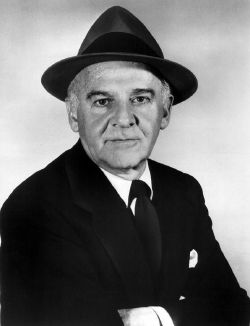

Walter Winchell

| Walter Winchell | |

Walter Winchell broadcasts during President Dwight D. Eisenhower's inaugural parade.

| |

| Born | April 7 1897 New York City, New York, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Died | February 20 1972 (aged 74) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

Walter Winchell (April 7, 1897 ‚Äď February 20, 1972) was an American newspaper and radio commentator. He invented the "gossip column" while at the New York Evening Graphic, ignoring the journalistic taboo against exposing the private lives of public figures and permanently altering journalism.

At the height of his influence, more than 50 million Americans, or two thirds of the adult population of the country, either read his daily column or listened to his weekly radio program. He was a supporter of the New Deal, supported civil rights and denounced Adolph Hitler and Fascism long before more Establishment journalists did.

Winchell's decline began when he embraced McCarthyism and he denounced singer Josephine Baker for saying she had been snubbed at his favorite club because she was black. Later in his life his personal behavior began to be defined by tantrums and shrill attacks on those who disagreed with him.

By legitimizing the use of gossip in the mainstream media Winchell paved the way for the contemporary celebrity obsessed culture. He was one of the most influential, colorful and controversial personalities of his day. As the first prominent journalist to break the cardinal rule of journalism, using unverified sources, he also became the father of a trend that has led American journalism to continually lose respect and credibility with the public.

Early life

He was born Walter Winschell on April 7, 1897, in New York City to Jacob Winschell and Jennie Bakst. He spent most of his early years in poverty and began working at a young age. He and two other boys put together a singing act called the Imperial Trio. At the age of 13 a vaudeville talent scout saw them perform and they were asked to join Gus Edwards' School Days, a song and dance act on the vaudeville circuit.

He eventually outgrew School Days and joined forces with another young vaudevillian, Rita Greene. They successfully toured the country and it was at this time that he began working on a vaudeville newsletter and sending articles to Billboard. He married Rita Greene and moved back to New York City, where he obtained a job writing for The Vaudeville News. He soon gained a reputation as Broadway's "man-about-town".[1]

Journalism career

He became a professional journalist when he began working for the New York Evening Graphic in 1924 as a columnist and drama critic. From there, he moved on to the New York Mirror. His unique "slanguage" writing style caught the public's attention, but it was his reporting on celebrities that made him famous.

Winchell's publications were extremely popular and influential for decades, notoriously aiding or harming the careers of many entertainers. Although he concentrated on gossiping about entertainment figures, Winchell frequently expressed opinions about public affairs.

By the 1930s, he was "an intimate friend of Owney Madden, New York's No. 1 gang leader of the prohibition era,"[2] His coverage of the Charles Lindbergh kidnapping and subsequent trial added to his fame. He also became the friend of J. Edgar Hoover, the No. 2 G-man of the repeal era. He became the intermediary for Louis "Lepke" Buchalter, of Murder, Inc., to turn himself over to Hoover.

His newspaper column was syndicated in over 2000 newspapers world-wide, and he was read by about 50 million people a day from the 1920s until the early 1960s. His Sunday night radio broadcast was heard by another 20 million people from 1930 to the late 1950s.

Political views

Winchell, who was Jewish, was one of the first commentators in America to attack Adolf Hitler and American pro-fascist and pro-Nazi organizations such as the German American Bund. He generally had a left-of-center political view through the 1930s and World War II, when he was stridently pro-Roosevelt, pro-labor, and pro‚ÄďDemocratic Party.

After World War II Winchell began to perceive Communism as the main threat facing America. A signal of Winchell's changed perspective was his wartime attack on the National Maritime Union, the labor organization for the civilian United States Merchant Marine, which he believed was run by Communists.[3] This evolution in Winchell's perspective continued after the war. During the late 1940s, he became allied with the right wing of American politics. In this new role, Winchell frequently attacked politicians he did not like by implying in his commentaries that they were Communist sympathizers.

During the 1950s Winchell favored Senator Joseph McCarthy, and as McCarthy's Red Scare tactics became more extreme, Winchell lost credibility along with McCarthy. He also had a weekly radio broadcast which was simulcast on ABC television until a dispute with ABC executives ended it in 1955.

A dispute with television personality Jack Paar is reputed to have played a role in ending Winchell's career and beginning a shift in power from print to television.[4] An attempt to revive his commentary program five years later was canceled after only six broadcasts.

