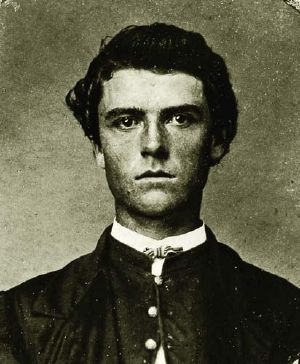

| William Frederick Cody | |

|---|---|

| February 26, 1846 ‚Äď January 10, 1917) | |

Buffalo Bill Cody | |

| Nickname | Wild Bill |

| Place of birth | near Le Claire, Iowa |

| Place of death | Denver, Colorado |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/branch | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1863-1866 |

| Battles/wars | Civil War |

| Awards | Medal of Honor |

| Other work | After being a frontiersman, Buffalo Bill entered show business |

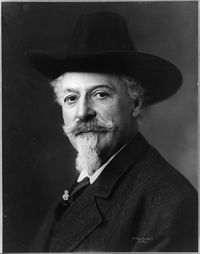

William Frederick "Buffalo Bill" Cody (February 26, 1846 ‚Äď January 10, 1917) was an American soldier, bison hunter and showman. He was born in the American state of Iowa, near Le Claire. He was one of the most colorful figures of the Old West, and is mostly famous for the shows he organized with cowboy themes. Buffalo Bill is a recipient of the Medal of Honor. Cody is an almost iconic figure in the development of the a home-grown American culture and sense of identity yet in contrast to his image and stereotype as a rough-hewn outdoorsman, Buffalo Bill pushed for the rights of American Indians and for those of women. In addition, despite his history of killing bison, he supported their conservation by speaking out against hide-hunting and by pushing for a hunting season.

The West was regarded as territory that needed to be tamed, settled and made part of the American dream, where life, liberty and confederal democracy would take root. At the same time, as opposed to the Old World where class and privilege counted for so much, the United States saw itself as a space where anyone, by dint of hard work, could create a good life. Cody had minimal education, started to work at the age of eleven, yet earned a Medal of Honor and gained a national reputation as a frontiersman.

Nickname and work life

William Frederick ("Buffalo Bill") Cody got his nickname for supplying Kansas Pacific Railroad workers with bison meat. The nickname originally referred to Bill Comstock. Cody won the nickname from him in 1868 in a bison killing contest.

In addition to his documented service as a soldier during the Civil War and as Chief of Scouts for the Third Cavalry during the Plains Wars, Cody claimed to have worked many jobs, including as a trapper, bullwhacker, "Fifty-Niner" in Colorado, a Pony Express rider in 1860, wagonmaster, stagecoach driver, and even a hotel manager, but it's unclear which claims were factual and which were fabricated for purposes of publicity. He became world famous for his Wild West show.

Early years

William Frederick Cody was born at his family's farmhouse in Scott County, Iowa, near the town of Leclaire, Iowa, on February 26, 1846, to Isaac and Mary Cody, who had married in 1840 in Cincinatti. He was their third child. Isaac had come to Ohio from Canada at the age of 17. When his first wife died, he married Mary and moved with her and his daughter from the previous marriage, Martha, to Iowa to seek prosperity. In 1853, when Cody was 7, his older brother, Samuel (age 12), was killed by a fall from a horse. His death so affected Mary Cody's health that a change of scene was advised and the family relocated to Kansas, moving into a large log cabin on land that they had staked there.[1]

Cody's father believed that Kansas should be a free state, but many of the other settlers in the area were pro-slavery (see Bleeding Kansas). While giving an anti-slavery speech at the local trading post, he so inflamed the supporters of slavery in the audience that they formed a mob and one of them stabbed him. Cody helped to drag his father to safety, although he never fully recovered from his injuries. The family was constantly persecuted by the supporters of slavery, forcing Isaac Cody to spend much of his time away from home. His enemies learned of a planned visit to his family and plotted to kill him on the way. Cody, despite his youth and the fact that he was ill, rode 30 miles (48 km) to warn his father. Cody's father died in 1857 from complications from his stabbing.[2]

After his father's death, the Cody family suffered financial difficulties, and Cody, aged only 11, took a job with freight carrier as a "boy extra," riding up and down the length of a wagon train, delivering messages. From here, he joined Johnston's Army as an unofficial member of the scouts assigned to guide the Army to Utah to put down a falsely-reported rebellion by the Mormon population of Salt Lake City.[3] According to Cody's account in Buffalo Bill's Own Story, this was where he first began his career as an "Indian fighter."

