [[Walter Camp]]) because of the stadium's structure. | |

| − | + | Older than The Game by 23 years, the [[Harvard-Yale Regatta]] was the original source of the athletic rivalry between the two schools. It is held annually in June on the Thames river in eastern [[Connecticut]]. The Harvard Crew is considered to be one of the top teams in the country in [[Sport rowing|rowing]]. | |

| − | ==Notable | + | ==Notable alumni== |

| − | + | Over its history, Harvard has graduated many famous alumni, along with a few infamous ones. Among the best-known are political leaders [[John Hancock]], [[John Adams]], [[Theodore Roosevelt]], [[Franklin Roosevelt]], [[Barack Obama]], and [[John F. Kennedy]]; philosopher [[Henry David Thoreau]] and author [[Ralph Waldo Emerson]]; poets [[Wallace Stevens]], [[T.S. Eliot]], and [[E.E. Cummings]]; composer [[Leonard Bernstein]]; actor [[Jack Lemmon]]; architect [[Philip Johnson]], and civil rights leader [[W.E.B. Du Bois]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Seventy-five [[Nobel Prize]] winners are affiliated with the university. Since 1974, nineteen Nobel Prize winners and fifteen winners of the American literary award, the [[Pulitzer Prize]], have served on the Harvard faculty. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | < | + | <references/> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | *John T. | + | *Bethell, John T. 1998. ''Harvard Observed: An Illustrated History of the University in the Twentieth Century''. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-37733-8. |

| − | * | + | *Douthat, Ross. 2006. ''Privilege: Harvard and the Education of the Ruling Class''. Hyperion. ISBN 1401307558. |

| − | *Hoerr, John | + | *Hoerr, John. 1997. ''We Can't Eat Prestige: The Women Who Organized Harvard''. Temple University Press. ISBN 1-56639-535-6. |

| − | + | *Karabel, Jerome. 2006. ''The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton.'' Mariner Books. ISBN 061877355X. | |

| − | + | *Keller, Morton, and Phyllis Keller. 2007. ''Making Harvard Modern: The Rise of America's University''. Oxford University Press. ISBN 019532515X. | |

| + | *Lewis, Harry R. 2006. ''Excellence Without a Soul: How a Great University Forgot Education''. PublicAffairs. ISBN 1586483935. | ||

| + | *Trumpbour, John (ed.). 1989. ''How Harvard Rules''. Boston: South End Press. ISBN 0-89608-283-0. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved August 4, 2017. | |

| − | + | *[http://www.harvard.edu/ Harvard University.] | |

| − | *[http://www.harvard.edu/ Harvard University] | ||

{{Ivy League}} | {{Ivy League}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credits|Harvard_University|95270555|}} | {{Credits|Harvard_University|95270555|}} | ||

Latest revision as of 16:50, 30 January 2022

| |

| Motto | Veritas (Truth) |

|---|---|

| Established | September 8, 1636 (OS), September 18, 1636 (NS) |

| Type | Private |

| Location | Cambridge, Mass. U.S. |

| Website | www.harvard.edu |

Harvard University (incorporated as The President and Fellows of Harvard College) is a private university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning still operating in the United States. Founded 16 years after the arrival of the Pilgrims at Plymouth, the University grew from nine students with a single master to an enrollment of more than 18,000 at the beginning of the twenty-first century.[1]

Harvard was established under church sponsorship, with the intention of training clergy so that the Puritan colony would not have to rely on immigrant pastors, but it was not formally affiliated with any denomination. Gradually emancipating itself from religious control, the university has focused on intellectual training and the highest quality of academic scholarship, becoming known for its emphasis on critical thinking. Not without criticism, Harvard has weathered the storms of social change, opening its doors to minorities and women. Following student demands for greater autonomy in the 1960s, Harvard, like most institutions of higher learning, largely abandoning any oversight of the private lives of its young undergraduates. Harvard continues its rivalry with Yale and a cooperative, complementary relationship with the neighboring Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

A member of the Ivy League, Harvard maintains an outstanding reputation for academic excellence, with numerous notable graduates and faculty. Eight presidents of the United States—John Adams, John Quincy Adams, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Rutherford B. Hayes, John F. Kennedy, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama—graduated from Harvard.

