Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh (March 30, 1853 – July 29, 1890) is one of the world's best known and most beloved artists. He is perhaps as widely known for being a madman and cutting off his own earlobe as he is for being a great painter. He spent his youth mainly in Holland. Before he dedicated himself to becoming a painter, he worked in various fields; including art dealing, preaching, and teaching. As a painter Van Gogh was a pioneer of Expressionism. He produced all of his work, some 900 paintings and 1100 drawings, during the last ten years of his life and most of his best-known work was produced in the final two years of his life. His art became his religious calling after various frustrations in trying to follow the traditional path to becoming a clergyman. Following his death, his fame grew slowly, helped by the devoted promotion of his widowed sister-in-law.

A central figure in Vincent van Gogh's life was his brother Theo, an art dealer with the firm of Goupil & Cie, who continually provided financial support. Their lifelong friendship is documented in numerous letters they exchanged from August 1872 onwards, which were published in 1914. Vincent's other relationships, with women especially, were less stable. Vincent never married nor had any children.

Biography

Early life (1853 - 1869)

Vincent Willem van Gogh was born in Zundert in the Province of North Brabant, in the southern Netherlands, the son of Anna Cornelia Carbentus and Theodorus van Gogh, a Protestant minister. He was given the same name as his first brother, who had been born exactly one year before Vincent and had died within a few hours of birth. His brother Theodorus (Theo) was born on May 1, 1857. He also had another brother named Cor and three sisters, Elisabeth, Anna and Wil. As a child, Vincent was serious, silent and thoughtful. In 1860 he attended Zundert village school in a class of 200. From 1861 he and his sister Anna were taught at home by a governess until October 1, 1864. At this point he went away to the elementary boarding school of Jan Provily in Zevenbergen, about 20 miles away. He was distressed to leave his family home, and recalled this even in adulthood. On September 15, 1866, he went to the new middle school, "Rijks HBS Koning Willem II", in Tilburg. Here Vincent was taught drawing by Constantijn C. Huysmans, who had himself achieved some success in Paris. In March 1868 Van Gogh abruptly left school and returned home. In recollection, Vincent wrote: "My youth was gloomy and cold and barren…" [1]

Art dealer and preacher (1869 - 1878)

In July 1869, at the age of 16, Vincent van Gogh was given a position as an art dealer by his uncle Vincent. He originally worked for Goupil & Cie in The Hague, but was transferred in June, 1873, to work for the firm in London. He himself stayed in Stockwell. Vincent was successful at work and was earning more than his father.[2] He fell in love with his landlady's daughter, Eugénie Loyer[3], but when he finally confessed his feeling to her she rejected him, saying that she was already secretly engaged to a previous lodger.

Vincent became increasingly isolated and fervent about religion. His father and uncle dispatched him to Paris, where he became resentful at treating art as a commodity and communicated this to the customers. On April 1, 1876, it was agreed that his employment should be terminated. He became very emotionally involved in his religious interests and returned to England to volunteer as a supply teacher in a small boarding school in Ramsgate. The proprietor of the school eventually relocated, and Vincent then became an assistant for a nearby Methodist preacher.

At Christmas that year he returned home and began working in a bookshop in Dordrecht. He was not happy in this new position and spent most of his time in the back of the shop on his own projects.[4] Vincent's diet was frugal and mostly vegetarian. In May 1877, in an effort to support his wish to become a pastor, his family sent him to Amsterdam where he lived with his uncle Jan van Gogh.[5] Vincent prepared for university, studying for the theology entrance exam with his uncle Johannes Stricker, a respected theologian. Vincent failed at his studies and had to abandon them. He left uncle Jan's house in July 1878. He then studied, but failed, a three-month course at a Brussels missionary school, and returned home, yet again in despair.

Borinage and Brussels (1879 - 1880)

In January 1879 Van Gogh got a temporary post as a missionary in the village of Petit Wasmes [6] in the coal-mining district of Borinage in Belgium. Van Gogh took his Christian ideals seriously, wishing to live like the poor and share their hardships to the extent of sleeping on straw in a small hut at the back of the baker's house where he was billeted;[7] the baker's wife used to hear Vincent sobbing all night in the little hut.[8] His choice of squalid living conditions did not endear him to the appalled church authorities, who dismissed him for "undermining the dignity of the priesthood." After this he walked to Brussels,[9] returned briefly to the Borinage, to the village of Cuesmes, but acquiesced to pressure from his parents to come 'home' to Etten. He stayed there until around March the following year,[10] to the increasing concern and frustration of his parents. There was considerable conflict between Vincent and his father, and his father made inquiries about having his son committed to a lunatic asylum[11] at Geel.[12] Vincent fled back to Cuesmes where he lodged with a miner named Charles Decrucq[13] until October. He became increasingly interested in the everyday people and scenes around him, which he recorded in drawings.

In 1880, Vincent followed the suggestion of his brother Theo and took up art in earnest. In autumn 1880, he went to Brussels, intending to follow Theo's recommendation to study with the prominent Dutch artist Willem Roelofs, who persuaded Van Gogh (despite his aversion to formal schools of art) to attend the Royal Academy of Art.

