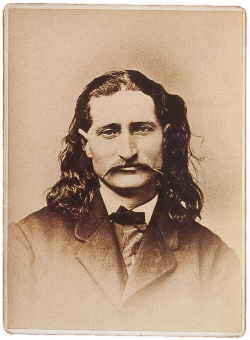

Wild Bill Hickok

| Wild Bill Hickok | |

James Butler Hickok

| |

| Born | May 27, 1837 Troy Grove, Illinois, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Died | August 2, 1876 (aged 39) Deadwood, Dakota Territory, U.S. |

| Occupation | Abolitionist, facilitator of The Underground Railroad, Lawman, Gunfighter, Gambler |

James Butler Hickok (May 27, 1837 ‚Äď August 2, 1876), better known as Wild Bill Hickok, was a legendary figure in the American Old West. His skills as a gunfighter and scout, along with his reputation as a lawman, provided the basis for his fame, although some of his exploits are fictionalized. His moniker of Wild Bill has inspired similar nicknames for men named William (even though that was not Hickok's name) who were known for their daring in various fields.

Hickok came to the West as a stage coach driver, then became a lawman in the frontier territories of Kansas and Nebraska. He fought in the Union Army during the American Civil War, and gained publicity after the war as a scout, marksman, and professional gambler. Between his law enforcement duties and gambling, which easily overlapped, Hickok was involved in several notable shootouts, and was ultimately killed while playing poker in a South Dakota saloon.

Life and career

Early life

James Butler Hickok was born in Homer (now Troy Grove), Illinois on May 27, 1837.[1] His parents were William Alonzo Hickok and Polly Butler.[2] While he was growing up, his father's farm was one of the stops on the Underground Railroad, and he learned his shooting skills protecting the farm with his father from anti-abolitionists. Hickok was a good shot from a very young age. Unknown to most, he was one of the earliest champions of equal rights for blacks during the latter days of slavery.

In 1855, he left his father's farm to become a stage coach driver on the Santa Fe and Oregon Trails. An early record refers to him as "Duck Bill" (perhaps in reference to a protruding upper lip he hid beneath a mustache), but his gunfighting skills changed his nickname to "Wild Bill." His killing of a bear with a bowie knife during a turn as a stage driver cemented a growing reputation as a genuinely tough man who feared nothing, and who was feared for more than carrying a fast gun.[3]

Constable

The Kansas-Nebraska Act opened up territory in Kansas to settlement and offered Hickok the opportunity to go West that he had so longed for.[1] In 1857, Hickok claimed a 160 acre (65 ha) tract of land in Johnson County, Kansas (in what is now the city of Lenexa) where he became the first constable of Monticello Township, Kansas. It is here that he earned the nickname William, or Bill, for reasons that historians have yet to uncover.[1] In 1861, he became a town constable in Nebraska. He was involved in a deadly shoot-out with the McCanles gang at Rock Creek Station, an event still under much debate. On several other occasions, Hickok confronted and killed several men while fighting alone.

Hickok invented the practice of "posting" men out of town. He would put a list on what was called the "dead man's tree" (so called because men had been lynched on it) while constable of Monticello Township. Hickok proclaimed he would shoot them on sight the following day. Few stayed around to find out if he was serious.

Civil War and scouting

When the Civil War began, Hickok joined the Union forces and served in the west, mostly in Kansas and Missouri. He earned a reputation as a skilled scout. After the war, Hickok became a scout for the U. S. Army and later was a professional gambler. He served for a time as a United States Marshal. In 1867, his fame increased from an interview by Henry Morton Stanley. Hickok's killing of Whistler the Peacemaker with a long-range rifle had influence in preventing the Sioux from uniting to resist the settler incursions into the Black Hills. That rifle shot helped cement Hickok's legend as a master of weapons.

During the American Civil War "Buffalo Bill Cody" served as a scout with Robert Denbow, David L. Payne, and Hickok. The men formed a friendship that would last decades. After the war the four men, Payne, Cody, Hickok, and Denbow engaged in buffalo hunting. When Payne moved to Wichita, Kansas in 1870, Denbow joined him there while Hickok served as sheriff of Hays, Kansas. Hickok was rumored to have appeared in a stage play put on in 1873 by Bill Cody entitled "Scouts of the Plains." When Bill Cody started the Buffalo Bill Wild West shows, Denbow traveled with Cody all over Iowa with the Buffalo Bill shows.