Mission and reputation

While there is no university-wide mission statement, Harvard College, the undergraduate division, has its own. The College aims to advance all of the sciences and arts, which was established in the school's original charter: "In brief: Harvard strives to create knowledge, to open the minds of students to that knowledge, and to enable students to take best advantage of their educational opportunities." To further this aim, the school encourages critical thought, leadership, and service.[2]

The school enjoys a reputation as one the best (if not the best) universities in the world. Its undergraduate education is considered excellent and the university excels in many different fields of graduate study. The Harvard Law School, Harvard Business School, and Kennedy School of Government are considered at the top of their respective fields. Harvard is often held as the standard against which many other American universities are measured.

This tremendous success has come with some backlash against the school. The Wall Street Journal's Michael Steinberger wrote "A Flood of Crimson Ink," in which he argued that Harvard is over represented in the media due to the disproportionate amount of Harvard graduates that enter the field.[3] Time also published an article about the perceived diminishing importance of Harvard in American education due to the emergence of quality alternative institutions.[4] Former Dean of the College Harvey Lewis has criticized the school for lack of direction and for coddling the students.[5]

History

Founding

Harvard's founding, in 1636, came in the form of an act of the Massachusetts Bay colony's Great and General Court. The institution was named Harvard College on March 13, 1639, after its first principal donor, a young clergyman named John Harvard. A graduate of Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge in England, John Harvard bequeathed about four hundred books in his will to form the basis of the college library collection, along with half his personal wealth, amounting to several hundred pounds. The earliest known official reference to Harvard as a "university" rather than a "college" occurred in the new Massachusetts Constitution of 1780.

By all accounts, the chief impetus in the founding of Harvard was to allow the training of home-grown clergy so that the Puritan colony would not need to rely on immigrating graduates of England's Oxford and Cambridge universities for well-educated pastors:

After God had carried us safe to New England and wee had builded our houses, provided necessaries for our livelihood, rear'd convenient places for God's worship, and settled the civil government: One of the next things we longed for and looked after was to advance learning and perpetuate it to posterity; dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches, when our present ministers shall lie in the dust.[6]

The connection to the Puritans can be seen in the fact that, for its first few centuries of existence, the Harvard Board of Overseers included, along with certain commonwealth officials, the ministers of six local congregations (Boston, Cambridge, Charlestown, Dorchester, Roxbury, and Watertown). Today, although no longer so empowered, they are still by custom allowed seats on the dais at commencement exercises.

Despite the Puritan atmosphere, from the beginning, the intent was to provide a full liberal education such as that offered at English universities, including the rudiments of mathematics and science ("natural philosophy") as well as classical literature and philosophy.

Harvard was also founded as a school to educate American Indians in order to train them as ministers among their tribes. Harvard's Charter of 1650 calls for "the education of the English and Indian youth of this Country in knowledge and godliness."[7] Indeed, Harvard and missionaries to the local tribes were intricately connected. The first Bible to be printed in the entire North American continent was printed at Harvard in an Indian language, Massachusett. Termed the Eliot Bible since it was translated by John Eliot, this book was used to facilitate conversion of Indians, ideally by Harvard-educated Indians themselves. Harvard's first American Indian graduate, Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck from the Wampanoag tribe, was a member of the class of 1665.[7] Caleb and other students—English and American Indian alike—lived and studied in a dormitory known as the Indian College, which was founded in 1655 under then-President Charles Chauncy. In 1698, it was torn down owing to neglect. The bricks of the former Indian College were later used to build the first Stoughton Hall. Today, a plaque on the SE side of Matthews Hall in Harvard Yard, the approximate site of the Indian College, commemorates the first American Indian students who lived and studied at Harvard University.

Growth to preeminence

Between 1800 and 1870, a transformation of Harvard occurred, which E. Digby Baltzell called "privatization."[8] Harvard had prospered while Federalists controlled state government, but "in 1824, the Federalist Party was finally defeated forever in Massachusetts; the triumphant Jeffersonian-Republicans cut off all state funds." By 1870, the "magistrates and ministers" on the Board of Overseers had been completely "replaced by Harvard alumni drawn primarily from the ranks of Boston's upper-class business and professional community" and funded by private endowment.

