Leonard Bernstein

| Leonard Bernstein | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Leonard Bernstein |

| Born | August 25, 1918, Lawrence, Massachusetts, United States |

| Died | October 14, 1990, New York City, New York |

| Occupation(s) | Composer, Conductor, Pianist |

| Notable instrument(s) | |

| Composer Conductor Piano | |

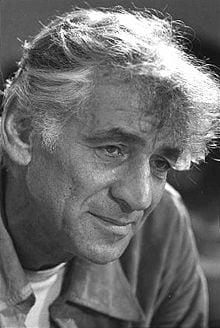

Leonard Bernstein (pronounced "Bern-styne")[1] (August 25, 1918 – October 14, 1990) was an American composer, pianist, and conductor. He was the first conductor born in the United States of America to receive world-wide acclaim, and is known for both his conducting of the New York Philharmonic, including the acclaimed Young People's Concerts series, and his multiple compositions, including West Side Story, Candide, and On The Town.

Bernstein was one of the first classical musicians to recognize the power of television as a vehicle to educate the masses, and he did so with an almost evangelical zeal. His commitment to teach and mentor young conductors at the Tanglewood Institute of Music remained his passion until his death in 1990.

Commenting on musical poetics and the "redicovery and reacceptance of tonality" in the Harvard Lectures given in 1973, he stated: "I believe that no matter how serial, or stochastic, or otherwise intellectualized music may be, it can always qualify as poetry as long as it is rooted in earth…and that the expressive distinctions among [new] idioms depend ultimately on the dignity and passion of the individual creative voice."

Biography

Childhood

Bernstein was born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1918, to a Jewish family from Rovno, Ukraine. His grandmother insisted his first name be Louis, but his parents always called him Leonard, as they liked that name better. He had his name changed to Leonard officially when he was fifteen. His father, Sam Bernstein, was a businessman, and initially opposed young Leonard's interest in music. Despite this, the elder Bernstein frequently took him to orchestral concerts. At a very young age, Bernstein heard a piano performance and was immediately captivated. He began learning to play, after his Aunt Clara gave the Bernsteins her piano when she was moving due to a divorce. As a child, Bernstein attended the Garrison and Boston Latin School. When his father heard about the piano lessons he refused to pay for them, so Bernstein taught young students himself and used that income to pay for his own piano lessons.

College

After graduation from Boston Latin School in 1935, Bernstein attended Harvard University, where he studied music with Walter Piston and was briefly associated with the Harvard Glee Club. After completing his studies at Harvard, he enrolled in the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he received the only grade of "A" that Fritz Reiner ever awarded in his class on conducting. During his time at Curtis, Bernstein also studied piano with Isabella Vengerova and Heinrich Gebhard.

Marriage and relationships

Bernstein married actress Felicia Montealegre Cohn on September 9, 1951.[2] They had three children, Jamie, Alexander, and Nina.[3] The Bernstein family lived in New York City and Fairfield, Connecticut, and maintained a close-knit atmosphere surrounded by extended family and friends. The family owned a house in Redding, Connecticut, which they sold in 1964.[4] Bernstein had a studio with a piano in each of his dwellings. The contents of his former studio at Fairfield, Connecticut are housed at the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music.[5]

Throughout his life, Bernstein had affairs with both men and women. In April 1943 he sought advice from Aaron Copland about living as a gay man in the public eye, suggesting he could resolve the dilemma by marrying his then "girlfriend ... my dentist's daughter,"[2] a notion he brought up again in a letter to David Oppenheim in July of that year. Adolph Green asked Bernstein about the status of this idea in a letter a few months later.[6] In a private letter written after their marriage, Felicia acknowledged her husband's sexual orientation. She wrote to him:

You are a homosexual and may never change — you don't admit to the possibility of a double life, but if your peace of mind, your health, your whole nervous system depend on a certain sexual pattern what can you do?[7][6]

In 1976, Bernstein left Felicia for a period to live in Northern California with Tom Cothran, a music scholar who had assisted him on research for the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures that Bernstein delivered at Harvard.[8] The following year, Felicia was diagnosed with lung cancer. Bernstein moved back in with her and cared for her until her death on June 16, 1978.[2]

He continued to have relationships with men until his death on October 14, 1990.[9]

Death

Bernstein announced his retirement from conducting on October 9, 1990.[10] He died five days later at the age of 72, in his New York apartment at The Dakota, of a heart attack brought on by mesothelioma.[11]

