Tibetan art

Tibetan art, or âHimalayan art,â refers to the art of Tibet and other present and former Himalayan kingdoms (Bhutan, Ladakh, Nepal, and Sikkim). Tibetan art is primarily sacred art, drawing elements from the religions of Buddhism, Hinduism, Bon, and various tribal groups, and reflecting the over-riding influence of Tibetan Buddhism. Styles and subject matter can be identified by their composition and use of symbols and motifs. Individual paintings, sculptures and ritual objects are typically created as components of a much larger work such as an altar or the interior of a shrine. The earliest Tibetan art is pictures drawn with sculpted lines on rocks and cliff faces. Later rock art shows Buddhist influences. The iconographic art of India entered Tibet along with Buddhism in the ninth century and was gradually modified to include Tibetan themes and influences from Persia and China.

Until the mid-twentieth century, nearly all Tibetan paintings were religious. Tibetan visual art consists primarily of murals, thangka (painted religious scrolls), Buddhist sculpture and ritual objects, and was primarily created to be used in religious rituals and education. China's Cultural Revolution resulted in the deterioration or loss of traditional art in Buddhist monasteries, both by intentional destruction or through lack of protection and maintenance; an international effort is underway to restore the surviving monasteries and their contents.

Overview

The majority of surviving Himalayan artworks created before the mid-twentieth century are dedicated to the depiction of religious subjects and subject matter drawn from the rich panoply of religious texts. They were commissioned by religious establishments or by pious individuals for use within the practice of Tibetan Buddhism and, despite the existence of flourishing workshops, the artists were largely anonymous. Tibetan artists followed rules specified in the Buddhist scriptures regarding proportions, shape, color, stance, hand positions, and attributes in order to personify correctly the Buddha or deities. It is difficult to precisely date art objects because their creators conservatively followed the same artistic conventions for generations.

Many individual paintings, sculptures and art objects were created as components of a much larger work of art, such as an altar or the interior decoration of a temple or palace.[1]

Tibetan art can be identified by the composition of paintings, and the use of symbols and motifs unique to the individual Himalayan regions, as well as the artistic and cultural elements derived from other great neighboring civilizations. These works not only document key philosophical and spiritual concepts but also illustrate the development of particular schools and the cross-fertilization of stylistic influences from other countries such as China, Nepal and India.

Tibetan visual art consists primarily of murals; thangka (painted religious scrolls); Buddhist sculpture and ritual objects; and rugs, carvings and ornamentations found in temples and palaces.

History

The artistic traditions of Bön, the indigenous religion of the Himalayas, were overwhelmed by the iconographical art of Buddhism, which came to Tibet from India in the ninth century. Some of the earliest Buddhist art is found in the temples built by King SongtsĂ€n Gampo (r. 608 â 649 C.E.) to house the family shrines of his Nepalese and Chinese wives, who were both Buddhists. His great-grandson, Trisong Detsen (r. 755 â 797 or 804), invited the great Indian spiritual masters Padmasambhava (better known as Guru Rinpoche) and Santaraksita to Tibet, established Buddhism as the national religion, and built the first Buddhist monastery, Samye Monastery. The first documented dissemination of Ch'an Buddhism from China to Tibet also occurred during his reign. [2][3] Eighty Châan masters came to teach in central Tibet. During a campaign to expand his domain westward, Trisong Detsen sacked a Persian religious establishment at a place called Batra, and brought back Persian art and ritual objects as well as Persian master craftsmen[4].

Chinese painting had a profound influence on Tibetan painting. Starting from the fourteenth and fifteenth century, Tibetan painting incorporated many elements from the Chinese, and during the eighteenth century, Chinese painting had a deep and far-stretched impact on Tibetan visual art.[5]

Religious influences

Mahayana Buddhist influence

As Mahayana Buddhism emerged as a separate school in the fourth century B.C.E. it emphasized the role of bodhisattvas, compassionate beings who forego their personal escape to Nirvana in order to assist others. From an early time various bodhisattvas were subjects of Buddhist statuary art. Tibetan Buddhism, an offspring of Mahayana Buddhism, inherited this tradition, but Vajrayana (Tantric Buddhism) had an overriding importance in the artistic culture. A common bodhisattva depicted in Tibetan art is the deity Chenrezig (Avalokitesvara), often portrayed as a thousand-armed saint with an eye in the middle of each hand, representing the all-seeing compassionate one who hears our requests. This deity can also be understood as a Yidam, or 'meditation Buddha' for Vajrayana practice.