Presently the moon rose, dead ahead of me; and painted boldly across its face was the figure of an Indian. He wore the war-bonnet of the Sioux, at his shoulder was a rifle pointed at someone in the river-bottom 30 feet below; in another second he would drop one of my friends. I raised my old muzzle-loader and fired. The figure collapsed, tumbled down the bank and landed with a splash in the water. "What is it?" called McCarthy, as he hurried back. "It's over there in the water," I answered. McCarthy ran over to the dark figure. "Hi!" he cried. "Little Billy's killed an Indian all by himself!" So began my career as an Indian fighter.[4]

At the age of 14, Cody was struck by gold fever, but on his way to the gold fields, he met an agent for the Pony Express. He signed with them and after building several way stations and corrals was given a job as rider, which he kept until he was called home to his sick mother's bedside.[5]

His mother recovered, and Cody, who wished to enlist as a soldier, but was refused for his age, began working with a United States freight caravan which delivered supplies to Fort Laramie.

Civil War soldier and marriage

Shortly after the death of his mother in 1863, Cody enlisted in the 7th Kansas Cavalry Regiment (also known as Jennison's Jayhawks) and fought with them on the Union side for the rest of the Civil War. His military career was lackluster, with most of his activities relegated to scouting and spying (during which he developed a strong acquaintance with Wild Bill Hickok), and performing non-battlefield related duties.[6]

While stationed at military camp in St. Louis, Bill met Louisa Frederici (1843-1921). He returned after his discharge and they married on March 6, 1866. Their marriage was not a happy one, and Bill unsuccessfully attempted to divorce Louisa after she expressed discontent as to his ability to provide for her financially. They had four children, two of whom died young: his beloved son, Kit died of scarlet fever in April, 1876, and his daughter Orra died in 1880. Their first child was a daughter named Arta; they also had a daughter named Irma.[7]

His early experience as an Army scout led him again to scouting. From 1868 until 1872 Cody was employed as a scout by the United States Army. Part of this time he spent scouting for Indians, and the remainder was spent gathering and killing bison for them and the Kansas Pacific Railroad.

Medal of Honor

He received the Medal of Honor in 1872 for gallantry in action while serving as a civilian scout for the 3rd Cavalry Regiment. This medal was revoked on February 5, 1917, 24 days after his death, because he was a civilian and therefore was ineligible for the award under new guidelines for the award in 1917. The medal was restored to him by the United States Army in 1989.

In 1916, the general review of all Medals of Honor deemed 900 unwarranted. This recipient was one of them. In June 1989, the U.S. Army Board of Correction of Records restored the medal to this recipient:

Citation: Rank: Civilian Scout. Born: Scott County, Iowa. Organization: 3rd Cavalry U.S. Army. Action date: April 26, 1872. Place: Platte River, Nebraska.

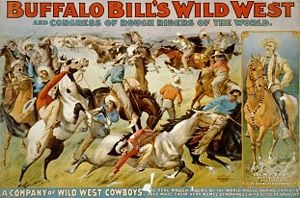

Buffalo Bill's Wild West

After being a frontiersman, Buffalo Bill entered show business. He formed a touring company called the Buffalo Bill Combination which put on plays (such as "Scouts of the Prairie," "Scouts of the Plain") based loosely on his Western adventures, initially with Texas Jack Omohundro, and for one season (1873) with Wild Bill Hickok. The troupe toured for ten years and his part typically included an 1876 incident at the Warbonnet Creek where he claimed to have scalped a Cheyenne warrior, purportedly in revenge for the death of George Armstrong Custer.[8]

It was the age of great showmen and traveling entertainers, like the Barnum and Bailey Circus and the Vaudeville circuits. Cody put together a new traveling show based on both of those forms of entertainment. In 1883, in the area of North Omaha, Nebraska, he founded "Buffalo Bill's Wild West," (despite popular misconception the word "show" was not a part of the title) a circus-like attraction that toured annually.