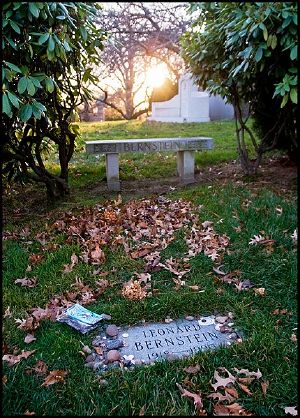

Bernstein is buried at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York,[12] next to his wife and with a copy of Mahler's Fifth Symphony lying across his heart.[13]

Career

Bernstein was highly regarded as a conductor of numerous concerts, featuring many of the world's leading orchestras, a composer of three symphonies, two operas, five musical theaters or musicals, and numerous other pieces; yet, he is especially known for composing the music for West Side Story. Additionally, he was a pianist, an educator, and the music director of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

In 1940, Bernstein began his study at the Boston Symphony Orchestra's summer institute, Tanglewood, under the orchestra's conductor, Serge Koussevitzky. He later became Koussevitzky's conducting assistant.[14]

On November 14, 1943, having recently been appointed assistant conductor of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, he made his conducting debut when Bruno Walter fell ill. He was an immediate success and became instantly famous, largely due to the fact that the concert had been broadcast to a national radio audience. The soloist on that historic day was Joseph Schuster, solo cellist of the New York Philharmonic, who played Richard Strauss's Don Quixote. Since Bernstein had never conducted the work before, Bruno Walter coached him on the piece prior to the concert. It is possible to hear this remarkable event thanks to a transcription recording made from the CBS radio broadcast that has since been issued on CDs.

After World War II, Bernstein conducted the New York City Symphony (along with Leopold Stokowski) and his career on the international stage began to flourish. In 1949, he conducted the world premiere of the Turangalîla-Symphonie by Olivier Messiaen. After Serge Koussevitzky died in 1951, Bernstein took the position of head of the orchestral and conducting departments at the Tanglewood Institute, an association that continued until his death in 1990.

In 1951, Bernstein conducted the Boston Symphony Orchestra in the world premiere of Charles Ives' Second Symphony. The composer, too old and frail to attend the concert, listened to the broadcast on the radio with his wife, Harmony. They both marveled at the enthusiastic reception of this symphony, which had actually been written between 1897 and 1901, and never performed prior to this occasion. Throughout his career, Bernstein did much to popularize the music of this uniquely American composer.

Bernstein was named Music Director of the New York Philharmonic in 1957 and began his tenure in that position in 1958, a post he held until 1969. He became a well-known figure in the United States through his series of fifty-three televised Young People's Concerts for CBS, which grew out of his Omnibus programs that CBS aired in the early 1950s.

His first Young People's Concert was televised only a few weeks after his tenure as principal conductor of the New York Philharmonic began. He became as famous for his educational work in these concerts as for his conducting. Some of his music lectures were released on audio recordings, with several of these albums winning Grammy awards. To this day, the Young People's Concerts series remains the longest running group of classical music programs ever shown on commercial television. They ran from 1958 to 1972, and are currently available in the DVD format.

In 1947, he conducted in Tel Aviv for the first time, beginning a life-long association with the people of Israel. In 1957, he conducted the inaugural concert of the Mann Auditorium in Tel Aviv and subsequently made many recordings there. In 1967, he conducted a concert on Mt. Scopus to commemorate the reunification of Jerusalem.

In 1959, he took the New York Philharmonic on a tour of Europe and the Soviet Union, portions of which were filmed by CBS. A major highlight of the tour was Bernstein's performance of Shostakovich's Fifth Symphony, in the presence of the composer, who came on stage upon the conclusion of the concert to congratulate Bernstein and the musicians of the New York Philharmonic. Upon retuning from their Russian tour, Bernstein and the Philharmonic recorded the symphony for Columbia Records at Symphony Hall in Boston.

In 1960, Bernstein began the first complete recordings of all nine completed symphonies of Gustav Mahler, with the blessings of the composer's widow, Alma. The success of these recordings, along with Bernstein's concert performances, greatly revived interest in Mahler, who had been music director of the New York Philharmonic from 1904 to 1907.

In 1966, he made his debut at the Vienna State Opera conducting Verdi's Falstaff (production by Luchino Visconti with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau as Falstaff). In 1970, he returned to the State Opera for Otto Schenk's production of Beethoven's Fidelio. In 1986, the State Opera had Bernstein conducting A Quiet Place. Bernstein's final farewell to the State Opera happened accidentally in 1989. Following a performance of Modest Mussorgsky's Khovanchina, he unexpectedly entered the stage and embraced conductor Claudio Abbado in front of a stunned, but cheering audience.

Beginning in 1970, Bernstein conducted the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, with which he re-recorded many of the pieces that he had previously recorded with the New York Philharmonic, including the complete symphonies of Beethoven, Mahler, Brahms, and Schumann.

