Difference between revisions of "Cold War" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (41 intermediate revisions by 14 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Edboard}}{{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}} |

| − | + | [[File:Berlinermauer.jpg|thumb|250 px|Photograph of the Berlin Wall taken from the West side. The Wall was built in 1961 to prevent East Germans from fleeing and to stop an economically disastrous drain of workers. It was a symbol of the Cold War and its fall in 1989 marked the approaching end of the war.]] | |

| − | + | The '''Cold War''' was the protracted [[ideology|ideological]], [[geopolitics|geopolitical]], and [[economics|economic]] struggle that emerged after [[World War II]] between the global superpowers of the [[Soviet Union]] and the [[United States]], supported by their military alliance partners. It lasted from the end of World War II until the period preceding the demise of the Soviet Union on December 25, 1991. | |

| − | The '''Cold War''' was the | ||

| − | The global | + | The global confrontation between the West and communism was popularly termed ''The Cold War'' because direct hostilities never occurred between the United States and the Soviet Union. Instead, the "war" took the form of an arms race involving nuclear and conventional weapons, military alliances, economic warfare and targeted trade [[embargo]]s, [[propaganda]], and disinformation, [[espionage]] and counterespionage, proxy wars in the developing world that garnered superpower support for opposing sides within [[civil war]]s. The [[Cuban Missile Crisis]] of 1962 was the most important direct confrontation, together with a series of confrontations over the Berlin Blockade and the [[Berlin Wall]]. The major civil wars polarized along Cold War lines were the Greek Civil War, [[Korean War]], [[Vietnam War]], the war in [[Soviet-Afghan War|Afghanistan]], as well as the conflicts in [[Angola]], [[El Salvador]], and [[Nicaragua]]. |

| − | + | During the Cold War there was concern that it would escalate into a full nuclear exchange with hundreds of millions killed. Both sides developed a deterrence policy that prevented problems from escalating beyond limited localities. [[Nuclear weapon|Nuclear weapons]] were never used in the Cold War. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | The Cold War cycled through a series of high and low tension years (the latter called [[detente]]). It ended in the period between 1988 and 1991 with the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, the emergence of [[Solidarity]], the fall of the Berlin Wall, the dissolution of the [[Warsaw Pact]] and the demise of the Soviet Union itself. | ||

| − | + | Historians continue to debate the reasons for the Soviet collapse in the 1980s. Some fear that as one super-power emerges without the limitations imposed by a rival, the world may become a less secure place. Many people, however, see the end of the Cold War as representing the triumph of [[democracy]] and freedom over totalitarian rule, state-mandated atheism, and a repressive communist system that claimed the lives of millions. While equal blame for Cold War tensions is often attributed both to the United States and the Soviet Union, it is evident that the Soviet Union had an ideological focus that found the Western democratic and free market systems inherently oppressive and espoused their overthrow, beginning with the [[Communist Manifesto]] of 1848. | |

| + | |||

| + | ==Origin of the Term "Cold War"== | ||

| + | {{readout||right|250px|[[Walter Lippmann]] was the first to bring the phrase "Cold War" into common use with the publication of his 1947 book of the same name}} | ||

| + | The origins of the term "Cold War" are debated. The term was used hypothetically by [[George Orwell]] in 1945, though not in reference to the struggle between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, which had not yet been initiated. American politician Bernard Baruch began using the term in April 1947 but it first came into general use in September 1947 when journalist [[Walter Lippmann]] published a book on U.S.-Soviet tensions entitled ''The Cold War''. | ||

==Historical overview== | ==Historical overview== | ||

===Origins=== | ===Origins=== | ||

| − | + | Tensions between the [[Soviet Union]] and the [[United States]] resumed following the conclusion of the [[World War II|Second World War]] in August 1945. As the war came to a close, the Soviets laid claim to much of Eastern Europe and the Northern half of Korea. They also attempted to occupy Japanese northernmost island of [[Hokkaido]] and lent logistic and military support to [[Mao Zedong]] in his efforts to overthrow the Chinese Nationalist forces. Tensions between the Soviet Union and the Western powers escalated between 1945–1947, especially when in Potsdam, Yalta, and Tehran, [[Stalin]]'s plans to consolidate Soviet control of Central and Eastern Europe became manifestly clear. On March 5, 1946 [[Winston Churchill]] delivered his landmark speech at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri lamenting that an "iron curtain" had descended on Eastern Europe. | |

| − | |||

| − | Tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States resumed | ||

| − | Historians | + | Historians interpret the Soviet Union's Cold War intentions in two different manners. One emphasizes the primacy of [[communism|communist]] ideology and communism's foundational intent, as outlined in the [[Communist Manifesto]], to establish global hegemony. The other interpretation, advocated notably by Richard M. Nixon, emphasized the historical goals of the Russian state, specifically hegemony over Eastern Europe, access to warm water seaports, the defense of other Slavic peoples, and the view of Russia as "the Third Rome." The roots of the ideological clashes can be seen in Marx's and Engels' writings and in the writings of [[Vladimir Lenin]] who succeeded in building communism into a political reality through the Bolshevik seizure of power in the [[Russian Revolution of 1917]]. Walter LaFeber stresses Russia's historic interests, going back to the Czarist years when the [[United States]] and Russia became rivals. From 1933 to 1939 the United States and the Soviet Union experienced détente but relations were not friendly. After the USSR and [[Germany]] became enemies in 1941, [[Franklin Delano Roosevelt]] made a personal commitment to help the Soviets, although the U. S. Congress never voted to approve any sort of alliance and the wartime cooperation was never especially friendly. For example, [[Josef Stalin]] was reluctant to allow American forces to use Soviet bases. Cooperation became increasingly strained by February 1945 at the [[Yalta Conference]], as it was becoming clear that Stalin intended to spread communism to Eastern Europe—and then, perhaps—to [[France]] and [[Italy]]. |

| − | Some historians such as | + | Some historians such as William Appleman Williams also cite American economic expansionism as one of the roots of the Cold War. These historians use the [[Marshall Plan]] and its terms and conditions as evidence to back up their claims. |

| − | These geopolitical and ideological rivalries were accompanied by a third factor that had just emerged from | + | These geopolitical and ideological rivalries were accompanied by a third factor that had just emerged from World War II as a new problem in world affairs: the problem of effective international control of [[nuclear energy]]. In 1946 the Soviet Union rejected a United States proposal for such control, which had been formulated by Bernard Baruch on the basis of an earlier report authored by Dean Acheson and David Lilienthal, with the objection that such an agreement would undermine the principle of national sovereignty. The end of the Cold War did not resolve the problem of international control of nuclear energy, and it has re-emerged as a factor in the beginning of the Long War (or the war on global terror) declared by the United States in 2006 as its official military doctrine. |

===Global Realignments=== | ===Global Realignments=== | ||

| − | + | This period began the Cold War in 1947 and continued until the change in leadership for both superpowers in 1953—from Presidents [[Harry S. Truman]] to [[Dwight D. Eisenhower]] in the United States, and from [[Josef Stalin]] to [[Nikita Khrushchev]] in the Soviet Union. | |

| − | |||

| − | This period began the Cold War in 1947 and continued until the change in leadership for both superpowers in 1953 | ||

| − | + | Notable events include the [[Truman Doctrine]], the Marshall Plan, the [[Berlin Blockade]] and [[Berlin Airlift]], the Soviet Union's detonation of its first [[atomic bomb]], the formation of [[NATO]] in 1949 and the [[Warsaw Pact]] in 1955, the formation of [[German Democratic Republic|East]] and [[West Germany]], the Stalin Note for German reunification of 1952 superpower disengagement from Central Europe, the Chinese Civil War and the [[Korean War]]. | |

| − | The American Marshall Plan intended to rebuild the European economy after the devastation | + | The American [[Marshall Plan]] intended to rebuild the European economy after the devastation incurred by the Second World War in order to thwart the political appeal of the radical left. For Western Europe, economic aid ended the dollar shortage, stimulated private investment for postwar reconstruction and, most importantly, introduced new managerial techniques. For the U.S., the plan rejected the [[isolationism]] of the 1920s and integrated the North American and Western European economies. The Truman Doctrine refers to the decision to support [[Greece]] and [[Turkey]] in the event of Soviet incursion, following notice from [[United Kingdom|Britain]] that she was no longer able to aid Greece in its civil war against communist activists. |

| + | The Berlin blockade took place between June 1948 and July 1949, when the Soviets, in an effort to obtain more post-World War II concessions, prevented overland access to the allied zones in [[Berlin]]. Thus, personnel and supplies were lifted in by air. The Stalin Note was a plan for the reunification of Germany on the condition that it became a neutral state and that all Western troops be withdrawn. | ||

