Berber

| Berbers |

|---|

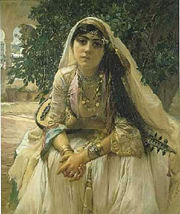

| 200px |

| Total population |

| c. 23 million |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Morocco: 19,000,000 Algeria: |

| Languages |

| Berber (Tamazight) |

| Religions |

| Islam (overwhelming majority), atheism, Christianity, Judaism, Others |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Afro-Asiatic Semitic |

The Berbers (also called Amazigh people or Imazighen, "free men", singular Amazigh) are an ethnic group indigenous to Northwest Africa, speaking the Berber languages of the Afroasiatic family. In actuality, Berber is a generic name given to numerous heterogeneous ethnic groups that share similar cultural, political, and economic practices. It is not a term originated by the group itself, and indeed the word may have been derived from the Greek 'βάρβαρος', the forerunner of the English word 'barbarian'.

Amazigh & Berber

Historically, it is not clear how the name "Berber" evolved supposedly from the word "barbarian". Contrary to some sources, the "Berber/Imazighen" were not called "barbarians" by the Greeks or Romans. The Berbers were known as "Libyans" to the ancient Greeks, and they were known under many names, like "Numidians" and "Moors", to the Romans.

Due to the fact that the Berbers were called as "El-Barbar" by the Arabs, it is very probable that the modern European languages and the other ones adopted it from the Arabic language. The Arabs didn't use the name "El-Barbar" as a negative name, because the ancient Arab historians were not aware of the origin of that name; so, they supposedly created some myths or stories about the name. The most notorious myth considers "Barbar" as an ancestor of the Berbers. According to that myth, the Berbers were the descendants of Ham, the son of Noah, the son of Barbar, the son of Tamalla, the son of Mazigh, the son of Canon... [Ibn Khaldun/ The History of Ibn Khaldun - Chapter III].

The fact that the name "Berber" is a strange name to the Berbers led to confusion. Some sources claimed that the Berbers are several ethnic groups who are not related to each other. That is not accurate, because the Berbers refer to themselves as "Imazighen" in Morocco, as well as Libya, Egypt (Siwa) and other parts in North Africa.

Not only the origin of the name "Berber" is unclear, but also the name "Amazigh". The most common explanation is that the name goes back to the Egyptian period when the Ancient Egyptians mentioned an ancient Libyan tribe called Meshwesh. Those Meshwesh are supposed by some scholars to be the same ancient Libyan tribe that was mentioned as "Maxyans" by the Greek Historian Herodotus.

Libyans & Numidians

Both names, "Amazigh" and "Berber", are relatively recent names in historical sources, since the name "Berber" appeared first in Arab-islamic sources, and the name "Amazigh" was never used in ancient sources. It is no less important to keep in mind that the Berbers were known by various names in different periods.

The first reference to the Ancient Berbers goes back to a very ancient Egyptian period. They were mentioned in the pre-dynastic period, on the so-called " Stele of Tehenou" which is still preserved in the Cairo museum in Egypt. That tablet is considered to be the oldest source wherein the Berbers have been mentioned. The second source is known as The Stele of king Narmer. This tablet is newer than the first source, and it depicted the Tehenou as captives.

The second oldest name is Tamahou. This name was mentioned for the first time in the period of the first king of the "Sixth Dynasty" and was referred to in other sources after that period. According to Oric Bates, those people were white-skinned, blondish and with blue eyes.

Another important tribe was The Libou. This tribe was confusing for some scholars, because the name of this tribe emerges with the appearance of the so-called Sea People between the sixth and the fourth century B.C.E. Nevertheless, the Libou were not considered as "Sea People" but as indigenous people, and the emigrating people allied with them. The name "Libou" would later be used, by the Greeks, to refer to all the Berbers, and not only the modern North African country of Libya. [Mohammed Mustapha Bazma/ Libya: this name in the roots of the history]

In the Greek period the Berbers were mainly known as "The Libyans" and their lands as "Libya" that extended from modern Morocco to the western borders of ancient Egypt [Modern Egypt contains Siwa, part of historical Libya, that still speaks the Berber language].

During the Roman period, the Berbers would become known as Numidians, Maures and Getulians, according to their tribes or kingdoms. The Numidians founded complicated and organized tribes, and thereafter they began to build a stronger kingdom. Most scholars believe that "Alyamas" was the first king of the Numidian kingdom [Mohammed Chafik/ Highlights of thirty-three centuries of the history of Imazighen]. Massinissa was the most famous Numidian king, who made Numidia a strong and civilized kingdom.