Also in 1970, Bernstein wrote and narrated a ninety-minute program filmed on location in and around Vienna, featuring the Vienna Philharmonic and such artists as Placido Domingo (in his first television appearance as one of the soloists in Beethoven's Ninth). The program, first telecast in 1970, on Austrian and British television, and then on CBS on Christmas Eve 1971, was intended as a celebration of Ludwig van Beethoven's 200th birthday. The show made extensive use of the rehearsals and finished performance of the Otto Schenk production of "Fidelio." Originally entitled, Beethoven's Birthday: A Celebration in Vienna, the show, which won an Emmy, was telecast only once on U.S. non-cable television, and remained in CBS's vaults, until it resurfaced on A&E shortly after Bernstein's death under the new title Bernstein on Beethoven: A Celebration in Vienna. It was immediately issued on VHS under that title, and in 2005 was issued on DVD.

Bernstein was invited in 1973 to occupy the Charles Eliot Norton Chair at his alma mater, Harvard University, to deliver a series of six lectures on music. Borrowing the title from Charles Ives' work, he called the series, "The Unanswered Question." It is a set of interdisciplinary lectures in which he borrows terminology from contemporary linguistics (most notably, Noam Chomsky) to analyze and compare musical construction to language. The lecture survives both in book form and DVD.

In 1978, the Otto Schenk production of Fidelio, with Bernstein conducting (but featuring a different cast) was filmed by Unitel. Like the Bernstein on Beethoven program, it also was shown on A&E after his death and subsequently issued on VHS, though the video has since long been out-of-print, and there is no sign of a DVD reissue.

In 1979, Bernstein conducted the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra for the first and only time, in two charity concerts. The performance, of Mahler's Symphony No. 9 was broadcast on radio, and posthumously released on CD.

He received the Kennedy Center Honors award in 1980.

On PBS in the 1980s, he was the conductor and commentator for a special series on Beethoven's music, which featured the Vienna Philharmonic playing all nine Beethoven symphonies, several of his overtures, and the Missa Solemnis. Actor Maximilian Schell was also featured on the program, reading from Beethoven's letters.

On Christmas Day in 1989, Bernstein conducted Beethoven's Symphony No. 9 in East Berlin's Schauspielhaus (Playhouse) as part of a celebration of the fall of the Berlin Wall. The concert was broadcast live in more than twenty countries to an estimated audience of 100 million people. For the occasion, Bernstein reworded Friedrich Schiller's text of the Ode to Joy, substituting the word "freedom" (Freiheit) for "joy" (Freude): "I am sure we have Beethoven’s blessing," said Bernstein.[15]

Bernstein was a highly-regarded conductor among many musicians, in particular the members of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (of which he was an honorary member), the London Symphony Orchestra (whose members voted him Conductor Laureate), and the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, of which he was a regular guest conductor. He was considered especially accomplished with the works of Gustav Mahler, Aaron Copland, Johannes Brahms, Dmitri Shostakovich, George Gershwin (especially the Rhapsody in Blue and An American in Paris), and of course with the performances of his own works. Regrettably, he never conducted performances of Gershwin's Piano Concerto in F, nor did he ever conduct Porgy and Bess.

He conducted his final performance at Tanglewood on August 19, 1990, with the Boston Symphony performing Benjamin Britten's "Four Sea Interludes" and Ludwig van Beethoven's Seventh Symphony. The concert was later issued on CD by Deutsche Grammophon.

Recordings

Bernstein recorded extensively from the 1950s through the 1980s. Aside from a few early recordings for RCA Victor, Bernstein recorded primarily for Columbia, especially when he was music director of the New York Philharmonic. Many of these performances have been digitally remastered and reissued by Sony as part of the "Bernstein Century" series. When Columbia lost interest in American classical recordings, Bernstein signed an exclusive contract with Deutsche Grammophon that continued until his death.