Tantric influence

Tibetan Buddhism encompasses Tantric Buddhism, also known as Vajrayana Buddhism for its common symbolism of the vajra, the diamond thunderbolt (known in Tibetan as the dorje). Most of the typical Tibetan Buddhist art can be seen as part of the practice of tantra. Vajrayana techniques incorporate many visualizations/imaginations during meditation, and most of the elaborate tantric art can be seen as aids to these visualizations; from representations of meditational deities (yidams) to mandalas and all kinds of ritual implements.

A surprising aspect of Tantric Buddhism is the common representation of wrathful deities, often depicted with angry faces, circles of flame, or with the skulls of the dead. These images represent the Protectors (Skt. dharmapala) and their fearsome bearing belies their true compassionate nature. Their wrath represents their dedication to the protection of the dharma teaching, as well as the protection of specific tantric practices from corruption or disruption. They symbolize wrathful psychological energy that can be directed to conquer the negative attitudes of the practitioner.

Bön influence

Bön, the indigenous shamanistic religion of the Himalayas, contributes a pantheon of local tutelary deities to Tibetan art. In Tibetan temples (known as lhakhang), statues of the Buddha or Padmasambhava are often paired with statues of the tutelary deity of the district who often appears angry or dark. These gods once inflicted harm and sickness on the local citizens, but after the arrival of the tantric mystic Padmasambhava during the reign of Tibetan King Khri srong lde btsan (742â797) these negative forces were subdued and now must serve Buddha.

Traditional visual art

Painting

Rock paintings

Over 5000 rock paintings in the cliffs and caves in the middle and upper reaches of Yarlung Tsangpo River remained undiscovered until the latter part of the twentieth century. The paintings depict humans, plants, trees, weapons, vessels, symbols, and animals including yaks, ox, sheep, horses, dogs, wolves, deer, leopards, and camels. The subject matter includes herding, hunting, fighting, dancing and religious activities related to Tibet's indigenous religion, Bon. Later rock paintings also include Buddhist themes and symbols, like the adamantine pestle, prayer flags, umbrellas, stupas, swastikas, fire, lotuses and scenes of worship and other religious activities. Sculptures of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas are among the more recent rock paintings. The earliest rock paintings, created around 3000 years ago, are symbols sculpted in single thick lines. Rock paintings dating from the first century C.E. to around 1000 C.E. are prolific in the western regions of Tibet and contain large scenes, such as dances and sacrificial ceremonies. These paintings are mostly sculpted lines, but colored pigments began to be applied. Late rock paintings show religious symbols and sacrifices as well as aspects of the Buddhist culture.[6]

Murals

Murals illustrating religious teachings, historical events, legends, myths and the social life of Tibetans ornament the walls, ceilings and passages of Tibetan temples and palaces. Some early murals are devoted to Bon, but most are of religious figures, such as Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Guardians of Buddhist Doctrines, Taras in the sutras, or Buddhist masters. Each can be identified by particular characteristics such as posture, hand gestures, color and accessories that were traditionally associated with it. Typically, a prominent central figure is surrounded by other deities or humans, or by extravagantly detailed settings. The murals of certain temples illustrate Tibetan legends or follow the lives of important figures like Sakyamuni, the founder of Buddhism.