===Escalation and Crisis=== | ===Escalation and Crisis=== | ||

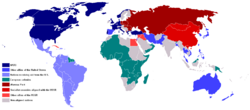

| − | + | [[Image:Cold War Map 1959.png|thumb|250px|Two opposing geopolitical blocs had developed by 1959 as a result of the Cold War; consult the legend on the map for more details]] | |

| − | + | A period of escalation and crisis existed between the change in leadership for both superpowers from 1953—with [[Josef Stalin]]’s sudden death and the American presidential election of 1952—until the resolution of the [[Cuban Missile Crisis]] in 1962. | |

| − | [[Image:Cold War Map 1959.png|thumb|250px|Two opposing geopolitical blocs had developed by 1959 as a result of the Cold War | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Events included the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, the erection of the [[Berlin Wall]] in 1961, the | + | Events included the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, the erection of the [[Berlin Wall]] in 1961, the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 and the [[Prague Spring]] in 1968. During the [[Cuban Missile Crisis]], in particular, the world was closest to a third (nuclear) world war. The Prague Spring was a brief period of hope, when the government of [[Alexander Dubček]] (1921–1992) started a process of liberalization, which ended abruptly when the Russian Soviets invaded [[Czechoslovakia]]. |

===Thaw and Détente, 1962-1979=== | ===Thaw and Détente, 1962-1979=== | ||

| − | + | The Détente period of the Cold War was marked by mediation and comparative peace. At its most reconciliatory, German Chancellor [[Willy Brandt]] forwarded the foreign policy of ''Ostpolitik'' during his tenure in the Federal Republic of Germany. Translated literally as "eastern politics," Egon Bahr, its architect and advisor to Brandt, framed this policy as "change through rapprochement." | |

| − | |||

| − | The | ||

| − | These initiatives led to the | + | These initiatives led to the Warsaw Treaty between [[Poland]] and [[West Germany]] on December 7, 1970; the Quadripartite or Four-Powers Agreement between the [[Soviet Union]], [[United States]], [[France]] and [[United Kingdom|Great Britain]] on September 3, 1971; and a few east-west German agreements including the Basic Treaty of December 21, 1972. |

| − | Limitations to reconciliation did exist, | + | Limitations to reconciliation did exist, evidenced by the deposition of Walter Ulbricht by Erich Honecker as East German General Secretary on May 3, 1971. |

===Second Cold War=== | ===Second Cold War=== | ||

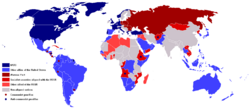

| − | + | [[Image:Cold War Map 1980.png|thumb|250px|The diversified state of the Cold War relations in 1980;. consult the legend on the map for more details]] | |

| − | [[Image:Cold War Map 1980.png|thumb|250px|The diversified state of the Cold War relations in 1980. | + | The period between the Soviet invasion of [[Afghanistan]] in 1979 and the rise of [[Mikhail Gorbachev]] as Soviet leader in 1985 was characterized by a marked "freeze" in relations between the superpowers after the "thaw" of the Détente period of the 1970s. As a result of this reintensification, the period is sometimes referred to as the "Second Cold War." |

| − | The | + | The [[Soviet-Afghan War|Soviet invasion of Afghanistan]] in 1979 in support of an embryonic communist regime in that country led to international outcries and the widespread boycotting of the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games by many Western countries in protest at Soviet actions. The Soviet invasion led to a protracted conflict, which involved [[Pakistan]]—an erstwhile U.S. ally—in locked horns with the Soviet military might for over 12 years. |

| − | + | Worried by Soviet deployment of nuclear SS-20 missiles (commenced in 1977), [[NATO]] allies agreed in 1979 to continued [[Strategic Arms Limitation Talks]] to constrain the number of nuclear missiles for battlefield targets, while threatening to deploy some five hundred cruise missiles and ''MGM-31 Pershing II'' missiles in West Germany and the [[Netherlands]] if negotiations were unsuccessful. The negotiations failed, as expected. The planned deployment of the ''Pershing II'' met intense and widespread opposition from public opinion across Europe, which became the site of the largest demonstrations ever seen in several countries. ''Pershing II'' missiles were deployed in Europe beginning in January 1984, and were withdrawn beginning in October 1988. | |

| − | + | The "new conservatives" or "neoconservatives" rebelled against both the [[Richard Nixon]]-era policies and the similar position of [[Jimmy Carter]] toward the Soviet Union. Many clustered around hawkish Senator Henry "Scoop" Jackson, a Democrat, and pressured President Carter into a more confrontational stance. Eventually they aligned themselves with [[Ronald Reagan]] and the conservative wing of the Republicans, who promised to end Soviet expansionism. | |

| − | The | + | The elections, first of [[Margaret Thatcher]] as British prime minister in 1979, followed by that of Ronald Reagan to the American presidency in 1980, saw the elevation of two hard-line warriors to the leadership of the Western Bloc. |

| − | + | Other events included the [[Strategic Defense Initiative]] and the Solidarity Movement in [[Poland]]. | |

| − | + | ==="End" of the Cold War=== | |

| + | [[Image:Cold War border changes.png|thumb|Changes in borders in Europe and Central Asia with the end of the Cold War; some 23 new countries were formed in the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s demise]] | ||

| + | This period began at the rise of [[Mikhail Gorbachev]] as Soviet leader in 1985 and continued until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. | ||

| − | + | Events included the [[Chernobyl]] accident in 1986, and the Autumn of Nations—when one by one, communist regimes collapsed. This includes the famous [[Berlin Wall|fall of the Berlin Wall]] in 1989), the Soviet coup attempt of 1991 and collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | Other noteworthy events include the implementation of the policies of [[glasnost]] and [[perestroika]], public discontent over the Soviet Union's war in [[Afghanistan]], and the socio-political effects of the Chernobyl nuclear plant accident in 1986. East-West tensions eased rapidly after the rise of [[Mikhail Gorbachev]]. After the deaths of three elderly Soviet leaders in quick succession beginning with [[Leonoid Breshnev]] in 1982, the Politburo elected Gorbachev Soviet Communist Party chief in 1985, marking the rise of a new generation of leadership. Under Gorbachev, relatively young reform-oriented technocrats rapidly consolidated power, providing new momentum for political and economic liberalization and the impetus for cultivating warmer relations and trade with the West. |

| − | + | Meanwhile, in his second term, [[Ronald Reagan]] surprised the neoconservatives by meeting with Gorbachev in [[Geneva]], [[Switzerland]] in 1985 and Reykjavík, [[Iceland]] in 1986. The latter meeting focused on continued discussions around scaling back the intermediate missile arsenals in Europe. The talks were unsuccessful. Afterwards, Soviet policymakers increasingly accepted Reagan's administration warnings that the U.S. would make the arms race an increasing financial burden for the USSR. The twin burdens of the Cold War arms race on one hand and the provision of large sums of foreign and military aid, upon which the socialist allies had grown to expect, left Gorbachev's efforts to boost production of consumer goods and reform the stagnating economy in an extremely precarious state. The result was a dual approach of cooperation with the west and economic restructuring (perestroika) and democratization (glasnost) domestically, which eventually made it impossible for Gorbachev to reassert central control over Warsaw Pact member states. | |

| − | + | Thus, beginning in 1989 Eastern Europe's communist governments toppled one after another. In [[Poland]], [[Hungary]], and [[Bulgaria]] reforms in the government, in Poland under pressure from [[Solidarity]], prompted a peaceful end to communist rule and democratization. Elsewhere, mass-demonstrations succeeded in ousting the communists from Czechoslovakia and East Germany, where the [[Berlin Wall]] was opened and subsequently brought down in November 1989. In [[Romania]] a popular uprising deposed the [[Nicolae Ceauşescu]] regime during December and led to his execution on Christmas Day later that year. | |

| − | + | Conservatives often argue that one major cause of the demise of the Soviet Union was the massive fiscal spending on military technology that the Soviets saw as necessary in response to NATO's increased armament of the 1980s. They insist that Soviet efforts to keep up with NATO military expenditures resulted in massive economic disruption and the effective bankruptcy of the Soviet economy, which had always labored to keep up with its western counterparts. The Soviets were a decade behind the West in [[computer]]s and falling further behind every year. The critics of the USSR state that computerized military technology was advancing at such a pace that the Soviets were simply incapable of keeping up, even by sacrificing more of the already weak civilian economy. According to the critics, the arms race, both nuclear and conventional, was too much for the underdeveloped Soviet economy of the time. For this reason [[Ronald Reagan]] is seen by many conservatives as the man who 'won' the Cold War indirectly through his escalation of the arms race. However, the proximate cause for the end of the Cold War was ultimately [[Mikhail Gorbachev]]'s decision, publicized in 1988, to repudiate the [[Leonid Brezhnev]] doctrine that any threat to a socialist state was a threat to all socialist states. | |