NBC gave him the opportunity to host a variety show, which lasted only 13 weeks. His readership gradually dropped, and when his home paper, the New York Daily Mirror, for which he worked for 34 years, closed in 1963, he faded from the public eye.

He also received $25,000 an episode to narrate The Untouchables on the ABC television network for five seasons beginning in 1959. Winchell's highly recognizable voice lent credibility to the series, and his work as narrator is often better remembered today than his long-out-of-print newspaper columns.

Style

Winchell's success led to the emergence of other columnists, such as Ed Sullivan in New York and Louella Parsons in Los Angeles, who also began to write gossip. But Winchell had a style that others found impossible to mimic. He disdained the ornate style that had characterized newspaper columns in the past and instead wrote in a kind of telegraphic style filled with slang and incomplete sentences. Creating his own shorthand language, Winchell was responsible for introducing into the American vernacular such now-familiar words and phrases as scram, pushover, and belly laughs.[5] He wrote many quips such as "Nothing recedes like success". and "I usually get my stuff from people who promised somebody else that they would keep it a secret."

Winchell began his radio broadcasts by pressing randomly on a telegraph key, a sound which created a sense of urgency and importance. He then opened with the catch phrase "Good evening Mr. and Mrs. North and South America and all the ships at sea. Let's go to press." He would then read each of his stories with a rapid staccato delivery.

Winchell became a celebrity himself, often appearing as himself in movies. He frequented Sherman Billingsley's Stork Club during the 1940s, and always sat at Table 50 in the Cub Room. There was a Winchellburger on the menu.[6]

A less endearing aspect of Winchell's style were his attempts, especially after World War II, to destroy the careers of personal or political enemies: an example is the feud he had with New York radio host Barry Gray, whom he described as "Borey Pink" and a "disk jerk."[7] When Winchell heard that Marlen Edwin Pew of the trade journal Editor & Publisher had criticized him as a bad influence on the American press, he thereafter referred to him as "Marlen Pee-you."[2]

Winchell often did not have credible sources for his accusations. For most of his career his contract with his newspaper and radio employers required them to reimburse him for any damages he had to pay, should he be sued for slander or libel. Whenever friends reproached him for betraying confidences, he responded, "I know‚ÄĒ- I'm just a son of a bitch."[2] By the mid-1950s he was widely believed to be arrogant, cruel, and ruthless. The changes in Winchell's public image over time can be seen by comparing the two fictional movie gossip columnists who were based on Winchell. In the 1932 film, Okay, America, the columnist, played by Lew Ayres, is a hero. In the 1957 film, Sweet Smell of Success, the columnist, played by, Burt Lancaster, is obnoxious and mentally ill.

Personal life

On August 11, 1919, Winchell married Rita Green, one of his onstage vaudeville partners. The couple separated a few years later and he moved in with June Magee, who had already given birth to their first child, a daughter named Walda. Winchell and Green eventually divorced in 1928. Winchell and Magee never married, although the couple maintained the front of being married for the rest of their lives. Winchell feared that a marriage license would reveal the fact that Walda was illegitimate.

Winchell and Magee successfully kept the secret of their nonmarriage, but were struck by tragedy with all three of their children. Their adopted daughter Gloria died of pneumonia at age nine, and Walda spent time in mental institutions. Walter, Jr., the only son of the journalist, committed suicide in his family's garage on Christmas night, 1968.[8]

Later years

Winchell announced his retirement on February 5, 1969, citing the tragedy of his son's suicide as a major reason, while also noting the delicate health of Magee. Exactly one year later, she died at a Phoenix hospital while undergoing treatment for a heart condition.

Winchell's final two years were spent as a recluse at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, California. Larry King, who replaced Winchell at the Miami Herald, observed, "He was so sad. You know what Winchell was doing at the end? Typing out mimeographed sheets with his column, handing them out on the corner. That's how sad he got. When he died, only one person came to his funeral." (Several of Winchell's former co-workers expressed a willingness to go, but were turned back by his daughter Walda.)[9]

Winchell died of prostate cancer at the age of 74. Although his obituary appeared on the front page of The New York Times, his importance had long since ended.

Legacy

Winchell was inducted into the Radio Hall of Fame in 2004, 32 years after his death. During his lifetime, journalists, while acknowledging his pioneering role, were critical of his effect on the media. In 1940, Time Magazine St. Clair McKelway, who had written a New Yorker magazine series of articles on him, bemoaned, "the effect of Winchellism on the standards of the press." When Winchell began gossiping in 1924 for the tabloid Evening Graphic, no United States newspaper hawked rumors about the marital relations of public figures until they turned up in divorce courts. For 16 years following, gossip columns spread until even the staid New York Times whispered that it heard from friends of a son of the President that he was going to be divorced. In its first year, The Graphic would have considered this news not fit to print." Lamented McKelway, "Gossip-writing is at present like a spirochete in the body of journalism…. Newspapers… have never been held in less esteem by their readers or exercised less influence on the political and ethical thought of the times."[2] Winchell responded to McKelway saying, "Oh stop! You talk like a high-school student of journalism".[2]

Winchellism and Winchellese

The term "Winchellism" is named after him. Though its use is extremely rare and may be considered archaic, the term has two different usages.

