Cumin

- "Geerah" redirects here.

| Cumin | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Cuminum cyminum L.[1] |

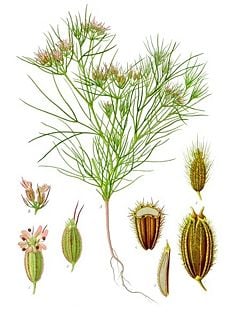

Cumin (Cuminum cyminum) (sometimes spelled cummin) is a flowering plant in the family Apiaceae, native from the east Mediterranean to East India.

Traditionally, it was pronounced CUM-in (kŭm'ĭn), but COO-min (kōō'mĭn) or CUE-min (kyōō'mĭn) are increasingly common.

It is a herbaceous annual plant, with a slender branched stem 20-30 cm tall. The leaves are 5-10 cm long, pinnate or bipinnate, thread-like leaflets. The flowers are small, white or pink, and borne in umbels. The fruit is a laterall fusiform or ovoid achene 4-5 mm long, containing a single seed. Cumin seeds are similar to fennel seeds in appearance, but are smaller and darker in colour.

Cultivation and uses

Cumin seeds are used as a spice for their distinctive aroma, popular in North African, Middle Eastern, Western Chinese, Indian, Cuban and Mexican cuisine.

Cumin's distinctive flavour and strong, warm aroma is due to its essential oil content. Its main constituent and important aroma compound is cuminaldehyde (4-isopropylbenzaldehyde). Important aroma compounds of toasted cumin are the substituted pyrazines, 2-ethoxy-3-isopropylpyrazine, 2-methoxy-3-sec-butylpyrazine, and 2-methoxy-3-methylpyrazine.

Today, cumin is identified with Indian, Mexican and Cuban cuisine. It is used as an ingredient of curry powder. Cumin can be found in some Dutch cheeses like Leyden cheese, and in some traditional breads from France. It is also commonly used in traditional Brazilian cuisine. In herbal medicine, cumin is classified as stimulant, carminative, and antimicrobial.

Cumin can be used to season many dishes, as it draws out their natural sweetnesses. It is traditionally added to curries, enchiladas, tacos, and other Middle-eastern, Indian, Cuban and Mexican-style foods. It can also be added to salsa to give it extra flavour. Cumin has also been used on meat in addition to other common seasonings. The spice is a familiar taste in Tex-Mex dishes and is extensively used in the cuisines of the Indian subcontinent. Cumin was also used heavily in ancient Roman cuisine.

Cultivation of cumin requires a long, hot summer of 3-4 months, with daytime temperatures around 30°C (86°F); it is drought tolerant, and is mostly grown in mediterranean climates. It is grown from seed sown in spring, and needs a fertile, well-drained soil.

Description

Cumin is the dried seed of the herb Cuminum cyminum, a member of the parsley family. The cumin plant grows to 30-50 cm (1-2 ft) tall and is harvested by hand.

Uses

The flavour of cumin plays a major role in Cuban, Mexican, Thai, Vietnamese, Turkish, Afgan and Indian cuisines. Cumin is a critical ingredient of chili powder, and is found in achiote blends, adobos, sofrito, garam masala, curry powder, and bahaarat.

Cumin seeds are often ground up before being added to dishes.

Cumin seeds are also often toasted by being heated in an ungreased frying pan to help release their essential oils.

Origins

Historically, Iran has been the principal supplier of cumin, but currently the major sources are India, Sri Lanka, Syria, Pakistan, and Turkey.

Folklore

Superstition during the Middle Ages cited that cumin kept chickens and lovers from wandering. It was also believed that a happy life awaited the bride and groom who carried cumin seed throughout the wedding ceremony. Cumin is also said to help in treatment of the common cold, when added to hot milk and consumed.

Cumin tea is also believed to help induce labor in a woman who has gone post-dates with her pregnancy.

In Sri Lanka, toasting cumin seeds and then boiling them in water makes a tea used to soothe acute stomach problems.

History

Cumin has been in use since ancient times. Seeds, excavated at the Syrian site Tell ed-Der, have been dated to the second millennium B.C.E. They have also been reported from several New Kingdom levels of ancient Egyptian archaeological sites.[2]

Originally cultivated in Iran and Mediterranean region, cumin is mentioned in the Bible in both the Old Testament (Isaiah 28:27) and the New Testament (Matthew 23:23). It was also known in ancient Greece and Rome. The Greeks kept cumin at the dining table in its own container (much as pepper is frequently kept today), and this practice continues in Morocco. Cumin fell out of favour in Europe except in Spain and Malta during the Middle Ages. It was introduced to the Americas by Spanish colonists.