The Berbers and their languages

(main article: Berber languages)

There are between 14 and 25 million speakers of Berber languages in North Africa, principally concentrated in Morocco and Algeria but with smaller communities as far east as Egypt and as far south as Burkina Faso.

Their languages, the Amazigh languages / Berber languages, form a branch of the Afroasiatic linguistic family comprising many closely related varieties, including Tarifit, Taqbaylit and Tashelhiyt, with a total of roughly 14-25 million speakers. A frequently used generic name for all Berber languages is Tamazight, not to be confused with the language found in the High and Middle Atlas or Rif.

Origin

There is no complete certitude about the origin of the Berbers; however, various disciplines shed light on the matter.

Genetic evidence

While population genetics is a young science still full of controversy, in general the genetic evidence appears to indicate that most northwest Africans (whether they consider themselves Berber or Arab) are predominantly of Berber origin, and that populations ancestral to the Berbers have been in the area since the Upper Paleolithic era. The genetically predominant ancestors of the Berbers appear to have come from East Africa, the Middle East, or both - but the details of this remain unclear. However, significant proportions of both the Berber and Arabized Berber gene pools derive from more recent migration of various Italic, Semitic, Germanic, and sub-Saharan African peoples, all of whom have left their genetic footprints in the region.

Archaeological

The Neolithic Capsian culture appeared in North Africa around 9,500 B.C.E. and lasted until possibly 2700 B.C.E. Linguists and population geneticists alike have identified this culture as a probable period for the spread of an Afro-Asiatic language (ancestral to the modern Berber languages) to the area. The origins of the Capsian culture, however, are archeologically unclear. Some have regarded this culture's population as simply a continuation of the earlier Mesolithic Ibero-Maurusian culture, which appeared around ~22,000 B.C.E., while others argue for a population change; the former view seems to be supported by dental evidence. [1]

Religions and beliefs

Berbers are predominantly Sunni Muslim, most belonging to the Maliki madhhab, while the Mozabites, Djerbans, and Nafusis of the northern Sahara are Ibadi Muslim. Sufi tariqas are common in the western areas, but rarer in the east; marabout cults were traditionally important in most areas.

Before their conversion to Islam, some Berber groups had converted to Christianity (often Donatist) or Judaism, while others had continued to practise traditional polytheism. See also Berber Jews.

Under the influence of Islamic culture, some syncretic religions briefly emerged, as among the Berghouata, only to be replaced by Islam.

History

The Berbers have lived in North Africa between western Egypt and the Atlantic Ocean for as far back as records of the area go. The earliest inhabitants of the region are found on the rock art across the Sahara. References to them also occur frequently in ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Roman sources. Berber groups are first mentioned in writing by the ancient Egyptians during the Predynastic Period, and during the New Kingdom the Egyptians later fought against the Meshwesh and Lebu (Libyans) tribes on their western borders. Many Egyptologists think that from about 945 B.C.E. the Egyptians were ruled by Meshwesh immigrants who founded the Twenty-second Dynasty under Shoshenq I, beginning a long period of Berber rule in Egypt, although others posit different origins for these dynasties, including Nubian ones. They long remained the main population of the Western Desert - the Byzantine chroniclers often complained of the Mazikes (Amazigh) raiding outlying monasteries there.

For many centuries the Berbers inhabited the coast of North Africa from Egypt to the Atlantic Ocean. Over time, the coastal regions of North Africa saw a long parade of invaders and colonists including Saharans, Phoenicians (who founded Carthage), Greeks (mainly in Libya), Romans, Vandals and Alans, Byzantines, Arabs, Ottomans, and the French and Spanish. Most if not all of these invaders have left some imprint upon the modern Berbers as have slaves brought from throughout Europe (some estimates place the number of Europeans brought to North Africa during the Ottoman period as high as 1.25 million)[2]. Interactions with neighboring Sudanic empires, sub-Saharan Africans, and nomads from East Africa also left vast impressions upon the Berber peoples.

In historical times, the Berbers expanded south into the Sahara (displacing earlier populations such as the Azer and Bafour), and have in turn been mainly culturally assimilated in much of North Africa by Arabs, particularly following the incursion of the Banu Hilal in the 11th century.