Legacy

Leonard Bernstein was one of the most important conductors of the twentieth century.[16] He was held in high regard by musicians around the world, including the members of the New York Philharmonic, which he led for eleven seasons; the Vienna Philharmonic, where he received an honorary membership; the Boston Symphony Orchestra, which he conducted principally at Tanglewood for over 50 years; the London Symphony Orchestra, of which he was president; and the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, where he appeared regularly as their guest conductor.[17]

Bernstein was also an influential conducting teacher and mentor. During his many years at Tanglewood, Schleswig-Holstein and elsewhere, Bernstein directly influenced many young conductors, including Seiji Ozawa, Claudio Abbado, Lorin Maazel, Marin Alsop, Michael Tilson Thomas, James DePreist, Edo de Waart, Eiji Oue, JoAnn Falletta, Yutaka Sado, Maurice Peress, Carl St. Clair, John Mauceri, and Jaap van Zweden.[18]

Bernstein was an eclectic composer whose music fused elements of jazz, Jewish music, theatre music, and the work of earlier composers like Aaron Copland, Igor Stravinsky, Darius Milhaud, George Gershwin, and Marc Blitzstein. Some of Bernstein's works, especially his score for West Side Story, helped bridge the gap between classical and popular music.[19]

His shows West Side Story, On the Town, Wonderful Town and Candide continue to be performed regularly, and his symphonies and concert works are programmed by orchestras around the world. Since Bernstein's death, many of his works have been commercially recorded by various artists.

Bernstein sought to make music both intelligible and enjoyable to all. Through his educational efforts, including several books and the creation of two major international music festivals, Bernstein influenced several generations of young musicians.

In popular culture

- The Seinfeld character, Maestro, often refers to ideas that he learned from Leonard Bernstein.

- Bradley Cooper's drama film Maestro (2023) chronicles the relationship between Bernstein (played by Cooper) and his wife, Felicia Montealegre (played by Carey Mulligan). Produced by Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese, the film premiered at the Venice International Film Festival. As the Spotlight Gala feature of the 61st New York Film Festival, it was the first film presentation at the recently renovated David Geffen Hall in Lincoln Center.[20]

Awards and recognitions

- Grammy Award for Best Album for Children

- Grammy Award for Best Orchestral Performance

- Grammy Award for Best Choral Performance

- Grammy Award for Best Opera Recording

- Grammy Award for Best Classical Vocal Performance

- Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Soloist(s) Performance (with orchestra)

- Grammy Award for Best Classical Contemporary Composition

- Grammy Award for Best Classical Album

- Tony Award for Best Original Score

Principal works with first performance dates

Works for the theater

- Fancy Free (ballet), 1944

- On the Town (Musical), 1944

- Facsimile (ballet), 1946

- Peter Pan (songs, incidental music), 1950

- Trouble in Tahiti (opera in one act), 1952

- Wonderful Town (musical), 1953

- On the Waterfront (film score), 1954

- L'Alouette The Lark (incidental music), 1955

- Candide (operetta), 1956 (new libretto in 1973, operetta revised in 1989)

- West Side Story (musical), 1957

- The Firstborn (incidental music), 1958

- Mass (theatre piece for singers, players and dancers), 1971

- Dybbuk (ballet), 1974

- 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, 1976

- A Quiet Place (opera in two acts), 1983

- The Race to Urga (musical), 1987

Orchestral works for the concert hall

- Symphony No. 1, Jeremiah, 1942

- Fancy Free and Three Dance Variations from "Fancy Free," concert premiere 1946

- Three Dance Episodes from "On the Town," concert premiere 1947

- Symphony No. 2, The Age of Anxiety (after W. H. Auden), for Piano and Orchestra, 1949 (revised in 1965)

- Serenade (Plato dialogue) Plato's "Symposium" for Solo Violin, Strings, Harp and Percussion, 1954

- Prelude, Fugue and Riffs for Solo Clarinet and Jazz Ensemble, 1949

- Symphonic Suite from "On the Waterfront," 1955

- Symphonic Dances from "West Side Story," 1961

- Symphony No. 3, Kaddish, for Orchestra, Mixed Chorus, Boys' Choir, Speaker and Soprano Solo, 1963 (revised in 1977)

- Dybbuk, Suites No. 1 and 2 for Orchestra, concert premieres 1975

- Songfest: A Cycle of American Poems for Six Singers and Orchestra, 1977

- Three Meditations from "Mass" for Violoncello and Orchestra, 1977

- Slava!: A Political Overture for Orchestra, 1977

- Divertimento for Orchestra, 1980

- Halil, nocturne for Solo Flute, Piccolo, Alto Flute, Percussion, Harp and Strings, 1981

- Concerto for Orchestra, 1989 (Originally "Jubilee Games" from 1986, revised in 1989)

Choral music for church or synagogue

- Hashkiveinu for Solo Tenor, Mixed Chorus and Organ, 1945

- Missa Brevis for Mixed Chorus and Countertenor Solo, with Percussion, 1988

- Chichester Psalms for Countertenor, Mixed Chorus, Organ, Harp and Percussion, 1965