Since returned to favour in parts of Europe, today it is mostly grown in Iran, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Morocco, Egypt, India, Syria, Mexico, and Chile.

Etymology

The English "cumin" came French "cumin" that was borrowed indirectly from Arabic "Kammon كمون" through Spanish "comino" during the Arab rule in Spain in the 15th century. This makes sense because this spice is native to Syria (Arabic speaking country)where cumin thrives in its hot and arid lands. Cumin seeds has been found in some ancient Syrian archeological sites. The word found its way from Syria to neighbroing Turkey and nearby Greece most likely before it found its way to Spain, but like many other Arabic words in the English language, cumin was acquired through Western Europe rather than the Greece route. Some theories suggest that the word is derived from the Latin cuminum and Greek κύμινον, however, this is unlikely. The Greek term itself has been borrowed from a Arabic. Forms of this word are attested in several ancient Semitic languages, including kamūnu in Akkadian[1]. The ultimate source is a native Syrian language that could be the Sumerian word gamun [2].

A folk etymology connects the word with the Persian city Kerman, where, the story goes, most of ancient Persia's cumin was produced. For the Persians the expression "carrying cumin to Kerman" has the same meaning as the English language phrase "carrying coals to Newcastle". Kerman, locally called "Kermun", would have become "Kumun" and finally "cumin" in the European languages.

In India and Pakistan, cumin is known as jeera or jira or sometimes zira; in Iran and Central Asia, cumin is known as zira; in Turkey, cumin is known as kimyon;in northwestern China, cumin is known as ziran. In Arabic, it is known as al-kamuwn (ال). Cumin is called kemun in Ethiopian, and is one of the ingredients in the spice mix berbere.

Confusion with other spices

Cumin is hotter to the taste, lighter in colour, and larger than caraway (Carum carvi), another umbelliferous spice that is sometimes confused with it. Many European languages do not distinguish clearly between the two. For example, in Czech caraway is called 'kmín' while cumin is called 'římský kmín' or "Roman caraway." Some older cookbooks erroneously name ground coriander as the same spice as ground cumin. [3]

The distantly related Bunium persicum and the unrelated Nigella sativa are both sometimes called black cumin (q.v.).

| Cumin seeds Nutritional value per 100 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy 370 kcal 1570 kJ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Percentages are relative to US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient database | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Images

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Cuminum cyminum information from NPGS/GRIN. www.ars-grin.gov. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ↑ Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf, Domestication of plants in the Old World, third edition (Oxford: University Press, 2000), p. 206

- ↑ Growingtaste.com

External links

| Herbs and spices | |

|---|---|

| Herbs | Angelica • Basil • Basil, holy • Basil, Thai • Bay leaf • Boldo • Borage • Cannabis • Chervil • Chives • Coriander leaf (cilantro) • Curry leaf • Dill • Epazote • Eryngium foetidum (long coriander) • Hoja santa • Houttuynia cordata (giấp cá) • Hyssop • Lavender • Lemon balm • Lemon grass • Lemon verbena • Limnophila aromatica (rice paddy herb) • Lovage • Marjoram • Mint • Mitsuba • Oregano • Parsley • Perilla (shiso) • Rosemary • Rue • Sage • Savory • Sorrel • Stevia • Tarragon • Thyme • Vietnamese coriander (rau răm) • Woodruff |

| Spices | African pepper • Ajwain (bishop's weed) • Aleppo pepper • Allspice • Amchur (mango powder) • Anise • Aromatic ginger • Asafoetida • Camphor • Caraway • Cardamom • Cardamom, black • Cassia • Cayenne pepper • Celery seed • Chili • Cinnamon • Clove • Coriander seed • Cubeb • Cumin • Cumin, black • Dill seed • Fennel • Fenugreek • Fingerroot (krachai) • Galangal, greater • Galangal, lesser • Garlic • Ginger • Grains of Paradise • Horseradish • Juniper berry • Liquorice • Mace • Mahlab • Malabathrum (tejpat) • Mustard, black • Mustard, brown • Mustard, white • Nasturtium • Nigella (kalonji) • Nutmeg • Paprika • Pepper, black • Pepper, green • Pepper, long • Pepper, pink, Brazilian • Pepper, pink, Peruvian • Pepper, white • Pomegranate seed (anardana) • Poppy seed • Saffron • Sarsaparilla • Sassafras • Sesame • Sichuan pepper (huājiāo, sansho) • Star anise • Sumac • Tasmanian pepper • Tamarind • Turmeric • Wasabi • Zedoary |