Difference between revisions of "Fishery" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

[[Image:fishery.lobsterboat.arp.750pix.jpg|thumb|right|256px|A [[lobster]] boat unloading its catch in [[Ilfracombe]] harbour, [[North Devon]], [[England]].]] | [[Image:fishery.lobsterboat.arp.750pix.jpg|thumb|right|256px|A [[lobster]] boat unloading its catch in [[Ilfracombe]] harbour, [[North Devon]], [[England]].]] | ||

| − | A '''fishery''' (plural: fisheries) is an organized effort (industry, occupation) by humans to catch or process, | + | A '''fishery''' (plural: fisheries) is an organized effort (industry, occupation) by humans to catch and/or process, normally for sale, [[fish]], [[shellfish]], or other aquatic organisms. The activity of catching the aquatic species is called [[fishing]], and it is employed in the business of a fishery. Generally, a fishery exists for the purpose of providing human food, although other aims are possible, such as [[sport fishing|sport]] or [[fishing#Recreational fishing|recreational fishing]]), obtaining [[aquarium|ornamental fish]], or producing fish products such as [[fish oil]]. Industrial fisheries are fisheries where the catch is not intended for direct human consumption (Castro and Huber 2003). |

| − | The focus of a fishery may be fish, but the definition is expanded to include shellfish (aquatic | + | The focus of a fishery may be fish, but the definition is expanded to include shellfish (aquatic [[invertebrate]]s such as [[mollusk]]s, [[crustacean]]s, and [[echinoderm]]s), [[cephalopod]]s (mollusks, but sometimes not included in the definition of shellfish), and even [[amphibian]]s ([[frog]]s), [[reptile]]s ([[turtle]]s), and marine [[mammal]]s ([[seal]]s and [[whale]]s, although "whaling" is the term usually used instead of fishing). Among common mollusks that are the target of a fishery are [[clam]]s, [[mussel]]s, [[oyster]]s, and [[scallop]]s, and such edible cephalopods as [[squid]], [[octopus]], and [[cuttlefish]]. |

| + | Popular crustaceans are [[shrimp]], prawns, [[lobster]]s, [[crab]]s, and [[crayfish]], and representative echinoderms, which are popular in [[Asia]], are sea cucumbers and sea urchins. | ||

| − | The fishing effort is generally centered on either a particular | + | The fishing effort is generally centered on either a particular ecoregion or a particular species or type of fish or aquatic animal, and usually fisheries are differentiated by both criteria. Examples would be the [[salmon]] fishery of Alaska, the [[Atlantic cod|cod]] fishery off the Lofoten islands, or the [[tuna]] fishery of the Eastern Pacific. Most fisheries are marine, rather than freshwater; most marine fisheries are based near the coast. This is not only because harvesting from relatively shallow waters is easier than in the open ocean, but also because fish are much more abundant near the coastal shelf, due to coastal upwelling and the abundance of nutrients available there.[[Image:Vissersboot(01).jpg|thumb|right|250px|Fishing nets on a [[shrimp]] boat - [[Ostend]], Belgium]] |

| − | [[Image:Vissersboot(01).jpg|thumb|right|250px|Fishing nets on a [[shrimp]] boat - [[Ostend]], Belgium]] | ||

==Fisheries historically== | ==Fisheries historically== | ||

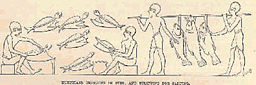

[[Image:Egyptian_fishery3.jpg|thumb|left|256px|[[Ancient_Egypt|Egyptians]] bringing in fish, and splitting for salting]] | [[Image:Egyptian_fishery3.jpg|thumb|left|256px|[[Ancient_Egypt|Egyptians]] bringing in fish, and splitting for salting]] | ||

Revision as of 18:43, 27 May 2007

A fishery (plural: fisheries) is an organized effort (industry, occupation) by humans to catch and/or process, normally for sale, fish, shellfish, or other aquatic organisms. The activity of catching the aquatic species is called fishing, and it is employed in the business of a fishery. Generally, a fishery exists for the purpose of providing human food, although other aims are possible, such as sport or recreational fishing), obtaining ornamental fish, or producing fish products such as fish oil. Industrial fisheries are fisheries where the catch is not intended for direct human consumption (Castro and Huber 2003).

The focus of a fishery may be fish, but the definition is expanded to include shellfish (aquatic invertebrates such as mollusks, crustaceans, and echinoderms), cephalopods (mollusks, but sometimes not included in the definition of shellfish), and even amphibians (frogs), reptiles (turtles), and marine mammals (seals and whales, although "whaling" is the term usually used instead of fishing). Among common mollusks that are the target of a fishery are clams, mussels, oysters, and scallops, and such edible cephalopods as squid, octopus, and cuttlefish. Popular crustaceans are shrimp, prawns, lobsters, crabs, and crayfish, and representative echinoderms, which are popular in Asia, are sea cucumbers and sea urchins.