Return to Etten (1881)

In April 1881, Van Gogh again went to live with his parents in Etten and continued drawing, using neighbors as subjects. Through the summer he spent much time walking and talking with his recently widowed cousin, Kee Vos-Stricker.[14] Kee was seven years older than Vincent, and had an eight-year-old son. Vincent proposed marriage, but she flatly refused with the words: "No. Never. Never." (niet, nooit, nimmer)[15] At the end of November he wrote a strong letter to Uncle Stricker,[16] and then, very soon after, hurried to Amsterdam where he talked with Stricker again on several occasions,[17] but Kee refused to see him at all. Her parents told him "Your persistence is 'disgusting'."[18] In desperation he held his left hand in the flame of a lamp, saying, "Let me see her for as long as I can keep my hand in the flame."[19] He did not clearly recall what happened next, but assumed that his uncle blew out the flame. Her father, "Uncle Stricker," as Vincent refers to him in letters to Theo, made it clear that there was no question of Vincent and Kee marrying, given Vincent's inability to support himself financially.[20] What he saw as the hypocrisy of his uncle and former tutor affected Vincent deeply. At Christmas he quarreled violently with his father, refused any financial help, and immediately left for the Hague.[21]

The Hague and Drenthe (1881 - 1883)

In January 1882 he left for the Hague, where he called on his cousin-in-law, the painter Anton Mauve, who encouraged him towards painting. Mauve appeared to go suddenly cold towards Vincent, not returning a couple of his letters. Vincent guessed that Mauve had learned of his new domestic relationship with the alcoholic prostitute, Clasina Maria Hoornik (known as Sien) and her young daughter.[22] Sien had a five-year-old daughter, and was pregnant. On July 2, Sien gave birth to a baby boy, Willem.[23] When Vincent's father discovered this relationship, considerable pressure was put on Vincent to abandon Sien and her children.[24] Vincent was at first defiant in the face of his family's opposition.

His uncle Cornelis, an art dealer, commissioned 20 ink drawings of the city from him; they were completed by the end of May[25]. In June Vincent spent three weeks in hospital suffering gonorrhea[26] In the summer, he began to paint in oil.

In autumn 1883, after a year with Sien, he abandoned her and the two children. Vincent had thought of moving the family away from the city, but in the end he made the break. He moved to the Dutch province of Drenthe and in December, driven by loneliness, he once again opted to stay with his parents who were by then living in Nuenen, also in the Netherlands.

Nuenen (1883 - 1885)

In Nuenen, he devoted himself to drawing, paying boys to bring him birds' nests[27] and rapidly[28] sketching the weavers in their cottages.

In autumn 1884, a neighbor's daughter, Margot Begemann, ten years older than Vincent, accompanied him constantly on his painting forays and fell in love, which he reciprocated (though less enthusiastically). They agreed to marry, but were opposed by both families. Margot tried to kill herself with strychnine and Vincent rushed her to hospital.[29]

On March 26, 1885, Van Gogh's father died of a stroke. Van Gogh grieved deeply. At about the same time there was interest from Paris in some of his work. In the spring he painted what is now considered his first major work, The Potato Eaters (Dutch De Aardappeleters). In August his work was exhibited for the first time, in the windows of a paint dealer, Leurs, in the Hague.

Antwerp (1885 - 1886)

In November 1885 he moved to Antwerp and rented a little room above a paint dealer's shop in the Rue des Images.[30] He had little money and ate poorly, preferring to spend what money his brother Theo sent to him on painting materials and models. Bread, coffee, and tobacco were his staple intake. In February 1886 he wrote to Theo saying that he could only remember eating six hot meals since May of the previous year. His teeth became loose and caused him much pain.[31] While in Antwerp he applied himself to the study of color theory and spent time looking at work in museums, particularly the work of Peter Paul Rubens, gaining encouragement to broaden his palette to carmine, cobalt and emerald green. He also bought some Japanese woodblocks in the docklands.

In January 1886 he matriculated at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Antwerp, studying painting and drawing. Despite disagreements over his rejection of academic teaching, he nevertheless took the higher level admission exams. For most of February he was ill, run down by overwork and a poor diet (and excessive smoking).

Paris (1886 - 1888)

In March 1886 he moved to Paris to study at Cormon's studio. For some months Vincent worked at Cormon's studio where he met fellow students, Émile Bernard and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who used to frequent the paint store run by Julien "Père" Tanguy, which was at that time the only place to view works by Paul Cézanne.

At the turn of 1886 to 1887 Theo found shared life with Vincent "almost unbearable," but in spring 1887 they made peace. Vincent then became acquainted with Paul Signac, a follower of Georges Seurat. Vincent and his friend Emile Bernard, who lived with parents in Asnières, adopted elements of the "pointillé" (pointillism) style, where many small dots are applied to the canvas, resulting in an optical blend of hues, when seen from a distance. The theory behind this also stresses the value of complementary colors in proximity—for example, blue and orange—as such pairings enhance the brilliance of each color by a physical effect on the receptors in the eye.

In November 1887, Theo and Vincent met and befriended Paul Gauguin, who had just arrived in Paris.[32] In 1888, when the combination of Paris life and shared accommodation with his brother proved excessive for Vincent's nerves, he left the city, having painted over 200 paintings during his two years there.

