Zerubbabel

Zerubbabel (Hebrew: ×ְרֻ×Ö¸Ö¼×Ö¶×, ZÉrubbÄvel; Greek: ζοÏοβαβελ, ZÅrobabel) was the leader of the first group of Jews, numbering 42,360, who returned from the Babylonian Captivity in the first year of Cyrus, King of Persia c. 538 B.C.E. He was a descendant of King David and grandson of Jehoiachin, the next-to-last king of Judah.

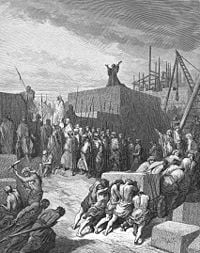

Although his dates are uncertain, Zerubbabel governed Judah for more than two decades. It was he who laid the foundation of the Second Temple in Jerusalem and ultimately supervised its completion after several delays.

Zerubbabel became an object of messianic hope for the prophets Haggai and Zechariah, who saw him as God's "signet ring" and anointed servant, before whom other kings would fall and mountains would crumble. He later became a figure of legend, as recorded in the apocryphal book of 1 Esdras and the Jewish Apocalypse of Zerubbabel.

Name and background

Zerubbabel was born during the period of Babylonian exile. If the name Zerubbabel is Hebrew, it may be a contraction of ZÉruaâ BÄvel (Hebrew: ×ְר×Ö¼×¢Ö· ×Ö¸Ö¼×Ö¶×), meaning "the one sown of Babylon," referring to a child conceived and born in Babylon. A similar meaning is derived from the name in Assyrian-Babylonian, since ZÉru BÄbel means "Seed of Babylon" in that language. It could also related to the Hebrew ZÉrûy BÄvel (Hebrew: ×ְר×Ö¼× ×Ö¸Ö¼×Ö¶×), meaning "the winnowed of Babylon," in the sense of the Jews having being "sifted" through their exile in Babylon.

Zerubbabel's grandfather Jehoiachin, also called Jeconiah, reigned in Jerusalem for only three months after replacing his father King Jehoiachim, who had died during the first Babylonian siege of Jerusalem. Still a teenager, Jehoiachin was removed from office by the army of King Nebuchadnezzar II and taken prisoner to Babylon. After 36 years in captivity, he was freed from prison by the Babylonian King Amel-Marduk.

The Bible lists Shealtiel as the son of Jehoiachin King Jeconiah (1 Chronicles 3:17) and the father of Zerubbabel (Ezra 3:2; 5:2; Nehemiah 12:1; Haggai 1:1, etc.) Shealtiel would have been a logical candidate as heir to the throne of Judah, if the Davidic line were restored. However, although the majority of the biblical references confirm Zerubbabel as Shealtiel's son, one text makes Zerubbabel Shealtiel's nephew (1 Chronicles 3:17-19) and the son of Pediah, Shealtiel's brother. Some speculate that the title "son of Shealtiel" does not refer to Zerubbabel as a biological son but to his being a member of Shealtiel's "house." Another explanation is the simplest: that the text which identifies Zerubbabel as a son of Pedaiah could be a scribal error. In any case, those texts that call Zerubbabel "son of Shealtiel" tend to emphasize Zerubbabel's potential claim to the Davidic throne as Shealtiel's successor.

Zerubbabel in Persia

A legend preserved in the apocryphal book of 1 Esdras describes the young Zerubbabel as one of the wisest men in the Persian Empire, in a story reminiscent of the prophet Daniel. According to chapter 3:1-5:3 of this work, Zerubbabel and two other young guardsmen-courtiers of King Dariusâagree to engage in a public dispute over the question of what is the strongest thing in the kingdom. The king approves of this contest and declares that the winner of the debate will receive great honor and royal favors.

The first contestant holds that wine is the strongest thing in the kingdom, because "it leads astray the minds of all who drink it. It makes equal the mind of the king and the orphan, of the slave and the free, of the poor and the rich." The second debater declares that men are the strongest, ruling over both land and sea; but he flatteringly adds that the king is even stronger, because "he is their lord and master, and whatever he says to them they obey." Zerubbabel then ironically argues that it is women who are strongest, since they give birth to men and kings alike, and men leave their mothers and fathers to serve women. He then adds that truth is even stronger than women: "The whole earth calls upon truth, and heaven blesses herâ¦. Truth endures and is strong for ever, and lives and prevails for ever and ever."

