Paul Signac

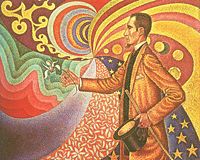

Paul Signac (November 11, 1863 - August 15, 1935) was a leading figure of French Neo-Impressionism, the school of painters that followed the Impressionists. Along with Georges-Pierre Seurat, he helped develop the pointillist style. Both Seurat and Signac were inspired by new scientific discoveries of the era that included a better understanding of color theory, optics and light.

The extraordinary quality and quantity of his artistic work, which included oils, watercolors, etchings, lithographs, and pen-and-ink pointillism, was matched by the breadth of his interests as a writer. Politically he considered himself an anarchist but toward the end of his life he deeply opposed fascism.

As president of the Société des Artistes Indépendants from 1908 until his death, Signac encouraged younger artists (he was the first to buy a painting by Henri Matisse) by exhibiting the controversial works of the Fauves and the Cubists.

Signac's comment that Seurat's works of pointillism were, "the most beautiful painter's drawings in existence,"[1] attests to the pride Neo-Impressionists found in their newly emerging style of art.

Early life

Paul Victor Jules Signac was born in Paris on November 11, 1863 into the family of a well-to-do master harness-maker. The family lived above the store they owned.

During the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) he was sent to northern France to live with his maternal grandmother and her second husband. By 1877 Signac was enrolled at the CollÚge Rollin in Montmartre (now the Lycée Jacques Decour); he remained a student there until 1880, the year his father died of tuberculosis. Soon after his father's death the family business was sold, thus releasing Signac from having to run it.

At age 16 Signac was thrown out of the fifth Impressionist exhibit by leading Post-Impresssionist Paul Gaugin for sketching a painting of Edgar Degas's that was on display.[2]The year 1880 proved to be a pivotal year for the young man who returned to the College Rollin in Montmarte to study mathematics and architecture, only to drop out after the first term to pursue painting.

Almost a year after leaving school Signac, along with several others, formed an informal literary society, which they named Les Harengs Saurs Ăpileptiques Baudelairiens et Anti-Philistins (The Epileptic, Baudelarian, Anti-philistine Smoked Herrings).

In 1882 he published two essays in the journal Le Chat Noir, and that summer he began his habit of escaping Paris for the countryside or the sea to paint; his first painting, Haystack (1883) was painted at his maternal grandmother's house at Guise. Here he became enamored with sailing and sailboats. During his lifetime he would own 32 sailing crafts in all.

In 1883 Signac began studying with painter Emile Jean Baptiste Philippe Bin (1825-1897), one of the founders of the Society of French Artists in 1881.

Friendships and exhibits

In 1884 he met Claude Monet and Georges-Pierre Seurat. At that time many of Signac's early works, including still lifes and landscapes, were influenced by the impressionism of artists such as Monet. Signac, struck by the systematic working methods of Seurat and by his theory of colors, became his faithful supporter.

Also in 1884 Signac, Seurat, Charles Angrand(1854-1926), and Henri Edmond Cross (1856-1910) formed the Société des Artistes Indépendants and from mid-December 1884, through January 17, 1885, the group held its first exhibition in Paris to benefit cholera victims.

In 1886 Camille Pissarro's friendship enabled Signac to get an invitation to exhibit in New York City at an exhibition titled Works in Oil and Pastel by the Impressionsts of Paris, although none of his six paintings sold. In the spring of 1886 Signac exhibited at the eighth and final Impressionist exhibition and on September 19, 1886, the term "néo-impressioniste" was used for the first time in a review by journalist Felix Fénéon of the second exhibition of the Independents.

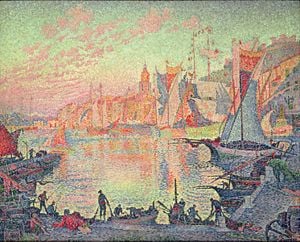

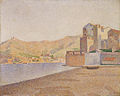

He left the capital each summer, to stay in the south of France in the village of Collioure or at St. Tropez, where he bought a house and invited his artistic colleagues. In 1887, he met Vincent van Gogh in Paris. Not only did they become friends, but they often painted together. Both artists were exhibiting their paintings along with Georges Seurat by the end of 1887.[3]

In late January 1888 Signac traveled to Brussels to exhibit at the Salon des XX. He also wrote a review of the exhibition using the pen name Neo that was published in Le Cri du People. By this time the exhibitions of the Société des Artistes Indépendants were well-established annual events thanks to Signac's efforts as an organizer.

When Seurat died suddenly in Paris in 1891 Signac was thrust into a primary position within the Neo-Impressionist movement, but Signac abandoned the technique in the early 20th century. Soon after Seurat's death Signac anonymously published an article titled Impressionistes et révolutionnaires in the literary supplement of La Révolte.