During this period, Harvard experienced unparalleled growth that put it into a different category from other colleges. Ronald Story noted that in 1850 Harvard's total assets were

five times that of Amherst and Williams combined, and three times that of Yale…. By 1850, it was a genuine university, "unequalled in facilities," as a budding scholar put it by any other institution in America—the "greatest University," said another, "in all creation" … all the evidence … points to the four decades from 1815 to 1855 as the era when parents, in Henry Adams' words, began "sending their children to Harvard College for the sake of its social advantages."[9]

Harvard was also an early leader in admitting ethnic and religious minorities. Stephen Steinberg, author of The Ethnic Myth, noted that:

a climate of intolerance prevailed in many eastern colleges long before discriminatory quotas were contemplated … Jews tended to avoid such campuses as Yale and Princeton, which had reputations for bigotry … [while] under President Eliot's administration, Harvard earned a reputation as the most liberal and democratic of the Big Three, and therefore Jews did not feel that the avenue to a prestigious college was altogether closed.[10]

In his 1869-1909 tenure as Harvard president, Charles William Eliot radically transformed Harvard into the pattern of the modern research university. His reforms included elective courses, small classes, and entrance examinations. The Harvard model influenced American education nationally, at both college and secondary levels.

In 1870, one year into Eliot's term, Richard Theodore Greener became the first African-American to graduate from Harvard College. Seven years later, Louis Brandeis, the first Jewish justice on the Supreme Court, graduated from Harvard Law School. Nevertheless, Harvard became the bastion of a distinctly Protestant elite—the so-called Boston Brahmin class—and continued to be so well into the twentieth century. The social milieu of Harvard in the 1880s is depicted in Owen Wister's Philosophy 4, which contrasts the character and demeanor of two undergraduates who "had colonial names (Rogers, I think, and Schuyler)" with that of their tutor, one Oscar Maironi, whose "parents had come over in the steerage."[11]

Early twentieth century

Though Harvard ended required chapel in the mid-1880s, the school remained culturally Protestant, and fears of dilution grew as enrollment of immigrants, Catholics, and Jews, surged at the turn of the twentieth century. By 1908, Catholics made up nine percent of the freshman class, and between 1906 and 1922, Jewish enrollment at Harvard increased from six to twenty percent. In June 1922, under President Lowell, Harvard announced a Jewish quota. Other universities had done this surreptitiously. Lowell did it in a forthright way, and positioned it as means of "combating" anti-Semitism, writing that "anti-Semitic feeling among the students is increasing, and it grows in proportion to the increase in the number of Jews… when… the number of Jews was small, the race antagonism was small also."[12] Indeed, Harvard's discriminatory policies, both tacit and explicit, were partly responsible for the founding of Boston College in 1863 and Brandeis University in nearby Waltham in 1948.[13]

Modern era

During the twentieth century, Harvard's international reputation grew as a burgeoning endowment and prominent professors expanded the university's scope. Explosive growth in the student population continued with the addition of new graduate schools and the expansion of the undergraduate program.

In the decades immediately after the Second World War, Harvard reformed its admissions policies, as it sought students from a more diverse applicant pool. Whereas Harvard undergraduates had been almost exclusively white, upper-class alumni of select New England "feeder schools" such as Andover and Groton, increasing numbers of international, minority, and working-class students had, by the late 1960s, altered the ethnic and socio-economic makeup of the college.[14] Nonetheless, Harvard's undergraduate population remained predominantly male, with about four men attending Harvard College for every woman studying at Radcliffe, founded in 1879, as the "Harvard Annex" for women[15] Following the merger of Harvard and Radcliffe admissions in 1977, the proportion of female undergraduates steadily increased, mirroring a trend throughout higher education in the United States. Harvard's graduate schools, which had accepted females and other groups in greater numbers even before the college, also became more diverse in the post-war period. In 1999, Radcliffe College merged formally with Harvard University, becoming the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.[16]

While Harvard made efforts to recruit women and minorities and to be more involved with social and world issues, the emphasis on learning the process of critical thinking over acquiring knowledge has led to criticism that Harvard has "abdicated its core responsibility to decide what undergraduates ought to learn and has abandoned any effort to shape students' moral character."[17]

The early twenty-first century saw some significant changes, however. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Harvard, along with numerous other institutions of higher education across the United States and Canada, offered to take in students from the Gulf region who were unable to attend universities and colleges that were closed for the fall semester. Twenty-five students were admitted to the College, and the Law School made similar arrangements. Tuition was not charged and housing was provided.[18]