Murals also depict significant historical events and persons, such as the ancient Tibetan kings, Songtsen Gampo (617-650), Trisong Detsen (742-798) and Tri Ralpa Chen (866-896) of Tubo Kingdom, and their famous concubines, Princess Wencheng and Princess Jincheng of Tang Dynasty (618-907) and Princess Bhrikuti of Nepal. Murals painted between 1000 and 1400 C.E. featured numerous portraits of prominent individuals, with stylized details such as halos to indicate royal, noble or saintly persons.[7]

Some murals feature the social life of Tibetans. A group of murals in Jokhang Temple shows people singing, dancing, playing musical instruments and engaging in sporting matches. Murals of folk sport activities and acrobatics are painted on the walls of Potala Palace and Samye Monastery. Many large palaces or temples have murals that describe their entire architectural design and construction process. These murals can be found in Potala, Jokhang, Samye Temple, Sakya Monastery and other famous buildings in Tibet.[8]

Thangka

A thangka, also known as tangka, âthanka,â or âtanka,â is a painted or embroidered Buddhist banner which was hung in a monastery or over a family altar and occasionally carried by monks in ceremonial processions. It can be rolled up when not required for display, and is sometimes called a scroll-painting. Thangka painting was popular among traveling monks because the scroll paintings were easily rolled and transported from monastery to monastery. These thangka served as important teaching tools depicting the life of the Buddha, various influential lamas and other deities and bodhisattvas. One popular subject is the Wheel of Life, a visual representation of the Abhidharma teachings (Art of Enlightenment). The devotional images acted as centerpieces during rituals or ceremonies and were often used as mediums through which to offer prayers or make requests. The visually and mentally stimulating images were used as a focus meditation practice, to bring the practitioner closer to enlightenment.

Thangkas can be painted on paper, loosely-woven cotton cloth, or silk, or made by appliquĂ© (go-tang) or with embroidery (tshim-tang). Painted thangkas are done on treated cotton canvas or silk with water soluble pigments, both mineral and organic, tempered with a herb and glue solution. The entire process demands great mastery over the drawing and a profound understanding of iconometric principles. The artist must paint according to certain basic rules that dictate the number of hands, the color of the deityâs face, the posture of the deity, the holding of the symbols and the expression of the face. Final touches may be added using 24-carat gold. The composition of a thangka is highly geometric. Arms, legs, eyes, nostrils, ears, and various ritual implements are all laid out on a systematic grid of angles and intersecting lines. A skilled thangka artist generally includes a variety of standardized items ranging from alms bowls and animals, to the shape, size, and angle of a figure's eyes, nose, and lips, in the composition.

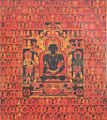

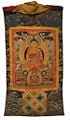

Seventeenth century Central Tibetan thanka of Guhyasamaja Akshobhyavajra, Rubin Museum of Art

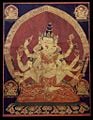

Eighteenth century Eastern Tibeten thanka, with the Green Tara (Samaya Tara Yogini) in the center and the Blue, Red, White and Yellow taras in the corners, Rubin Museum of Art

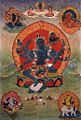

Bhutanese Drukpa Kagyu applique Buddhist lineage thanka with Shakyamuni Buddha in center, 19th century, Rubin Museum of Art

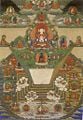

Bhutanese painted thanka of Guru Nyima Ozer, late 19th century, Do Khachu Gonpa, Chukka, Bhutan

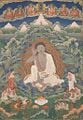

Bhutanese painted thanka of Milarepa (1052-1135), late 19th-early 20th century, Dhodeydrag Gonpa, Thimphu, Bhutan

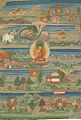

Bhutanese painted thanka of the Jataka Tales, 18th-19th century, Phajoding Gonpa, Thimphu, Bhutan

Mandala

A kyil khor (Tibetan for mandala) in Vajrayana Buddhism usually depicts a landscape of the Buddha-land or the enlightened vision of a Buddha. It consists of an outer circular mandala and an inner square (or sometimes circular) mandala with an ornately decorated mandala palace[9] placed at the center. Any part of the inner mandala can be occupied by Buddhist glyphs and symbols [10] as well as images of its associated deities, to represent different stages in the process of the realization of the truth. Every intricate detail is fixed by tradition and has specific symbolic meanings, often on more than one level.

Mandalas are commonly used by tantric Buddhists as an aid to meditation. More specifically, a Buddhist mandala is envisaged as a "sacred space," a Pure Buddha Realm[11] and also as an abode of fully realized beings or deities.