The fishing effort is generally centered on either a particular ecoregion or a particular species or type of fish or aquatic animal, and usually fisheries are differentiated by both criteria. Examples would be the salmon fishery of Alaska, the cod fishery off the Lofoten islands, or the tuna fishery of the Eastern Pacific. Most fisheries are marine, rather than freshwater; most marine fisheries are based near the coast. This is not only because harvesting from relatively shallow waters is easier than in the open ocean, but also because fish are much more abundant near the coastal shelf, due to coastal upwelling and the abundance of nutrients available there.

Fisheries historically

One of the world’s longest lasting trade histories is the trade of dry cod from the Lofoten area to the southern parts of Europe, Italy, Spain and Portugal. The trade in cod started during the Viking period or before, has been going on for more than 1000 years and is still important.

In India, the Pandyas, a classical Dravidian Tamil kingdom, were known for the pearl fishery as early as the 1st century B.C.E. Their seaport Tuticorin was known for deep sea pearl fishing. The paravas, a Tamil caste centred in Tuticorin, developed a rich community because of their pearl trade, navigation knowledge and fisheries.

Fisheries in the present day

Today, fisheries are estimated to provide 16% of the world population's protein, and that figure is considerably elevated in some developing nations and in regions that depend heavily on the sea.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, total world capture fisheries production in 2000 was 86 million tons (FAO 2002). The top producing countries were, in order, the People's Republic of China (excluding Hong Kong and Taiwan), Peru, Japan, the United States, Chile, Indonesia, Russia, India, Thailand, Norway and Iceland. Those countries accounted for more than half of the world's production; China alone accounted for a third of the world's production. Of that production, over 90% was marine and less than 10% was inland.

There are large and important fisheries worldwide for various species of fish, mollusks and crustaceans. However, a very small number of species support the majority of the world’s fisheries. Some of these species are herring, cod, anchovy, tuna, flounder, mullet, squid, shrimp, salmon, crab, lobster, oyster and scallops. All except these last four provided a worldwide catch of well over a million tonnes in 1999, with herring and sardines together providing a catch of over 22 million metric tons in 1999. Many other species as well are fished in smaller numbers.

Methods

A fishery can consist of one man with a small boat hand-casting nets, to a huge fleet of trawlers processing tons of fish per day. Some techniques are trawling, seining, driftnetting, handlining, longlining, gillnetting, dragger, tile, and diving.

Fisheries and communities

For communities, fisheries provide not only a source of food and work but also a community and cultural identity. [1]

This shows up in art, literature, and traditions.

Fisheries science

Fisheries science is the academic discipline of managing and understanding fisheries. It draws on the disciplines of biology, ecology, oceanography, economics and management to attempt to provide an integrated picture of fisheries. It is typically taught in a university setting, and can be the focus of an undergraduate, master's or Ph.D. program. In some cases new disciplines have emerged, as in the case of bioeconomics. A few universities also offer fully integrated programs in fisheries science.

See also: International Council for the Exploration of the Sea

Important issues and topics in fisheries

There are many environmental issues surrounding fishing. These can be classed into issues that involve the availability of fish to be caught, such as overfishing, sustainable fisheries, and fisheries management; and issues surrounding the impact of fishing on the environment, such as by-catch. These fishery conservation issues are generally considered part of marine conservation, and many of these issues are addressed in fisheries science programs. There is an apparent and growing disparity between the availability of fish to be caught and humanity’s desire to catch them, a problem that is exacerbated by the rapidly growing world population. As with some other environmental issues, often the people engaged in the activity of fishing – the fishers – and the scientists who study fisheries science, who are often acting as fishery managers, are in conflict with each other, as the dictates of economics mean that fishers have to keep fishing for their livelihood, but the dictates of sustainable science mean that some fisheries must close or reduce to protect the health of the population of the fish themselves. It is starting to be realized, however, that these two camps must work together to ensure fishery health through the 21st century and beyond.

The cover story of the May 15, 2003 issue of the science journal Nature – with Dr. Ransom A. Myers, an internationally prominent fisheries biologist (Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada) as the lead author – was devoted to a summary of the scientific information. The story asserted that, as compared with 1950 levels, only a remnant (in some instances, as little as 10%) of all large ocean-fish stocks are left in the seas. These large ocean fish are the species at the top of the food chains (e.g., tuna, cod, among others). However, this article was subsequently criticized as being fundamentally flawed, although much debate still exists (Walters 2003; Hampton et al. 2005; Maunder et al. 2006; Polacheck 2006;Sibert et al. 2006) and the majority of fisheries scientists now consider the results irrelevant with respect to large pelagics (the open seas) (http://www.soest.hawaii.edu/PFRP/large_pelagics/large_pelagic_predators.html).