| − | + | The Soviet Union provided little infrastructure help for its Eastern European satellites, but they did receive substantial military assistance in the form of funds, material and control. Their integration into the inefficient military-oriented economy of the Soviet Union caused severe readjustment problems after the fall of [[communism]]. | |

| − | + | Research shows that the fall of the USSR was accompanied by a sudden and dramatic decline in total warfare, interstate wars, ethnic wars, revolutionary wars, the number of refugees and displaced persons and an increase in the number of democratic states. The opposite pattern was seen before the end.<ref> Peace and Conflict 2005: A Global Survey of Armed Conflicts, Self-Determination Movements, and Democracy </ref> | |

| − | + | ==Arms race== | |

| + | ===Technology=== | ||

| + | A major feature of the Cold War was the arms race between the member states of the [[Warsaw Pact]] and those of [[NATO]]. This resulted in substantial scientific discoveries in many technological and military fields. | ||

| − | + | Some particularly revolutionary advances were made in the field of nuclear weapons and rocketry, which led to the space race (many of the rockets used to launch humans and satellites into orbit were originally based on military designs formulated during this period). | |

| − | + | Other fields in which arms races occurred include: jet fighters, bombers, [[chemical weapon]]s, [[biological weapon]]s, anti-aircraft warfare, surface-to-surface missiles (including SRBMs and cruise missiles), inter-continental ballistic missiles (as well as IRBMs), anti-ballistic missiles, anti-tank weapons, [[submarine]]s and anti-submarine warfare, submarine-launched ballistic missiles, electronic intelligence, signals intelligence, reconnaissance aircraft and spy [[satellite]]s. | |

| − | === | + | ===Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD)=== |

| − | + | One prominent feature of the nuclear arms race, especially following the massed deployment of nuclear ICBMs due to the flawed assumption that the manned bomber was fatally vulnerable to surface to air missiles, was the concept of deterrence via assured destruction, later, mutually assured destruction or "MAD." The idea was that the Western bloc would not attack the Eastern bloc or vice versa, because both sides had more than enough nuclear weapons to reduce each other out of existence and to make the entire planet uninhabitable. Therefore, launching an attack on either party would be suicidal and so neither would attempt it. With increasing numbers and accuracy of delivery systems, particularly in the closing stages of the Cold War, the possibility of a first strike doctrine weakened the deterrence theory. A first strike would aim to degrade the enemy's nuclear forces to such an extent that the retaliatory response would involve "acceptable" losses. | |

| − | == | + | ==Civil Society and the Cold War== |

| − | + | Within civil society in the West, there was great concern about the possibility of nuclear war. Civil defense plans were in place in many Western countries in case of nuclear disaster, with certain people designated for protection in secret safe-havens that were built with the expectation that occupants would survive. In late 1958 the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament was formed by such people as J. B. Priestley (1894-1984), the British writer and broadcaster, [[Bertrand Russell]] (1872-1970), the philosopher, [[A. J. P. Taylor]] (1906-90) the historian, with Peggy Duff (1910-1981) as the founder organizer. Committed to unilateral nuclear disarmament, CND held rallies, sit-ins outside nuclear basis especially when [[Margaret Thatcher]] replaced Britain's Polaris missiles with the Trident model. From 1980 to 1985 as general secretary, then from 1987 until 1990 as president, Monsignor Bruce Kent was one of the most prominent peace activists and a household name in Britain, giving Christian involvement in the disarmament campaign a very high public profile. [[Amnesty International]], founded by Catholic attorney Peter Benenson and the Quaker Eric Baker in 1961 monitored and campaigned on behalf of prisoners of conscience. The Soviet Union was especially a focus of attention. The organization is not explicitly religious and attracts both religious and non-religious activists. The organization published a great deal of material on the Soviet system and how it prevented freedom of expression and freedom of thought. In 1977 Amnesty International won the [[Nobel Prize|Nobel Peace Prize]]. Other groups were especially concerned about religious freedom behind the “Iron Curtain” (the popular term for the border between Eastern and Western Europe). Many people also focused on [[China]] during this period. | |

| + | |||

| + | ==Intelligence== | ||

| + | Military forces from the countries involved, rarely had much direct participation in the Cold War—the war was primarily fought by intelligence agencies like the [[Central Intelligence Agency]] (CIA; United States), Secret Intelligence Service (MI6; United Kingdom), Bundesnachrichtendiens (BND; West Germany), Stasi (East Germany) and the KGB (Soviet Union). | ||

| − | + | The abilities of ECHELON, a U.S.-UK intelligence sharing organization that was created during World War II, were used against the USSR, China, and their allies. | |

| − | + | According to the CIA, much of the technology in the Communist states consisted simply of copies of Western products that had been legally purchased or gained through a massive espionage program. Stricter Western control of the export of technology through COCOM (Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls) and providing defective technology to communist agents after the discovery of the Farewell Dossier contributed to the fall of communism. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Historiography== | |

| + | Three distinct periods have existed in the Western scholarship of the Cold War: the traditionalist, the revisionist, and the post-revisionist. For more than a decade after the end of World War II, few American historians saw any reason to challenge the conventional "traditionalist" interpretation of the beginning of the Cold War: that the breakdown of relations was a direct result of Stalin's violation of the accords of the Yalta conference, the imposition of Soviet-dominated governments on an unwilling Eastern Europe, Soviet intransigence and aggressive Soviet expansionism. They would point out that Marxist theory rejected liberal democracy, while prescribing a worldwide proletarian revolution and argue that this stance made conflict inevitable. Organizations such as the Comintern were regarded as actively working for the overthrow of all Western governments. | ||

| − | + | Later “New Left” revisionist historians were influenced by Marxist theory. William Appleman Williams in his 1959 ''The Tragedy of American Diplomacy'' and Walter LaFeber in his 1967 ''America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945–1966'' argued that the Cold War was an inevitable outgrowth of conflicting American and Russian economic interests. Some New Left revisionist historians have argued that U.S. policy of containment as expressed in the Truman Doctrine was at least equally responsible, if not more so, than Soviet seizure of Poland and other states. | |

| − | + | Some date the onset of the Cold War to the [[Hiroshima and Nagasaki, bombing of|Atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki]], regarding the United States’ use of nuclear weapons as a warning to the Soviet Union, which was about to join the war against the nearly defeated [[Japan]]. In short, historians have disagreed as to who was responsible for the breakdown of U.S.-Soviet relations and whether the conflict between the two superpowers was inevitable. This revisionist approach reached its height during the [[Vietnam War]] when many began to view the U.S. and the USSR as morally comparable empires. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In the later years of the Cold War, there were attempts to forge a "post-revisionist" synthesis by historians. Prominent post-revisionist historians include John Lewis Gaddis. Rather than attribute the beginning of the Cold War to the actions of either superpower, post-revisionist historians have focused on mutual misperception, mutual reactivity and shared responsibility between the leaders of the superpowers. Gaddis perceives the origins of the conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union less as the lone fault of one side or the other and more as the result of a plethora of conflicting interests and misperceptions between the two superpowers, propelled by domestic politics and bureaucratic inertia. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Melvyn Leffler contends that [[Harry S. Truman|Truman]] and [[Dwight D. Eisenhower|Eisenhower]] acted, on the whole, thoughtfully in meeting what was understandably perceived to be a potentially serious threat from a totalitarian communist regime that was ruthless at home and that might be threatening abroad. Borrowing from the realist school of international relations, the post-revisionists essentially accepted U.S. policy in Europe, such as aid to Greece in 1947 and the [[Marshall Plan]]. According to this synthesis, "communist activity" was not the root of the difficulties of Europe, but rather a consequence of the disruptive effects of the Second World War on the economic, political and social structure of Europe, which threatened to drastically alter the balance of power in a manner favorable to the USSR. | |

| − | The | + | The end of the Cold War opened many of the archives of the Communist states, providing documentation which has increased the support for the traditionalist position. Gaddis has written that [[Josef Stalin|Stalin]]'s "authoritarian, paranoid and narcissistic predisposition" locked the Cold War into place. "Stalin alone pursued personal security by depriving everyone else of it: no Western leader relied on terror to the extent that he did. He alone had transformed his country into an extension of himself: no Western leader could have succeeded at such a feat and none attempted it. He alone saw war and revolution as acceptable means with which to pursue ultimate ends: no Western leader associated violence with progress to the extent that he did."<ref>Dan Blatt, [http://www.futurecasts.com/book%20review%205-6.htm Book Review of ''We Now Know'' by John Lewis Gaddis]. Retrieved April 10, 2013.</ref> |