On June 30, 2006, then-President of Harvard Lawrence H. Summers resigned after a whirlwind of controversies (stemming partially from comments he made on a possible correlation between gender and success in certain academic fields). Derek Bok, who had served as President of Harvard from 1971–1991, returned to serve as an interim president until a permanent replacement could be found. On February 8, 2007, The Harvard Crimson announced that Drew Gilpin Faust had been selected as the next president, the first woman to serve in the position.[19]

During a campus news conference on campus Faust stated, "I hope that my own appointment can be one symbol of an opening of opportunities that would have been inconceivable even a generation ago." But she also added, "I'm not the woman president of Harvard, I'm the president of Harvard."[20]

Facilities

Library system and museums

The Harvard University Library System, centered on Widener Library in Harvard Yard and comprising over 90 individual libraries and over 15.3 million volumes, is one of the largest library collections in the world.[21] Cabot Science Library, Lamont Library, and Widener Library are three of the most popular libraries for undergraduates to use, with easy access and central locations. Houghton Library is the primary repository for Harvard's rare books and manuscripts. America's oldest collection of maps, gazetteers, and atlases both old and new is stored in Pusey Library and open to the public. The largest collection of East-Asian language material outside of East Asia is held in the Harvard-Yenching Library.

Harvard operates several arts, cultural, and scientific museums:

- The Harvard Art Museums, including:

- The Fogg Museum of Art, with galleries featuring history of Western art from the Middle Ages to the present. Particular strengths are in Italian early Renaissance, British pre-Raphaelite, and nineteenth century French art)

- The Busch-Reisinger Museum, formerly the Germanic Museum, covers central and northern European art

- The Arthur M. Sackler Museum, which includes ancient, Asian, Islamic and later Indian art

- The Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, specializing in the cultural history and civilizations of the Western Hemisphere

- The Semitic Museum

- The Harvard Museum of Natural History complex, including:

- The Harvard University Herbaria, which contains the famous Blaschka Glass Flowers exhibit

- The Museum of Comparative Zoology

- The Harvard Mineralogical Museum

- The Harvard Art Museums, including:

Athletics

Harvard has several athletic facilities, such as the Lavietes Pavilion, a multi-purpose arena and home to the Harvard basketball teams. The Malkin Athletic Center, known as the "MAC," serves both as the university's primary recreation facility and as a satellite location for several varsity sports. The five story building includes two cardio rooms, an Olympic-size swimming pool, a smaller pool for aquaerobics and other activities, a mezzanine, where all types of classes are held at all hours of the day, and an indoor cycling studio, three weight rooms, and a three-court gym floor to play basketball. The MAC also offers personal trainers and specialty classes. The MAC is also home to Harvard volleyball, fencing, and wrestling. The offices of women's field hockey, lacrosse, soccer, softball, and men's soccer are also in the MAC.

Weld Boathouse and Newell Boathouse house the women's and men's rowing teams, respectively. The men's crew also uses the Red Top complex in Ledyard CT, as their training camp for the annual Harvard-Yale Regatta. The Bright Hockey Center hosts the Harvard hockey teams, and the Murr Center serves both as a home for Harvard's squash and tennis teams as well as strength and conditioning center for all athletic sports.

As of 2006, there were 41 Division I intercollegiate varsity sports teams for women and men at Harvard, more than at any other NCAA Division I college in the country. As with other Ivy League universities, Harvard does not offer athletic scholarships.

Overview of the campus

The main campus is centered around Harvard Yard in central Cambridge, and extends into the surrounding Harvard Square neighborhood. The Harvard Business School and many of the university's athletics facilities, including Harvard Stadium, are located in Allston, on the other side of the Charles River from Harvard Square. Harvard Medical School and the Harvard School of Public Health are located in the Longwood Medical and Academic Area in Boston.

Harvard Yard itself contains the central administrative offices and main libraries of the university, several academic buildings, Memorial Church, and the majority of the freshman dormitories. Sophomore, junior, and senior undergraduates live in twelve residential Houses, nine of which are south of Harvard Yard along or near the Charles River. The other three are located in a residential neighborhood half a mile northwest of the Yard at the Quadrangle, which formerly housed Radcliffe College students until Radcliffe merged its residential system with Harvard.