Arles (February 1888 - May 1889)

He arrived on February 21, 1888, at the Hotel Carrel in Arles. He had fantasies of founding a Utopian colony of artists. His companion for two months was the Danish artist, Christian Mourier-Petersen. In March, he painted local landscapes, using a gridded "perspective frame." Three of his pictures were shown at the Paris Salon des Artistes Indépendents. In April he was visited by the American painter, Dodge MacKnight, who was residing in nearby Fontvieille.

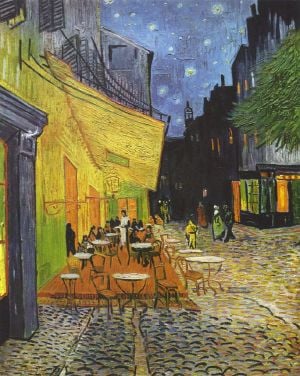

On May 1, he signed a lease for 15 francs a month to rent the four rooms in the right hand side of the "Yellow House" (so called because its outside walls were yellow) at No. 2 Place Lamartine. The house was unfurnished and had been uninhabited for some time so he was not able to move in straight away. He had been staying at the Hôtel Restaurant Carrel in the Rue de la Cavalerie. On May 7 he moved out of the Hôtel Carrel, and moved into the Café de la Gare.[33] He became friends with the proprietors, Joseph and Marie Ginoux. Although the Yellow House had to be furnished before he could fully move in, Van Gogh was able to use it as a studio.[34] Gauguin agreed to join him in Arles.

On September 8, upon advice from his friend Joseph Roulin, the station's postal supervisor, he bought two beds,[35] and he finally spent the first night in the still sparsely furnished Yellow House on September 17.[36]

On October 23 Gauguin arrived in Arles, after repeated requests from Van Gogh. During November they painted together. Uncharacteristically, Van Gogh painted some pictures from memory, deferring to Gauguin's ideas on this.

In December the two artists visited Montpellier and viewed works by Courbet and Delacroix in the Museé Fabre. However, their relationship was deteriorating badly. They quarreled fiercely about art. Van Gogh felt an increasing fear that Gauguin was going to desert him, and what he described as a situation of "excessive tension" reached a crisis point on December 23, 1888, when Van Gogh stalked Gauguin with a razor and then cut off the lower part of his own left ear, which he wrapped in newspaper and gave to a prostitute called Rachel in the local brothel, asking her to "keep this object carefully."[37]

An alternative account of the ear incident has been presented by two German art historians who have suggested that it was Gauguin who sliced off Van Gogh's ear with his sword during a fight. They further suggest that the two agreed not to reveal the truth, although Van Gogh hinted at such a possibility in letters to Theo.[38]

Gauguin left Arles and did not speak to Van Gogh again. Van Gogh was hospitalized and in a critical state for a few days. He was immediately visited by Theo (whom Gauguin had notified), as well as Madame Ginoux and frequently by Roulin.

In January 1889 Van Gogh returned to the "Yellow House," but spent the following month between hospital and home, suffering from hallucinations and paranoia that he was being poisoned. In March the police closed his house, after a petition by 30 townspeople, who called him fou roux ("the redheaded madman"). Signac visited him in the hospital and Van Gogh was allowed home in his company. In April he moved into rooms owned by Dr. Rey, after floods damaged paintings in his own home.

Saint-Rémy (May 1889 - May 1890)

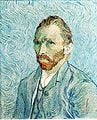

On May 8, 1889, Van Gogh was admitted to the mental hospital of Saint-Paul-de Mausole in a former monastery in Saint Rémy de Provence, a little less than 20 miles from Arles. Theo van Gogh arranged for his brother to have two small rooms, one for use as a studio, although in reality they were simply adjoining cells with barred windows.[39] In September 1889 he painted a self portrait, Portrait de l'Artiste sans Barbe that showed him without any beard. This painting sold at auction in New York in 1998 for US $71,500,000. Because of the shortage of subject matter due to his limited access to the outside world, he painted interpretations of Jean Francois Millet's paintings, as well copies as his own earlier work.

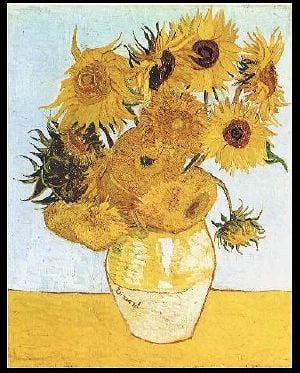

In January 1890, his work was praised by Albert Aurier in the Mercure de France, and he was called a genius. In February, invited by Les XX, a society of avant-garde painters in Brussels, he participated in their annual exhibition. When, at the opening dinner, Van Gogh's works were insulted by Henry de Groux, a member of Les XX, Toulouse-Lautrec demanded satisfaction, and Signac declared, he would continue to fight for Van Gogh's honor, if Lautrec should be surrendered. Later, when Van Gogh's exhibit was on display, including two versions of his Sunflowers and Wheat Fields, Sunrise with the gallery called Artistes Indépendants in Paris, Claude Monet said that his work was the best in the show. [40]

Auvers-sur-Oise (May - July 1890)

In May 1890, Vincent left the clinic and went to the physician Dr. Paul Gachet, in Auvers-sur-Oise near Paris, where he was closer to his brother Theo. Van Gogh's first impression was that Gachet was "sicker than I am, I think, or shall we say just as much."[41] Later Van Gogh did two portraits of Gachet in oils; one hangs at Musée d'Orsay in Paris, as well as a third - his only etching, and in all three emphasis is on Gachet's melancholic disposition.

