Norman Rockwell

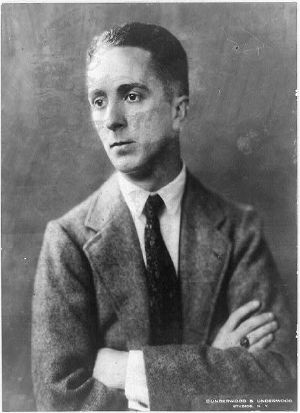

Norman Percevel Rockwell (February 3, 1894 â November 8, 1978) was one of the most famous and admired American illustrators and painters of the twentieth century. His works enjoy a broad popular appeal and he is most remembered for his Saturday Evening Post magazine covers that he illustrated for more than four decades.

His prodigious career, without necessarily intending to, chronicled American history from World War I through space exploration. And although most of his themes were about everyday people performing everyday minutia, from saying grace to playing baseball, later works reflected the social consciousness of the 1960s.

He was sometimes criticized for painting pictures overly saccharine and idealized. However, Rockwell was noted for being visually accurate in his masterfully detailed portraits. He once commented unpretentiously about the purpose of his art, âWithout thinking too much about it in specific terms, I was showing the America I knew and observed to others who might not have noticed. My fundamental purpose is to interpret the typical American. I am a story teller.â

Biography

Childhood

Norman Rockwell was born on February 3, 1894, in New York City to Jarvis Waring and Ann Mary (Hill) Rockwell. He had one sibling, a brother, Jarvis. Rockwellâs family lived in an apartment on the Upper West Side. His father, proud of their English heritage, used to read Charles Dickens to Norman and his brother on Sundays. Rockwell would sit and sketch pictures of the various, colorful characters from books like Oliver Twist. Both his view of the world and his powers of observation were greatly affected by the stories of Dickens. His family would spend summers away from the city, a welcomed respite for young Rockwell. Throughout most of his life he eschewed cityscapes while pastoral and country themes were to be a continuing motif in his paintings.

Rockwell attended Chase Art School at the age of 16. He then went on to the National Academy of Design, and finally transferred, to the Art Students League, where he was taught by Thomas Fogarty and George Bridgman. Both instructors instilled in their student a meticulous eye for detail and authenticity. Fogartyâs favorite admonition was that an illustration must be âan authorâs words in paint.â Their tutelage developed in Rockwell a fascination with accurate anatomy and facial expressions, two hallmarks of his illustrations.

His first job and real breakthrough came in 1912, at age 18. While still an art student, he began illustrating C.H. Claudy's "Tell Me Why Stories.â These early illustrations were all done in black and white. During this time, he also did illustrations for St. Nicholas Magazine and the Boy Scouts of America (BSA), an organization that he would hold a long association with. As a young illustrator, he was an admirer of the (chiefly) children's illustrator, Howard Pyle, who Rockwell called a "historian with a brush." His ambition, however, was to progress from the world of children's illustrations to more challenging and adult material and themes. At age 19 he became the art editor for Boys' Life, a post he held for several years. His first published magazine cover, Scout at Ship's Wheel, appeared on the Boys' Life September 1913 edition.

Early Career

During World War I, Rockwell attempted to enlist in the U.S. Navy, but was refused entry because at 6 feet (1.83 m) tall and 140 pounds (64 kg), he was eight pounds underweight. So, on a doctorâs suggestion and a friend's dare, he spent one night gorging himself on bananas, liquids, and donuts, and weighed enough to enlist the next day. He was given the role of a military artist and proceeded to paint pictures of soldiers, which he did with the intent of bolstering morale.

He reflected in his autobiography that it was often challenging to come up with ideas for pictures that everyone would like while the world was at war. His picture of a soldier returning from war after World War II (Homecoming G. I., Post cover, 1945) was displayed in various places all over the nation. Rockwell did not explicitly paint war scenes; rather he chose to capture and immortalize the tender moments, the small scenes, such as the returning G.I. being greeted at the fire escape by family, friends, and neighbors. Soldiers, sailors, and military civilians were to be one of Rockwellâs recurring themes.

Saturday Evening Post

Rockwell moved to New Rochelle, New York at age 21 and shared a studio with the cartoonist Clyde Forsythe, who worked for the Saturday Evening Post. With Forsythe's help, he submitted his first successful cover painting to the Post in 1916, Boy with Baby Carriage. He followed that success with Circus Barker and Strongman (published on June 3), Gramps at the Plate (August 5), Redhead Loves Hatty Perkins (September 16), and Man Playing Santa (December 9). Rockwell went on to publish a remarkable 321 covers for the Saturday Evening Post over the next 47 years.

Rockwell's success on the cover of the Post led to covers for other magazines of the day, most notably the Literary Digest, the Country Gentleman, Leslie's, Judge, People's Popular Monthly, and Life magazine.