The king concurs with Zerubbabel and, at the young Jew's request, appoints him to lead a wave of Jewish exiles from Babylon to Jerusalem to complete the restoration of the Temple. Zerubbabel is also given sanction to return the sacred vessels that the king had preserved.

Zerubbabel in Jerusalem

Identity with Sheshbazzar?

The account of Zerubbabel's role in the return of the exiles to Jerusalem depends somewhat on whether or not he is identical with Sheshbazzar, "the prince of Judah" and leader of the first great band of exiles returning to Jerusalem from Babylon under Cyrus (Ezra 1:8). This, of course would render inaccurate the account of 1 Esdras that Zerubbabel returned under Darius I, but that is of little account since this section of 1 Esdras appears to be largely legendary and he is elsewhere listed as the leader of the first wave of returnees (Ezra 2:1). In any case, Zerubbabel was clearly regarded as the head of the community of returned exiles (Ezra 4:2) and he is associated in this capacity with the high priest Joshua in the general administration (Ezra 3:2, 8; 4:3; 5:2; Hag. 1 1; Zech. 3-4). He is described by the title of governor ("peḥah") of Judah by the prophet Haggai (1:1; 2:2), and this title is also given to Sheshbazzar by Ezra (5:14), apparently dealing with the same time period.

Some thus suppose that Zerubbabelâlike Daniel and the three young Hebrews who were his companionsâsimply bore two names, the Hebrew "Zerubbabel" and the Babylonian "Sheshbazzar." In opposition to this view it is pointed out this identity never specified in Ezra. It has been suggested that "Sheshbazzar" may be identical with "Shenazar" (I Chron. 3:18), one of the sons of Jehoiachin, and therefore an uncle of Zerubbabel. At all events, the Book of Ezra portrays him as the leader in charge of the early stages of Temple reconstruction during the reign of Cyrus, and the Book of Haggai makes it clear that Zerubbabel was still the "governor" of Judah in the second year of Darius I (520 B.C.E.), some 17 years after rebuilding had begun.

Activities

According to Ezra 3-4, Zerubbabel, together with the high priest Joshua (also called Jeshua) and others, erected an altar for burnt offerings in the seventh month after the return. There, they offered morning and evening sacrifices and kept the Feast of Tabernacles. In the second month of the second year they together laid the foundation of the Temple. They received an offer of aid by "the adversaries of Judah and Benjamin" (apparently northern Israelites of mixed Assyrian lineage, or converts to the worship of Yahweh), but Zerubbabel and Joshua rejected this aid on the grounds that it did not accord with Cyrus' instructions:

They came to Zerubbabel and to the heads of the families and said, "Let us help you build because, like you, we seek your God and have been sacrificing to him since the time of Esarhaddon king of Assyria, who brought us here." But Zerubbabel, Jeshua and the rest of the heads of the families of Israel answered, "You have no part with us in building a temple to our God. We alone will build it for the Lord, the God of Israel, as King Cyrus, the king of Persia, commanded us." (Ezra 4:2-3)

After this, the opposition of these "enemies" caused a delay of 17 years. Zerubbabel and Joshua were then aroused to fresh activity by the prophets Haggai and Zechariah. Work was thus resumed in the second year of Darius I (520 B.C.E.): "So the Lord stirred up the spirit of Zerubbabel son of Shealtiel, governor of Judah, and the spirit of Joshua son of Jehozadak, the high priest, and the spirit of the whole remnant of the people. They came and began to work on the house of the Lord Almighty, their God." (Haggai 1:14) Messianic fervor gripped the prophet as he spoke in God's name to Zerubbabel, promising that not even royal powers like those of Persia could stand against God's power:

"I will shake the heavens and the earth. I will overturn royal thrones and shatter the power of the foreign kingdoms. I will overthrow chariots and their drivers; horses and their riders will fall, each by the sword of his brother. On that day," declares the Lord Almighty, "I will take you, my servant Zerubbabel son of Shealtiel," declares the Lord, "and I will make you like my signet ring, for I have chosen you." (Haggai 2:21-23)

Similar sentiments were echoed by Haggai's contemporary, Zechariah, who seems to indicate Zerubbabel and Joshua to be the "two olive trees" he had seen in a vision representing the leaders "anointed" by God as his special servants in rebuilding the nation: "What are you, O mighty mountain? Before Zerubbabel you will become level ground... The hands of Zerubbabel have laid the foundation of this temple; his hands will also complete itâ¦. Men will rejoice when they see the plumb line in the hand of Zerubbabel." (Zech 4:7-14)

Zerubbabel, however, seems to have been more of a pragmatist. New obstacles were encountered in the suspicions of Tattenai, the Persian "governor beyond the river," and an appeal was made to Darius I, who promulgated a decree authorizing the completion of the work. The Temple was indeed finished and dedicated four years later (Ezra 5-6). The text does not specify whether Zerubbabel was present at its completion.

Legacy

Only after the Temple was completed did Ezra, as the agent of the Persian King Artaxerxes, arrive in Jerusalem and assume leadership. Nothing further is known with certainty of Zerubbabel. The twentieth century German theologian Ernst Sellin theorized that Zerubbabel was actually made king of Judah by his people, but was overthrown and put to death by the Persians. On the basis of the attitudes taken by Zechariah and Haggai and the fact that Zerubbabel was a Davidic descendant, Sellin believed that this kingdom was regarded at the time as messianic.

However, a rabbinical tradition says that Zerubbabel eventually returned to Babylon and died there. Although he succeeded in rebuilding the Temple, whatever messianic hopes the prophets of his day had in him were not fulfilled, at least not permanently.

Zerubbabel's sons are named in 1 Chron. 3:19. He achieved legendary status in post-exilic times, as evidenced by his story in 1 Esdras. He is mentioned in Ecclesiasticus (Sirach) (49:11-12) among the famous men of Israel: "How shall we magnify Zerubbabel? He was like a signet on the right hand, and so was Jeshua the son of Jozadak; in their days they built the house and raised a temple holy to the Lord, prepared for everlasting glory."

In Christian tradition, Zerubbabel is one of the ancestors of Jesus. In the New Testament, he is mentioned in the Gospel of Matthew's version of the genealogy of Jesus. He is again mentioned in the genealogy of Jesus recorded in the Gospel of Luke, where verse 3:27 records him as the son of Shealtiel.

Zerubbabel is portrayed as the receiver of a revelation in the seventh century Jewish Apocalypse of Zerubbabel, known in Hebrew as the Sefer Zerubbabel. He also plays a large role in the Yiddish writer Sholem Asch's final work, The Prophet (1955).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cully, Iris V., and Kendig Brubaker Cully. From Aaron to Zerubbabel: Profiles of Bible People. New York: Hawthorn Books, 1976. ISBN 978-0801560842

- Floyd, Michael H., and Robert D. Haak. Prophets, Prophecy, and Prophetic Texts in Second Temple Judaism. Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament studies, 427. New York: T & T Clark, 2006. ISBN 978-0567027801

- Horsley, Richard A. Scribes, Visionaries, and the Politics of Second Temple Judea. Louisville, Ky: Westminster John Knox Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0664229917

- Rose, Wolter H. "Zemah and Zerubbabel: Messianic Expectations in the Early Postexilic Period." Journal for the study of the Old Testament 304. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000. ISBN 978-1841270746

- Sacchi, Paolo, and Paolo Sacchi. "The History of the Second Temple Period." Journal for the study of the Old Testament 285. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000. ISBN 978-1850759386

This article incorporates text from the Jewish Encyclopedia, a work currently in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved June 13, 2023.

- Easton's Bible Dictionary: Zerubbabel

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Zerubbabel

- Loeb Family Tree: Zerubbabel

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.