Van Gogh's depression deepened, and on July 27, 1890, at the age of 37, he walked into the fields and shot himself in the chest with a revolver. Without realizing that he was fatally wounded, he returned to the Ravoux Inn, where he died in his bed two days later. Theo hastened to be at his side and reported his last words as "La tristesse durera toujours" (French for "the sadness will last forever"). He was buried at the cemetery of Auvers-sur-Oise.

Theo, not long after Vincent's death, was himself hospitalized. He was not able to come to terms with the grief of his brother's absence, and died six months later on January 25 at Utrecht. In 1914 Theo's body was exhumed and re-buried beside Vincent's.

Work

Van Gogh drew and painted with watercolors while at school, however few survive and authorship is challenged on some of those that do.[42] When he committed to art as an adult, he began at an elementary level, copying the Cours de dessin, a drawing course edited by Charles Bargue. Within two years he had begun to seek commissions. In spring 1882, his uncle, Cornelis Marinus, owner of a well-known gallery of contemporary art in Amsterdam, asked him for drawings of the Hague. Van Gogh's work did not live up to his uncle's expectations. Marinus offered a second commission, this time specifying the subject matter in detail, but was once again disappointed with the result. Nevertheless, Van Gogh persevered. He improved the lighting of his studio by installing variable shutters and experimented with a variety of drawing materials. For more than a year he worked on single figures – highly elaborated studies in "Black and White,"[43] which at the time gained him only criticism. Today, they are recognized as his first masterpieces.[44]

Olive Trees with the Alpilles in the Background, 1889, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Early in 1883, he began to work on multi-figure compositions, which he based on his drawings. He had some of them photographed, but when his brother remarked that they lacked liveliness and freshness, he destroyed them and turned to oil painting. By Autumn 1882, his brother had enabled him financially to turn out his first paintings, but all the money Theo could supply was soon spent. Then, in spring 1883, Van Gogh turned to renowned Hague School artists like Weissenbruch and Blommers, and received technical support from them, as well as from painters like De Bock and Van der Weele, both second generation Hague School artists. When he moved to Nuenen after the intermezzo in Drenthe he began a number of large-sized paintings but destroyed most of them. The Potato Eaters and its companion pieces – The Old Tower on the Nuenen cemetery and The Cottage – are the only ones to have survived. Following a visit to the Rijksmuseum, Van Gogh was aware that many of his faults were due to lack of technical experience. So in November 1885 he traveled to Antwerp and later to Paris to learn and develop his skill.

After becoming familiar with Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist techniques and theories, Van Gogh went to Arles to develop on these new possibilities. But within a short time, older ideas on art and work reappeared: ideas such as working with serial imagery on related or contrasting subject matter, which would reflect on the purposes of art. As his work progressed, he painted many Self-portraits. Already in 1884 in Nuenen he had worked on a series that was to decorate the dining room of a friend in Eindhoven. Similarly in Arles, in spring 1888 he arranged his Flowering Orchards into triptychs, began a series of figures that found its end in The Roulin Family series, and finally, when Gauguin had consented to work and live in Arles side-by-side with Van Gogh, he started to work on The Décorations for the Yellow House. Most of his later work is involved with elaborating on or revising its fundamental settings. In the spring of 1889, he painted another, smaller group of orchards. In an April letter to Theo, he said, "I have 6 studies of Spring, two of them large orchards. There is little time because these effects are so short-lived."[45]

Art historian Albert Boime believes that Van Gogh – even in seemingly fantastical compositions like Starry Night – based his work in reality.[46] The White House at Night, shows a house at twilight with a prominent star surrounded by a yellow halo in the sky. Astronomers at Southwest Texas State University in San Marcos calculated that the star is Venus, which was bright in the evening sky in June 1890 when Van Gogh is believed to have painted the picture.[47]

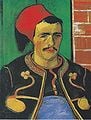

Self portraits

Self-portrait without beard, end September 1889, (F 525), Oil on canvas, 40 × 31 cm., Private collection. This was Van Gogh's last self portrait, given as a birthday gift to his mother.[48]

Van Gogh created many self-portraits during his lifetime. He was a prolific self-portraitist, who painted himself 37 times between 1886 and 1889.[49] In all, the gaze of the painter is seldom directed at the viewer; even when it is a fixed gaze, he appears to look elsewhere. The paintings vary in intensity and color and some portray the artist with beard, some beardless, some with bandages – depicting the episode in which he severed a portion of his ear. Self-portrait Without Beard, from late September 1889, is one of the most expensive paintings of all time, selling for $71.5 million in 1998 in New York.[50] At the time, it was the third (or an inflation-adjusted fourth) most expensive painting ever sold. It was also Van Gogh's last self-portrait, given as a birthday gift to his mother.[48]

All of the self-portraits painted in Saint-Rémy show the artist's head from the right, the side opposite his mutilated ear, as he painted himself reflected in his mirror.[51][52] During the final weeks of his life in Auvers-sur-Oise, he produced many paintings, but no self-portraits, a period in which he returned to painting the natural world.[53]