Rockwell married his first wife, Irene O'Connor, in 1916. Irene was Rockwell's model in Mother Tucking Children into Bed, published on the cover of the Literary Digest on January 19, 1921. Although the couple was a part of the social milieu of New Rochelle, they were never really happy together. After 14 years of marriage and no children, they went their separate ways. Rockwell remarried the same year he divorced to schoolteacher Mary Barstow, with whom he had three children: Jarvis, Thomas, and Peter. Although Rockwell worked seven days a week and long hours, Mary shared in Rockwell's passion for his art. She attended to administrative details as well as provided keen observations and critiques as Rockwell could be a meticulous perfectionist.

In 1939, the Rockwell family moved to Arlington, Vermont, which provided him with the inspiration to paint the scenes of American small town life that he was to become so well known for. It was in Arlington where he painted Shuffleton's Barber Shop, considered by many critics to be one of his masterpieces. This was a technologically challenging piece because of the way the lighted back room of the barbershop is seen from the darkened and closed front room. The painting, in the way it captures light, demonstrates Rockwell's admiration for Dutch masters, like Vermeer and Rembrandt.

World War II and the Four Freedoms Series

In 1943, during World War II, Rockwell, too old to enlist, decided to contribute to the war effort by drawing âposters.â Initially rejected by the U.S. government, Post editor Ben Hibbon encouraged him to paint his idea of the Four Freedoms, but not just as covers. Rockwell received inspiration for the series from Franklin D. Rooseveltâs speech, which had declared that there were four principles for universal rights: âFreedom from Want, Freedom of Speech, Freedom to Worship, and Freedom from Fear.â How to translate the lofty ideals of Roosevelt's speech into specific art was Rockwellâs initial challenge. He received the idea for the first painting, Freedom of Speech when he observed one of his neighbors stand up to speak at a town hall meeting in Vermont. This was, ultimately, to be his favorite painting. Rockwell subsequently used other Vermont neighbors as models for the Four Freedoms series.

He wrestled with the project which took him seven months to complete and during which time he lost 15 pounds. However, the end result was that the pictures were reproduced and requested around the world. Freedom to Worship shows a diverse gathering praying in different forms under the heading, âEach according to the dictates of his own conscience.â Freedom From Fear shows two parents tucking their children safely into bed at night, and Freedom from Want is a painting of a Thanksgiving dinner. It was his own Thanksgiving dinner and Rockwell joked it was one of the only times he ate the model when he was finished painting it.

The paintings were published in 1943 by the Saturday Evening Post. The U.S. Treasury Department later promoted war bonds by exhibiting the originals in 16 cities. Although Rockwell is sometimes criticized for not producing "real" art, Post editor Ben Hibbon said of the paintings "to me they are the greatest human documents in the form of paint and canvas." That same year a fire in his studio destroyed numerous original paintings, costumes, and props.

In 1951, Rockwell painted what is considered his most popular painting, Saying Grace, which shows a grandmother and grandson saying grace in a railroad terminal. Rockwell's son, Jarvis, posed as the young man sitting at the table observing them. In accordance with Rockwell's standard, every detail was meticulously planned and had to be authentic from the knitting bag resting on the floor to the rainy and dreary window of the terminal.

Later, in 1959, his wife Mary died unexpectedly of heart failure, which resulted in Rockwell taking time off to grieve. It was during this break that he and his son Thomas produced his autobiography, My Adventures as an Illustrator, which was published in 1960. The Post printed excerpts from this book in eight consecutive issues, the first containing Rockwell's famous Triple Self-Portrait.

Look Magazine and Social Issues

Rockwellâs ability to deliver a message, and his flair for painstaking detail made him a favorite of the advertising industry. He was also commissioned to illustrate over 40 books including the ever-popular Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. His annual contributions for the Boy Scouts' calendars (1925â1976), were only slightly overshadowed by his most popular of calendar works: the "Four Seasons" illustrations for Brown & Bigelow that were published for 17 years beginning in 1947. Illustrations for booklets, catalogs, posters (particularly movie promotions), sheet music, stamps, playing cards, and murals (including Yankee Doodle Dandy, which was completed in 1936 for the Nassau Inn in Princeton, New Jersey) rounded out Rockwell's oeuvre as an illustrator.

Rockwell married his third wife, retired school teacher Molly Punderson in 1961. He met her at a poetry class that he was attending while coping with the death of his wife and with his declining work load for the Post. (His final cover was published in 1963.)

What enabled Rockwell to continue, at the age of 70, to have a long and prolific career was the fact that his approach to his craft grew and changed with the times. First, he progressed from small things like using photography in place of models to painting themes with more social relevance. In his later works, even facial expressions are more serious and themes that had always been important to him were now updated and showed a different perspective. Rockwell, through his work in the 1960s, addressed the concerns that were especially dire to Americans: issues like civil rights, space exploration, and poverty. During the next decade he would draw more attention as a serious painter.

A new relationship with Look Magazine afforded him the opportunity to work on special assignments, and his art took off in a new direction. His first major work of the decade was The Golden Rule painted in 1960. (Rockwell has a cameo appearance in this painting. He often humorously and in a self-depreciating manner painted himself incognito into his pictures. However, on a more bittersweet note, his wife Mary, who had recently died, is also in the picture holding the grandchild, born after she died, that she never got to see.)

