Badlands National Park

| Badlands National Park | |

|---|---|

| IUCN Category II (National Park) | |

| | |

| Location: | South Dakota, USA |

| Nearest city: | Rapid City, South Dakota |

| Area: | 242,755.94 acres (982.40 km²), 232,822.24 acres (942.20 km²) federal |

| Established: | January 29, 1939 National Monument November 10, 1978 National Park |

| Visitation: | 928,010 (in 2005) |

| Governing body: | National Park Service |

Badlands National Park, in southwest South Dakota, United States preserves 242,756 acres (982 km²) of sharply eroded buttes, pinnacles and spires blended with the largest protected mixed grass prairie in the United States. Efforts to preserve this uniquely scenic geologic setting east of the Black Hills led to the establishment of Badlands National Monument in 1929; it became a national park in 1978. This park is marked by rugged terrain and rock formations that resemble landscapes from another world.

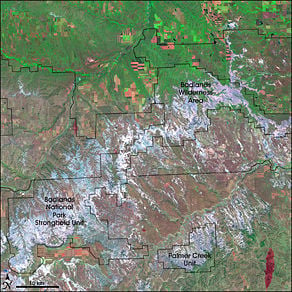

The Badlands Wilderness, designated by Congress in 1976, is located entirely within Badlands National Park and is managed by the National Park Service. Badlands Wilderness includes 64,250 acres (260 km²) of the most pristine sections of the national park. Within this wilderness, buffalo still roam free and visitors can also find bighorn sheep, coyotes, mule deer, as well as the most endangered land mammal in North America, the black-footed ferret, which was re-introduced to the Wilderness area.

The Stronghold Unit of the park, which is located within the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, is co-managed with the Oglala Sioux tribe. This is the site of the Stronghold Table where in the 1890s the Sioux Indians performed their Ghost Dances.

Strikingly beautiful and mystical, the Badlands take their name from both the Lakota Sioux tribe as well as French fur trappers. The Lakota referred to the area as Mako Sica while the French called it les mauvaises terres a traverser. Both mean bad lands, or a difficult place cross.

Geology

The Badlands are an awe-inspiring, ever-changing masterpiece formed by wind and water. The plateaus of soft sediments and volcanic ash reveal colorful bands of flat-lying strata.

Approximately 65 - 75 million years ago, a shallow sea teeming with life, covered what is now the Great Plains region. At the bottom of that sea in the Badlands of today is an incredibly rich source of fossils that appear in a layer of a grayish-black, 2,000 foot thick, sedimentary rock called Pierre (pronounced âpeerâ) shale.

About 60 million years ago, during the formation of the Rocky Mountains, large number of streams carried eroded soil, rock, and other materials eastward from the range. These materials were deposited on the vast lowlands which are today known as the Great Plains. Dense vegetation grew in these lowlands, then fell into swamps, and was later buried by new layers of sediment. Millions of years later, this plant material turned into lignite coal. Some of the plant life became petrified, and large amounts of exposed petrified wood can be found here. While sediments continued to be deposited, more streams cut down through the soft rock layers, carving the variety of mesas, buttes, rock formations, pinnacles, spires, and valleys that are the features of today's Badlands.

During the Oligocene epoch 40 to 25 million years ago, the area supported many now-extinct animals that perished in floods and were quickly buried in river sediments. The conditions for preservation were excellent and the Badlands National Park now contains the world's richest Eocene/Oligocene Epoch fossil beds. Scientists, drawn by the fossilized remains of miniature camels and horses, saber-toothed cats, and huge rhinoceros-like beasts known as titanotheres, have discovered millions of years of geologic history buried in this unique region. With erosion continuing to this day, long-buried fossils are still being revealed.

Geography

Rock formations take on the shapes of domes, twisted canyons, and slanted walls, often striped in different colors. The formations contrast sharply with the rolling hills and prairies in which they stand. In addition to the rock formations, the park contains the largest protected mixed-grass prairie in the United States.

Flora and fauna

While the badlands terrain may appear to be barren, there is a great variety of wildlife and plant life here. With an annual precipitation of barely 16 inches, the more than 60 types of grasses and dozens of flowering plants still seem to thrive. Grasses do well with three-fourths of the plant below ground. The brilliant colors of the wildflowers add to the palette of grays, browns, reds, and greens of the land. Settlers, through deliberate or accidental means, brought dozens of non-native species of plants. The park is actively working to remove the non-native plants and restore the prairie to its original condition.