As the Wild West toured North America over the next twenty years, it became a moving extravaganza, including as many as 1200 performers. In 1893, the title was changed to "Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World." The show began with a parade on horseback, with participants from horse-culture groups that included US and other military, American Indians, and performers from all over the world in their best attire. There were Turks, Gauchos, Arabs, Mongols, and Cossacks, among others, each showing their own distinctive horses and colorful costumes. Visitors to this spectacle could see main events, feats of skill, staged races, and sideshows. Many authentic western personalities were part of the show. For example Sitting Bull and a band of twenty braves appeared. Cody's headline performers were well known in their own right. People like Annie Oakley and her husband Frank Butler put on shooting exhibitions along with the likes of Gabriel Dumont. Buffalo Bill and his performers would re-enact the riding of the Pony Express, Indian attacks on wagon trains, and stagecoach robberies. The show typically ended with a melodramatic re-enactment of Custer's Last Stand in which Cody himself portrayed General Custer.

In 1887, he performed in London in celebration of the Jubilee year of Queen Victoria, and toured Europe in 1889. In 1890, he met Pope Leo XIII. He set up an exhibition near the Chicago World's Fair of 1893, which greatly contributed to his popularity, and also vexed the promoters of the fair. As noted in The Devil in the White City, he had been rebuffed in his request to be part of the fair, so he set up shop just to the west of the fairgrounds, drawing many patrons away from the fair. Since his show was not part of the fair, he was not obligated to pay the fair any royalties, which they could have used to temper the financial struggles of the fair.[9]

Many historians claim that, at the turn of the twentieth century, Buffalo Bill Cody was the most recognizable celebrity on earth and yet, despite all of the recognition and appreciation Cody's show brought for the Western and American Indian cultures, Buffalo Bill saw the American West change dramatically during his tumultuous life. Bison herds, which had once numbered in the millions, were now threatened with extinction. Railroads crossed the plains, barbed wire, and other types of fences divided the land for farmers and ranchers, and the once-threatening Indian tribes were now almost completely confined to reservations. Wyoming's resources of coal, oil and natural gas were beginning to be exploited towards the end of his life.

Even the Shoshone River was dammed for hydroelectric power as well as for irrigation. In 1897 and 1899, Colonel William F. (Buffalo Bill) Cody and his associates acquired from the State of Wyoming the right to take water from the Shoshone River to irrigate about 169,000 acres (684 km²) of land in the Big Horn Basin. They began developing a canal to carry water diverted from the river, but their plans did not include a water storage reservoir. Colonel Cody and his associates were unable to raise sufficient capital to complete their plan. Early in 1903 they joined with the Wyoming Board of Land Commissioners in urging the federal government to step in and help with irrigation development in the valley.

The Shoshone Project became one of the first federal water development projects undertaken by the newly formed Reclamation Service, later to become known as the Bureau of Reclamation. After Reclamation took over the project in 1903, investigating engineers recommended constructing a dam on the Shoshone River in the canyon east of Cody.

Construction of the Shoshone Dam (later called Buffalo Bill Dam) started in 1905, a year after the Shoshone Project was authorized. Almost three decades after its construction the title of dam and reservoir was changed by Act of Congress to Buffalo Bill Dam to honor Cody.

Life in Cody, Wyoming

In 1895, William Cody was instrumental in helping found Cody, Wyoming. Incorporated in 1901, Cody is located 52 miles (84 km) from Yellowstone National Park's east entrance. Cody was founded by Colonel William F. ‚ÄúBuffalo Bill‚ÄĚ Cody who passed through the region in the 1870s. He was so impressed by the development possibilities from irrigation, rich soil, grand scenery, hunting, and proximity to Yellowstone Park that he returned in the mid-1890s to start a town. He brought with him men whose names are still on street signs in Cody‚Äôs downtown area ‚Äď Beck, Alger, Rumsey, Bleistein and Salsbury.[10]

In 1902, he built the Irma Hotel in downtown Cody.[11] The hotel is named after his daughter, Irma. He also had lodging along the North Fork of the Shoshone River, which is a route to the east entrance of Yellowstone National Park that included the Wapiti Inn and Pahaska Teepee. Up the south fork of the Shoshone was his ranch, the TE.[12]

When Cody acquired the TE property, he ordered the movement of Nebraska and South Dakota cattle to Wyoming. This new herd carried the TE brand. The late 1890s were relatively prosperous years for Buffalo Bill's Wild West and he used some of the profits to accumulate lands which were added to the TE holdings. Eventually Cody held around eight thousand acres (32 km²) of private land for grazing operations and ran about a thousand head of cattle. He also operated a dude ranch, pack horse camping trips, and big game hunting business at and from the TE Ranch. In his spacious and comfortable ranch house he entertained notable guests from Europe and America.