| − | + | ==Legacy== | |

| + | The Cold War, it has been said, was won by capitalist democracy and [[free trade]] providing goods and services better than the Soviet system. On the other hand, some of the ideals of [[Marxist]] thought, such as universal employment, welfare, and equality have tended to be neglected because they were associated with the system that failed. Marxism set out to create a [[Utopia]]n society but, without [[checks and balances]] on power, ended in a totalitarian state. | ||

| − | + | Among those who claim credit for ending the Cold War are Pope [[John Paul II]] and [[Sun Myung Moon]]. Both resolutely opposed the Soviet system, as did such Cold War warriors as [[Margaret Thatcher]] and [[Ronald Reagan]]. The [[Catholic Church]], Sun Myung Moon's Unification movement and other religious agencies, kept up a barrage of pro-democracy and pro-civil liberties propaganda that contributed to the peoples' desire, in the end, for such freedoms their leaders had denied them. Of these the most comprehensive and far ranging response to communism was that of Sun Myung Moon. His efforts included the constant mobilization and extreme levels of sacrifice by his religious followers toward this end. Further, it entailed the investment of untold resources into creating and maintaining major institutions at all levels of society devoted to opposing and challenging communism. Perhaps most importantly however was the work of his community under his direction at the philosophical and ideological level. [[Unification thought]] provided the foundation for a rigorous philosophical challenge to dialectical and historical materialism, penetratingly rendered and developed, and relentlessly disseminated by Unification philosophers. | |

| − | + | Ultimately, the Soviet system collapsed from within, unable to provide the goods and services necessary to sustain its people, or to make welfare payments to the elderly. Soviet youth felt betrayed by their revolutionary grandparents who had promised a better society than in the capitalist West. | |

| − | + | During the Cold War, both sides had unrealistic stereotypes of the other which aggravated tensions. In the [[United States]], Senator [[Joseph McCarthy]] promoted paranoia about [[communism]] through the House Committee on Un-American Activities. It targeted almost any person whose ideas and sympathies were thought to be left of center. | |

| − | + | In its foreign policy, the U.S. propped up dictators and armed insurgents, however brutal they wielded their personal power, as long as they were anti-communist. They thus aided [[Mobutu Sese Seko]] in [[Zaire]], the Contras in [[Nicaragua]] and the Taliban in [[Afghanistan]], among others. The Soviet Union did the same thing with its foreign policy, propping up dictatorial regimes that opposed the West. The [[Vietnam War]] and its conclusion reflected this policy. The Soviet Union's intervention in Afghanistan a decade later was widely referred to as the the Soviet Union's Vietnam. | |

| − | + | While both U.S. and Soviet intervention remained focused on one another, many conflicts and economic disasters went unaddressed. The [[United Nations]] Security Council suffered frequent deadlock, since the U.S. and the Soviet Union could each veto any resolution. The Soviet representative, Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov (1890-1986) was known as "Mr. Veto" because he often vetoed applications for membership of the UN. This was in part retaliation for U.S. opposition to membership of the various Soviet republics, which were considered puppet states. On September 11, 1990, U.S. president [[George H. W. Bush]] spoke of the start of a new age following the end of the Cold War, warning that dictators could no longer "count on East-West confrontation to stymie concerted United Nations action against aggression" since a "new partnership of nations" had begun. In this [[new world order]], he said, aggression would not be tolerated and all the "nations of the world, East and West, North and South, can prosper and live in harmony." He intimated that without compromising U.S. security, the defense budget could also be reduced. The end of what was often called the bi-polar age (with two world powers) has been seen as an opportunity to strengthen the United Nations. | |

| − | + | Bush set a goal of international co-operation not only to achieve peace but also to make the world a much better place—"A world where the rule of law supplants the rule of the jungle. A world in which nations recognize the shared responsibility for freedom and justice. A world where the strong respect the rights of the weak." | |

| − | The end of the Cold War | + | The end of the Cold War provided both new opportunities and dangers. Civil wars and [[terrorism]] have created a new era of international anarchy and instability in the power vacuum left by the Cold War. From the [[genocide]]s in [[Rwanda]] and [[Sudan]], to the terrorist attacks on [[September 11 attacks|September 11, 2001]], and the wars in Afghanistan and [[Iraq]] have witnessed both failure of peacekeeping by the [[United Nations]], and the inability of the [[United States]], as the lone superpower, to keep world order. A nobler and better use of power is required for future world order. |

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| − | ==Further reading== | + | ==References and Further reading== |

| − | |||

;Overviews | ;Overviews | ||

| − | * Ball, S. J. ''The Cold War: An International History, | + | * Ball, S. J. ''The Cold War: An International History, 1947–1991''. London and New York: Arnold; New York: Distributed exclusively in the United States by St. Martin’s Press, 1998. ISBN 0340591684 |

| − | * Brager, Bruce L. ''The Iron Curtain: The Cold War in Europe'' Philadelphia : Chelsea House, | + | * Brager, Bruce L. ''The Iron Curtain: The Cold War in Europe''. Philadelphia, PA: Chelsea House, 2004. ISBN 0791078329 |

| − | * Brzezinski, Zbigniew. ''The Grand Failure: The Birth and Death of Communism in the Twentieth Century'' New York : Collier Books, 1990 ISBN 0020307306 | + | * Brzezinski, Zbigniew. ''The Grand Failure: The Birth and Death of Communism in the Twentieth Century''. New York: Collier Books, 1990. ISBN 0020307306 |

| − | + | * Flory, Harriette and Jenike, Samual. ''The Modern World 16th Century to Present''. White Plains, NY: Longman, 1988. ISBN 0582367565 | |

| − | * Flory, Harriette and Jenike, Samual. ''The Modern World 16th | + | * Friedman, Norman. ''The Fifty Year War: Conflict and Strategy in the Cold War''. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2000. ISBN 1557502641 |

| − | * Friedman, Norman. ''The Fifty Year War: Conflict and Strategy in the Cold War'' Annapolis, | + | * Gaddis, John Lewis. ''The Cold War: A New History''. New York: Penguin Press, 2005. ISBN 1594200629 |

| − | * Gaddis, John Lewis. ''The Cold War: A | + | * Gaddis, John Lewis. ''Russia, the Soviet Union and the United States. An Interpretative History'' 2nd Ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1990. ISBN 0075572583 |

| − | * Gaddis, John Lewis. ''Russia, the Soviet Union and the United States. An Interpretative History'' 2nd | + | * Gaddis, John Lewis. ''Long Peace: Inquiries into the History of the Cold War''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 0195043367 |

| − | * Gaddis, John Lewis. ''Long Peace: Inquiries into the History of the Cold War'' New York : Oxford University Press, 1987 ISBN 0195043367 | + | * Gaddis, John Lewis. ''Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of Postwar American National Security Policy''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982. ISBN 0195030974 |

| − | * Gaddis, John Lewis. ''Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of Postwar American National Security Policy'' New York : Oxford University Press, 1982 ISBN 0195030974 | + | * LaFeber, Walter. ''America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945–1992'' 8th Ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1997. ISBN 0070360642 |

| − | * LaFeber, Walter. ''America, Russia, and the Cold War, | + | * Lundestad, Geir. ''East, West, North, South: Major Developments in International Relations since 1945'', translated from the Norwegian by Gail Adams Kvam, 5th ed. London & Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2005. ISBN 1412907489 |

| − | * Lundestad, Geir. ''East, West, North, South : Major Developments in International Relations since 1945'', translated from the Norwegian by Gail Adams Kvam, 5th ed | + | * Ninkovich, Frank. ''Germany and the United States: The Transformation of the German Question since 1945''. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1995. ISBN 0805792236 |

| − | * Ninkovich, Frank. ''Germany and the United States: The Transformation of the German Question since 1945'' New York : Twayne Publishers | + | * Paterson, Thomas G. ''Meeting the Communist Threat: Truman to Reagan''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0195045335 |

| − | * Paterson, Thomas G. ''Meeting the Communist Threat: Truman to Reagan'' New York : Oxford University Press, 1988 ISBN 0195045335 | + | * Powaski, Ronald E. ''The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917–1991''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0195078519 |

| − | * Powaski, Ronald E. ''The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, | + | * Sivachev, Nikolai and Nikolai Yakolev. ''Russia and the United States''. Chicago, I.L: University of Chicago Press, 1979. ISBN 0226761495 |

| − | * Sivachev, Nikolai and Yakolev | + | * Ulam, Adam B. ''Expansion and Coexistence: Soviet Foreign Policy, 1917–1973'', 2nd Ed. New York: Praeger, 1974. |

| − | * Ulam, Adam B. ''Expansion and Coexistence: Soviet Foreign Policy, | + | * Westad, Odd Arne. ''The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of our Times''. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0521853648 |

| − | * Westad, Odd Arne ''The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of our Times'' Cambridge | ||

