Museum of Modern Art

| Established | November 7, 1929 |

|---|---|

| Location | 11 West 53rd Street, Manhattan, New York, USA |

| Visitor figures | 2.5 million/yeara |

| Director | Glenn D. Lowry |

| Website | www.moma.org |

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is an art museum located in Midtown Manhattan in New York City, USA, on 53rd Street, between Fifth and Sixth Avenues. It has been singularly important in developing and collecting modernist art, and is often identified as the most influential museum of modern art in the world.[1] The museum's collection offers an unparalleled overview of modern and contemporary art,[2] including works of architecture and design, drawings, painting, sculpture, photography, prints, illustrated books, film, and electronic media.

MoMA's library and archives hold over 300,000 books, artist books, and periodicals, as well as individual files on more than 70,000 artists. The archives contain primary source material related to the history of modern and contemporary art.

History

The idea for the Museum of Modern Art was developed in 1928 primarily by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller (wife of John D. Rockefeller Jr.) and two of her friends, Lillie P. Bliss and Mrs. Cornelius J. Sullivan.[3] They became known variously as "the Ladies", "the daring ladies" and "the adamantine ladies". They rented modest quarters for the new museum and it opened to the public on November 7, 1929, nine days after the Wall Street Crash. Abby had invited A. Conger Goodyear, the former president of the board of trustees of the Albright Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York, to become president of the new museum. Abby became treasurer. At the time, it was America's premier museum devoted exclusively to modern art, and the first of its kind in Manhattan to exhibit European modernism.[4]

Goodyear enlisted Paul J. Sachs and Frank Crowninshield to join him as founding trustees. Sachs, the associate director and curator of prints and drawings at the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, was referred to in those days as a collector of curators. Goodyear asked him to recommend a director and Sachs suggested Alfred H. Barr Jr., a promising young protégé. Under Barr's guidance, the museum's holdings quickly expanded from an initial gift of eight prints and one drawing. Its first successful loan exhibition was in November 1929, displaying paintings by Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cezanne, and Seurat.[5]

First housed in six rooms of galleries and offices on the twelfth floor of Manhattan's Heckscher Building,[6] on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 57th Street, the museum moved into three more temporary locations within the next ten years. Abby's husband was adamantly opposed to the museum (as well as to modern art itself) and refused to release funds for the venture, which had to be obtained from other sources and resulted in the frequent shifts of location. Nevertheless, he eventually donated the land for the current site of the Museum, plus other gifts over time, and thus became in effect one of its greatest benefactors.[7]

During that time it initiated many more exhibitions of noted artists, such as the lone Vincent van Gogh exhibition on November 4, 1935. Containing an unprecedented sixty-six oils and fifty drawings from the Netherlands, and poignant excerpts from the artist's letters, it was a major public success and became "a precursor to the hold van Gogh has to this day on the contemporary imagination."[8]

The museum also gained international prominence with the hugely successful and now famous Picasso retrospective of 1939-40, held in conjunction with the Art Institute of Chicago. In its range of presented works, it represented a significant reinterpretation of Picasso for future art scholars and historians. This was wholly masterminded by Barr, a Picasso enthusiast, and the exhibition lionized Picasso as the greatest artist of the time, setting the model for all the museum's retrospectives that were to follow.[9]

When Abby Rockefeller's son Nelson was selected by the board of trustees to become its flamboyant president in 1939, at the age of thirty, he became the prime instigator and funder of its publicity, acquisitions and subsequent expansion into new headquarters on 53rd Street. His brother, David Rockefeller, also joined the Museum's board of trustees, in 1948, and took over the presidency when Nelson took up position as Governor of New York in 1958.

David subsequently employed the noted architect Philip Johnson to redesign the Museum garden and named it in honor of his mother, the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden. He and the Rockefeller family in general have retained a close association with the Museum throughout its history, with the Rockefeller Brothers Fund funding the institution since 1947. Both David Rockefeller, Jr. and Sharon Percy Rockefeller (wife of Senator Jay Rockefeller) currently sit on the board of trustees.