That summer he sailed in several regattas off the coast of Brittany, and in 1892 had seven paintings exhibited in the eighth exhibition held by the Neo-Impressionists. Later that year he exhibited his work in Antwerp and in December showed seven paintings in the first Neo-Impressionist exhibit.

He also made a short trip to Italy, visiting Genoa, Florence, and Naples.

Signac sailed a small boat to almost all the ports of France, to Holland, and around the Mediterranean Sea as far as Constantinople, basing his boat at St. Tropez, which was to ultimately become a favorite resort of modern artists.

In 1892 he married a distant cousin of Camille Pissarro's, Berthe Robles, who can be seen in his painting, The Red Stocking (1883). Witnesses at the wedding were artists Alexandre Lemonier, Maximilien Luce, Camille Pissarro and Georges Lecomte.

At the end of 1893 the Neo-Impressionist Boutique was opened in Paris and in 1894 Signac had an exhibition there of 40 of his watercolors. He exhibited widely in the late 1890s and early years of the twentieth century in Paris, Brussels, Provence, Berlin, Hamburg, the Hague, Venice, and elsewhere.

In the 1890s he became more involved with writing, working on a journal he had begun in 1894. In 1896 the anarchist journal Les Temps nouveaux published a black-and-white lithograph by Signac titled The Wreckers and in 1898 he signed a collective statement supporting Emile Zola's position in the infamous Dreyfus Affair and in 1906 placed an antimilitary drawing in Le Courier européen.

In 1896 Signac began working on his study of Eugene Delacroix and in mid-1899 published D'Eugéne Delacroix au néo-impressionnisme, excerpts of which had already appeared in French and German journals. In 1903 the German edition was published.

In November 1897, the Signacs moved to a new apartment in the "Castel BĂ©ranger," built by Hector Guimard. In December of the same year, they acquired a house in Saint-Tropez called "La Hune." There the painter had a vast studio constructed, which he inaugurated on August 16, 1898.

Last years

In 1909 Signac exhibited three pieces at the International Exhibition, better known as the Odessa Salon: Traghetto Lantern, Diablerets, and Port Decorated with Flags, Saint-Tropez. After Odessa the exhibition went to Kiev, Saint Petersburg, and Riga. Beginning in 1910 Signac slowed his output from the incredible pace he had maintained for more than 20 years. His sole painting that year was The Channel, Marseilles, and in 1911 he painted only Towers, Antibes. From there his output increased to nine paintings in 1912-1913, but he never again painted at his earlier, youthful pace.

In September 1913, Signac rented a house at Antibes, where he settled with his mistress, Jeanne Selmersheim-Desgrange, who gave birth to their daughter Ginette on October 2, 1913. Signac, who had left his wife Berthe but never divorced her, bequeathed his properties to her; the two remained friends for the rest of his life. On April 6, 1927, Signac adopted Ginette, his previously illegitimate daughter.

In early 1920 the Société des Artistes Indépendants renewed their annual exhibition (their 31st that year) though Signac was too ill to fully participate. He recovered sufficiently by spring to assume the post of commissioner of the French Pavillion at the Venice Biennale, where he mounted a special Cézanne exhibit. All 17 of Signac's works exhibited at the Biennale were sold within a month. Long acknowledged in the communities of artists and collectors, his fame was further cemented in 1922 when he was the subject of a monograph by Lucie Cousturier. In 1927 Signac published a monograph of his own devoted to the painter Johan Barthold Jongkind.

In late 1928 he accepted a commission to paint the ports of France in watercolors. He began with the eastern Mediterranean port of SĂšte in January 1929 and worked his way south, then west, and then northward. He continued working on the series until April 1931.

Politics

Politics and finances occupied Signac in the last years of his life, which coincided with the Great Depression. In December 1931 Signac met with Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948) in Paris. Despite his close friendship with Marcel Cachin, director of the French Communist Party daily newspaper, L'Humanité, Signac refused to join the party. He did, however, lend his support in 1932 to the Bureau of the World Committee Against War and often attended meetings of the Vigilance Committee of Anti-Fascist Intellectuals.

Although a self-avowed anarchist, like many of his contemporaries in France, including Camille Pissarro he was to become deeply opposed to Fascism towards the end of his life.[4] Signac equated anarchism - or social revolution - with artistic freedom. He once said, "The anarchist painter is not the one who will create anarchist pictures, but he who, without desire for recompense, will fight with all his individuality against official bourgeois conventions by means of a personal contribution."[5]

World War I had a profound and dispiriting affect on Signac who discontinued painting for three years. The annual exhibitions held by the Société des Artistes Indépendants were suspended, Signac himself rejecting a call to resume the exhibitions during wartime.