Lawman and gunfighter

On July 21, 1865, in the town square of Springfield, Missouri, Hickok killed Davis Tutt, Jr. in a "quick draw" duel. Fiction later typified this kind of gunfight, but Hickok's is in fact the only one on record that fits the portrayal.[4] The incident was precipitated by a dispute over a gambling debt incurred at a local saloon.

Hickok was working as sheriff and city marshal of Hays, Kansas when, on July 17, 1870, he was involved in a gunfight with disorderly soldiers of the 7th US Cavalry, wounding one and mortally wounding another. In 1871, Hickok became marshal of Abilene, Kansas, taking over for former marshal Thomas J. Smith.[5] Hickok's encounter in Abilene with outlaw John Wesley Hardin resulted in the latter fleeing the town after Hickok managed to disarm him.

While working in Abilene, Hickok and Phil Coe, a saloon owner, had an ongoing dispute that later resulted in a shootout. Coe had been the business partner of known gunman Ben Thompson, with whom he co-owned the Bulls Head Saloon. On October 5, 1871, Hickok was standing off a crowd during a street brawl, during which time Coe fired two shots at Hickok. Hickok returned fire and killed Coe. Hickok, whose eyesight was poor by that time in his life from early stages of glaucoma, caught the glimpse of movement of someone running toward him. He quickly fired one shot in reaction, accidentally shooting and killing Abilene Special Deputy Marshal Mike Williams who was coming to his aid, an event that affected him for the remainder of his life.[5]

Hickok's retort to Coe, who supposedly stated he could "kill a crow on the wing," is one of the West's most famous sayings (though possibly apocryphal): "Did the crow have a pistol? Was he shooting back? I will be."

Death

On August 2, 1876, while playing poker at Nuttal & Mann's Saloon No. 10 in Deadwood, in the Black Hills, Dakota Territory, Hickok could not find an empty seat in the corner, where he always sat in order to protect himself against sneak attacks from behind, and instead sat with his back to one door and facing another. His paranoia was prescient: he was shot in the back of the head with a .45-caliber revolver by Jack McCall.[6] Legend has it that Hickok, playing poker when he was shot, was holding a pair of aces and a pair of eights. The fifth card was either unknown, or some say that it had not yet been dealt. This famous hand of cards is known as the "Dead Man's Hand."

The motive for the killing is still debated. McCall may have been paid for the deed, or it may have been the result of a recent dispute between the two. Most likely McCall became enraged over what he perceived as a condescending offer from Hickok to let him have enough money for breakfast after he had lost all his money playing poker the previous day. McCall claimed at the resulting two-hour trial, by a miners jury, an ad hoc local group of assembled miners and businessmen, that he was avenging Hickok's earlier slaying of his brother which was later found untrue. McCall was acquitted of the murder, resulting in the Black Hills Pioneer editorializing:

- "Should it ever be our misfortune to kill a man ... we would simply ask that our trial may take place in some of the mining camps of these hills"

McCall was subsequently rearrested after bragging about his deed, and a new trial was held. The authorities did not consider this to be double jeopardy because at the time Deadwood was not recognized by the U.S. as a legitimately incorporated town because it was in Indian Country and the jury was irregular. The new trial was held in Yankton, capital of the territory. Hickok's brother, Lorenzo Butler Hickok, traveled from Illinois to attend the retrial. This time McCall was found guilty and hanged on March 1, 1877. After his execution it was determined that McCall had never had a brother.[6]

Charlie Utter, Hickok's friend and companion, claimed Hickok's body and placed a notice in the local newspaper, the Black Hills Pioneer, which read:

"Died in Deadwood, Black Hills, August 2, 1876, from the effects of a pistol shot, J. B. Hickok (Wild Bill) formerly of Cheyenne, Wyoming. Funeral services will be held at Charlie Utter's Camp, on Thursday afternoon, August 3, 1876, at 3 o'clock P. M. All are respectfully invited to attend."

Almost the entire town attended the funeral, and Utter had Hickok buried with a wooden grave marker reading:

"Wild Bill, J. B. Hickok killed by the assassin Jack McCall in Deadwood, Black Hills, August 2d, 1876. Pard, we will meet again in the happy hunting ground to part no more. Good bye, Colorado Charlie, C. H. Utter."

In 1879, at the urging of Calamity Jane, Utter had Hickok reinterred in a ten-foot (3 m) square plot at the Mount Moriah Cemetery, surrounded by a cast-iron fence with a U.S. flag flying nearby. A monument has since been built there. In accordance with her dying wish, Calamity Jane was buried next to him.