In 1937, MoMA had shifted to offices and basement galleries in the Time & Life Building in Rockefeller Center. Its permanent and current home, now renovated, designed in the International Style by the modernist architects Philip Goodwin and Edward Durell Stone, opened to the public on May 10, 1939, attended by an illustrious company of 6,000 people, and with an opening address via radio from the White House by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[10]

Artworks

Considered by many to have the best collection of modern Western masterpieces in the world, MoMA's holdings include more than 150,000 individual pieces in addition to approximately 22,000 films and four million film stills. The collection houses such important and familiar works as the following:

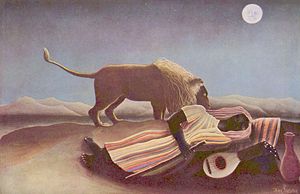

- The Sleeping Gypsy by Henri Rousseau

- The Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh

- Les Demoiselles d'Avignon by Pablo Picasso

- The Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dalí

- Broadway Boogie Woogie by Piet Mondrian

- Campbell's Soup Cans by Andy Warhol

- The Seed of the Areoi by Paul Gauguin

- Water Lilies triptych by Claude Monet

- The Dance (painting) by Henri Matisse

- The Bather by Paul Cézanne

- The City Rises by Umberto Boccioni

- "Love Song (Giorgio de Chirico)" by Giorgio De Chirico

- "One: Number 31, 1950" by Jackson Pollock

- Christina's World by Andrew Wyeth

- Self-Portrait With Cropped Hair by Frida Kahlo

- Painting (1946) by Francis Bacon

It also holds works by a wide range of influential American artists including Cindy Sherman, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jasper Johns, Edward Hopper, Chuck Close, Georgia O'Keefe, and Ralph Bakshi.

MoMA developed a world-renowned art photography collection, first under Edward Steichen and then John Szarkowski, as well as an important film collection under the Museum of Modern Art Department of Film and Video. The film collection owns prints of many familiar feature-length movies, including Citizen Kane and Vertigo, but the department's holdings also contains many less-traditional pieces, including Andy Warhol's eight-hour Empire and Chris Cunningham's music video for Björk's All Is Full of Love. MoMA also has an important design collection, which includes works from such legendary designers as Paul László, the Eameses, Isamu Noguchi, and George Nelson. The design collection also contains many industrial and manufactured pieces, ranging from a self-aligning ball bearing to an entire Bell 47D1 helicopter.

Exhibition houses

At various points in its history, MoMA has sponsored and hosted temporary exhibition houses, which have reflected seminal ideas in architectural history.

- 1949: exhibition house by Marcel Breuer

- 1950: exhibition house by Gregory Ain[11]

- 1955: Japanese exhibition house

- 2008: Prefabricated houses planned[12][13] by:

- Kieran Timberlake Architects

- Lawrence Sass

- Jeremy Edmiston and Douglas Gauthier

- Leo Kaufmann Architects

- Richard Horden

Renovation

MoMA's midtown location underwent extensive renovations in the 2000s, closing on May 21, 2002, and reopening to the public in a building redesigned by the Japanese architect Yoshio Taniguchi, on November 20, 2004. From June 29, 2002 until September 27, 2004, a portion of its collection was on display in what was dubbed MoMA QNS, a former Swingline staple factory in the Long Island City section of Queens.

The renovation project nearly doubled the space for MoMA's exhibitions and programs and features 630,000 square feet of new and redesigned space. The Peggy and David Rockefeller Building on the western portion of the site houses the main exhibition galleries, and The Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman Education and Research Building on the eastern portion provides over five times more space for classrooms, auditoriums, teacher training workshops, and the Museum's expanded Library and Archives. These two buildings frame the enlarged Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden, home to two works by Richard Serra.