| − | |||

;Historiography | ;Historiography | ||

| − | + | * Fitzpatrick, Sheila. "Russia's Twentieth Century in History and Historiography." ''The Australian Journal of Politics and History'' 46 (2000). | |

| + | * Gaddis, John Lewis. ''We Now Know: Rethinking Cold War History''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 0198780702 | ||

| + | * Kort, Michael. ''The Columbia Guide to the Cold War''. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998. ISBN 0231107722 | ||

| + | * Matlock, Jack E. "The End of the Cold War." ''Harvard International Review'' 23 (2001). | ||

| + | * Walker, J. Samuel. "Historians and Cold War Origins: The New Consensus" in Gerald K. Haines and J. Samuel Walker (eds.). ''American Foreign Relations: A Historiographical Review'' (1981): 207–236. | ||

| + | * White, Timothy J. "Cold War Historiography: New Evidence Behind Traditional Typographies." ''International Social Science Review'' (2000). | ||

| + | * Williams, William Appleman. ''The Tragedy of American Diplomacy''. W. W. Norton & Company, 1988. ISBN 0393304930 | ||

| + | ** Berger, Henry W. (ed.). ''A William Appleman Williams Reader'' Chicago: I.R. Dee, 1992. ISBN 1566630029 | ||

| + | ** Gardner, Lloyd C. (ed.). ''Redefining the Past: Essays in Diplomatic History in Honor of William Appleman Williams''. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 1986. ISBN 0870713485 | ||

| + | * Westad, Odd Arne (ed.). ''Reviewing the Cold War: Approaches, Interpretations, Theory'' Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0521853648 | ||

| − | * | + | ;Origins: to 1950 |

| − | * | + | * Chen Jian, ''China's Road to the Korean War: Making of the Sino-American Confrontation''. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994. ISBN 0231100248 |

| − | * | + | * Cumings, Bruce. ''The Origins of the Korean War''. Two volumes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981-1990. ISBN 0691101132 (v. 1); ISBN 0691078432 (v. 2). |

| − | * | + | * Gaddis, John Lewis. ''The United States and the Origins of the Cold War, 1941–1947''. New York: Columbia University Press, 2000. ISBN 023112239X |

| − | * | + | * Holloway, David. ''Stalin and the Bomb: The Soviet Union and Atomic Energy, 1959–1956'' New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994. ISBN 0300060564 |

| − | * | + | * Goncharov, Sergei, John Wilson Lewis and Litai Xue. ''Uncertain Partners: Stalin, Mao and the Korean War''. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1993. ISBN 0804721157 |

| − | + | * Leffler, Melvyn. ''A Preponderance of Power: National Security, the Truman Administration and the Cold War''. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1992. ISBN 0804719241 | |

| − | * | + | * Mastny, Vojtech. ''Russia's Road to the Cold War: Diplomacy, Warfare, and the Politics of Communism, 1941–1945''. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979. ISBN 0231043600 |

| − | * | + | * Levering, Ralph, Vladamir Pechatnov, Verena Botzenhart-Viehe, and C. Earl Edmondson. ''Debating the Origins of the Cold War''. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002. ISBN 0847694089 |

| − | * | + | * Trachtenberg, Marc. ''A Constructed Peace: The Making of the European Settlement, 1945–1963''. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999. ISBN 0691002738 |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

;Intelligence | ;Intelligence | ||

| − | + | * Aldrich, Richard J. ''The Hidden Hand: Britain, America and Cold War Secret Intelligence''. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2002. ISBN 1585672742 | |

| − | * Aldrich, Richard J. ''The Hidden Hand: Britain, America and Cold War Secret Intelligence'' Woodstock, NY : Overlook Press, 2002 ISBN 1585672742 | + | * Ambrose, Stephen E. ''Ike's Spies: Eisenhower and the Intelligence Establishment''. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi Banner Books, 1999. ISBN 1578062071 |

| − | * Ambrose, Stephen E. ''Ike's Spies: Eisenhower and the Intelligence Establishment'' Jackson : University Press of Mississippi Banner Books, | + | * Andrew, Christopher and Vasili Mitrokhin. ''The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB''. New York: Basic Books, 1999. ISBN 0465003109 |

| − | * Andrew, Christopher and Mitrokhin | + | * Andrew, Christopher, and Oleg Gordievsky. ''KGB: The Inside Story of Its Foreign Operations from Lenin to Gorbachev''. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1990. ISBN 0060166053 |

| − | + | * Bogle, Lori (ed.). ''Cold War Espionage and Spying''. London: Routledge, 2001. ISBN 0815332416 | |

| − | * Andrew, Christopher, and Gordievsky | + | * Dorril, Stephen. ''MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty's Secret Intelligence Service''. New York: Free Press, 2000. ISBN 0743203798 |

| − | * Bogle, Lori | + | * Gates, Robert M. ''From the Shadows: The Ultimate Insider's Story of Five Presidents and How They Won the Cold War''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996. ISBN 0684810816 |

| − | * Dorril, Stephen. ''MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty's Secret Intelligence Service'' New York : Free Press, | + | * Haynes, John Earl, and Harvey Klehr. ''Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America''. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999. ISBN 0300077718 |

| − | * Gates, Robert M. ''From | + | * Helms, Richard. ''A Look over My Shoulder: A Life in the Central Intelligence Agency''. New York: Random House, 2003. ISBN 037550012X |

| − | * Haynes, John Earl, and Klehr | + | * Koehler, John O. ''Stasi: The Untold Story of the East German Secret Police''. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1999. ISBN 0813334098 |

| − | * Helms, Richard. ''A Look over My Shoulder: A Life in the Central Intelligence Agency'' New York : Random House, | + | * Murphy, David E., Sergei A.Kondrashev, and George Bailey. ''Battleground Berlin: CIA vs. KGB in the Cold War''. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997. ISBN 0300072333 |

| − | * Koehler, John O. ''Stasi: The Untold Story of the East German Secret Police'' Boulder, | + | * Prados, John. ''Presidents' Secret Wars: CIA and Pentagon Covert Operations Since World War II''. New York: William Morrow, 1986. ISBN 068805384X |

| − | * Murphy, David E. | + | * Rositzke, Harry. 1977. ''The CIA's Secret Operations: Espionage, Counterespionage, and Covert Action''. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1988. ISBN 0813376041 |

| − | * Prados, John. ''Presidents' Secret Wars: CIA and Pentagon Covert Operations Since World War II'' New York : | + | * Trahair, Richard C. S. ''Encyclopedia of Cold War Espionage, Spies and Secret Operations''. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004. ISBN 0313319553 |

| − | * Rositzke, Harry. ''The CIA's Secret Operations: Espionage, Counterespionage, and Covert Action'' Boulder : Westview Press, 1988 | + | * Weinstein, Allen, and Alexander Vassiliev. ''The Haunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America—The Stalin Era''. New York: Random House, 1999. ISBN 0679457240 |

| − | * Trahair, Richard C. S. ''Encyclopedia of Cold War Espionage, Spies and Secret Operations'' Westport, | ||

| − | * Weinstein, Allen, and Vassiliev | ||

| − | |||

;1950s and 1960s | ;1950s and 1960s | ||

| − | + | * Beschloss, Michael. ''Kennedy v. Khrushchev: The Crisis Years, 1960–63''. New York: Edward Burlingame Books, 1991. ISBN 0060164549 | |

| − | * Beschloss, Michael. ''Kennedy v. Khrushchev: The Crisis Years, | + | * Brands, H. W. ''Cold Warriors. Eisenhower's Generation and American Foreign Policy''. New York: Columbia University Press, 1988. ISBN 0231065264 |

| − | * Brands, H. W. ''Cold Warriors. Eisenhower's Generation and American Foreign Policy'' New York : Columbia University Press, 1988 ISBN 0231065264 | + | * Brands, H. W. ''The Wages of Globalism: Lyndon Johnson and the Limits of American Power''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0195078888 |

| − | * Brands, H. W. ''The Wages of Globalism: Lyndon Johnson and the Limits of American Power '' New York : Oxford University Press, 1995 ISBN 0195078888 | + | * Brzezinski, Zbigniew. ''Soviet Bloc: Unity and Conflict''. New York: Praeger, 1961. ISBN 0674825454 |

| − | * Brzezinski, Zbigniew. ''Soviet Bloc: Unity and Conflict'' | + | * Chen Jian. ''Mao's China and the Cold War''. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001. ISBN 0807849324 |

| − | * Chen Jian | + | * Divine, Robert A. ''Eisenhower and the Cold War''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1981. ISBN 0195028244 |

| − | * Divine, Robert A. ''Eisenhower and the Cold War'' New York : Oxford University Press, 1981 ISBN 0195028244 | + | * Divine, Robert A. (ed.). ''The Cuban Missile Crisis'' 2nd ed. New York: M. Wiener Pub., 1988. ISBN 091012986X |