A mandala can also represent the entire Universe, which is traditionally depicted with Mount Meru as the axis mundi in the center, surrounded by the continents. A 'mandala offering' [12] in Tibetan Buddhism is a symbolic offering of the entire Universe.

Sand mandala

The sand Mandala is a Tibetan Buddhist tradition involving the creation and destruction of mandalas made from colored sand.

Traditionally the sand mandala was created with granules of crushed colored stone. In modern times, plain white stones are ground down and dyed with opaque inks to achieve the same effect. Monks carefully draw the geometric measurements associated with the mandala, then painstakingly apply the sand granules using small tubes, funnels, and scrapers, working from the center outward until the desired pattern over-top is achieved. Most sand mandalas take several weeks to build, due to the large amount of work involved in laying down the sand in such intricate detail.

The Kalachakra Mandala contains 722 deities portrayed within the complex structure and geometry of the mandala itself. Smaller mandalas, like the one attributed to Vajrabhairava contain fewer deities and require less geometry.

A sand mandala is ritualistically destroyed once it has been completed and its accompanying ceremonies and viewing are finished, to symbolize the Buddhist doctrinal belief in the transitory nature of material life. The deity syllables are removed in a specific order, and the sand is collected in a jar which is then wrapped in silk and transported to a river, where it is gradually released into the moving water.

Sculpture

Surviving Pre-Buddhist carved stone pillars from the seventh to ninth centuries are decorated with Chinese, Central Asian, and Indian motifs and also a stone lion showing traces of Persian influence.

The technique of casting figures in bronze and other metals entered Tibet from Nepal and India. Tibetan artists gradually developed their own styles and began to depict their own lamas and teachers as well as the vast pantheon of Buddhas, gods, and goddesses inherited from India. The iconic postures, hand gestures, and accessories specified by Buddhist scriptures identify each sculpture as a specific deity or type of saint. Tibetan temples often contain very large sculptural images, several stories tall. The statue of Maitreya Buddha in Tashilhunpo Monastery, which is 26.2 m. (86 ft.) high, is the largest seated bronze Buddhist statue in the world.[13]

The themes of Tibetan sculpture are Buddhist sutras; Buddhist figures, such as Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Heavenly Kings, Vajras, Buddhist masters and famous historical figures; religious symbols; and auspicious animals and plants. These themes are found not only in religious statues, objects and offerings, but also in the Tibetan furniture, ornaments and articles for daily use.[13]

Carving is restricted to decorative motifs, especially on wooden pillars, roof beams, window frames and furniture. Bone, horn and shell are used in the creation of holy relics. Temporary sculptures of yak butter are created for religious festivals. The use of papier-mùché, elaborately painted, for masks of divinities, is thought to have originated in Kashmir.

Clay and terra cotta sculptures of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Buddhist masters, Guardians of Buddhist Doctrines, stupas, animals and other figures are common in Tibetan temples and monasteries. Statues of the chief deities and their companions are usually several meters tall and appear life-like. Tsa-tsas, miniature Buddha figures and stupas molded with clay are used as holy objects and amulets. The earliest stone sculptures in Tibet were made during the Tubo Kingdom; the most well-known are two lion statues in the Graveyard of Tibetan Kings.[13]

Metal work

References in historical documents indicate the Tibetan metal workers produced beautiful objects in gold and silver long before Buddhism came to Tibet. Objects are commonly made of bronze, brass or copper, sometimes of gold, silver or iron. Metalworkers have made ritual lamps, vases, bowls, stupas, bells, prayer wheels, mandalas and decorated trumpets and horns, for the temples; and jewelry, ornamented teapots, jars, bowls, ladles, and especially beautiful stands, often in silver or gold, to hold porcelain teacups, capped by finely worked lids of precious metals for domestic use.[13]

Contemporary Tibetan art

Tibetâs vibrant modern art scene exhibits three artistic tendencies. Some artists have returned to the traditionalist styles of their forefathers, painting thangka (religious scroll paintings) that retain the iconographic and aesthetic qualities of earlier work. Others follow a 'middle way' combining lessons from the art of the past with motifs and techniques that reflect Tibetâs modernity. Another group is inventing a completely new type of Tibetan painting which draws inspiration from contemporary art movements in Asia and the West to produce radical, even avant-garde, works. All three approaches are to some extent engaged in a dialogue with the past and with the works of Tibetan artists of previous centuries

Literature

The earliest Tibetan writing dates to the eighth century C.E. Many Indian and Chinese texts were translated and copied, and some that would otherwise have been lost have been preserved in Tibetan.