The wildlife includes more than two hundred species of birds such as owls, doves, swallows, hawks, shorebirds, and waterfowl. The most commonly seen mammals are the mule deer. Seen less often are white-tailed deer, pronghorn, bighorn sheep, and bison. Other mammals in the park include prairie dogs, bats, rabbits, and coyotes. Reptiles and amphibians include frogs, toads, and snakes.

The black-footed ferret, the most endangered land mammal in North America, was reintroduced to the Sage Creek Wilderness area of the park. Thought to be extinct in the 1970s, a small colony was found on a ranch in Wyoming. From just 18 ferrets, a captive breeding program was developed and Badlands National Park was selected as an area for reintroduction. Park staff are encouraged by the presence of wild-born kits, which are now producing young of their own.

Climate

Winter begins in November, although blizzards in late October may occur. High temperatures are around 40° F (4.4° C) with lows below 0° F (-18° C) with high winds creating a much lower wind chill. Throughout most of the winter, snow is likely and blizzards are possible. March temperatures may fluctuate dramatically within a few hours. Blizzards are still possible, and so is 60° F (15.5° C) weather.

Spring begins in April. With snow melting and April rains, the park is very wet. The unpaved roads can be difficult or impossible to pass and trails may be slippery. Temperatures at night are typically below freezing. The park receives most of its rain between April and June. Showers may be brief or last for days. It begins to get quite warm by the end of June.

July is hot and dry. Daytime temperatures can surpass 90° F (32° C). August is the hottest month when temperatures can break 100° F (38° C). Evenings are about 75° F (24° C). In September the temperatures begin to cool off in the second half of the month, making it a prime time to visit the park. October is much cooler although a few days may break 80° F (27° C).

Human history

American Indians

For eleven thousand years, Native Americans have used this area for their hunting grounds. Long before the Lakota were the little-studied paleo-Indians, followed by the Arikara people. Their descendants live today in North Dakota as a part of the Three Affiliated Tribes. Archaeological records combined with oral traditions indicate that these people camped in secluded valleys where fresh water and game were available year-round. Eroding out of the stream banks today are the rocks and charcoal of their campfires, as well as the arrowheads and tools they used to hunt bison, rabbits, and other game. From the top of the Badlands Wall, they could scan the area for enemies and wandering herds. If hunting was good, they might stay through the winter, before retracing their way to their villages along the Missouri River. By one hundred and fifty years ago, the Great Sioux Nation consisting of seven bands including the Oglala Lakota, had displaced the other tribes from the northern prairie.

The next great change came toward the end of the nineteenth century as homesteaders moved into South Dakota. The U.S. government stripped Native Americans of much of their territory and restricted them to living on reservations. In the fall and early winter of 1890, thousands of Native American followers, including many Oglala Sioux, became followers of the Indian prophet Wovoca. His vision called for the native people to dance the Ghost Dance and wear Ghost Shirts, which would be impervious to bullets. Wovoca had predicted that the white man would vanish and their hunting grounds would be restored. One of the last known Ghost Dances was conducted on Stronghold Table in the South Unit of Badlands National Park. As winter closed in, the ghost dancers returned to Pine Ridge Agency. The climax of the struggle came in late December 1890. Headed south from the Cheyenne River, a band of Minneconjou Sioux Indians crossed a pass in the Badlands Wall. Pursued by units of the U.S. Army, they were seeking refuge in the Pine Ridge Reservation. The band, led by Chief Big Foot, was finally overtaken by the soldiers near Wounded Knee Creek in the Reservation and ordered to camp there overnight. The troops attempted to disarm Big Foot's band the next morning. Gunfire erupted. Before it was over, nearly 200 Indians and 30 soldiers lay dead. The Wounded Knee massacre was the last major clash between American Indians and the U.S. military until the American Indian Freedom actions of the 1970s, most notably again, at Wounded Knee, South Dakota.

Wounded Knee is not within the boundaries of Badlands National Park. It is located approximately 45 miles south of the park on Pine Ridge Reservation. The U.S. government and the Oglala Lakota Nation have agreed that this is a story to be told by the Oglala of Pine Ridge and Minneconjou of Standing Rock Reservation. The interpretation of the site and its tragic events are held as the primary responsibility of these survivors.

Fossil hunters

The history of the White River Badlands as a significant paleontological resource goes back to the traditional Native American knowledge of the area. The Lakota found large fossilized bones, fossilized seashells, and turtle shells. They correctly assumed that the area had once been under water, and that the bones belonged to creatures that no longer existed. Paleontological interest in this area began in the 1840s. Trappers and traders regularly traveled the 300 miles from Fort Pierre to Fort Laramie along a path that skirted the edge of what is now Badlands National Park. Fossils were occasionally collected, and in 1843 a fossilized jaw fragment collected by Alexander Culbertson of the American Fur Company found its way to a physician in St. Louis by the name of Dr. Hiram A. Prout.