Portraits

Although Van Gogh is best known for his landscapes, he seemed to find painting portraits his greatest ambition.[54] He said of portrait studies, "The only thing in painting that excites me to the depths of my soul, and which makes me feel the infinite more than anything else."[55]

To his sister he wrote, "I should like to paint portraits which appear after a century to people living then as apparitions. By which I mean that I do not endeavor to achieve this through photographic resemblance, but my means of our impassioned emotions – that is to say using our knowledge and our modern taste for color as a means of arriving at the expression and the intensification of the character."[54]

Of painting portraits, Van Gogh wrote: "in a picture I want to say something comforting as music is comforting. I want to paint men and women with that something of the eternal which the halo used to symbolize, and which we seek to communicate by the actual radiance and vibration of our coloring."[56]

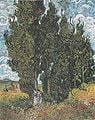

Cypresses

One of Van Gogh's most popular and widely known series are his Cypresses. During the Summer of 1889, at sister Wil's request, he made several smaller versions of Wheat Field with Cypresses.[57] These works are characterized by swirls and densely painted impasto, and produced one of his best-known paintings, The Starry Night. Other works from the series include Olive Trees with the Alpilles in the Background (1889) Cypresses (1889), Cypresses with Two Figures (1889–1890), Wheat Field with Cypresses (1889), (Van Gogh made several versions of this painting that year), Road with Cypress and Star (1890), and Starry Night Over the Rhone (1888). They have become synonymous with Van Gogh's work through their stylistic uniqueness. According to art historian Ronald Pickvance,

Road with Cypress and Star (1890), is compositionally as unreal and artificial as the Starry Night. Pickvance goes on to say the painting Road with Cypress and Star represents an exalted experience of reality, a conflation of North and South, what both Van Gogh and Gauguin referred to as an "abstraction." Referring to Olive Trees with the Alpilles in the Background, on or around 18 June 1889, in a letter to Theo, he wrote, "At last I have a landscape with olives and also a new study of a Starry Night."[58]

Cypresses, 1889, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Hoping to attain a gallery for his work, his undertook a series of paintings including Still Life: Vase with Twelve Sunflowers (1888), and Starry Night Over the Rhone (1888), all intended to form the décorations for the Yellow House.[59][60]

Flowering Orchards

The series of Flowering Orchards, sometimes referred to as the Orchards in Blossom paintings, were among the first groups of work that Van Gogh completed after his arrival in Arles, Provence in February 1888. The 14 paintings in this group are optimistic, joyous and visually expressive of the burgeoning Springtime. They are delicately sensitive, silent, quiet and unpopulated. About The Cherry Tree Vincent wrote to Theo on 21 April 1888 and said he had 10 orchards and: one big (painting) of a cherry tree, which I've spoiled.[61] The following spring he painted another smaller group of orchards, including View of Arles, Flowering Orchards.[45]

Van Gogh was taken by the landscape and vegetation of the South of France, and often visited the farm gardens near Arles. Because of the vivid light supplied by the Mediterranean climate his palette significantly brightened.[62] From his arrival, he was interested in capturing the effect of the seasons on the surrounding landscape and plant life.

Flowers

Van Gogh painted several versions of landscapes with flowers, including hisView of Arles with Irises, and paintings of flowers, including Irises, Sunflowers,[63] lilacs and roses. Some reflect his interests in the language of color, and also in Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints.[64]

He completed two series of sunflowers. The first dated from his 1887 stay in Paris, the second during his visit to Arles the following year. The Paris series shows living flowers in the ground, in the second, they are dying in vases. The 1888 paintings were created during a rare period of optimism for the artist. He intended them to decorate a bedroom where Gauguin was supposed to stay in Arles that August, when the two would create the community of artists Van Gogh had long hoped for. The flowers are rendered with thick brushstrokes (impasto) and heavy layers of paint.[65]

In an August 1888 letter to Theo, he wrote,

- "I am hard at it, painting with the enthusiasm of a Marseillais eating bouillabaisse, which won't surprise you when you know that what I'm at is the painting of some sunflowers. If I carry out this idea there will be a dozen panels. So the whole thing will be a symphony in blue and yellow. I am working at it every morning from sunrise on, for the flowers fade so quickly. I am now on the fourth picture of sunflowers. This fourth one is a bunch of 14 flowers ... it gives a singular effect."[65]

Wheat fields

Van Gogh made several painting excursions during visits to the landscape around Arles. He made a number of paintings featuring harvests, wheat fields and other rural landmarks of the area, including The Old Mill (1888); a good example of a picturesque structure bordering the wheat fields beyond.[66] It was one of seven canvases sent to Pont-Aven on 4 October 1888 as exchange of work with Paul Gauguin, Émile Bernard, Charles Laval, and others.[66] At various times in his life, Van Gogh painted the view from his window – at The Hague, Antwerp, Paris. These works culminated in The Wheat Field series, which depicted the view he could see from his adjoining cells in the asylum at Saint-Rémy.[67]