| − | * Divine, Robert A. ed. | + | * Freedman, Lawrence. ''Kennedy's Wars: Berlin, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0195134532 |

| − | * Freedman, Lawrence. ''Kennedy's Wars: Berlin, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam'' New York : Oxford University Press, 2000 ISBN 0195134532 | + | * Fursenko, Aleksandr and Timothy J. Naftali. ''One Hell of a Gamble: Khrushchev, Castro, and Kennedy, 1958–1964''. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1997. ISBN 0393040704 |

| − | * Fursenko, Aleksandr and | + | * Kunz, Diane B. ''The Diplomacy of the Crucial Decade: American foreign Relations during the 1960s''. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994. ISBN 0231081774 |

| − | * Kunz, Diane B. ''The Diplomacy of the Crucial Decade: American foreign Relations during the 1960s'' New York : Columbia University Press, | + | * Navratil, Jaromir. ''The Prague Spring ‘68''. New York: Central European University Press, 1998. ISBN 9639116157 |

| − | * Navratil, Jaromir. ''The Prague Spring | + | * Mastny, Vojtech. ''The Cold War and Soviet Insecurity: The Stalin Years''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 0195106164 |

| − | * Mastny, Vojtech. ''The Cold War and Soviet Insecurity: The Stalin Years'' New York : Oxford University Press, 1996 ISBN 0195106164 | + | * Melanson, Richard A. and David Allan Mayers (eds.). ''Reevaluating Eisenhower. American Foreign Policy in the 1950s''. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1987. ISBN 0252013409 |

| − | * Melanson, | + | * Paterson, Thomas G. (ed.). ''Kennedy's Quest for Victory: American Foreign Policy, 1961–1963''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989. ISBN 019504584X |

| − | * Paterson, Thomas G. ed. | + | * Reynolds, David (ed.). ''The Origins of the Cold War in Europe: International Perspectives''. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994. ISBN 0300058926 |

| − | * Reynolds, David | + | * Stueck Jr., William W. ''The Korean War: An International History''. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995. ISBN 0691037671 |

| − | * Stueck | + | * Vandiver, Frank E. ''Shadows of Vietnam: Lyndon Johnson's Wars''. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 1997. ISBN 0890967474 |

| − | * Vandiver, Frank E. ''Shadows of Vietnam: Lyndon Johnson's Wars'' College Station : Texas A&M University Press, | + | * Williams, Kirrian. ''The Prague Spring and its Aftermath: Czechoslovak Politics, 1968–1970''. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 0521588030 |

| − | * Williams, Kirrian. ''The Prague Spring and its Aftermath : Czechoslovak Politics, | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | ;Détente: 1969–1979 | |

| − | ; | + | * Edmonds, Robin. ''Soviet Foreign Policy: The Brezhnev Years''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983. ISBN 019285125X |

| − | + | * Garthoff, Raymond. ''Détente and Confrontation: American-Soviet Relations from Nixon to Reagan'', 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1994. ISBN 0815730411. | |

| − | * Edmonds, Robin. ''Soviet Foreign Policy: The Brezhnev Years'' | + | * Isaacson, Walter. ''Kissinger''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992. ISBN 0671663232 |

| − | * Garthoff, Raymond. ''Détente and Confrontation: American-Soviet Relations from Nixon to Reagan'', 2nd ed. | + | * Kissinger, Henry. ''White House Years''. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co. ISBN 0316496618 |

| − | * Isaacson, Walter. ''Kissinger'' New York : Simon & Schuster, | + | * Kissinger, Henry. ''Years of Upheaval''. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1982. ISBN 0316285919 |

| − | * Kissinger, Henry. ''White House Years'' Boston : Little, Brown | + | * Ulam, Adam B. ''Dangerous Relations. The Soviet Union in World Politics, 1970–1982''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983. ISBN 0195032373 |

| − | |||

| − | * Ulam, Adam B. ''Dangerous Relations. The Soviet Union in World Politics, | ||

| − | |||

| − | ;Second Cold War: | + | ;Second Cold War: 1979–1986 |

| − | + | * Brzezinski, Zbigniew. ''Power and Principle: Memoirs of the National Security Adviser, 1977–1981''. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1985. ISBN 0374518777 | |

| − | * Brzezinski, Zbigniew. ''Power and Principle: Memoirs of the National Security Adviser, | + | * Edmonds, Robin. ''Soviet Foreign Policy: The Brezhnev Years''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983. ISBN 019285125X |

| − | * Edmonds, Robin. ''Soviet Foreign Policy: The Brezhnev Years'' | + | * Mower, A. Glenn Jr. ''Human Rights and American Foreign Policy: The Carter and Reagan Experiences''. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1987. ISBN 0313250820 |

| − | * Mower, A. Glenn Jr. ''Human Rights and American Foreign Policy: The Carter and Reagan Experiences'' | + | * Smith, Gaddis. ''Morality, Reason and Power: American Diplomacy in the Carter Years''. New York: Hill and Wang, 1986. ISBN 0809070170 |

| − | * Smith, Gaddis. ''Morality, Reason and Power:American Diplomacy in the Carter Years'' New York : Hill and Wang, 1986 ISBN 0809070170 | ||

| − | |||

| − | ;End of Cold War: | + | ;End of Cold War: 1986–1991 |

| − | + | * Beschloss, Michael, and Strobe Talbott. ''At the Highest Levels: The Inside Story of the End of the Cold War''. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co., 1993. ISBN 0316092819 | |

| − | * Beschloss, Michael, and Talbott | + | * Bialer, Seweryn and Michael Mandelbaum (eds.). ''Gorbachev's Russia and American Foreign Policy''. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1988. ISBN 0813307511 |

| − | * Bialer, Seweryn and Mandelbaum | + | * Gaddis, John Lewis. ''The United States and the End of the Cold War: Implications, Reconsiderations, Provocations''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 0195052013 |

| − | * Gaddis, John Lewis. ''The United States and the End of the Cold War: Implications, Reconsiderations, Provocations'' New York : Oxford University Press, 1992 ISBN 0195052013 | + | * Garthoff, Raymond. ''The Great Transition: American-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War''. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1994. ISBN 0815730594 |

| − | * Garthoff, Raymond. ''The Great Transition:American-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War'' Washington, | + | * Hogan, Michael (ed.). ''The End of the Cold War: Its Meaning and Implications''. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 0521437318 |

| − | * Hogan, Michael ed. ''The End of the Cold War | + | * Kyvig, David ed. ''Reagan and the World'' New York : Greenwood Press, 1990 ISBN 0313273413 |

| − | * Kyvig, David ed. ''Reagan and the World'' New York : Greenwood Press, 1990 ISBN 0313273413 | + | * Matlock, Jack F. ''Autopsy of an Empire: the American Ambassador’s Account of the Collapse of the Soviet Union''. New York: Random House, 1995. ISBN 0679413766 |

| − | * Matlock, Jack F. ''Autopsy of an Empire : the American | + | * Ward, Thomas, ''March to Moscow—The Role of the Reverend Sun Myung Moon in the Collapse of Communism''. St. Paul, MN: RIIWT/Paragon House 2006) ISBN 1885118163 |

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

;Economics and Internal Forces | ;Economics and Internal Forces | ||

| − | + | * Heiss, Mary Ann. "The Economic Cold War: America, Britain, and East-West Trade, 1948–63." ''The Historian'' 65 (2003). | |

| − | * Heiss, Mary Ann. "The Economic Cold War: America, Britain, and East-West Trade, | + | * Hogan, Michael J. ''The Marshall Plan: America, Britain and the Reconstruction of Western Europe, 1947–1952''. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987. ISBN 0521251400 |

| − | * Hogan, Michael J. ''The Marshall Plan: America, Britain and the Reconstruction of Western Europe, | + | * Keohane, Robert O. and Joseph S. Nye. ''Power and Interdependence'' 3rd Edition. Longman, 2000. ISBN 0321048571 |

| − | * Keohane, Robert O. and Joseph S. Nye. ''Power and Interdependence'' 3rd Edition Longman | + | * Kunz, Diane B. ''Butter and Guns: America's Cold War Economic Diplomacy''. New York: Free Press, 1997. ISBN 0684827956 |

| − | * Kunz, Diane B. ''Butter and Guns: America's Cold War Economic Diplomacy'' New York : Free Press, | + | * Morgan, Patrick M., Keith L. Nelson and G. A. Arbatov (eds.). ''Re-Viewing the Cold War: Domestic Factors and Foreign Policy in the East-West Confrontation''. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2000. ISBN 0275966372 |

| − | * Morgan, Patrick M. | ||

| − | |||

;Popular culture | ;Popular culture | ||

| − | + | * Boyer, Paul S. ''By the Bomb's Early Light: American Thought and Culture at the Dawn of the Atomic Age''. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1994. ISBN 0807844802 | |