Radcliffe Yard, formerly the center of the campus of Radcliffe College (and now home of the Radcliffe Institute), is halfway between Harvard Yard and the Quadrangle, adjacent to the Graduate School of Education.

Satellite facilities

Apart from its major Cambridge/Allston and Longwood campuses, Harvard owns and operates Arnold Arboretum, in the Jamaica Plain area of Boston; the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, in Washington, D.C.; and the Villa I Tatti research center in Florence, Italy.

Schools

Harvard is governed by two boards, the President and Fellows of Harvard College, also known as the Harvard Corporation and founded in 1650, and the Harvard Board of Overseers. The President of Harvard University is the day-to-day administrator of Harvard and is appointed by and responsible to the Harvard Corporation.

The University has an enrollment of more than 18,000 degree candidates, with an additional 13,000 students enrolled in one or more courses in the Harvard Extension School. Over 14,000 people work at Harvard, including more than 2,000 faculty. There are also 7,000 faculty appointments in affiliated teaching hospitals.[22]

Harvard today has nine faculties, listed below in order of foundation:

- The Faculty of Arts and Sciences and its sub-faculty, the Division of Engineering and Applied Sciences, which together serve:

- Harvard College, the university's undergraduate portion (1636)

- The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (organized 1872)

- The Harvard Division of Continuing Education, including Harvard Extension School (1909) and Harvard Summer School (1871)

- The Faculty of Medicine, including the Medical School (1782) and the Harvard School of Dental Medicine (1867).

- Harvard Divinity School (1816)

- Harvard Law School (1817)

- Harvard Business School (1908)

- The Graduate School of Design (1914)

- The Graduate School of Education (1920)

- The School of Public Health (1922)

- The John F. Kennedy School of Government (1936)

In addition, there is the Forsyth Institute of Dental Research. In 1999, the former Radcliffe College was reorganized as the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

Student life

Notable student activities include Harvard Lampoon, the world's oldest humor magazine; the Harvard Advocate, one of the nation's oldest literary magazines and the oldest current publication at Harvard; and the Hasty Pudding Theatricals, which produces an annual burlesque and celebrates notable actors at its Man of the Year and Woman of the Year ceremonies.

The Harvard Glee Club is the oldest college chorus in America, and the University Choir, the choir of Harvard's Memorial Church, is the oldest choir in America affiliated with a university.

The Harvard-Radcliffe Orchestra, composed mainly of undergraduates, was founded in 1808, as the Pierian Sodality (thus making it technically older than the New York Philharmonic, which is the oldest professional orchestra in America), and has been performing as a symphony orchestra since the 1950s. The school also has a number of a cappella singing groups, the oldest of which is the Harvard Krokodiloes.

Traditions

Harvard has a friendly rivalry with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology which dates back to 1900, when a merger of the two schools was frequently discussed and at one point officially agreed upon (ultimately canceled by Massachusetts courts). Today, the two schools cooperate as much as they compete, with many joint conferences and programs, including the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, the Harvard-MIT Data Center and the Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology. In addition, students at the two schools can cross-register in undergraduate or graduate classes without any additional fees, for credits toward their own school's degrees. The relationship and proximity between the two institutions is a remarkable phenomenon, considering their stature; according to The Times Higher Education Supplement of London, "The U.S. has the world’s top two universities by our reckoning—Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, neighbors on the Charles River."[23]

Harvard's athletic rivalry with Yale is intense in every sport in which they meet, coming to a climax each fall in their annual American Football meeting, which dates to 1875, and is usually called simply "The Game." While Harvard's football team is no longer one of the country's best (it won the Rose Bowl in 1920) as it often was during football's early days, it, along with Yale, has influenced the way the game is played. In 1903, Harvard Stadium introduced a new era into football with the first-ever permanent reinforced concrete stadium of its kind in the country. The sport eventually adopted the forward pass (invented by Yale coach Walter Camp) because of the stadium's structure.

Older than The Game by 23 years, the Harvard-Yale Regatta was the original source of the athletic rivalry between the two schools. It is held annually in June on the Thames river in eastern Connecticut. The Harvard Crew is considered to be one of the top teams in the country in rowing.