There is a rich ancient tradition of lay Tibetan literature which includes epics, poetry, short stories, dance scripts and mime, and plays which has expanded into a huge body of work, some of which has been translated into Western languages. Perhaps the best known category of Tibetan literature outside of Tibet are the epic stories, particularly the famous Epic of King Gesar.

Drama

The Tibetan folk opera, known as Ache Lhamo, which literally means "sister goddess," is a combination of dances, chants and songs. The repertoire is drawn from Buddhist stories and Tibetan history. Llhamo is held on various festive occasions such as the Linka and Shoton festivals. The performance is usually held on a barren stage. Colorful masks are sometimes worn to identify a character, with red symbolizing a king and yellow indicating deities and lamas. The performance starts with a stage purification and blessings. A narrator then sings a summary of the story, and the performance begins. Another ritual blessing is conducted at the end of the play.[14].

Architecture

Tibetan architecture contains Chinese and Indian influences, and reflects a deeply Buddhist approach.

The most unique feature of Tibetan architecture is that many of the houses and monasteries are built on elevated, sunny sites facing the south, and are often made out a mixture of rocks, wood, cement and earth. Little fuel is available for heat or lighting, so flat roofs are built to conserve heat, and multiple windows are constructed to let in sunlight. Walls are usually sloped inwards at ten degrees as a precaution against frequent earthquakes in the mountainous area.

Potala Palace

Standing at 117 meters in height and 360 meters in width, the Potala Palace, designated as a World Heritage Site in 1994 and extended to include the Norbulingka area in 2001, is considered a most important example of Tibetan architecture.[15]

Formerly the residence of the Dalai Lama, it contains over a thousand rooms within 13 stories, and houses portraits of the past Dalai Lamas and statues of the Buddha. It is divided into the outer White Palace, which serves as the administrative quarters, and the inner Red Quarters, which houses the assembly hall of the Lamas, chapels, ten thousand shrines and a vast library of Buddhist scriptures.

Traditional architecture

Traditional Kham architecture is seen in most dwellings in Kangding, where wood is used abundantly as a building material. The roof is supported by horizontal timber beams, which rest on wooden columns. Floors and ceilings are wooden. The interior of houses are usually paneled with wood and the cabinetry is ornately decorated. Ganzi, Kham, is known for its beautiful wooden houses built in a range of styles and lavishly decorated with wooden ornamentation.[16]

Religious architecture

According to the Buddhist sutras the universe is composed of four large continents and eight small continents, with Mount Meru at the center. This cosmology is incorporated in the design of Tibetan monasteries. A unique feature of Tibetan temples is golden roofs decorated with many holy or auspicious subjects such as lotuses, stupas, dharma wheels, inverted bells, prayer flags and animals.[17] The monasteries, which began to be built were modeled on the palaces of Tibetan royalty. Even the interior designs and seating arrangements were copied from the audience halls of Tibetan kings. Iconographical subjects were painted on the walls as frescoes and three-dimensional shrines were built and sculptured images of deities placed upon them.[4] The Buddhist Prayer wheel, along with two deer or dragons, can be seen on nearly every Gompa (monastery) in Tibet. The design of the Tibetan chörtens (stupas) varies from roundish walls in Kham to squarish, four-sided walls in Ladakh.

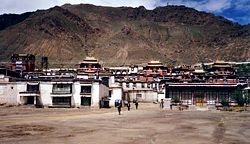

Tashilhunpo Monastery shows the influence of Mongol architecture. Changzhug monastery is one of the oldest in Tibet, said to have been first built in the seventh century during the reign of King Songsten Gampo (605?-650 C.E.). Jokhang was also originally built under Songsten Gampo. Tsurphu Monastery was founded by the first Karmapa, DĂŒsum Khyenpa (1110-1193) in 1159, after he visited the site and laid the foundation for an establishment of a seat there by making offerings to the local protectors, dharmapala and genius loci.[18]Tsozong Gongba Monastery is a small shrine built around fourteenth century C.E. Palcho Monastery was founded in 1418 and known for its kumbum which has 108 chapels on its four floors. Chokorgyel Monastery, founded in 1509 by Gendun Gyatso, 2nd Dalai Lama once housed 500 monks but was completely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution.