| − | * Boyer, Paul S. ''By the Bomb's Early Light: American Thought and Culture at the Dawn of the Atomic Age'' Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, 1994 ISBN 0807844802 | + | * Hendershot, Cynthia. ''I Was a Cold War Monster: Horror Films, Eroticism and the Cold War Imagination''. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 2001. ISBN 0879728507 |

| − | * Hendershot, Cynthia. | + | * Mulvihill, Jason. "James Bond's Cold War Part I." ''Journal of Instructional Media'' 28 (2001). |

| − | * Mulvihill, Jason. "James Bond's Cold War Part I" ''Journal of Instructional Media'' | + | * Schwartz, Richard Alan. ''Cold War Culture: Media and the Arts, 1945–1990''. New York: Checkmark Books, 2000. ISBN 0816042640 |

| − | * Schwartz, Richard Alan. | + | * Shapiro Jerome F. ''Atomic Bomb Cinema: The Apocalyptic Imagination on Film''. New York: Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0415936608 |

| − | * Shapiro Jerome F. ''Atomic Bomb Cinema: The Apocalyptic Imagination on Film'' New York : Routledge, 2002 ISBN 0415936608 | + | * Whitfield, Stephen J. ''The Culture of the Cold War''. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996. ISBN 0801851955 |

| − | * Whitfield, Stephen J. ''The Culture of the Cold War'' Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press, | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

;Primary sources: Documents and memoirs | ;Primary sources: Documents and memoirs | ||

| − | + | * Acheson, Dean. ''Present at the Creation: My Years in the State Department''. London, Hamilton, 1970. ISBN 0241018668 | |

| − | * Acheson, Dean. ''Present at the Creation: My Years in the State Department'' London, Hamilton, 1970 ISBN 0241018668 | + | * Etzold, Thomas and John Lewis Gaddis (eds.). ''Containment: Documents on American Policy and Strategy, 1945–1950''. New York: Columbia University Press, 1978. ISBN 0231043988 |

| − | |||

| − | * Etzold, Thomas and | ||

| − | |||

* Khrushchev, Nikita Sergeevich. Memoirs: | * Khrushchev, Nikita Sergeevich. Memoirs: | ||

| − | ** Talbott, Strobe | + | ** Talbott, Strobe (ed.). ''Khrushchev Remembers''. London: Deutsch, 1971. ISBN 0233963383 |

| − | + | *** Schecter, Jerrold L. and Vyacheslav V. Luchkov (eds.). ''Khrushchev Remembers: The Glasnost Tapes''. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co., 1990. ISBN 0316472972 | |

| − | *** Schecter, Jerrold L. and | ||

* Kissinger, Henry | * Kissinger, Henry | ||

| − | ** | + | ** Vol. 1 ''White House Years''. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co., 1979. ISBN 0316496618 |

| − | ** | + | ** Vol. 2 ''Years of Upheaval''. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co., 1982. ISBN 0316285919 |

| − | ** | + | ** Vol. 3 ''Years of Renewal''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999. ISBN 0684855712 |

| − | * Nixon, Richard. ''RN : | + | * Nixon, Richard. ''RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990. ISBN 0671707418 |

| − | * Shultz, George P. ''Turmoil and Triumph: My Years as Secretary of State'' New York : | + | * Shultz, George P. ''Turmoil and Triumph: My Years as Secretary of State''. New York: Scribner, 1993. ISBN 0684193256 |

| − | * Hanhimäki, Jussi M. and | + | * Hanhimäki, Jussi M. and Odd Arne Westad (eds.). ''The Cold War: A History in Documents and Eyewitness Accounts''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0198208626 |

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved January 7, 2024. | |

*[http://www.cwihp.org The Cold War International History Project (CWIHP)] | *[http://www.cwihp.org The Cold War International History Project (CWIHP)] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*[http://www.western-allies-berlin.com History of the Western allies in Berlin during the Cold War] | *[http://www.western-allies-berlin.com History of the Western allies in Berlin during the Cold War] | ||

| − | |||

*[http://www.coldwar.org The Cold War Museum] | *[http://www.coldwar.org The Cold War Museum] | ||

| − | + | *[http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/themes/world_politics/cold_war/default.stm Video and audio news reports from during the Cold War] | |

| − | *[http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/themes/world_politics/cold_war/default.stm Video and audio news reports from during the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | + | {{credit|63093196}} |

| − | + | [[Category:Public]] | |

| − | |||

| − | [[Category: | ||

[[Category:History]] | [[Category:History]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 22:28, 7 January 2024

The Cold War was the protracted ideological, geopolitical, and economic struggle that emerged after World War II between the global superpowers of the Soviet Union and the United States, supported by their military alliance partners. It lasted from the end of World War II until the period preceding the demise of the Soviet Union on December 25, 1991.

The global confrontation between the West and communism was popularly termed The Cold War because direct hostilities never occurred between the United States and the Soviet Union. Instead, the "war" took the form of an arms race involving nuclear and conventional weapons, military alliances, economic warfare and targeted trade embargos, propaganda, and disinformation, espionage and counterespionage, proxy wars in the developing world that garnered superpower support for opposing sides within civil wars. The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 was the most important direct confrontation, together with a series of confrontations over the Berlin Blockade and the Berlin Wall. The major civil wars polarized along Cold War lines were the Greek Civil War, Korean War, Vietnam War, the war in Afghanistan, as well as the conflicts in Angola, El Salvador, and Nicaragua.

During the Cold War there was concern that it would escalate into a full nuclear exchange with hundreds of millions killed. Both sides developed a deterrence policy that prevented problems from escalating beyond limited localities. Nuclear weapons were never used in the Cold War.

The Cold War cycled through a series of high and low tension years (the latter called detente). It ended in the period between 1988 and 1991 with the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, the emergence of Solidarity, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and the demise of the Soviet Union itself.

Historians continue to debate the reasons for the Soviet collapse in the 1980s. Some fear that as one super-power emerges without the limitations imposed by a rival, the world may become a less secure place. Many people, however, see the end of the Cold War as representing the triumph of democracy and freedom over totalitarian rule, state-mandated atheism, and a repressive communist system that claimed the lives of millions. While equal blame for Cold War tensions is often attributed both to the United States and the Soviet Union, it is evident that the Soviet Union had an ideological focus that found the Western democratic and free market systems inherently oppressive and espoused their overthrow, beginning with the Communist Manifesto of 1848.

Origin of the Term "Cold War"

The origins of the term "Cold War" are debated. The term was used hypothetically by George Orwell in 1945, though not in reference to the struggle between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, which had not yet been initiated. American politician Bernard Baruch began using the term in April 1947 but it first came into general use in September 1947 when journalist Walter Lippmann published a book on U.S.-Soviet tensions entitled The Cold War.

Historical overview

Origins

Tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States resumed following the conclusion of the Second World War in August 1945. As the war came to a close, the Soviets laid claim to much of Eastern Europe and the Northern half of Korea. They also attempted to occupy Japanese northernmost island of Hokkaido and lent logistic and military support to Mao Zedong in his efforts to overthrow the Chinese Nationalist forces. Tensions between the Soviet Union and the Western powers escalated between 1945–1947, especially when in Potsdam, Yalta, and Tehran, Stalin's plans to consolidate Soviet control of Central and Eastern Europe became manifestly clear. On March 5, 1946 Winston Churchill delivered his landmark speech at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri lamenting that an "iron curtain" had descended on Eastern Europe.

Historians interpret the Soviet Union's Cold War intentions in two different manners. One emphasizes the primacy of communist ideology and communism's foundational intent, as outlined in the Communist Manifesto, to establish global hegemony. The other interpretation, advocated notably by Richard M. Nixon, emphasized the historical goals of the Russian state, specifically hegemony over Eastern Europe, access to warm water seaports, the defense of other Slavic peoples, and the view of Russia as "the Third Rome." The roots of the ideological clashes can be seen in Marx's and Engels' writings and in the writings of Vladimir Lenin who succeeded in building communism into a political reality through the Bolshevik seizure of power in the Russian Revolution of 1917. Walter LaFeber stresses Russia's historic interests, going back to the Czarist years when the United States and Russia became rivals. From 1933 to 1939 the United States and the Soviet Union experienced détente but relations were not friendly. After the USSR and Germany became enemies in 1941, Franklin Delano Roosevelt made a personal commitment to help the Soviets, although the U. S. Congress never voted to approve any sort of alliance and the wartime cooperation was never especially friendly. For example, Josef Stalin was reluctant to allow American forces to use Soviet bases. Cooperation became increasingly strained by February 1945 at the Yalta Conference, as it was becoming clear that Stalin intended to spread communism to Eastern Europe—and then, perhaps—to France and Italy.