Chamber music

- Sonata for Clarinet and Piano (Bernstein)|Sonata for Clarinet and Piano, 1939

- Brass Music, 1959

- Dance Suite, 1988

Vocal music

- I Hate Music: A cycle of Five Kids Songs for Soprano and Piano, 1943

- La Bonne Cuisine: Four Recipes for Voice and Piano, 1948

- Arias and Barcarolles for Mezzo-Soprano, Baritone and Piano four-hands, 1988

- A Song Album, 1988

Other music

- Various piano pieces

- Other occasional works, written as gifts and other forms of memorial and tribute

- "The Skin of Our Teeth:" An aborted work from which Bernstein took material to use in his "Chichester Psalms"

Books

- Findings, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1982; New York: Anchor Books, 1993. ISBN 038542437X

- The Infinite Variety of Music, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1966; New York: Anchor Books, 1993. ISBN 0385424388

- The Joy of Music, Pompton Plains, New Jersey: Amadeus Press, 2004. ISBN 1574671049

- The Unanswered Question, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1976. ISBN 0674920007

Notes

- ↑ Fred Karlin, Listening to Movies: A Film Lover's Guide to Film Music (Cengage Learning, 2000, ISBN 0534263690).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Humphrey Burton, Leonard Bernstein (Doubleday, 1994, ISBN 978-0385423458).

- ↑ Joan Peyser, Bernstein, a Biography (New York: Beech Tree Books/William Morrow, 1987, ISBN 978-0688049188).

- ↑ Leonard Bernstein Sells House The New York Times (October 1, 1964). Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ↑ Bernstein Collection Jacobs School of Music. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Nigel Simeone (ed.), The Leonard Bernstein Letters (Yale University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0300179095).

- ↑ Felicia Bernstein to Leonard Bernstein, n.d. Library of Congress. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ↑ Mark Swed, Invoking Spirit of Bernstein Los Angeles Times (November 1, 1999). Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ↑ Jamie Bernstein, Famous Father Girl: A Memoir of Growing Up Bernstein (Harper, 2018, ISBN 978-0062641359).

- ↑ Allan Kozinn, Bernstein Retires From Performing, Citing Poor Health The New York Times (October 10, 1990). Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ↑ Donal Henahan, Leonard Bernstein, 72, Music's Monarch, Dies The New York Times (October 15, 1990). Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ↑ Scott Wilson, Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons (McFarland, 2016, ISBN 978-0786479924).

- ↑ Peter G. Davis, When Mahler Took Manhattan The New York Times (May 17, 2011). Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ↑ About Bernstein The Leonard Bernstein Office, Inc. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ↑ DVD + Blu-Ray: Leonard Bernstein – Ode to Freedom IMZ Consumer Newsletter (October, 2019). Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ↑ The 20 Greatest Conductors of All Time Classical Music. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ↑ Orchestras Conducted The Leonard Bernstein Office, Inc. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ↑ Paul R. Laird and Hsun Lin, Historical Dictionary of Leonard Bernstein (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019, ISBN 978-1538113448).

- ↑ Katherine Baber, Leonard Bernstein and the Language of Jazz (University of Illinois Press, 2019, ISBN 0252084160).

- ↑ Maestro Film at Lincoln Center (FLC). Retrieved December 20, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baber, Katherine. Leonard Bernstein and the Language of Jazz. University of Illinois Press, 2019. ISBN 0252084160

- Bernstein, Jamie. Famous Father Girl: A Memoir of Growing Up Bernstein. Harper, 2018. ISBN 978-0062641359

- Burton, Humphrey. Leonard Bernstein. Doubleday, 1994. ISBN 978-0385423458

- Gottlieb, Jack (ed.). Leonard Bernstein's Young People's Concerts. New York: Anchor Books, 1992. ISBN 0385424353

- Karlin, Fred. Listening to Movies: A Film Lover's Guide to Film Music. Cengage Learning, 2000. ISBN 0534263690

- Laird, Paul R., and Hsun Lin. Historical Dictionary of Leonard Bernstein. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019. ISBN 978-1538113448

- Peyser, Joan. Bernstein, a Biography. New York: Beech Tree Books/William Morrow, 1987. ISBN 978-0688049188

- Secrest, Meryle. Leonard Bernstein: A Life. New York: A.A.Knopf, 1994. ISBN 0679407316

- Simeone, Nigel (ed.) The Leonard Bernstein Letters. Yale University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0300179095

- Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons. McFarland, 2016. ISBN 978-0786479924

External links

All links retrieved March 11, 2025.

- Leonard Bernstein Office.

- Collection Leonard Bernstein The Library of Congress.

- Leonard Bernstein New York Philharmonic.

- Leonard Bernstein IMDb.

| Preceded by: Dmitri Mitropoulos |

New York Philharmonic 1958–1969 |

Succeeded by: George Szell |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.