Notable alumni

Over its history, Harvard has graduated many famous alumni, along with a few infamous ones. Among the best-known are political leaders John Hancock, John Adams, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt, Barack Obama, and John F. Kennedy; philosopher Henry David Thoreau and author Ralph Waldo Emerson; poets Wallace Stevens, T.S. Eliot, and E.E. Cummings; composer Leonard Bernstein; actor Jack Lemmon; architect Philip Johnson, and civil rights leader W.E.B. Du Bois.

Seventy-five Nobel Prize winners are affiliated with the university. Since 1974, nineteen Nobel Prize winners and fifteen winners of the American literary award, the Pulitzer Prize, have served on the Harvard faculty.

Notes

- ↑ Harvard University, The Harvard Guide Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- ↑ Harvard University, What is Harvard's mission statement? Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- ↑ Michael Steinberger, "A Flood of Crimson Ink," Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- ↑ Time, "Who Needs Harvard?" Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- ↑ Harry Lewis, Excellence Without a Soul: How a Great University Forgot Education (Public Affairs, 2006, ISBN 1586483935).

- ↑ Harvard University, Harvard Divinity School: History and Mission. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Harvard University Gazette, Remembering Native Sons. Retrieved October 4, 2006.

- ↑ D.E. Baltzell and H.G. Schneiderman, Judgment and Sensibility: Religion and Stratification (Transaction Publishers, 1994, ISBN 1-56000-048-1).

- ↑ R. Story, The Forging of an Aristocracy: Harvard and the Boston Upper Class, 1800-1870 (Wesleyan University Press, 1980, ISBN 0-8195-5044-2).

- ↑ S. Steinberg, The Ethnic Myth (Beacon Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8070-4153-X).

- ↑ Owen Wister, 'Philosophy 4', available for free via Project Gutenberg (The Macmillan Company 1914).

- ↑ Stephen Steinberg, The Academic Melting Pot: Catholics and Jews in American Higher Education (Transaction Publishers, 1977, ISBN 0-87855-635-4).

- ↑ Michael Levenson, "Brandeis pulls artwork…," The Boston Globe (May 3, 2006).

- ↑ Malka A. Older, "Preparatory schools and the admissions process," The Harvard Crimson (January 24, 1996). Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- ↑ Sally Schwager, "Taking up the Challenge: The Origins of Radcliffe," in Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, Yards and Gates: Gender in Harvard and Radcliffe History (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004).

- ↑ Harvard University, A History of Harvard College. Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- ↑ Harry R. Lewis, Excellence Without a Soul: How a Great University Forgot Education (2006).

- ↑ Lawrence H. Summers, Letter to the Harvard community regarding Hurricane Katrina, Harvard University President, Cambridge, Massachusetts, September 2, 2005. Retrieved September 24, 2008.

- ↑ The Harvard Chrimson, IT'S FAUST: Radcliffe dean, if approved by Overseers, will be Harvard's first female leader. Retrieved September 24, 2008.

- ↑ Jesse Harlan Alderman, Harvard names 1st woman president, The Boston Globe, February 11, 2007. Retrieved September 24, 2008.

- ↑ Harvard University, Largest Academic Library in the World. Retrieved September 16, 2006.

- ↑ Harvard University, The Harvard Guide. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- ↑ www.thes.co.uk, Times Higher Education Supplement World Rankings 2006. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bethell, John T. 1998. Harvard Observed: An Illustrated History of the University in the Twentieth Century. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-37733-8.

- Douthat, Ross. 2006. Privilege: Harvard and the Education of the Ruling Class. Hyperion. ISBN 1401307558.

- Hoerr, John. 1997. We Can't Eat Prestige: The Women Who Organized Harvard. Temple University Press. ISBN 1-56639-535-6.

- Karabel, Jerome. 2006. The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. Mariner Books. ISBN 061877355X.

- Keller, Morton, and Phyllis Keller. 2007. Making Harvard Modern: The Rise of America's University. Oxford University Press. ISBN 019532515X.

- Lewis, Harry R. 2006. Excellence Without a Soul: How a Great University Forgot Education. PublicAffairs. ISBN 1586483935.

- Trumpbour, John (ed.). 1989. How Harvard Rules. Boston: South End Press. ISBN 0-89608-283-0.

External links

All links retrieved August 4, 2017.

| The Ivy League |

|---|

| Brown (Bears) • Columbia (Lions) • Cornell (Big Red) • Dartmouth (Big Green) • Harvard (Crimson) • Penn (Quakers) • Princeton (Tigers) • Yale (Bulldogs) |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.