Some historians such as William Appleman Williams also cite American economic expansionism as one of the roots of the Cold War. These historians use the Marshall Plan and its terms and conditions as evidence to back up their claims.

These geopolitical and ideological rivalries were accompanied by a third factor that had just emerged from World War II as a new problem in world affairs: the problem of effective international control of nuclear energy. In 1946 the Soviet Union rejected a United States proposal for such control, which had been formulated by Bernard Baruch on the basis of an earlier report authored by Dean Acheson and David Lilienthal, with the objection that such an agreement would undermine the principle of national sovereignty. The end of the Cold War did not resolve the problem of international control of nuclear energy, and it has re-emerged as a factor in the beginning of the Long War (or the war on global terror) declared by the United States in 2006 as its official military doctrine.

Global Realignments

This period began the Cold War in 1947 and continued until the change in leadership for both superpowers in 1953—from Presidents Harry S. Truman to Dwight D. Eisenhower in the United States, and from Josef Stalin to Nikita Khrushchev in the Soviet Union.

Notable events include the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan, the Berlin Blockade and Berlin Airlift, the Soviet Union's detonation of its first atomic bomb, the formation of NATO in 1949 and the Warsaw Pact in 1955, the formation of East and West Germany, the Stalin Note for German reunification of 1952 superpower disengagement from Central Europe, the Chinese Civil War and the Korean War.

The American Marshall Plan intended to rebuild the European economy after the devastation incurred by the Second World War in order to thwart the political appeal of the radical left. For Western Europe, economic aid ended the dollar shortage, stimulated private investment for postwar reconstruction and, most importantly, introduced new managerial techniques. For the U.S., the plan rejected the isolationism of the 1920s and integrated the North American and Western European economies. The Truman Doctrine refers to the decision to support Greece and Turkey in the event of Soviet incursion, following notice from Britain that she was no longer able to aid Greece in its civil war against communist activists. The Berlin blockade took place between June 1948 and July 1949, when the Soviets, in an effort to obtain more post-World War II concessions, prevented overland access to the allied zones in Berlin. Thus, personnel and supplies were lifted in by air. The Stalin Note was a plan for the reunification of Germany on the condition that it became a neutral state and that all Western troops be withdrawn.

Escalation and Crisis

A period of escalation and crisis existed between the change in leadership for both superpowers from 1953—with Josef Stalin’s sudden death and the American presidential election of 1952—until the resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962.

Events included the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, the erection of the Berlin Wall in 1961, the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 and the Prague Spring in 1968. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, in particular, the world was closest to a third (nuclear) world war. The Prague Spring was a brief period of hope, when the government of Alexander Dubček (1921–1992) started a process of liberalization, which ended abruptly when the Russian Soviets invaded Czechoslovakia.

Thaw and Détente, 1962-1979

The Détente period of the Cold War was marked by mediation and comparative peace. At its most reconciliatory, German Chancellor Willy Brandt forwarded the foreign policy of Ostpolitik during his tenure in the Federal Republic of Germany. Translated literally as "eastern politics," Egon Bahr, its architect and advisor to Brandt, framed this policy as "change through rapprochement."

These initiatives led to the Warsaw Treaty between Poland and West Germany on December 7, 1970; the Quadripartite or Four-Powers Agreement between the Soviet Union, United States, France and Great Britain on September 3, 1971; and a few east-west German agreements including the Basic Treaty of December 21, 1972.

Limitations to reconciliation did exist, evidenced by the deposition of Walter Ulbricht by Erich Honecker as East German General Secretary on May 3, 1971.

Second Cold War

The period between the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and the rise of Mikhail Gorbachev as Soviet leader in 1985 was characterized by a marked "freeze" in relations between the superpowers after the "thaw" of the Détente period of the 1970s. As a result of this reintensification, the period is sometimes referred to as the "Second Cold War."

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 in support of an embryonic communist regime in that country led to international outcries and the widespread boycotting of the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games by many Western countries in protest at Soviet actions. The Soviet invasion led to a protracted conflict, which involved Pakistan—an erstwhile U.S. ally—in locked horns with the Soviet military might for over 12 years.

Worried by Soviet deployment of nuclear SS-20 missiles (commenced in 1977), NATO allies agreed in 1979 to continued Strategic Arms Limitation Talks to constrain the number of nuclear missiles for battlefield targets, while threatening to deploy some five hundred cruise missiles and MGM-31 Pershing II missiles in West Germany and the Netherlands if negotiations were unsuccessful. The negotiations failed, as expected. The planned deployment of the Pershing II met intense and widespread opposition from public opinion across Europe, which became the site of the largest demonstrations ever seen in several countries. Pershing II missiles were deployed in Europe beginning in January 1984, and were withdrawn beginning in October 1988.

The "new conservatives" or "neoconservatives" rebelled against both the Richard Nixon-era policies and the similar position of Jimmy Carter toward the Soviet Union. Many clustered around hawkish Senator Henry "Scoop" Jackson, a Democrat, and pressured President Carter into a more confrontational stance. Eventually they aligned themselves with Ronald Reagan and the conservative wing of the Republicans, who promised to end Soviet expansionism.

The elections, first of Margaret Thatcher as British prime minister in 1979, followed by that of Ronald Reagan to the American presidency in 1980, saw the elevation of two hard-line warriors to the leadership of the Western Bloc.

Other events included the Strategic Defense Initiative and the Solidarity Movement in Poland.

"End" of the Cold War

This period began at the rise of Mikhail Gorbachev as Soviet leader in 1985 and continued until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Events included the Chernobyl accident in 1986, and the Autumn of Nations—when one by one, communist regimes collapsed. This includes the famous fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989), the Soviet coup attempt of 1991 and collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Other noteworthy events include the implementation of the policies of glasnost and perestroika, public discontent over the Soviet Union's war in Afghanistan, and the socio-political effects of the Chernobyl nuclear plant accident in 1986. East-West tensions eased rapidly after the rise of Mikhail Gorbachev. After the deaths of three elderly Soviet leaders in quick succession beginning with Leonoid Breshnev in 1982, the Politburo elected Gorbachev Soviet Communist Party chief in 1985, marking the rise of a new generation of leadership. Under Gorbachev, relatively young reform-oriented technocrats rapidly consolidated power, providing new momentum for political and economic liberalization and the impetus for cultivating warmer relations and trade with the West.

Meanwhile, in his second term, Ronald Reagan surprised the neoconservatives by meeting with Gorbachev in Geneva, Switzerland in 1985 and Reykjavík, Iceland in 1986. The latter meeting focused on continued discussions around scaling back the intermediate missile arsenals in Europe. The talks were unsuccessful. Afterwards, Soviet policymakers increasingly accepted Reagan's administration warnings that the U.S. would make the arms race an increasing financial burden for the USSR. The twin burdens of the Cold War arms race on one hand and the provision of large sums of foreign and military aid, upon which the socialist allies had grown to expect, left Gorbachev's efforts to boost production of consumer goods and reform the stagnating economy in an extremely precarious state. The result was a dual approach of cooperation with the west and economic restructuring (perestroika) and democratization (glasnost) domestically, which eventually made it impossible for Gorbachev to reassert central control over Warsaw Pact member states.

Thus, beginning in 1989 Eastern Europe's communist governments toppled one after another. In Poland, Hungary, and Bulgaria reforms in the government, in Poland under pressure from Solidarity, prompted a peaceful end to communist rule and democratization. Elsewhere, mass-demonstrations succeeded in ousting the communists from Czechoslovakia and East Germany, where the Berlin Wall was opened and subsequently brought down in November 1989. In Romania a popular uprising deposed the Nicolae Ceauşescu regime during December and led to his execution on Christmas Day later that year.

Conservatives often argue that one major cause of the demise of the Soviet Union was the massive fiscal spending on military technology that the Soviets saw as necessary in response to NATO's increased armament of the 1980s. They insist that Soviet efforts to keep up with NATO military expenditures resulted in massive economic disruption and the effective bankruptcy of the Soviet economy, which had always labored to keep up with its western counterparts. The Soviets were a decade behind the West in computers and falling further behind every year. The critics of the USSR state that computerized military technology was advancing at such a pace that the Soviets were simply incapable of keeping up, even by sacrificing more of the already weak civilian economy. According to the critics, the arms race, both nuclear and conventional, was too much for the underdeveloped Soviet economy of the time. For this reason Ronald Reagan is seen by many conservatives as the man who 'won' the Cold War indirectly through his escalation of the arms race. However, the proximate cause for the end of the Cold War was ultimately Mikhail Gorbachev's decision, publicized in 1988, to repudiate the Leonid Brezhnev doctrine that any threat to a socialist state was a threat to all socialist states.