- One definition is a pejorative judgment that an author's works are specifically designed to imply or invoke scandal and may be libelous.

- The other definition is ‚Äúany word or phrase compounded brought to the fore by the columnist Walter Winchell‚ÄĚ[10]or his imitators. Looking at his writing's effect on the language, an etymologist of his day said ‚Äúthere are plenty of ‚Ķ expressions which he has fathered and which are now current among his readers and imitators and constitute a flash language which has been called Winchellese. Through a newspaper column which has nation-wide circulation, Winchell has achieved the position of dictator of contemporary slang.‚ÄĚ[11] Winchell invented his own phrases that were viewed as slightly racy at the time. Some of the expressions for falling in love used by Winchell were: ‚Äúpashing it,‚ÄĚ ‚Äúsizzle for,‚ÄĚ ‚Äúthat way, go for each other,‚ÄĚ ‚Äúgarbo-ing it,‚ÄĚ ‚Äúuh-huh‚ÄĚ; and in the same category, ‚Äúnew Garbo, trouser-crease-eraser,‚ÄĚ and ‚Äúpash.‚ÄĚ Some Winchellisms for marriage are: ‚Äúmiddle-aisle it,‚ÄĚ ‚Äúaltar it,‚ÄĚ ‚Äúhandcuffed,‚ÄĚ ‚ÄúMendelssohn March,‚ÄĚ ‚Äú‚ÄúLohengrin it,‚ÄĚ and ‚Äúmerged‚ÄĚ.[11].

In popular culture

- Robert A. Heinlein coined the term "Winchell" as a generic description for a politically active gossip columnist. His 1961 novel Stranger in a Strange Land features a major character (Ben Caxton) who is a winchell. Heinlein coined as a contrasting term, "lippmann," in reference to journalist Walter Lippmann, a contemporary of Winchell's.

- Winchell is the real identity of Eddie Gretchen, the narrator of "Blabbermouth"‚ÄĒa 1941 (published 1947) story by Theodore Sturgeon.

- In The Producers musical Leo Bloom sings, "I'm gonna put on shows that will enthrall 'em / Read my name in Winchell's column" during I Wanna Be a Producer.

- The Cole Porter composition Let's Fly Away, includes the lines "Let's fly away/ And find a land that's so provincial/ We'll never hear what Walter Winchell/ Might be forced to say."

- Winchell is mentioned in Billy Joel's historically themed song We Didn't Start the Fire, in the verse chronicling 1949.

- P. G. Wodehouse's short story "The Rise of Minna Nordstrom," portrays Winchell, thinly concealing his identity under the name "Waldo Winkler."

- Damon Runyon's character Waldo Winchester in the short story "Romance in the Roaring Forties," is based on Walter Winchell. On the subject of this story, Damon Runyon, Jr. comments in his memoir Father's Footsteps: "I leave it to a realist like Walter Winchell to say whether what happens to the character is true."

- Author Michael Herr wrote Walter Winchell - A Novel in 1990.

- Several versions of "The Lady Is a Tramp" features the lyric "why she reads Walter Winchell and understands every line." Ella Fitzgerald sings the lyric as, "I follow Winchell and read every line" - a slight to society women who presumably scan the column only for mentions of their own names.)

- In Clare Boothe Luce's The Women, the character of Sylvia Fowler defends that she doesn't know for whom her husband has left her: "Nobody knows, not even Winchell."

- Shellac quote Winchell's catchphrase, "Mr and Mrs America, and all the ships at sea." in their song "The End of Radio."

- Harry Warren and Al Dubin mention Winchell in the song "Shuffle Off to Buffalo" from the movie 42nd Street: "Some day, I hope we'll be elected/To buy a lot of baby clothes/We don't know when to expect it/But it's a cinch that Winchell knows."

- In an episode of M*A*S*H, Colonel Potter refers to Corporal Klinger as "Walter Winchell" for talking loudly about Father Mulcahy's prospective promotion

- In the movie American Me, Walter Winchell is mentioned, along with the Hearst newspapers, as contributing to the public's anger towards Zoot Suiters in Los Angeles.

- In the book The Plot Against America, author Philip Roth uses Winchell as one of its main supporting characters in a fiction that has Winchell as a Democratic candidate to succeed Charles Lindbergh as president of the United States.