Shortly before Hickok's death, he wrote a letter to his new wife, Agnes Lake Thatcher, which reads in part: "Agnes Darling, if such should be we never meet again, while firing my last shot, I will gently breathe the name of my wife‚ÄĒAgnes‚ÄĒand with wishes even for my enemies I will make the plunge and try to swim to the other shore" and "My dearly beloved if I am to die today and never see the sweet face of you I want you to know that I am no great man and am lucky to have such a woman as you." Hickok had a passion for women and took on many live-in lovers over the course of his lifetime, though he had finally settled down with Agnes a mere five months before his death. The couple were wed in Cheyenne.[7]

Hickok's sisters mourned him dearly, but his mother took his death especially hard. She would remain in a state of deep grief until her death two years later.[6]

Buffalo Bill

Some accounts report that Hickok took part in Buffalo Bill's Wild West. However, that production was not in existence prior to 1882, well after Hickok's death. Nonetheless, Hickok was reported by some to have appeared with Buffalo Bill in 1873 in a stage play titled "Scouts of the plains."[8]

In popular culture

"Dime novel" fame

It is difficult to separate the truth from fiction about Hickok, the first "dime novel" hero of the western era, in many ways one of the first comic book heroes, keeping company with another who achieved part of his fame in such a way, frontiersman Davey Crockett. In the dimestore novels, exploits of Hickok were presented in heroic form, making him seem larger than life. In truth, most of the stories were greatly exaggerated or fabricated.

Hickok told the writers that he had killed over 100 men. This number is doubtful, and it is more likely that his total killings were about 20 or a few more. Hickok was a fearless and deadly fighting man, versatile with a rifle, revolver, or knife. His story of fighting a grizzly bear, which he claims mistook him for food because of his greasy buckskins, personified a man who feared nothing. According to Wild Bill, he killed the bear with a Bowie knife after emptying his pistols into the bear. That story is also thought to be an exaggeration.

Television

- Portrayed by Guy Madison in the 1951-1958 series (The Adventures of) Wild Bill Hickok.

- the same cast also appeared in the Mutual Broadcasting radio show "The Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok" from April 1, 1951 through December 31, 1954, a total of 271 half hour radio programs.

- Played by Lloyd Bridges in a 1964 episode of the anthology The Great Adventure.

- Portrayed by Josh Brolin in the 1989-1992 series The Young Riders.[9]

- Featured in the 1995 series Legend, episode 1.06 "The Life, Death and Life of Wild Bill Hickok." The episode portrays his death factually but then goes on to show that he faked his own death (wearing a sort of bullet-proof vest), so that he could retire peacefully.

- Dramatized in the HBO series Deadwood,[10] in which he is portrayed by Keith Carradine.

- In the 1995 made-for-TV film Buffalo Girls[11] based on the best-selling novel of the same name by Larry McMurtry, he was played by actor Sam Elliott with Anjelica Huston as Calamity Jane. The film touched briefly on Hickok's days as an Army scout and gambler, and his death was portrayed factually. However, the film (as does the book on which it is based) gives credence to the legend that Calamity Jane had a daughter by him, born posthumously.

Movies

- Played by Gary Cooper in the 1936 film The Plainsman, featuring Jean Arthur as Calamity Jane and directed by Cecil B. DeMille.[12]

- Played by Howard Keel in the 1953 film Calamity Jane.[13]

- Portrayed by Jeff Corey in the 1970 Dustin Hoffman movie Little Big Man.[14]

- Portrayed by Charles Bronson in the 1977 movie The White Buffalo.

- Portrayed by Jeff Bridges in the 1995 movie Wild Bill.[15].

- Played by Sam Shepard in the 1999 movie Purgatory, a made-for-TV movie on TNT.

Novels

- The Memoirs of Wild Bill Hickok. Richard Matheson, ISBN 0515117803

- Deadwood. Pete Dexter - 1986

- And Not to Yield. Randy Lee Eickoff

- "A Breed Apart." Max Evans in Hi Lo to Hollywood: A Max Evans Reader. 1998

- The White Buffalo. Richard Sale

Songs

- Wild Bill Hickok is featured with Calamity Jane in the song "Deadwood Mountain" by the country duo "Big & Rich."

- Wild Bill is sung about in Bluegrass band Blue Highway's song "Wild Bill" from the album Marbletown.

Trivia

- Hickok's death chair[16] is now in a glass case above the saloon entrance, though the saloon was moved after the original Nuttall & Mann's #10 saloon burned down; the original site is down the street to the north, about a block away.