MoMA's reopening brought controversy as its admission cost increased from US$12 to US$20, making it one of the most expensive museums in the city; however it has free entry on Fridays after 4pm, thanks to sponsorship from Target Stores. The architecture of the renovation is controversial. At its opening, some critics thought that Taniguchi's design was a fine example of contemporary architecture, while many others were extremely displeased with certain aspects of the design, such as the flow of the space.[14][15][16]

MoMA has seen its average number of visitors rise to 2.5 million from about 1.5 million a year before its new granite and glass renovation. The museum's director, Glenn D. Lowry, expects average visitor numbers eventually to settle in at around 2.1 million.[17]

See also

- Art museum

- Nelson Rockefeller

- David Rockefeller

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Helen Gardner, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya, Gardner's Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective (Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2006). ‚ÄúThe Museum of Modern Art in New York City is consistently identified as the institution most responsible for developing modernist art...the most influential museum of modern art in the world.‚ÄĚ (p. 795)

- ‚ÜĎ Museum of Modern Art - New York Art World Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Wendy Jeffers, "Abby Aldrich Rockefeller: patron of the modern", Magazine Antiques, 2004-10. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ First modern art museum featuring European works in Manhattan. Michael FitzGerald, Making Modernism: Picasso and the Creation of the Market for Twentieth-Century Art (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995), 120.

- ‚ÜĎ Origins of MoMA and first successful loan exhibition. See John Ensor Harr and Peter J. Johnson, The Rockefeller Century: Three Generations of America's Greatest Family (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1988), 217-18.

- ‚ÜĎ Carter B. Horsley, The Crown Building (formerly the Heckscher Building) The City Review. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ John D. Rockefeller, Jr. one of MoMA's greatest benefactors. See Bernice Kert, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller: The Woman in the Family (New York: Random House, 1993), 376-386.

- ‚ÜĎ Precursor to the current hold of van Gogh in public imagination. Bernice Kert, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller: The Woman in the Family (New York: Random House, 1993), 376.

- ‚ÜĎ MoMA's international prominence through the Picasso retrospective of 1939-40. See FitzGerald, op.cit., pp.243-62.

- ‚ÜĎ The formal opening of MoMA, Time Magazine. Monday, May. 22, 1939. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Anthony Denzer, Gregory Ain: The Modern Home As Social Commentary (New York: Rizzoli, 2008).

- ‚ÜĎ MoMA Announces Selection of Five Architects to Display Prefabricated Homes Outside Museum in Summer 2008 Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Robin Pogrebin, "Is Prefab Fab? MoMA Plans a Show", New York Times, January 8, 2008. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ John Updike, Invisible Cathedral, The New Yorker, 2004-11-15. ‚ÄúNothing in the new building is obtrusive, nothing is cheap. It feels breathless with unspared expense. It has the enchantment of a bank after hours, of a honeycomb emptied of honey and flooded with a soft glow.‚ÄĚ Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Roberta Smith, Tate Modern's Rightness Versus MoMA's Wrongs, New York Times, 2006-11-01. ‚ÄúThe museum‚Äôs big, bleak, irrevocably formal lobby atrium ... is space that the Modern could ill afford to waste, and such frivolousness continues in its visitor amenities: the hard-to-find escalators and elevators, the too-narrow glass-sided bridges, the two-star restaurant on prime garden real estate where there should be an affordable cafeteria ...Yoshio Taniguchi‚Äôs MoMA is a beautiful building that plainly doesn‚Äôt work.‚ÄĚ Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Witold Rybczynski, Street Cred: Another Way of Looking at the New MOMA, Slate.com, 2005-03-30. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ "Build Your Dream, Hold Your Breath", The New York Times, August 6, 2006. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Denzer, Anthony. Gregory Ain: The Modern Home As Social Commentary. New York: Rizzoli, 2008. ISBN 9780847830626

- FitzGerald, Michael C. Making Modernism: Picasso and the Creation of the Market for Twentieth Century Art. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995. ISBN 9780374106119

- Gardner, Helen, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya. Gardner's Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2006. ISBN 0495004782

- Harr, John Ensor, and Peter J. Johnson. The Rockefeller Century. New York: Scribner, 1988. ISBN 9780684189369

- Jeffers, Wendy. "Abby Aldrich Rockefeller: patron of the modern", Magazine Antiques, 2004-10. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- Kert, Bernice. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller: The Woman in the Family. New York: Random House, 1993.

- Lynes, Russell, Good Old Modern: An Intimate Portrait of the Museum of Modern Art. New York: Athenaeum, 1973.

- Reich, Cary. The Life of Nelson A. Rockefeller: Worlds to Conquer 1908-1958. New York: Doubleday, 1996.

External links

All links retrieved June 2, 2025.

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.