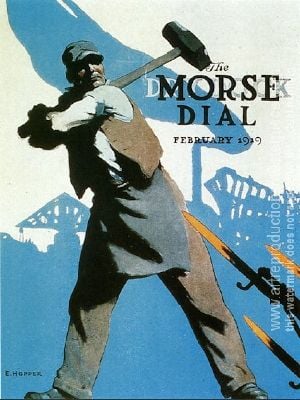

Edward Hopper

Edward Hopper (July 22, 1882 – May 15, 1967) was one of the foremost realists among twentieth century American artists. Although he supported himself initially through illustration he was also known for his etchings. He is best remembered for his vision of contemporary urban life and its accompanying loneliness and alienation. His work has been noted for its dramatic use of light and color and for infusing his subject matter with an eerie sense of isolation that borders on foreboding - thus the term Hopperesque.

After he began spending summers in Gloucester, Massachusets his art focused on watercolors of sailboats, lighthouses, seascapes and American Victorian architecture. The Mansard Roof painting that he did his first summer there was his breakthrough piece that brought him to public attention at the age of 40.

Later his signature works would become more urban in subject. His paintings of buildings and humans in relationship to those buildings created the feeling of a loss of humanness in the urban architecture that was replacing the rural more home-like structures. As such his art was a chronicling of his sense of the deterioration of the interior lives of Americans as the culture changed from rural to urban.

Early life and influences

Edward Hopper was born in Nyack, New York to prosperous dry-goods merchant, Garrett Henry Hopper. His mother Elizabeth Smith Hopper introduced her children to art and the theater at an early age. He began to draw at age seven after receiving a blackboard as a gift. By the age of twelve he was six feet tall, shy and withdrawn. [1]

His parents encouraged him to study commercial art so that he could earn a living. After high school, he began to commute to the New York School of Art to study illustration and painting. Two of his teachers, renowned in their day, were the artists Robert Henri and William Merritt Chase. Henri motivated his students to render realistic depictions of urban life and many went on to become important artists themselves, such as George Bellows and Rockwell Kent. This group of artists would become known as the Ashcan School of American art.

Between 1906 and 1910 Hopper lived in Paris where he fell under the influence of the Impressionists, especially their use of vibrant colors and dappled light. Unlike many of his contemporaries who imitated the abstract cubist experiments, the idealism of the realist painters resonated with Hopper, and his early projects reflect this influence. He sold his first painting in 1913, The Sailboat, which he painted after spending summers off of the coast of Maine and Massachusetts.

While he worked for several years as a commercial artist, Hopper continued painting. In 1925 he produced House by the Railroad, a classic work that marks his artistic maturity. The piece is the first of a series of stark urban and rural scenes that uses sharp lines and large shapes, played upon by unusual lighting to capture the lonely mood of his subjects. He derived his subject matter from the common features of American life — gas stations, motels, the railroad, or an empty street.

Later life and career

In 1923, while vacationing off of the coast of Massachussetts, Hopper, encouraged by fellow artist Josephine Nivinson, began to paint watercolors of local scenes. After she encouraged the Brooklyn Museum to display his works along with hers, Hopper garnered rave reviews and sold them his second painting in ten years, Mansard Roof.

The following summer the couple were married. They drew inspiration for their work by traveling throughout the United States with her often posing as the female figure for his paintings.

His work gained wider recognition when the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) gave him a solo show in 1933. He quickly became known for his rendering of Americana; its uniqueness and its mood in contrast to the European painters who painted America from their own perspective. One critic from this era described Hopper as "a true and powerful interpreter of the American scene."[2]

Hopper continued to paint in his old age, dividing his time between New York City and Truro, Massachusetts. He died in 1967, in his studio near Washington Square, in New York City.

Style and themes

Initially Hopper experimented with a variety of styles including traditional drawings and realistic self-portraits. Realism in the arts was becoming in vogue and was seen as a means of shifting focus away from idealized subjects, such as mythology, and on to more socially relevant themes.

The best known of Hopper's paintings, Nighthawks (1942), shows customers sitting at the counter of an all-night diner. The diner's harsh electric light sets it apart from the gentle night outside. The diners, seated at stools around the counter, appear isolated. The mood in Hopper's pictures often depict waiting or tedium. Although some pictures have almost a foreboding quality, they are not necessarily negative; they can also suggest possibility - the source of the mood is left to the viewer's imagination.[3]

Hopper's rural New England scenes, such as Gas (1940), are no less meaningful. In terms of subject matter, he has been compared to his contemporary, Norman Rockwell, but while Rockwell exulted in the rich imagery of small-town America, Hopper's work conveys the same sense of forlorn solitude that permeates his portrayal of city life. In Gas, Hopper exploits vast empty spaces, represented by a lonely gas station astride an empty country road. The natural light of the sky and the lush forest, are in sharp contrast to the glaring artificial light coming from inside the gas station.

It was Hopper's unique ability to convey a melancholic undertone in his paintings. His signature style became known for its deserted locales that were overshadowed by some form of loss, conveyed by the sheer tension of their emptiness.

Legacy

Amidst the rise of Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art and the accompanying profusion of styles, Hopper remained true to his vision. He once said, "The only quality that endures in art is a personal vision of the world. Methods are transient: personality is enduring." [4] Hopper's influence has reached many aspects of the arts including writing, filmmaking, dance, theater and even advertising.

His wife, who died 10 months after him, bequeathed his work to the Whitney Museum of American Art. Other significant paintings by Hopper are at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, The Des Moines Art Center, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Exhibitions

In 1961 First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy chose House of Squam Light to hang in the White House.