Writing in July 1890, Van Gogh said that he had become absorbed "in the immense plain against the hills, boundless as the sea, delicate yellow".[68] He had become captivated by the fields in May when the wheat was young and green. The weather worsened in July, and he wrote to Theo of "vast stretches of wheat under troubled skies," adding that he did not "need to go out of my way to try and express sadness and extreme loneliness."[69] In particular, the work Wheatfield with Crows serves as a compelling and poignant expression of the artist's state of mind in his final days, a painting Hulsker discusses as being associated with "melancholy and extreme loneliness," a painting with a "somber and threatening aspect," a "doom-filled painting with threatening skies and ill-omened crows."[70]

Legacy

Posthumous fame

Following his first exhibitions in the late 1880s, Van Gogh's fame grew steadily among colleagues, art critics, dealers and collectors.[71] After his death, memorial exhibitions were mounted in Brussels, Paris, The Hague and Antwerp. In the early 20th century, there were retrospectives in Paris (1901 and 1905), and Amsterdam (1905), and important group exhibitions in Cologne (1912), New York (1913) and Berlin (1914) These had a noticeable impact on later generations of artists.[72] By the mid twentieth century Van Gogh was seen as one of the greatest and most recognizable painters in history.[73] In 2007 a group of Dutch historians compiled the "Canon of Dutch History" to be taught in schools and included Van Gogh as one of the fifty topics of the canon, alongside other national icons such as Rembrandt and De Stijl.[74]

Together with those of Pablo Picasso, Van Gogh's works are among the world's most expensive paintings ever sold, as estimated from auctions and private sales. Those sold for over $100 million (today's equivalent) include Portrait of Dr. Gachet,[75] Portrait of Joseph Roulin,[76] and Irises.[77] A Wheatfield with Cypresses was sold in 1993 for $57 million, a spectacularly high price at the time,[78] while his Self Portrait with Bandaged Ear was sold privately in the late 1990s for an estimated $80/$90 million.[79]

Influence

In his final letter to Theo, Vincent admitted that as he did not have any children, he viewed his paintings as his progeny. Reflecting on this, the historian Simon Schama concluded that he "did have a child of course, Expressionism, and many, many heirs." Schama mentioned a wide number of artists who have adapted elements of Van Gogh's style, including Willem de Kooning, Howard Hodgkin and Jackson Pollock.[80] The Fauves extended both his use of color and freedom in application, as did German Expressionists of the Die Brücke group, and as other early modernists.[81] Abstract Expressionism of the 1940s and 1950s is seen as in part inspired from Van Gogh's broad, gestural brush strokes. In the words of art critic Sue Hubbard: "At the beginning of the twentieth century Van Gogh gave the Expressionists a new painterly language that enabled them to go beyond surface appearance and penetrate deeper essential truths. It is no coincidence that at this very moment Freud was also mining the depths of that essentially modern domain – the subconscious. This beautiful and intelligent exhibition places Van Gogh where he firmly belongs; as the trailblazer of modern art."[82]

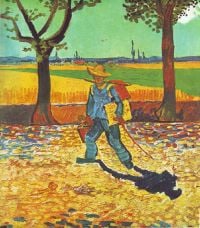

In 1957, Francis Bacon (1909–1992) based a series of paintings on reproductions of Van Gogh's The Painter on the Road to Tarascon, the original of which was destroyed during World War II. Bacon was inspired by not only an image he described as "haunting," but also Van Gogh himself, whom Bacon regarded as an alienated outsider, a position which resonated with Bacon. The Irish artist further identified with Van Gogh's theories of art and quoted lines written in a letter to Theo, "[R]eal painters do not paint things as they are...They paint them as they themselves feel them to be."[83]

Notes

- ↑ Van Gogh's Letters, Unabridged and annotated. 347 "Letter to Theo, from Nuenen, c. 18 December, 1883" webexhibits.org. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Theo's wife later remarked that this was the happiest year of Vincent's life, cited in Kenneth Wilkie, In Search of Van Gogh (New York: Prima Publishing, Random House. 1991), 34-36.

- ↑ Wilkie, 38-52.

- ↑ Philip Callow, Vincent Van Gogh: A Life (Chicago, IL: Ivan R. Dee, 1990), 54.

- ↑ Kathleen Powers Erickson, At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision Of Vincent Van Gogh (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2003), 23.

- ↑ Letters of Vincent van Gogh 129, "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Petit-Wasmes, April 1879," and Letter 132. Van Gogh lodged in Wasmes, at 22 rue de Wilson, with Jean-Baptiste Denis, a breeder or grower ('cultivateur', in the French original) according to Letter 553b. "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh Petit-Wasmes, April 1879." Retrieved June 27, 2019. In the recollections of his nephew Jean Richez, gathered by Wilkie (in the 1970s), 72-78, Denis and his wife Esther were running a bakery, and Richez admits that the only source of his knowledge is Aunt Esther.

- ↑ Wilkie, 75.

- ↑ Wilkie, 77.

- ↑ Callow, 72.

- ↑ there are different views as to this period; Jan Hulsker in Vincent and Theo van Gogh, a dual biography (Ann Arbor, MI: Fuller Publications, 1990, ISBN 0940537052) opts for a return to the Borinage and then back to Etten in this period; the catalog for the 2006 Budapest Van Gogh exhibition supports the line taken in this article.