- Mentioned in passing in the Ian Fleming novel Live and Let Die.

- Walter Winchell is referenced in the names of two weatherman, Walter Parker and Bruch Winchell, in the Nickelodeon series Drake & Josh.

- Burt Lancaster's role as J.J. Hunsecker in the 1957 film noir, Sweet Smell of Success was based on the famed columnist.

- Lee Tracy's character of Alvin in the 1932 film Blessed Event, was based on Winchell.

- Walter Winchell was portrayed by Craig T. Nelson in The Josephine Baker Story, noted as accepting her upon her return to America from France but later turning against her for being a European sympathizer.

- Caricatured (as Walter Windpipe) in the 1936 Merrie Melodies short "The Coo-Coo Nut Grove"

- Irving Berlin's song "Cheer for the Navy," included in "This is the Army" musical (1943), reads "The Army may be in the groove but Walter Winchell won't approve unless you give a cheer for the Navy."

In media

Shows set in the American entertainment world of the 1930s, 1940s, or 1950s often feature Walter Winchell. The following actors portrayed Winchell:

- The 1932 film Okay, America is based on Winchell's life.

- Joey Forman in 1980 TV movie, The Scarlett O'Hara War.

- Craig T. Nelson in 1991 movie, The Josephine Baker Story.

- Joseph Bologna in the 1992 HBO movie, Citizen Cohn.

- Michael Townsend Wright in the 1998 TV movie, The Rat Pack.

- Stanley Tucci in the 1998 HBO biopic Winchell.

- Mark Zimmerman in the 1999 TV movie, Dash and Lilly.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ National Broadcasters Hall of Fame Infoage.org. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 TIME magazine review of Gossip: the Life and Times of Walter Winchell Time.com. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ "Liberty Ships" 1995 Public Broadcasting System (PBS) documentary

- ‚ÜĎ Pioneers of Television: "Late Night" episode (2008 PBS mini-series) Paar's feud with newspaper columnist Walter Winchell marked a major turning point in American media power. No one had ever dared criticize Winchell, because a few lines in his column could destroy a career, but when Winchell disparaged Paar in print, Paar fought back and mocked Winchell repeatedly on the air. Paar's criticisms effectively ended Winchell's career. The tables had turned, now TV had the power.

- ‚ÜĎ Paul Sann. 1971. Kill the Dutchman! The story of Dutch Schultz. (New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House. ISBN 0870001094)

- ‚ÜĎ Ralph Blumenthal, 2000. The Stork Club Thecityreview.com. Retrieved November 16, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Feud Days Time.com. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Walter Winchell Imbd.com. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Neal Gabler. Winchell: Gossip, Power, and the Culture of Celebrity. (New York: Vintage Press, 1995), 3

- ‚ÜĎ J. Louis Kuethe, "John Hopkins Jargon." American Speech 7 (5)(Jun., 1932): 327‚Äď338

- ‚ÜĎ 11.0 11.1 Paul Robert Beath, "Winchellese." American Speech 7 (1) (Oct., 1931): 44‚Äď46

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gabler, Neal. 1994. Winchell: Gossip, Power, and the Culture of Celebrity. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0679417516.

- Kuethe, J. Louis, "John Hopkins Jargon." American Speech 7 (5)(Jun., 1932): 327‚Äď338.

- Klurfeld, Herman. 1976. Winchell, His Life and Times. New York: Praeger. ISBN 0275337200.

- McKELWAY, ST. CLAIR. GOSSIP: The Life and Time Of Walter Winchell. New York: The Viking Press, 1940.

- Mosedale, John. 1981. The Men who Invented Broadway: Damon Runyon, Walter Winchell & Their World. New York, NY: R. Marek Publishers. ISBN 0399900853.

- Sann, Paul. 1971. Kill the Dutchman! The story of Dutch Schultz. New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House. ISBN 0870001094.

- Stuart, Lyle. The Secret Life Of Walter Winchell. (1953) Kessinger reprint ed., 2007. ISBN 0548387257.

- Winchell, Walter. 1975. Winchell Exclusive. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0139602860.

External links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

- Walter Winchell Imbd.com.

- A remembrance by a contemporary Evesmag.com.

- Walter Winchell Doney.net

- 15 Terms Popularized by Walter Winchell People.howstuffworks.com.

- WWII News 1941-05-18 Walter Winchell Archive.org.

- Weinraub, Bernard. 1998. He Turned Gossip Into Tawdry Power; Walter Winchell, Who Climbed High and Fell Far, Still Scintillates Query.nytimes.com.

- Paar vs. Winchell Slate.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.