In mid October 2006, U.S. President Bush joined other world leaders calling for a moratorium on deep-sea trawling, a practice shown to often have harmful effects on sea habitat, hence on fish populations.

The journal Science published a four-year study in November 2006, which predicted that, at prevailing trends, the world would run out of wild-caught seafood in 2048. The scientists stated that the decline was a result of overfishing, pollution and other environmental factors that were reducing the population of fisheries at the same time as their ecosystems were being degraded. Yet again the analysis has met criticism as being fundamentally flawed, and many fishery management officials, industry representatives and scientists challenge the findings, although the debate continues. Many countries, such as Tonga, the United States and New Zealand, and international management bodies have taken steps to appropriately manage marine resources.[1][2]

For further information

The literature on fisheries—both scientific and popular—is vast. The literature is subdivided into dozens of topics, from fishing gear design, to the impact of fish biology and oceanography on fisheries, to how to most effectively manage fisheries. Some well known journals about fisheries are Fisheries, Fisheries Oceanography, Fishery Bulletin, and The Canadian Journal of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences. In addition, many countries have their own regional journals.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Cited

- ↑ Worm, Boris, et al. (2006-11-03). Impacts of Biodiversity Loss on Ocean Ecosystem Services. Science 314 (5800): 787 - 790.

- ↑ Juliet Eilperin (2 November 2006). "Seafood Population Depleted by 2048, Study Finds". The Washington Post.

General

- Castro, P. and M. Huber. (2003). Marine Biology. 4th ed. Boston: McGraw Hill.

- Hampton, J., Sibert, J. R., Kleiber, P., Maunder, M. N., and Harley, S. J. 2005. Changes in abundance of large pelagic predators in the Pacific Ocean. Nature, 434: E2-E3.

- Maunder, M.N., Sibert, J.R. Fonteneau, A., Hampton, J., Kleiber, P., and Harley, S. 2006. Interpreting catch-per-unit-of-effort data to asses the status of individual stocks and communities. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 63: 1373-1385.

- Myers, Ransom and Boris Worm. (May 15, 2003). "Rapid worldwide depletion of predatory fish communities," Nature, Vol 423. London: Nature Publishing.

- Polacheck, T. 2006. "Tuna longline catch rates in the Indian Ocean: did industrial fishing result in a 90% rapid decline in the abundance of large predatory species?" Marine Policy, 30: 470-482.

- FAO Fisheries Department. (2002). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Sibert, et al. 2006. Biomass, Size, and Trophic Status of Top Predators in the Pacific Ocean Science 314: 1773

- Walters, C. J. 2003. Folly and fantasy in the analysis of spatial catch rate data. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 60: 1433-1436.

- Pelagic Fisheries Research Program

- International Collective in Support of Fishworkers website

- United Nations conference in criticism of deep-sea trawling

- Bush backs international deep-sea trawling moratorium

- Re-interpreting the Fisheries Crisis seminar by Prof. Ray Hilborn

See also

- Age class structure

- Agriculture

- Aquaculture

- Conservation

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- Earthwatch

- Ecosystem

- Environmental effects of fishing

- Fish

- Fish farming

- Fish (food)

- Fishing

- Fishing industry

- GLOBEC

- Hatcheries

- International Council for the Exploration of the Sea

- Marine conservation

- Marine ecosystem

- Marine Protected Area

- Maximum sustainable yield

- National Coalition for Marine Conservation

- Oceanography

- Project AWARE

- World Ocean Day

External links

- Crisis in Ocean Fisheries - United Nations: Oceans and Coastal Areas (UNEP)

- Fishery Information from the Coastal Ocean Institute, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

- FAO Fisheries Department and its SOFIA report

- State of World Fisheries – A summary for non-specialists of the above FAO report by GreenFacts.

- The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES)

- NOAA Fisheries (National Marine Fisheries Service, United States)

- The American Fisheries Society

- The National Fisheries Institute – The Fish and Seafood Trade Association

- The International Institute of Fisheries Economics and Trade (IIFET)

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- Read Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding Fisheries

- Dynamic Changes in Marine Ecosystems: Fishing, Food Webs, and Future Options (2006), U.S. National Academy of Sciences

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections — Freshwater and Marine Image Bank Commercial Fisheries and Traditional Fisheries Images of Fisheries.

- The Grand Banks cod stocks collapse Fishery crisis webpage

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.