- ↑ Letter 158. "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh Etten, 18 November 1881." Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ see Jan Hulsker's speech The Borinage Episode and the Misrepresentation of Vincent van Gogh, Van Gogh Symposium, 10-11 May 1990, referenced in Erickson, 67-68.

- ↑ Wilkie, 79.

- ↑ Erickson, 5.

- ↑ Letter 153. "Letter to Theo dated 3 November 1881." Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Letter 161. "Letter to Theo 23 November 1881." Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Letter 164. "Letter from Etten c. 21 December 1881," describing the visit in more detail. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Letter 193. "Letter from Vincent to Theo, The Hague, 14 May 1882." Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Letter 193. "Letter from Vincent to Theo, The Hague, 14 May 1882." Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Martin Gayford, The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Arles (Little, Brown and Company, 2006), 130–131.

- ↑ Letter 166 "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh The Hague, 29 December 1881." Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Callow, 123-124.

- ↑ Wilkie, 176. Forceps were used in the birth. Baby Willem was 3.42 kg and 53 cm at birth, suggesting conception occurred late August or early September 1881 … see Wilkie, 201. Vincent had visited The Hague briefly 23 – 26 August where he visited Anton Mauve and viewed the Panorama Mesdag

- ↑ Callow, 132.

- ↑ Letter 203. "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh The Hague, 30 May 1882" (postcard written in English). Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Letter from Municipal Hospital 206. "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh The Hague, 8 or 9 June 1882." Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Johannes de Looyer, Karel van England, Hendricus Dekkers, and Piet van Hoorn all as old men recalled being paid 5, 10 or 50 cents per nest, depending on the type of bird. See Wilkie, 25-26, and Theo's son's note. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Vincent's nephew noted some reminiscences of local residents in 1949, including the description of the speed of his drawing. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Wilkie, 82.

- ↑ Callow, 181.

- ↑ Callow, 184.

- ↑ D. Druick and P. Zegers, Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Studio of the South (London: Thames & Hudson, 2001), 81 ; Gayford, 50.

- ↑ Gayford, 16.

- ↑ Callow, 219.

- ↑ Gayford, 18.

- ↑ Alfred Nemeczek, Van Gogh in Arles (Prestel Verlag, 1999), 61.

- ↑ According to Drs. V. Doiteau & Leroy, the diagonal cut removed the lobe and probably a little more. V. Doiteau & E. Leroy. La Folie de Vincent van Gogh. (Paris: 1928. in French)

- ↑ Angelique Chrisafis, Art historians claim Van Gogh's ear 'cut off by Gauguin' The Guardian, May 4, 2009. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Callow, 246.

- ↑ Ingo F. Walther and Rainer Metzger, Van Gogh: the Complete Paintings (Berlin: Benedikt Taschen, 1990). One year before his death he painted Irises, one of his most beloved and beautiful paintings, which hangs in the Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

- ↑ Letter 648. "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh Auvers-sur-Oise, 10 July 1890." Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Sjraar Van Heugten, Van Gogh The Master Draughtsman (London: Thames and Hudson, 2005, ISBN 978-0500238257), 246–251.

- ↑ Artists working in Black & White, i.e., for illustrated papers like The Graphic or Illustrated London News were among Van Gogh's favorites. See Ronald Pickvance, English Influences on Vincent van Gogh (London: Arts Council, 1974).

- ↑ Roland Dorn and George S. Keyes, Van Gogh Face to Face: The Portraits (Thames & Hudson, 2000, ISBN 978-0895581532).

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Jan Hulsker, The Complete Van Gogh (1980), 385.

- ↑ Albert Boime, Vincent van Gogh: Die Sternennacht (Frankfurt: Fischer, 1989, ISBN 978-3596239535).

- ↑ At around 8:00 pm on June 16, 1890, as astronomers determined by Venus' position in the painting. "Star dates Van Gogh canvas." BBC News, March 8, 2001. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Ronald Pickvance, Van Gogh in Saint-Remy and Auvers (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986, ISBN 978-0870994777), 131.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Irish and World Art, art of self-portrait. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Self Portrait without Beard, 1889 by Vincent Van Gogh. VincentvanGogh.org. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Ben Cohen, A Tale of Two Ears. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. June 2003. vol. 96. issue 6. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Self Portraits. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Ingo F. Walther and Rainer Metzger, Van Gogh: the Complete Paintings (Berlin: Benedikt Taschen, 1997, ISBN 3822882658), 653.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Laurence Channing and Barbara J. Bradley, Monet to Dalí: Impressionist and Modern Masterworks from the Cleveland Museum of Art (Hudson Hills, 2007, ISBN 978-0940717909), 67.

- ↑ La Mousmé National Gallery of Art. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Portrait of Madame Augustine Roulin and Baby Marcelle. Collections. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Pickvance (1986), 132–133.

- ↑ Pickvance (1986), 101; 189–191

- ↑ Pickvance (1984), 175–176.

- ↑ Letter 595 Vincent to Theo, 17 or 18 June 1889. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Pickvance (1984), 45–53.

- ↑ Derek Fell, The Impressionist Garden (Frances Lincoln, 1997, ISBN 978-0711211483), 32.