The areas of North Africa which retained the Berber language and traditions have, in general, been those least exposed to foreign rule—in particular, the highlands of Kabylie and Morocco, most of which even in Roman and Ottoman times remained largely independent, and where the Phoenicians never even penetrated beyond the coast. However, even these areas have been affected by some of the many invasions of North Africa, most recently including the French. Another major source of foreign influence, particularly in the Sahara, was the Trans-Atlantic slave trade route from West Africa, operated in part by the European commercial powers.

Berbers and the Islamic conquest

Unlike the conquests of previous religions and cultures, the coming of Islam, which was spread by Arabs, was to have pervasive and long-lasting effects on the Maghreb. The new faith, in its various forms, would penetrate nearly all segments of society, bringing with it armies, learned men, and fervent mystics, and in large part replacing tribal practices and loyalties with new social norms and political idioms.

Nonetheless, the Islamization and Arabization of the region were complicated and lengthy processes. Whereas nomadic Berbers were quick to convert and assist the Arab conquerors, not until the twelfth century, under the Almohad Dynasty, did the Christian and Jewish communities become totally marginalized.

The first Arab military expeditions into the Maghrib, between 642 and 669, resulted in the spread of Islam. These early forays from a base in Egypt occurred under local initiative rather than under orders from the central caliphate. When the seat of the caliphate moved from Medina to Damascus, however, the Umayyads (a Muslim dynasty ruling from 661 to 750) recognized that the strategic necessity of dominating the Mediterranean dictated a concerted military effort on the North African front. In 670, therefore, an Arab army under Uqba ibn Nafi established the town of Qayrawan about 160 kilometers south of present-day Tunis and used it as a base for further operations.

Abu al Muhajir Dinar, Uqba's successor, pushed westward into Algeria and eventually worked out a modus vivendi with Kusaila, the ruler of an extensive confederation of Christian Berbers. Kusaila, who had been based in Tilimsan (Tlemcen), became a Muslim and moved his headquarters to Takirwan, near Al Qayrawan.

This harmony was short-lived, however. Arab and Berber forces controlled the region in turn until 697. By 711, Umayyad forces helped by Berber converts to Islam had conquered all of North Africa. Governors appointed by the Umayyad caliphs ruled from Qayrawan, capital the new wilaya (province) of Ifriqiya, which covered Tripolitania (the western part of present-day Libya), Tunisia, and eastern Algeria.

Paradoxically, the spread of Islam among the Berbers did not guarantee their support for the Arab-dominated caliphate. The ruling Arabs alienated the Berbers by taxing them heavily; treating converts as second-class Muslims; and, at worst, by enslaving them. As a result, widespread opposition took the form of open revolt in 739-40 under the banner of Kharijite Islam. The Kharijites objected to Ali, the fourth caliph, making peace with the Umayyads in 657 and left Ali's camp (khariji means "those who leave"). The Kharijites had been fighting Umayyad rule in the East, and many Berbers were attracted by the sect's egalitarian precepts. For example, according to Kharijism, any suitable Muslim candidate could be elected caliph without regard to race, station, or descent from the Prophet Muhammad.

After the revolt, Kharijites established a number of theocratic tribal kingdoms, most of which had short and troubled histories. Others, however, like Sijilmasa and Tilimsan, which straddled the principal trade routes, proved more viable and prospered. In 750, the Abbasids, who succeeded the Umayyads as Muslim rulers, moved the caliphate to Baghdad and reestablished caliphal authority in Ifriqiya, appointing Ibrahim ibn al Aghlab as governor in Qayrawan. Although nominally serving at the caliph's pleasure, Al Aghlab and his successors, the Aghlabids, ruled independently until 909, presiding over a court that became a center for learning and culture.

Just to the west of Aghlabid lands, Abd ar Rahman ibn Rustam ruled most of the central Maghrib from Tahert, southwest of Algiers. The rulers of the Rustamid imamate, which lasted from 761 to 909, each an Ibadi Kharijite imam, were elected by leading citizens. The imams gained a reputation for honesty, piety, and justice. The court at Tahert was noted for its support of scholarship in mathematics, astronomy, and astrology, as well as theology and law. The Rustamid imams, however, failed, by choice or by neglect, to organize a reliable standing army. This important factor, accompanied by the dynasty's eventual collapse into decadence, opened the way for Tahert's demise under the assault of the Fatimids.