In December 1919 he entered into an agreement with three art dealers, turning over his artistic output to them at the rate of 21 oil paintings per year. The contract was renewed annually until 1928, when it was renegotiated.

On August 15, 1935, at the age of seventy-two, Paul Signac died from septicemia. His body was cremated and his ashes were buried at the PĂšre-Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

Technique

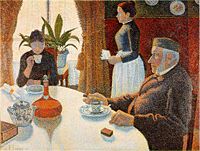

Seurat was working with an early stage of pointillism called Divisionism, which employed strokes not quite dot like. Under Seurat's influence Signac abandoned the short brushstrokes of impressionism in order to experiment with scientifically juxtaposed small dots of pure color, intended to combine and blend not on the canvas but in the viewer's eye - the defining feature of pointillism. The large canvas, Two Milliners, 1885, was the first example of Divisionist technique (also called Neo-impressionist or Pointillist) applied to an outdoor subject.

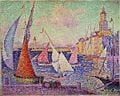

From his various ports of call, Signac brought back vibrant, colorful watercolors, sketched rapidly from nature. From these sketches, he would then paint large studio canvases that were carefully worked out in small, mosaic-like squares of color, quite different from the tiny, variegated dots previously used by Seurat.

Signac himself experimented with various media. As well as oil paintings and watercolors, he made etchings, lithographs, and many pen-and-ink sketches composed of the small, luminous dots.

The neo-impressionism of Signac inspired Henri Matisse and André Derain in particular, thus playing a decisive role in the evolution of Fauvism, a significant forerunner to Expressionism.

Watercolors form an important part of Signac's oeuvre and he produced a large quantity during his numerous visits to Collioure, Port-en-Bressin, La Rochelle, Marseille, Venice and Istanbul. The fluid medium allowed for greater expression than is found in his oil paintings, which are sometimes constrained by the limitations of color theory. Color being an important aspect of the artist's work, monochrome wash drawings such as ScÚne de marché are more rare.

Legacy

Signac wrote several important works on the theory of art, among them From Eugene Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism, published in 1899; a monograph devoted to Johan Barthold Jongkind (1819-1891), published in 1927; several introductions to the catalogs of art exhibitions; and many other unpublished writings. The quality and quantity of his work as an artist was matched by his efforts as a writer.

In 2007, Paul Signac's Cassis. Cap Canaille, from 1889 was sold in auction at Christie's for $14 million, setting a record for the artist.[6] Other works of his have sold for millions at similar auctions.

Gallery

Notes

- â Francine Prose. "Not the Seurat We Think We Know." Wall Street Journal [New York, NY] Nov. 29, 2007, Eastern edition: D.8. National Newspapers (5). ProQuest. <http://www.proquest.com.access-proxy.sno-isle.org/> Retrieved December 1, 2007.

- â Encyclopedia of World Biography Supplement, [1]Retrieved January 3, 2008.

- â Resource Center, galenet.galegroup.comRetrieved January 3, 2008.

- â John. Organise! 54 by the Anarchist Federation."People's history": Paul Signac a short biography of the artist, with information about his anarchist politics. Lib.com.org. Retrieved Dec. 3, 2007.

- â Ibid."People's history": Paul Signac. Retrieved Dec. 3, 2007.

- â BBC News online.Art collection is sold for $395m News.bbc.co.uk. (November 7, 2007) Retrieved December 5, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Encyclopedia of World Biography Supplement, Vol. 23. "Paul Signac." Gale Publishing, 2003. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale. 2007.

- Signac 1863-1935, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris 2001 ISBN 2711841278

- The New EncyclopĂŠdia Britannica, 1988, Volume 10, MicropĂŠdia, 796

- Prose, Francine. "Not the Seurat We Think We Know. " Wall Street Journal, New York, NY. (Nov. 29, 2007), Eastern edition: D.8. National Newspapers (5). ProQuest. Sno-Isle Libraries, Marysville, WA. 30 Nov. 2007.

Further Reading

- Bocquillon-Ferretti, Marina. 2001. Signac watercolors. Paris: Vilo. ISBN 2845760272

- Cachin, Françoise. 1971. Paul Signac. Greenwich, Conn: New York Graphic Society. ISBN 0821204823

- Ratliff, Floyd, and Paul Signac. 1992. Paul Signac and Color in Neo-Impressionism. New York: Rockefeller University Press. ISBN 0874700507

- Signac, Paul, and Charles Cachin. 1990. Paul Signac Watercolors, St. Louis, Mo: Greenberg Gallery. ISBN 0942779061

External links

All links retrieved November 22, 2022.

- Paul Signac Paul-signac.com.

- Paul Signac Ibiblio.org.

- Paul Signac Artcyclopedia.com.

- Paul Signac, a biography of the artist, with information about his anarchist politics

- Paul Signac biography Abcgallery.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.