- ↑ "Letter 573" Vincent to Theo. 22 or 23 January 1889. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Pickvance (1986), 80–81; 184–187.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 "Sunflowers 1888." National Gallery, London. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Pickvance (1984), 177.

- ↑ Hulsker (1980), 390–394.

- ↑ Cliff Edwards, Van Gogh and God: A Creative Spiritual Quest (Loyola University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0829406214), 115.

- ↑ Letter 649. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Hulsker (1990), 478-479.

- ↑ John Rewald, Studies in Post-Impressionism (Harry N. Abrams, 1986, ISBN 978-0810916326), 244–254.

- ↑ John Rewald, "The posthumous fate of Vincent van Gogh 1890–1970." Museumjournaal, August–September 1970. Republished in Rewald (1986), 248.

- ↑ "Vincent van Gogh The Dutch Master of Modern Art has his Greatest American Show," Life Magazine, October 10, 1949, 82–87. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ The Canon of the Netherlands Foundation entoen.nu. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Andrew Decker, "The Silent Boom", Artnet.com. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Portrait of Joseph Roulin, 1889 by Vincent Van Gogh VincentvanGogh.org. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Irises, 1889 by Vincent Van Gogh VincentvanGogh.org. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Most Valuable Paintings in Private Collections TheArtWolf.com. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ G. Fernández, The Most Expensive Paintings ever sold, TheArtWolf.com. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Simon Schama, Vincent Van Gogh Critical Reception Artable. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ David Minthorn, NYC exhibit highlights Van Gogh's impact on German modernists USA Today, 2007. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Sue Hubbard, "Vincent Van Gogh and Expressionism." Independent, 2007. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ↑ Dennis Farr, Michael Peppiatt, and Sally Yard, Francis Bacon: A Retrospective (Harry N Abrams, 1999, ISBN 978-0810929258), 112.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beaujean, Dieter. Vincent van Gogh: Life and Work. Könemann, 1999. ISBN 3829029381

- Boime, Albert. Vincent van Gogh: Die Sternennacht. Frankfurt: Fischer, 1989. ISBN 978-3596239535

- Callow, Philip. Vincent Van Gogh: A Life. Chicago, IL: Ivan R. Dee, 1990. ISBN 1566631343

- Channing, Laurence, and Barbara J. Bradley. Monet to Dalí: Impressionist and Modern Masterworks from the Cleveland Museum of Art. Hudson Hills, 2007. ISBN 978-0940717909

- Doiteau, V. Leroy, E. La Folie de Vincent van Gogh. Paris: 1928. (in French) Written by two doctors (psychiatrists.)

- Dorn, Roland, and George S. Keyes. Van Gogh Face to Face: The Portraits. Thames & Hudson, 2000. ISBN 978-0895581532

- Druick, Douglas W., and Peter Kort Zegers. Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Studio of the South. London: Thames & Hudson, 2001. ISBN 978-0500510544

- Erickson, Kathleen Powers. At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision of Vincent van Gogh. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2003. ISBN 0802849784

- Farr, Dennis, Michael Peppiatt, and Sally Yard. Francis Bacon: A Retrospective. Harry N Abrams, 1999. ISBN 978-0810929258

- Fell, Derek. The Impressionist Garden. Frances Lincoln, 1997. ISBN 978-0711211483

- Gayford, Martin. The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Arles. Little, Brown and Company, 2006. ISBN 0316769010

- Hulsker, Jan. The Complete Van Gogh. Outlet; 1980 Edition edition, 1986. ISBN 978-0810917019

- Hulsker, Jan. The Borinage Episode and the Misrepresentation of Vincent van Gogh, speech at Van Gogh Symposium, 10-11 May 1990, cited in Philip Callow. Vincent Van Gogh: A Life.

- Hulsker, Jan. Vincent and Theo van Gogh, a dual biography. Ann Arbor, MI: Fuller Publications, 1990. ISBN 0940537052

- Nemeczek, Alfred. Van Gogh in Arles. Prestel Verlag, 1999. ISBN 3791322303

- Pickvance, Ronald. English Influences on Vincent van Gogh. London: Arts Council, 1974. ASIN B002J094MY

- Pickvance, Ronald. Van Gogh in Arles. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984. ISBN 978-0870993756

- Pickvance, Ronald. Van Gogh in Saint-Remy and Auvers. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986. ISBN 978-0870994777

- Rewald, John. Studies in Post-Impressionism. Harry N. Abrams, 1986. ISBN 978-0810916326

- Van Heugten, Sjraar. Van Gogh The Master Draughtsman. London: Thames and Hudson, 2005. ISBN 978-0500238257

- Walther, Ingo F. and Rainer Metzger. Van Gogh: the Complete Paintings. Berlin: Benedikt Taschen , 1997. ISBN 3822882658

- Wilkie, Kenneth. In Search of Van Gogh. New York: Prima Publishing, Random House. 1991. ISBN 1559581018 (first published as The Van Gogh Assignment. 1978)

External links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

- Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- Vincent van Gogh National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., United States.

- Van Gogh's Letters, unabridged and annotated.

- Van Gogh painted perfect turbulence - mathematical analysis of Van Gogh's works reveals that the stormy patterns in many of his paintings are uncannily like real turbulence of fluids.

- Vincent and Theo Movie directed by Robert Altman.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.