In 1846, Prout published a paper about the jaw in the American Journal of Science in which he stated that it had come from a creature he called a Paleotherium. Shortly after the publication, the White River Badlands became popular fossil hunting grounds and, within a couple of decades, numerous new fossil species had been discovered in the White River Badlands. In 1849, Dr. Joseph Leidy published a paper on an Oligocene camel and renamed Prout's Paleotherium, Titanotherium prouti. By 1854, when he published a series of papers about North American fossils, 84 distinct species had been discovered in North America â77 of which were found in the White River Badlands. In 1870 a Yale professor, O. C. Marsh, visited the region and developed more refined methods of extracting and reassembling fossils into nearly complete skeletons. From 1899 until today, the South Dakota School of Mines has sent people almost every year to the White River Badlands and remains one of the most active research institutions working there. Throughout the late 1800s and continuing today, scientists and institutions from all over the world have benefited from the fossil resources of the White River Badlands, which have developed an international reputation as a fossil-rich area. They contain the richest deposits of Oligocene mammals known, providing a brief glimpse of life in this area 33 million years ago. Comparisons between the fossils here and fossils of similar age around the world have helped paint a picture of life on earth millions of years ago.

Homesteaders

Aspects of American homesteading began before the end of the American Civil War; however, homesteading didn't really impact the Badlands until well into the 20th century. Many hopeful farmers traveled to South Dakota from Europe or the East Coast to try to eke out a living in this hard place. The standard size for a homestead was 160 acres. This proved far too small to support a family in a semi-arid, wind-swept environment. In the western Dakotas, the size of a homestead was increased to 640 acres. Cattle grazed and crops such as winter wheat and hay were cut annually. However, the Great Dust Bowl events of the 1930s combined with waves of grasshoppers proved too much for most of the hardy souls of the Badlands. Houses built of sod blocks and heated by buffalo chips were soon abandoned. Those who remained are still here today â ranching and raising wheat.

Gunnery range

The Stronghold District of Badlands National Park offers more than scenic badlands with spectacular views. Co-managed by the National Park Service and the Oglala Sioux Tribe, this 133,300-acre area is also steeped in history. Deep draws, high tables, and rolling prairie hold the stories of the earliest Plains hunters, the paleo-Indians, as well as the present day Lakota Nation. Homesteaders and fossil hunters have also made their mark on the land. There is a more recent role this remote, sparsely populated area has played in U.S. history: World War II and the Badlands gunnery range.

As a part of the war effort, the U.S. Air Force (USAF) took possession of 341,726 acres of land on the Pine Ridge Reservation, home of the Oglala Sioux people, for a gunnery range. Included in this range was 337 acres from what was then Badlands National Monument. This land was used extensively from 1942 through 1945 as air-to-air and air-to-ground gunnery ranges. Precision and demolition bombing exercises were also quite common. After the war, the South Dakota National Guard used portions of the bombing range as an artillery range. Pilots in practice, operating out of Ellsworth Air Force Base near Rapid City, found it a challenge to determine the exact boundaries of the range. Fortunately, there were no civilian casualties. However, at least a dozen members of flight crews lost their lives in plane crashes. In 1968, the USAF declared most of the range excess property. Twenty-five hundred acres are retained by the USAF, but are no longer used.

Activities

One way to enjoy the area is to drive the Highway 240 Loop Road, a one-hour drive. There are also several informative Ranger Programs to attend, which last 20 minutes to an hour. Stopping in at the Visitor Center to watch the park video and see the various exhibits is highly recommended.

Day hikes

- Medicine Root Trail. Moderate 4 miles (2.5 km) loop. Here the mixed-grass prairie combines with long-distance views of the Badlands. Be on the lookout for prickly pear cacti.

- Castle Trail. Moderate 10 miles (16 km) round-trip. This is the longest trail in the park. The trail is mostly level and winds through some formations. The Medicine Root Trail makes a loop within the Castle Trail from any connecting trailhead.

- Cliff Shelf Nature Trail. Moderate 0.5 miles (0.8 km) loop. This trail provides spectacular views of the White River Valley. It includes some boardwalk and stairs and climbs approximately 200 feet (61 meters). It passes through some heavy vegetation, a rare site in this stark landscape.