Modern-day Berbers

The Berbers live mainly in Morocco (between 35%-60% of the population) and in Algeria (about 15%-33% of the population), as well as Libya and Tunisia, though exact statistics are unavailable[3]; see Berber languages. Most North Africans who consider themselves Arab also have significant Berber ancestry[4]. Prominent Berber groups include the Kabyles of northern Algeria, who number approximately 4 million and have kept, to a large degree, their original language and culture; and the Chleuh (francophone plural of Arabic "Shalh" and Tashelhiyt "ašəlḥi") of south Morocco, numbering about 8 million. Other groups include the Riffians of north Morocco, the Chaouia of Algeria, and the Tuareg of the Sahara. There are approximately 3 million Berber immigrants in Europe, especially the Riffians and the Kabyles in the Netherlands and France. Some proportion of the inhabitants of the Canary Islands are descended from the aboriginal Guanches—usually considered to have been Berber—among whom a few Canary Islander customs, such as the eating of gofio, originated.

Although stereotyped in the West as nomads, most Berbers were in fact traditionally farmers, living in the mountains relatively close to the Mediterranean coast, or oasis dwellers; the Tuareg and Zenaga of the southern Sahara, however, were nomadic. Some groups, such as the Chaouis, practiced transhumance.

Political tensions have arisen between some Berber groups (especially the Kabyle) and North African governments over the past few decades, partly over linguistic and cultural issues; for instance, in Morocco, giving children Berber names was banned.

The Arabization of Northwest Africa

Before the 9th century, most of Northwest Africa was a Berber-speaking Muslim area. The process of Arabization only became a major factor with the arrival of the Banu Hilal, a tribe sent by the Fatimids of Egypt to punish the Berber Zirid dynasty for having abandoned Shiism. The Banu Hilal reduced the Zirids to a few coastal towns, and took over much of the plains; their influx was a major factor in the Arabization of the region, and in the spread of nomadism in areas where agriculture had previously been dominant.

Soon after independence, the countries of North Africa established Arabic as their official language, replacing French (except in Libya), although the shift from French to Arabic for official purposes continues even to this day. As a result, most Berbers had to study and know Arabic, and had no opportunities to use their mother tongue at school or university. This may have accelerated the existing process of Arabization of Berbers, especially in already bilingual areas, such as among the Chaouis.

Berberism had its roots before the independence of these countries, but was limited to some Berber elite. It only began to gain success when North African states replaced the colonial language with Arabic and identified exclusively as Arab nations, downplaying or ignoring the existence and the cultural specificity of Berbers. However, its distribution remains highly uneven. In response to its demands, Morocco and Algeria have both modified their policies, with Algeria redefining itself constitutionally as an "Arab, Berber, Muslim nation".

Currently, Berber is a "national" language in Algeria and is taught in some Berber speaking areas as a non-compulsory language. In Morocco, Berber has no official status, but is now taught as a compulsory language regardless of the area or the ethnicity.

Berbers are sometimes not discriminated against based on their ethnicity or mother tongue. As long as they share the reigning ideology, they can reach high positions in the social hierarchy; good examples are the former president of Algeria, Liamine Zeroual, and the current prime minister of Morocco, Driss Jettou. In Algeria, furthermore, Chaoui Berbers are over-represented in the Army for historical reasons.

Berberists who openly show their political orientations rarely reach high hierarchical positions. However, Khalida Toumi, a feminist and Berberist militant, has been nominated as head of the Ministry of Communication in Algeria.

Famous Berbers

In ancient times

- Shoshenq I, (Egyptian Pharaoh of Libyan origin)

- Masinissa, King of Numidia, North Africa, present day Algeria and Tunisia

- Jugurtha, King of Numidia

- Juba II, King of Numidia

- Terence, (full name Publius Terentius Afer), Roman writer

- Apuleius, Roman writer ("half-Numidian, half-Gaetulian")

- Tacfarinas, who fought the Romans in the Aures Mountains

- Saint Augustine of Hippo, (from Tagaste, was Berber)

- Saint Monica of Hippo, Saint Augustine's mother

- Arius, (who proposed the doctrine of Arianism)

- Donatus Magnus, (leader of the Donatist schism)

- Macrinus

In medieval times

- Dihya or al-Kahina

- Aksil or Kusaila

- Salih ibn Tarif of the Berghouata

- Tariq ibn Ziyad, one of the leaders of the Moorish conquest of Iberia in 711.

- Ibn Tumart, founder of the Almohad dynasty

- Yusuf ibn Tashfin, founder of the Almoravid dynasty

- Ibn Battuta (1304 - 1377), Moroccan traveller and explorer

- al-Ajurrumi (famous grammarian of Arabic)

- Fodhil al-Warthilani, traveler and religious scholar of the 1700s

- Abu Yaqub Yusuf I, who had the Giralda in Seville built.