Death

Cody died of kidney failure on January 10, 1917, surrounded by family and friends, including his wife, Louisa, and his sister, May, at his sister's house in Denver.[13] Upon the news of his death he received tributes from the King of England, the German Kaiser, and President Woodrow Wilson. [14] His funeral was in Denver at the Elks Lodge Hall. Wyoming Governor John B. Kendrick, a friend of Cody's, led the funeral procession to the Elks Lodge.

Contrary to popular belief Cody was not destitute, but his once great fortune had dwindled to under $100,000. Despite his request to be buried in Cody, Wyoming, in an early will, it was superseded by a later will which left his burial arrangements up to his wife Louisa. To this day there is controversy as to where Cody should have been buried. According to the writer Larry McMurtry, his then partner Harry Tammen, a Denver newspaperman, either "bullied or bamboozled the grieving Louisa" and had Cody buried in Colorado.[15] On June 3, 1917, Cody was buried on Colorado's Lookout Mountain, in Golden, Colorado, west of the city of Denver, located on the edge of the Rocky Mountains and overlooking the Great Plains. While there is evidence that Cody had already been baptized as a baby, he was baptized a Catholic on January 9, 1917, the day before he died. In 1948, the Cody branch of the American Legion offered a reward for the "return" of the body, so the Denver branch mounted a guard over the grave until a deeper shaft could be blasted into the rock. [14]

Legacy

In contrast to his image and stereotype as a rough-hewn outdoorsman, Buffalo Bill pushed for the rights of American Indians and women. In addition, despite his history of killing bison, he supported their conservation by speaking out against hide-hunting and pushing for a hunting season.

Buffalo Bill became so well known and his exploits such a part of American culture that his persona has appeared in many literary works, as well as television shows and movies. Westerns were very popular in the 1950s and 60s. Buffalo Bill would make an appearance in most of them. As a character, he is in the very popular Broadway musical Annie Get Your Gun, which was very successful both with Ethel Merman and more recently with Bernadette Peters in the lead role. On television, his persona has appeared on shows such as Bat Masterson and even Bonanza. His personal appearance has been portrayed everywhere from an elder statesman to a flamboyant, self-serving exhibitionist.

Having been a frontier scout who respected the natives, he was a staunch supporter of their rights. He employed many more natives than just Sitting Bull, feeling his show offered them a better life, calling them "the former foe, present friend, the American," and once said, "Every Indian outbreak that I have ever known has resulted from broken promises and broken treaties by the government."

While in his shows the Indians were usually the "bad guys," attacking stagecoaches and wagon trains in order to be driven off by "heroic" cowboys and soldiers, Bill also had the wives and children of his Indian performers set up camp as they would in the homelands as part of the show, so that the paying public could see the human side of the "fierce warriors," that they were families like any other, just part of a different culture.

The city of Cody, Wyoming, was founded in 1896, by Cody and some investors, and is named for him. It is the home of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center. Fifty miles from Yellowstone National Park, it became a tourist magnet with many dignitaries and political leaders coming to hunt. Bill did indeed spend a great amount of time in Wyoming at his home in Cody. However, he also had a house in the town of North Platte, Nebraska and later built the Scout's Rest Ranch there where he came to be with his family between shows. This western Nebraska town is still home to "Nebraskaland Days," an annual festival including concerts and a large rodeo. The Scout's Rest Ranch in North Platte is both a museum, and a tourist destination for thousands of people every year.

Buffalo Bill became a hero of the Bills, a Congolese youth subculture of the late 1950s who idolized Western movies.

In film and television

Buffalo Bill has been portrayed in the movies by:

|

|

|

"Buffalo Bill's/defunct"

A famous free verse poem on mortality by E. E. Cummings uses Buffalo Bill as an image of life and vibrancy. The poem is generally untitled, and commonly known by its first two lines: "Buffalo Bill's/defunct," however some books such as "Poetry" edited by J. Hunter uses the name "portrait." The poem uses expressive phrases to describe Buffalo Bill's showmanship, referring to his "watersmooth-silver / stallion," and using a staccato beat to describe his rapid shooting of a series of clay pigeons. The poem which featured this character caused great controversy. Buffalo Bill was actually in debt at the time of his death which is why the word "defunct" used in the second verse is so affective. The fusion of words such as "onetwothreefour" interprets the impression in which Buffalo Bill left on his audiences.