- Door Trail. Easy 0.75 miles (1.2 km) round-trip. This trail is accessible. It focuses on geology. The trail goes through a break in the Badlands Wall called "The Door." The Badland Wall stretches east to west for nearly 60 miles. The first 150 yards (137 meters) of the trail is boardwalk.

- Fossil Exhibit Trail. Easy 0.25 miles (0.4 km) loop. This trail is fully accessible. The trail includes exhibits of now extinct creatures that once roamed the area. Presentations by park naturalists are offered during the summer months.

- Notch Trail. Moderate to strenuous 1.5 miles (2.4 km) round-trip. This trail leads to a small opening atop the Badland Wall and is not recommended for those with a fear of heights. This trail provides a wonderful view of the White River Valley and Pine Ridge Reservation. The trail, however, can be very dangerous just after heavy rains.

- Saddle Pass Trail. Strenuous 0.2 miles (0.4 km) and very steep, it connects Castle Trail and Medicine Root Loop to the Badlands Loop Road. The trail is impassable after rain.

- Window Trail. Easy 0.25 miles (0.4 km) round-trip. This short boardwalk trail is accessible to athletic wheelchair users or with assistance. This trail goes to a natural "window" in the Badlands Wall.

Camping and backpacking

There are two campgrounds within the Badlands National Park:

- Cedar Pass Campground

- Sage Creek Campground

Backpackers may camp anywhere in the park that is at least one half-mile from any trail or road. The 64,250-acre Sage Creek Wilderness area is ideal for backpacking. It is recommended backpackers check in at the Ben Reifel Visitor Center for maps, assistance, and to inform the Park Rangers to your presence.

Sources and Futher reading

Online sources

- National Park Service. Badlands National Park, Retrieved July 22, 2007.

- Wikitravel. Badlands National Park, Retrieved July 22, 2007.

Print sources

- Cerney, Janice Brozik. 2004. Badlands National Park. (Images of America.) Charleston, SC: Arcadia. ISBN 0738532266

- The National Parks: Index 2001â2003. Washington: U.S. Department of the Interior.

- Retallack, Greg J. 1983. Late Eocene and Oligocene paleosols from Badlands National Park, South Dakota. Boulder, Colo: Geological Society of America. ISBN 0813721938

- Temple, Teri, and Bob Temple. 2007. Welcome to Badlands National Park. Visitor guides. Chanhassen, Minn: Child's World. ISBN 1592966934

- United States. 2006. Final general management plan, environmental impact statement: Badlands National Park, North Unit. [Washington, DC]: National Park Service, U.S. Dept. of the Interior.

- Wade, Linda R. 1991. Badlands: beauty carved from nature. Vero Beach, Fla: Rourke Enterprises. ISBN 0865924716

External links

All links retrieved August 26, 2023.

- National Park Services. Badlands.

- Maps and aerial photos

- WikiSatellite view at - WikiMapia

- Satellite image from Google Maps, Windows Live Local

- Street map from Google Maps, or Yahoo! Maps, or Windows Live Local

- Topographic map from TopoZone

| National parks of the United States | |

|---|---|

| Acadia ⢠American Samoa ⢠Arches ⢠Badlands ⢠Big Bend ⢠Biscayne ⢠Black Canyon of the Gunnison ⢠Bryce Canyon ⢠Canyonlands ⢠Capitol Reef ⢠Carlsbad Caverns ⢠Channel Islands ⢠Congaree ⢠Crater Lake ⢠Cuyahoga Valley ⢠Death Valley ⢠Denali ⢠Dry Tortugas ⢠Everglades ⢠Gates of the Arctic ⢠Glacier ⢠Glacier Bay ⢠Grand Canyon ⢠Grand Teton ⢠Great Basin ⢠Great Sand Dunes ⢠Great Smoky Mountains ⢠Guadalupe Mountains ⢠Haleakala ⢠Hawaii Volcanoes ⢠Hot Springs ⢠Isle Royale ⢠Joshua Tree ⢠Katmai ⢠Kenai Fjords ⢠Kings Canyon ⢠Kobuk Valley ⢠Lake Clark ⢠Lassen Volcanic ⢠Mammoth Cave ⢠Mesa Verde ⢠Mount Rainier ⢠North Cascades ⢠Olympic ⢠Petrified Forest ⢠Redwood ⢠Rocky Mountain ⢠Saguaro ⢠Sequoia ⢠Shenandoah ⢠Theodore Roosevelt ⢠Virgin Islands ⢠Voyageurs ⢠Wind Cave ⢠Wrangell-St. Elias ⢠Yellowstone ⢠Yosemite ⢠Zion List by: date established, state |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.