- Abu Yaqub Yusuf II, who had the Torre del Oro in Seville built.

- Ziri ibn Manad founder of the Zirid dynasty

- Sidi Mahrez Tunisian saint

- Ibn Al Djazzar famous doctor of Kairouan, 980.

- Muhammad Awzal (ca. 1680-1749), prolific Sous Berber poet (see also Ocean of Tears)

- Muhammad al-Jazuli, author of the Dala'il al-Khairat, Sufi

In modern times

Politicians

- Saïd Sadi, secularist politician.

- Hocine Aït Ahmed, Algerian revolutionary fighter and secularist politician.

- Sidi Said, Leader of the Algerian syndicat of workers : UGTA.

- Khalida Toumi, Algerian feminist and secularist, currently spokesman of the Algerian government.

- Ahmed Ouyahia, Prime Minister of Algeria

- Belaïd Abrika, one of the spokesmen of the Arouch.

- Ferhat Mehenni, politician and singer who militates for the autonomy of Kabylie.

- Nordine Ait Hamouda, secularist politician and son of Colonel Amirouche.

- Saadeddine Othmani, deputy of Inezgane, an outer suburb of Agadir, is the leader of the Justice and Development Party (Islamist).

- Driss Jettou, Prime Minister of Morocco.

Figures of the Algerian resistance and revolution

- Abane Ramdane, Algerian revolutionary fighter, assassinated in 1957.

- Krim Belkacem, Algerian revolutionary fighter, assassinated in 1970.

- Colonel Amirouche, Algerian revolutionary fighter, killed by French troops in 1959.

- Lalla Fatma n Soumer, woman who led western Kabylie in battle against French colonizers.

Artists

- Takfarinas - Kabyle singer

- Ait Menguellet - Kabyle singer

- Khalid Izri - Singer from Rif

- Lounes Matoub, Berberist and secularist singer assassinated in 1998.

- Idir - Kabyle singer

- Igout Abdelhadi-Izenzarn Amazigh singer/musical group from Souss (south of Morocco).

- Fatima Tabaamrant- a singer and Amazigh activist in the Souss

- Haj Mohamed Demsiri- a singer from the Souss.

- Sliman Azem - singer

- Si Mohand, Kabyle folk poet.

- Souad Massi, a young, female Kabyle singer who performs mainly in French and Maghrebin Arabic.

- Aît Ouarab Mohamed Idir Halo (Al Anka), Chaabi singer in Both Kabyle and Algerian Arabic.

- Karim Ziad - singer

- El Hachemi Guerouabi, Chaabi Singer from Mostaghanem, North of algéria.

- Taos Amrouche, (March 4, 1913 in Tunis, Tunisia - April 2, 1976 in Saint-Michel-l'Observatoire, France) Algerian writer and singer.

- Rim-K, rapper

- Cheb-i-sabbah - DJ and composer in Algeria

Writers

- Mouloud Feraoun, writer assassinated by the OAS.

- Tahar Djaout, writer and journalist assassinated by the GIA in 1993.

- Salem Chaker, Berberist, linguist, cultural and political activist, writer, and director of Berber at the Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales in Paris

- Mouloud Mammeri, writer, anthropologist and linguist. His interest and work about Tamazight is behind the popular galvanization towards the Amazigh (Berber) culture and language.

- Taos Amrouche, (March 4, 1913 in Tunis, Tunisia - April 2, 1976 in Saint-Michel-l'Observatoire, France) Algerian writer and singer.

- Mohamed Chafiq, Moroccan writer and the dean of the IRCAM.

Sport

- Zinedine Zidane (1972 - ), French football superstar.

- Rabah Madjer, Algerian football superstar, Winner of the European Champion's League in 1987 with Porto FC

- Mustapha Hadji (1972 - ), Morrocan soccer player nominated best African player of the year 1998.

Others

- Abd el-Krim, leader of the Rif guerrillas against the Spanish and French colonizers.

- Walid Mimoun - Protest Singer from Rif

- Ali Lmrabet, Moroccan journalist.

- Kateb Yacine, Algerian Writer.

- Mohamed Choukri (famous writer)

- Liamine Zeroual, President of Algeria between 1994-1999.

- Mohamed Chafik

- Abdallah Oualline Berber Warrior & freedom fighter. Fought against the Spanish occupation in Ait Baamrane, south of Agadir.