Other Buffalo Bills

- Buffalo Bill is also the name of a fictional character from Thomas Harris's The Silence of the Lambs, who was also parodied in the movie Joe Dirt under the name Buffalo Bob.

- Two television series, Buffalo Bill, Jr. (1955‚Äď6) starring Dickie Jones and Buffalo Bill (1983‚Äď4) starring Dabney Coleman, had nothing to do with the historic person.

- The Buffalo Bills, an NFL team based in Buffalo, New York, were named after Buffalo Bill. Prior to that team's existence, other early football teams (such as Buffalo Bills (AAFC)) used the nickname, solely due to name recognition, as Bill Cody had no special connection with the city.

- The Buffalo Bills are a barbershop-quartet singing group consisting of Vern Reed, Al Shea, Bill Spangenberg, and Wayne Ward. They appeared in the original Broadway cast of The Music Man (opened 1957) and in the 1962 motion-picture version of that play.

- "Buffalo Bill" is the title of a song by the jam band Phish.

- Buffalo Bill is the name of a bluegrass band in Wisconsin

- Samuel Cowdery, buffalo hunter, "wild west" showman and aviation pioneer changed his surname to "Cody" and was often taken for the original "Buffalo Bill" in his touring show Captain Cody King of the Cowboys.

Further reading

- "Buffalo Bill Days." The Sheridan Press, June 22-24, 2007. A 20-page special section published in June 2007 by Sheridan Newspapers, Inc., 144 Grinnell Avenue, Post Office Box 2006, Sheridan, Wyoming, 82801, USA. (Includes extensive information about Buffalo Bill, as well as the schedule of the annual three-day event held in Sheridan, Wyoming.)

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Louis S. Warren, Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody and the Wild West Show (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 8.

- ‚ÜĎ Warren, 9-13.

- ‚ÜĎ Warren, 14.

- ‚ÜĎ William F. Cody, Buffalo Bill's Own Story (Chicago: John R. Stanton, 1917).

- ‚ÜĎ Warren, 22-25.

- ‚ÜĎ Warren, 37-38.

- ‚ÜĎ Warren, 44-45.

- ‚ÜĎ Melvin Schulte, Buffalo Bill as Reported in Newspapers. Retrieved September 8, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Warren, 282-339.

- ‚ÜĎ Warren, 473-474.

- ‚ÜĎ Warren, 474.

- ‚ÜĎ Warren, 488.

- ‚ÜĎ Warren, 541.

- ‚ÜĎ 14.0 14.1 John Lloyd and John Mitchinson, The Book of General Ignorance (London: Faber & Faber, 2006).

- ‚ÜĎ Larry McMurtry, Sacagawea's Nickname (New York: New York Review of Books, 2001).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cody, William F. Buffalo Bill's Own Story. Chicago: John R. Stanton, 1917.

- Lloyd, John, and John Mitchinson. The Book of General Ignorance. London: Faber & Faber, 2006. ISBN 9780307394910.

- McMurtry, Larry. Sacagawea's Nickname: Essays on the American West. New York: New York Review of Books, 2001 ISBN 9780940322929.

- Schulte, Melvin. Buffalo Bill as Reported in Newspapers. Retrieved September 8, 2007.

- Warren, Louis S. Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody and the Wild West Show. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. ISBN 0-375-41216-6.

External links

All links retrieved May 8, 2023.

- The Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave

- Find-A-Grave profile for Buffalo Bill

- The life of Hon. William F. Cody, known as Buffalo Bill, the famous hunter, scout and guide. An autobiography. (1879); Digitized page images & text from the Library of Congress.

- Free mp3 files of the Autobiography of Buffalo Bill

- PBS piece on Buffalo Bill Cody

- Database and Cover Gallery of Buffalo Bills comic book appearances

- Buffalo Bill Cody Homestead in Scott County, Iowa.

- House of Deception article on Buffalo Bill's handwriting & signature.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.