One important piece was inspired by the unjust murders of three civil rights workers near Philadelphia, Mississippi. The painting, Southern Justice, was done in 1965 and depicts the horror endured by three young men, two white and one black, who had come to Mississippi to aid in the fight for equality. Another painting The Problem We All Live With depicts a young African-American girl, Ruby Bridges, flanked by white federal marshals, walking to school past a wall defaced by racist graffiti. It is probably not an image that could have appeared on a magazine cover earlier in Rockwell's career, but it ranks among his best-known works today.

These were among his most gripping and powerful illustrations for Look.

End of Life and Legacy

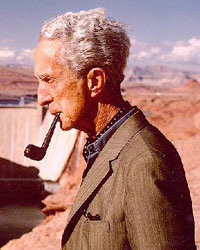

Rockwell's final painting was done for the bicentennial issue of American Artist magazine (1976). It is a self-portrait of the artist, looking like a quintessential grey-haired grandfather smoking a pipe, and draping a birthday ribbon around the Liberty Bell.

Rockwell is a recipient of the Silver Buffalo Award, the highest adult award given by the Boy Scouts of America.

In 1977 he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Gerald Ford for "vivid and affectionate portraits of our country," the United Statesâ highest civilian honor.

Norman Rockwell died November 8, 1978, of emphysema at age 84 in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Characteristically, an unfinished painting rested on his easel.

A custodianship of 574 of his original paintings and drawings was established with Rockwell's help near his home in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, with the Stockbridge Historical Society, who founded the Norman Rockwell Museum.

In November of 2006, Rockwellâs Breaking Home Ties (1954), a Saturday Evening Post cover depicting a Depression-era rancher sending his son off to college, was sold by Sotheby's of New York for $15.4 million, more than double the presale high estimate of $6 million. The painting was found hidden behind a wallâthe late owner, who had bought the work from the artist in 1960 for $900, had presumably secreted it there during a divorce. The Rockwell auction record was previously $9.2 million, set only six months prior to this sale. The buyer was believed to be Alice Walton, the Wal-Mart heiress.

Critique of his work

With over 4,000 original works Rockwell was very prolific. Original magazines in mint condition that contain his work are extremely rare and can command thousands of dollars today.

Many of his works appear overly sweet in modern critics' eyes, especially the Saturday Evening Post covers, which tend toward idealistic or sentimentalized portrayals of American lifeâthis has led to the often-deprecatory adjective "Rockwellesque." Consequently, Rockwell is not considered a "serious painter" by some contemporary artists, who often regard his work as "bourgeois" and "kitsch." He is called an "illustrator" instead of an artist by some critics, a designation he did not mind, as it was what he called himself.

Rockwell sometimes produced images considered powerful and moving to anyone's eye. If there was such a thing as the Great Age of Illustration, as Rockwell believed there was, then his work came at the tail end of that era. Rockwell sought to please his audience, and working in advertising, particularly before the advent of television, required that of him. Later works that explored social themes illustrate how much he grew and changed as an artist through a tumultuous era in American history.

Major works

- Scout at Ship's Wheel (1913) [1]

- Santa and Scouts in Snow (1913) [2]

- Boy and Baby Carriage (1916) [3]

- Circus Barker and Strongman (1916) [4]

- Gramps at the Plate (1916) [5]

- Redhead Loves Hatty Perkins (1916) [6]

- People in a Theatre Balcony (1916) [7]

- Cousin Reginald Goes to the Country (1917) [8]

- Santa and Expense Book (1920) [9]

- Mother Tucking Children into Bed (1921) [10]

- No Swimming (1921) [11]

- The Four Freedoms (1943) [12]

- Freedom of Speech (1943) [13]

- Freedom to Worship (1943) [14]

- Freedom from Want (1943) [15]

- Freedom from Fear (1943) [16]

- Rosie the Riveter (1943) [17]

- Going and Coming (1947)

- Bottom of the Sixth (1949) [18]

- Saying Grace (1951)

- Girl at Mirror (1954)

- Breaking Home Ties (1954) [19]

- The Marriage License (1955)

- The Scoutmaster (1956) [20]

- Triple Self-Portrait (1960) [21]

- Golden Rule (1961)

- The Problem We All Live With (1964) [22]

- New Kids in the Neighborhood (1967)

- The Rookie

- Judy Garland (1969)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Buechner, Thomas S. 1972. Norman Rockwell, A Sixty Year Retrospective. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0810981505

- Claridge, Laura. 2001. Norman Rockwell: A Life. Random House. ISBN 0375504532

- Meyer, Susan E. 1981. Norman Rockwell's People. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0810917777

- Rockwell, Norman. 1988. Norman Rockwell: My Adventures as an Illustrator. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0810925966

External links

All links retrieved November 15, 2022.

- Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, Massachusetts

- Norman Rockwell Museum of Vermont

- Best Norman Rockwell Art

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.