- Didouche Mourad

- Cherif Khedam - composer

- Cheikh El Hasnaoui - singer

- Abdallah Nihrane -Scientific Investigator, Assistant Professor, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York USA

- Tinariwen - critically acclaimed band of Tuareg musicians

- M. Toufali - Writer and composer from the Rif (Melilla)

- Sawajiri Erika - Japanese actress. Japanese, Algerian-French mix.

Famous people who were either Berber or Punic

- Septimus Severus (Roman emperor from the mainly Punic Libyan city of Lepcis Magna, founded by Phoenicians)

- Caracalla, his son

- Tertullian, an early Christian theologian (born in the highly multiethnic, Phoenician-founded city of Carthage)

- Vibia Perpetua (early Christian martyr, also born in Carthage)

- Cyprian (also born in Carthage)

- Roos, Amirouche, Famous Swedish poet.

Famous people who may have had some Berber ancestors

Nearly all North Africans - and many Andalusi Moors - fall and fell into this category, but do not in general identify themselves as Berber. For lists of them, look under the respective countries.

See also

Template:CommonsCat

- Berber Jews

- Kabylie, a coastal Berber area, inhabited By Kabyles.

- Rif, a coastal Berber area, inhabited By Riffis.

- Zenata, ancestors of Riffis.

- Senhaja, ancestors of Souss Chleuhs.

- Masmouda, ancestors of Atlas Chleuhs

- Tuareg, a Saharan Berber group.

- Guanches, an indegenous people in the Canary Islands.

- Berber languages

- Barbary Coast

- Tamazgha, Berber name for North Africa.

- Berber pantheon

- Berber mythology

- Berberism

- Arabized Berber

- Moors

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brett, Michael; & Fentress, Elizabeth (1997). The Berbers (The Peoples of Africa). ISBN 0-631-16852-4. ISBN 0-631-20767-8 (Pbk).

- The Civilizations of Africa: A History to 1800 by Christopher Ehret

- Egypt In Africa by Celenko

- Stone Age Races of Northwest Africa by L. Cabot-Briggs

- The people of Africa (People of the world series) by Jean Hiernaux

- Britannica 2004

- Encarta 2005

- Blanc, S. H., Grammaire de la Langue Basque (d'apres celle de Larramendi), Lyons & Paris, 1854.

- Entwhistle, W. J. "The Spanish Language," (as cited in Michael Harrison's work, 1974.) London, 1936

- Gans Eric Lawrence, "The Origin of Language," Univ. of California Press, Berkeley, 1981.

- Geze, L., Elements de Grammaire Basque, Beyonne, 1873.

- Hachid, Malika, "Les Premiers Berberes" EdiSud, 2001

- Hagan, Helene E., "The Shining Ones: an Etymological Essay on the Amazigh Roots of Ancient Egyptian Civilisation." (XLibris, 2001)

- Hagan, Helene E. "Tuareg Jewelry: Traditional Patterns and Symbols," (XLibris, 2006)

- Harrison, Michael, "The Roots of Witchcraft," Citadel Press, Secaucus, N.J., 1974.

- Hualde, J. I., "Basque Phonology," Routledge, London & New York, 1991.

- Martins, J. P. de Oliveira, "A History of Iberian Civilization," Oxford University Press, 1930.

- Osborn, Henry Fairfield, "Men of the Old Stone Age," New York, 1915-1923.

- Renan, Ernest, De l'Origine du Langage, Paris, 1858; La Societe' Berbere, Paris, 1873.

- Ripley, W. Z., "The Races of Europe," D. Appleton & Co., New York, 1899.

- Ryan, William & Pitman, Walter, "Noah's Flood: The new scientific discoveries about the event that changed history," Simon & Schuster, New York, 1998.

- Saltarelli, M., "Basque," Croom Helm, New York, 1988.

- Silverstein, Paul A. "Algeria in France: Transpolitics, Race, and Nation," Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2004.

External links

- Richard L. Smith, Ferrum College, What Happened to the Ancient Libyans? Chasing Sources across the Sahara from Herodotus to Ibn Khaldun, Journal of World History, vol. 14, no. 4, 2003 Online article

- Amazigh Startkabel.

- Institut Royal de la Culture Amazighe.

- The New Mass Media and the Shaping of Amazigh Identity.

- Number Systems and Calendars of the Berber Populations of Grand Canary and Tenerife.

- Encyclopedia of the Orient — Berbers .

- Flags of the World — Berbers/Imazighen.

- www.mondeberbère.com.

- CMA: Congrès Mondial Amazigh.

- Photo Gallery of Berbers and Touregs from Erg Chebbi area of Moroccan Sahara

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.