Ramoche Temple is an important temple in Lhasa. The original building complex was strongly influenced by Tang Dynasty architectural style as it was first built by Han Chinese architects in the middle of the seventh century. Princess Wencheng took charge of this project and ordered the temple be erected facing east to show her homesickness.

Monasteries such as the Kumbum Monastery continue to be affected by Chinese politics. Simbiling Monastery was completely flattened in 1967, although it has to some degree been restored.

Dzong architecture

Dzong architecture (from Tibetan àœąàŸ«àœŒàœàŒ, Wylie rDzong) is a distinctive type of fortress architecture found in the former and present Buddhist kingdoms of the Himalayas, most notably Bhutan. The architecture is massive in style with towering exterior walls surrounding a complex of courtyards, temples, administrative offices, and monks' accommodation. Dzongs serve as the religious, military, administrative, and social centers of their districts. Distinctive features include:

- High inward sloping walls of brick and stone painted white, surrounding one or more courtyards, with few or no windows in the lower sections of the wall

- Use of a surrounding red ochre stripe near the top of the walls, sometimes punctuated by large gold circles.

- Use of Chinese-style flared roofs atop interior temples.

- Massive entry doors made of wood and iron

- Interior courtyards and temples brightly colored in Buddhist-themed art motifs such as the ashtamangala or swastika.

Traditionally, dzongs are constructed without the use of architectural plans. Instead construction proceeds under the direction of a high lama who establishes each dimension by means of spiritual inspiration.

The main internal structures are built with stone or rammed clay blocks), and whitewashed inside and out, with a broad red ochre band at the top on the outside. The larger spaces such as the temple have massive internal timber columns and beams to create galleries around an open central full height area. Smaller structures are of elaborately carved and painted timber construction. The massive roofs as constructed of hardwood and bamboo, without the use of nails, and are highly decorated at the eaves.

Music

The music of Tibet reflects the cultural heritage of the trans-Himalayan region, centered in Tibet but also known wherever ethnic Tibetan groups are found in India, Bhutan, Nepal and further abroad. Tibetan music is primarily religious music, reflecting the profound influence of Tibetan Buddhism on the culture.

Chanting

Tibetan music often involves complex chants in Tibetan or Sanskrit, recitations of sacred texts or celebration of various religious festivals. Yang chanting, performed without metrical timing, is accompanied by resonant drums and low, sustained syllables. Other styles include those unique to the various schools of Tibetan Buddhism, such as the classical music of the popular Gelugpa school, and the romantic music of the Nyingmapa, Sakyapa and Kagyupa schools.

Secular Tibetan music has been promoted by organizations like the Dalai Lama's Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts. This organization specialized in the lhamo, an operatic style, before branching out into other styles, including dance music like toeshey and nangma. Nangma is especially popular in the karaoke bars of the urban center of Tibet, Lhasa. Another form of popular music is the classical gar style, which is performed at rituals and ceremonies. Lu are a type of songs that feature glottal vibrations and high pitches. There are also epic bards who sing of Tibet's national hero Gesar.

Modern and popular

Tibetans are well-represented in Chinese popular culture. Tibetan singers are particularly known for their strong vocal abilities, which many attribute to the high altitudes of the Tibetan Plateau. Tibetan music has had a profound effect on some styles of Western music, especially New Age. Foreign styles of popular music have also had a major impact within Tibet. Indian ghazal and filmi are very popular, as is rock and roll. Since the relaxation of some laws in the 1980s, Tibetan pop, has become popular.

See also

Notes

- â Definition: Himalayan 'Style' Art Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- â Chronicled in what has become known as the Statements of the Sba Family, this occurred in c. 761 C.E. when Trisong Detsen sent a party to the I-chou region to receive teachings of Reverend Kim (Chin ho-shang), a Korean Ch'an master, whom they encountered in Szechuan. The party received teachings and three Chinese texts from Reverend Kim. Reverend Kim died soon after.