- He preferred his own cap and ball Colt 1851 .36 Navy Model handguns. They had ivory handles and were engraved with his name, "J.B. Hickok." He acquired them shortly after or at the very close of the Civil War, for which he was a scout and spy. They had no triggers; Wild Bill would pull them up holding their hammers, and release to fire, giving him a slight speed advantage.

- He wore his revolvers in reverse at his hips, sometimes in a red sash, and drew them from the inside, from the right hip with left hand and the left hip with right hand, claiming it was faster that way.

- Hickok was inducted into the Poker Hall of Fame in 1979.

- He also would tell tourists various exaggerated exploits of his, usually leaving himself unarmed with no manner of escape, and then stop talking. When someone would inevitably ask what he did then, he claimed "I was surrounded. What could I do? They killed me."

Legacy

After his death, Hickok was forever enshrined in American popular culture as a folk legend. His calm demeanor under pressure facilitated his fine marksmanship. He would become a major character in Westerns after the advent of film (and was even considered the most popular figure until the late 1930s). His exploits may have been exaggerated, but he is still a noteworthy individual. Hickok was a man that did what he felt was right. At times the pursuit of justice even prompted him to place himself in harm's way. He was the type of man that inspired a loyal following and garnered praise. The manner in which Hickok died helped to further his legend and added to his allure. He would be remembered as a man who was never taken down in a fair fight, no matter how high the odds against him might be stacked.[6]

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Joseph G. Rosa, "Living Legend, Dead Hero, Frontier Icon," in With Bullets & Badges: Lawmen & Outlaws in the Old West, eds. Richard W. Etulain and Glenda Riley (Golden: Fulcrum Publishing, 1999), 32-33.

- ‚ÜĎ James Butler Hickok Wild Bill Geneanet. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ‚ÜĎ Jerome C. Krause, James Butler (Wild Bill) Hickok The Jacana Great Lives Site. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ‚ÜĎ Shoot Out with "Wild Bill" Hickok, 1869. EyeWitness to History, 2005. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ‚ÜĎ 5.0 5.1 Wild Bill Hickok. HistoryNet. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ‚ÜĎ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Rosa, "Living Legend," 52.

- ‚ÜĎ Rosa, "Living Legend," 39.

- ‚ÜĎ A Brief History of William F. ‚ÄúBuffalo Bill‚ÄĚ Cody. The Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ‚ÜĎ Internet Movie Database, The Young Riders. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ‚ÜĎ Internet Movie Database, Deadwood. Deadwood Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ‚ÜĎ Internet Movie Database, Buffalo Girls. Buffalo Girls. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ‚ÜĎ Internet Movie Database, The Plainsman, The Plainsman. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ‚ÜĎ Internet Movie Database, Calamity Jane, Calamity Jane. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ‚ÜĎ Internet Movie Database, Little Big Man, Little Big Man Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ‚ÜĎ Internet Movie Database, Wild Bill, Wild Bill. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ‚ÜĎ Wild Bill's Death Chair, Death Chair of Wild Bill Hickok RoadsideAmerica. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Matheson, Richard. The Memoirs of Wild Bill Hickok. New York: Jove, 1996. ISBN 0515117803

- Rosa, Joseph G. "Living Legend, Dead Hero, Frontier Icon." In With Bullets & Badges: Lawmen & Outlaws in the Old West, edited by Richard W. Etulain and Glenda Riley, 27-52. Golden: Fulcrum Publishing, 1999. ISBN 978-1555914332

- Rosa, Joseph G. They Called Him Wild Bill. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1979. ISBN 0806115386

- Rosa, Joseph G. The West of Wild Bill Hickok. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994. ISBN 0806126809

- Rosa, Joseph G. Wild Bill Hickok: The Man and His Myth. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1996. ISBN 0700607730

- Rosa, Joseph G. Wild Bill Hickok Gunfighter: An Account of Hickok's Gunfights. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003. ISBN 0806135352

- Turner, Thadd M. Wild Bill Hickok: Deadwood City - End of Trail. Boca Raton: Universal Publishers, 2001. ISBN 1581126891

- Wilstach, Frank Jenners. Wild Bill Hickok: The Prince of Pistoleers. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1926. ASIN B00085PJ58

External links

All links retrieved May 4, 2023.

- Wild Bill Hickok & the Deadman's Hand Legends of America.

- Wild Bill Hickok: Pistoleer, Peace Officer and Folk Hero. Originally published in Wild West magazine.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.