In 2004, a large selection of Hopper's paintings toured through Europe, visiting Cologne, Germany and Tate Modern in London. The Tate exhibition became the second most popular in the gallery's history, with 420,000 visitors in the three months it was open.

In 2007, an exhibition focusing on the period of Hopper’s greatest achievements—from about 1925 to mid-century—was under way at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The exhibit, comprising 50 oil paintings, 30 watercolors, and 12 prints, included favorites such as: Nighthawks, Chop Suey, and Lighthouse and Buildings, Portland Head, and Cape Elizabeth, Maine. The exhibition was organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., and The Art Institute of Chicago.

In popular culture

Hopper's influence on popular culture is undeniable. Homages to Nighthawks featuring cartoon characters or famous pop culture icons such as James Dean and Marilyn Monroe are often found in poster stores and gift shops. German film director Wim Wenders's 1997 film The End of Violence incorporates a tableau vivant of Nighthawks, recreated by actors.

His cinematic wide compositions and dramatic use of lights and darks has also made him a favorite among filmmakers. For example, House by the Railroad is said to have heavily influenced the iconic house in the Alfred Hitchcock film Psycho. The same painting has also been cited as being an influence on the home in the Terrence Malick film Days of Heaven.

To establish the lighting of scenes in the 2002 film Road to Perdition, director Sam Mendes drew from the paintings of Hopper as a source of inspiration, particularly for New York Movie.[5]

In 2004 British guitarist John Squire (formerly of The Stone Roses fame) released a concept album based on Hopper's work entitled Marshall's House. Each song on the album was inspired by and shares a title with a painting by Hopper.

Polish composer Paweł Szymański's Compartment 2, Car 7 for violin, viola, cello and vibraphone (2003) was inspired by Hopper's Compartment C, Car 293. [6]

The cable television channel Turner Classic Movies sometimes runs a series of animated clips based on Hopper paintings before they air their films.

Each of the 12 chapters in New Zealander Chris Bell (author)'s 2004 novel Liquidambar UKA Press/PABD) interprets one of Hopper's paintings to create a surreal detective story.

Hopper's artwork was used as the basis for the surface world in Texhnolyze, the Japanese animated dark cyberpunk thriller.

Selected works

- Night Shadows (1921) (etching) [2]

- The New York Restaurant (c. 1922) [3]

- House by the Railroad (1925) [4]

- Automat (1927)

- Night Windows (1928) [5]

- Chop Suey (1929)

- Early Sunday Morning (1930) [6]

- Room in New York (1932) [7]

- The Long Leg (1935) [8]

- House at Dusk (1935) [9]

- Compartment C, Car 293 (1938) [10]

- New York Movie (1939) [11]

- Ground Swell (1939)

- Gas (1940) [12]

- Office at Night (1940) [13]

- Nighthawks (1942)

- Rooms for Tourists (1945) [14]

- Rooms by the Sea (1951) [15]

- Morning Sun (1952) [16]

- Office in a Small City (1953)

- Excursion into Philosophy (1959) [17]

- People in the Sun (1960) [18]

- Sun in an Empty Room (1963) [19]

- Chair Car (1965) [20]

- The Lighthouse At Two Lights (1929) [21]

Notes

- ↑ "Edward Hopper," American Decades. Gale Research, 1998. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale, 2007.

- ↑ "Edward Hopper," American Decades. Gale Research, 1998. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale 2007.

- ↑ "Edward Hopper," American Decades. Gale Research, 1998. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale 2007.

- ↑ "Edward Hopper," American Decades. Gale Research, 1998. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale 2007

- ↑ Ray Zone. [1] "A Master of Mood." American Cinematographer accessdate 2007-06-06

- ↑ EMI Music Poland Emimusic.pl. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Berkow, Ita G., and Edward Hopper. Edward Hopper: An American Master. New York, NY: Smithmark, 1996. ISBN 0831780878

- Berman, Avis. "Hopper," Smithsonian Magazine. July 2007, 57.

- Cook, Greg."Visions of Isolation: Edward Hopper at the MFA", Boston Phoenix, May 4, 2007, 22, Arts and Entertainment. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- "Edward Hopper." American Decades. Gale Research, 1998. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, MI: Thomson Gale, 2007.

- "Edward Hopper." International Dictionary of Art and Artists. St. James Press, 1990. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center, Farmington Hills, MI: Thomson Gale, 2007.

- Levin, Gail. Edward Hopper: an intimate biography. New York: Knopf, 1995. ISBN 0394546644

- Lyons, Deborah, Edward Hopper, Adam D. Weinberg, and Julie Grau. Edward Hopper and the American Imagination. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art in association with W.W. Norton, 1995. ISBN 0393038149

- Lyons, Deborah, and Edward Hopper. Edward Hopper: Summer at the Seashore. Adventures in art. Munich: Prestel, 2002. ISBN 3791327372

- Mecklenburg, Virginia M., Edward Hopper, and Margaret Lynne Ausfeld. Edward Hopper: the watercolors. New York: W. W. Norton, 1999. ISBN 0393048497

- Rewald, John. The John Hay Whitney Collection. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1983. ISBN 0894680668

- Theisen, Gordon, and Edward Hopper. Staying Up Much Too Late: Edward Hopper's Nighthawks and the Dark Side of the American Psyche. New York: T. Dunne Books, 2006. ISBN 0312333420

External links

All links retrieved February 12, 2024.

- Graffeo, Christopher, ArtsEditor.com, 2007; "Alone, Together: examining the work of Edward Hopper", ArtsEditor.

- Pioch, Nicolas, WebMuseum, 2002; "Hopper, Edward", ibiblio.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.