- â Gary L. Ray. 2005. The Northern Ch'an School and Sudden Versus Gradual Enlightenment Debates in China and Tibet. Source: [1] Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- â 4.0 4.1 Background and History: Visual Dharma: the Buddhist Art of Tibet Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- â Alex McKay. The History of Tibet. (New York: Routledge, 2003), 596-597. ISBN 0700715088 âAccording to Giuseppe Tucci, by the time of the Qing Dynasty, "a new Tibetan art was then developed, which in a certain sense was a provincial echo of the Chinese eighteenth century's smooth ornate preciosity."

- â Rock paintings TibetTrip. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- â Jane Casey Singer, November 30, 1996, Early Portrait Painting in Tibet, This article, based on a lecture delivered to a symposium held in Leiden on the function and meaning of Buddhist art, appears in a book entitled Function and Meaning in Buddhist Art, edited by K.R. van Kooij and H. van der Veere. (Gonda Indological Series, vol. 2) (Groningen: E. Forsten, 1995). Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- â Murals Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- â Jytte Hansen, Albertslund, Denmark, Mandala Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- â Jytte Hansen, Symbols Mandala. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- â Chökyi Drakpa, Offering the Mandala, Lotsawa House. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- â Alexander Berzin, December 2003, The Meaning and Use of a Mandala The Berzin Archives. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- â 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Sculptures. TibetTrip. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- â R. A. Stein, Tibetan Civilization. (1962 in French). First English edition with minor changes 1972). (Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804708061), 248-281.

- â Historic Ensemble of the Potala Palace, Lhasa. UNESCO World Heritage. Retrieved February 9, 2009

- â Pamela Logan, 1998, [2] Wooden Architecture in Ganzi. Asian Arts, online journal. Retrieved February 9, 2009

- â Architecture. TibetTrip. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- â Tsurphu Monastery - The Main Seat Of The Karmapa. Karmapa's Office of Administration. Retrieved February 9, 2009

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Amundsen, Ingun B., On Bhutanese and Tibetan Dzongs in Journal of Bhutan Studies 5 (Winter 2001): 8-41 Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- Bernier, Ronald M. Himalayan Architecture. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. 1997. ISBN 9780838636022.

- Chandra, Lokesh. Tibetan art. New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2008. ISBN 9788189738303.

- Chophel, Norbu. Folk Tales of Tibet. Dharamsala, H.P., India: Library of Tibetan Works & Archives, 1984, Reprinted 1989, 1993. ISBN 81-85102260.

- Function and Meaning in Buddhist Art, edited by K.R. van Kooij and H. van der Veere. (Gonda Indological Series, vol. 2) Groningen: E. Forsten, 1995. ISBN 9069800799. in English.

- Lipton, Barbara, and Nima Dorjee Ragnubs. Treasures of Tibetan Art: Collections of the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 0195097149.

- McKay, Alex. The History of Tibet. annotated edition. New York: Routledge, 2003. ISBN 0700715088.

- Stein, R. A. Tibetan Civilization. (1962 in French). First English edition with minor changes 1972). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804708061.

- Tarthang Tulku. Art of Enlightenment: A perspective on the Sacred Art of Tibet. (Yeshe De Project. Sacred art portfolio series.) Berkeley, CA: Dharma Pub., 1987. ISBN 9780898001723.

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2023.

- Database of 25,000 pieces of Himalayan art (Tibetan, Nepalese, Bhutanese, Indian, Chinese, Sikkimese, Mongolian, and Gandharan)

- Video of interview with Richard Ernst, Nobel Laureate and scientist with a passion for Tibetan art (RealPlayer required - art discussion begins at about 49 minutes)

- More than 4500 pages of sacred Tibetan art from Dharmapala Thangka Centre - Kathmandu | Nepal

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Tibetan_art history

- Sand_mandala history

- Thangka history

- Dzong_architecture history

- Mandala history

- Contemporary_Tibetan_art history

- Tibetan_culture history

- Ralung_Monastery history

- Guge history

- Chokpori history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.